The Drip Torch – from this and an academic knowledge of WW1 Flamethrower Weapons, the Suomen Maavoimat began to experiment with military flamethrowers in the 1930’s

Interestingly enough, it was the Finnish experience with forest fire fighting techniques that led to a number of military programs and weapons which we will first summarize here and then go onto to look at each in detail in turn. When looking at the introduction of these weapons and pieces of equipment, it’s also important to keep in mind the continuous cross-fertilization of ideas and techniques between the military and civilian organisations. With a large percentage of Finnish men actively involved in the Suojeluskuntas, particularly in rural areas where farming and forestry was the primary occupation, and with an openness to experimentation and a willingness to consider ideas and tactical techniques and innovations originating from the bottom, rather than imposed from the top, there was always an avenue for even the strangest of proposals to receive at least some consideration. And some proposals that made their way up the chain were strange indeed….

Perhaps the first serious proposal to come out of the milieu of forest fire fighting was one regarding the military use of flamethrowers. In fighting forest fires, a technique that is often used is the controlled backburn. This is where firefighters set fire to an area ahead of a raging forest fire, aiming to burn up combustible material that could feed the wildfire but under controlled conditions. The backburn creates a manmade firebreak that aids in containing the fire. An early way of starting backburns was with a flaming piece of wood or brush, but by the 1920’s, a drip torch was more commonly used.

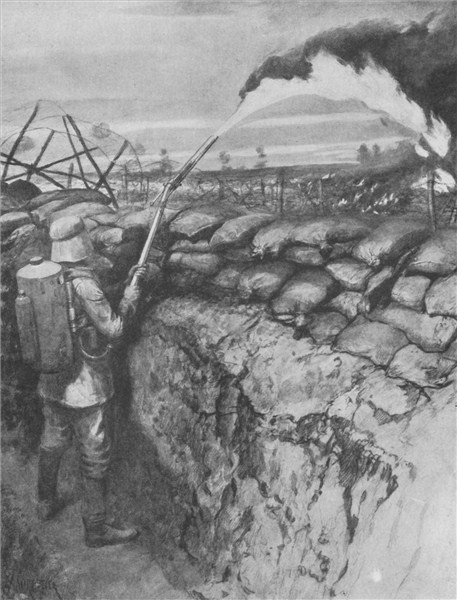

French soldiers make a gas and flame attack on German trenches in Flanders, Belgium, during WWI. The Finns had largely an academic knowledge of military flamethrowers

Prior to the early 1930’s the Suomen Maavoimat, as with most armies of the time, had no real experience with Flame Throwers as a combat weapon. Flame Throwers were of course known from World War I, where they were used in trench warfare, but the Maavoimat in the early 1930’s had no real experience or institutional knowledge of flamethrowers as a weapon. Once the Finnish military began to examine the Flame-Weapon proposal in detail, as they did in 1933, it rapidly became obvious that this was an existing weapon that had been used effectively in the First World War but which, post-war, had faded from view. Some initial research by Finnish Military Attache’s (who found themselves doing this kind of “real” work more and more through the 1930’s), produced the information that this weapon had actually been invented by the German engineer Richard Fiedler in 1900, and tested in secret by the Imperial German army the following year.

By 1912 the German Army had formed a Flammenwerfer regiment (of three battalions, with twelve companies in total). Each was equipped with man-portable flame-throwers consisting of a steel cylinder tank that was worn on the back attached to a 6-foot (1.8-metre) rubber tube and nozzle. The tank was subdivided into two: an upper reservoir containing a compressed gas to provide the pressure, and a flammable liquid (usually oil) in the lower. The gas propelled the liquid down the hose, which was ignited at the end of the nozzle by a wick. Flame could be projected for 20 yards (18 meters) for about two minutes, or shorter bursts could be obtained by igniting a cartridge for each burst, as with a shotgun. This principle of design has not changed since.

German flamethrower as used at Hooge, 30 July 1915

The weapon had been tested in action against the French in February 1915 in the Verdun sector, but was more famously used against British troops at Hooge, near Ypres, on the night of 29-30 July 1915. The six throwers that were used formed only a small part of a larger attack, aimed at inexperienced troops of the British New Army. Achieving complete surprise, the British trenches doused with flame were quickly taken, and the attack also had a great psychological effect on other defenders. The effect of the dangerous nature of the surprise attack proved terrifying to the British opposition, although their line, initially pushed back, was stabilized later the same night. In two days of severe fighting the British lost 31 officers and 751 other ranks during the attack. With the success of the Hooge attack, at least so far as the Flammenwerfer was concerned, the German army adopted the device on a widespread basis across all fronts of battle. The Flammenwerfers tended to be used in groups of six during battle, each machine worked by two men. They were used mostly to clear forward defenders during the start of a German attack, preceding their infantry colleagues and, while short ranged, were brutally effective.

They were undeniably useful when used at short-range, but were of limited wider effectiveness, especially once the British and French had overcome their initial alarm at their use. Quite aside from the worries of handling the device – it was entirely feasible that the cylinder carrying the fuel might unexpectedly explode – the operators of these flamethrowers were marked men; the British and French poured rifle-fire into the area of attack where Flammenwerfers were used, and their operators could expect no mercy should they be taken prisoner. Their life expectancy was therefore short as they operated perhaps the most hated and feared weapon in use.

The British Army also experimented with flame-throwers. However, they found short-range jets inefficient. They also developed four 2-ton throwers that could send a flame over 30 yards built directly into a forward trench constructed in No Man’s Land a mere 60 yards from the German line. These were introduced in July 1916 but within a couple of weeks two had been destroyed. Each was painstakingly constructed piece by piece, although two were destroyed by shellfire prior to 1 July 1916 (the start of the Somme offensive). The remaining two, each with a range of 90 yards, were put to use as planned on 1 July. Again highly effective at clearing trenches at a local level, they were of practically no wider benefit.

Flamethrower – WW1

Although these large flame-throwers initially created panic amongst German soldiers, the British were unable to capture the trenches under attack. With this failure, the British generals decided to abandon the use of flame-throwers. Similarly the French developed their own portable one-man Schilt flamethrower, of a superior build to the German model. It was used in trench attacks during 1917-18. The Germans produced a lightweight modified version of their Flammenwerfer, the Wex, in 1917, which had the benefit of self-igniting. During the war the Germans launched in excess of 650 flamethrower attacks; no numbers exist for British or French attacks. By the close of the war flamethrower use had been extended to tank-mounted flamethrowers. The advantage of a tank-mounted flamethrower was two-fold – the size of the tank meant that powered pumps could be used, rather than using pressurized gas – this extended the range of the weapon considerably, and the tank offered far greater protection to the crew operating the weapon.

Thereafter flame-throwers entered the arsenals of modern armies, usually as “pioneer” or “engineer” weapons, but as they had failed to achieve a spectacular success during WWI, they were not widely used. The lessons of late-WW1 with regard to tank-mounted flamethrowers were largely forgotten – only to be rediscovered, largely independently, by the Red Army in the 1930’s. The Red Army would go on to use flamethrower tanks against the Maavoimat in the Winter War. The Finns however, had not been taken by surprise by this weapon. Military Intelligence had identified that the Soviets were working on flamethrower type weapons, including designing a flamethrower tank, and Maavoimat soldiers, particularly the anti-tank gunners, had been informed and trained to identify and deal with these tanks as soon as possible.

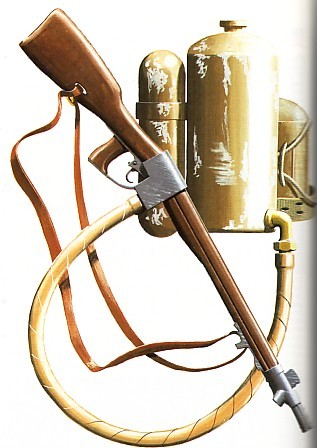

The rifle-shaped flamethrower was an idea the Red Army would later copy from the Maavoimat.

The Maavoimat itself had initiated its own research and development program into Flamethrowers in 1936, concentrating on man-portable versions as being more suited to the type of warfare the Maavoimat intended to fight. German expertise was sought and with the assistance of two of the engineers who had worked on the development of these weapons in WW1, an adequate design was soon forthcoming, with certain Finnish-inspired modifications. Among these were camouflaging the weapon by designing the firing mechanism to look like the standard Mosin-Nagant Rifle and the fuel tanks with a military knapsack-like appearance, thus reducing the chances of the operator being easily identified. In addition, early tests under the harsh conditions of a Finnish winter led to a problem unforeseen by the German designers, in that it was too cold to light the fuel. The production model incorporated a revised system which eliminated the problem.

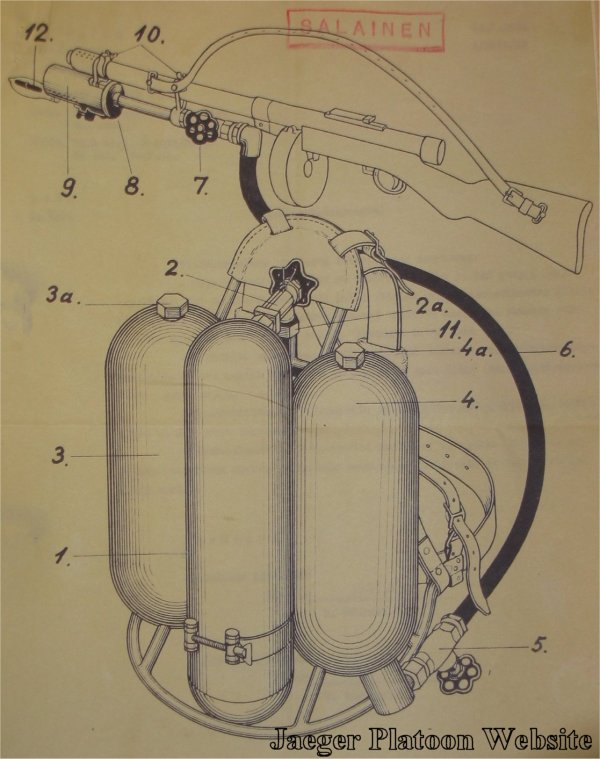

These Finnish manufactured man-portable flamethrowers (designated the Liekinheitin M/38) were capable of 10 “bursts” with a maximum range in the region of 120 feet. They used a version of jellied gasoline and had an 18 Liter fuel tank which used a container of pressurised nitrogen gas as a propellant. The mechanics of the device were fairly simple – two side by side tanks, one containing the fuel, the other containing the gas propellant. The two substances were mixed as they passed through a valve, the force provided by the compressed gas. The mixture was directed through a pipe and out through a nozzle. At this point the concoction was ignited and the sheet of flame produced. The flammable material was mixed with an adhesive which meant it would stick to whatever it hit, flesh included. The nozzle was fitted with a 10-chambered cylinder which contained the ignition cartridges. These could be fired once, each giving the operator 10 bursts of flame.

A Finnish Army soldier operating a Flame-Thrower on the Karelian Isthmus during the Spring 1940 counter-offensive

In practice this gave 10 one-second bursts. It was also possible to spray fuel without igniting it to ensure there was plenty splashed around the target, then fire an ignited burst to light up the whole lot. The flamethrower kit weighed some 64 pounds (29kg) making it somewhat heavy to carry and reducing the agility of the operator considerably. Unlike the flamethrowers of most other countries during World War II, the Maavoimat were perhaps the only ones to consciously camouflage their flamethrowers from the start, with the flamethrower “gun” disguised as a standard issue Mosin Nagant Rifles, and the fuel tanks disguised as a standard infantryman’s rucksack, to try to stop snipers from specifically targeting flamethrower operators. The vulnerability of the operator was compounded by the need to close to within pistol range of the enemy to be used effectively, meaning that generally the weapon was used when assaulting formations were up against fortifications such as pillboxes which were otherwise difficult to capture or destroy.

“Fire and Ice” – The Lanciaflamme Spalleggiabile Model 35 (which the Suomen Maavoimat subsequently named Liekinheitin M/39) in action on the Karelian Isthmus

The Maavoimat did not plan to use the man-portable flamethrowers defensively, the range was generally too short, the operator too vulnerable and the weapons had limited fuel. Finnish soldiers fighting on the Karelian Isthmus found them very effective against Red Army positions when the Finns took the offensive, as they often did tactically even when falling back. The Maavoimat used fire as both a casualty weapon and as a psychological weapon. They found that Russian soldiers would abandon positions in which they fought to the death against other weapons. Prisoners of war confirmed that they feared the flame-throwers more than any other weapon utilized against them.

Finnish soldier poses with flame-thrower Italian Lanciaflamme Spalleggiabile Model 35 in Märkälä in July 1940. (SA-kuva photo archive, photo number 24478).

As the pressure from the Soviet Union grew over the course of 1939, the Suomen Maavoimat determined that while units were equipped with these Flamethrowers they were not in numbers that were considered sufficient (only some 400 were in service, with some 1,000 being the goal). While these were on order and were being built at the rate of some 20 per month, with war looming on the horizon there was no time for half-measures. Manufacturing capability was limited, with many different priorities being addressed and in the greater scheme of things the Flamethrowers were low on the list of overall priorities. A decision was therefore made to purchase these weapons. An approach was made to Germany in June 1939, but for reasons that were at the time unclear (but which would later, in August of the same year, become all to clear), the Germans refused to manufacture or sell any to Finland.

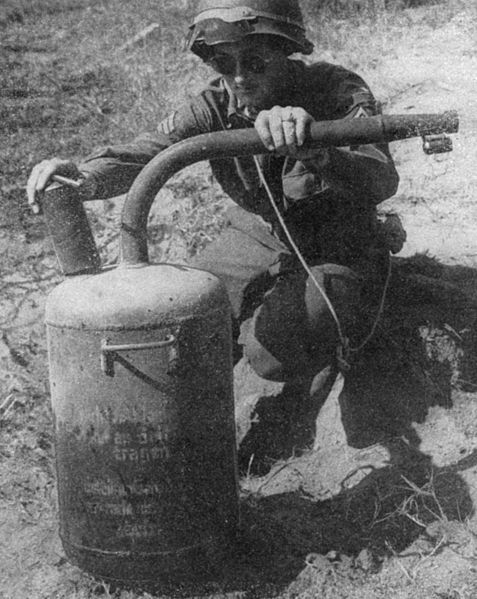

On the other hand, the Italians had portable flame-throwers on a large-scale (some 1,500 being used by Italian Army as of 1940) and were quite willing to do business with the Finns. Consequently, the Suomen Maavoimat decided to acquire additional flame-throwers from Italy and ordered 500 portable flame-throwers of the type Lanciaflamme Spalleggiabile Model 35, which the Suomen Maavoimat subsequently named Liekinheitin M/39 (Flame-thrower M/39). These flamethrowers were not delivered prior to the Winter War breaking out, but were delivered as a priority with the first wartime shipments dispatched from Italy, arriving in Norway in December 1939 and being railed to Finland through Sweden where they entered service in January 1940. These flame-throwers were promptly issued to Engineer Battalions of the Suomen Maavoimat and saw extensive combat use. The Italian Liekinheitin M/39’s had a range of 60 feet, weighed 25.5kgs and could fire 20-30 bursts of 1 second each.

The Liekinheitin M/39 consisted of three main components, the Fuel Tank, the Flame Tube with its Hose and the Lighter System. The fuel tank consisted of two cylinder shaped containers. These were divided by a horizontal inner wall into two chambers, the upper chamber contained nitrogen gas while the lower chamber contained the fuel. The Hose leading to the flame tube was attached low to the right hand side container. Nitrogen and fuel filling vents and a nitrogen pipe connecting the two cylindrical containers were on top of the fuel tank. The basic system used in this flame-thrower was the typical of flame-throwers of that era – the nitrogen provided pressure for spraying the fuel and once this was ignited it produced a considerable flame. Earlier Italian flame-throwers had used the fling-system for igniting the fuel, but the model delivered to Finland had been equipped with a lighter system, which was powered with electricity. This electric lighter could be powered either with dry batteries (one 18-volt battery, four 4.5-volt batteries connected in series or two 9-volt batteries connected in series) or a high-voltage inductor. This powerpack containing batteries or high-voltage inductor was an integral part attached to this flame-thrower.

But as always, the Maavoimat’s soldiers found more useful ways to utilise the weapon…officially known as the Kertakäyttöinen Liekinheittäjä (One-Shot Disposable Flamethrower) but unofficially referred to as the “Liekki” (slang for cigarette lighter)

The empty fuel tank weighted about 10 kg. The fuel tank contained 12 – 12.5 litres of flame-thrower fuel. The nitrogen gas in the upper chambers of its containers could be pressurized at up to 20 atmospheres. According to manuals, filling of the flame-throwers tanks had to be just before use, because the pressure would leak from the tank if it was stored for a long time. The typical way of using portable flame-thrower in combat was to fire short (about 1 second) bursts of flame and in this the M/40 proved quite good – it could do as many as 20 – 30 bursts with one fill. However range-wise it wasn’t quite as effective. Mainly due to low working pressure the maximum range of the flame was only about 20 metres or so, which was below average for portable flame-thrower of the World War 2 era. Also, as usual with portable flame-throwers, the weight of the weapon was an issue and slowed the movement of the flame-thrower team in combat. Due to weight and location of the valves operating of the flame-thrower, the M/40 demanded a crew of two men. The second man was usually equipped with a Suomi submachinegun and provided protection for the flamethrower operator, who carried only a pistol for self defence.

Organizationally, each Regimental Combat Group generally had a light Engineering Battalion (Pioneeri Joukkue) attached as part of its combat strength, and among other types of units, the Pioneeri Joukke included a separate Liekinheitin Joukkue (Flame-thrower Platoon) with a strength of 40 men in 3 Sections of 12 with a 4-man Platoon Command group. Two of these Sections had 4 Flame-Thrower Crews (with 3 men in each crew) with 2 Flamethrowers assigned to each Crew for a theoretical total of 16 flame-throwers to a Platoon (although in practice it was usually less than this as even with the Italian order filled the weapons were in short supply. Having two flame-throwers per crew was a standard tactical approach. Once a flame-thrower crew had run out of fuel in their first flame-thrower, they would simply take their second flame-thrower and continue fighting. The third section looked after maintenance, logistics and refueling. The flame-throwers needed to be re-fueled only after the 2nd flame-thrower had run out of fuel. Where necessary, portable flame-throwers were usually repaired in Weapons Depot 1 (located in Helsinki), although the Maintenance Section in practice during the War usually looked after basic repairs. Flamethrower Crews were generally assigned to combat for specific missions, where they fought under the command of the unit to which they were temporarily attached.

The Maavoimat’s One-Shot Disposable Flamethrower

An interesting variation also introduced by the Maavoimat was the “One Shot Flamethrower”. One of the issues the Maavoimat always faced was that where Specialist units were created, the effect was that soldiers were removed from front-line infantry units and placed in units where they might only occasionally be utilized effectively. To this end, the Maavoimat consciously limited the number of specialized flamethrower units but solved the need to have such a weapon readily available by designing and manufacturing what was in effect a disposable one-shot flamethrower weapon that could be carried and used by ordinary infantry where fortifications or enclosed defensive positions were expected to be encountered. The disposable weapon fired a half-second burst of flame of up to 27 meters (89 ft).

The Kertakäyttöinen Liekinheittäjä was designed and trialed in 1939 and began to be manufactured and stockpiled late in the same year. It was not used during the defensive phase of the Winter War, but as the Maavoimat moved over to the offensive on the Karelian Isthmus in Spring 1940, it was widely issued. It proved particularly useful to the troops as they whittled the Red Army out of their defensive positions and came to be a much-loved weapon. Small and relatively light, it was heavily used although later in WW2 it was considered more useful as a cigarette lighter or as a fire-starter.

A photo of a US soldier in Finland posing with a Suomen Maavoimat static flamethrower / flamemine. US Soldiers in Finland received some cross-training on Finnish weapons and this was likely taken at such a course sometime in 1943, after the first American and British units began arriving in Finland.

A third version, which was a larger and less portable version of the infantry flame-thrower, was used in defensive positions and to defend bunkers on the Mannerheim Line. These flame-throwers were usually carried into position on sleds or carts and had both a greater range and a far larger fuel capacity, with a 30 liter fuel tank. They were normally mixed in with other mines or emplaced behind barbed wire and could be command detonated or triggered by tripwires or other devices.

The mine consisted of a large fuel cylinder 53 centimeters (21 in) high and 30 centimeters (12 in) with a capacity of 29.5 liters containing a black viscous liquid made up of a mix of light, medium, and heavy oils. A second, smaller cylinder, 67 millimeters (2.6 in) in diameter and 25 centimeters (9.8 in) high, was mounted on top of the fuel cylinder. This contained the propellant powder which was normally either black powder or a mixture of nitrocellulose and diethylene glycol dinitrate. A 50 millimeter (2.0 in) flame tube was fixed centrally on top of the fuel cylinder, rising from the centre of the fuel cylinder and curved to extend horizontally approximately 50 centimeters (20 in).

When the mine was triggered, a squib charge ignited the propellant, creating a burst of hot gas which forced the fuel from the main cylinder and out of the flame tube. A second squib ignited the fuel as it passed out of the end of the flame tube. The projected stream of burning fuel was 4.5 meters (15 ft) wide and 2.7 meters (8 ft 10 in) high with a range of about 27 metres (89 ft), and lasted about 1.5 seconds. The mines were large and fairly heavy. They could not be moved rapidly but could be pre-positioned and used with the fixed direction discharge tube which could be dug-in and integrated with conventional mines and barbed wire in defensive works. When the mine was buried, normally only the flame tube was above ground and generally this too was well concealed, leaving only an inch or so of the muzzle exposed.

In winter, this could be blocked by snow and ice and care therefore had to be taken to position the devices where they could be kept clear. This limited their effectiveness somewhat in winter. However, where a number of them were used together as part of a pre-prepared and integrated defensive position they proved to be highly effective. The Maavoimat had limited numbers of these devices and used them only in conjunction with critical defensive positions on the Mannerheim Line. They came as a most unwelcome surprise to the Red Army infantry attacking these positions.

The Flamethrower M/Kuusinen, aka Flamethrower M/40

During the initial months of the Winter War, Finnish troops were largely using two types of portable flame-throwers – the Liekinheitin M/39 and the Finnish designed and built Liekinheitin M/38. While the portable flame thrower is extremely lethal within its own limited envelope – like most with flame-thrower designs, M/38 and M/39 had similar basic limitations. They could be only used at short range and due to being so large, heavy and clumsy, the soldier operating them was unable to carry or use any secondary weapon larger than a pistol. As a result soldiers using the flame-thrower as a weapon were basically defenceless if they encountered enemy soldier(s) that were outside effective range of the flame- thrower. Due to this the Finnish Army typically had another soldier equipped with a submachine gun assigned to protect the flame-thrower operator. Even with this the casualties amongst soldiers using the portable flame-throwers were not light.

Flame tube of Finnish flame-thrower M/40. Notice how the flame tube has been clamped to submachinegun barrel jacket. (Photo taken in Sotamuseo and courtesy of Jaeger Platoon website)

Towards the end of the heavy Winter fighting on the Isthmus, a Sergeant M. Kuusinen of Infantry Regiment 1 (Jalkaväkirykmentti 1) made a field invention that he hoped would solve this problem. His invention was a new kind of light flame-thrower which could be used with a submachinegun. Key to the invention was attaching the flame tube of the flame thrower to a submachinegun, effectively making the two weapons a single combination weapon. Fuel tanks for the flame-thrower were still carried on the back as in existing designs. Fuel was fed with vents and pipes from the fuel tanks to the flame tube. But now the soldier using the flame-thrower could also use the submachinegun if needed and no longer had to rely for assistance on other soldiers quite so much. Since the weapon was designed for attaching to the barrel jacket of any normal Suomi submachinegun, it didn’t require any changes to existing equipment.

With the manpower problems Finland experienced in the Winter War, fighting alone against the might of the Soviet Union, any innovation which would reduce manning levels whilst maintaining firepower was seen as worthy of consideration. It was exactly the type of invention that the Finnish Army was looking at the time. It was an obvious improvement to existing military weaponry, but demanding little in the way pf resources for testing and development, while also being within the limited production capabilities of Finnish industry, already hard pressed by wartime production needs and limited availability of raw materials. This prototype flame-thrower was named flame-thrower M/40. The prototype was first demonstrated to the General Headquarters of the Finnish Armed Forces (Päämaja) in April 1940.

This demonstration proved successful enough to lead to approval for further development and orders to make blueprints. An small experimental series was also ordered and manufactured for field-testing. The field-testing was carried out by troops of the Cavalry Brigade, the 21st Armoured Division and Engineer Battalion 35. For the most part the test results were positive. The basic concept worked as intended. The attachment of the flame-thrower to the Suomi M/31 submachinegun was successful and allowed the flame-thrower operator to use both weapons, hence removing the need for a submachinegun-man to cover the flame-thrower operator. The Flame-thrower M/40 was capable of 50 – 70 short flame bursts or a longer 40 – 60 seconds of continuous flame. This was a highly impressive performance compared to the two earlier model flame-throwers.

The downside was that the flame-thrower M/4o proved to be effective only to a range of 12 – 15 meters, with short one second long bursts of flame often reaching only 8 – 10 meters. This was considerably less with the other two flame-thrower designs already in use by the Finnish Army. When it came to range and maximum effective time of use, the test results showed considerable variation – the probable reason for this is that many of the nitrogen bottles used for providing pressure were leaking. Once again, the main reason for the large variation in performance seems to have been the quality of the raw materials used for manufacturing the prototypes.

Drawing showing structural details of flame thrower M/44. Notice the the two fuel tanks and the nitrogen bottle in between them. The red stamp SALAINEN indicates that the document used to be classified. Illustration courtesy of Jaeger Platoon Website

In general field-testing feedback suggested that the weapon was well suited to storming trenches, but due to the short flame ramge was poorly suited for other sort of combat situations (such as house to house fighting, which the Finns had little use for in any case). Some soldiers found it light while others still considered it too heavy considering the reduced range. They all agreed that it was handy and easy to use. The standard issue backpack frame adopted for the Flame-thrower M/40 made carrying this flame-thrower easier and comfortable than earlier earlier flame-thrower designs. But this new design also had other issues, which needed to be ironed out before planned mass-production. These included replacing existing vent types with a version that was easier to operate, elimination of protrusions and sharp corners (which might result in the flame-thrower operator becoming entangled or hurt himself) and lesser material issues. This lesser material issue being that front end of the leather submachinegun sling used to carry the weapon tended to become an unintended casualty of the flame-thrower flame and needed to be replaced with fire-proof material. If the nitrogen tanks were filled to full capacity the flame-thrower would also run out of fuel slightly before running out of nitrogen, which was in fact considered a useful feature.

Of the three units trialing the prototype, only Engineer Battalion 35 battle-tested the M/40 flame-throwers extensively. Combat-experience was less than positive. The system used for igniting the flame proved unreliable and the small pilot flame at the tip of the flame-thrower was considered to make operators vulnerable in night attacks, a tactic the Finns were using increasingly. Also the 21st Armoured Division had reported problems with igniting the flame in windy conditions, so apparently there was real room for improvements in that part of the design. The Finnish Army didn’t stop producing the flame-thrower M/40 while waiting the results of the test process. Manufacturing of parts needed for producing 1000 of these weapons had been ordered and was to be completed by 15th of July 1940. They were to be assembled in Weapons Depot 1 (Asevarikko 1). Each flame-thrower was to be delivered with five nitrogen tanks and three igniting sticks. The development project seems to have continued at least until 24th October of 1940 at which time there were plans for trying to improve range of the flame a little.

With the ceasefire and subsequent end of the Winter War fighting between the Soviet Union and Finland of October 1940, production continued while improvements based on testing and combat experience were also designed and ordered to be implemented. Following the end of the Winter War, all Flamethrower M/40`s were returned to Weapons Depot 1 (Asevarikko 1) for upgrading. Improved quality of parts and pressurization resulted in a range increase to 20-25 meters (from 12-15) although the number of short bursts that could be fired dropped. The tradeoff was considered worthwhile. A so-called “dead man’s switch” was now included which would extinguish the flame in case of the flame-thrower operator becoming wounded or killed. The pilot light lighting system was also replaced with a cartridge based system which proved more effective which proved more effective at night and also better suited to winter conditions. By late 1941 the mew and improved design was considered to be satisfactory and manufacturing was resumed, with all Finnish Army Regiments being equipped to TOE by mid-1943. Sergeant Kuusinen was rewarded with sum of 10,000 Finnish marks for this invention.

The Flamethrowers were used in the fighting against Germany over 1944-1945 but following the end of World War Two, they played a very small role in Finnish weaponry. Wartime flame-throwers were by then old-fashioned and had seen a lot of use. They probably were not in best of shape anymore and they didn’t see much post-war use. What is known suggests that the small number of existing flame-throwers saw limited post-war training use, but in the long run the Finnish military lost interest in flame-throwers and never moved to acquire any more modern flame-throwers.

Flamethrower Tanks

Conversely, the Red Army’s flamethrower tanks were not welcomed by the Maavoimat soldiers who faced them. In the 1930’s the Soviets had developed a series of flame tanks based on the T-26 light tank. Aware of the threat, the Maavoimat anti-tank gunners tended to target these as soon as they were identified. Early in the Winter War, the Maavoimat captured a number of these tanks from the Red Army. The Maavoimat itself did not however develop a Flamethrower Tank. Tanks within the Maavoimat were in short supply and it was felt that the tanks that were in service were better used as standard tanks equipped with high-velocity guns.

Knocked out Soviet OT-130 flame tank. The knocked out tank in the background is a Soviet BT-5. (Photo source Pala Suomen Historiaa website) Notice the “bulges” on top of the hull next to turret – these are the tops of the flame-thrower fuel tanks.

However, enough Red Army Flamethrower Tanks were captured to allow for the creation of a small number of Flame-thrower Tank Platoons (Liekinheitinpanssarijoukkue), each of which was assigned to an Armored Battalion (Panssaripataljoona) as a specialist unit. The only modification made by the Maavoimat before these tanks entered service in the Maavoimat was to repaint and to fit a Radio. Generally each of these Platoons was equipped with four of the captured Flamethrower Tanks and a strength of 23 men (one officer, eight non-commissioned officers and 14 men). Generally, the direction given to the use of these tanks was that they should only be used for specialist tasks which would benefit from their use in combat in offensive actions. In the Spring 1940 Karelian Isthmus, these Liekinheitinpanssarijoukkue were used with a high degree of effectiveness against Russian soldiers dug in in bunkers and strongpoints.

The OT-130 (the Soviet “OT” is an abbreviation for Ognemetniy Tank = Flame-throwing Tank and is supposedly post-war but mentioned in war-time Finnish documents) had a Crew of 3, weighed 10 tons, had a length of 4.65 meters, width of 2.44 meters and a height of 2.08 meters. The engine was a 90hp GAZ T-26 4-cylinder gasoline engine. Front Armour was 15mm, deck and turret top was 10mm, Ground clearance was 38cm and ground pressure was 0.61kg/square cm. The tank’s range was 170kms on road and 110 km off-road.

KhT-26 flame-throwing tank. This vehicle was produced in 1935 and partially modernized between 1938 and 1940, when new road wheels with removable bands and an armoured headlight were installed

During the 1940 Spring Offensive down the Karelian Isthmus additional large numbers of Red Army tanks and vehicles were captured (in addition to those that were destroyed). As one Suomen Maavoimat Regimental Combat Group commander was quoted in a British newspaper as saying in response to a question as to what the British could do to help further: “Ask Stalin to send more Red Army tank units, we’d like to add more tanks to our Armored Divisions.” Overall though, the Suomen Maavoimat wasn’t overly impressed with the Soviet flamethrower tanks. Their flame-throwers were unreliable and somewhat ineffective and were also considered wasteful in their use of fuel and the gun-tanks were considered more useful and versatile. As a result, after the Karelian Isthmus was recaptured, the Maavoimat decided to convert the ex-Soviet flamethrower tanks into gun-tanks, a task which was carried out by the Armour Centre (Panssarikeskus) and Lokomo Works (Lokomon Konepaja).

The main effort involved in this conversion was replacing the flame-thrower with the usual captured Soviet 45-mm tank gun. In addition to this the conversion work consisted of:

• Removal of flame-thrower fuel tanks, pressurized air tanks and their tubes.

• Installing seats for crew (the seating arrangement in the Flamethrower Tanks was bit different from the standard gun-tank and an extra seat for the 4th crewmember was fitted in most of these converted tanks) and adding ammunition racks (for main gun ammunition and for magazines of the DT-machineguns).

• Adding necessary optics (gun sights and periscopes).

• Removal of rear turret machinegun, if the tank had previously been equipped with one.

Most of the converted tanks were also equipped with an additional hull-machinegun and a fourth crew member (hull machinegunner) was added to the crew. After Finland entered WW2 against Germany, these older captured Soviet Tanks were retained for training purposes only.

(All information on Soviet, Finnish and Italian Flamethrowers as well as on Soviet Flamethrower Tanks and Photos is courtesy of the Jaeger Platoon Website – http://www.jaegerplatoon.net – Please note that this is an Alternative History and while real historical information has been used, some of the content may have been adapted for the purposes of this ATL – and many thx once again for letting me reuse your content Jarkko – any mistakes are mine….If you`d like to get the genuine scoop on Finnish weapons, I can only recommend Jarkko`s amazingly detailed website as a reference))

Return to Table of Contents

Previous Page:

Next Page:

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2015 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2015 Alternative Finland