On 20th February 1940, a group of 250 volunteers left London for Finland in order to take part in a war that embodied all the anomalies brought about by the Soviet-Nazi Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. These men were the first of four parties of roughly equal size sent to Finland under the auspices of the Finnish Aid Bureau, a recruitment agency set up with British government sanction at the end of January to assist the Finns in their war with the Soviet Union. The rationale for this expedition, as expounded in War Cabinet meetings in the first weeks of 1940, tells us much about the problems that confronted British decision-makers in this period known as the “Phoney War”, not least the perplexing question of how to best manage the relationship with the Soviet Union given their alliance with Nazi Germany. The volunteers themselves provide a rare and interesting example of a large and organized group of British citizens volunteering for a foreign war with an explicit government imprimatur.

The Russo-Finnish War, what now generally call the Winter War, began with a broad Soviet attack along the Finnish frontier on 30 November 1939. This had been preceded by weeks of fruitless negotiations as the Soviets sought a number of territorial concessions to ostensibly protect the Gulf of Finland, safeguard Leningrad and secure Murmansk. The attack on Finland by the USSR generated a great deal of animosity towards the USSR world-wide, even among many (but we must admit, not all) of those who had been blind to the true nature of that totalitarian regime. By mid-March 1940, a further three contingents had left London at roughly one week intervals and were at Lapua, the mustering point for international volunteers in the south-west of Finland, where they were formed up into a single Battalion, the “Atholl Highlanders,” and where they had begun an intensive period of Maavoimat training that would last for some six weeks.

The Atholl Highlanders had their origins in a Cabinet meeting on 4 January, 1940, where the Lord Privy Seal Sir Samuel Hoare raised the possibility of sending volunteers to Finland. Sir Samuel’s comments were a new departure. “Italy and Germany had shown in Spain how the technique of non-intervention could be exploited as a serious military operation”, the minutes of that meeting record. “[Sir Samuel] suggested we should examine the possibility of giving assistance on the Spanish precedent, but with the difference that personnel sent to Finland should be true volunteers, even if recruited from the serving ranks of the Regular Forces”. This invocation of the ‘Spanish precedent’ is significant, and a studiedly anodyne tone does not conceal the sophistry at work. The reference to the ‘technique of non-intervention’ encapsulates just how little regard the major powers had for reputed agreements of the international community, League-inspired or otherwise. The blatant foreign interference in the Spanish Civil War had made such agreements contemptible and now, far from being a standard of conduct, non-intervention was a ‘technique’, a tool to be wielded for advantage.

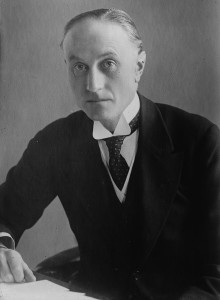

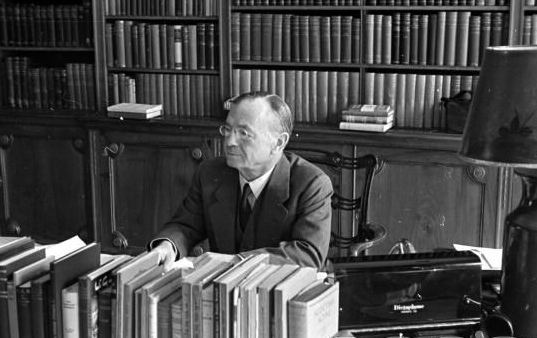

Sir Samuel Hoare, was a senior British Conservative politician who served in various Cabinet posts in the Conservative and National governments of the 1920s and 1930s. He was Secretary of State for Air during most of the 1920s and briefly again in 1940. He is perhaps most famous for serving as Foreign Secretary in 1935, when he authored the Hoare–Laval Pact with French Prime Minister Pierre Laval. In 1936 he became First Lord of the Admiralty, then served as Home Secretary from 1937 to 1939 and was British ambassador to Spain from 1940 to 1944

But for the War Cabinet there were broader concerns. The strategic conundrum of the moment was how to take advantage of the USSR’s attack on Finland: Britain could not be sure into whose arms the Scandinavians were going to jump, if they jumped at all. To this end the War Cabinet was considering pre-emptive action in Norway and Sweden to secure British interests, and deliberations on this point occurred almost concurrently with those concerning the recruitment of volunteers for Finland. Indeed, they intersected in the grander of two schemes to neutralise Scandinavia. In one more modest version of the plan, for which Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty was a vociferous if occasionally blinkered advocate, the Navy would move to block access to the Norwegian port of Narvik, and so stem the flow of Swedish iron-ore to Germany. Norwegian waters would be mined, Norwegian shipping chartered, and neutral shipping controlled by charter or convoy. A second, more ambitious plan involved sending an expeditionary force to Finland on the pretext of helping the Finns, but with the ultimate object of occupying the iron ore fields at Kiruna and Gällivare. The British War Cabinet, then, was in no way averse to intervention – it was more a question of what form intervention would take and what advantage Britain could gain in the war against Nazi Germany. Finland itself was incidental.

The War Cabinet agreed in principle with Sir Samuel’s suggestion but despite the strategic situation and the favourable tenor of public opinion, weeks of prevarication followed. To start with, there was no broad agreement on the shape or character of the pondered contingent. When Sir Samuel first raised the question of volunteers, both he and Chamberlain had stressed the need for a clear policy on just who could volunteer. Was the contingent to be comprised of civilians or current members of the armed forces or both? There were concerns that individuals with any connection to the armed forces – reservists, for example – would come ‘dangerously close’ to breaching Britain’s purported non-intervention. Though he supported the dispatch of “small bodies of experts”, the Secretary of State for War, Leslie Hore-Belisha, was ‘reluctant’ to see volunteers recruited on a ‘considerable scale’. The Secretary of State for Air, Kingsley Wood, felt it necessary that Norway and Sweden agree to the passage of volunteers through their territory although the Finns had already advised that volunteers could be shipped through Lyngenfjiord or Petsamo and advised that Norway had already agreed to the discreet use of Lyngenfjiord.

There was also unease about the quality of individuals to be sent; an issue already hinted at when the Chief of Air Service reviewed a list of individuals who had applied to join the Finnish Air Force. The Air Chief had reported to the Finns that one of these men, alarmingly, “had been in closest contact with the Russian Air Attaché”, and a number of other applicants “were of very doubtful quality, who were likely to do no good to the Finnish cause, and in addition bring nothing but discredit upon this country”. Even if it was not baldly stated, this air of irresolution confirmed that the volunteers for Finland would represent little more than a token gesture of solidarity and a move to assuage the strong public demand for visible support for Finland that was being expressed both in the Press and to MP’s and Cabinet Ministers. Indeed, minutes from a meeting on 12 January 1940 speak of the “good moral effect” of British volunteers regardless of their number, and the desirability of sending a “token force”. This was scarcely the language of military success and in fact completely at odds with the situation in Finland and the desires of the Finnish military command, who were asking for a force of a similar size to the Polish contingent (or even only the equivalent in size of the Spanish, Hungarian or Italian units that were either in Finland or on their way – each the equivalent of a single Division).

Brigadier Christopher G. Ling (1880-1953), a career military officer who had served in the First World War, who was a former Head of the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich and who was also former Director of Military Operations in India was the British General Staff Officer sent to assess the Finns’ military position. Ling reported to the War Cabinet that the Finns spoke of needing up to 30,000 volunteers to hold the country, and that the Finnish Commander-in-Chief Marshal Mannerheim expressed the hope that any British volunteers, whilst “ostensibly” private individuals acting on their own initiative, would actually be members of the British armed forces. Ling himself thought it pointless to send volunteers, as they would be unaccustomed to the extremes of the Finnish winter and untrained in winter warfare, and so would prove more of a hindrance than an asset. The Military Co-ordination Committee did in fact discuss Mannerheim’s request for a large body of men to be ready at the start of the northern summer, though these discussions should be seen in light of the continuing deliberations over a Scandinavian expedition. It was reasoned that such a large force could not be raised unofficially: it would have to be a ‘properly organised expedition, even though this might involve general hostilities with Russia’. The General Staff was asked to draw up “a complete scheme for effective intervention in Finland, bearing in mind other British concerns in the region”, namely the uncertainty over Swedish sympathies and the fate of Swedish iron ore. This all took place in mid-January 1940.

In the meantime, public opinion in Britain was beginning to roil. Demands for action in the Press became more vocal and more persistent. The dispatch of small numbers of aircraft did nothing to relieve the pressure and meanwhile, the War Cabinet continued to discuss various ways of incorporating military action in support of Finland with wider plans for intervention in Scandinavia. There were constant hindrances: it was reasoned that Britain had to be formally asked for help by the Finns – something that the Finns refused to do. As the Finnish Government consistently advised the British Government, the same agreements and methods of transit which had permitted Spanish, Hungarian and Polish Divisions to arrive in Finland could be used to ensure the safe arrival of British units in Divisional strength. However, for ulterior reasons (the reasons for which we have seen and of which Finnish Intelligence was well aware) the British continued to ask for unfettered and unconditional passage through Norwegian and Swedish territory. Notes prepared for the meeting of the Supreme War Council to take place in early February are very clear: :British War Cabinet [is] very sympathetic with the idea of aid to Finland and of intervention in Scandinavia”. However, political considerations and public expectations meant that Britain HAD to do something.

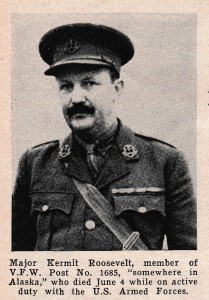

On the 12th of February 1940, with news of major Finnish defensive victories over the Red Army on the Karelian Isthmus filling the front pages of the Press, the British War Cabinet made what was to be a momentous decision with far-reaching consequences. Brigadier Ling was to lead an Allied Military Mission to Finland, for the purposes of arranging the ongoing supply of military equipment from France and Britain to Finland. In parallel, Lt-Col. Colin Gubbins was summoned from Paris, where he was head of a military mission to the Czech and Polish forces under French command and was assigned the task of raising and organizing a single Battalion of volunteers, selecting and appointing a CO and officers and dispatching the Battalion to Finland.

Lt-Col. Colin McVean Gubbins: Gubbins (b. Tokyo, Japan on July 2nd, 1896 – d. Stornoway, UK, 11 Feb 1976) was the younger son and third child of John Harington Gubbins (1852–1929), Oriental Secretary at the British Legation. He was educated at Cheltenham College and at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He was commissioned into the Royal Field Artillery in 1914 and served as a battery officer on the Western Front, where he was wounded, and was awarded the Military Cross. In 1919 he joined the staff of General Sir Edmund Ironside in the North Russia Campaign. His experiences in the Russian Civil War and his subsequent experience during the Anglo-Irish War stimulated his lifelong interest in irregular warfare. After a period with signals intelligence at GHQ India, Gubbins graduated from the Staff College at Quetta in 1928, and in 1931 was appointed GSO3 in the Russian section of the War Office. Having been promoted to Brevet Major, in 1935 he joined MT1, the policy making branch of the military training directorate.

In October 1938, in the aftermath of the Munich Agreement, he was sent to the Sudetenland as a military member of the International Commission. Promoted to Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel, he joined G(R) — later to become MI(R) — in April 1939, where he prepared training manuals on irregular warfare, which were later translated and dropped into occupied Europe. He also made a visit to Warsaw to discuss sabotage and subversion with the Polish General Staff. When British forces were mobilized in August 1939, Gubbins was appointed Chief of Staff to the military mission to Poland led by Adrian Carton de Wiart. He was among the first to report on the effectiveness of the German Panzer tactics. In October 1939, following his return to Britain, Gubbins was sent to Paris as the head of a military mission to the Czech and Polish forces under French command. Gubbins was summoned from France in February 1940 to raise a Volunteer Battalion (the Atholl Highlanders) to serve in Finland, immediately following this he was tasked with raising a further Army Battalion (the 5th Battalion, Scots Guards, Special Reserve) to also fight in Finland. He would then be responsible for the creating of the “Independent Companies” — forerunners of the British Commandos — which he would command in the Norwegian Campaign (April 9 – June 10, 1940). Although criticized in some quarters for having asked too much of untried troops, he showed himself to be a bold and resourceful commander, and was awarded the DSO.

This is the first biography of a man who was destined to live his life in the shadows. A biography of General Colin Gubbins, who was in charge of SOE during World War II.

In November 1940 Gubbins became acting Brigadier and, at the request of Hugh Dalton, minister of Economic Warfare, was seconded to the Special Operations Executive (SOE), which had recently been established to “coordinate all action by way of sabotage and subversion against the enemy overseas”. Besides maintaining his existing connections with the Poles and Czechs, Gubbins was given three tasks: to set up training facilities; to devise operating procedures acceptable to the Admiralty and Air Ministry; and to establish close working relations with the Joint Planning Staff. Despite many frustrations and disappointments, mainly due to shortage of aircraft, he persevered with training organizers and dispatching them into the field. The first liaison flight to Poland took place in February 1941, and during 1942 and 1943 European resistance movements aided by SOE scored notable successes, including a raid on a heavy water production plant in Norway. In September 1943 Gubbins was appointed as head of SOE where he co-ordinated the activities of resistance movements worldwide. It involved consultation at the highest level with the Foreign Office, the Chiefs of Staff, representatives of the resistance organizations, governments-in-exile, and other Allied agencies including particularly the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and from mid-1943 on, the Finnish Security Intelligence Service (Suojelupoliisi, usually abbreviated as SUPO, in Swedish: Skyddspolisen). It turned out that the organized resistance was more effective than Whitehall had expected; in northwest Europe, where SOE’s activities were under Gubbins’s personal control, General Dwight D. Eisenhower later estimated that the contribution of the French Resistance alone had been worth six divisions while in Poland the Polish Home Army had 400,000 members.

In an interesting footnote to the involvement of Colin Gubbins and the 2 British Volunteer Battalions in the Winter War in Finland, it was Gubbins and some of the men from these two Battalions who would be instrumental in the creation of all the now well-known British Special Forces units of WW2. Colin Gubbins was the leader of several secret organisations. He signed his orders “M” — he could not use “C” as this had been taken by the leader of the British SIS and “G” was in common use by the British Army. Gubbins was a Scot from the Western Isles and his middle name was Mcveigh so he used “M”, which was copied by Ian Fleming (Peter Fleming’s brother) for the head man in the James Bond books. In another interesting footnote, the 5th Battalion Scots Guards led assistant adjutant was the veteran Polar explorer Martin Lindsay. Lindsay would much later marry Loelia Ponsonby (after whom Ian Fleming named James Bonds delectable secretary) and one of the colour sergeants in the 5th would in time lead Ian Flemings Commandoes (30 Assault Unit). He was a stocky fair haired explorer called Quintin Riley, who had been with Lindsay on the British Arctic Air Route expedition of 1930-1 and been the meterologoist on the British Graham Land Expedition to Antarctica of 1933-7 (A British Army regular NCO was puzzled by Rileys Polar Meda with Antarctic Clasp – How can you get a medal for playing Polo? he asked).

Ian Fleming’s 30 Assault Unit – a small and very specialized Naval special forces units of WW2

Officers and NCO’s from the special units Colin Gubbins created – the Atholl Highlanders, 5th Battalion Scots Guards, the Independent Companies and the GHQ Auxilary Units – would go on to found and lead the British Commandoes, the Special Air Service (SAS), the Special Boat Squadron in the Mediterranean, the Chindits (Burma) and the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) as well as smaller and even more specialized units such as Ian Fleming’s 30 Assault Unit. Even the OSS had its early active service origins in these units – after Norway, Gubbins was directed by General Headquarters Home Forces to form the Auxiliary Units, a civilian force to operate behind German lines if Britain were invaded and a special training school was established with its Headquarters at Arisaig House (“the Big House”) in Scotland. The Commandos started their life there before they were transferred to the Training School at Achnacarry and all modern close quarter combat and guerrilla warfare tactics and methods stem from the training that was laid down here. It was actually Bill Stirling’s idea to start the Irregular Warfare Training Centre to train guerrilla leaders. Lord Lovat requisitioned the whole area from Fort William to Mallaig. Gubbins got on to General Ironside, the GOC in C Home Forces and the formation of the Irregular Warfare Training Centre was authorised on 2nd June 1940.

The first courses were about 30 strong and consisted of Officers and Sergeants. They lasted three weeks and anybody who didn’t come up to scratch was returned to unit immediately. Later, the school also ran a 30 day course for assault troops which was a precursor to the Battle Schools that were formed later in the war. David Stirling (who eventually formed the SAS) and Fitzroy MacLean, who joined David in the SAS and then went to Yugoslavia to help Tito in the Balkans, both attended the first course. MacLean attended the course in plain clothes (because he was not yet in the Army, he was still in the Foreign Office). What were the courses like? First of all the staff and the instructors. The Commanding Officer was Bryan Mayfield of the Scots Guards, the Chief Instructor was Bill Stirling of the Scots Guards, the Assistant Chief Instructor was Freddie Spencer Chapman of the Seaforths (Chapman was a note pre-WW2 climber and Polar explorer and would go on to fight a lone guerilla war alongside Chinese guerilla’s in Malaya for two years after the Japanese overran Singapore). Fieldcraft was taught by ‘Shimi’ Lovat of the Scots Guards and by NCO’s and men of the Lovat Scouts. Lord Lovat ended up commanding the Commando Brigade. The Assistant Fieldcraft instructor was Peter Kemp (who had fought as a volunteer for the Nationalist in Spain) and would later be David Stirling of the Scots Guards.

Bill and David Stirling were also cousins of ‘Shimi’ Lovat. Demolition training was carried out by Mike Calvert of the Royal Engineers, who started off (again under Gubbins) the British Resistance Organisation and made a real name for himself in the Chindit campaign. Jim Gavin, an Everest climber, assisted him. Two of the key figures at Inverailort were ‘Dan’ Fairbairn and ‘Bill’ Sykes, they were both ex Superintendents in the Shanghai Police and their speciality was close quarter combat, silent killing and dirty tricks and the Fairbairn-design fighting knife became a standard weapon of the Commandoes. Captain P A Walbridge and Cyril Mackworth Praed were both weapons instructors. Also present were arctic explorers Andrew Croft, Jimmy Scott and the veteran explorer George Murrat Levick who had been on the Scott Polar expedition. The climber Sandy Wedderburn taught climbing techniques. The RSM was John Royle who had served with the Highland Light Infantry with David Niven before the War in India. David Niven attended a course (he mentions this in his book “The Moon’s a Balloon’ on page 220) – “They taught us dozens of different ways of killing people without making a noise.” He completed the course before joining the ‘Phantoms.’

The original M/E* of the Special Training Centre consisted of 203 personnel who could cater for the training of approximately 100 officer and 500 other ranks at any one time. There were 55 instructors on establishment – including some civilians who had special experience (mainly some Highland ghillies who taught fieldcraft). By late 1940 another 27 instructors and further admin staff had been added which enabled training at any one time of up to 150 officer and 2,500 other ranks. The Lovat Scouts were very prominent in the ranks of the training establishment. They carried out demonstrations, gave instruction and generally supervised the training. Others joined as instructors — Martin Lindsay from the Gordons (who had also been the Adjutant in the 5th Battalion Scots Guards in Finland and who was also a Polar Explorer). Peter Fleming, Ian’s brother, was there as an Instructor. Gavin Maxwell (author of the book “Ring of Bright Water”), who was a crack shot, also was an Instructor there before moving on to SOE. One of Maxwell’s party tricks was to throw a weighted cigarette packet in the air and shoot it with a revolver before it hit the ground.

Camp X – the first secret agent training camp ever to be built in North America

Even the CIA had its early origins here – that came about on 6th September 1941 when ‘Camp X’ was formed in Canada. The two chaps concerned, ‘Big’ Bill Donovan, a rich American Industrialist who had formed an organisation called the OSS (the Office of Strategic Studies) to see what America could do in secret warfare, and a wealthy Canadian businessman, ‘Little’ Bill Stephenson, formed ‘Camp X.’ Fairbairn went there from “the Big House” to teach them dirty tricks to the Canadians and Americans while Sykes stayed behind to help SOE. He was the man who trained the Czechs who assassinated Reinhard Heydrich and he also assisted in the training of the Norwegian team who destroyed the heavy water plant in Norway.

The relevance of all the above of course is in relation to the service of the Atholl Highlanders and the 5th Battalion Scots Guards (Special Reserve) in Finland over the course of the Winter War. At the start of WW2, the British had no units of the type that we now call Special Forces – while the Germans had trained for some time in the kind of specialist warfare the British were just beginning to learn. And the Maavoimat had been planning, experimenting and training for years in this type of warfare in preparation for a possible conflict with the USSR. Both the British Volunteer Battalions largely consisted of the sort of men who were drawn towards special forces operations – and with the Maavoimats experience in such matters, as these men went through an abbreviated Finnish combat training school, this was recognised. Although the immediate need was for troops on the battlefront, the Maavoimat assigned a small number of experienced instructors to the two Battalions and continued their training while they manned rear line positions on the Karelian Isthmus. After the last winter offensives of the Red Army were defeated, the two British Battalions were absorbed into the Finnish Osasto Nyrkki (Fist Force) unit. This was the elite of the elite Maavoimat units, tasked with aggressive “behind-the-lines” missions focusing on strategically important targets. It was a mission that men such as Orde Wingate, “Shimi” Lovat, Mike Calvert and David Stirling would take to like Tigers to a raw steak – and the training and subsequent combat they experienced in Finland would have a major flow-on effect in the creation of similar special forces units in the UK and subsequently in the US. In this, the British would benefit from the many years that the Maavoimat had put in to developing such units.

In 1933, following the initial reorganization of the Maavoimat into Combined Arms Regimental Battle Groups loosely aligned within a largely administrative Divisional structure, Marshal Mannerheim and the Military High Command had made a decision to establish a small number of “elite” or specialized units, units which were to be completely separate and clearly differentiated from the existing Jaeger Regiments, who were primarily elite Infantry units. Following a series of planning sessions, the decision was made to establish these “elite” units over late 1933 and 1934. A later Post in a series on the Maavoimat will provide an initial summary of the formation of these units followed by a more detailed look at each Unit in turn. However, in order to better understand the training that the men of the two British Volunteer Battalions received we should first take a quick look at the early origins and formation of the Maavoimat’s Osasto Nyrkki (Fist Force).

“If your enemy is ….. taking his ease, give him no rest. If his forces are united, separate them. If sovereign and subject are in accord, put division between them. Attack him where he is unprepared, appear where you are not expected.” Sun Tzu

Hauptmann Dr. Theodor von Hippel (born 19 January 1890 in Toruń, date of death unknown) was the German army and intelligence officer responsible for the formation and training of the Brandenburgers commando unit. in WW1 he served under General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck in the East African theatre, where Lettow-Vorbeck had conducted a brilliant guerrilla campaign against Allied colonial troops. Shortly before WW2, Inspired by the example of Lettow-Vorbeck, von Hippel proposed that small, élite units, highly trained in infiltration and sabotage and fluent in foreign languages, could operate behind enemy lines, wreaking havoc on the enemy’s command, communication and logistical chains. The unit continued to grow from a single regiment into one of the most feared and effective divisions fielded by Germany in World War II, participating on every front and in nearly every important campaign.

Osasto Nyrkki originated in 1931 with a Colonel Jussi Härkönen who, while unofficially (he was on leave at the time) attending training in Germany with the Heer, encountered one Hauptmann (Captain) Theodor von Hippel, an officer who had served under General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, Commander of the German East African Forces in World War I. Von Hippel regaled Colonel Härkönen with tales of the brilliant guerilla war Lettow-Vorbeck had waged against the British in East Africa – as well as comparisons with the successes enjoyed by the British T E Lawrence and the Arabs, who used similar hit-and-run tactics against the Turks. Hauptmann von Hippel was a strong advocate of the tactics pioneered by his former commander and the British Lawrence and forcefully advocated the benefits and advantages of such a force. Indeed, he completely convinced Colonel Härkönen of the military possibilities inherent in a small elite unit trained to operate behind enemy lines. Colonel Härkönen took these thoughts with him on his return to Finland and, in 1933, as the Finnish military reorganisation kicked into high gear, he made a case directly to Marshal Mannerheim for the formation of such a unit within the Armed Forces.

Härkönen’s proposal was for a small, élite unit, highly trained in sabotage and fluent in foreign languages, particularly Russian, which could operate behind enemy lines and wreak havoc with the enemy’s command, communication and logistical tails. Mannerheim saw the possibilities inherent in such a unit and, over the opposition of some senior officers within Defence Headquarters, whom he overruled, gave Colonel Härkönen the necessary authority and budget to make his vision a reality. Colonel Härkönen reported directly to Marshal Mannerheim and was given a free hand, with the provisio that the Marshal wanted to see results. With the unit formally established from 1 January 1934, Colonel Härkönen got down to work, with one of his first successes being the recruiting of half a dozen German veterans of Lettow-Vorbeck’s force together with another half dozen British officers and NCO’s who had fought with the Arab’s against the Turks under T E Lawrence. Together with a dozen Finnish officers and NCO’s whom Härkönen personally recruited into the unit, it was an unusual start to the formation of a new unit.

The German and British NCO’s and Officers recruited were professionals who, putting aside the historical differences between their respective countries, worked closely with their Finnish colleagues to establish the organisation, objectives and training for the new unit. Recruiting started in May 1934 with small numbers of volunteers. From the start, the training regime was innovative and physically demanding, far in advance of normal Maavoimat training which was already becoming tougher, with a rapidly growing emphasis on combat skills and small unit tactics over square bashing. Osasto Nyrkki training instructors staff were all hand picked, with the ability to outperform any of the volunteers. Exercises were conducted using live ammunition and explosives to make training as realistic as possible. Physical fitness was a prerequisite with speed and endurance marches conducted through the hills and forests and over assault courses, all while carrying arms and full equipment. Training continued by day and night with river crossings, climbing, weapons training, unarmed combat, map reading, and small boat operations. Living conditions were primitive in the camp, with trainees housed under canvas in tents or in shelters they constructed for themselves.

Finland was also one of the very few countries in the world in the 1930’s whose Army encouraged the learning of unarmed and armed martial arts combat techniques. From the early 1930’s on, a synthesis of techniques from Savate, Judo, Ju-Jitsu and Karate together with knife and bayonet fighting techniques were taught within the Armed Forces. Osasto Nyrkki volunteers got an advanced course in full measure. The unit also stressed marksmanship, close quarter battle skills, mental agility, orienteering, camouflage and the learning of colloquial Russian. Soldiers were taught to function as individuals as well as small units, to use their initiative, to be aggressive at all times and to never give up. And right from the very first, during training, officers and men collaborated in the development of the units military doctrine and techniques specifically adapted to the units objectives. In this, Osasto Nyrkki was by, virtue of the training and skills passed on to the British Volunteers, the real predecessor of all of today’s special forces units such as the SAS. Men such as David Stirling, “Shimi” Lovat, Earl Jellicoe, F. Spencer Chapman, Mike Calvert and Orde Wingate would be renowned throughout the English-speaking world for their exploits, but they would always be the students of the real masters, Osasto Nyrkki.

The Finnish Aid Bureau and Harold Gibson

The League resolution also seems to have resonated with an “employee” of the Cabinet Secretariat called Harold Gibson. In an article by one Elizabeth Roberts entitled “The Spanish Precedent: British Volunteers in the Russo-Finnish Winter War” the author comments “The League resolution also seems to have resonated with an employee of the Cabinet Secretariat called Harold Gibson – though whether it prompted his conscience or his ambition is an open question. This enigmatic figure – who had somewhat fantastically worked for the International Board for Non-Intervention during the Spanish Civil War – now lobbied for the creation of a British volunteer contingent to intervene in Finland, suggesting it to Halifax at about the same time it was first raised in Cabinet. Gibson was soon to play the leading role in the Finnish expedition.” When the Finnish Aid Bureau was setup and held its first meeting. Harold Gibson was appointed the Director, and he and fourteen other men comprised the management committee. This management committee included Conservative MP and staunch anti-communist Leo Amery as well as the Finnish Ambassador, Gripenberg, together with a series of aristocratic patrons, including Lord Davies and Lord Phillimore (the erstwhile head of the Finnish Fund) and the Conservative MP and future Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. In theory the Finnish Aid Bureau existed both to raise money and to recruit men to fight for Finland, and in accordance with the government’s stipulations this work was to be done without visible connivance. In practice, the Bureau was more or less a front organisation for the British Government.

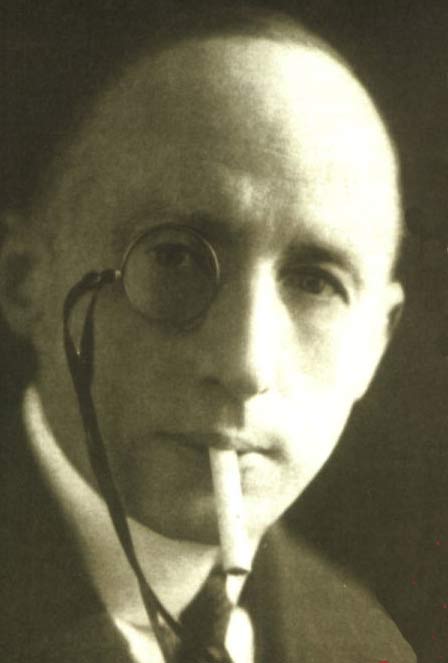

Harold Charles Lehr Gibson (1885/87-1960): Gibson was a senior member of the SIS and was Head of Station in various eastern european countries from 1919 on. On 12.6.1947, Harold Gibson, “attached to a department of the Foreign Office”, is gazetted a Companion of the Order of the St Michael and St George. He was awarded the US Legion of Merit – this was gazetted in The London Gazette of 23.7.1948, when he was listed as a temporary Major, Army N° 115076. His first wife was one Rachel Kalmanoviecz (died 1947), after which he married Ekaterina Alfimov. His younger brother Archibald, a journalist with “The Times”, was Head of Station in Bucharest towards the end of WW2. Gibson retired in 1958 as a Major, albeit an Acting Major and was found shot dead on 24 August 1960 at 25 Via Antonio Bosio, Rome. The official reason was suicide due to “money problems”.

The Director of the Finnish Aid Bureau, Harold Gibson, rather than being an “employee of the Cabinet Secretariat”, was actually a long-time and quite senior member of the British Security Intelligence Service (SIS – otherwise known as MI6) and was responsible for running a network of undercover British agents working inside the Soviet Union both in the inter-war years and during and after WW2. Once his cover was blow by a disgruntled Russian operative in 1945, Gibson was under close surveillance by Soviet intelligence until his death in 1960. In the inter-war years and during WW2, Gibson was also heavily involved in British dealings with the Zionist movement. Harold Gibson was born in either 1885 or 1887 (sources differ) and was Head of Station for the SIS in Constantinople from 1919-21 (military rank of Major), Head of Station in Bucharest (1922-30), Head of Station in Riga (1930-33), Head of Station in Prague (1933-40: he was still there when the Germans marched in on 15 March 1939. Gibson and his staff decamped to London on 30 March 1939), Head of Station in Istanbul from 1941 through WW2, Head of Station in Prague (1945-48), Head of Station in Berlin (1949-50) and finally Head of Station in Rome from 1955. In other words, from 1919 on he was a fairly senior officer with the British Security Intelligence Service and intimately involved with both the USSR and the Zionists.

Archibald Gibson was “The Times” correspondent in Rumania from 1928 until 1940. After a further six years in South Eastern Europe and the Middle East as a journalist, he settled in London and drafted a book about Rumania over the years 1935 to 1945, based partly on his dispatches for “The Times”. Archibald McEvoy Gibson was born in Moscow on 3 March 1904 if Anglo-American parentage. His mother, Dagmar Gibson nee Lehers, was an American by borth: his father, Charles John Gibson Jnr, was assistant manager of the Moscow Depot of the Nevsky Stearin soap and candle company, founded by Archie’s great-grandfather James. The Gibson’s were forced by the revolution in Russia to leave the country and in late October 1917 the fanily reached Britain and settled in Surbiton. Both Harold and Archie were fluent speakers of Russian and cultivated the friendship of Russian refugees, who provided information about events in the Soviet Union.

As SIS Station Chief in Prague, Harold Gibson was involved with the Enigma machine. MI6 knew very little about this German cipher machine “…until Major Harold Lehr Gibson, the MI-6 resident at Prague, reported that the Polish secret intelligence service, which worked with MI-6 against the Russians and the Germans, was also interested in Enigma. Department BS4, the cryptographic section of the Polish General Staff, had legally acquired the commercial version of Enigma; and Polish cryptanalysts had managed to resolve some of the mathematical problems involved in deciphering its transmissions. But the Polish penetration of Enigma was not mechanical; and they had experimented only with the commercial model, which, it could be assumed, the Germans had modified and refined for the Wehrmacht’s use.” In June of 1938, Gibson in Prague reported that he had just returned from Warsaw where, through the Polish intelligence service, he had encountered a Polish Jew who had offered to sell MI-6 his knowledge of Enigma. The Pole, Richard Lewinski (not his real name), had worked as a mathematician and engineer at the factory in Berlin where Enigma was produced. But he had been expelled from Germany because of his religion. At the interview with Gibson, Lewinski announced his price: 10,000 Pounds, a British passport, and a resident’s permit for France for himself and his wife. Lewinski claimed he knew enough about Enigma to build a replica, and to draw diagrams of the heart of the machine — the complicated wiring system in each of its rotors.

MI6 decided to send two experts to Warsaw to interview Lewinski in person. One was Alfred Dilwyn Knox, England’s leading cryptanalyst. [The other] was Alan Mathison Turing, a young man with a reputation as an outstanding mathematical logician. Briefing the men on their mission, Menzies said their task was to go to Warsaw, interview Lewinski and report upon his knowledge. If they were satisfied that it was genuine, they were to arrange with Gibson to take the Pole and his wife to Paris and place him in the charge of Commander Wilfred Dunderdale, the MI-6 resident there, known to the service as “2400.” Then, under their supervision, Lewinski was to re-create the Enigma machine. [T]he two men who journeyed to Warsaw to discover how much Richard Lewinski knew about Enigma and after it was clear that Lewinski’s knowledge of these questions was considerable they recommended that his bargain be accepted. The necessary arrangements were made, and Lewinski and his wife were taken by Major Gibson and two other men to Paris, traveling on British diplomatic laissez-passez through Gdynia and Stockholm to avoid Germany.

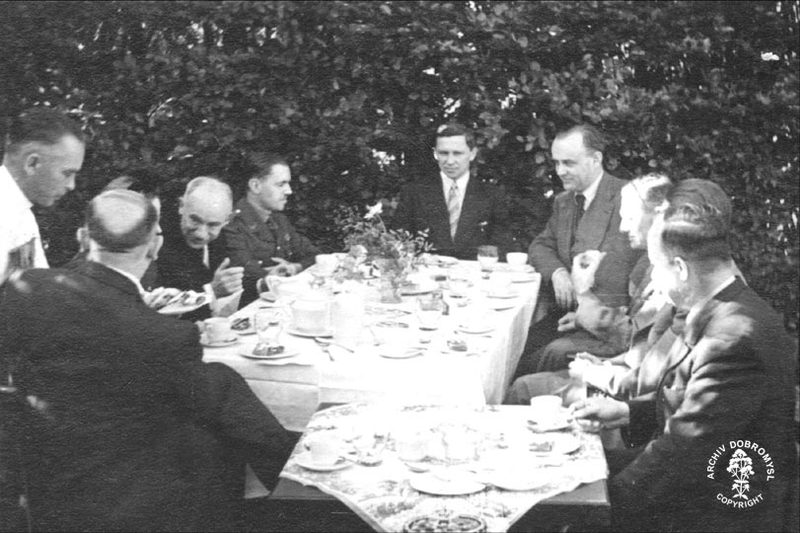

President Beneš meeting with British Intelligence officers. Seated to the left of Eduard Beneš are Harold Gibson, a British SIS officer, Emil Strankmüller and František Moravec.

Gibson was also instrumental in whisking the Czechoslovakian Intelligence Service out of Czechoslovakia on the eve of WW2. The background to this operation goes back to 1938 when the British Prime Minister came back from the Munich Conference with an agreement from Adolf Hitler that in return for being given the Sudetenland borderlands of Czechoslovakia, he had made his last territorial claim in Europe, and would respect the independence of Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak President, Dr Edvard Beneš, was not invited to the conference and resigned after being forced to acquiesce to the loss of territory. Six months later Hitler disregarded his promises, supported the establishment of a fascist regime in Slovakia, and invaded the Czech provinces of Bohemia and Moravia. On the eve of invasion, in March 1939, the Czechoslovak intelligence services were whisked from Prague and settled in Rosendale Road, West Dulwich, where they set up the first military radio station in England, which initially established contact with the home resistance. Gibson was the organiser of this move.

Czechoslovak military intelligence staff group: Left to right: Col Frantisek Moravec, Captain Jaroslav Tauer, Major Harold Gibson, Captain Alois Caslavka, President Benes, Prokop Drtina, Jaromir Smutny (Gibson is third from the left – Photograph courtesy of the family of Jaroslav Bublik)

During the Second World War the Czechoslovak military intelligence services ran independent radio stations from England. At the time they were secret, and today there is practically nothing left of them, and there are very few people left who know anything about them. People can be forgiven for not knowing that they were ever there, but they played an important role in supplying intelligence information to the Allies, and in maintaining contact with the Czechoslovak resistance. Each station was called in Czech “Vojenská Radiová ústředna” (military radio centre) known by its initial letters as the VRÚ.

Post WW2, Gibson is also remembered for what would become known as the Bogomolets Affair. Viktor Bogomolets was Russian who came from an aristocratic Russian family. He had fought against the communists during Russia’s 1917 civil war. Col. Harold Gibson met Bogomolets in Istanbul in 1920 and immediately hired him to work for MI6. The two men roamed around Europe, with Bogomolets swiftly assembling his own network of Russian agents inside the Soviet Communist party. Bogomolets stopped working for MI6 in 1934 when Soviet agents tried to lure him back to Moscow. The agents sent meticulous reports home about Bogomolets’ lavish lifestyle and his Romanian wife’s penchant for expensive haircuts and perfumes. He resumed his spying activities again in 1944, first in Portugal and then Cairo. In 1945, after more than three decades spying for British intelligence, Bogomolets, was curtly informed that he had been stripped of his British citizenship. At this point Bogomolets decided to betray his British masters and he then became one of Moscow’s most accomplished double agents. He passed crucial information back to Moscow about British intelligence at the height of the Cold war. Bogomolets’ reports were circulated among the top echelons of the Soviet Union’s leadership – and were even read by Stalin himself. He betrayed the man who had recruited him to MI6 in the first place, Harold Gibson. Bogomolets then disappears from view as far as the records are concerned. He is believed to have died in Paris.

Identity bracelet dating from approximately 1941 when Harold Gibson was SIS Chief of Station in Istanbul. There is no record of Gibson having been promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel or Colonel and when he retired, his rank was listed as Major. However, the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel may well have been an acting rank during WW2, after which he returned to his substansive rank – pure conjecture of course.

What we do know is that in late 1939 Harold Gibson, ostensibly a Civil Servant but in reality a senior member of MI6, was soon to play a leading role in the Finnish expedition. Almost immediately after assenting to the scheme and instructing Gubbins to proceed the Cabinet had second thoughts. On 26th January, Chamberlain had voiced concerns over the proposed scope of the new ‘Finnish Aid Bureau’. Meanwhile, the Finnish Minister in London, George Gripenberg, had been in contact with the indefatigable and staunchly anti-Communist Conservative MP Leo Amery, who in turn “suggested” a number of prominent individuals for a Committee to assist with fundraising. Chamberlain worried that if it were given such stature the purpose of the Finnish Aid Bureau – or rather the British government’s role in it – would be misconstrued. It must be made absolutely clear to Amery, “who was enthusiastically in favour of assistance to Finland, and [who] no doubt visualised thousands of volunteers being sent from this country”, that the Government had merely authorised the recruitment of British subjects for an international force. Amery needed to be told of the “strong arguments against attempting to organise a British volunteer force on a large scale”, the Minutes note. But the War Cabinet’s concerns and its attempt to dampen enthusiasm for the Finnish cause appears to have had little effect, and as we will see, the Finnish Aid Bureau’s Committee of Management featured a number of distinguished names.

Leo Amery in 1940: Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery (22 November 1873 – 16 September 1955), was a British Conservative Party politician and journalist, noted for his interest in military preparedness, India, and the British Empire.

During the Second Boer War Amery was a correspondent for The Times and in 1901, in his articles on the conduct of the war, he attacked the British commander, Sir Redvers Henry Buller, which contributed to Buller’s sacking. Amery was the only correspondent to visit the Boer forces and was nearly captured with Winston Churchill. He turned down the chance to be editor of The Observer in 1908 and The Times in 1912 in order to concentrate on politics and in May 1911 he was elected unopposed as a Liberal Unionist MP for Birmingham South, a seat he would hold until 1945 (the Liberal Unionists were to fully merge with the Conservatives the following year). During WW1 his language skills led to his employment as an Intelligence Officer in the Balkans and later, as an under-secretary in Lloyd George’s national government, he helped draft the Balfour Declaration (1917). He also encouraged Se’ev Jabotinsky in the formation of the Jewish Legion for the British Army in Palestine and was somewhat of a supporter of Zionism.

Amery was First Lord of the Admiralty (1922–1924) under Andrew Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin and Colonial Secretary in Baldwin’s government from 1924 to 1929. Amery was not invited to join the National Government formed in 1931. He remained in Parliament, but joined the boards of several prominent corporations. This was necessary as he had no independent means and had depleted his savings during WWI and when he was a cabinet minister during the 1920s. Among his directorships were the boards of several German metal fabrication companies (representing British capital invested in the companies), of the British Southern Railway, the Gloucester Wagon Company, Marks and Spencer, the famous shipbuilding firm Cammell Laird, and the Trust and Loan of Canada. He was also chairman of the Iraq Currency Board. In the course of his duties as a director of German metal fabrication companies Amery spent a lot of time in Germany during the 1930s, mostly visiting factories, Amery gained a good understanding of German military potential. Hitler became alarmed at this situation and as a result ordered a halt to non-German directors of German companies. Amery had a lengthy meeting with Hitler on at least one occasion and also met at length with the Czech leader, Benes, the Austrian leaders Dollfuss and Schuschnigg and Benito Mussolini of Italy.

In the debates on the need for an increased effort to rearm British forces, Amery tended to focus on army affairs, with Churchill speaking more about air defence and Roger Keyes talking about naval affairs. While there was no question that Churchill was the most prominent and effective, Amery’s work was not insignificant. He was a driving force behind the creation of the Army League, a pressure group designed to keep the needs of the British Army before the public. In the 1930s, Amery, along with Winston Churchill, was a bitter critic of the appeasement of Nazi Germany, often openly attacking his own party. It is commonly believed that, when Neville Chamberlain announced his flight to Munich to the cheers of the House, Amery was one of only four members who remained seated (the others were Churchill, Anthony Eden and Harold Nicolson). Being a former Colonial and Dominions Secretary, he was very aware of the views of the dominions and strongly opposed giving Germany back her colonies, a proposal seriously considered by Neville Chamberlain. When the war came, Amery was one of the few anti-appeasers who was opposed to co-operation with the Soviet Union in order to defeat Nazi Germany. This came from a life-long fear of Communism.

Amery is famous for two moments of high drama in the House of Commons early in World War II. On 2 September 1939, Neville Chamberlain spoke in a Commons debate and said (in effect) that he was not declaring war on Germany immediately for having invaded Poland. This greatly angered Amery and was felt by many present to be out of touch with the temper of the British people. As Labour Party leader Clement Attlee was absent, Arthur Greenwood stood up in his place and announced that he was speaking for Labour. Amery called out to him across the floor, “Speak for England!”—which carried the undeniable implication that Chamberlain was not. The second incident occurred during the notorious Norway Debate in 1940. After a string of military and naval disasters were announced, Amery famously attacked Chamberlain’s government, quoting Oliver Cromwell: “You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!” Lloyd George afterwards told Amery that in fifty years he had heard few speeches that matched his in sustained power and none with so dramatic a climax. This debate led to 42 Conservative MPs voting against Chamberlain and 36 abstaining, leading to the downfall of the Conservative government and the formation of a national government under Churchill’s premiership. Amery himself noted in his diary that he believed that his speech was one of his best received in the House, and that he had made a difference to the outcome of the debate.

During the war Amery was Secretary of State for India, despite the fact that the fate of India had been a keen issue of dispute between Churchill and Amery for many years. Amery was disappointed not to be given a post in the War Cabinet, but he was determined to do all he could in the position he was offered. He was continually frustrated by Churchill’s intransigence, and in his memoirs records that Churchill knew “as much of the Indian problem as George III did of the American colonies.” In this context, we can see that Leo Amery’s involvement with the Finnish Air Bureau was no mere token – as an influential Conservative Party MP, he carried considerable weight. It is also worth noting that Amery was somewhat of a Zionist .

On the same day as Chamberlain expressed his concerns around aid to Finland, the Finnish Aid Bureau held its first meeting. Harold Gibson was appointed Director, and he and fourteen other men comprised the management committee. This naturally included Leo Amery and Gripenberg, as well as a series of aristocratic patrons, including Lord Davies and Lord Phillimore (the erstwhile head of the Finnish Fund) and the Conservative MP and future Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. Gibson however was firmly in charge. In theory the Bureau existed both to raise money and to recruit men to fight for Finland, and in accordance with the government’s stipulations this work was to be done without visible connivance. But this did not preclude assistance in response to advocacy, so long as the pretence of autonomy was maintained. Consequently references to the Finnish Aid Bureau appear in the War Cabinet minutes very soon after its official establishment as though it were a separate entity separately grown, whose entreaties were to be considered with the usual equanimity. On 2 February for example, the Finnish government informed the Bureau that foreign technicians were desired to free Finnish men for military service. Gibson in due course contacted the Foreign Office, the Home Office and the Ministry of Labour and proposed a recruitment scheme – to which the Ministry of Labour agreed on the 27th of February 1940. Among those who were to be sent to Finland were technicians recruited from refugee camps in Britain (some 1,000 technicians, primarily Polish refugees, were enlisted into the scheme and sent to Finland in late March 1940, where they would fill positions in Finnish industry).

One of the Finnish Aid Bureaus first activities was a trip that some of its leaders made to Finland in February 1940. Churchill was closely, if unofficially involved – attested to by the fact that Harold Macmillan, who went on the trip, was in contact with Churchill even while in Finland. After having met Finnish leaders and sensing their growing confidence in Finland’s ability to hold out against the USSR and the Red Army, Macmillan wrote to Churchill advising him of the situation, demanded “urgent action” in support of Finland and hoped that Churchill would “do your best” to encourage the War Cabinet to provide substantial assistance “otherwise our hopes of using the situation to advantage against Germany may be lost.” The oddest thing about this missive was that Macmillan was writing to a minister who was not in charge of any matters related to Finland and who had no power to make decisions on them. However, Macmillan did know that Churchill was an anti-communist whose interest in the Winter War was on a scale entirely different from that of other ministers in the War Cabinet. He had however assumed correctly that Churchill would put more pressure on the Prime Minister so that more aid would be forthcoming for Finland.

And Churchill had and would play a key role in efforts to assist Finland, albeit as part of the Grand Strategy he envisaged for outflanking Germany in Scandinavia. It had been Churchill who, on 22 December 1939, had led the British War Cabinet into its first detailed discussion on the Winter War. It had been Churchill who had proposed that pressure be applied on Sweden and Norway to encourage them to send armies of volunteers to Finland, and it had been Churchill who had first broached the possibilities of British military assistance. And, aside from any of his other initiatives, it had been Churchill who had robustly supported the sending of British Volunteers to Finland under the aegis of the Atholl Highlanders – it was the sort of scheme that appealed to Churchill’s mindset and he had supported it strongly from the start. Throughout December and January Churchill had continued to put pressure on the War Cabinet, stressing that his sources told him that above anything the Finns needed artillery, ammunition and aircraft with which to fight and that it was imperative to speed up British aid. It was Churchill who had pushed strongly for the British Army to support and equip the ANZAC Battalion and to send it off to Finland accompanied by a significant number of artillery pieces and ammunition. As First Lord of the Admiralty (in charge of the Royal Navy) Churchill also decided to forward to Finland some of the aircraft of his Fleet Air Arm – these were the 33 Blackburn Roc’s that would be flown to Finland. He also proposed that some of the heavy air-defence guns that were then protecting British cities against an expected German air attack be sent to Finland.

Major-General Sir Alfred William Fortescue Knox (30 October 1870 – 9 March 1964) was a career British military officer and later a Conservative Party politician. In 1911 General Knox was appointed the British Military Attaché in Russia, where he served as a spy.[1] Anti-Semitic[citation needed] and a fluent speaker of Russian, he became a liaison officer to the Imperial Russian Army during First World War. He is depicted in the classic book 1914 by Solzhenitsyn as a somewhat troublesome attache as General Samsonov attempts to lead his army through East Prussia. During the October Revolution in Russia he observed the Bolsheviks taking the Winter Palace on 25 October (7 November) 1917. He was elected an MP in 1924 and served until 1945. His parliamentary questions mainly concerned the Soviet Union and the threat of Hitler as well as the rearmament of Britain during the inter-war period.

Volunteers who had passed the initial firearms knowledge, age and health check filling out forms inside the basement of the Finnish Legation on the morning of 17th February 1940.

Prime Minister Chamberlain resisted the creation of any volunteer units but he finally changed his mind in January 1940 after pressure from Churchill and the French Prime Minister together with the ever more strident demands from the British Press. The volunteer contingent was supposedly to be created and supported by the Finnish Aid Bureau and was officially independent but, as we have seen, secretly controlled by the British authorities – a secret that did not remain one for long as pro-Soviet MP’s exposed the facts. After the decision was made to establish the volunteer unit, arrangements began to be made for equipment and funding and again, Churchill’s influence was involved. Churchill arrange for the unit to be equipped by the British Army, while Lord Nuffield (a wealthy industrialist) and Max Beaverbrook, the newspaper publisher, key Conservative strategist and a close friend of Churchill’s, promised to personally pay for the transport expenses of the Volunteers.

As mentioned previously, on the 12th of February 1940 the British War Cabinet had appointed Brigadier Christopher Ling to lead an Allied Military Mission to Finland, for the purposes of arranging the ongoing supply of military equipment from France and Britain to Finland. In parallel, Lt-Col. Colin Gubbins was summoned from Paris, where he was head of a military mission to the Czech and Polish forces under French command and was assigned the task of raising and organizing a single Battalion of volunteers, selecting and appointing a CO and officers and dispatching the Battalion to Finland. Gubbins was advised that in sending volunteers, Britain would have to be cautious about appearing to directly intervene. While active members of the military would be permitted to join, they would have to resign from service – and recruitment would be carried out at arms length under the auspices of the Finnish Legation, making it clear that individuals were being recruited for an international volunteer force and not at the sole behest of Britain.

That this international volunteer force was for the best part fictional was less important than the protection such a designation offered. There was to be no formal connection between the recruitment bureau and the British government, though some unofficial contact would be necessary: the War Cabinet wished to ensure that no man with existing service obligations was recruited (although resignations would be permitted), and that no “undesirable characters” made their way on to the expedition. The British government was also protected in part by a resolution of the League of Nations. In one of its last, desultory acts the League had condemned the Soviet invasion and urged “every member of the League to provide Finland with … material and humanitarian assistance … and to refrain from any such act which might weaken Finland’s powers of resistance”. This League resolution proved to be a vital legitimising device for the British volunteers. The other obstacle were the provisions of the Foreign Enlistment Act – legislation which prevented British subjects from fighting in wars in which Britain was neutral.

A Poster for the Finnish Aid Bureau that was widely seen across the UK in February 1940: Support for Finland was at an all-time high through the period December 1939 to April 1940 and huge queues of would-be volunteers formed outside the Finnish Legation. Had the British Government been willing, many more Volunteers could have been sent than were.

Gubbins was no man for indecision. Neither were Gibson nor Amery for that matter. Gubbins first act was, in company with Gibson and Amery, to meet with Ambassador Gripenberg at the Finnish Legation on the 15th of February to determine what action was to be taken. Immediately after which it was announced to the Press in a joint meeting of the Directors of the Finnish Aid Bureau together with the Finnish Ambassador, Gripenberg, that volunteers at a Recruiting Bureau to be opened at the Legation would be accepted commencing on the 17th of February and that existing members of the military would be accepted but would, if accepted need to resign from the services in order to be sent to Finland. It was expected that the first group of Volunteers would leave within days. The provisions of the Foreign Enlistment Act were circumvented by announcing that all volunteers would be accepted into the Atholl Highlanders Regiment, a legal private army in the private employ of the Duke of Atholl.

The existence of the Atholl Highlanders Regiment as a legal private army was somewhat of an anomaly, but under the circumstances a useful one. Dating back to 1777, the Atholl Highlanders had originally been formed as the 77th Regiment of Foot by the 4th Duke ofAtholl and had spent most of its existence in Ireland. The Regiment was disbanded in 1783. However, 50 years later, in 1839, the 6th Duke, as Lord Glenlyon, resurrected the regiment as a bodyguard which he took to the Eglinton Tournament at Eglinton Castle, Ayrshire. Three years later, in 1842, the regiment escorted Queen Victoria during her tour of Perthshire and in 1844, when the Queen stayed as a guest of the Duke at Blair Castle, the regiment mounted the guard for the entire duration of her stay. In recognition of the service that the regiment provided during her two visits, the Queen announced that she would present the Atholl Highlanders with Colours, thus giving the regiment official status. The regiment’s first stand of Colours was presented by Lady Glenlyon on behalf of the Queen in 1845. Under the 7th Duke, the regiment regularly provided guards for royal visitors to Blair Castle (which was a convenient stopping point on the journey to Balmoral). Following the First World War, parades of the regiment became fewer, although it did provide guards when the Crown Prince of Japan and King Faisal of Iraq visited Blair Castle in 1921 and 1933 respectively. After 1933, there was little activity, and it seemed the regiment would disappear into obscurity until Lt.Col. Gubbins performed is miraculous act of resurrection in February 1940 with the agreement of the John Stewart-Murray, 8th Duke of Atholl.

The link was purely nominal – the Atholl Highlanders Regiment that was sent to Finland was not linked in any way to the ceremonial Regiment in Scotland but it did form a suitable avenue to legally enlist and send volunteers to Finland as an organised unit. And the volunteers flocked to join, perhaps inspired to some degree by the news reports that filled the papers regarding the gallant fight being put up by the Finns and the less frequent news reports from the ANZAC Battalion already in Finland. Whatever the reason, on the morning of 17th February 1940, the queue outside the Finnish Legation was already hundreds of men long and growing by the minute, with the Police being required to ensure order, such was the excitement of the moment. Gubbins had enlisted the aid of a number of experienced NCO’s and Officers from the Coldstream Guards and these were quick to sort the wheat from the chaff, even before medical exams were carried out. Again, no time was to be wasted on training and only fit single men with a good physique and previous experience with firearms were to be accepted. The .303 test (“here’s a stripped down Lee-Enfield .303, reassemble starting NOW!” worked like a charm, as did the more obvious selections based on age (“neither too young or too old”) and apparent health. A mere statement on marital status was accepted.

On the 18th of February Gubbins interviewed a small number of Officers from the British Army in his search for a Commanding Officer. Most of the officers were nonentities, most were unsuitable for various reasons, but one officer stood out above the rest. This officer was Major Orde Wingate, at the time the unhappy commander of the 56th Light Anti-Aircraft Brigade, Royal Artillery, in Britain. Gubbins, Gibson and Amery were all well aware of Wingate for a number of reasons. Gubbins, with his interest in irregular warfare, was well aware of Wingate’s activities in Palestine, where he had made a reputation for himself as the creator, trainer and leader of the Special Night Squads in Palestine. These were small armed assault groups formed of British and Haganah volunteers who were tasked with combating Palestinian Arab guerillas. Wingate had created, trained, commanded and accompanied them on their patrols. The units frequently ambushed Arab saboteurs who attacked oil pipelines of the Iraq Petroleum Company, raiding border villages the attackers had used as bases. Wingate disliked Arabs, once shouting at Hagana fighters after a June 1938 attack on a village on the border between Mandatory Palestine and Lebanon, “I think you are all totally ignorant in your Ramat Yochanan [the training base for the Hagana] since you do not even know the elementary use of bayonets when attacking dirty Arabs.” But the brutal tactics proved effective in quelling the uprising, and Wingate had been awarded the DSO (Distinguished Service Order) in 1938.

Major-General Orde Charles Wingate, DSO and two bars (26 February 1903 – 24 March 1944), was a British Army officer and creator and leader of special military units in Palestine in the 1930s, in Finland in 1940, in Ethiopia in 1941 and Burma from 1942-1944. A highly religious Christian, Wingate became a supporter of Zionism, seeing it as his religious and moral duty to help the Jewish community in Palestine form a Jewish state. Assigned to the British Mandate of Palestine in 1936, he set about training members of the Haganah, the Jewish paramilitary organization, which became the Israel Defense Forces with the establishment in 1948 of the state of Israel. He went on to lead a volunteer Battalion (the Atholl Highlanders) in Finland in the Winter War as well as irregular forces in Ethiopia against the Italians but is most famous for his creation of the Chindits, airborne deep-penetration troops trained to work behind enemy lines in the Far East campaigns against the Japanese during World War II (although recent historical evidence now points to many of his ideas regarding airborne deep-penetration troops as having originated from fighting alongside Finnish troops tasked with similar missions in the Winter War).

Described by one his officers as “a military genius of a grandeur and stature seen not more than once or twice a century,” Charles Orde Wingate remains to this day a controversial, if not mythic, figure. Raised in the Plymouth Brethren faith, he regarded the old testament as the literal truth, and laced his fiery speeches and official writings with biblical rhetoric. But in the eyes of many, a worse offense was that he hardly looked like a proper British officer. In an army which celebrated impeccable “grooming standards,” he was often poorly turned out with untidy kit, filthy uniform and usually sported a beard. He was certainly different and remained in frequent contest with the regular army establishment over the idea of unconventional warfare. He gained his first experiences in irregular warfare as an Officer with the Sudan Defence Forces from 1928 to 1933. This small British-officered Arab force had been created in the 1920s in response to nationalist uprisings. Defense against a repeat of these and actions against tribes resisting government rule were the major concerns, and actions against criminal gangs operating in the large areas by the Sudanese and Ethiopian border were regular. Wingate was posted to command of an infantry company as part of a battalion near the Ethiopian border to lead patrols against ivory poachers and slave traders, and to show the flag. As at Woolwich, he was admonished by his commanding officer about his non-conservative talk and seemingly unconventional ways. Wingate took this to heart and began to moderate his ways and self-aggrandizing talk. For service in the Sudan presented Wingate with the chance to develop his professional skills.

Command of a self-contained, autonomously operating infantry unit of the Sudanese Defense Forces meant high quality officers were needed. And good junior officers had to be forged. Wingate would be the only European among an all-Sudanese force of Muslim Arabs and African Blacks numbering close to 300 patrolling a large area of the eastern Sudan.11 The commander was required to be both a military officer as well as a colonial administrator. In such a situation there was amply opportunity to develop tactical skills by way of maneuvering in remote areas, by attending to the welfare of the unit, by being responsible for their own military training, and by acting independently of higher authorities in combat. Wingate would learn much about leading men in combat, training and administrating them. Actions against poachers and gangs were maintained through infantry patrols, the tracking of movements, supported by aircraft spotting and patrolling. The area of the Sudan Wingate’s company operated in eastern Sudan demanded in itself the development of military and personal skills. The desert, hills and scrubland of eastern Sudan was primitive and remote, with little in the way of roads or mechanical transportation. Patrols were tests of endurance. Wingate soon realized facing the poachers and bandits problems common in counterinsurgency. These included the inability to easily separate the insurgents from civilians, with the small groups of bandits moving among the civilians and in areas frequented by nomads; the difficulty in achieving tactical surprise against forces operating among civilians and which were highly mobile and unpredictable; and the existence of a safe haven, with the criminals able to move regularly across the Ethiopian border. Wingate noticed the standard practices of mobile and irregularly timed patrols were inefficient and obtained poor results. As he wrote in a note, “The measures taken against poachers are limited to the maintenance of highly mobile patrols operating at irregular intervals and in various directions…such wide toothed and occasional combing has not the smallest chance of success in inhabited country.”

Instead of deterring or trying to locate and bring to battle the small poacher gangs by irregular patrols, Wingate found his success by developing other methods. He began to introduce deception, deceiving the enemy about his patrols’ ultimate destination and routes. He aimed to supplement such measures with achieving surprise from “using cover and concealment to surround the gangs, then surprise them with attack from all sides.”13 Such techniques led to success with one early patrol, from a combination of deception, information from the local population, good tracking, and military skills, all leading to the decimation of one armed criminal gang. Wingate’s vigorous writing up of this action brought praise from the Governor-General, stating it was a “very interesting narrative of a most successful expedition conducted with great dash and judgement.” Concentrating upon the known infiltration and exfiltration routes of the gangs, Wingate was at times able to successfully lay ambushes of border crossing points and tracks. He would write after one patrol that he chose his patrol march along the frontier across desert along the border to achieve surprise since, “by cutting across long stretches of waterless country each line…would be out of reach by warning by fleeing poachers…Should Abyssinians be poaching on Gallegu-Dindar the patrol would be between them and their base. This has special value in view of possible air cooperation.”15 Independence of command, the nature of the threat, and characteristic of the country meant Wingate “developed his skill – and taste – for raising, training and leading forces in his own image’ free of intervention from above.”

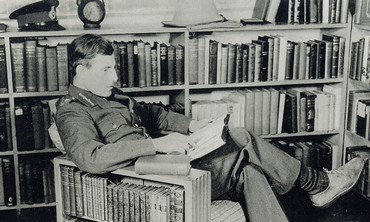

Orde Wingate in his and Lorna’s apartment, London, mid-1930’s (Note the trademark Pith helmet on the bookcase)

While in the Sudan, the joys of autonomy Wingate experienced was offset by some more unpleasant experiences. With the experiencing of death that came with his profession and fueled by the decent of a sister, Wingate came to the realization of his own mortality and slumped into a temporary existential depression. But another form of depression also began to haunt him at times, which he kept to himself, sharing only in letters to a girlfriend. The attacks of Clinical Depression he would later put it as an ‘attacks of the nerves.’ Wingate tried to cope with by using them as a fortifying experience, writing “To go through it and come out on the other side still holding on to one’s faith and one’s reason gives one something of the utmost value. I mean a knowledge of the depths, after that, the ordinary terrors of life are as nothing.” In keeping with his character, toward the end of his tour while on leave Wingate set off on a personal expedition of discovery into the Libyan Sand Sea at the eastern end of the Sahara Desert. He was one of several Europeans entranced by exploration and discovery in the unknown North African desert, and like others became romantically drawn into an attempt to find the legendary oasis of Zerzura. After cousin Sir Reginald Wingate helped arrange permission with the SDF, in January of 1933 Orde Wingate set off with small party of Arab guides and camels. Challenging himself and the men with him, he traveled by day under the sun to aid in surveying and lived on a Spartan diet. The party navigated past bleak, rocky landscapes, and journeyed through sand dunes amidst the uncharted western Egyptian desert. While the difficult journey of two months did not produce any evidence of Zerzura (it is thought to have been discovered farther south), Wingate did produce an article for the Geographical Magazine. More importantly he tested and discovered more limits of endurance. Marriage came in 1935, his wife Lorna’s quick mind and intelligence a match for him (they had met during Wingate’s voyage home in 1933 aboard ship when Lorna was 16 and Orde was 32 – they married just over a year later).

Posted back to England in 1933, Wingate was now a captain and returned to the artillery for three years, serving in units stationed in England. In September of 1936 orders came assigning captain Wingate to a staff position of intelligence officer in an army division due to be sent to British Palestine. It was here that he first attracted the attention of his superiors over 1937-38, when he formed Jewish “Special Night Squads” to tackle roving bands of Arab troublemakers (somewhat incidentally, Moshe Dayan was one of the young Jewish soldiers Wingate trained).

In early 1940 he was appointed to command the Atholl Highlanders Volunteer Battalion dispatched to aid the Finns in the Winter War. He led his Battalion of 1,000 men in battle alongside the Finnish Army, volunteering his battalion to fight first with the Finnish Parajaeger Division in their glider landings on the Karelian Isthmus in late Spring 1940, and then fighting in operations with the Finnish Osasto Nyrkki special forces units in lengthy raids deep behind Russian lines. It was in these missions, prior to which his battalion received training from the Finnish Army’s Osasto Nyrkki, that Wingate was exposed to the type of tactics and warfare that he would go on to apply with such success on a large scale in Burma later in WW2.

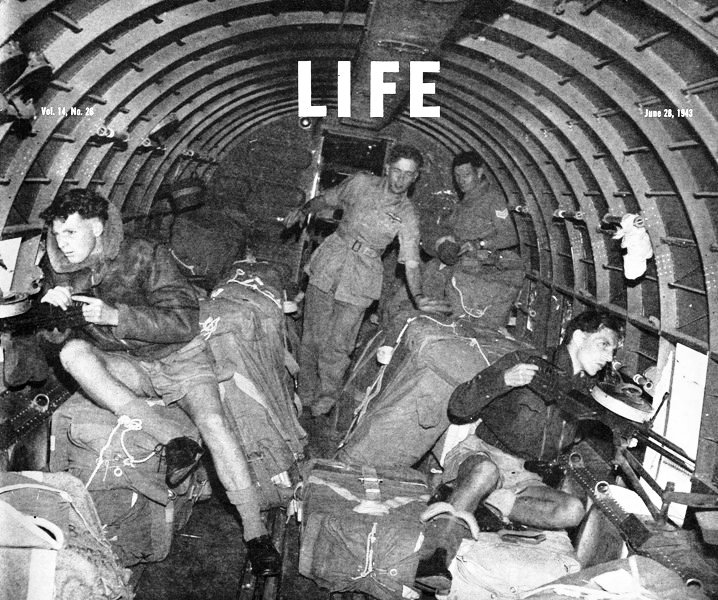

Atholl Highlanders led by Orde Wingate particpating in the Maavoimat Parajaeger landings behind the Red Army frontlines during the Spring 1940 offensive on the Karelian Isthmus.

Following the end of the Winter War, Wingate would be immediately sent to the Sudan to lead a force of irregulars in Ethiopia, whom he christened “Gideon Force” – after the old Testament hero who defeated 15,000 men with 300. With a strength of never more than 1,700 men, including a thousand spear and rifle-armed Ethiopian warriors, Wingate and “Gideon Force” went after the Italian army. In January 1941, he seized the Ethiopian border town of Ulm Idla, making it the first town to be liberated by his force. Next in March, combining daring with bluff, he drove a 6,000-strong Italian infantry unit, backed by several thousand irregulars along with artillery and mortars from the garrison fort of Bure, guarding the approaches into the Gojjam Province. But this victory proved a mere prelude of what was to come. Now reduced to only 1,000 troops, Wingate then routed a force of 12,000 Italians, plus thousands of Pro-Italian Ethiopian warriors from the key town of Debra Markos. Finally, Wingate chased after a group of about 10,000 Italians retreating from their last stronghold at Amba Alagi. Both sides ran out of food and their clothes were reduced to rags, but as cold weather set in that May, the Italians surrendered on the 19th. Gideon Force had captured some 19,000 enemy troops and kept occupied vastly greater forces. It was a brilliant effort, but for his troubles Wingate was given only a minor staff posting in Egypt. Depressed and suffering from malaria, he tried to kill himself by cutting his throat in a Cairo hotel. Only the influence of his superior, Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, allowed Wingate a further posting – to India, to command what would become the Chindits. It was tragic then that Wingate died at the height of his mortal fame in a plane crash in March 1944, returning from a visit to his forward troops in the field.