Against the backdrop of broad and interrelated changes in military systems, weapons, doctrine, tactics and strategy sweeping across the European continent in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Conscription in Finland in the interwar period represents an interesting borderland both in place and in time. Almost 150 years earlier, the American revolution had introduced the modern notion of a “people in arms” (largely based on the Swiss militia) and displayed the military potential of civic enthusiasm against the well-drilled, machine-like obedience of professional soldiers who were either fighting for money or enlisted by force. In Europe, the Republic of Revolutionary France introduced universal forced conscription for males and amazed Europe with the striking power of it’s mass armies of “citizen-soldiers”. In spite of its radical and democratic associations, authoritarian monarchies such as Prussia, Austria and Russia were one after the other forced to introduce conscription on one form or another in a kind of chain reaction stretching over the course of the nineteenth century.

Conscription not only enabled the raising of ever larger armies. The new “citizen armies” were marked by a higher degree of motivation than in previous centuries, largely because they were accompanied by strong feelings of patriotism and of civic participation, of free men fighting for their own republic or nation. Moreover, universal conscription allowed for the mobilisation of entire societies for increasingly violent “total” wars, as the fact that almost every family had a member fighting in the army meant that each thus became directly engaged in the war effort. Universal conscription linked together soldiering, nationalism and citizenship into varying yet always very powerful ideological configurations.

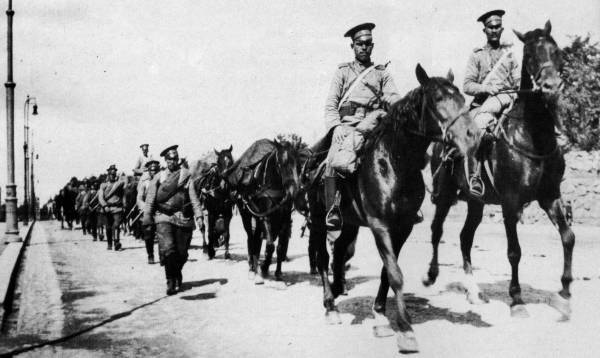

In the nineteenth century, in fact up until the end of the First World War, Finland had been an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire, essentially a pacified buffer zone between Sweden and Russia protecting St Petersburg from the northwest. During this period, Finland’s defence was mostly handled by Russian troops. During the two last decades of the nineteenth century, a limited form of universal conscription for male Finns was introduced as part of military reform in Russia, but only one tenth of each age cohort was actually drafted for active service. These “Finnish” troops gratified the rising nationalist sentiments among the Finnish elite, but were in effect designed to serve the Russian Empire’s strategic objectives. Conscription in Finland was actually abolished when Finnish nationalism and Russian imperial policies came into conflict around the turn of the century.

Russian troops in Helsinki 1914. (Photo: Ivan Timirjasev, Helsinki City Museum)

When independence was declared in December 1917, there had been no conscription and no compulsory military training in Finland for almost two decades. However, as we have seen, domestic social tensions resulted in a short but bitterly fought civil war in 1918. The victorious non-socialists had to face the military presence of a Bolshevik power consolidating on their Eastern border. Suddenly, trained soldiers were desperately needed to protect Finnish society. Finnish men had to be made into soldiers. The situation that resulted could be described as a fast-forward into European military modernity. A new institutional framework of universal conscription in Finland and compulsory military training was introduced, with influences from different countries and different military doctrines clashing with each other in an interwar Finland.

Foreign military doctrines were imported by Finnish officers who had served or studied in Russia, Germany, and post-WW1, in other countries. Democratic-republican ideas of “arming the people” rubbed shoulders with authoritarian military traditions from monarchic empires. A largely rural-agrarian class of young men, used to hard physical work and from a society with no recent tradition of military service (and not accustomed to the mental and physical discipline of a modern educational or military system) were suddenly and compulsorily introduced to a rigid military system and hierarchy. In addition, there were major tensions between socialists and non-socialists who disagreed on what kind of Finnish nation they wanted to create. Patriotic euphoria over national independence collided with the post-war gloom of a nation trying to come to terms with a bitter civil war and a continent trying to recover from the shock of a world-wide industrial war that had killed millions, lead to the collapse of Empires and much of the old order – and rocked the self-assurance of European civilisation.

In the period beginning with the Civil War of 1918 and continuing over the two decades up to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Finland underwent a sudden and rapid militirisation, both materially and mentally. The military, political and social ruling elite saw the new Finnish national armed forces, consisting both of the regular army and the voluntary Suojeluskunta, as the force at the core of national liberation and the guarantor of Finland’s independence and social order against both internal and external Bolshevik threats. Universal male conscription was reintroduced in 1918, and from there on, for the first time in Finnish history, every young man declared able-bodied was not only expected to fight for his nation in wartime, but subjected for at least one year to compulsory military service in a peacetime standing army. In this, the Finnish Army aimed to train all men in military skills, without regard to social standing or class background.

The military depicted universal conscription and the conscript army as central instruments for national integration and civic education. The shared experience of military service would unite young men of all backgrounds and classes into a closely knit national community through the tough but shared experience of military service. However, the new conscription institution and its incarnation in the standing conscript army were the objects of intense suspicion and public criticism, particularly in the first decade of national independence. The criticism ranged from concerns over the undemocratic spirit in the officer corps to outrage over poor sanitary conditions in the garrisons. There was a great reluctance within civilian society, not so much against the general principle of male conscription, as against the particular forms that the military system had adopted.

The politics of conscription in Finland

The first conscripts in the new Finnish Army were called up for service less than a year after the end of the Civil War of 1918. Tens of thousands had died in the fighting, been executed or died through famine and disease in the internment camps. The call-up was thoroughly repulsive to those conscripts who sympathised with the socialist insurgents. In many cases, their fathers, uncles or brothers had been killed in combat, executed or starved to death by that very army now summoning them for military service. Even for non-socialist young men who embraced “white” patriotism entered the army with grave reasons for anxiety. The press printed reports of dismal sanitary conditions, food shortages and poor clothing in the garrisons. There was also an imminent danger that the conscripts would soon see real military action. Russia was in the turmoil of revolution and civil war. Finnish volunteer forces were engaged in fighting against Bolshevik troops in Eastern Karelia, the region north of St Petersburg and Lake Ladoga, and in Estonia. In the spring and summer of 1919, rumors abounded that Mannerheim was planning an attack on St Petersburg. Just as the threat of war in the East seemed to diminish, troops were sent to the south-western Åland islands to fend off an anticipated attempt by Sweden to occupy and annex the islands. Military service and the conscript army were a new and strange phenomena.

From public indignation to closing ranks around the army

The permanent conscription law cementing the cadre system and fixing military service to 12 months was finally passed in 1922. Yet political tension surrounding the conscript army only eased very slowly. Up until the mid-1920’s and beyond, the armed forces’ public image was dominated by power-struggles within the very heterogeneous officer corps and a series of scandals involving mismanagement and embezzlement of military equipment and funds. Even more crucial for the public images of conscripted soldiering were continued reports in the press on insanitary housing conditions, deficient medical services and abusive treatment of the conscripts by their superiors. This negative image of conscript soldiering only started changing towards the end of the 1920’s. The 1930’s were marked by a closing of ranks around the conscript army, in the midst of building international tensions.

Public images of military education in the early to mid-1920’s were often far flung from notions of the army as a ‘school for men’ where youngsters became loyal, dutiful and patriotic citizens. Rather, it was often claimed even in the non-socialist press that the mistreatment of soldiers in the armed forces harmed national defence by undermining the soldiers’ motivation and making them loath the military. This, incidentally, had been one of the key arguments against the cadre army and in favour of the militia system. The Social Democrats often brought up critique of the moral and material conditions in the armed forces when the defence budget surfaced for discussion in parliament. For example, in the budgetary debate in December 1921, MP E. Huttunen listed several cases of mismanagement within the military administration as well as a number of recent homicides and suicides within the armed forces. He complained about the widespread abuse of alcohol in spite of the prohibition law enacted in 1919, the use of prostitutes, and the spread of venereal diseases among both officers and soldiers.

He read aloud a letter from a conscript in a Helsinki unit who had tried to stay sober, but been subjected to scorn and even battering by his comrades for lacking the “spirit of comradeship”. Officers used soldiers as their personal servants, claimed Huttunen, sending them to buy smuggled liquor from bootleggers, making them collect their officers dead drunk from the officers’ mess at night, undress them and wipe up their vomits. “It is something so degrading and in addition there is always the risk of [the soldier] getting assaulted [by an officer], which often happens”, Huttunen thundered, eventually ending his oration by demanding some minor cuts in military funding.

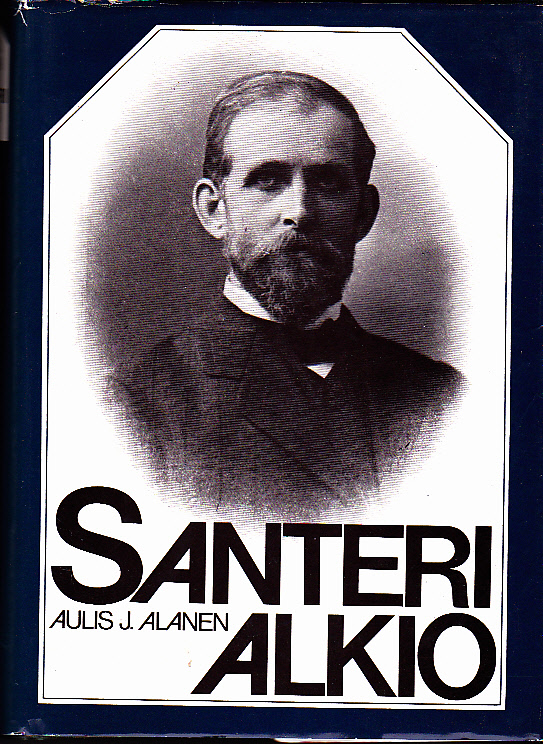

Santeri Alkio, Agrarian Party idealogue

All this could perhaps have been attributed to ingrained socialist antimilitarism, had not the agrarian ideologue Santeri Alkio stated in the next address that he agreed with Huttunen’s description of the state of affairs in the army. The inebriation in the military was commonly known, said Alkio, who blamed “customs inherited from Russia” within the officers’ corps for these evils, only to be interrupted by an interjection from the left: “They are just as much from Germany!” Alkio told parliament that many mothers and fathers who had to leave their sons in the army’s charge trembled in their hearts, wondering in what shape they would get their children back. “Many have been in tears telling me that their sons who left home morally pure have returned from military service morally fallen, having lost their faith in life and cursing the system that have made them such poor creatures”, Alkio declared “If the “Russian order” in the army was not uprooted, Finland’s defence was at peril”.

Public concerns running high

A high-water mark in the public discourse about the Finnish Army as a dangerous and degrading environment for young men was reached as late as December 9th, 1924. On that day, MPs of all political hues spent ten hours of the budget debate roundly denouncing on the army’s mistreatment of the conscripted soldiers.118 A recurrent notion in the debate, expressed across the political spectrum, was that the will to defend the nation was fundamentally threatened by the conscripts’ negative experiences of military service. MP Otto Jacobsson of the conservative Swedish People’s Party talked about the “absolutely reprehensible way in which recruit training is conducted”, the “groundless punishment drill”, “exercises through which conscripts are meaninglessly subjected to the risk of life-threatening illness”, and “punishments obviously aimed at disparaging the human dignity of recruits”. He harshly criticised the military authorities for their impassiveness, lack of understanding and irresponsibility in this regard.

Kalle Lohi

Variations on these accusations were subsequently delivered by MPs from the other non-socialist parties. MP Kalle Lohi of the Agrarians saw a connection between the unjust collective punishments and why youngsters of good character resorted to “poisonous vices” in the barracks – they sought “some comfort in their miserable and desolate existence”. Even MP Juho Mannermaa of the conservative National Coalition Party, usually the most defence-friendly party in parliament, brought up the “ungodly barking”, “obscene name-calling” and “punishments bordering on downright torture” on part of the soldiers’ superiors. Mannermaa mainly blamed the bad conditions on insufficient funding and lack of competent personnel, but repeated Santeri Alkio’s claim that there was a “deep concern among the people” and that “fathers and mothers rather generally fear sending their sons to the barracks”. He proposed a statement that was passed in parliament, requesting the government to pay special attention to the disclosed shortcomings in the officers’ attitude to the men and take action to correct them.

The Social Democrats naturally piled fuel on the fire by continuing the catalogue of alleged malpractices and bad conditions; rotten food, soldiers freezing and falling ill in wet clothes and unheated barracks, soldiers commanded to crawl in muddy ditches or stand unprotected for hours in the burning sun, alcoholism and criminality among the officers, collective and humiliating punishments, and so on. In contrast to Alkio’s anti-Russian rhetoric, the socialists unequivocally pointed to Prussian influences as the root of all evil. The defence minister’s response to all the critique heaped on the military service system was surprisingly docile; he admitted that there were many deficiencies and pointed to newly started courses in military pedagogy for officers as a remedy that would need time to show results. However, he added, a certain heavy-handedness was in the nature of military education. “The soldier would be much more offended if he was treated like a young lady, and with good reason too.”

Conscripts as victims of military education

The argument that a bit of rough treatment was only salutary for young men, hardening them for both war and peace, was not, however, generally accepted in Finnish society as a sufficient explanation for the scandalous conditions in military training. As indicated by the press cuttings on military matters from Swedish-language newspapers in the Brage Press Archive, including summaries on major topics in the Finnish-language press, the poor sanitary conditions and reckless treatment of conscripts were labelled highly dangerous to the conscripts’ health, detrimental to the will to defend the country, and thus absolutely unacceptable, throughout the 1920’s. This was the case even in bourgeois layers of society that were at pains to emphasise their preparedness to make great sacrifices for the nation’s defence. For example, the above-average mortality rates among conscripts were the subject of many articles in 1928–1929.

The chief medical officer of the armed forces V.F. Lindén himself stated that one reason for the high mortality were the excessively hard exercises in the initial phase of military training. The fearfulness of parents sending their sons to military service, the anti-militarist and embittered spirit of recently disbanded young men, the unpopularity of the conscript army, and disappointed amazement at the nonchalance of the army command in this respect were recurrent images in editorials on military matters.

In this, the portrayal of Finnish conscripts is far removed from the bold images of natural warriors of the Civil War. Here, conscripts are the defenceless victims of incompetence, moral corruption and sheer brutality among their superiors. They fall ill or even die in the military, but their deaths are not in the least heroic, only tragic and meaningless. The soldiers are often described as beloved sons, hardly more than children, and the press commentaries foreground the concerns and grief of their parents as their sons return home with a ruined health or morality. These conscripts are portrayed as boy soldiers, incapable of autonomous agency in the ironcage of military discipline. They are beyond legal protection, given into the care and custody of officers who fail the responsibility entrusted with them.

The turn of the tide

The Army seems to have been very limited in its public information services in the 1920’s, reluctant to accept the “meddling” of civilians – such as members of parliament – into the details of military matters. According to press reports, they were slow to react to the vehement criticism of military education. Yet in the years around the turn of the decade 1930, an inconspicuous but decisive shift in the negative public image of the conscript army took place. The press reports on disgraceful conditions in the army grew scarce. This evidently had several reasons. First and foremost, the material conditions in the army gradually improved with increasing funding and ever-larger defence budgets. Better equipment and food could be afforded, barracks were built and repaired and training approaches and methods changed rapidly. The professional and educational competence among the officer corps rose as the officer training system developed and new military curriculum were introduced.

New efforts were also made at public relations work within the armed forces. The army finally reacted to its image problem by starting to arrange “Family days”. In these events, the conscripts’ relatives could visit the garrisons and training camp, observe the soldiers’ living conditions, witness combat shows and listen to speeches by officers and politicians. A press bureau was set up at the General Staff Headquarters in 1929, a post as liaison officer between the armed forces and the press was created in 1933, and in 1934 an office for active information services was established. From 1934 on, the Army worked closely with the Suojeluskunta to produce short films on various military-related topics which were shown in cinemas around the country, doing much to raise the image of the Army and increase support for defence spending and the Armed Forces (we will touch more on this subject when we come to look at the Suojeluskuntas and Lotta Svard organisations in more detail. There was also a new bid to invite press representatives to observe large maneuvers, which resulted in large, excited and positive reportage in the newspapers.

The armed forces also entered into co-operation with the national film company Suomi Filmi to produce a series of there own motion pictures where a positive image of the conscript army provided the setting for humorous adventure. In the political arena, the Social Democrats and their voters found an increasing number of things worth defending in the Finnish national state. Land reforms in 1918–1922 had made small farmers out of many former tenant farmers and farm workers. Labour market legislation as well as social reforms strengthened the burgeoning welfare state. The Finnish economy grew rapidly at an average annual pace of 4% through the 1920’s and 1930’s, bringing Finland from relative poverty to a level of prosperity on a par with the Netherlands and France. Although this wealth was unequally distributed, the living standards and real wages of Finnish workers rose considerably in the 1920’s and after a slump during the Great Depression rose again in the latter half of the 1930’s.

Ever since their return to parliamentary politics after the Civil War, the moderate wing among the Social Democrats wanted the party to take a more positive attitude to national defence. The party press printed articles attesting that the workers were ready to fight alongside the other classes to defend independence. Complete disarmament was still said to be the socialist ideal, but this could not come about as long as the “danger in the east” remained – indeed not before socialism was realised in the whole world. A left-wing pacifist tradition within Finnish social democracy continued to compete with the more centrist and pragmatic approach to national defence throughout the 1920’s, but the social democratic MP’s acknowledged that Finland did need some kind of armed forces to protect its independence. The splitting of the Social Democratic party in 1920, and the subsequent entry of a new, far-left Socialist Workers’ Party in parliament in 1922, worked as a catalyst pushing social democracy closer to the political centre in this issue. “It makes a great difference to the working classes whether a foreign power can place Finland under its yoke”, MP Jaakko Keto stated in parliament that same year. “The class struggle of the workers can only be successful in a democracy based on the right of national self-determination.”

Jaako Keto: 1884-1947, Social Democrat MP

This right, Keto underlined, was neither self-evident nor unthreatened. This patriotic outburst was a reaction to an MP Socialist Workers’ Party who had claimed it was not in the workers’ and peasants’ interest to give any kind of support to the bourgeois army. Instead, the army should be organised as in the Soviet Union, where soldiers from the working classes elect their officers among themselves. This was an exceptional proposal, as the far-left socialists usually argued for diminishing or even dismantling the national armed forces and entering disarmament treaties with the Soviet Union and Baltic states. Since the far left was usually understood as purely “defence nihilist”, its influence on the politics of conscription was limited to keeping the image of a domestic revolutionary ‘red threat’ alive.

Historians have designated the first post-civil war social democratic government, appointed in December 1926, to be a decisive turning point in the Social Democratic Party’s relationship to the regular army. One event in particular, the parade commemorating the white victory in the Civil War on May 16th 1927, was highly charged with symbolic meaning. The President of the Republic Lauri Kristian Relander had fallen ill and the social democratic Prime Minister Väinö Tanner agreed to preside over the parade – an occurrence that was dumbfounding for many people both of the political right and left. According to Historian Vesa Saarikoski, the reactions in the social democratic press expressed an acceptance of the regular army, but a bitter critique of the participation of General Mannerheim and the Suojeluskuntas. The latter were still at that time too strongly associated with the “white” tradition for many and the memories of the Civil War were still bitter.

16 May 1927 – Pääministeri Väinö Tanner valmiina vastaanottamaan suojeluskuntien lippupäivän paraatin vt. presidentin ominaisuudessa

16 May 1927: the social democratic Prime Minister Väinö Tanner agreed to preside over the parade commemorating the white victory in the Civil War after President of the Republic Lauri Kristian Relander had fallen ill – in a highly symbolic moment that was dumbfounding for many people both of the political right and left….

This right, Keto underlined, was neither self-evident nor unthreatened. This patriotic outburst was a reaction to an MP Socialist Workers’ Party who had claimed it was not in the workers’ and peasants’ interest to give any kind of support to the bourgeois army. Instead, the army should be organised as in the Soviet Union, where soldiers from the working classes elect their officers among themselves. This was an exceptional proposal, as the far-left socialists usually argued for diminishing or even dismantling the national armed forces and entering disarmament treaties with the Soviet Union and Baltic states. Since the far left was usually understood as purely “defence nihilist”, its influence on the politics of conscription was limited to keeping the image of a domestic revolutionary ‘red threat’ alive.

Historians have designated the first post-civil war social democratic government, appointed in December 1926, to be a decisive turning point in the Social Democratic Party’s relationship to the regular army. One event in particular, the parade commemorating the white victory in the Civil War on May 16th 1927, was highly charged with symbolic meaning. The President of the Republic Lauri Kristian Relander had fallen ill and the social democratic Prime Minister Väinö Tanner agreed to preside over the parade – an occurrence that was dumbfounding for many people both of the political right and left. According to Historian Vesa Saarikoski, the reactions in the social democratic press expressed an acceptance of the regular army, but a bitter critique of the participation of General Mannerheim and the Suojeluskuntas. The latter were still at that time too strongly associated with the “white” tradition for many and the memories of the Civil War were still bitter.

Kuolemaantuomitun hyvästijättö

Halki ilman kuolon kellot hiljaa kumajaa, kun tuonen viikate tuo julma niittää saalistaan.

Nyt murhe raskas sydämiä kaivelee ja polkuja tuonen viitoittaa se kyynelin.

Älä itke äiti kadonnutta lastasi, vaikka sulta riistetty on ainoo turvasi.

Niin huoles heitä, toivees heitä kaikki unholaan. Ja oota kunnes iäisyydes’ tavataan.

Hyvästi aatetoverit, te harhailette viel’, haaveillen tietä kuljette te aamun koittoon siel’.

Ei tiedä konsa hetki lyö ja silloin koittaa yö. On unikuva elämäin ja raukee työ.

On kumpu metsän siimeksessä, jossa lepäjän. Ja hongat siellä virittävät mulle virsiään.

Ei kelloin ääni häiritse mun ikiuntani. Ei pappein siunausta kaipaa tomuni.

Kun kevät jälleen herättää taas kukat kummullein, niin linnut virttä lohdutuksen mulle laulelee.

Tää alttari on kärsineen ja hauta uupuneen, jonk’ kyynelhelmin kukat puhkee ilmoille.

Jos tiedon saat sä armaani mun kuolemastani ja tiedät missä sijaitsee mun lepopaikkani,

niin ruusu veripunainen haudallein istuta. Se kasvaa siinä aatteheni muistona.

Through the air of death the bells silently toll,

When Death’s scythe cruelly cuts down her prey,

Now the grief and heavy hearts,

Pave death’s trail with tears.

Do not cry, mother of a missing child,

Even if you have been stripped of your security,

There is no more worrying, hopes are all forgotten,

Wait until in eternity we meet.

Goodbye my comrades, you are wandering still,

Dreaming of the path we took, in the morning dawn,

I will not know when the moment strikes, then comes the night

I lived a dream and now my work has ended.

There is a mound in the forest’s shadows, where I rest,

And there old pine trees sing to me,

The sound of bells will not disrupt my eternal sleep,

And I need no priest blessing my earthly dust.

When spring flowers once again rise on my grave,

They will sing a song of consolation to me,

This altar is my sacrifice, a grave for the weary,

Whose pearly tears will blossom out as flowers

If the news comes to you my dear of my death,

And you know where is my place of rest,

Then put a blood red rose on my grave,

To grow there as a memory to my beliefs.

The far-left obtained 10–15% of the popular vote in the parliamentary elections from 1922 until their political activities were completely forbidden in 1930. The far left voiced a radical version of the socialist critique of capitalist militarism, wanted to abolish the civil guards and voted against all government proposals and appropriations in military matters. However, there was no parliamentary representation left of the Social Democrats during most of the major debates over conscription analysed here. The army was slowly ever more accepted by the Social Democrats as the defender of the whole nation, including the working classes.

Political convergence and the conscription bill of 1932

The parliamentary debate over the last conscription law of the interwar period, passed in 1932, demonstrated how the ranks were closing around the regular conscript army in its existing condition. The new law concerned a reform of the mobilisation system, where the responsibility of mobilising the reserve was taken off the regular army troops and transferred to a new organisation of regional military authorities, co-operating closely with the local branches of the civil guards. The objective was to free all available active troops in order to fend off an aggressor during the time it took to mobilise the reserve. As pointed out by Annika Latva-Äijö, this reform finally integrated the Suojeluskuntas (Civil Guard) and female voluntary defence workers (Lotta Svard) into the national armed forces to the full.

It signaled an end to the condescending attitude of professional officers to the voluntary defence organisations and in a sense constituted a transition to a mixed form of a Cadre Army with Militia elements that would become an ongoing trend through the 1930s as more changes took place. The tone of the following debate was very different from that in 1921-22. There was no more debate over the basic principles of the military system. The bill was passed relatively rapidly. The Social Democrats main criticism was that the length of service was only nominally shortened. However, this time around, the socialist MPs were keen to demonstrate that they were as patriotically concerned about national defence as anybody else. They embraced the core of the reform, supported increased military spending and did not bring up the militia system as an alternative any more. Arguing for some alterations to the bill, providing for a shorter active service compensated by more refresher courses, they emphasised that their own proposals would actually strengthen national defence.

There was some debate over the role of the Suojeluskuntas within the armed forces but following the historic rapprochement between the Suojeluskuntas and the Social Democrats that we have already touched on, this was muted and almost inconsequential. The Social Democrats did however include provision for recurrent military training for all reserve soldiers; training of the kind that the Suojeluskuntas had only given to a part of the population, excluding anybody associated with the workers’ movement. The greatest benefit of the social democratic counter-proposal, said MP Matti Puittinen, was that “in this way we can think the of the Suojeluskuntas as a Finnish organisation that is now non-political and dedicated to the defence of all Finns. We can now trust the Civil Guards because we ourselves, the workers of Finland, are now also Civil Guards.”

Just before the reading of the 1932 conscription bill started, the popular extreme-right Lapua movement had staged the so-called Mäntsälä rebellion. The Lapua movement demanded that the Social Democratic Party should be forbidden, just as the communists had been in 1930. The Mäntsälä rebels declared their readiness to override the lawful form of government if necessary to reach this goal. Some local commanders of the Suojeluskuntas sympathised with the rebellion and tried to mobilise their guardsmen. The result, however, was pitiful. The attempted rising never grew beyond 6–8000 men gathering at rallying-points around the country – only a small percentage of the hundred thousand + guardsmen. President of the Republic Per Svinhufvud, Commander in Chief Aarne Sihvo and several central ministers resisted the rebels’ demands. So did the centrist moderates in the local civil guards throughout the country, not least those affiliated with the Agrarian Party. In the end (we will cover this in more detail in a separate post), the rebellion was wound up peacefully with the support of the Army and the vast majority of the Suojeluskuntas going to the Government.

In general, the non-socialist MPs did not find much to debate in the 1932 conscription bill. The comments of the agrarian Minister of Communications Juho Niukkanen, an active figure within parliamentary defence politics ever since 1915, were indicative of the emerging convergence around the national armed forces. He pointed out that the differences of opinion regarding the bill itself were actually relatively small. For the first time, Niukkanen stated, even the Social Democrats argued over national defence “on quite a relevant and no-nonsense basis”. There had been a decisive shift in favour of the regular army within both the left and the centre. The army had proven its democratic reliability in the interest of all layers of society during the rebellion.

The 1932 bill was passed unaltered and Finland acquired its final prewar conscription law. As far as the legislation process was concerned, the politics of conscription had reached its interwar terminus. During the rest of the 1930’s, military politics in parliament turned around the issue of how much money should be spent on military acquisitions and further reforms in training and organisation. The Social Democrats supported a number of supplementary grants for national defence, and after they entered a large centre-left coalition government in 1937 and in face of the tightening international situation they were a key participant to the approval of major defence spending increases. Regardless, from 1930 on the Social Democrats programme essentially supported a strong defence based on the existing conscript army system.

Reluctant militarisation

A drawn-out process of “normalisation” and growing national consensus came to characterise the politics of conscription. The standing conscript army slowly became something increasingly normal to Finnish society. The demands conscription made on men gained strength, not only as an institutional but also as a political and civic norm. However, as the previous posts have demonstrated, the militarisation of Finnish society was no self-explanatory function of national independence or originating in some inherent fighting spirit of Finns. Rather, it was the outcome of a decade-long political struggle entangled with the re-arrangements of political power in the new Finnish state. It is remarkable that the debates over conscription in parliament and in the press seldom explicitly referred to citizenship.

The fact that both men and women had been fully enfranchised for more than a decade when universal conscription was introduced might have kept at bay images of military service as a prerequisite for citizenship in general. The question of inclusion or exclusion in the political community only surfaced in connection with the issue of special treatment of “untrustworthy”, politically subversive conscripts. The Social Democrats’ enragement over unequal treatment of conscripts on political grounds showed that whatever their critique of society and the military system, they were anxious to be included and allowed full civic participation in the political community of state and nation – and in the armed forces.

Implicitly, however, the political fight over a people’s militia versus a standing cadre army conveyed contesting images of the duties and rights of Finns towards the political community. The Agrarians initially could not accommodate a military system constructed according to models from imperial Prussia and Russia with their idealised notions of Finnish society and culture. The militia alternative they offered had many elements strongly reminiscent of the civic-republican tradition with its notions of “free and brave” citizen-soldiers who voluntarily fought to protect their rights and their property. Nonetheless, in light of the threat from Bolshevik Russia, the Agrarians were receptive to arguments stressing the military efficiency of the Cadre Army. Concerns about the loyalties of domestic socialists made the promise held out by the Cadre Army, of discipline and control over conscripts given weapons, more tempting than repulsive. One crucial issue remained – the political inclinations and loyalties of those in immediate command of the Cadre troops, i.e. the Officer corps. As we shall see, this question was resolved to the Agrarians’ satisfaction by the mid-1920’s.

In the conscription debates, the Social Democrats were more intent on constructing the standing army soldier as a countertype than on detailing their positive ideal for the citizen-soldier. Nevertheless, their image of barracks life as morally corrupting reflects the working-class movement’s moral agenda for a temperate, steady and conscientious worker. Their claim that military training turned conscripts into blind lackeys of capitalism, “hired murderers” oppressing their own class, implicitly expressed the alternative vision of politically aware, strong-willed workers. These dimly outlined socialist citizens were certainly fighters, although there were different views within the movement on the righteousness of armed violence. Yet their fight was and just only if they fought for their own class and their own true political and economic interests, out of their own autonomous free will and a clear political awareness – not as the mercenaries of their own oppressors.

The conservatives and liberals were less verbose in the conscription debates. Since they supported the status quo and backed the government proposals in the matter, they had less need to talk about conscription. Whether they consciously strove for the disciplining of the masses associated with the Prussian conscription system or not, at least they did not object to it. The notion of conscripts educated into patriotism and dutifulness, submitting their personal interests to the higher cause of the national state, suited conservative values; and the liberals were probably too concerned about external and internal security to make any objections on grounds of liberal principles. The relative silence on the right side of the parliamentary chamber also indicates that conservative and liberal MPs felt they had the support of their constituencies for the conscription policies enacted.

However, the most important conclusion from this exploration into the politics of conscription concerns the reluctance and hesitance of Finnish politicians in relation to the military solutions offered by the military establishment. Parliament had no control over the process as the national armed forces were created and was essentially faced with fait accompli as it reassembled in the summer of 1918. Over the years to come, a good number of its members sought to curb the sudden militarisation of the Finnish state and conscripts’s lives, trying to put limits on military expenditure and cut the length of active military service. Although a large parliamentary majority in the course of time came to accept a standing conscript army, this military system was seldom glorified or celebrated in parliament in the same way as the feats of the White Army in 1918.

On the contrary, the parliamentary records abound with expressions of concern about the negative effects of this system on the nation’s economy, on conscripts’s career path and on the morals of the conscripts, as well as scepticism about the political loyalties of the officer corps. These concerns and doubts were mainly expressed by the popular mass parties of the political left and centre, but even the conservative and liberal MPs mostly described the regular army and the conscription system as a regrettable necessity, rather than as a school in nationhood or a vehicle of national re-integration. They also voiced public concerns over bad conditions for the conscripted troops when these concerns were running high among their voters.

The views expressed in parliament are indicative of a widespread scepticism and lack of enthusiasm among large segments of the civilian society; a scepticism about conscription in general and especially about the Russian- and/or Prussian-style cadre army, its officer corps and its impact on conscripts. However, as the parliamentary debates also indicate, this scepticism was neither monolithic nor static, but shifted over time and was relative to perceptions of alternative security solutions, threats to ordinary citizen’s lives, and prospects of success in fighting these threats. Fundamental doubts as to the moral justification of the state expropriating one or two years of conscripts’s lives were, however, not voiced any more after the Civil War. Agrarians and Social Democrats mainly used fiscal and military arguments for a shorter duration of military service. What was not really contested by anyone was that young fit men were to be compelled to take upon themselves the burden and sacrifice of fighting and falling, killing and dying, for the nation’s defence.

There would be substantial changes through the 1930’s, both within the military in the way conscripts were educated, trained and treated, and in the way both politicians and citizens came to see the military. Combined with the rapprochement between the Social Democrats and the Suojeluskuntas, attitudes would change significantly, as we will see. However, Conscription in Finland would remain unchanged – military service would continue to be seen as an obligation and duty of citizenship – a view that would become ever more pronounced over the years as the military was seen as a “national” institution.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland