Finnish Volunteers in the Estonian War of Independence

Finnish Volunteers in the Estonian War of Independence consisted of two groups. They were I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko (1st Finnish Volunteer Corps) commanded by the Swedish Major Martin Ekström, and Pohjan Pojat (“The Boys from the North”) commanded by Colonel Hans Kalm. Finnish Army Major-General Martin Wetzer was the Commander-in-Chief of both units.

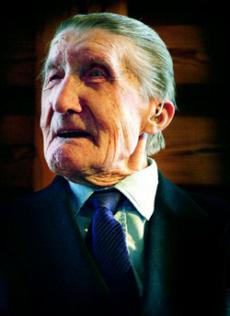

Paavo Takula – last surviving veteran of Pohjan Pojat

Incidentally, the last survivor of the Finnish volunteers in the Estonian War of Independence, Paavo Takkula, died in 2004. Paavo Takkula was one of 4,000 Finnish volunteers, 175 of whom were killed and 250 wounded over the course of the fighting in Estonia. Takkula joined the Volunteers even though his mother asked him not too. “I went because my father and brothers went,” he explained. The Takkula family paid a heavy price fighting for Estonia’s freedom. His father and older brother went missing and another brother was killed. “The Soviet Navy shot at us from a large warship, our bunker was hit by a shell, and Mikko was hit by a 12-inch shell fragment,” recalled Takkula. His brother lived for two weeks with a broken backbone before dying from his injuries. The attack also resulted in Paavo losing the hearing in one ear.

I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko / 1st Finnish Volunteer Corps (Finnish Volunteers in the Estonian War of Independence)

The 1st Finnish Volunteer Corps was a Finnish military volunteer group who participated in the Estonian War of Independence in 1918 – 1919. The 1,550 man-strong regiment was commanded by the Swedish Maj. Martin Ekström, formed up in Finland in December 1918 and was transported to Estonia on the 30th December 1918.

The Bolshevik forces had been making rapid progress up until the arrival of the battle-hardened and experienced Finnish troops. The arrival of the Finns triggered the arousal of the Estonians fighting spirit, and this together with the experience of the Finnish troops enabled the Estonians to achieve their first victories.

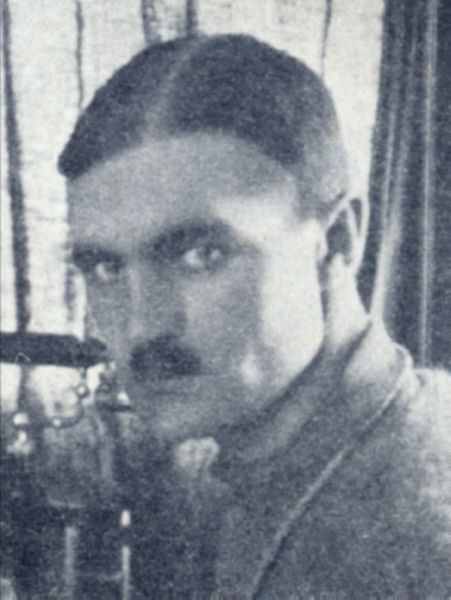

Swedish Major Martin Ekström, commanding officer of 1 Suomalainen Vapaajoukko

Estonian Communist Party Leader Jaan Anvelt (1884-1937). Anvelt was arrested by the NKVD in 1937. Interrogated in custody, he died from the injuries inflicted by an interrogator named Langfang on 11 December 1937, and was denounced as an enemy of the people afterwards.

Incidentally, the Bolshevik forces also included many Finns from the Red Guards and to a certain extent, the fighting turned into a continuation of the Finnish Civil War fought in northern Estonia. I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko attacked vigorously, capturing Rakvere on 12 January 1919. This was followed by a successful seaborne attack (transported by the Royal Navy) by 500 volunteers on Narva on 17 January.

The taking of Narva was the most important military achievement of I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko in the Estonian War of Independence. The volunteers lost ten men killed, two missing and thirty-forty wounded in the action against a Bolshevik force many times larger which fled in panic. Trotsky and the Estonian Communist leader Jaan Aanveltia were in Narva at the time and barely escaped capture. The remainder of the Finnish and Estonian forces arrived the next day and assisted in clearing the city of the enemy remnants. In the clearance operation, 27 Red Finns were captured and subsequently executed in front of the Narva City Hall. The capture of Narva was a humiliating defeat for the Red Army and an inspiration to the nascent Estonian forces. The capture of the city also captured the attention of the foreign press and made news around the world.

The C-in-C of the Estonian Army, Johan Laidoner, promoted Ekstrom to Colonel after the victory and requested that the Finns continue the attack into Western Ingria. However, the overall commander of the Finnish volunteers, Major General Wetzer did not want volunteer forces to exceed the Estonian national borders. The Estonian/Finnish forces therefore held the line of the Narva-Peipsi until the end of the war while Estonian and White Russian forces continued to advance further into Russia, reaching the approaches to St Petersburg and capturing Pskov, which was occupied by the Estonian army between February 1919 and July 1919.

Estonian troops cross the Velikaya river taking over Pskov. Pastel by E. Brinkmann

After the capture of Narva, I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko was no longer involved in large operations and withdrew to a reserve position at Rakvere before being disbanded in March. Overall, I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko lost only 31 men, a very low number. Aside from skill and experience, the units advantages had been their unshakable faith in victory, and their ability to achieve the element of surprise in battle.

Pohjan Pojat (The “Boys from the North” – Finnish Volunteers in the Estonian War of Independence)

Pohjan Pojat (the “Boys from the North”) were the second of the Finnish Volunteer Units to participate in the Estonian War of Independence. While the first Volunteer Unit (I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko / 1st Finnish Volunteer Corps) was larger and arrived in Estonia earlier, Pohjan Pojat achieved a legendary reputation, fighting on the Southern Front all the way to the Estonian border under the command of Colonel Hans Kalm.

Colonel Hans Kalm

Hans Kalm was an officer with experience from serving in the Russian Army (he was drafted in 1914 as an NCO, promoted to Lieutenant in 1915, attended Hatsinan Aviation School as a trainee. From December 1915, Kalm had served on the Galcian Front and had acted as the Battalion Commander. He was wounded in action four times, awared decorations for bravery and was promoted to Staff Captain in July 1916. When the Bolshevik Revolution broke out, Kalm escaped with the assistance of Romanian Officers and reached Estonia in late October 1917. In Estonia, he worked to assist in setting up an Estonian Army but after “difficulties” with the Russians and local Estonian communists (his house was burnt down) he escaped to Finland, where he worked in Lapland and Northern Finland under the pseudonym John Kontiomäki, helping establish Suojeluskunta units.

When the Finnish Civil War broke out in late February 1918, he gathered students and volunteers into the Northern Häme I Battalion, which he commanded. The battalion fought well under his leadership and towards the end of the Civil War he was promoted to Major in March 1918. Forces under his comman played an important role in the liberation of the city of Lahti. His battalion was somewhat notorious for the executions of Reds that were carried out during the Civil War. After the fighting was over, Kalm’s battalion guarded a Prison Camp at Hennala for Red PoW’s, where they executed some 500 Reds.

Colonel Hans Kalm and his Officers – Kalm is centre front, to his right is Chief of Staff Elja Rihtniemi

Writer and researcher Tauno Tukkinen has documented that of these executions, some 200 were women and children with an average age of 20 years (Tukkinen identified that the executed women ranged from 30 to 17 years old, including Nurses, with 25 girls younger than 17 executed. The youngest were 14 and 15-year old children). Kalm’s unit executed more Reds that any other White unit in the Civil War and similarly, executed more women than any other White Force. Almost all the killings of women were in the first two weeks of May, after which Kalm’s unit was transferred in late May to Hämeenlinna. Shortly after this the battalion was dissolved and Kalm resigned from the Finnish Army in July 1918 (he had been promoted to lieutenant colonel). He was promoted to full Colonel in August 1918 and received Finnish citizenship in 1918.

As soon as the Committee to Aid Estonia was set up and the decision was made to form Volunteer formations, Kalm began recuiting volunteers. Volunteers over the forst few weeks were assigned to I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko rather than to the more outspoken Kalm. On the 23rd Dec 1918 Kalm published a series of outspoken and emotional recruitment advertisements in Finnish newspapers in which he appealed to veterans of the Finnish Civil War, asking Finns to fight for humanity, justice, patriotism and to assist their brothers in Estonia.

Finnish volunteers arrive in Tallinn Estonia in December 1918

Meanwhile the Committee to Aid Estonia had decided that another thousand men should be sent to assist the Estonian forces under Kalm. Kalm however was not particularly interested in the force size limitation and recruited around 2,300 men, creating the equivalent of a strong Regiment or a small Brigade with two infantry battalions, three Artillery Batteries, Signals, Cavalry and Ski sections. The 1st Battalion was commanded by Jaeger Lieutenant Erkki Hannula while the 2nd Battalion was commanded by Captain Gustav Svinhufvud.

Pohjan Pohjat suffered from equipment and financing problems, which meant that while the first members of Pohjan Pohjat arrived in Estonia on 7 January 1919, the 1st Battalion did not complete arrival in Tallinn until 12 January 1919. They received a much warmer welcome than I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko due to the victories the earlier-arriving unit had achieved, being greeted on arrival by Estonian army chief Colonel Johan Laidoner, Estonia-Finland Volunteer Commander Maj. Gen. Martin Wetzer and the Estonian Minister of War, Konstantin Päts.

Following their arrival, Pohjan Pohjat moved from Tallinn to Tartu on the southern front on 27 January 1919, which had been recently recaptured from the German Baltic Landswehr forces. Their first operation was against heavily armed Latvian Red Army forces on 31 January, where they fought together with the Estonian Julius Kuperjanov Partisan Battalion and Estonian armored trains in a bloody first battle at Paju Manor, during the course of which the 1st Battalion suffered heavy casualties, losing one officer, two NCO’s and 21 soldiers.

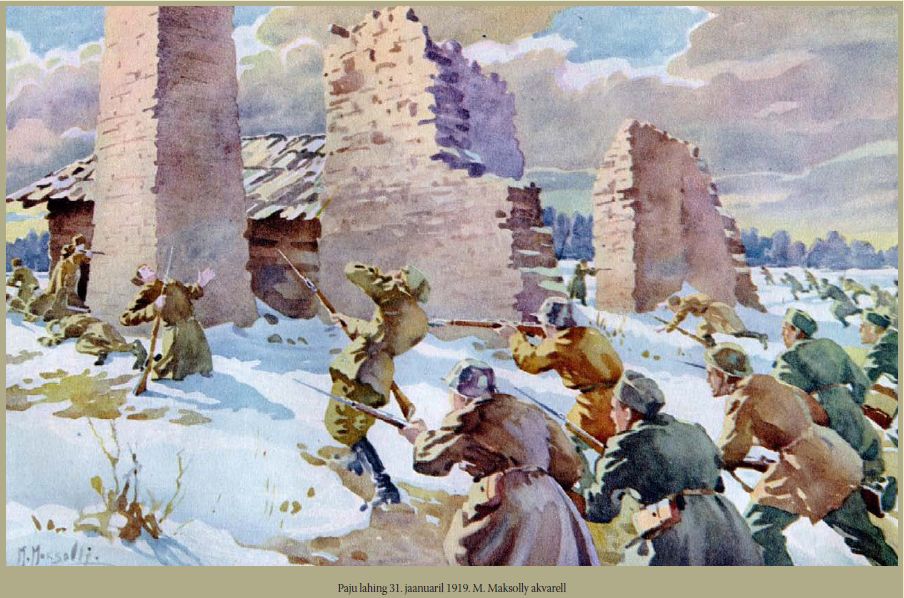

The Battle of Paju Manor

In early January 1919, Estonian forces had started a full scale counterattack against invading Soviets. Their main objective was liberating north Estonia including Narva, which was achieved by January 17. They then started to advance into south Estonia. On January 14, the Tartumaa Partisan Battalion, organised and led by Lieutenant Julius Kuperjanov, and armoured trains liberated Tartu. At that time the only working railway connection to Riga, which the Red Army had captured on January 3rd, passed through Valga, so defending Valga (in southern Estonia) had strategic importance for Soviet Russia. The Red Army sent a number of units to defend Varga and halt the Estonian advance, including a large part of the elite Latvian Riflemen. Estonian Commander-in-chief, Johan Laidoner reinforced the Estonian advance in the south, sending Pohjan Pojat under the command of Colonel Hans Kalm. Finnish General Paul Martin Wetzer was appointed the commander of the southern front.

To liberate Valga, it was necessary to capture Paju Manor. On January 30, Estonian partisans had briefly captured it, but were soon pushed out. With his 300 men, 2 guns and 13 machineguns, Kuperjanov decided to recapture Paju on January 31. Armoured trains were unable to support Kuperjanov’s unit, due to the destruction of the Sangaste railway bridge. The Latvian Riflemen holding Paju Estate had about 1,200 men with 4 guns and 32 machineguns. They were also supported by an armoured train and armoured cars. The Tartumaa Partisan Battalion attacked the estate directly over open fields. At 400 metres the Bolshevik troops opened fire, inflicting heavy casualties. Kuperjanov led the attack personally, as was his usual practice, and was fatally wounded, dying two days later. After Kuperjanov was hit, Lt. Johannes Soodla took command of the battalion.

Battle of Paju on January 31 1919. Watercolour by M. (Maksimilian) Maksolly

A little later in the day, Pohjan Pojat units with about 380 men arrived, bringing with them 4 guns and 9 machineguns. They also assaulted the estate in a frontal attack which caused heavy losses. In the evening the Estonians and Finns finally pushed into the park of the estate where heavy hand-to-hand combat took place, resulting in the defeat of the Bolsheviks and the capturing of the estate. The retreating Latvian Riflemen were subjected to heavy fire. On the next day the Estonians and Pohjan Pohjat units liberated Valga without resistance. The victory cut off the Soviets’ railway supply line and denied them the use of armoured trains. Soon almost all southern Estonia was liberated and Estonian troops advanced into northern Latvia. The Battle of Paju was the fiercest battle in the early period of war. To honour Julius Kuperjanov who died of his wounds on February 2, Tartumaa Partisan Battalion was renamed Kuperjanov’s Partisan Battalion.

Pohjan Pojat continued to fight the Latvian Red’s at the side of the Estonians, but a number of the volunteers were instructed to remain in reserve at Valkiin until the command to move into northern Latvia was give. Kalm grew tired of waiting and ordered his soldiers to attack the northern Latvian city of Marienberg (Aluksne) on 16 Feb 1919. Finnish volunteers were not supposed to operate outside of Estonia’s borders but despite this, Pohjan Pojat moved out on 19 Feb and arrived near Marienberg on the evening of Feb 20. At dawn on Feb 21st they started their attack without any support. Pohjan Pojat captured the city with the loss of 3 officers and 15 soldiers, after which some looting took place. Estonian armored trains arrived on 22 Feb and on the 23rd, Estonian troops took over the City. On Feb 24th a Victory Parade took place, subsequently Pohjan Pojat withdrew and returned to Estonia on Feb 26th, where they moved into the Reserve at Valkiin.

In mid-March 1919, Pohjan Pojat were sent to the St Petersburg front, where the Bolsheviks had begun a counter-attack. They fought there until the end of the month, then returned to Valkiin at the end of March. In this last major fight that the unit participated in, they lost 27 dead, eight missing and nearly 100 wounded. Kalm then wanted to commit Pohjan Pojat to the Ingrian cause but the majority of the soldiers at this stage wanted to return home to Finland. Most of the soldiers of Pohjan Pojat were repatriated back to Finland in early April 1919. Kalm remained in Estonia with 200 men, with whom he hoped to establish the beginnings of an Ingrian volunteer army. These 200 soldiers participated in the fighting of April-May but in the end did not move into Ingria and the Committee to Aid Estonia Päätoimikunta terminated Kalm’s employment. Kalm disbanded the regiment on 29 May 1919. After dissolution some of the men continued to serve with the Ingrians’ and some with the Estonian Army.

Ingria

Georg Elfvengren, commanding officer of the North Ingrian Regiment

However, Kalm was not the only officer with ambitions towards Ingria. The region around St. Petersburg had been a historical gateway between Estonia and Finland, forming the easternmost part of the Finnic populations living around the Gulf of Finland. Like the Estonians and Finns, the Ingrians were Lutherian people who spoke a language that was classified as a dialect of Finnish. They were mostly descendants of immigrants that had moved from Finland during the time when the region had been under Swedish rule – after the establishment of St. Petersburg they had stayed on their old villages located to the countryside around the growing new capitol of Russia. Now this 200,000 strong community suddenly found itself living in the vicinity of the new center of Bolshevik power.

After the Finnish Civil War the leaders of the failed revolution from Finland had fled to Petrograd, where they soon created the SKP (Communist Party of Finland). Lenin tasked this group to organize all the Finnic peoples of Russia to support the Soviet war effort, and naturally the organizers of SKP started their work from Petrograd and surrounding Ingria. Conservative elements in the Ingrian population resisted this development, and by spring 1918 small groups of armed Ingrian guerrillas had established their presence in the border parish of Kirjasalo next to the Finnish border on the Karelian Isthmus.

This small local rebel band was soon swept up in a major conspiracy involving top levels of Finnish Government. During the stormy year of 1919 Finland had indeed held two elections that had dramatically changed the political situation within the country. On the insistence of United States, Britain and France, Finland was due to have “new, free parliamentary elections.” That meant that the SDP was allowed to campaign as well. Despite the understandably icy and tense atmosphere of the election process, the elections (under international supervision) went off without major fraud and the SDP remarkably maintained the position of strongest party with 80 seats, despite the loss of twelve when compared to the previous election.

Even though the SDP was left in opposition, the new political situation in the country no longer enabled the Conservatives to conduct foreign policy as freely as during the previous year. When the decision to let the Eduskunta elect the first President of the country was approved and the election approached in summer 1919, the supporters of a more aggressive policy towards Russia began to conspire behind the scenes. These groups were based on the contacts of pre-independence Activists who were now aiming their activities against the growing threat posed by Bolshevik government and their presence in Petrograd.

The conspirators knew that in order to gain support for their plans, they would have to support Mannerheim for President. The former commander of the White forces was however strongly opposed by the SDP, and would surely lose the summer elections unless something major took place near the borders of Finland. As the months went by, secret shipments of weapons and supplies begun to trickle through the border on the Isthmus to Kirjasalo, and recruiters were soon circulating in Ingria and Finland, gathering suitable men to join the newly established “Regiment of North Ingria.” This force was led by a somewhat eccentric veteran officer of the Civil War, Georg Elfvengren, who had joined forces with the Activist plotters for his own reasons.

Like Hans Kalm in Estonia, Elfvengren was a former officer in the Russian Army and hated Bolsheviks like poison. He wanted to see them driven out from Petrograd, and figured that the fully mobilized Finnish Army could to the job. But a casus belli was needed to justify any intervention against the Bolshevik capitol, and here Elfvengren and his Ingrians came in to play. They were tasked to invade Ingria from the Isthmus, “encouraging the locals to join in a wide uprising” that would create similar feelings of empathy and calls for intervention as the Red Army invasion of Estonia had done. In this situation Mannerheim could win the elections, declare martial law, mobilize the Army and march to Petrograd.

Elfvengren gave the order to attack the day before the Eduskunta gathered to vote, and immediately afterwards he wired all the major Finnish newspapers and radio stations, declaring that “Ingria had arisen against the Bolshevik terror.” The poorly armed and trained Ingrian volunteers who marched southwards in those critical days of June were opposed by Red Army units that were ironically composed of Finns of St. Petersburg and Ingrians from the surrounding countryside. Just as in Eastern Karelia and Estonia, the locals were fighting amongst themselves while the major powers played their own games at a higher level. The invasion failed miserably, and the public mood was more surprised than shocked. Mannerheim was still widely despised among the SDP members and distrusted by the Agrarian Union, he lost the election decisively to K. J. Ståhlberg on 26th of July 1919.

For the next year the North Ingrian Regiment and Elfvengren used the region of Kirjasalo as their base, fighting what was more or less a private war against the local Bolshevik Ingrian units defending Leningrad. By now the situation in Finland and more importantly in Russia was stabilizing somewhat, and attempts to change the borders in Eastern Karelia were looking increasingly unlikely due the fact that the Eduskunta was once again dominated by the SDP. Lenin wanted to secure his northern flank, while Finland wanted to solve the uncertain “undeclared war” status between Finland and the Bolsheviks. As border negotiations got underway, Ingria was not even among the discussed topics even though the Bolshevik government had stated that it would respect the local wishes for autonomy both in Eastern Karelia and in Ingria. As the Russo-Polish War was drawing to an end, Finland and the Bolshevik Government signed the Treaty of Tartu on 14 October 1920 after four months of complex negotiations. The North Ingrian Regiment withdrew to Finland to be disarmed and demilitarized, and the situation along the borders seemed to finally calm down.

The Influence of the Heimosodat on the development of Finnish Military Doctrine

The experiences of the Heimosodat had a strong influence on the evolution of the Finnish Army’s strategy and tactics as they were developed through the 1920’s and 1930’s. Many of the writers of the first training manuals and future senior officers of the Army in the Winter War were men who had been trained through the German system, which emphasized the competence and initiative of the NCOs, while their war experience was a unique mixture of trench warfare on the Eastern Front followed by the experiences of the Finnish Civil War and the Heimosodat in Estonia, Ingria and Eastern Karelia.

Jaeger Officers and NCO’s who had fought with the Germans against the Russians would come to dominate the new Finnish Army

Värväreitä ja etappimiehiä: vasemmalta ylhäältä: jääkärimajuri Kurt Wallenius (käytti nimeä Aarne Pursiainen), kapteeni Urho Sihvonen (Oravapoika), majuri Lennart Oesch (Johansson), vänrikki Väinö Sutinen (Blomberg), kapteeni Erkki Viitasalo (Torniaisen Ville), kapteeni Tauno Ilmoniemi (Möttönen) ja vänrikki Eino Koivisto (Aho); keskirivissä: kapteeni Friedel Jacobsson (metsänhoitaja Borg), maisteri H. Stenberg, vääpeli Väinö Heikkinen (Hallan Väinö) ja tohtori Valter Sivén, alarivissä: kapteeni Aarne Salminen (Virén), vääpeli Savolainen ja Vääpeli Vilkman. Kuva: Tukholma tammikuu 1917 / From top left: Major Kurt Wallenius (using the name of Aarne Pursiainen), Captain Urho Sihvonen (Oravapoika/Squirrel Boy), Major Lennart Oesch (Johansson), Lieutenant Väinö Sutinen (Blomberg), Captain Erkki Viitasalo (Torniaisen Ville), Captain Tauno Ilmoniemi (Möttönen) and Lieutenant Eino Koivisto (Aho), middle row: Captain Friedel Jacobsson (metsänhoitaja Borg), Mr. H. Stenberg, Warrant Officer Vaino Heikkinen (Halla Väinö) and Dr. Walter Sivén, bottom row: Captain Aarne Salminen (Viren), Sergeants Savolainen and Vilkman.

The fast-paced and relatively mobile (by WWI standards) small unit combat of the Finnish Civil War and the Heimosodat led to the stressing of the importance of a high standard of marksmanship, good use of camouflage and most importantly, the use of terrain. The ambushes, hit-and-run raids and constant maneuvers that had defined these conflicts were now taken and used in Army training plans. As noted before, the emphasis on flanking manouvres and seizing the initiative were deemed important. And as paradoxical it may sound, the legacy of the German-trained Jaeger officers ensured that tactical attack became the most favoured fighting style.

While this may seem to be a suicidal tactic for a nation of 3.5 million people bordering a superpower that was known to possess substantially more trained reserves than the total population of Finland, since the most expected scenario was that the enemy would launch a surprise attack, the ability to tactically harass and delay the advancing foe was deemed important. It was generally agreed that WWI-style attritional trench warfare was a situation that should be avoided at all costs, since it was precisely the type of combat where the potential opponent excelled and was able to use its material superiority to the fullest extend. Instead, the planners believed that bold attacks at the right time and place could lead to success. Delaying actions were planned to be executed in an active manner, whilst any passive defense was to be only temporary and something that had to be resorted to while preparing for an offense elsewhere.

Moving ahead somewhat, the role of the peacetime army was seen to be as a delaying force with the primary mission of buying time for the mobilization of the field army. Furthermore, as the majority of the the almost roadless Eastern Karelian border between Finland and the Soviet Union was considered to be terrain where division- or even regimental-sized formations would be unable to operate due the lack of necessary infrastructure to supply them, the defense of the borderzone north from the shores of Lake Laatokka (Ladoga) to the Arctic Sea became the task of 25 lightly armed and equipped Independent Battalions (Erillinen Pataljoona). In the event of a war, these units were to be sent into Soviet territory to conduct guerrilla warfare in Eastern Karelia, thus forcing the Red Army to divert men and material away from the Karelian Isthmus (which was always seems as the axis for the main enemy thrust) in order to defend the Murmansk Railway.

We will look at this in more detail later, but suffice it to say that the experiences of the Heimosodat had a strong influence on the evolving strategy and tactical doctrine of the Finnish Army through the 1920’s and 1930’s.

Sources (if you’re interested):

There is relatively little research about the kinship wars available in English (or in Finnish for that matter): In English (most of these books are peripheral to the Heimosodat but address aspects of primarily British involvement)

Return to Table of Contents for “Punainen myrsky – valkoinen kuolema” (Red Storm, White Death)

Next Page

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland