Lightweight Body Armor for the Maavoimat

Reported in “The Times” London (UK), 23 October 1940. In March 1940, Sotamies (Private) Arto Luhtala survived a Soviet mortar shell landing ten feet away from him. The explosion threw him into the air, but he suffered nothing more serious than a badly bruised chest. Sotamies Luhtala told this reporter at the time that “another soldier on the same patrol stopped six burp-gun slugs with his jacket. All he got out of it was a couple of bruises.” The reason they both survived without serious injury has up until now been a military secret closely guarded by the Finnish Army – lightweight body armor for the Maavoimat of an innovative design with which most Finnish soldiers fighting on the frontlines are equipped. However, now that the Winter War is over and a Peace Treaty with the Soviet Union has been signed, this closely guarded military secret can now be revealed – and the Finnish Government has approached our military with an offer to sell the design to our Army. An offer that our Government has shamefully declined, to the disgust of this Reporter who saw how effective it was during the fighting in the Finnish Winter War. One can only surmise the reasons behind our military’s decision.”

This was the only news report on the Maavoimat’s innovative Lightweight Body Armor that saw the light of day. The Maavoimat had ensured strict censorship on foreign reporters based in Finland throughout the Winter War and no reports of this useful piece of equipment emerged during the fighting. The Reporter who wrote this short piece for The Times died in an unfortunate accident in the London Underground two days after the short article appeared in The Times. However, it can now, many years later, be revealed that the Suomen Maavoimat had in fact introduced with some success an innovative and effective Lightweight Body Armor that was widely used by their soldiers both in the Winter War, through the remainder of WW2 and into the 1950’s.

This story is a living example of the splendid cooperation, interchange of information, and integration of efforts on the part of the Maavoimat, the Finnish Forest Product manufacturers and Neste (the Finnish Oil Refining company which had branched out in the late 1930’s to include the manufacturing of Chemicals) in the development of a superior instrument of warfare. It is one in which we can all take a great deal of pride; members of the military, members of industry, and Finnish taxpayers alike. It pertains to the development and use of non-metallic body armor – a highly engineered and designed combination of wood, resin and plastics developed by a team of researchers from various Finnish forest product manufacturers over the years 1936-1938.

In the early 1930’s, the Maavoimat had begun a study of casualties in WWI, largely sourcing British and French investigations from the period of the war itself. Studies of casualties of British forces through 1916 indicated that more than three-quarters of the wounded men could have been saved if some form of armor had been worn. A large preponderance of wounds derived from fragmentation-type weapons (either shrapnel or shell fragment). Studies of French casualties showed that 60 to 80 percent of all wounds were produced by missiles of low to medium velocity.

The Maavoimat also investigated the work that had been done on WW1 body armour to protect against shrapnel or shell fragments. The British had developed a silk-lined necklet which was purported to stop a 230-grain pistol ball at 600 f.p.s. However, the primary materials, extremely difficult to obtain, had deteriorated very rapidly under combat conditions and were considered costly ($25). In addition, the British also studied a 6-pound body shield that was approximately 1 inch thick and was made of many layers of linen, cotton, and silk hardened by a resinous material. During World War I, the United States had also developed several types of armor. One, the Brewster Body Shield, was made of chrome nickel steel, weighed 40 pounds, and consisted of a breastplate and a headpiece. This armor would withstand Lewis machinegun bullets at 2,700 f.p.s. but was unduly clumsy and heavy.

The Maavoimat came up with an initial “body armor jacket” that was made up of steel plates sown into a cloth vest that hung over the shoulders to protect the chest and stomach but this was, as could be expected, rather too bulky and at 30lbs, very heavy, was incompatible with standard items of equipment, and tended to restrict the mobility of the soldier. It did stop low velocity shrapnel, but not pistol, rifle or machine-gun bullets. However, it was decided that the project should continue, albeit with a low level of funding and in 1935, the Maavoimat issued a secret research contract for the development for effective lightweight body armor for our Finnish soldiers. Our Forestry Industry responded to the challenge by putting together a team of our leading research and development scientists who accepted this challenge with zeal and determination. The willingness of these companies to pool their efforts into one single military program is indicative of the genuine spirit of cooperation developed between the military and industry in the years before the Winter War.

In May 1937, the R&D Team succeeded in laminating a mixture of fibrous wood and Bakelite in a special manner which provided encouraging ballistic values. After this initial success, the R&D Team was authorized to intensify its research program. It thoroughly investigated the bonding properties of all available resins together with the production of high-strength plywood and wood pulp mixtures, together with the best types of fabric weaves and metallic mesh to provide greater strength and lamination together with fabrication processes to provide optimum results. The end result was, by mid-1938, a wood, phenolic resin and fine metallic mesh laminate of some 20 different layers. The phenolic laminate was made by impregnating layers of different base material (in this case both a wood pulp mix similar to but far stronger than paper and silk) with phenolic resin and laminating layers of the resin-saturated base materials under heat and pressure.

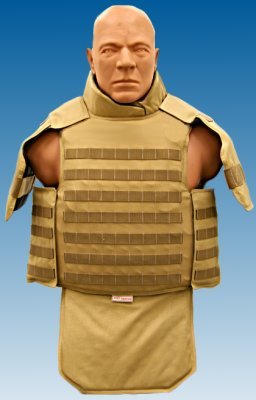

Maavoimat Body Armour – introduced on a large scale starting in 1939

The resin was fully polymerized (cured) during this process. The phenolic laminate sheets were then laminated with sheets of a thin wood-resin mix and a fine metallic (steel) mesh in multiple layers which were then pressed using 1,800 tons of heated pressure that fused everything into a super-resistant, quarter-inch-thick panel. The plates were approximately 1/4 inch thick and cut into five inch squares which were then inserted into pockets in a canvas vest that covered the front and back portions of the torso as well as the shoulders. The vest weighed approximately 8-10 pounds. The plates could be molded to fit the contours of the chest or back and the design of the vest using curved to conform with the contours of the body.

The Maavoimat reported after extensive trials: “Although tree wood may not seem like the most impenetrable defense for soldiers, when combined with resins and glues it creates a sturdy shield against exploding mortar fragments. It will not stop direct fire from rifle or machinegun bullets, but it will protect against ricochets, slow-moving shrapnel and grenade and mortar fragments.” Such was the confidence of the Maavoimat evaluation team that in a demonstration to senior officers of the GHQ, one of the team fired a .45 caliber pistol at another member of the team who was wearing the armor in order to demonstrate its effectiveness. As a result of the demonstrations and the evaluation reports, the Maavoimat ordered large scale production of the vests.

By late 1939, enough were available to equip some 50,000 Maavoimat soldiers and with the outbreak of the Winter War, production was stepped up considerably. There was never enough body armour to equip all front-line soldiers – and many soldiers did not like wearing the armor as they felt it restricted movement too much. Overall however, the body armor saved a considerable number of lives and both the military and the participating companies of the forestry and chemical industries have been more than rewarded by the knowledge that these lightweight body armor jackets returned many of our Maavoimat soldiers to their families who otherwise would have been listed “Killed in Combat.”

The Wood Fibre / Phenolic Resin / Metallic Mesh / Glue Plates which were inserted into pockets in the Canvas Vest

During the Winter War, efforts were concentrated on manufacturing the Body Armor on a large scale. After the War ended in September 1940, R&D continued and it was found that the overall strength of the laminate could be improved through the use of a thin steel plate (rather than the steel mesh previously used (to which the laminate was bonded). It also proved possible to increase the protection offered by using smaller plates (2 inches wide and circular rather than the original 5 inches and square) and overlapping these in a manner similar to old-fashioned scale armor. This was found to be far more flexible for the wearer and could absorb more damage, offering greater protection to the wearer. Tests showed that this lightweight body armor could withstand direct impacts from lower velocity rifle bullets. Although it was also far more expensive and harder to work, in 1942, this armour was put into mass production. By the time Finland entered WW2, the Maavoimat’s front-line soldiers (and many of the Allied troops now present in Finland) were fully equipped with the new “Lohikäärme Vuota” as it had come to be called.

In addition to the now-standard Chest, Back and Side protecting Vest, the laminate was used for the manufacture of lighter helmets – something that the soldiers appreciated. Additional pieces were also designed for the protection of extremities – shoulder plates, as well as neck, leg, knee, arm and elbow protectors and pieces for use in specially designed gloves. These additional pieces of protection were largely used when the Maavoimat was mounting all-out attacks and were otherwise largely carried in the Armoured Fighting Vehicles and Trucks rather than by the soldiers themselves, being issued when appropriate. The end result was that in Finland’s involvement in the war against the German Reich, Maavoimat casualties were significantly lower than those experienced by every other Army involved in the War.

The Maavoimat’s “Lohikäärme Vuota”

The combination of the Maavoimat’s superb tactical skills, outstanding weapons, Finnish Sisu and inherent aggressiveness (name another country that idolizes knife fighters if you can…) together with the sense of invulnerability given by the use of “Lohikäärme Vuota” made the Maavoimat soldiers the most feared in Europe as they charged into battle screaming the old war-cry of “Hakkaa päälle,” last heard in Germany during the Thirty Years War when the Finnish Cavalry of Gustavus Adolphus terrorized the battlefield (the alternative battle cry, generally when on the defensive, was the equally feared “Tulta munille!” which translates roughly as “Fire at their balls!”).

To the American soldiers fighting alongside the Maavoimat against Germany, the Lohikäärme Vuota armour together with their strange looking semi-automatic rifles, submachineguns, hand-held mortar-guns (aka grenade launchers) and armoured fighting vehicles made the Finnish soldiers look like something from a Buck Rogers cartoon. However, once they and the British saw how effective the Maavoimat’s equipment was, they did their level best to acquire it against the express orders of their own senior commanders (the Maavoimat of course equipped the Polish and Estonian forces fighting with them of their own accord – and later the Latvian volunteers that joined as Latvia was retaken).

To start with this led to a thriving black market, but once the Maavoimat clicked as to what was happening a decision was made that in return for hard cash (US Dollars or Pounds Sterling Kiitos), American and British soldiers were allowed to buy equipment directly from Maavoimat supply units. This had three direct results – hard foreign exchange for the Finns, lower numbers of allied casualties for the Maavoimat medical units to deal with and reduced casualties for the Allied Forces fighting under the Maavoimat’s overall command. All in all, a satisfactory outcome for all parties.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland