The 1935 Ilmavoimat Procurement Program was fairly conservative, with the first order being 40 additional Tuiska Advanced Trainers ordered from VL. With the planned buildup of the Ilmavoimat on track, and the lengthy training period required for Pilots, building up the training infrastructure needed to be addressed early and the decision to buy an additional 40 advanced trainers reflected this. An additional 24 of the Avia B-532 Fighters were also ordered. The Avia had proved itself in service and its performance surpassed that of all its competitors at the time of the order.

The Ilmavoimat also continued its search for a good modern tactical medium bomber. A wide range of bombers were evaluated through the first half of the year – many of those available were eliminated immediately as being too small, restricted in range, speed or bombload or of antiquated design. Among those that were considered were the Junkers Ju86, the designs for the Heinkel-111, the Dornier DO 13 and DO 23, the Bloch MB.200, the Potez 540, the Bristol Bombay, the Fairey Hendon, the designs for the Armstrong-Whitworth AW.23, the Handley Page Heyford, the Martin B-10, the Caproni 122 bomber and the Savoia-Marchetti SM.81.

And there was another issue that the Ilmavoimat now had to face in buying aircraft. By 1935, with the German resurgence under the leadership of Hitler, rearmament was beginning to take center stage for the major European powers and with manufacturing capacity for military aircraft having been run down in the 1920’s and early 1930’s, Germany, Britain and France in particular were focused largely on their own needs. Foreign sales were at best incidental and the Ilmavoimat’s problem was that even if an order was placed, it might be deferred or taken over right up until the last minute. Economically, Finland in 1935 had very little leverage and so a major factor in the procurement program decisions became to minimise the risk of an order being deferred, cancelled or taken over. This meant looking for aircraft that could either be licensed and manufactured in Finland (with a slow lead-time as a result) or that were available from smaller countries or from manufacturers that were not supplying aircraft and components critical to the countries own rearmament program – or the United States with its massive industrial capacity. (Incidentally, this was also a factor in the Finnish decision to set up their own aircraft engine factories – one of the major bottlenecks in aircraft manufacturing was the supply of aircraft engines – and by supplying their own engines, Finland could broaden their options somewhat going forward).

As with the 1934 transport aircraft purchase, by the middle of the third quarter of 1935 the bomber-candidate list was whittled down to a shortlist which consisted of the Martin B-10, the Caproni 122 bomber and the Savoia-Marchetti SM.81. In looking for a transport aircraft through 1934 and finally deciding on the SM.73, the Ilmavoimat Procurement Team had dealt with Savoia-Marchetti on an ongoing basis. The final decision was to purchase 15 Savoia-Marchetti SM.81s – with a large part of the decision being based on compatibility and versatility – and another large part being based on the attractiveness of the pricing (the Martin B-10 for example had a unit cost of USD$52,000 – the SM.81’s were considerably less). A further consideration was that the Italians were eager to secure export orders and rapid delivery to Finland was guaranteed personally by Mussolini, alleviating concerns on this aspect of the order. The aircraft were ordered in September 1935 and were delivered in January 1936, entering service shortly afterwards.

ilmavoimat VL Tuiska Advanced Trainers – 40 ordered in January 1935

As mentioned for the 1933 Procurement Program, an additional 40 VL Tuiska Advanced Trainers were ordered early in 1935. These were built by VL and delivered in batches over 1935 and into 1936.

Ilmavoimat Avia B-532 Biplane Fighter –24 ordered in March 1935

As mentioned for the 1934 Procurement Program, the performance of the Avia-B532 was such that 24 further aircraft of this type were ordered in July 1935. The aircraft were delivered in late 1935 and entered service almost immediately, giving the Ilmavoimat two full squadrons of this front-line fighter aircraft.

Ilmavoimat Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 – 15 ordered in September 1935

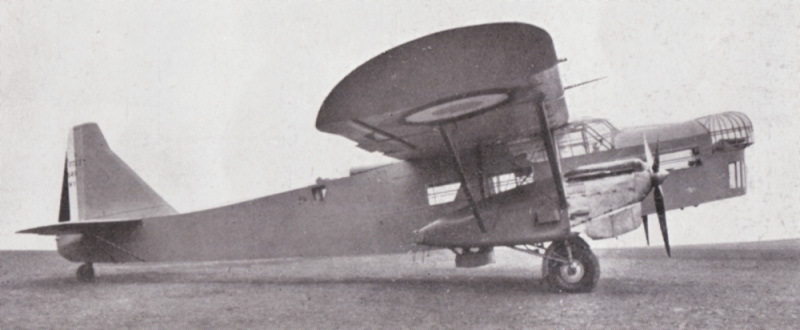

The SM.81 was a militarised version of Savoia-Marchetti’s earlier SM.73 airliner, having cantilever wings, three engines and a fixed undercarriage with the main wheels enclosed in large spats to reduce drag. The origins of this version were the need for a fast and efficient aircraft that was capable of serving in the vast Italian colonies in Africa. The SM.81 had wings that were identical to those of the SM.73, but had a much simpler fuselage. Around six months after the SM.73s first appearance, the SM.81 prototype (MM.20099) first flew on 8 February 1935, flown by test pilot Adriano Bacula. The first series ordered in 1935 was for 115 aircraft (100 for the Regia Aeronatutica, 15 for the Ilmavoimat) and was quickly put into production as a result of the international crisis and the embargo caused by the war in Ethiopia.

The SM.81 was of mixed construction: the fuselage had a framework of steel tubes with a metallic-covered aft portion, while the rest was wood- and fabric-covered – and it proved to be remarkably robust. It had a relatively large fuselage, this was an unnecessary characteristic for a bomber but derived from its civilian passenger origins – but which meant it could also make an effective transport aircraft. Since the engines were quite small in size, the fuselage did not blend well with the nose engine, even less so than with the SM.79. Many windows were present to provide the fuselage interior with light, giving the impression that it was a passenger aircraft. The aircraft had a crew of six, with the pilot and co-pilot eated side-by-side in an enclosed cockpit, with separate cabins for the flight engineer and the radio-operator/gunner behind the cockpit. The bombardier’s position was located just below the cockpit, in a semi-retractable gondola in a location which was favourable for communicating with the crew, and provided excellent visibility thanks to the glazed panel. Both this position and the cockpit had escape hatches, but for normal entry and exit there was a door in the left, mid-fuselage, and one in the aft fuselage.

The bomb bay was behind the cockpit, together with a passage which linked to the aft fuselage, where there were three further defensive positions. Equipment included an RA 350I radio-transmitter, AR5 radio-receiver, and a P63N radiocompass (not always fitted), while other systems comprised an electrical generator, fire extinguishing system, and an OMI 30 camera (in the gunner’s nacelle). The aircraft, with its large wing and robust undercarriage, proved to be reliable and pleasant to fly, and could operate from all types of terrain. It was surprisingly fast for its time, with a maximum speed of 211mph and a combat range of 1240 miles. The service ceiling was 23,000 feet and a maximum of 2,000kg of bombs could be carried. As designed, defensive armament consisted of 6 machineguns – 4 of them in two powered retractable turrets (one dorsal, just behind the pilots seats, and one ventral-aft) and 2 mounted to fire through lateral hatches. The ventral turret was operated in a different fashion to those fitted to other aircraft where the gunner occupied the ball- or dustbin-shaped structure; instead, due to lack of space, the gunner crouched in the fuselage with his head down inside the turret. This proved to be not very effective as were most ventral turrets, and they were not fitted to the Ilamvoimats SM-81s. No armour was fitted, except for the self-sealing fuel tanks.

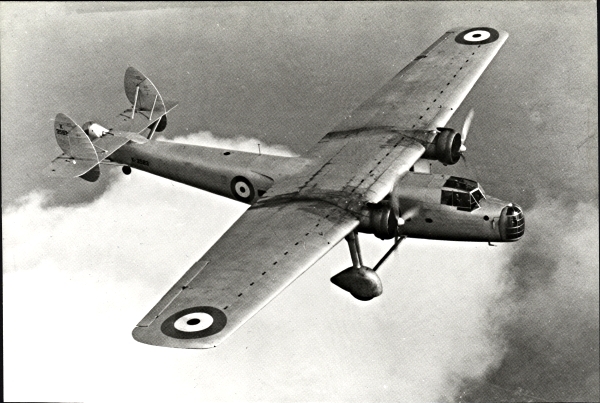

Operationally, the SM.81 first saw combat with the Regio Aeronautica during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, where it showed itself to be versatile serving as a bomber, transport and reconnaissance aircraft. SM.81s also fought in the Spanish Civil War with the Aviazione Legionaria and were among the first aircraft sent by the fascist powers to aid Franco. Ilmavoimat volunteer pilots and crew gained considerable experience in combat flying Italian-supplied SM-81s in the Spanish Civil War – combat experience that was put to good use in the Winter War. By the last stages of the Spanish Civil War, the SM.81s low speed and vulnerability to fighter aircraft meant that during daytime it was restricted to second line duties, finding use as a transport. At night the SM.81 was however still an effective bomber. Within the Ilmavoimat, this experience was incorporated into the tactical use of the SM.81s in the Winter War, where they were generally used for night-bombing and as a transport. Despite the SM.81s being obsolescent by late 1939 some 300 SM.81s were in service with the Regia Aeronautica and some 35 were sold by the Italians to the Ilmavoimat after the outbreak of the Winter War.

Finnish-volunteer flown Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 bomber during a bombing raid in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). The distinctive black crosses on the tails are the Saint Andrew’s Cross, the insignia of the Spanish Nationalist Air Force (Francos side). The accompanying Fighters are Fiat CR.32s of the “Italian” XVII Gruppo Autonomo Pohjoimaiset Sudet (“Wolves of the North”)

In hindsight, it’s interesting to look at the SM.81’s leading competitors in 1934. As mentioned previously, among those that were considered were the Junkers Ju86, the designs for the Heinkel-111, the Dornier DO 13 and DO 23, the Bloch MB.200, the Potez 540, the Bristol Bombay, the Fairey Hendon, the designs for the Armstrong-Whitworth AW.23, the Handley Page Heyford, the Martin B-10 and the Caproni 122 bomber as well as a range of other aircraft rapidly being outdated. Aircraft technology in the 1930’s was progressing rapidly and what was leading edge in one year was often second-rate by the next year and obsolete by the third. Lets take a quick look at these….

In 1934, a specification for a modern twin-engined aircraft capable of operating both as a high speed airliner for the German airline Lufthansa and as a medium bomber for the still-secret Luftwaffe was issued to both Junkers and Heinkel. Five prototypes of each of the the Junkers Ju 86 and Heinkel He 111 were ordered from each company.

The Junkers Ju86

Specs for the the Ju86R indicate a crew of 2, a maximum speed of 260mph with a range of 980 miles, a service ceiling of 42,650 feet and a 1,000kg bombload. The Ju 86 was sold to airlines and air forces from several nations, including Bolivia, Chile, Hungary, Manchukuo, Portugal, the South African Air Force (SAAF), Spain, and Sweden. The Ju 86K was an export model, also built under license in Sweden by Saab as the B 3 with (905 hp) Bristol Mercury XIX radial engines.

The Junkers design was a low-winged twin engined monoplane, of all-metal Stressed skin construction. Unlike most of Junkers previous designs, it discarded their typical corrugated skinning in favour of smooth metal skinning which helped to reduce drag. The craft was fitted with a narrow track retractable tail-wheel undercarriage and twin fins and rudders. It was intended to be powered by the Junkers Jumo 205 diesel engines, which although heavy, gave superior fuel consumption to conventional petrol engines. The bomber aircraft had a crew of four; a pilot, navigator, radio operator/bombardier and gunner. Defensive armament consisted of three machine guns, situated at the nose, at a dorsal position and within a retractable ventral position. Bombs were carried vertically in four fuselage cells behind the cockpit.

The first prototype Ju 86, the Ju 86ab1, fitted with Siemens SAM 22 radial engines as airworthy Jumo 205s were unavailable, flew on 4 November 1934, in bomber configuration, with the second prototype, also a bomber, flying in January 1935. The third Ju 86, and the first civil prototype, flew on 4 April 1935. Production of pre-series military and civil aircraft started in late 1935 with full production of the Ju 86 bomber commencing in April 1936. The bomber was field tested in the Spanish Civil War, where it proved inferior to the Heinkel He 111. In January 1940, the Luftwaffe tested the prototype Ju 86P with a longer wingspan, pressurized cabin, Jumo 207A1 turbocharged diesel engines, and a two-man crew. The Ju 86P could fly at heights of 12,000 m (39,000 ft) and higher on occasion, where it was felt to be safe from Allied fighters.

The Heinkel-111

The Ju86’s competitor within Germany was the Heinkel He 111, designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter in response to the same requirement. In 1935, comparison trials were undertaken with the He 111. At this point, the Heinkel was equipped with two BMW VI engines while Ju 86A was equipped with two Jumo 205Cs, both of which had 492 kW (660 hp). The He 111 had a slightly heavier takeoff weight of 8,220 kg (18,120 lb) compared to the Ju 86’s 8,000 kg (17,640 lb) and the maximum speed of both aircraft was 311 km/h (193 mph). However the Ju 86 had a higher cruising speed of 177 mph (285 km/h), 9 mph (14 km/h) faster than the He 111. This stalemate was altered drastically by the appearance of the DB 600C, which increased the He 111’s power by 164 kW (220 hp). In production terms the He 111 went on to dominate with 8,000 examples produced while just 846 Ju 86s were produced. The Ju 86’s weak performance could not match that of the He 111. Having dropped out of the race, Junkers concentrated on the Junkers Ju 88 design. It would be the He 111 that entered the Luftwaffe as the dominant numerical type at the beginning of the Second World War.

Heinkel He111 of the Condor Legion in Spain. Ilmavoimat volunteers had the opportunity to fly the aircraft operationally in Spain and praised its performance highly. However, despite a number of evaluations which gave the aicraft high marks, it was never purchased by the Ilmavoimat.

The first He 111 flew on 24 February 1935 and while the Ilmavoimat had rejected the civilian passenger aircraft as too small, they were interested in the bomber version. In May 1935 evaluation flights of both the Junkers Ju86 and Heinkel He111 were flown. Performance was good – a speed of 255mph, a range of 1429 miles with maximum fuel and a bomb loand of 2000kg internally (8 x 250kg bombs). However, the aircraft was still in development, delivery times could not be guaranteed and the cost as compared to the Italian SM.81 aircraft was on the high side. However the Ilmavoimat remained interested and would look at the aircraft again in 1936.

The Dornier Do13 and Do23

During the late 1920s the German Dornier Metallbauten set up a subsidiary at Altenrhein in Switzerland to build heavy aircraft expressly forbidden under the terms of the Versailles Treaty. Three aircraft were produced – The Do P, the Do Y and the Do F (a large twin) All were described as freight aircraft, but their suitability as bombers was obvious. In late 1932 it was boldly decided to put the F into production at the German factory at Friedrichshafen, and the designation was changed to Do 11. The Do 11 had a slim light-alloy fuselage, high-mounted metal wing with fabric covering carrying two 484.4kW Siemens Sh 22B engines (derived from the Bristol Jupiter), and a quaint retractable landing gear whose vertical main legs were laboriously cranked inwards along the inner wing until the large wheels lay flat inside the nacelles. There was obvious provision for a bomb bay and three gun positions. The first customer was the German State Railways which under the cover of a freight service actually enabled the embryo Luftwaffe to begin training future bomber crews.

It had been planned to deliver 372 Do 11s in 1934 but delays, plus grossly unpleasant handling and structural qualities, led to the substitution first of the short-span Do 11D and then the Do 13 with 559kW BMW VI water-cooled engines and fixed (often spatted) landing gear. At least 77 Do 11D’s were delivered, some later being passed on to another clandestine air force, that of Bulgaria.

The Do 13 was wholly unacceptable, but in September 1934 testing began of a completely redesigned machine called the Do 13e with stronger airframe, Junkers double-wing flaps and ailerons and many other changes. To erase the reputation of its forbear this was redesignated Do 23 and in March 1935 production restarted of Do 23F bombers.

No attempt was made to disguise the function of the bomber: the fuselage having a glazed nose for visual aiming of the 1,000kg bomb load housed in vertical cells in the fuselage, and nose, mid-upper and rear ventral positions each being provided with a 7.92mm MG 15 machine-gun. After building a small number the Dornier plant switched to the Do 23G with the BMW VIU engine cooled by ethylene-glycol. By late 1935 more than 200 had been delivered and these equipped the first five named Fliegergruppen – although about two-thirds of their strength comprised the distinctly preferable Ju 52/3m. Although it played a major part in the formation of the Luftwaffe and continued to the end of World War II to serve in training, trials and research roles, the Dornier Do 23 was not much better than its disappointing predecessors.

With a maximum speed of 161mph, a range of 932 miles, a service ceiling of 13,779 feet, a crew of 4 and a bomb load of 1000kg, the Dornier Do23 had a mediocre performance and at the time of the Ilmavoimat evaluation was already dated. After an evaluation that was rather cursory, it was dropped from consideration, although another Dornier aircraft, the Do17, was considered in 1936.

The Bloch MB.200

The MB.200 was a French bomber aircraft of the 1930’s designed and built by Societé des Avions Marcel Bloch in response to a 1932 requirement for a new day/night bomber to equip the French Air Force. A twin-engined high-winged all-metal monoplane with a a slab-sided fuselage and a fixed undercarriage, powered by two Gnome-Rhône 14K radial engines, over 200 MB.200s were built for the French Air Force, and the type was also licence built by Czechoslovakia. It had a fixed tail-wheel undercarriage and featured an enclosed cockpit for the pilots. Defensive machine guns were in nose and dorsal gun turrets and a under fuselage gondola.

The first of three prototypes flew on 26 June 1933. As one of the winning designs for the competition, an initial order for 30 MB.200s was placed on 1 January 1934, entering service late in that year. Further orders followed, and the MB.200 equipped 12 French squadrons by the end of 1935. Production in France totaled over 208 aircraft (4 by Bloch, 19 by Breguet, 19 by Loire, 45 by Hanriot, 10 by SNCASO and 111 by Potez. Czechoslovakia chose the MB.200 as part of a modernisation program for its air force of the mid 1930’s.

Although at the rate of aircraft development at that time, the MB.200 would quickly become obsolete, the Czechoslovakians needed a quick solution involving the license production of a proven design, as their own aircraft industry did not have sufficient development experience with such a large aircraft, or with all-metal airframes and stressed-skin construction, placing an initial order for 74 aircraft. After some delays, both Aero and Avia began license-production in 1937, with a total of about 124 built. Czechoslovakian MB.200s were basically similar to their French counterparts, with differences in defensive armament and other equipment.

With a crew of 4, the MB.200 had a maximum speed of 178mph, a range of 621 miles, a service ceiling of 26,200 feet and could carry 1200kg of bombs. The Ilmavoimat Procurement Team evaluated the aircraft and considered it already obsolete. By this time, with a good three years of experience in aircraft evaluations and with the need to keep abreast of current designs and aircraft, the team probably had a better and broader knowledge than most other Air Forces of what was available and the potential of upcoming designs. This was particularly so as they were constantly evaluating aircraft and designs from manufacturers from every major country with the exception of the USSR and Japan, as well as smaller suppliers from neutral countries such as Fokker, Avia and Aero – and indeed, they also looked at Polish aircraft.

The Potez 540

Introduced into service in 1934, this two-engine aircraft was built by the French Potez company to fulfill a 1932 specification for a new reconnaissance bomber. Built as a private venture, this aircraft, designated the Potez 54, flew for the first time on 14 November 1933. Designed by Louis Coroller, it was intended as a four-seat aircraft capable of performing duties such as bomber, transport and long-range reconnaissance. The Potez 54 was a high-wing monoplane, of mixed wood and metal covering over a steel tube frame.

The prototype had twin fins and rudders, and was powered by two 515 kW (690 hp) Hispano-Suiza 12Xbrs V-12 engines in streamlined nacelles, which were connected to the fuselage by stub wings. The main landing gear units retracted into the nacelles, and auxiliary bomb racks were mounted beneath the stub wings. There were manually-operated turrets at the nose and dorsal positions, as well as a semi-retractable dustbin-style ventral turret. During development, the original tailplane was replaced by a single fin and rudder, and in this form, the type was re-designated the Potez 540 and delivered to the Armee de I’Air on 25 November 1934. A total of 192 Potez 540s were built.

Their first combat uses was in the Spanish Civil War, where they were employed by the Spanish Republicans. In the late 1930s, these aircraft were becoming obsolete so they were withdrawn from reconnaissance and bombing duties and were relegated to French transport units. They were also employed as paratrooper training and transport aircraft. By September 1939 and the beginning of World War II, they had been largely transferred to the French colonies in North Africa, where they continued to function in transport and paratrooper service. Their role in even these secondary assignments was problematic given their poor defensive armament and vulnerability to modern enemy fighters. Following the French capitulation to Germany in June 1940, those Potez 540s still flying served the Vichy French Air Force mainly in the French overseas colonies. Most of these machines were retired or destroyed by late 1943.

With a crew of 4 of 7, the Potez 540 had a maximum speed of 193mph, a range of 777 miles and a service ceiling of 32,810 feet. They carried 4 x 225kg bombs on external racks. As with the Bloch MB.200, at the time of evaluating the aircraft in 1935, the Ilmavoimat considered the aircraft almost obsolete in design and unsuited to the tactical bombing requirements of the Ilmavoimat.

Next, we’ll take a quick look at some other aircraft that were also considered – the Bristol Bombay, Fairey Hendon, Armstrong Whitworth AW.23, Handley Page Heyford and lastly the Martin B.10.

The Bristol Bombay

The Bristol Bombay was built to British Air Ministry Specification C.26/31 for a monoplane aircraft capable of carrying bombs or 24 troops. Bristol’s early experience with monoplanes was dismal — both the 1922 racer prototype and the 1927 Bagshot fighter suffered from lack of torsional rigidity in the wings. Based on this experience, Bristol over-engineered the Bombay’s wing to include no less than seven spars made from high-strength steel. Not surprisingly, the end product was a very heavy aeroplane. The prototype Type 130 first flew on 23 June 1935 and an order for 80 was placed as the Bombay. As Bristol’s Filton factory was busy building the more urgent Blenheim, the production aircraft were built by Short & Harland of Belfast. However, the complex nature of the Bombay’s wing delayed production at Belfast, with the first Bombay not being delivered until 1939 and the last 30 being cancelled.

Despite the all-metal, monoplane construction, the Bombay retained some features which were becoming outdated by the time of the order and obsolete by delivery in 1939, such as its fixed undercarriage. Although it was outclassed for the European theatre, it saw some service ferrying supplies to the British Expeditionary Force in France in 1940. Its main service was in the Middle East, replacing the Vickers Type 264 Valentia. The Bombay was capable of dropping 250 lb (110 kg) bombs held on external racks, and was also used to drop 20 lb (20 kg) anti-personnel mines, which were armed and thrown out of the cargo door by hand. The aircraft flew bombing sorties in Abyssinia, Italian Somaliland, Iraq, and Benghazi. Obsolete as a bomber by European standards, the Bombay’s were predominately used as transports, ferrying supplies and evacuating the wounded.

The Bristol Bombay flew with a crew of 3-4 and could carry 24 armed troops or 10 stretchers. Powered by 2× Bristol Pegasus XXII radial engines of 1,010 hp (755 kW) each. It had a service ceiling of 24,850 feet and a maximum speed of 192 mph, a cruising speed of 160 mph and a range of 2,230 miles with overload fuel. The Bombay could carry 2,000 lbs of bombs and was armed with 2 × 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K machine guns in powered nose and tail turrets.

At the time of the Ilmavoimat evaluation, the Bombay prototype had just flown and the RAF order had just been placed. Evaluation flights proved that the Bombay was not as “rough field capable” as the SM-81 and in addition, its bomber role seemed to be more of an add-on to the basic transport design. The SM-81 had a better maximum speed and the long range was not as much of a consideration for the Ilmavoimat as it was for the RAF. As such, the Bombay was eliminated from consideration after the Ilmavoimat evaluation flights. However, the ongoing contacts with Bristol had also resulted in the Ilmavoimat evaluation team taking a good look at the Bristol Blenheim – more on this later….

The Fairey Hendon

The Fairey Hendon was a British monoplane heavy bomber of the Royal Air Force designed by Fairey Aviation in the late 1920’s, which served in small numbers with one Squadron of the RAF between 1936 and 1939. It was the first all-metal low-wing monoplane to enter service in the RAF. The Hendon was built to meet the Air Ministry Specification B.19/27 for a twin-engine night bomber to replace the Vickers Virginia, competing against the Handley Page Heyford and Vickers Type 150. The specification required a range of 920 mi (1,480 km) at a speed of 115 mph (185 km/h), with a bomb load of 1,500 lb (680 kg). To meet this requirement, Fairey designed a low-winged cantilever monoplane with a fixed tailwheel undercarriage. The fuselage had a steel tube structure with fabric covering and housed the crew of five, consisting of a pilot, a radio operator/navigator, and three gunners, manning open nose, dorsal and tail positions. Bombs were carried in a bomb-bay in the centre-fuselage. Variants powered by either radial engines or liquid cooled V12 engines were proposed.

The prototype K1695 (which was known as the Fairey Night Bomber until 1934 first flew on 25 November 1930, from Fairey’s Great West Aerodrome in Heathrow, and was powered by two 460 hp (340 kW) Bristol Jupiter VIII radial engines. The prototype crashed and was heavily damaged in March 1931, and so was re-built with two Rolls-Royce Kestrel engines replacing the Jupiters. After trials, 14 production examples, now named the Hendon Mk.II were ordered. These were built by Fairey’s Stockport factory in late 1936 and early 1937 and flown from Manchester’s Barton Aerodrome. Orders for a further 60 Hendons were canceled in 1936, as the prototype of the first of the next generation of British heavy bombers – the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley – had flown, and it showed much higher performance. The Hendon Mk.II was powered by two Rolls-Royce Kestrel VI engines. It had a fixed undercarriage and a crew of five while the production Hendon Mk.II included an enclosed cockpit for the pilot and navigator.

In practice, the type was delayed by the crash and rebuild of the prototype, so the Heyford received the majority of the orders needed to replace the RAF’s heavy bombers, the Hendon coming into service three years later. The single Hendon-equipped unit began operational service based in November 1936, replacing Heyfords. The type was soon obsolete and replaced from late 1938 by the Vickers Wellington. By January 1939, the Hendons had all been retired and were then used for ground instruction work, including the radio school at RAF Cranwell.

The Fairey Hendon had a crew of 5 and was powered by 2× Rolls-Royce Kestrel VI inline piston V12 engines of 600 hp (447 kW) each, giving a maximum speed of 152moh and a cruising speed of 133moh with a range of 1,360 miles. The service ceiling was 21,400 feet and a 1,660lb bombload could be carried. Armament consisted of 3× .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis guns in nose, dorsal and tail positions.

At the time of the Ilmavoimat evaluation in early 1935, the Hendon’s performance was already sadly outdated. In addition, it was a “heavy” bomber, and the Ilmavoimat’s objective was to purchase fast “medium” bombers for tactical use in support of ground operations – the antithesis of the RAF’s intent for heavy bombers. The Ilmavoimat evaluation team performed only a cursory assessment of the Hendon (as they did with a number of other such aircraft) and eliminated it from consideration immediately.

The Handley Page Heyford

The Handley Page Heyford was a twin-engine British biplane bomber of the 1930’s. Although it had a short service life, it equipped several squadrons of the RAF as one of the most important British bombers of the mid-1930’s, and was the last biplane heavy bomber to serve with the RAF. The Heyford was built to meet Air Ministry specification B.19/27 for a heavy night bomber to replace the Vickers Virginia, which required a twin-engined aircraft capable of carrying 1,546 lb (700 kg) of bombs and flying 920 miles at 115 mph (185 km/h). The specification resulted in a large number of proposals being submitted by the British aircraft industry, with designs by Fairey (the Fairey Hendon) and Vickers (the Type 150 and Type 163) being built as well as Handley Page’s design. The prototype, the Handley Page HP.38, was designed by Handley Page’s lead designer G R Volkert and first flew on 12 June 1930 at Handley Page’s factory at Radlett, powered by two 525 hp (390 kW) Rolls-Royce Kestrel II engines driving two-blade propellers.

The aircraft was of mixed construction having fabric-covered, two-bay metal-frame wings, while the fuselage had an aluminium monocoque forward section with a fabric-covered frame to the rear. It had a crew of four, consisting of a pilot, a bomb aimer / navigator / gunner a radio operator and a dorsal /ventral gunner. Open positions were provided for the pilot and both the nose and dorsal gunners. The Heyford had a novel configuration, with the fuselage attached to the upper wing and the bomb bay in the thickened centre lower wing. This provided a good defensive field of fire for the nose and dorsal guns as well as the ventral retractable “dustbin” turret, each equipped with a single .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis Gun. The fixed undercarriage consisted of large, spat-covered wheels. The design allowed ground crews to safely attach bombs while the engines were running, but the result was that the pilot was some 17 ft (5 m) off the ground.

The HP.38 proved successful during service trials and was chosen as the winner of the B19/27 competition, being ordered as the HP.50 Heyford. Production Heyford Is were fitted with 575 hp (429 kW) Kestrel III engines and retained the two-blade propellers, while the IAs had four-blade propellers. Engine variations marked the main Mk II and III differences; the former being equipped with 640 hp (480 kW) Kestrel IVs, supercharged to 695 hp (518 kW) in the Heyford III. The Heyford I entered service in November 1933, with further aircraft entering service in August 1934 and April 1935 respectively. As part of the RAF’s Expansion scheme, orders were placed for 70 Heyford IIIs in 1936, with steam condenser-cooled Rolls-Royce Kestrel VI engines. The delivery of these aircraft allowed the RAF to have nine operational Heyford Squadrons by the end of 1936. These squadrons of Heyfords formed the major part of RAF Bomber Command’s night bomber strength in the late 1930s. Heyfords flew many long night exercises, sometimes flying mock attacks against targets in France. The Heyford started to be replaced in 1937, with the arrival in service of Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys and Vickers Wellesleys, finally being retired from frontline service in 1939. They were well-liked in service, being easy to maintain, sturdy and agile and they could even be looped, as was done at the 1935 Hendon Air Pageant.

With a crew of 4 (Pilot, Navigator/bomb-aimer/forward gunner, Wireless operator/mid-upper gunner, Rear-gunner) and powered by 2× Rolls-Royce Kestrel III-S liquid-cooled V12 engines of 525 hp (392 kW) each, the Heyford had a maximum speed of 142mph, a ramge of 920 miles and a service ceiling of 21,000 feet. It could carry a 3,500lb bombload and was armed with 3 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis guns (in nose, dorsal and ventral ‘dustbin’ positions). The Heyford was introduced into service in 1934.

As with the Hendon, at the time of the Ilmavoimat evaluation in early 1935, the Heyford’s performance was already sadly outdated even though it had only just entered service. Again as with the Hendon, it was a “heavy” bomber, and the Ilmavoimat’s objective was to purchase fast “medium” bombers for tactical use in support of ground operations – the antithesis of the RAF’s intent for heavy bombers. The Ilmavoimat evaluation team performed only a cursory assessment of the Heyford (as they did with a number of other such aircraft) and eliminated it from consideration immediately.

The Armstrong-Whitworth AW.23

The Armstrong Whitworth AW.23 was a prototype bomber/transport aircraft produced to specification C.26/31 (which required a dual-purpose bomber/transport aircraft for service with the RAF, with the specification stressing the transport part of its role) for the British Air Ministry by Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft. While it was not selected to meet this specification, it did form the basis of the later Armstrong Whitworth Whitley aircraft. The AW.23 was designed by John Lloyd, chief designer of Armstrong Whitworth to meet this specification, competing with the Handley Page HP.51 and the Bristol Bombay. The AW.23 was a low-wing twin-engine monoplane, powered by two Armstrong Siddeley Tiger engines. It had a fabric covered braced steel fuselage accommodating a large cabin to fulfill its primary transport role, but with room for internal bomb racks under the cabin floor. The aircraft’s wings used a novel structure, patented by Armstrong Whitworth, which used a massive light alloy box-spar braced internally with steel tubes. This structure was extremely long but required a thick wing section, increasing drag. This wing structure was re-used in Armstrong Whitworth’s Whitley bomber. The AW.23 was the first Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft to be fitted with a retractable undercarriage.

A single prototype, K3585, was built first flying on 4 June 1935 and this was the aircraft evaluated by the Ilmavoimat. Owing to its unreliable Tiger engines, its delivery to the RAF for testing was delayed, with the Bombay being declared the winner of the specification.

With a Crew of 4, the AW.23 could carry 24 troops or 2,000 lbs of bombs. Maximum speed was 162 mph, range was 790 miles and the service ceiling was 18,100 feet. There was provision for single machine-guns in nose and tail turrets. While the Ilmavoimat evaluation team rated this aircraft considerably higher than the Hendon and the Heyford, it again failed to make the grade as far as “tactical” bombing and rough field capability was concerned. Maximum speed was also considered to be poor compared to other aircraft on the shortlist. The AW.23 was therefore eliminated from consideration.

Interestingly, the prototype would however see service in Finland. Earlier, it was mentioned that the Ilmavoimat had become aware of the in-flight refueling experiments starting to be conducted by Sir Alan Cobham at this time. By the start of 1939 these had progressed to the stage where Cobham’s company, Flight Refueling Ltd, were using the AW.23 (which they had acquired and which had been given the civil registration G-AFRX) for in-flight refueling tests with a Short Empire flying boat. And in 1939, with the threat of war from the USSR looming ever more ominously over Finland, the nascent Finnish Special Operations Command established in 1938 were looking at every option they could imagine, however wild. One of these was extending the range of the Ilmavoimat’s bombers to allow for strikes at Soviet sites of strategic vulnerability such as military factories and power plants, hydro-electric dams and other key choke-points of the Soviet economy. The Baku oilfields were also considered as a target at this stage – some 80-90% of the USSR’s oil supplies came from these fields and the vulnerability to an attack had been exposed by Neste (the Finnish Oil Company, who sourced much of their oil from these fields) engineers.

The problem was how to attack them? Baku was completely out of range of even the longest ranged Ilmavoimat bombers and thus the eyes of the Finnish Special Operations Command turned to the in-flight refueling experiments being carried out in Britain. In early 1939, the Ilmavoimat contracted Flight Refueling Ltd to work with them on evaluating and testing in-flight refueling for the newest Ilmavoimat bombers that were just coming into service. As part of this contract AW.23 G-AFRX was sent to Finland in May 1939 and the experimental program got underway. This will be covered in detail in a later post.

The Martin B-10

The Martin B-10 was the first all-metal monoplane bomber to go into regular use by the United States Army Air Corps, entering service in June 1934. It was also the first mass-produced bomber whose performance was superior to that of the Army’s pursuit aircraft of the time The B-10 began a revolution in bomber design. Its all-metal monoplane build, along with its features of closed cockpits, rotating gun turrets, retractable landing gear, internal bomb bay, and full engine cowlings, would become the standard for bomber designs worldwide for decades. It made all existing bombers completely obsolete. The B-10 began as the Martin Model 123, a private venture by the Glenn L. Martin Company of Baltimore, Maryland. It had a crew of four: pilot, copilot, nose gunner and fuselage gunner. As in previous bombers, the four crew compartments were open, but it had a number of design innovations as well included a deep belly for an internal bomb bay and retractable main landing gear.

The Model 123 first flew on 16 February 1932 and was delivered for testing to the U.S. Army on 20 March as the XB-907. After testing it was sent back to Martin for redesigning and was rebuilt as the XB-10. The XB-10 delivered to the Army had major difference from the original aircraft full engine cowlings to decrease drag, a pair of 675 hp (503 kW) Wright R-1820-19 engines, and an eight-foot increase in the wingspan, along with an enclosed nose turret. When the XB-10 flew during trials in June, it recorded a speed of 197 mph (317 km/h) at 6,000 ft (1,830 m). This was an impressive performance for 1932. Following the success of the XB-10, a number of changes were made, including reduction to a three-man crew, the addition of canopies for all crew positions, and an upgrade to 675 hp (503 kW) engines. The Army ordered 48 of these on 17 January 1933. The first 14 aircraft were designated YB-10 and delivered starting in November 1933. The production model of the XB-10, the YB-10 was very similar to its prototype.

In 1935, the Army ordered an additional 103 aircraft designated B-10B. These had only minor changes from the YB-10. Shipments began in 1935 July. In addition to conventional duties in the bomber role, some modified YB-10s and B-12As were operated for a time on large twin floats for coastal patrol. The Martin Model 139 was the export version of the Martin B-10 and with the advanced performance, the Martin company fully expected that export orders for the B-10 would come flooding in. Once the Army’s orders had been filled in 1936, Martin received permission to export Model 139’s, and delivered versions to several air forces. For example, six Model 139W’s were sold to Siam in April 1937; 20 Model 139W’s were sold to Turkey in September 1937 and aircraft went on to be sold to Argentina, China and the Netherlands.

With a Crew of 3, the B-10 was powered by 2× Wright R-1820-33 (G-102) “Cyclone” radials of 775 hp (578 kW) each giving a maximum speed of 213mph, a cruising speed of 193mph amd a range of 1240 miles with a 2,260lb bombload. Service ceiling was 24,200 feet and armament consisted of 3 × .30 in (7.62 mm) Browning machine guns.

At the time of its creation, the B-10B was so advanced that General Henry H. Arnold described it as the air power wonder of its day. It was 1.5 times as fast as any biplane bomber, and faster than any contemporary fighter. The B-10 began a revolution in bomber design; it made all existing bombers completely obsolete. However, the rapid advances in bomber design in the 1930’s meant that the B-10 was eclipsed by the B-17 Flying Fortress and Douglas B-18 Bolo before the United States entered World War II. The B-10’s obsolescence was proved by the quick defeat of B-10B squadrons by Japanese Zeros during the invasions of the Dutch East Indies and China. An abortive effort to modernize the design, the Martin Model 146 was entered into a USAAC long-distance bomber design competition 1934–1935 but lost out to the Douglas B-18 and revolutionary Boeing B-17. The sole prototype was so similar in profile and performance to the Martin B-10 series that the other more modern designs easily “ran away” with the competition.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation team rated the B-10 the best of all the aircraft they evaluated in terms of meeting the Ilmavoimat’s bomber requirement. However the cost was prohibitively high – even with increased defence budgets, the Ilmavoimat needed to keep a tight rein on expenditure. The end result was that the SM-81 was selected over the B-10. However, the many advanced features of the B-10 made their way into the Ilmavoimat’s list of requirements for future bombers, with interesting results, as we will see.

The Caproni 122 bomber

The Caproni Ca 122 was a bomber version of the Ca 123 transport that the Ilmavoimat had ordered. However, the procurement team felt that enough risk had been taken in ordering the Ca 123 transport before a prototype had even been built and the Ca 122 was thus eliminated without further consideration.

The 1935 Ilmavoimat Procurement Program in summary

In summary, over 1935, orders were placed for an additional 40 Tuiska Advanced Trainers, 24 Avia B-532 Fighters and 15 Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 bombers. All the aircraft ordered were delivered and entered service in late 1935 or early 1936.

As a result of the 1935 evaluations for a medium bomber, the Ilmavoimat Procurement Team was well aware of a range of new aircraft in the development pipeline and most of these would be evaluated in 1936, with some interesting results. The 1935 Ilmavoimat Procurement Program resulted in a successful combination of acquisitions which continued the build up pf the strength and capabilities of the Ilmavoimat, with the aircraft purchased seeing service and combat in the Winter War.

Previous Page: 1934 Ilmavoimat Procurement Program

Next Page: 1936 Ilmavoimat Procurement Program

Return to Table of Contents for “Punainen myrsky – valkoinen kuolema” (Red Storm, White Death)

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland