The plan for the 1937 procurement program made provision for the puchase of a single squadron of medium bombers for the Ilmavoimat (a further squadron was budgeted for in the 1939 program). As with other bomber purchases a strong emphasis was placed on low-altitude tactical bombing rather than “strategic” area bombing from high-altitude. Again and again Somervalo emphasised both to his “bomber” subordinates and to the General Staff that the Ilmavoimat did not have the resources to indulge in the fulfillment of unproven theories and such funding as was available should be concentrated on aircraft which could achieve accurate results, and to date that had only been achieved by low-level bombing strikes and by dive-bombing. As with other purchases over the last half of the 1930’s, the Ilmavoimat conducted a detailed evaluation and testing program – and again, this was for aircraft that were either in production or where prototypes had been completed and were undergoing testing.

As we have seen, in 1935 the Ilmavoimat had purchased 15 Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 bombers and prior to making the decision, had considered the Junkers Ju86, the designs for the Heinkel-111, the Dornier DO 13 and DO 23, the Bloch MB.200, the Potez 540, the Bristol Bombay, the Fairey Hendon, the designs for the Armstrong-Whitworth AW.23, the Handley Page Heyford, the Martin B-10 and the Caproni 122 bomber. In 1937, the Ilmavoimat was looking to purchase a further squadron of some 15-20 medium bombers and a number of the aircraft that had been only in the design stage in 1935 were looked at and evaluated as they were either available as prototypes or were actually beginning to enter production. Medium Bombers evaluated in 1937 included the Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley (UK), Bloch MB.210 (France), CANT Z.1007 (Italy), Fiat BR.20 Medium Bomber (Italy), Handley Page Hampden (UK), Heinkel He111 (Germany), Junkers Ju88 (Germany), Lioré-et-Olivier LeO 45 (France), PZL.37 Łoś (Poland), Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 (Italy) and the Vickers Wellington (UK).

Evaluation criteria heavily emphasized the ability to operate off rough airfields, good speed, manouverability and range, bombload and of course, cost and availability (with an emphasis on certainty of delivery). “Tactical” capability, as opposed to “strategic bombing” was emphasised heavily. The Ilmavoimat under the leadership of Major-General Somervalo had always emphasised support for the Maavoimat – and this was increasingly emphasised through the last half of the 1930s. Two distinct schools of aerial warfare had emerged after WW1 in the writings of air warfare theorists: tactical air warfare and strategic air warfare. Tactical air warfare was developed as part of a combined-arms attack which would be developed to a significant degree by Germany, and which contributed much to the success of the Wehrmacht during the first four years (1939–42) of World War II. The German Luftwaffe became a major element of the German blitzkrieg.

Three of the leading theorists of strategic bombing during this inter-war period were the Italian Giulio Douhet, the Trenchard school in Great Britain, and General Billy Mitchell in the USA. These theorists thought that aerial bombardment of an enemy’s homeland would be an important part of future wars. Not only would such attacks weaken the enemy by destroying important military infrastructure, they would also break the morale of the civilian population, forcing their government to capitulate. Although area bombing theorists acknowledged that measures could be taken to defend against bombers – using fighter planes and antiaircraft artillery), the maxim of the times remained “the bomber will always get through”. These theorists for strategic bombing argued that it would be necessary to develop a fleet of strategic bombers during peacetime, both to deter any potential enemy, and also in the case of a war, to be able to deliver devastating attacks on the enemy industries and cities while suffering from relatively few friendly casualties before victory was achieved.

Douhet’s proposals were hugely influential amongst most airforce enthusiasts, arguing as they did that the bombing air arm was the most important, powerful and invulnerable part of any military. He envisaged future wars as lasting a matter of a few weeks. While each opposing Army and Navy fought an inglorious holding campaign, the respective Air Forces would dismantle their enemies’ country, and if one side did not rapidly surrender, both would be so weak after the first few days that the war would effectively cease. Fighter aircraft would be relegated to spotting patrols, but would be essentially powerless to resist the mighty bombers. In support of this theory he argued for targeting of the civilian population as much as any military target, since a nation’s morale was as important a resource as its weapons. Paradoxically, he suggested that this would actually reduce total casualties, since “The time would soon come when, to put an end to horror and suffering, the people themselves, driven by the instinct of self-preservation, would rise up and demand an end to the war…” As a result of Douhet’s proposals many airforces allocated greater resources to their bomber squadrons than to their fighters, and the ‘dashing young pilots’ promoted in propaganda of the time were invariably bomber pilots.

Pre-war planners, on the whole, vastly overestimated the damage bombers could do, and underestimated the resilience of civilian populations. The speed and altitude of modern bombers, and the difficulty of hitting a target while under attack from improved ground fire and fighters which had yet to be built was not appreciated. Jingoistic national pride played a major role: for example, at a time when Germany was still disarmed and France was Britain’s only European rival, Trenchard boasted, “the French in a bombing duel would probably squeal before we did”. At the time, the expectation was any new war would be brief and very savage. A British Cabinet planning document in 1938 predicted that, if war with Germany broke out, 35% of British homes would be hit by bombs in the first three weeks. (This type of expectation should be kept in mind when considering the conduct of the European leaders who appeased Hitler in the late 1930s.). Douhet’s theories were successfully put into action in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) where RAF bombers used conventional bombs, gas bombs, and strafed forces identified as engaging in guerrilla uprisings. Arthur Harris, a young RAF squadron commander (later nicknamed “Bomber” Harris), reported after a mission in 1924, “The Arab and Kurd now know what real bombing means, in casualties and damage. They know that within 45 minutes a full-sized village can be practically wiped out and a third of its inhabitants killed or injured.”

In Finland, the Ilmavoimat under Major-General Somervalo focused on practicalities, the first of which being that while “strategic” bombing was all very good in theory, the only enemy that Finland faced was the USSR and there was absolutely no possibility that the Ilmavoimat could ever, in its wildest daydreams, build a large enough bomber fleet to conduct an effective strategic bombing campaign against one of the largest and most powerful nations in the world. The second practicality was that ongoing Ilmavoimat trials with the SM.81’s had proven to (almost) everyone’s satisfaction that Douhet’s vision of strategic bombers pounding targets to rubble was incapable of being achieved – accuracy was minimal and from high altitude there was almost no chance of hitting a specific target – in trials, less that 7% of bombs dropped hit within 1,000 feet of their aiming point. In one series of bombing tests from 15,000 feet altitude in good visibility, it took 108 bomber missions dropping 650 bombs in total to achieve 2 hits inside a 400 by 500 ft area. Empiracally, the Ilmavoimat found that very low altitude bombing resulted in very significantly improved accuracy – and that the Curtiss Helldivers and Hawker Harts used as divebombers achieved the highest accuracy (this is something that we’ll explore in a lot more detail when we get to looking at Ilmavoimat doctrine and tactics).

Consequently, in 1937 when looking for a medium bomber for the Ilmavoimat, this was where the emphasis was very strongly put. The Ilmavoimat’s bomber force was small – resources could not afford to be wasted and what was wanted was, as has been mentioned above, the ability to operate off rough airfields, good speed, maneuverability and range, bomb-load, cost and availability (with an emphasis on certainty of delivery) and a high level of “Tactical bombing” capability.

The initial shortlist for evaluation consisted of the following aircraft: Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley (UK), Bloch MB.210 (France), CANT Z.1007 (Italy), Fiat BR.20 Medium Bomber (Italy), Handley Page Hampden (UK), Heinkel He111 (Germany), Junkers Ju88 (Germany), Lioré-et-Olivier LeO 45 (France), PZL.37 Łoś (Poland), Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 (Italy) and the Vickers Wellington (UK). The B-18 Bolo and the XB-21 Dragon, both from the USA, were added to the evaluation at the manufacturers request.

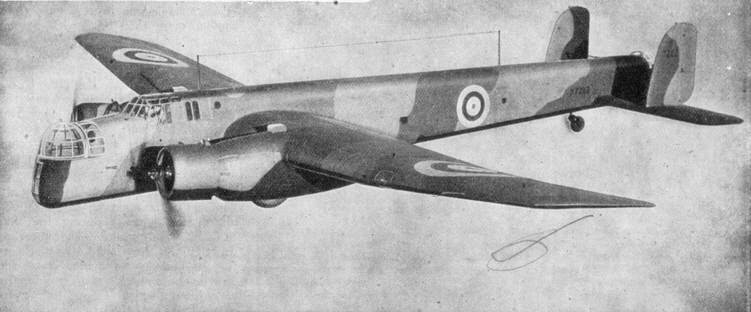

The Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley (UK)

The Armstrong Whitworth A.W.38 Whitley was one of three British twin-engine, front line medium bomber types in service with the Royal Air Force at the outbreak of WW2 (the others were the Vickers Wellington and the Handley Page Hampden). The Whitley was designed by John Lloyd, the Chief Designer of Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft to meet Air Ministry Specification B.3/34 issued in 1934 for a heavy night bomber. The Whitley carried a crew of five and was the first aircraft serving with the RAF to have a (semi ) monocoque fuselage, utilizing a slab-sided structure which eased production. As Lloyd was unfamiliar with the use of flaps on a large heavy monoplane, they were initially omitted. To compensate, the mid-set wings were set at a high angle of incidence (8.5°) to confer good takeoff and landing performance. Although flaps were included late in the design stage, the wing remained unaltered. As a result, the Whitley flew with a pronounced nose-down attitude resulting in considerable drag.

The first prototype Whitley Mk I (K4586) flew on 17 March 1936, piloted by Armstrong Whitworth’s Chief Test Pilot Alan Campbell-Orde and was powered by two 795 hp (593 kW) Armstrong Siddeley Tiger IX radial engines. The second prototype was powered by more powerful Tiger XI engines. Owing to the urgent need to replace the old and increasingly obsolete biplane heavy bombers still in service with the RAF, an order for 80 aircraft was placed in 1935, “off the drawing board,” before the Whitley had first flown. These had medium-supercharged engines and manual operated drum magazine single machine guns fore and aft. After the first 34 aircraft had been built, the engines were replaced with more reliable two-stage supercharged Tiger VIIIs, resulting in the Whitley Mk II, completing the initial order. The replacement of the manually operated nose turret with a powered Nash & Thomson turret and a powered retractable two-gun ventral “dustbin” turret resulted in the Whitley Mk III. The turret was hydraulically powered but it was hard to operate and added considerable drag.

Early marks of the Whitley had bomb bay doors – the eight bays were in fuselage compartments and wing cells – that were kept closed by bungee cords and opened by the weight of the released bombs falling on them. Even the tiny random delay in time that it took for the doors to open led to highly inaccurate bombing performance. To aim bombs, the bombardier (“Bomb Aimer” in RAF terminology) opened a hatch in the nose of the aircraft which extended the bombsight out of the fuselage. The bombardiers position was in the nose with the front gun turret above. The pilot and second pilot/navigator sat by side by side in the cockpit. The navigator rotated so that he could use the chart table behind his seat. Behind the pilots was the wireless operator. The fuselage aft of the wireless operator was divided horizontally by the bomb bay. Aft of the bomb bay was the main entrance and aft of that the rear turret. The Whitley first entered service with No. 10 Squadron in March 1937 replacing Handley Page Heyford biplanes

The Ilmavoimat evaluated the Whitley MkII in early 1937. The Whitley operated with a crew of 5 and was powered by 2 × two-stage supercharged Tiger VIII engines with a maximum speed of 230 mph, a range of 1,650 miles and a service ceiling of 26,000 feet. Armament consisted of machinegun in the nose and one in the tail. The Bomb load consisted of up to 7,000 lb (3,175 kg) of bombs in the fuselage and 14 individual cells in the wings, typically including 12 x 250lb bombs and 2 x500lb bombs. Individual bombs as heavy as 2,000lbs could be carried.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation team advised that the Whitley was designed from the start as a “night” bomber, and that it was hardly a modern looking aircraft with its slab-sided fuselage and prominent, jutting chin – and it also had a very distinctive nose-down flying attitude which added considerable drag and reduced performance. It was however, capable of carrying a very impressive bombload of 7,000lb. However, the Armstrong Siddeley Tiger engines were definitely unreliable and the defensive armament was poor. Performance was mediocre and it needed a considerable formed runway to take off. Flying the aircraft and performing tactical bombing missions at low altitude was assessed as being downright dangerous. Overall, the evaluation team rated the Whitley as completely unsuitable for use by the Ilmavoimat in the intended role.

The Bloch MB.210 (France)

The MB.210 derived from the Bloch MB.200 that the Ilmavoimat had evaluated in 1935 and differed from its predecessor by its more deeply-set, cantilever wing and its retractable undercarriage. Developed as a private venture, the prototype MB.210 completed its first flight on 23 November 1934, powered by two 596 kW (800 hp) Gnome-Rhône 14Kdrs/grs air-cooled radial engines. This was followed by a second prototype, the MB.211 Verdun, powered by 641 kW (860 hp) Hispano-Suiza 12Y V-12 liquid-cooled inlines and fitted with a retractable undercarriage, this flying on 29 August 1935. Initial flight testing of this version was somewhat disappointing, so no further examples were built. Further progress with the MB.210, however, convinced the Armée de l’Air to order series production, the first example of which flew on 12 December 1936. The satisfaction did not last very long, however, since it was underpowered and the engines of production aircraft were inclined to overheating. The type was grounded until its engines could be replaced by the more powerful and reliable Gnome-Rhône 14N, these engines first being tested in summer 1937 and had to be replaced. Altogether, 257 units were manufactured amongst companies as diverse as Les Mureaux over Potez-CAMS, Breguet, Hanriot, and Renault.

The Ilmavoimat evaluated the MB.200 as well as the MB.210 and MB.211 prototypes, but considered them no improvement on the MB.200 evaluated in 1935 – indeed, they considered them even more obsolete and ineffective than they were in 1935. The fact that the French were equipping some 12 bomber units with 250 of these already obsolete (in the opinion of the team at least) aircraft caused the Ilmavoimat evaluation team to question whether they should even look at any further French aircraft.

With a crew of 5, maximum speed of 200mph, a range of 1,056 miles, a service ceiling of 32,480 feet and a bombload of 3,520 lbs, the Bloch MB.210 was very much a design inspired by the Douhet doctrine of strategic bombing.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation team also expressed considerable concern about the ability of the French aircraft industry to delivery on any order placed. The French air force had begun a serious rearmament program in 1934 “Plan I”), which called for the production of 1,343 new aircraft. However, in the mid 1930s, the French aircraft industry was more one of scattered and disjointed complexes rather than a cohesive and capable structure. Up to forty organizations had input into nearly all aspects of aircraft design, development and production, while at the same time competing for the designated funding. As it existed in 1937, France’s aircraft industry was not structured to handle large orders and delays ere having a seriously adverse effect on the air force’s rearmament effort. Because of these organizational and structural issues, most of France’s military aircraft of the late 1930s emerged through a narrow technological window. It was a bottleneck which prevented the newly developed aircraft from achieving peak technological capability thus making them obsolete before they even reached operational status.

The problem was compounded by the type of airplanes the French government began to order. Plan I called for the construction of multirole air platforms capable of performing as bombers, fighters and reconnaissance aircraft. Instead of building dedicated platforms, the French government invested in various single type planes. Such aircraft were indeed able to carry out, on a pedestrian basis, each of the various types of missions they were called for, but they could not to distinguish themselves in any single one of them. The decision to develop such platforms was a painful compromise between the Army, the newly formed Air Force and the government. Many inside the air force believed with passion in Giulio Douhet’s strategic theory which called for the destruction of the enemy’s economic strength by destroying its infrastructure while on the other hand, the Army’s senior commanders desired that the new air force serve as a supporting force for the Army rather than as an independent force of its own.

In September 1936, France had developed a new strategic plan, Plan II. Plan II was different from its predecessor in one major area. The new Plan called for the production of up to 1,339 dedicated bombers with a complement of 756 fighters of all types. This shifting in priority towards the bomber had its roots in the new Air Minister Pierre Cot’s passion for Douhet’s strategic vision. Unfortunately for France, Plan II had no more chance of success than its predecessor. Chaos ruled in nearly all French aircraft factories. The problem was accentuated by the Popular Front’s nationalization effort of the mid to late 1930s. As a result of those two factors, France’s aircraft production actually fell during these years. In the spring of 1937, French factories were producing an average of forty units per month. This was five aircraft per month less than in 1936, the year the Germans overtook France in the total number of available airframes. Regardless of the suitability or not of the aircraft, the Ilmavoimat evaluation team expressed strong reservations about the ability of the French aircraft industry to deliver any aircraft ordered with any degree of certainty as to delivery timeframes.

The CANT Z.1007 Alcione (“Kingfisher”) (Italy)

In 1935, Filippo Zappata, the chief designer of the Cantieri Aeronautici e Navali Triestini, designed two medium bombers, the twin-engined CANT Z.1011 and the three-engined CANT Z.1007. Both were to be powered by 619 kW (830 hp) Isotta-Fraschini Asso XI.RC inline engines and were of wooden construction. The Z.1007 design was preferred by both Zappata and the Italian Aviation Ministry, with an order for 18 aircraft being placed on 9 January 1936. A further order for 16 more aircraft followed on 23 February 1937, even before a prototype had been built. It had a crew of five, consisting of two pilots, a flight engineer, a radio operator and a bombardier/navigator.

The Cant Z.1007 was developed from the Cant Z.506 seaplane, an aircraft that had established many world records in the late 1930s. It was a land-based version and incorporated many improvements, especially on the powerplant. The Z.1007 was a mid-winged monoplane with a retractable tailwheel undercarriage. It had a totally wooden structure, and a very clean shape that was much more aerodynamic than the competing SM.79. The Z.1007 had three engines, with one engine in the nose and two in the wings. The trimotor design was a common feature of Italian aircraft at the time. The aircraft had a slim fuselage as the two pilots sat in tandem rather than side-by-side as in most bombers of the period. Visibility was good and the aircraft was almost a “three-engine fighter” with a very narrow fuselage. This reduced drag, but also worsened the task of the two pilots. The aft pilot had reduced instruments and visibility, and so had difficulty flying and landing the machine if needed; he was almost an ’emergency’ pilot. Like most trimotor Italian aircraft of the period the Z.1007 suffered from poor defensive armament, poor engine reliability, and poor power to weight ratio due to low powered engines. The Z.1007 also suffered longitudinal stability problems that were partly rectified later by the adoption of a twin tail arrangement.

The Z.1007 had a defensive armament of four machine guns: two 12.7 mm (.5 in) and two 7.7 mm (.303 in). The main defensive weapon was a Caproni-Lanciani Delta manually-powered Isotta-Fraschini dorsal turret armed with a 12.7 mm (.5 in) Scotti or Breda-SAFAT machine gun. The turret had a good field of fire, although it had blind spot behind the tail. The 12.7 mm (.5 in) Breda was a standard weapon for Italian bombers and the field of fire was improved by the twin-tail configuration on later models. An electrically-powered Breda V turret carrying a similar armament was substituted in late production aircraft. Another 12.7 mm (.5 in) was in the ventral position behind the bomb bay, with a field of fire restricted to the lower rear quadrant of the aircraft. There were also two waist positions equipped with 7.7 mm (.303 in) Breda machine guns, with 500 rpg. Only one of the waist guns could be used at a time since the gunner for this position manned both guns.

The Z.1007 had a horizontal bomb bay which could carry a 1,200 kg (2,650 lb) bombload. Many other Italian aircraft had vertical bomb bays which not only limited accuracy, but also limited the size of bombs carried internally. There were also a pair of under-wing hard points which could carry up to 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) of bombs, giving the Z.1007 a potential 2,200 kg (4,900 lb) payload (to a maximum range of 640 km/400 mi), but the norm was 1,200 kg and 1,000 km range. The Z.1007’s external hardpoints were a rarity in the bombers of the Regia Aereonautica. The Z.1007 could also carry two 454 mm (17.7 in), 800 kg (1,760 lb) torpedoes slung externally under the belly in an anti-shipping role, an option which was never used in Italian service. The bombardier’s nacelle was near the wings, just below the pilot. This improved the layout compared to the SM.79, where the nacelle was almost in the tail section, with the double task of being a defence position with a machine gun mounted there.

The first prototype flew in March 1937, proving superior to the Z.1011, with its handling and manoeuvrability being praised. Its performance, however, was lower than predicted, and Zappata therefore started a major redesign of the Z.1007, production of the initial version being limited to the existing orders placed before the prototype flew. However, this was the aircraft that the Ilmavoimat evaluated. Major concerns were the poor power to weight ratio due to the low powered engines. The test pilots also expressed concerns about the longitudinal stability problems that had resulted in Zapatta beginning a redesign. These concerns were sufficient to ensure that the Ilmavoimat dropped the aircraft from further consideration.

OTL Note: After much experimentation with the prototype, the production aircraft were fitted with annular radiators so their profile was similar to radial engines that would be fitted to the improved later versions. It had “excellent flying characteristics and good stability.” Delivery of production Asso powered Z.1007s started in February 1939, with production ending in October that year. The first Asso-powered Z.1007s were used to equip the 50° Gruppo of the 16° Stormo (i.e. the 50° Gruppo of the 16° Stormo) from May 1939. The Asso powered bombers were not considered suitable for operational use, however, owing to the unreliability of their and high maintenance requirements, while their defensive armament was considered inadequate. They were therefore used as trainers.

Zappata had, meanwhile, continued the development of a considerably changed version, the Z.1007bis , to resolve the problems with the original aircraft. While the new version was of similar layout, it was effectively a completely new design. Three Piaggio P.XI RC.40 radial engines, a derivative of the French Gnome-Rhône 14K) of 736 kW (986 hp) takeoff power replaced the less powerful and unreliable liquid cooled engines of the original version. The bis was longer with wings of greater span and area, while the aircraft was considerably heavier, weighing 580 kg (1,280 lb) more unladen, with a maximum takeoff weight 888 kg (1,960 lb) greater, while it carried heavier offensive and defensive armament. The prototype bis first flew in July 1939, with testing proving successful, with the Z.1007bis being ordered into large scale production, with deliveries of pre-production aircraft starting late that year.

Italian CANT Z.1007bis Alcione bombers flying over Brindisi with course to Greece. Photo is dated March 3, 1941. Aircraft of 230 Squadron, 95th Group 35 Flock

When Italy entered World War II on 10 June 1940, the Regia Aeronautica had two Stormi equipped with the “Alcione”. One was the 16°, with 31 aircraft, equipped with the Isotta Fraschini engine and so declared “non bellici”, “not suitable for war.” The 47° Stormo had just received four CANT bis. The “Alcione” had its baptism of fire on 29 August 1940 when they began to be used for attacks on Malta, they were later involved in the attack on Greece, and then in the later stages of the Battle of Britain and after that, against Yugoslavia. Later in WW2 the Z.1007s were used mainly as night bombers and reconnaissance, they were also used for long range reconnaissance, with excellent results. Some, at least 20, were equipped with an auxiliary tank that gave 1,000 km (620 mi) extra endurance. Some were adapted for flare drops when day missions were too dangerous.

The Caproni Ca.135 (Italy)

General Valle (Chief of Staff of the Regia Aeronautica) initiated the “R-plan” – a program designed to modernize Italy’s air force, and to give it a strength of 3,000 aircraft by 1940. In late 1934 a competition was held for a bomber with the following specifications: A speed of 210 mph) at 14,800 ft and 239 mph at 16,000 ft), a range: of 620 miles with a 2,600 lb bombload and a ceiling of 26,000 feet. The ceiling and range specifications were not met, but the speed was exceeded by almost all the machines entered. At the end of the competition, the “winners” were the Ca.135 (with 204 aircraft ordered), the Fiat BR.20 (204 aircraft ordered), the Piaggio P.32 (144 aircraft ordered), the Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 (96 ordered), the CANT Z.1007 (49 ordered), and the Piaggio P.32 (12 ordered). This array of aircraft was proof of the anarchy, clientelarism, and inefficiency that afflicted the Italian aviation industry. Worse was the continuous waste of resources by the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Royal Air Force). Orders were given for aircraft that were already obsolete. The winners of the competition were not always the best – the BR.20 was overlooked in favour of the SM.79, an aircraft which was not even entered in the competition.

The Caproni Ca.135 itself was an Italian medium bomber designed by Cesare Pallavicino of CAB (Caproni Aereonautica Bergamasca). The Ca.135 was to be built at Caproni’s main Taliedo factory in Milan. However, the project was retained at Ponte San Pietro and the prototype, completed over 1934-35, (a long construction time for the period), was first flown on 1 April 1935. The new bomber resembled the Caproni Ca.310, with its rounded nose, two engines, low-slung fuselage and wings with a very long chord. Several versions were fitted with different engines and some had noticeable performance differences. The prototype was powered by two 623 kW (835 hp) (at 4,000 m/13,123 ft) Isotta-Fraschini Asso XI.RC radial engines initially fitted with two bladed wooden propellers. Structurally, it was built of mixed materials, with a stressed-skin forward fuselage and a wood and fabric-covered steel-tube rear section; the wings being of metal and wood, using fabric and wood as a covering. The wings were more than ⅓ of the total length, and had two spars of wooden construction, covered with plywood and metal. The tail surfaces were built of wood covered with metal and plywood. The fuel system, with two tanks in the inner wings, held a total of 2,200 L (581 US gal).

The Ca.135’s fuselage shape was quite different from, for example, that of the Fiat BR.20. If the latter resembled the American B-25 Mitchell, the Ca.135, with its low fuselage more resembled the American B-26 Marauder. Its long nose accommodated the bomb-aimer (bombardier) and a front turret (similar to the Piaggio P.108 and later British bombers). The front part of the nose was detachable to allow a quick exit from the aircraft. It also had two doors in the cockpit roof, giving the pilots the chance to escape in an emergency. The right-hand seat could fold up to assist entry to the nose. A single 12.7 mm (0.5 in) machinegun in a turret in mid-fuselage, was manned by the co-pilot. A seat for the flight engineer was later fitted. The wireless operator’s station, in the aft fuselage, was fitted with the AR350/AR5 (the standard for Italian bombers), a radiogoniometer (P63N), an OMI AGR.90 photographic-planimetric machine or the similar AGR 61. The aircraft was also equipped with an APR 3 camera which although not fixed, was normally operated through a small window. The wireless operator also had a 12.7 mm (0.5 in) machine gun in the ventral position. All this equipment made him very busy; as a result, an extra man was often carried. The aircraft had very wide glazed surfaces in the nose, cockpit, and the central and aft fuselage; much more than in other Italian aircraft.

Overall, the aircraft was fitted with three machine guns, of 12.7 mm (0.5 in) calibre in the turrets, and a 7.7 mm (0.303 in) calibre gun in the nose. All had 500 rounds, except the 7.7 mm (0.303 in) which had 350. Bombload, like most Italian bombers, was less than impressive in terms of total weight, but was relatively flexible, depending on the role – from anti-ship to close air support and a maximum 4,105lb bombload could be carried – or alternatively 2 × torpedoes (never used, but hardpoints were fitted). The aircraft was underpowered, with a maximum speed of 226 mph at 14,800 ft and a high minimum speed of 81 mph (there were no slats, and maybe not even flaps). The Service Ceiling was only 20,000 ft and the endurance, at 70% of throttle, was 990 miles. All-up weight was too high, with total of 819,240 lb, not the 16,260 lb expected.

The total payload was shared between the crew, weapons, radios and other equipment, fuel, oil, oxygen and bombs. There was almost no chance of carrying a full load of fuel with the maximum bombload. The lack of power made take-offs when over-loaded, impossible. Indeed, even with a normal load, take-offs were problematic. Take-off and landing distances were 418 m (1,371 ft) and 430 m (1,410 ft). The range was good enough to assure 2,200 km (1,400 mi) with 550 kg (1,210 lb) and 1,200 km (750 mi) with 1,200 kg (2,650 lb). The early production version was fitted with two inline liquid-cooled Asso XI RC.40 engines, each giving 671 kW (900 hp) at 4,000 m (13,120 ft). Aerodynamic drag was reduced, with three-bladed metal propellers that were theoretically more efficient. These new engines gave the aircraft a maximum speed of 400 km/h (250 mph) at 4,000 m (13,120 ft). It could climb to 2,000 m (6,560 ft) in 5.5 minutes, 4,000 m (13,120 ft) in 12.1 minutes and 5,000 m (16,400 ft) in 16.9 minutes.

Despite this, the aircraft was still underpowered. The aircraft evaluated by the Ilmavoimat yawed to the right on take-off, had poor lateral stability; the engines (from comments made by the Italian pilots) were unreliable in service, and the bombers suffered a excessive number of oil and hydraulic leaks during testing. The Ca 135 was also assessed as being dangerously underpowered and lacking in defensive armament. As a result, the test team made strong recommendations against this aircraft.

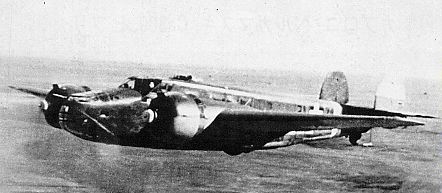

The Douglas B-18 Bolo (USA)

In 1934, the United States Army Air Corps put out a request for a bomber with double the bomb load and range of the Martin B-10, which was just entering service as the Army’s standard bomber. In the evaluation at Wright Field the following year, Douglas showed its DB-1. It competed with the Boeing Model 299 (later the B-17 Flying Fortress) and Martin Model 146. While the Boeing design was clearly superior, the crash of the B-17 prototype (caused by taking off with the controls locked) removed it from consideration.

During the depths of the Great Depression, the lower price of the DB-1 ($58,500 vs. $99,620 for the Model 299) also counted in its favor. The Douglas design was ordered into immediate production in January 1936 as the B-18. The initial contract called for 133 B-18s (including DB-1), using Wright R-1820 radial engines. The last B-18 of the run, designated DB-2 by the company, had a power-operated nose turret. This design did not become standard. An additional contract was placed in 1937 for a further 177 aircraft.

One thing that was evident to the Ilmavoimat Team was that Douglas would certainly be able to fulfill any orders placed. The manufacturing facilities were impressive!

The DB-1 design was essentially that of the DC-2, with several modifications. The wingspan was 4.5 ft (1.4 m) greater. The fuselage was deeper, to better accommodate bombs and the six-member crew; the wings were fixed in the middle of the cross-section rather than to the bottom, but this was due to the deeper fuselage. Added armament included nose, dorsal, and ventral gun turrets. Production B-18s, with full military equipment fitted, had a maximum speed of 217 mph, cruising speed of 167 mph, and combat range of 850 miles. The Bolo carried a 4,400lb bombload and was armed with 3 × .30 in (7.62 mm) machine guns.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation team considered the Bolo soundly designed and built but underpowered, carrying too small a bomb load and with limited defensive armament. The aircraft remained in consideration however.

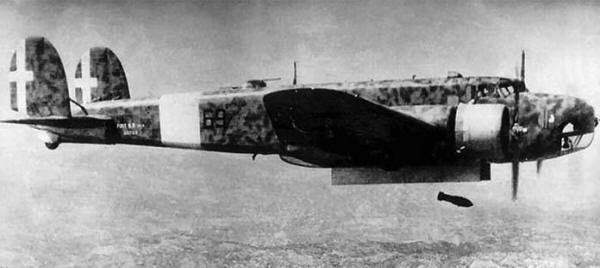

The Fiat BR.20 Medium Bomber (Italy)

In 1934, Regia Aeronautica requested Italian aviation manufacturers to submit proposals for a new medium bomber; the specifications called for speeds of 330 km/h (205 mph) at 4,500 m (15,000 ft) and 385 km/h (239 mph) at 5,000 m (16,400 ft), a 1,000 km (620 mi) range and 1,200 kg (2,600 lb) bombload. Although Piaggio, Macchi, Breda, Caproni and Fiat offered aircraft that mainly exceeded the speed requirements (but not range), not all exhibited satisfactory flight characteristics or reliability. Accepted among the successful proposals, together with the trimotor Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 and Cant Z.1007, was the Fiat BR.20 Cicogna designed by Celestino Rosatelli, thus gaining the prefix BR, (for “Bombardiere Rosatelli”). The BR.20 was designed and developed quickly, with the design being finalised in 1935 and the first prototype (serial number M.M.274) flown at Turin on 10 February 1936. Production orders were quickly placed, initial deliveries being made to the Regia Aeronautica in September 1936. When it entered service in 1936 it was the first all-metal Italian bomber and it was regarded as one of the most modern medium bombers available anywhere.

The BR.20 was a twin-engine low-wing monoplane, with a twin tail and a nose separated into cockpit and navigator stations. Its robust main structure was of mixed-construction; with a slab-sided fuselage of welded steel tube structure having duralumin skinning of the forward and centre fuselage, and fabric covering the rear fuselage. The 74 m² (796 ft²) metal-skinned wings had two spars and 50 ribs (also made of duralumin), with fabric-covered control surfaces. The hydraulically actuated main undercarriage elements retracted into the engine’s nacelles, and carried 106 x 375 x 406 mm wheels. The takeoff and landing distances were quite short due to the low wing loading, while the thickness of the wing did not compromise the aircraft’s speed. The twin tail allowed a good field of fire from the dorsal gun turret.

The engines were two Fiat A.80 RC 41s, rated at 1,000 cv at 4,100 m (13,451 ft), driving three-blade Fiat-Hamilton metal variable-pitch propellers. Six self-sealing fuel tanks in the centre fuselage and inner wings held 3,622 Ls of fuel, with two oil tanks holding 112 L. This gave the fully-loaded bomber, (carrying a 7,900 lb payload) an endurance of 5½ hours at 350 km/h (220 mph), and 16,400 ft altitude. Takeoff and landing distances were 350 m (1,150 ft) and 380 m (1,250 ft) respectively. The theoretical ceiling was 24,930 ft. Crewed by four or five, the BR.20’s two pilots sat side-by-side with the engineer/radio operator/gunner behind. The radio operator’s equipment included an R.A. 350-I radio-transmitter, A.R.5 receiver and P.3N radio compass. The navigator/bomb-aimer had a station in the nose equipped with bombsights and a vertical camera. Another two or three crewmembers occupied the nose and the mid-fuselage, as radio-operator, navigator and gunners. The radio operator was also the ventral gunner while the last crew member was the dorsal gunner.

The aircraft was fitted with a Breda model H nose turret carrying a single 7.7 mm (.303 in) Breda-SAFAT machine gun, and was initially fitted with a Breda DR dorsal turret carrying one or two 7.7 mm (.303 in) machine guns. This turret was unusual because it was semi-retractable: the gunner’s view was from a small cupola, and in case of danger, he could extend the turret. The aircraft was fitted with a further 7.7 mm (.303 in) machine gun in a ventral clamshell hatch that could be opened when required. The BR.20’s payload was carried entirely in the bomb bay in any of the following possible combinations: 2 × 800 kg (1,760 lb) bombs as maximum load, 2 × 500 kg (1,100 lb), 4 × 250 kg (550 lb), 4 × 160 kg (350 lb), 12 × 100 kg (220 lb), 12 × 50 kg (110 lb), 12 × 20 kg (40 lb), or 12 × 15 kg (30 lb) bombs. Combinations of different types were also possible, including 1 × 800 kg (1,760 lb) and 6 × 100 kg (220 lb), 1 × 800 kg (1,760 lb) and 6 × 15 or 20 kg (30 or 40 lb), or 2 × 250 kg (550 lb) and 6 × 50 or 100 kg (110 or 220 lb) bombs. The BR.20 could also carry four dispensers, armed with up to 720 × 1 or 2 kg (2 or 4 lb) HE or incendiary bomblets. All the bombs were loaded and released horizontally, improving the accuracy of the launch.

With a Crew of 5, the BR.20 was powered by 2 × Fiat A.80 RC.41 18-cylinder radial engines of 746 kW (1,000 hp) each giving a maximum speed of 273mph, a range of 1,709 miles and a service ceiling of 26,250 feet. Defensive armament consisted of 3× 12.7 mm (.5 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns in nose, dorsal and ventral positions. A 3,530lb bombload could be carried.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation team considered the BR.20 a remarkably good aircraft that could be improved somewhat by increased engine power and heavier armament. They recommended that consideration be given to a gunship ground attack version fitted with nose-mounted cannon, a tricycle undercarriage and armour protection for the crew – and as with the Polish PZL 37, they considered that for Ilmavoimat use, 2 crew positions could be eliminated – the ventral gunner and the bombardier / nose gunner.

The Handley Page Hampden (UK)

The Handley Page HP.52 Hampden was a British twin-engine medium bomber designed or the RAF to the same specification as the Wellington (Air Ministry Specification B.9/32). The first production batch of 180 Mk I Hampdens was built to Specification 30/36. Conceived as a fast, manoeuvrable, “fighting bomber”, the Hampden had a fixed .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K machine gun in the forward fuselage. To avoid the weight penalties of powered-turrets, the Hampden had a curved Perspex nose fitted with a manual .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K gun and two more single .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K installations in the rear upper and lower positions. The layout was similar to the all-guns-forward cockpits introduced about the same time in the Luftwaffe’s medium bombers, notably the Dornier Do 17.

Construction was from sections prefabricated then joined. The fuselage was in three major sections – front, centre and rear. The centre and rear sections were themselves made of two halves. This meant the sections could be fitted out in part in better working conditions before assembly. In a similar way, the wings were made up of three large units – centre section, port outer wing and starboard outer wing – which were in turn sub-divided. The Hampden was a stressed skin design reinforced with a mixture of bent and extruded sections. The wing used a single main spar. The first prototype flew on 21 June 1936. Crewspace was cramped and there were a number of blindspots in the defense. Due to the short and narrow fuselage and long tail boom it was soon nicknamed “Flying Suitcase.”

With a Crew of 4 (Pilot, navigator/bomb aimer, radio operator and rear gunner), the Hampden was powered by 2 × Bristol Pegasus XVIII 9-cylinder radial engines of 980 hp (730 kW) each giving a maximum speed of 265mph, a range of 1,095 miles and a service ceiling of 19,000 feet. Defensive armament consisted of 4-6 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K machine guns: one flexible and one fixed in the nose, one or two each in the dorsal and ventral positions. A maximum 4,000lb bombload or 1 Torpedo could be carried.

The Ilmavoimat assessment was that the aircraft had some good features, but quite a few bad ones. It had good visibility and light controls. Until you got rudder lock if you inadvertently got into a side-slip. Ailerons wouldn’t get you out. When the fuel was low the engines would quite if you made a skidding turn. And the fuel selectors were controlled from the rear by the radio operator. As the Ilmavoimat Test Pilot commented, “Definitely NOT good.” On the other hand, at 10,000 feet it had about a ten hour range at an indicated 150mph. It had an autopilot using electric, pneumatic and hydraulic power – and a built in tail-wheel shimmy, lacking a positive lock.

The Pegasus XVIII engines were said to be reliable. But both big cowl gill installations were controlled by one hand crank. So if you lost one engine and had to pull power out of the good one and it heated up, you had double drag. The props were non-feathering – more drag. It had one hydraulic pump and one generator on the right engine, so make sure to lose the left. The brakes were the usual British differential pneumatic type, controlled by the right thumb on the pilot’s control wheel. But it had two – not one – flap indicators, and the starboard flap came down faster that the port.

The Ilmavoimat Test Pilot expressed the rather pointed view that a madman had designed the landing gear and flap controls. They were hidden away in a tin box with a spring-loaded lid, the scars from which the Test Pilot carried on his right hand to his dying day. The test pilot’s notes in their usual understated way described what happened when you had an engine failure in flight as follows: “height can be maintained at light load with gills closed and flaps up. At heavy load, height will be lost slowly, but by jettisoning bombs and the reduction of weight with the consumption of fuel, a considerable distance can be covered.” In other words, the Hampden couldn’t fly on one engine.

OTL Note: A total of 1,430 Hampdens were built: 500 by Handley Page, 770 by English Electric at Samlesbury in Lancashire; and in 1940–41, 160 in Canada by the Canadian Associated Aircraft consortium (although some were retained in Canada, 84 were shipped by sea to the United Kingdom). The Hampden wasn’t good at daylight bombing as it had many blind spots for defense and the crew was very cramped in the narrow confines (3 feet wide at the widest point) of the fuselage. It proved to have a totally inadequate defensive armament. Heavy losses were suffered on day bomber missions. The Hampden was abandoned by RAF Bomber Command in 1942. Some were then converted to torpedo bombers.

The Heinkel He111 (Germany)

The Heinkel He 111 had been designed earlier in the 1930’s by Siegfried and Walter Günter. The first He 111 flew on 24 February 1935 and while the Ilmavoimat had rejected the civilian passenger aircraft as too small for the military transport they were then looking for, they were interested in the bomber version. In May 1935 evaluation flights of both the Junkers Ju86 and Heinkel He111 had been flown. Performance of the He111 was good – a speed of 255mph, a range of 1429 miles with maximum fuel and a bomb load of 2000kg internally (8 x 250kg bombs). However, the aircraft was still in development, delivery times could not be guaranteed and the cost as compared to the Italian SM.81 aircraft that in the end was selected as a bomber (in 1935) was on the high side. However the Ilmavoimat remained interested and in 1937 they re-evaluated the aircraft.

In 1935, when the Ilmavoimat had first evaluated the aircraft, the Heinkel was equipped with two BMW VI engines and the maximum speed was 311 km/h (193 mph). By early 1937, a number of prototypes with increasingly more powerful engines and better wing designs had been built – the Ilmavoimat at this stage tested a military bomber variant – the He111B-1. The bomb load was now 1,500 kg (3,300 lb), while there was also an increase in maximum speed and altitude to 215 mph (344 km/h) and 22,000 ft and the armament settled at three machine gun positions. Construction had begun at the Heinkel factory at Oranienburg and Heinkel assured the Finns that any order they placed could be met (mentioning also that the Turkish Air Force were negotiating to buy a number of the aircraft). The evaluation team rated the He111 highly.

With a Crew of 4 (pilot, navigator/bombardier/nose gunner, ventral gunner, dorsal gunner/radio operator), the He111 had a maximum speed of 215mph, could carry a 3,300lb bombload with a range of 1,429 miles and had a service ceiling of 22,000 feet.

Heinkel He111 of the Condor Legion in Spain. Ilmavoimat volunteers went on to fly the aircraft operationally in Spain and praised its performance highly. However, despite the 1935 amd 1937 evaluations which gave the aicraft high marks, it was never purchased by the Ilmavoimat

The Junkers Ju88 (Germany)

In August 1935, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium submitted its requirements for an unarmed, three-seat, high-speed bomber, with a payload of 800-1,000 kg (1,760-2,200 lb). Junkers presented their initial design in June 1936, and were given clearance to build two prototypes (Werknummer 4941 and 4942). The first two aircraft were to have a range of 2,000 km (1,240 mi) and were to be powered by two DB 600s. Three further aircraft, (Werknummer 4943, 4944 and 4945), were to be powered by Jumo 211 engines. The first two prototypes, Ju 88 V1 and V2, were different from the V3, V4 and V5 in that the latter three models were equipped with three defensive armament positions to the rear of the cockpit, and were able to carry two 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) bombs under the inner wing.

First of the many, the Ju88V1 of 1936 carrying the civil registration D-QEN. This machine soon crashed and was replaced in the test programme by the generally similar V2, D-AREN, first flown on 10 April 1937.

The first five prototypes had conventionally-operating dual-strut leg rearwards-retracting main gear, but starting with the V6 prototype, a main gear design that twisted the new, single-leg main gear strut through 90° during the retraction sequence debuted, much like the American Curtiss P-40 fighter design used. This feature allowed the main wheels to end up above the lower end of the strut when fully retracted [N 1] and was adopted as standard for all future production Ju 88s, and only minimally modified for the later Ju 188 and 388 developments of it. These single-leg landing gear struts also made use of stacks of conical Belleville washers inside them, as their main form of suspension for takeoffs and landings.

The aircraft’s first flight was made by the prototype Ju 88 V1, which bore the civil registration D-AQEN, on 21 December 1936. When it first flew, it managed about 580 km/h (360 mph) and Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe was ecstatic. It was an aircraft that could finally fulfill the promise of the Schnellbomber, a high-speed bomber. The streamlined fuselage was modeled after its contemporary, the Dornier Do 17, but with fewer defensive guns because the belief still held that a high speed bomber could outrun late 1930s-era fighters. However, production was delayed drastically with developmental problems and this was the situation when the Ilmavoimat assessed the prototype in early 1937.

At this stage, the Ilmavoimat team liked the aircraft and could see its potential with its projected bombload of 6,600lb and a speed of 300mph+. However, with the problems still being worked on, a number of prototypes in development and production not yet in sight, the team recommended a “wait and see” approach with a further evaluation to be carried out in 1938.

The Lioré-et-Olivier LeO 45 (France)

The Lioré-et-Olivier LeO 45 was a French medium bomber designed and built as a low-wing monoplane, all metal in construction, equipped with a retractable undercarriage and powered by two 1,100 hp Hispano-Suiza engines. It was conceived as a second-generation strategic bomber for the French Air Force. In contrast to its predecessors which relied on machine guns for protection, the emphasis was placed on a high-speed high-altitude bomber design. The expectation was that high speed would force enemy fighters into tail-chase attacks and to that effect the aircraft was designed with a rear-firing defensive cannon with an unobstructed rear arc of fire thanks to the twin rudders. The Service Technique Aéronautique released the initial requirements on 17 November 1934, specifying a 5-seat bomber with a top speed of 400 km/h (215 knots, 250 mph) at 4,000 m (13,125 ft), and a combat radius of 700 km (435 mi) carrying a payload of 1,200 kg (2,650 lb). In September 1936, the requirements were revised to account for development of 1,000 hp (746 kW)-class engines, with cruise speed raised to 470 km/h (255 knots, 290 mph) and crew reduced to four. The French Air Force’s Plan II called for 984 of the resulting B4-class bombers.

Numerous manufacturers submitted a proposal, including Latécoère, Amiot with its Amiot 351, and Lioré et Olivier, which was to be soon nationalized as part of the SNCASE. Lioré et Olivier was a long-time purveyor to the Armée de l’air with its LeO 20 and other lesser-known biplane bombers that had earned a reputation for reliability, but were very traditional in design. The 1934 programme required modern solutions, and consequently the company management put a younger engineer, Pierre Mercier, who had expertise in cantilever airframes, at the helm of the design team. Mercier’s work resulted in a design, christened the LeO 45, of a twin-engined aircraft of all-metal construction with a monocoque fuselage. Because of the speed requirements of the programme, a lot of effort was spent in reducing parasitic drag. Wings were equipped with slotted flaps and small bomb bays in the wing roots in addition to the main fuselage bomb bay, so as to limit the fuselage’s cross-section. A new wing structure was designed and patented by Mercier, where the inner part used two spars, with enough room between them for a 200 kg-class bomb and large self-sealing fuel tanks. However the spars didn’t go all the way to the wing-tip, but made way for a box-type structure at the tips.

Mercier also used his patented type of fairing for the LeO 45’s radial engines. Unlike typical NACA cowlings, flow adjustment was not provided by flaps, but by a frontal ring that moved back and forth to respectively reduce or increase flow, without change in drag. Like many other French twin-engine planes of the era, propellers rotated in the opposite directions to eliminate the undesirable effects of propeller torque. The undercarriage was fully retractable, with an unusually complicated mechanism for the main wheels in order to reduce the size of the engine nacelles. The fuselage hosted the four-man crew in the following order: the bombardier, who was also the commander as per French tradition, sat in the glazed nose ahead of the pilot. Immediately behind the pilot, the radio operator could man a defensive 7.5 mm M.1934 (500 rounds) machine gun from an underbelly retractable “gondola”. A corridor alongside the main bomb bay led to the rear gunner’s position which featured a powered mounting for the required 20 mm cannon. This was a really powerful cannon, the Hispano-Suiza HS.404, with 120 rounds, and excellent ballistic proprierties (over 800 m/s), well above MG FF and other Oerlikon guns. The turret was retraclable when not needed. The armament was completed with another 7.5 mm machine-gun M.1934/39, this time in the nose (300 rds).

Overall, the Leo’s bombload was up to seven 200 kg bombs, or other combinations (up to a maximum of 1-2 500 kg bombs in the fuselage bomb bay, plus the two 200 kg bombs in the wings). The maximum bombload penalized fuel capacity, which was reduced to only 1,000 lts. The fuel tanks were: two 880 lts (inner wings), two 330 and two 410 lts (all in the external wings). The LeO 45-01 prototype, powered by a pair of Hispano-Suiza 14Aa 6/7 radial engines producing 1,120 hp (835 kW) each flew for the first time on 16 January 1937. Despite problems with longitudinal instability, and engine reliability and overheating, the aircraft demonstrated excellent performance, reaching 480 km/h (300 mph) at 4000 m, and attaining 624 km/h (337 knots, 388 mph) in a shallow dive. (Well after the Ilmavoimat evaluation, in July 1938, the prototype fitted with the new Mercier cowlings reached 500 km/h (270 knots, 311 mph). Subsequently, the troublesome Hispano-Suiza engines were replaced with Gnome-Rhone 14N 20/21 engines producing 1,030 hp (768 kW) each, and the aircraft was redesignated LeO 451-01.

The 16th Paris Air Show, in 1938, showed planes such as the prototype of the Lioré et Olivier LeO 45, shown here

With a Crew of 4, the prototype evaluated by the ilmavoimat was powered by two Hispano-Suiza 14Aa 6/7 radial engines producing 1,120 hp (835 kW) each and giving a maximum speed of 300mph, with a range of 1,800 miles and a service ceiling of 29,530 feet. Maximum bombload was 3,457lbs and defensive armament consisted of 1 cannon and 2 machineguns.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation team liked the aircraft’s handling but expressed concerns regarding the limited range with a maximum bombload as well as the engine reliability issue. As with the Bloch MB.210, the team also expressed considerable concern about the ability of the French aircraft industry to delivery on any order placed (a well-founded concern as it turned out). This was especially frustrating as a large loan for purchases of military equipment had been made to Finland by the French government in 1937.

OTL Note: As the international situation was worsening, the Armée de l’Air ordered the LeO 451, explicitly asking SNCASE not to delay production with further improvements, even though teething troubles were far from cleared. The first production LeO 451 was built in 1938. The decision to abandon Hispano-Suiza engines and a shortage of propellers resulted in production delays. The latter also caused most aircraft to be fitted with slower Ratier propellers which reduced the top speed from 500 to 480 km/h. As the result, although 749 LeO 451 had been ordered, only 22 were delivered by the start of World War II. Of these, only 10 were formally accepted by the Air Force. They were issued to a frontline unit tasked with experimenting the new type in the field, and flew a few reconnaissance flights over Germany, which resulted in the type’s first combat loss. At the start of the Battle of France on 10 May 1940, only 54 of the 222 LeO 451 that had been delivered were considered ready for combat, the remainder being used for training, spares, undergoing modifications and repairs or having been lost.

The first combat sortie of the campaign was flown by 10 aircraft from GB I/12 and GB II/12 on 11 May. Flying at low altitude, the bombers suffered from heavy ground fire with one aircraft shot down and 8 heavily damaged. Within the next 8 days many of them were shot down, like the one piloted by sergent-chef Hervé Bougault near Floyon during a bombing mission over German troops. By the Armistice of 25 June 1940, LeO 451 of the Groupement 6 had flown approximately 400 combat missions, dropping 320 tons of bombs at the expense of 31 aircraft shot down by enemy fire, 40 written off due to damage, and 5 lost in accidents. It was an effective bomber, but it appeared too late to give any substantial contribution to the war effort. Although designed before World War II, it remained in service until September 1957.

The North American Aviation XB-21 Dragon (USA)

The North American XB-21, also known by the manufacturer’s model designation NA-21, and sometimes referred to by the name “Dragon”, was a prototype bomber aircraft developed by North American Aviation in the late 1930’s, for evaluation by the United States Army Air Corps. North American Aviation’s first twin-engined military aircraft, the NA-21 prototype was constructed at North American’s factory in Inglewood, California, where work on the aircraft began in early 1936. The NA-21 was a mid-wing monoplane of all-metal construction, powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-2180 Twin Hornet radial engines, which were fitted with turbo-superchargers for increased high-altitude performance. Flown by a crew of six to eight men, the XB-21 featured a remarkably strong defensive armament for the time, including as many as five .30-calibre M1919 machine guns. These were planned to be fitted in hydraulically powered nose and dorsal turrets, in addition to manually operated weapons installed in waist and ventral positions. Up to 10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) of bombs could be carried in an internal bomb bay, with 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg) of bombs being able to be carried over a range of 1,900 miles (3,100 km).

The XB-21 flew for the first time on December 22 1936 at Mines Field, with company test flying indicated a number of minor problems. Modifications resolving these resulted in the aircraft being re-designated NA-39, and, accepted by the U.S. Army Air Corps as the XB-21. The aircraft, which had been assigned the serial number 38-485, was evaluated early in 1937 in competition against a similar design by Douglas Aircraft, an improved version of the company’s successful B-18 Bolo. During the course of the fly-off, the gun turrets proved troublesome, their drive motors proving to be underpowered, and issues with wind blast through the gun slots were also encountered. As a result of these problems, the XB-21’s nose turret was faired over, while the dorsal turret was removed. The XB-21 proved to have superior performance over its competitor, but price became the primary factor distinguishing the B-18 Bolo and the XB-21. On this account, the modified B-18 was declared the winner of the competition by the US Army Air Corps, Douglas quoting a price per aircraft of $64,000 USD, while North American’s estimate was $122,000 USD per aircraft. The USAAAC placed an order for 177 of the Douglas aircraft, to be designated the B-18A. Despite this, the Army Air Corps found the performance of the XB-21 to have been favorable enough to order five pre-production aircraft, to be designated YB-21. However, soon after this contract was awarded, it was cancelled.

With a crew of 6 to 8, the XB-21 was powered by 2 × Pratt & Whitney R-2180 Twin Hornet turbosupercharged radial engines of 1,200 hp (890 kW) each, giving a maximum speed of 220 mph, a range of 1,960 miles with 2,200lb of bombs and a combat radius of 600 miles with a 10,000lb bombload. The service ceiling was 25,000 feet and dfensive armament consisted of five .30-calibre machine guns, mounted in single turrets in the nose and dorsal positions, and single manually operated mounts in the waist and ventral positions.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation team tested both the B-18 Bolo and the XB-21 and considered both to be “reasonable” medium bombers but expressed reservations about their performance.

The Piaggio P.32 (Italy)

The Piaggio P.32 was an Italian medium bomber of the late 1930s, produced by Piaggio, and designed by Giovanni Pegna. The P.32 was a twin-engine monoplane with a crew of five or six. The main structure was of wood, with a glazed nose, low cockpit, twin tail-fins, and a distinct ‘banana’ shape in the fuselage. Utilizing their experience of designing experimental and record-breaking aircraft like the Piaggio P.16, Piaggio P.23M, and Piaggio P.23R, Piaggio designed the P.32 with very small wings for its size. This meant a high wing loading, which required Handley-Page leading edge slats and double trailing-edge flaps to provide enough lift at takeoff and landing.

The development of this aircraft began with the contest announced by the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force) in 1934. The P.32 was one of many contenders, and certainly the most modern. The prototype first flew in 1936, and was tested at Guidonia, leading to an order for 12 aircraft, followed by a second order for five. These aircraft were fitted with the 615 kW (825 hp) Isotta-Fraschini Asso XI.RC inline V12 engine, and were designated the P.32 I. In early 1937 the P.32 Is were assigned to XXXVII Gruppo BT, 18 Stormo. The advanced wing design meant that they could only be flown by specially-trained crews. However, after entering service the aircraft was found to be fatally underpowered, with a maximum speed of only 386 km/h (240 mph), and then only with no bombs or defensive weapons carried. They were unable to fly on only one engine, and their handling qualities were markedly inferior to the SM.79 and BR.20.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation team test flew the aircraft but found it underpowered and with poor handling and maneuverability. With a full load of bombs and fuel taking off ranged from problematical to impossible. The P.32 was quickly eliminated from consideration, not least because the Ilmavoimat test crews regarded the aircraft as a crash waiting to happen.

he Piaggio P.32 had a crew of 5 or 6, a maximum speed of 240mph, a range of 1,212 miles and a service ceiling of 23,780 feet. It was armed with a dorsal turret with two 7.7 mm (.303 in) machine guns, a ventral turret and a single machine gun in the nose, and it could carry a 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) bombload.

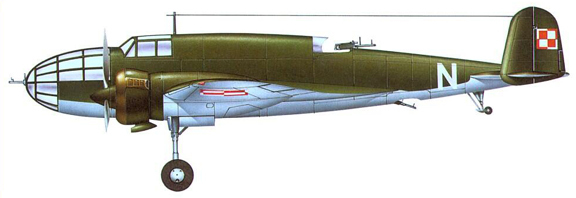

The PZL.37 Łoś (Poland)

The PZL.37 was a twin-engine medium bomber designed in the mid 1930’s and built by PZL (Panstwowe Zaklady Lotnicze – National Aviation Establishment). It was the most modern aircraft in the inventory of the Polish Air Force and a symbol of Polish technological ingenuity. Thanks to several advanced technological designs (including a laminar-flow wing), and combining good performance and manoeuvrability with high bomb carrying capability, it was one of the best bombers in the world at the outbreak of World War II. In size it was slightly larger than the Lockheed L-10 Electra.

The PZL P.37 was developed in response to the specifications issued by the Departament Aeronautyki (Department of Aeronautics) in 1934 for a new twin engine bomber capable of carrying a bombload of 2000 kg (including 300 kg bombs) with speed in excess of 350 km/h and a range of 1200 km. The task of designing a new aircraft was given to a team of engineers led by Jerzy Dabrowski and Piotr Kubicki. The design was an aerodynamically “clean” fuselage with a small elliptical cross-section that enabled the plane to reach a speed of 400 km/h. This however, necessitated the inclusion of bomb bays in the wings. To accommodate the bomb bays Dabrowski designed a new wing profile of very good aerodynamic characteristics that was similar to the first laminar profiles, which become widely used in military aircraft later during the war. The wing also featured a caisson patented by Dr. Misztal and successfully used in the Polish challenge aircraft PZL.19 and PZL.26. The Departament Aeronautyki accepted Dabrowski’s project with a few minor modifications such as a reduction of the aircraft’s defensive armament in favour of achieving higher speed.

Construction of prototypes commenced in 1935, with the first PZL.37/I prototype, fitted with a single vertical stabilizer and powered by Bristol Pegasus XIIB engines, flying on December 13 1936. This revealed several problems with the fuel system, main undercarriage shock absorbents, rudder etc. These were fixed by PZL and in 1937 the aircraft was transferred to ITL (Aviation Technology Institute) for further testing. The second prototype (P.37/II, 72.2) was completed in 1937. The second prototype PZL.37/II, with twin vertical stabilizers in place of a single one to improve the rear field of fire and other improvements such as a redesigned cockpit and a revolutionary new undercarriage (designed and patented by Piotr Kubicki) with sway beam and twin wheels replacing the heavy main undercarriage unit with a single wheel, and this was accepted for production. During testing of the prototypes P.37/I was lost due to inadequate riveting of the main wing that caused the wing to break off during flight. In the same year (1937) PZL received an order for 10 production PZL P.37A’s which was soon increased to 30 aircraft. The first 10 serial aircraft were produced in 1938 and were powered by the Bristol Pegasus XII B radial engines produced in Poland under licence. The main production variant, the PZL.37B, was fitted with the twin tail and newer Pegasus XX engines. Production of PZL.37B for the Polish Air Force by Panstwowe Zaklady Lotnicze (PZL) started in autumn 1938.

Two aircraft of the second order were converted to demonstrator aircraft and were used to test Gnome-Rhone (GR) 14N engines – this became a prototype for the export variant. The aircraft was demonstrated in Greece, Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia where it was shown in Belgrade during the International Aviation Show in 1938. During the same year this aircraft was also shown in Paris. The Łoś was very well received by international aviation experts and was considered to be one of the best bombers at the time due to its high speed and bombload. It was able to carry a heavier bombload than similar aircraft such as the Vickers Wellington, though the size of the bombs was limited. Smaller than most contemporary medium bombers, it was relatively fast and easy to handle. Thanks to the new landing gear with double wheels it could also easily operate from rough fields or meadows.

Typically for the late 1930s, its defensive armament as designed consisted of only 3 machine guns, which proved too weak against enemy fighters. For export purposes, new variants were developed: the PZL.37C with Gnome-Rhone 14N-0/1 engines of 985 cv (971 BHP, 724 kW), and a maximum speed 445 km/h and the PZL.37D with 14N-20/21 of 1,065 cv (1,050 BHP, 783 kW) and a maximum speed 460 km/h. The crew consisted of four: a pilot, commander-bombardier, radio operator and a rear gunner. The bombardier was accommodated in the glazed nose. The radio operator sat inside the fuselage, above the bomb bay, and also operated an underbelly rear machine gun. The main undercarriage retracted into the engine nacelles. The undercarriage was double-wheeled, with an independent suspension for each wheel – thanks to this landing gear it could easily operate from rough fields or meadows. It was also able to carry a heavier bombload than similar aircraft, for example the Vickers Wellington though the size of the bombs was limited. The bombs were carried in a two-section bomb bay in the fuselage and 8 bomb bays in the central section of the wings. The maximum load was 5,690lb of bombs (2 × 600lb and 18 × 250lb). Apart from two 600lb bombs, it could not carry bombs larger than 250lbs.

Starting with a presentation at an Air Show in Belgrade in June 1938 and in Paris in November, the PZL.37 met with a huge interest. For export purposes, new variants were developed: the PZL.37C with Gnome-Rhô:ne 14N-0/1 engines of 985 cv (971 BHP, 724 kW), maximum speed 445 km/h and the PZL.37D with 14N-20/21 of 1,065 cv (1,050 BHP, 783 kW), maximum speed 460 km/h. In 1939, 20 PZL.37Cs were ordered by Yugoslavia, 12 by Bulgaria, 30 PZL.37Ds and a production license by Romania and 10, raw materials and parts for another 25 and a production license by Turkey and, finally, 12 aircraft for Greece. The Belgian company Renard received permission for the license production of 20-50 aircraft for Republican Spain but cancelled this in 1939. Also Denmark, Estonia and Iran were negotiating. Deliveries to the Polish Air Force were very slow due to delays in deliveries of radio equipment, guns, bomb racks and propellers. However, by 31 August 1939 the Polish Air Force had a total of 86 PZL P.37s in service: An additional 31 airframes were at different stages of assembly in Okecie and Mielec.

With a crew of 4, powered by Bristol Pegasus XX radial engines of 723 kW (970 hp) each, the PZL.37B had a maximum speed of 256mph, a combat radius of 630 miles, a service ceiling of 23,000 feet and could carry up to 5,690lb of bombs. Defensive armament consisted of 3 machineguns, one in the nose, 1 in the rear upper station and 1 in the underbelly station.

However, a number of modifications were recommended in the event a decision was made to purchase the aircraft. The most significant of these was a recommendation to replace the glazed nose with a solid nose fitted with four Hispano-Suiza 20mm cannon has had been done with the Ilmavoimats Bristol Blenheims and armour protection for the Pilot. As a result, the Commander-Bombardier position would be eliminated and the Pilot would function as Pilot, Bomb-aimer and Radio-operator combined. It was also recommended that the Radio Operator / Ventral Gunner position be eliminated and the ventral gun removed completely while the rear upper station be upgraded to two machineguns. The fitting of more powerful engines was also recommended – the Rolls Royce Merlin II (rated at 1,030-horsepower 770 kW) and with production starting in Finland. It was however expected that this engine would soon see a major increase in performance. With the Finnish Oil Refinery online, Neste had been experimenting with the production of 100 octane fuel for the Ilmavoimat and the adapatation of the Merlin engine to run on this was being trialled, with initial results indicating the result would be an increase in power to some 1,265 horsepower. With these or similarly upgraded Hispano-Suiza 12Y engines fitted, an increase in speed to some 280mph was projected.

(For comparison, the slightly later B-25 Mitchell had a maxium speed of 275mph, a combat radius of 1,350 miles and a bombload of 6,000lbs). It was also significantly larger and was powered by 2 × Wright R-2600 “Cyclone 14” radials of 1,850 hp (1,380 kW) each).

The Ilmavoimat evaluation team rated the PZL 37 highly. It was small and highly maneuverable, had excellent rough-field capability and could carry a significant bombload. Combat radius was somewhat limited however and defensive armament was on the light side. Maximum speed was considered acceptable.

OTL Note: German air superiority, dispersal of Polish bomber units and inadequately equipped field airstrips prevented the effective use of Poland’s aircraft in the September 1939 Campaign. The Łoś was mainly used for missions that included reconnaissance and bombardment of German mobile forces, a task for which the Łoś was not intended. Moreover, none of the sorties included a large enough number of aircraft to inflict any real damage. Repairs of damaged aircraft were not possible since the ground crews did not have all the essential equipment and battle worthiness was further affected by the fact that most of the aircraft were not fully equipped (radio, compass, etc.). A shortage of fuel and an inability to coordinate operations with Polish fighters (it should be noted that PZL P.37 was much faster than any of the contemporary Polish fighters) made the situation even worse. Most of the bombing missions involved attacks on randomly chosen mobile German forces and a total of 119 tonnes of bombs were dropped.

27 aircraft were lost during the hostilities: 11 were destroyed by enemy fighters, 5 by enemy AA fire, 1 by friendly AA fire, 2 were destroyed on the ground by enemy bombers, 3 were abandoned by crews due to technical difficulties, 3 were damaged on the ground and lost due to the pilot error, 2 crash landed due to lack of fuel. German forces captured a total of 41 PZL 37s in Warsaw and Mielec. Those aircraft were at different stages of assembly although several were completed. Polish workers used by the Germans to clear airfields destroyed the majority of them, which resulted in only two PZL P.37B’s being airworthy. German war booty also included 50 brand new PZL Pegasus XX engines that were sold to Sweden. Polish crews evacuated 27 P.37s to Romania. These aircraft were seized by the Romanian government and despite Polish government’s diplomatic efforts backed up by France and Great Britain the aircraft were never returned to Polish Air Force, which new squadrons were being formed in France. Later on the aircraft equipped 76 and 77 Squadron of Fortele Aeriene Regale Romane (Royal Romanian Air Force) and took part in the attack on Soviet Union in 1941.

Polish Air Force PZL 37s in Finland

On September 1, 1939, Poland had about 86 PZL.37s in service. With Poland on the verge of defeat and under attack from both Germany and the Soviet Union, twenty-seven PZL.37s (17 from the Bomber Brigade and ten training aircraft) loaded as many of their squadron personnel as was possible into the aircraft and flew to Finland.

The Ilmavoimat incorporated these aircraft and personnel immediately and they went on to fly as a Polish Volunteer Squadron in the Winter War. Polish flying skills were well-developed and the Polish pilots and aircrew flying for Finland in the Winter War were regarded as fearless bordering on reckless. Success rates were very high, on a par with the Ilmavoimat pilots in point of fact. German war booty from Poland also included 50 brand new PZL Pegasus XX engines that were sold to Sweden – these were promptly resold by Sweden to Finland for use by the Ilmavoimat as spares.

The Polish aircraft retained the Polish insignia and fought as a “Polish Air Force unit attached to the Ilmavoimat” during the Winter War, considering themselves at war with the USSR. A considerable number of Polish Air Force personnel managed to find their way to Finland over the course of the Winter War, as eager to continue the fight against the USSR as they were to also fight Germany.

The Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 (Italy)

The SM.79 project began in Italy in 1934, where the aircraft was first conceived as a fast, eight-passenger transport capable of being used in air-racing (the London-Melbourne competition). Piloted by Adriano Bacula, the prototype flew for the first time on 28 September 1934. Originally planned with the 800 hp Isotta-Fraschini Asso XI Ri as a powerplant, the aircraft reverted to the less powerful 590 hp Piaggio P.IX RC.40 Stella (a license-produced Bristol Jupiter and the basis of many Piaggio engines). The engines were subsequently replaced by Alfa Romeo 125 RC.35s (license-produced Bristol Pegasus). This prototype was completed too late to enter the London-Melbourne race, but flew from Milan to Rome in just one hour and ten minutes, at a 410 km/h average speed. Soon after, on 2 August 1935, the prototype set a record by flying from Rome to Massawa in Eritrea in 12 flying hours (with a refuelling stop at Cairo).

The SM.79 had three engines, with a retractable tailwheel undercarriage and featured a mixed-material construction, with a box-section rear fuselage and semi-elliptical tail. Like many Italian aircraft of the time, the fuselage of the SM.79 was made of a welded tubular steel frame and covered with duralumin forward, duralumin and plywood over the top, and fabric on all other surfaces. As with most cantilevered low-wing monoplanes, the wings were of all-wood construction, with the trailing edge flaps and leading edge slats (Handley-Page type) to offset its relatively small size. The internal structure was made of three spars, linked with cantilevers and a skin of plywood. The wing had a dihedral of 2° 15′. Ailerons were capable of rotating through +13/-26°, and were used together with the flaps in low-speed flight and in takeoff. The grouping of engines, the slim fuselage, coupled with a low and wide cockpit and the “hump” gave this aircraft an aggressive and powerful appearance. Its capabilities were significant with over 2,300 hp available and a high wing loading that gave it characteristics not dissimilar to a large fighter.

The engines fitted to the main bomber version were three 582 kW (780 hp) Alfa Romeo 126 RC.34 radials, equipped with variable pitch, all-metal three-blade propellers. Speeds attained were around 260mph at 12,000 feet, with a relatively low practical ceiling of 23,400 feet m. The best cruise speed was at 60% of power. The landing was characterized by a 125 mph final approach with the slats extended, slowing to 90mph with extension of flaps, and finally the run over the field with only 600 feet needed to land. With full power available and flaps set for takeoff, the SM.79 could be airborne within 900 feet then climb to 12,000 feet in 13 minutes 2 seconds. The bomber version had ten fuel tanks (3,460 l).The endurance at full load averaging 200mph was 4 hr 30 min. In every case, the range (not endurance) with a 1,000 kg payload was around 5-600 miles.