While the Ilmavoimat ordered 40 Curtiss Hawk’s for earlier in 1937, and the Merivoimat eventually confirmed an order for 20 Brewster Buffalo’s late in the same year, the Ilmavoimat was also looking for a heavy “Bomber destroyer” fighter and in early 1937 began initial discussions with Fokker regarding the Fokker G1 Fighter.

The G1 was designed and a first prototype was built in 1936 by Fokker head engineers Beeling and Schatzki, with the design and building of the prototype taking just 7 months. Work had actually started in March 1935 after receipt of a specification from the French Airforce for a two engined heavy fighter that was supposed to utilize French equipment: Hispano Suiza engines, instruments, and a landing gear to be delivered by OLA. French interest disappeared after several French designs subsequently appeared. Fokker however thought the design had potential and continued development on their own initiative as “Project 129”. The aircraft had a twin boom configuration, something which was not new, but which caused a great public sensation when first seen. In the fuselage there was room for both the crew and the aircraft’s armament. The armament was in the nose: the prototype had 2x23mm Madsen cannon with 100 shells and 2×7.9mm machineguns with 550 cartridges, and was connected to the framework for the front of the central pod.

Like all Fokker aircraft of the period (and many aircraft constructed by other manufacturers at this time), the G1 was of mixed construction; the front of the central pod and the tail booms and tails were built around a frame of welded steel tubes covered with aluminium plating. The back of the central pod, however, as well as the wings, had a wooden frame, covered with triplex, a technique also used in Fokker’s successful passenger aircraft at that time. The steel tubular frame was attached to the front wingspar. The many small windows in the rear part of the fuselage were made out of Perspex and hung in a Dural framework. The belly of the fuselage had two large doors with perspex windows, helpful for observation. There was also a bomb bay that could hold a 400 kg bombload. The rear part of the fuselage ended in a beautiful conical turret that could turn completely around its axis, giving the rear gunner a full 360 degree aim. The machine gun could be aimed by opening perspex panels running the full length of the turret. The wingspars went through the cockpit, right behind the pilot, and before the rear gunners compartment. 550 Liter fuel tanks with a reserve tank of of 150 liters were located in the wing, between the fuselage and the engine nacelles.

The wing edges, on both sides of the engine, contained the oil tanks. The outer parts of the wings were also made out of wood covered with triplex, glued together the same way Fokker used with their successful range of passenger planes and with plywood arches. All control flaps were made out of a Chromemolybdenum steel frame covered with linen. From the firewall on, the engine covers and struts were made out of aluminum. Directly behind the landing gear compartments the twin booms were again made of aluminum. The horizontal stabilizer, between the tail booms was also made out of aluminum and had the tail wheel in the middle, while the rudders were covered in canvas. The main landing gear was retractable into the engine nacelles.

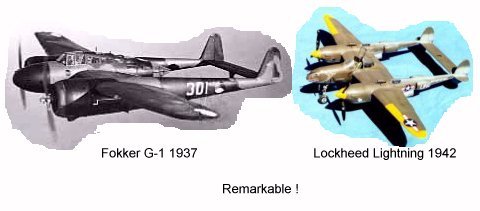

Fokker decided to send the G1 to the Paris Air Show (which in those days did not have a flying display but only a static exhibition in the Grand Palais) even before its first flight, anticipating a lot of interest. His expectation was correct, with the G1 becoming the sensation of the show. The prototype was hung from the roof with steel cables between aircraft of the Polish and Russian manufacturers. The concept of a twin-boom twin-engined fighter, later adopted for the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, was quite revolutionary at the time, and the new aircraft was the centre of much critical appraisal. Interest was also generated as a result of the heavy armament of 8 machine guns in the nose. The G1 was given the nickname Le Faucheur (Mower) by the French and “Reaper” by the English, nicknames that pointed to the heavy armament in the nose. There is some doubt that the French came up with that name themselves; a lot of people think that Fokker made that name up himself. While the G1’s twin-engine, twin-boom design was also used for the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, conceived and designed around the same time, it is unlikely that the P-38 Lightning designed was derived from the slightly earlier Fokker G1 design.

After the Paris Air Show, the G1 was taken to Eindhoven/Welschap airfield, from where its first flight was made on 16 March 1937. A Czech pilot, Maresc, main test pilot for the Czechoslovakian government and senior pilot of the manufacturer Avia, made the maiden flight with the prototype (registration code X-2, and painted in green with medium blue belly). The flight went without flaws and after 20 minutes the pilot landed again. For the audience the G1 was a spectacularly promising plane that had minor problems. After 4 test flights this proved to be not quite so true. On the fifth test flight, problems occurred with one of the Hispano Suiza engines – due to overheating the engine broke down and threw several parts out through the exhaust pipes. Before this incident it was already well known that the Hispano engines were badly designed. One of the tail booms was also damaged.

The G1 was initially powered by two 559kW Hispano-Suiza 80-82 counter-rotating radial engines, but problems with these prototype units (they used too much oil) resulted in a change to similarly rated Pratt & Whitney SB4-G Twin Wasp Juniors during rebuilding (after the G1 suffered brake failure and rammed a hangar at Schiphol on 4 July 1937). A quick and dirty solution was to add extra oil coolers, placed underneath the engines. This solution was not very elegant and finally Fokker did choose another engine, the Pratt & Wittney Jr. SB4-G This engine produced less power but was much more reliable. For the Dutch Air Force, other engines were mounted; the more powerful Bristol Mercury VIII engines that where also used for the Fokker DXXI (this engine was specified as standard by the Dutch Air Force for all its aircraft). The aircraft design consequently had to be adjusted as the engines had a larger diameter and a different shape and the propellers were larger, meaning the engines had to be moved further away from the fuselage. The wider central wing meant that the fuel tank capacity could be increased.

The tail design was also slightly changed. The redesign incorprated higher landing gear to keep the propeller of the ground. These changes were incorporated in the X2 prototype which satisfied the LVA. Actually, the designers wished to replace the engines with Rolls-Royce Merlin engines (which would have made the G1 the fastest fighter in the air at the time), but those were not available for export from the UK. The design of the nose section of the G1 also caused problems. The armament chosen by the Dutch Air Force, 8 machine guns in the nose, caused the aircraft to become nose-heavy and made the plane difficult to manage during take-off and landing. Several G-1’s ground looped during landing and a good solution for this problem was not found although in 1939 there was a plan to give the G.1 a different setup. In this design modification, 4 of the machineguns were relocated to the bomb bay firing from underneath the pilot. In use with the Dutch, the machineguns also proved to be very unreliable, partly due to the low temperatures at high altitude. This sensitivity to subzero temperatures was partially resolved by using a different lubricant. Despite that the armament kept on causing problems; firing them on the ground was no problem, but in the air usually 2 or 3 of them jammed. This problem was not solved by the Dutch.

The Ilmavoimat Commander, Aarne Somervalo, expressed interest in buying one completed aircraft from Fokker together with a manufacturing license. It is not documented, but it is probable that Somervalo planned to perhaps switch the Bristol Blenheim manufacturing line over to the Fokker G1s. An Ilmavoimat team visited the Fokker factory in June 1937 and carried out a series of comprehensive test flights. Captain Gustaf Magnusson test flew the Fokker G1, reaching a speed of 650km/h (403.9mph), which attracted considerable attention in the local press. Ilmavoimat Captain Erkki Olavi Ehrnrooth also test flew the G1, although he damaged the booms and tail in an accident. The aircraft was repaired and Ehrnrooth flew more test flights. In his and Magnusson’s opinion, the G1 was a good aircraft, but would make a better fighter if the design was modified to focus on on this particular requirement and less on a multi-role fighter bomber.

Fokker G1 being flown by Ilmavoimat Captain Erkki Olavi Ehrnrooth in June 1937 during the Ilmavoimat evaluation

Somervalo agreed – his major concern was the air defence of Finland against Soviet bombers and he saw the Fokker G1 meeting this need very effectively. He also saw the VL Wihuri filling this role, but at this stage the Wihuri was very much an unproven design – and by the time of these discussions the G1 was very much a real flying aircraft. Design modification discussions with Fokker took place in August 1937, resulting in a major redesign of the aircraft, the completion of an Ilmavoimat prototype in November 1937 followed by a further test series from which the results met or considerably exceeded all expectations. The Ilmavoimat placed an order for 15 Fokker G1’s in December 1937 and at the same time purchased an unlimited manufacturing license.

The modifications that the Ilmavoimat specified were that the Finnish G1’s were to be single-seaters, configured as a fighter-only, with no bomb bay (although inner-wing hard points for 22×500 lb or 4x250lb bombs were specified, giving the G1’s an effective ground attack capability), the fuselage size very considerably reduced as there would be no radio operator and no rear-gunner, with consequent substantial weight-savings. Also, the Finnish G1’s were to be powered by the more powerful Hispano Suiza 12Y engines (920 hp vs the 840hp Bristol Mercury or the 825hp Pratt & Whitney) engines which were starting to be built under license in Finland by the State Engine Factory (initially intended for the VL Wihuri) and were equipped with an additional fuel tank, increasing the range to some 1,300 miles. The considerably more powerful engines and the large weight reduction consequent on the aircraft being a single-seater with no bomb load and a substantially decreased fuselage pod increased the speed substantially, giving the aircraft a maximum speed of 340mph, making it one of the fastest fighters in the air at the time. The resultant aircraft looked very similar to the later Lockheed P-38 Lightning, indeed, the aircraft were almost indistinguishable when seen side by side. Finland specified that the aircraft would be shipped without the engines or armament– these would be installed in Finland with the assistance of Fokker technicians (the first aircraft completed was test flown from the factory with engines and armament shipped from Finland. Armament for the Finnish version consisted of 4×12.7mm forward-firing machine guns mounted in the nose together with 4x20mm Hispano Suiza cannon with 150 rounds each.

The reduction in size and weight of the fuselage, together with the massive nose-mounted armament, changed the centre of gravity of the aircraft to the extent that a nose-wheel was added to the Finnish aircraft. Clustering all the armament in the nose was also unlike most other Finnish fighter aircraft, which used wing-mounted guns with trajectories set up to crisscross at one or more points in a “convergence zone.” Guns mounted in the nose did not suffer from having their useful ranges limited by pattern convergence, meaning good pilots could shoot much farther. A Fokker G1 could reliably hit targets at any range up to 1,000 yd (910 m), whereas other fighters had to pick a single convergence range between 100 and 250 yd (230 m). The clustered weapons had a “buzz saw” effect on any target at the receiving end, making the aircraft very effective for ground strafing as well.

Ilmavoimat Fokker G1 – photo taken shortly after entering service with the Ilmavoimat in October 1938

The first six production G1s were received by the Ilmavoimat in October 1938 and, after fitting with the Finnish-license manufactured Hispano-Suiza engines and armament, were test flown in a series of exercises against other Finnish fighter aircraft. It was found that, while the Fokker G1 was not the most maneuverable fighter in the air, its sheer speed, particularly in a diving attack, combined with the devastating punch of its guns made it a fearsome foe when flown to maximize these advantages. While the G1 could not out-maneuver the Ilmavoimat’s single-engined fighters, its speed and rate of climb gave the pilots the option of choosing to fight or run, and in target shooting exercises, its focused firepower was found to be deadly. The concentrated, parallel stream of bullets allowed accurate shooting at much longer distances than fighters carrying wing guns. However, if faced by more agile fighters at low altitudes, G1s could suffer heavy losses and they could be avoided by opposing fighters because of the lack of dive flaps to counter compressibility in dives. Opposing fighter pilots not wishing to fight would perform the first half of a Split S and continue into steep dives because they knew the G1s would be reluctant to follow. On the positive side, having two engines was seen by the pilots as a built-in insurance policy, esecially after having an engine fail en route or in combat.

Two other problems were encounted in early exercises. The unique design feature of outwardly rotating counter-rotating propellers meant that losing one of the two engines on takeoff created a sudden drag, yawing the nose toward the dead engine and rolling the wingtip down on the side of the dead engine. Normal training in flying twin-engine aircraft when losing an engine on takeoff would be to push the remaining engine to full throttle; if a pilot did that in the G1, regardless of which engine had failed, the resulting engine torque and p-factor force produced a sudden uncontrollable yawing roll and the aircraft would flip over and slam into the ground (as happened with one early aircraft). Procedures were identified and taught to allow a pilot to deal with the situation by reducing power on the running engine, feathering the prop on the dead engine, and then increasing power gradually until the aircraft was in stable flight. Single-engine takeoffs were possible, though not with a maximum combat load. There were also early problems with cockpit temperature regulation: in the cold conditions of a Finnish winter and at high altitude, pilots were often too cold as the distance of the engines from the cockpit prevented easy heat transfer. VL made modifications to the heating system to try and solve this problem but it was never fully rectified.

The Fokker G1 in ground-attack mode – with the ability to carry 2×500 lb or 4×250 lb bombs combined with its superlative nose-mounted battery of cannon and machineguns, the G1 was a lethal ground-attack fighter.

However, despite these limitations and problems, the performance was seen as being exceptionally good, so good that the Ilmavoimat ordered a further 12 G1’s from Fokker in the first quarter of 1939 (after the initial shipment had been recieved) as it was taking time for the VL production line to switch over and come up to speed. All of the first batch of 15 G1s had all been shipped to Finland by December 1938. Finland had, as mentioned, also purchased a license to build the Ilmavoimat version of the Fokker G1 and, with a license for unlimited production and the designs in hand, had in early 1938 begun to switch the VL Blenheim production line over (it had been intended to construct the VL Wihuri’s, but the differences were so major that it made more sense to build a new assembly facility for the Wihuri’s and use the old Blenheim line for the Fokker G1’s).

The first VL-built prototype flew in mid-1939 and the Finnish-built aircraft began entering service in late October 1939, with two per month initially rolling off the production line. Finnish built Hispano-Suiza engines, machine guns and cannon were fitted along with many fittings from the old Blenheim line (instrutments, wheel assemblies, etc) and the aircraft test flown. The first batch of 4 VL-built Fokker G1’s were delivered to the Ilmavoimat in early January 1940, in the midst of the Winter War. These aircraft entered service, replacing combat losses and losses due to accidents (primarily due to engine-failure on takeoff and to ground-looping on landing, a problem which was never completely eliminated). A further batch of 6 aircraft was received in April 1940, entering service in time to replace further losses prior to the spring 1940 Offensive.

The second batch of 12 G1’s ordered from Fokker in March 1939 began to be shipped in July 1939. These later G1’s were fitted with the bubble canopy developed for the Ilmavoimat’s Miles M.20 Fighter and also with armour protection for the pilot as well as self-sealing fuel tanks. With the Soviet Union growing ever more threatening, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 (with the secret clauses relating to the Baltic States of which Finland was aware) and the invasion of Poland by both Germany and the Soviet Union in September 1939, the Ilmavoimat barely managed to have all 12 of the second batch ordered from Fokker in service before the Winter War broke out. At the same time, with the international situation growing more threatening and the Soviet Union putting more and more pressure on Finland in negotiations, the Ilmavoimat decided to purchase the earlier version of the Fokker G1’s that had been constructed for the Spanish Republican Air Force. These 12 Fokker G1’s were consequently shipped to Finland in July 1939. Performance was substantially less than the Hispano-Suizaienginned Fokker G1’s constructed for the Ilmavoimat, but the aircraft were delivered to AB Flygindustrie in Sweden, where they were substantially modified and re-engined into a similar configuration to the Finnish aircraft.

These 12 G1’s entered service in November 1939, along with the first two VL constructed G1 aircraft, meaning that the Ilmavoimat was able to field two squadrons (some 40 aircraft) of Fokker G1’s on the outbreak of the Winter War – and VL production, which started at 2 per month, had doubled to 4 per month by April 1940. By the end of the Winter War in September 1940, the Ilmavoimat fielded some 50 Fokker G1-I’s in total. The G1 continued to be built through WW2, with continuous improvements and modifications, including replacement of the Hispano-Suiza engines with newer and more powerful engines. Never receiving the publicity of the Lockheed P38 Lightning (and in fact often being mistaken for the P38 after Finland entered WW2 against Germany) it was as good a Fighter as its better known comrade and in the Winter War, was used with good effect to decimate both Soviet bombers and fighters.

As delivered to the Ilmavoimat, the Fokker G1 Fighter flew with a single pilot and was powered by 2x1000hp Hispano-Suiza 12Y engines, had a maximum speed of 340 mph, a ceiling of 32,800 feet and a range of 1,300 miles. Armament consisted of 4 x Hispano 20mm cannon with 150 rounds each (2 AP, 2 tracer and 2 HE ammo belt composition) and 4 x 12.7mm Browning MG53-2 machineguns with 500rpg. The rate of fire was about 650 rounds per minute for the 20mm cannon round (130 g shell) at a muzzle velocity of about 2887 ft/s, and for the 12.7mm MGs (43–48 g), about 850 rpm at 2,756 ft/s velocity. The combined rate of fire was over 4,000 rpm with roughly every sixth projectile a 20 mm cannon shell. Time of firing for the 20 mm cannon and the 12.7mm machineguns were approximately 14 seconds and 35 seconds respectively. With more powerful engines, the Finnish G1’s could also carry an effective bombload when operating in a ground attack role. The Inner Hardpoints could carry 2×500 lb (227 kg) or 4×250 lb (113 kg) bombs.

OTL Note: The Fokker G1 Heavy Fighter is an interesting “might have been” that “almost was” as far as the Finnish Air Force was concerned. Finland actually ordered 26 of these aircraft, but construction was only partially completed before the outbreak of the Second World War. If they had been completed and delivered, they would have been a useful adjunct to the Ilmavoimat’s front line fighter strength. The small number of Fokker G1’s that were in service with the Dutch Air Force (Luchtvaartafdeeling) certainly made an impact on the Luftwaffe in the limited air combat that took place after Germany invaded the Netherlands.

The Fokker G1 was a heavy twin-engined fighter plane comparable in size and role to the German Messerschmitt Bf 110 and the British Mosquito and somewhat similar in concept and appearance to the American Lockheed Lightning or Northrop Black Widow. Designed as an “air cruiser” (i.e. patrolling the air space and denying it to enemy planes, especially bombers; a role seen as important at the time by the followers of Giulio Douhet’s theories on air power) the Fokker G.1 was a twin-boom, twin-engined fighter aircraft that could also be used for ground attack and light bombing missions (it could carry a bomb load of 400 kg). It was intended for a crew of two or three (a pilot, an optional bombardier/radio operator and a rear gunner).

With its heavy armament and clean lines, the G1 was the best aircraft the Netherlands Air Force had in May 1940. When Germany invaded the Netherlands on May 10, 1940, 23 of these G1’s were ready (12 with the 4th Fighter Group at Alkmaar and 11 with the 3rd Fighter Group at Rotterdam / Waalhaven), with four more R-1535-equipped aircraft originally intended for Spain also in services. The Germans were surprised by the ferocity of the supposedly docile Dutch. One advantage of small size is that the Belgian and Dutch aircrews tended to be of high quality – turnover of Air Force personnel was low, and as it was difficult to get into the air services, they developed into something of an elite. One enduring myth from the campaign is the destruction of the Dutch Air Force on the ground by the Luftwaffe at dawn on 10 May 1940. Only at Bergen airfield on the North Sea coast west and north of Amsterdam were the Dutch caught on the ground, where they lost a dozen of the new Fokker G1 fighters. This loss was bad enough, but at every other airfield, the Germans met a determined defence. The G1 squadron at Waalhaven got eight of its 11 aircraft into the air. The ensuing air battle proved to be one of the most lopsided of the whole battle of France. The Luftwaffe lost 13 aircraft shot down (eight bombers, three Messerschmitt fighters and two Ju52s). Just one G1 was lost (the tail gunner of this aircraft was killed by bomb splinters while running to his plane).

Noteworthy was the action of Lieutenant Bram van der Stok, based at De Kooy, during another of the largest dogfights of the first day. Eight Dutch Fokker D21s from De Kooy faced nine Messerschmitt Bf109Es from II(J)/TrGr186 (part of the air unit slated to serve on the never completed German aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin). It was another surprise defeat for the ostensibly superior Germans. Although slower, the Dutch used the better manoeuvrability of the Fokker D21 to advantage. Five 109s were shot down, including the squadron leader’s machine, with another two damaged. The Dutch lost no aircraft. After May 1940, van der Stok escaped to Britain and flew Spitfires with the RAF until he was shot down and made a POW. He participated in the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III in March 1944, and became one of only three POWs to successfully get away. He eventually came to command No. 322 Squadron. In the film The Great Escape, his character was turned into an Aussie.

Over the next five days, the Dutch Air Force fought a grim battle of attrition, heavily outnumbered and with only negligible aid from the French and British. Most action took place on 10 May, the first day, with more than 100 sorties. The Dutch faced alone the full onslaught of the whole of Luftflotte 2’s 600 combat aircraft (not counting the air transport fleet of 500 Ju52s). Managing only about 30 sorties on May 11, it looked as if the Dutch Air Force had collapsed, yet the next day close to 100 sorties were again mounted. The two single largest concentrations of Dutch aircraft, less than a dozen aircraft each, were seen on 12 May during the battle for the Grebbeberg, but this day proved to be the last gasp. Still, on the morning of 14 May, just before the capitulation of the Dutch Army, the Air Force was mounting defensive patrols, singly or in groups of two, three or four, with whatever could be scraped together, patched up and sent into the air: seven D.21s, four G.1s and a C.5

Of the Dutch Air Forces Fokker G1’s, one G1 squadron was almost completely destroyed on the ground, but the other scored thirteen confirmed kills. The Gls were successful in destroying several Junkers Ju 52/3ms during the early stages of the German invasion, but by the fifth day, when Dutch resistance ended, only one G1 was in fighting condition. Twelve were destroyed on the ground, nine were lost in battle and a Mercury and a Wasp were lost by accident. During attacks on German troops on the Grebbe-linie, several Fokker G1s successfully strafed the German lines while under very heavy anti aircraft fire. Dutch pilots had discovered they could evade the Luftwaffe fighters by flying very very low. This was called “HuBoBe” flying, which stands for Huisje Boompje Beestje, freely translated as: HouseTreeAnimal flying, because they would be so near the ground.

The Germans occupied the Fokker factory, ordering completion of 12 Gls that had been intended for Finland. These were used subsequently by the Luftwaffe as fighter trainers for Me-110 crews and for testing. There are no cases known of German G1’s participating in combat. Test flights from the factory were made under German supervision, but on 5 May 1941 two Dutch pilots (Leegstra and Vos) flying from Schipol on a test flight succeeded in evading an escorting German-flown G1 and escaped to England. Their G1B was taken to the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, for examination, and used subsequently by Phillips and Powis (Miles Aircraft) at Reading for research into wooden construction, specifically to test the wooden wing for the English climate. A total of 62 G1’s are believed to have been built – none survived the war. Only a replica in the Dutch Air Force Museum in Soesterberg remains. There is no clear count of how many G1 ‘s eventually fell into German hands. It can be assumed that several Dutch Mercury and many Wasp versions fell undamaged into German hands. It may also be assumed that a number of Danish aircraft were seized by the Germans as well as 20 of the aircraft that were to have been delivered to Finland. The Luftwaffe almost certainly had between twenty and thirty in service.

During the short development period of the test G1, a number of variations were explored. None of these came to fruition with the exception of the fitting of one G1 prototype with an observation dome under the fuselage. This was nicknamed the “Bathtub” and was not a success. However, Sweden, when they placed an order for the G1, ordered 12 of the aircraft with these observation domes. Besides the Netherlands Air Force, several foreign air forces also showed an interest in the G1. The aircraft was originally built to a French Air Force specification, but the French preferred French-built aircraft such as the Dewoitine D.520 or the Breguet 69 and did not, in the end, place orders for any G1’s. The Danish Air Force showed great interest in the aircraft as a dive bomber. To test this concept, the 302 prototype was equipped with dive brakes, similar to that of the Junkers Ju 87, and extensively tested. Denmark subsequently ordered 12 G1’s for use as dive bombers. These were to be built under license (a licence-production agreement was in negotiation when war broke out), and were not completed because of the German invasion, but were delivered in parts and subsequently captured by the Germans during Operation Weserübung before they could be assembled. (Just before the German invasion of Denmark, an order for a further 24 aircraft was placed. These additional aircraft were never delivered). The rest fell intact in German hands.

Overall, interested countries were: Spain (26 or 36 ordered, none delivered), Sweden (18 G1-A’s and a 77 machine manufacturing license ordered on 5 April 1940, none delivered and none built under the license), Estonia (9 ordered, none delivered), Finland (26 ordered, none delivered) as well as Belgium, Turkey, Hungary and Switzerland. Test Pilots from Finland, Sweden, Belgium and Turkey flew the aircraft. Licensing negotiations were also underway with Manfred Weiss in Hungary. Due to the German attack on the Netherlands, no aircraft were delivered to these countries. The Dutch embargo on weapons exports before World War II had killed the Spanish order (these aircraft were taken over by the LVA), but the Finnish batch was under construction when the Winter War broke out and a ban was then placed on its export. After lengthy negotiations a contract was drawn up to permit the G1B’s export on 17 April 1940, by which time 12 had been completed, apart from armament. Swedish Air Force officer Bjorn Bjuggren wrote in his memoirs how he test-flew the aircraft in the late 1930s and found it tricky to use as a dive-bomber because of the difficulty in breaking out of the steep dive (the P-38 Lightning had similar problems breaking out of dives).

In the end, two versions were actually built: The first production G1’s were produced as a single-seat series for the Spanish Republican Air Force, who had ordered 26 or 36 aircraft (depending on the source). Construction of these aircraft began in the autumn of 1937, but the embargo on the sale of military equipment to Spain meant the delivery of the aircraft was halted before the aircraft left Fokker’s hands.After the final defeat of the Republicans in 1939, Estonia had decided to take over part of this order. Ten of the aircraft were assembled when Germany attacked the Netherlands and the Dutch Air Force took these over, although the Dutch had difficulties finding armament for these aircraft, eventually managing to arm only four of them where, from May 10 1940 on, they joined combat operations. Demonstrations had already been given to the Netherlands army air corps at Soesterberg, and considerable interest was shown, resulting at the end of 1937 in an order by the Dutch Luchtvaartafdeeling for 36 of the larger three-seat version G1s with Bristol Mercury VIII engines (the standard engine used by the Dutch air force), in order to equip two squadrons. This decision brought delays because although G1A production began immediately there was a hold-up in the supply of engines. Thus the first production aircraft to fly, actually the second of the batch, became airborne only on 11 April 1939. It remained with the makers for production testing and modifications, and the first aircraft was delivered to Soesterberg on 10 July 1939. Two versions were built: The G1A originally produced in series for Spain, and the larger G1B three-seat version for the Dutch airforce. In the end both types were used exclusively by the Dutch LVA. In total 62 were built.

Fokker offered Finland the G1-B machines which had been manufactured for the Spanish Air Force but Major General Lundqvist, commander of the Finnish Air Force, thought that the price was too high and delivery was suspended. After the Winter War broke out, the order was reinstituted. Fokker advised that they would be able to deliver 12 aircraft in a 4 to 5 month timeframe, with a further 6 aircraft in 6 months time. On the 2nd of February 1940, Lundqvist decided to abandon the order due to difficulty sourcing engines and propellers. The aircraft were instead sold to the Dutch Air Force.

Previous Page: 1937 Ilmavoimat Procurement Program

Next Page: 1937 – a medium Bomber for the Ilmavoimat

Return to Table of Contents for “Punainen myrsky – valkoinen kuolema” (Red Storm, White Death)

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland