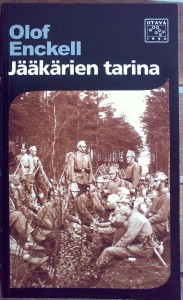

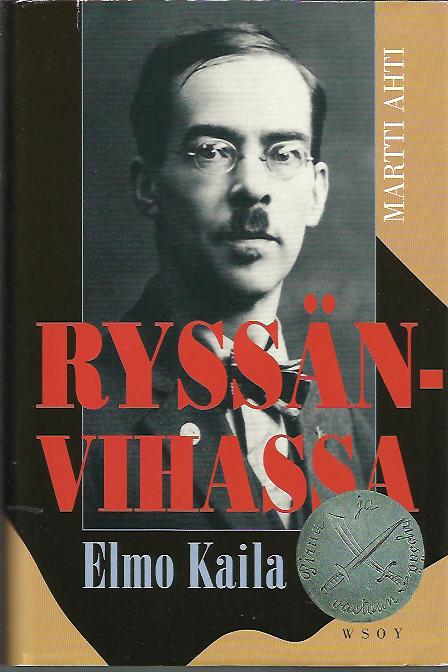

This section is split into two parts – the first is the purely historical story of the Jääkärit (the Finnish Jaegers) in World War One and the Finnish Civil War. The second is a study of the “myth”of the Finnish Jaegers and the part the Jaegers played in the formation and leadership of the Finnish Army in the decades of the 1920’s and 1930’s.

The story of the Jääkärit – the Finnish Jaegers

The Jääkärit (Finnish Jaegers) German = Jägers or Jaegers, were nationalist volunteers from Finland who fought for a Finland free from, and independent of, Russia. Trained in Germany as Jägers (elite light infantry) during World War I, they were supported by Germany in their mission to establish a Finnish sovereign state free of Russian oppression. For the Germans, it was one of many means by which Germany intended to weaken Tsarist Russia and cause Russia’s loss of her western provinces and dependencies.

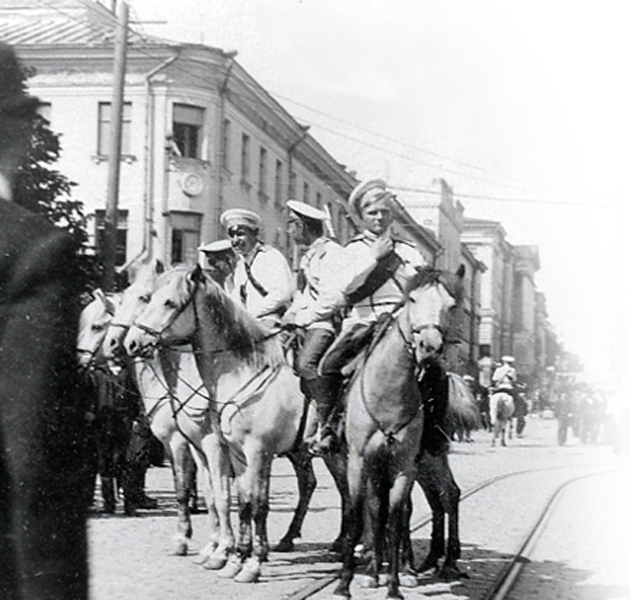

Russian gendarmerie in Helsinki in the early 1900’s

The emergence of the Jääkärit took place in the milieu of an awakening Finnish nationalism in the late 1800’s and the Russian repression at the turn of the 1900’s, where Russia sought the Russification of the Grand Duchy of Finland and the destruction of the Grand Duchy’s internal autonomy. This repression over the years 1899-1905 and a second period that began in 1908 created a strongly anti-Russian sentiment within Finland. When WW1 broke out in 1914, many Finns wanted to see Russia defeated. The early defeats suffered by the Russians encouraged these hopes and in Helsinki, student activists became more active.

In November 1914 the Russian government announced measures which would have meant the end of Finnish autonomy. Anxiety grew in Finland and on November 20th, the Finnish independence movement began organising. The activists objective was to drive Russia out of Finland and it was considered that this goal could only be achieved by force. Thus, it was decided to take steps to create an Army of Finland.

Student Activist Bertil Paulig was one of those to show initiative

The Independence Movement consisted largely of young people, many of them University graduates. These activists saw the need for a Finnish Army to acquire weapons and trained leaders. Clandestine links with Germany were established and in January 1915 the German High Command and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs approved the military training of 200 Finns. Student activist groups immediately began secretly recruiting Jäger volunteers from the Grand Duchy of Finland. The recruiting was clandestine, and was dominated by German-influenced circles, such as university students and the upper middle class. The recruitment was however in no way exclusive. The recruits were transported across Finland’s western border via Sweden to Germany, where the volunteers were formed into the Royal Prussian 27th Jäger Battalion (Königlich Preussisches Jägerbataillon Nr. 27).

The Finnish Jaegers objective was to secure Finland’s independence and fighting with the Germans against Russia was seen as their best chance to achieve this goal. It was an almost religious call, and the Jaegers themselves even at this time felt that they were establishing a spiritual heritage for all Finns: “our legacy to you, the youth and future generations of Finland, is to leave you what we think most valuable – confidence in Finland’s future as an independent and free country, unwavering faith in the legitimacy of the fight for freedom and for victory, even when all seems hopeless, the will and courage to fight at all times on behalf of this cause.”

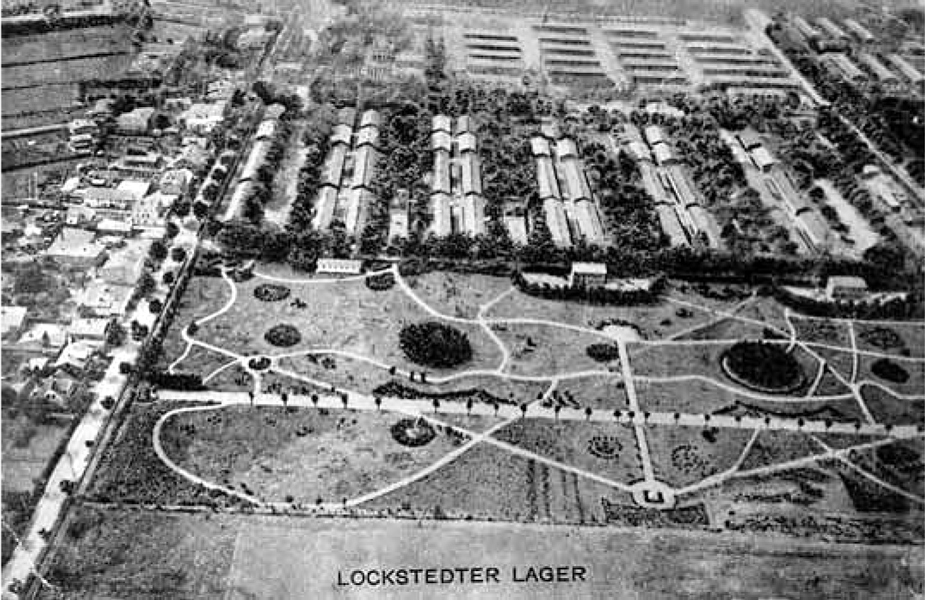

At first, all went without difficulty using the route through Sweden to Germany. Training took place in the camp Lockstedt Camp. The first men arrived there 25 February 1915 with a total number of 189 volunteers. The majority of the volunteers, 145 men, had passed the matriculation examination. Among them, 34 also possessed an academic degree. For the majority, about 64%, their mother tongue was Swedish. The Finnish volunteers were initially not treated as soldiers, but as guests of the German Reich and as civilians. They initially dressed as German Boy Scouts for disguise and they were called Pfadfinder. Later volunteers received a German infantry uniforms and were nicknamed the Three Musketeers.

Their legal status remained unchanged and so they underwent training for first four weeks, but the training was extended time and again. The training was appropriate and effective – and was mainly responsible for the subsequent Finnish reserve officer training in independent Finland. The course leader and commander of the Finnish volunteers since the beginning of January 1917 was German Army Major Maximilian Bayer. The trainers were four German officers and a number of non-commissioned officers. A number of Finnish volunteers were promoted to Officer’s positions.

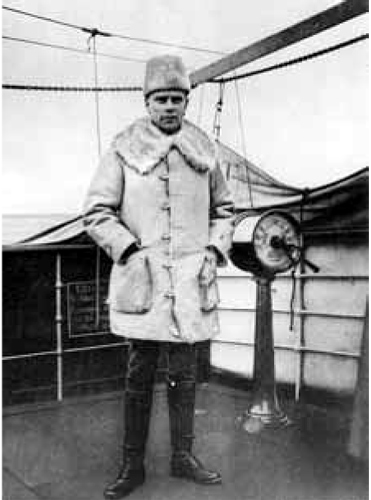

The course leader and commander of the Finnish volunteersfrom January 1917 – Major Maximilian Bayer

Major Maximilian Bayer was born on 05 November 1872 in Karlsruhe. He had received his first war experience as a staff officer in Africa. He was a German Boy Scout Association founder and was chairman until his death. Major Bayer was well educated. He was a writer, well-known speaker, connoisseur of music and a youth educator. He supported with all his heart the Finnish freedom fighters in training and in their military education. Major Bayer fell as a regimental commander on the French front near Verdun 25 October 1917. He was buried in Mannheim. A Finnish memorial stone stands by his tomb.

In August 1915 the Emperor Wilhelm II signed a decree authorizing the expansion of the Pfadfinder Course with a target strength of 2,000 men. More than 200 university students had participated in the so-called “Boy Scout” training – they dressed in Boy Scout uniforms during the training, and theses went on to become the Officers of the Finnish Jääkärit (Jäger) Troops. This group was expanded by extensive recruitment over autumn 1915 and spring 1916.

Back in Finland, an Action Committee for Recruiting was formed, with the support of the Central Committee, which was made up largely of older Activists. All the non-Socialist Political Parties of Finland were represented in the Central Committee. Although the Social Democratic Party was excluded from the Committee, many SDP party leaders supported the independence movement and the SDP itself did not set policy for members on this issue. The Recruiting Committees tendency to form a nation-wide, centrally managed recruitment organization did not lead to the desired result. Local recruiters were forced to act independently as the country was in a state of war and strictly supervised by the Russians in the country.

The Lockstedt Training Corps

Document date: Aug. 26, 1915.

M.J.13630/15 A.I. Confidential.

1. An immobilized formation will be raised in Lockstedt Camp, which will be known as “The Lockstedt Training Corps”. It will consist of several companies, which will be gradually brought up to the strength of a battalion of D. II. 3 type, with a machine-gun company and a pioneer company.

2. Enrolment in this company is open to foreigners who enlist voluntarily. Foreigners accepted for service in it will not acquire German nationality. The army administration will undertake no liability to endorse applications for naturalization. The army administration will also undertake no responsibility for the financial support of any such foreigners disabled by wounds received on active service with the German Army. Furthermore, the relatives of such persons will have no claim on the German Government for compensation in the event of the death or total disability of the persons concerned. This must be confirmed in writing by every individual serving in this formation. Foreigners must be warned before enlistment that it will be their duty to support the German Reich to the best of their ability, to serve wherever they may be sent, to obey all orders given them by their superiors and to obey the German civil and military laws and whatever regulations may have been issued for the duration of the war.

3. In all service, administrative and legal matters the formation will be under the direct orders of the general commanding the 9th Army Corps. The High Command will decide the nature of its future employment. The formation will be commanded by Major Bayer, of the 27th Infantry Regiment, who will receive the authority of an independent battalion commander. He will apply to the general commanding the 9th Army Corps for the appointment of any further subordinate officers or instructors he may require. The War Office will supply the necessary material resources. Major Bayer will be responsible for the supply of new recruits, and for this purpose the War Office will place at his disposition three officers and three N.C.O.s in addition to those on the regular strength of the formation.

4. The War Office will supply rifles, ammunition and machine-guns (exclusively captured Russian material) and all other training material which the commander may deem necessary. Furthermore, twelve bicycles will be supplied for the use of every company, including the pioneer company. The material for four field telephone sections will also be supplied by the War Office. The 9th Army Corps will supply any horses deemed necessary.

5. The formation will be trained on German principles. Words of command will be given in German. Clothing and equipment of a German Jaeger Regiment (shoulder straps without regimental number) will be supplied by the 9th Army Corps. Pay and rations on the scale in force for immobilized troops. Foreigners may be promoted to N.C.O. ranks to bring them up to strength. They will then receive the pay carried by the rank in question, but will not wear the distinguishing marks of such ranks. They will not be deemed superiors of German N.C.O.s of lower rank or German privates. For this purpose they will be given the ranks of section-leader, group-leader and assistant-group-leader instead of the German ranks of staff sergeant, corporal and lance-corporal, and shall be superior officers over all foreigners in the formation who hold no rank.

6. The Lockstedt Camp unit formed by the order of February 23rd, 1915, is merged into the new formation.

7. The commanding officer will make monthly reports to the 9th Army Corps and the War Office on the strength of the formation, the progress of its training and any other matters which may arise. The first report is due on October 1st.

8. The existence of this formation is to be kept as secret as possible. The contents of this document will therefore be imparted only to those authorities immediately concerned with the work of the formation and only in an epitomized form. No mention of the formation must appear in the Press.

Signed: Wild von Hohenborn.*

From the book: “Finland Breaks the Russian Chains” by Heinz Halter. Translated from the German by Claud W. Sykes. John Hamilton Ltd., London, 1940. Major Bayer’s picture is from the book “Jääkärit maailmansodassa” (The Jägers in the World War), ed. E. Jernström, Helsinki 1933.

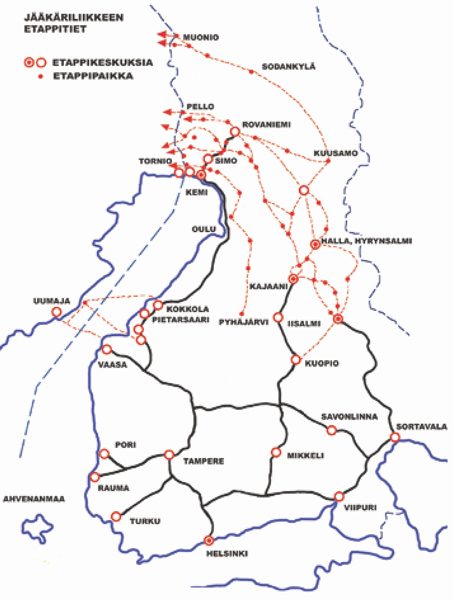

The routes for recruits from Finland into Sweden were varied

Nevertheless, recruiters were abundant. Most of them were civilian men. Their positions in society were mixed, but generally they were well-known in their home regions, and were prominent personalities. Students served as the conduit between recruiting offices in the capital and the provinces. The new recruits included young working class men and farmers as well as sailors and students, and the numbers of recruits sent to Lockstedt was significant. Reaching Germany required some hard traveling. Routes across the border were staffed by local residents or Jaegers. Crossing the border was dangerous and often required a long trek on foot or on skis. Starting positions were reached by rail from southern Finland, with the most important escape route leading from Kemi to Haparanda across the Torne River and thence south through Sweden. Another route was from the coast of Ostrobothnia across the Gulf of Bothnia to Umeå. During the open water season, the Gulf was crossed by boat.

In the late winter and spring of 1916 the Russian gendarmes arrested about fifty activists with some armed clashes. Recruitment was revived by sending volunteers through remote areas with local guides, one of whom, the farmer Juho Heikkinen, or “Old Man Frost” was the bravest of the Jääkärit’s helpers. By May 1916 a considerable number of men had made it to Germany and were undergoing infantry training. Finnish troops were a kind of miniature people’s army, representing all occupational groups and ages between 15-49. The average age in 1916 was less than 24 years and the difficult and dangerous conditions of recruitment had not deterred the volunteers, the majority of whom were good military material. Suitable men for Officers were in also abundance.

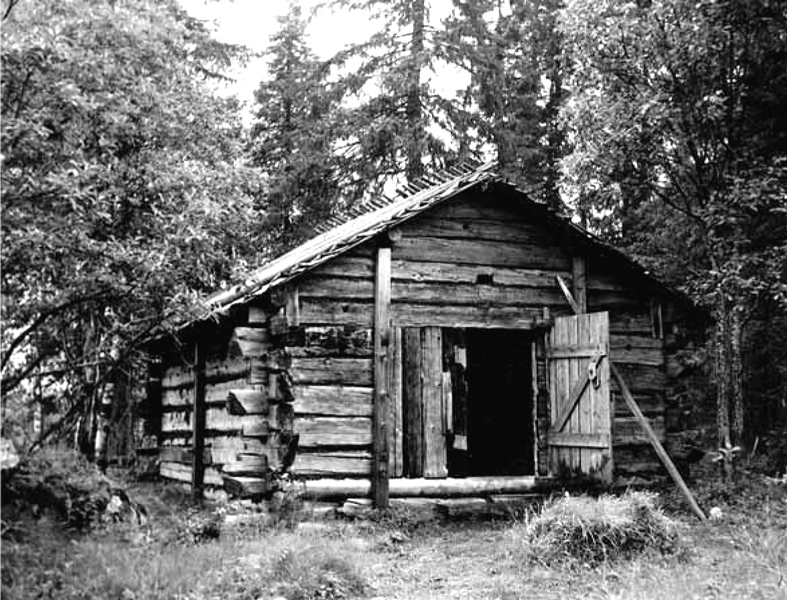

Site of the December 1916 skirmish

Site of the December 1916 skirmish: Simon Meadow – Eight men hidden in the Sauna were discovered by a Russian NCO and his men. In an exchange of gunfire at dawn one man fell on the step, two were captured.

Around August-September 1915 the voluntary legal status of the Finnish volunteers was changed. They became soldiers of the German Army but were not required, however, to take the military oath. Instead, they had to make a commitment to serve Germany with all their might (under the laws of Russia and Finland, the volunteers committed treason). From September 1915 to May 1916 the Finnish volunteers trained at Lockstedt. The courses were structured to train as many of the Finns as possible in the leadership and in the needed military skills for their assigned Finnish military branches of service. The initial establishment was two Rifle Companies (kiväärikomppaniaa), a machine gun company and a Pioneer Company. Two further kiväärikomppaniaa were added, together with a field artillery unit (kenttätykkijaos?).

From the autumn of 1915, arriving Finnish recruits knew almost no German, and it was concluded that most would never learn the level of German necessary for the German military. It was therefore necessary to create military manuals in Finnish, and to come up with a Finnish military vocabulary. Due to language requirements for training of the men, German officers and non-commissioned officers needed to be supplemented by Finnish Officers and NCO’s.

Finnish Officers and NCO’s were therefore used as trainers. The German military ranks differed from their own Finnish ranks. The Senior Finnish Platoon Commander (pääjoukkueenjohtaja) was appointed the battalion commander and the company commanders were the next ranking Finnish soldiers (ylijoukkueenjohtaja). Erik Jernström was appointed the Finnish commander (Pääjoukkueenjohtajaksi) and held this role until the dissolution of the battalion. In all, during the existence of the battalion 19 Company Commanders (ylijoukkueenjohtajiksi), 46 Platoon Commanders, 196 Senior NCO’s and 274 junior NCO’s were selected.

The training was run by the German officers and non-commissioned officers. The early soldier training focus was on fitness and close order drill training. Later, training focused on firearms and combat training. The German language was for many a very tedious subject. In this training, the Finns were acclimatized to Prussian discipline and precise adherence to tactics and orders. The training was tough, versatile and efficient and also reflected the latest war experiences. Some of the Finnish officers were also involved in running the training.

Lockstedter Lager in Schleswig-Holstein was used as a training area for the Finnish Volunteers

The Finns had an exceptionally good military education compared to the Germans, who were often sent to the front after only a short training period. The German trainers were very satisfied with the results of the training. In particular, Finnish marksmanship, marching ability and sports performance provoked awe. For the Jääkäri, the dark side of life were poor accommodation conditions, the (to the Finnish) strange and often inadequate food and a constant lack of money. The worst part, however, was homesickness, as well as the uncertainty of both their own and Finland’s fate. Shortcomings and concerns were somewhat alleviated by the local Holstein population’s welcoming attitude to the Finns.

Finnish Volunteers training with a machinegun at Lockstedt

Lockstedter Lager, the commandant’s house

As training progressed, the Jaegers were given more free time. In most cases, this free time was spent in the Lockstedt camp site or in the immediate surrounding area. The most popular evening venue was the Café Schütt, if the money was available. Some Finnish infantry officers and a number of NCO’s also visited different parts of Germany.

Cafe Schütt. was popular with the Finnish Jaegers

June 1916 and movement to the Eastern Front and the Misse River

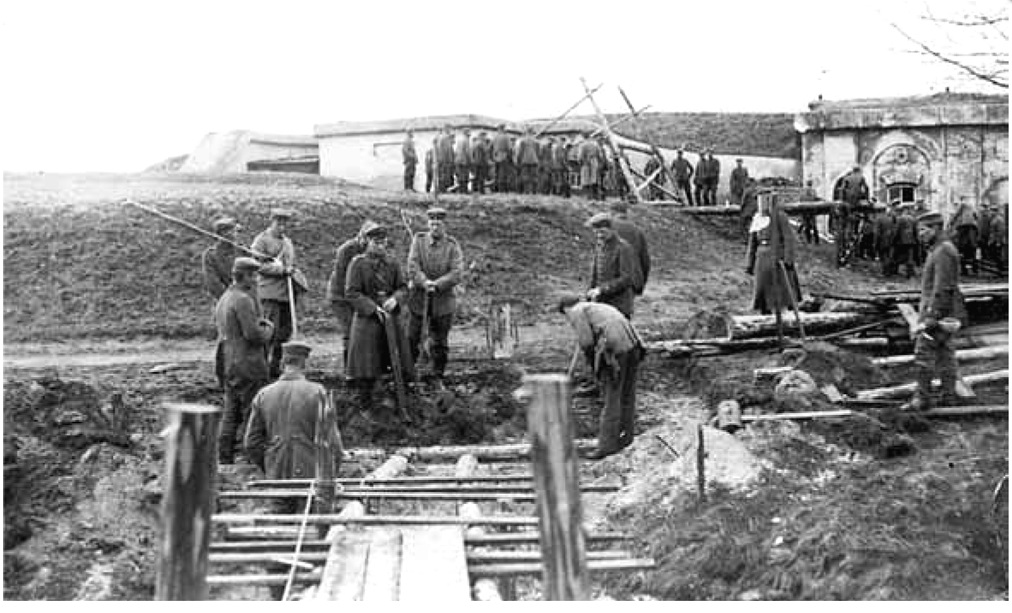

Major Bayer was in Germany at the end of 1915 meeting with a Finnish delegation and the German War Ministry negotiating for the Finnish volunteers to acquire frontline combat experience. It was at this time that the Finnish volunteers received the name Königlich 09/05/1916 Preussisches Jägerbataillon No. 27, (the Royal Prussian Jaeger Battalion 27). The battalion moved from Lockstedt to the German Eastern front in three trains at the end of May. At this time it had a strength of 203 Germans and 1254 Finns. On 11th and 12th of June 1916 the Battalion marched up to the front lines on the Gulf of Riga and was allocated a four kilometer front on the Misse River, in a swampy area. The Jaegers front service on the Misse River (Misa) was primarily to man picket duty stations and fortifications. Patrolling in no-mans land at times led to skirmishes with the Russians. The enemy’s artillery often fired on the Finnish positions.

In July 1916, two units of the battalion was forced to battle the battalion area of responsibility outside of the main components. Tykistöjaos (the Finnish artillery unit) participated in an attack against the Russian Ekkau-Kekkaun (Jecava-Kekava) front sector and an Engineer Company of the Jaeger Battalion participated in a German attack on the Schmardenin (Smārde) sector. Both the gunners and the pioneers won plenty of recognition from their German commanders for their performance on the battlefield. Slightly later the battalion was transferred to the Gulf of Riga Dumben (Klapkalnciems) sector. Here, the terrain was dry and the scenery was beautiful, but the enemy was active, which resulted in losses. The German military cemetery at Dumben (Klapkalnciemsin) is the place of burial of five Finnish infantryman who were combat casualties.

Christmas 1916 and the Aa River (Lielupe) battle

Jääkäripataljoonan officers foraging in winter during the fighting. In the middle Zugführer Lennart Oesch.

In late September 1916, dissatisfaction grew within the Battalion due to heavy combat service and uncertainty of their own future. Also, superior-subordinate problems occurred. Although the problems were moderate, a number of Jaegers were punished and some were sent to a labor camp. In December 1916 the Battalion handed over Front responsibility to German units and spent Christmas at Libaussa (Libau). They were there for just three weeks before being sent back to the front to fight the Russians on the River Aa (Lielupe), where an attack had been launched. In the end, winter and hard frost paralyzed all combat operations.

In January 1917 Major Bayer handed over battalion command to Captain Julius Knathsille. On 25 March 1917 the battalion was removed from the front. By this time the Finnish volunteers had received a relatively large amount of war experience, but had also suffered losses.

Finnish dead numbered 11, with one mortally wounded and one missing. A total of 49 infantrymen had been wounded. Worse than the combat casualties were variety of different diseases, with unhealthy conditions playing a role. Disease, mostly cases of tuberculosis, killed 15 men. The Jaeger dead were all buried in territory that is now part of Latvia, and almost all their graves have now been discovered and restored.

The Jaeger Battalion at Libaussa (Libau) 25 March 1917 – 13 February 1918

The peace-time garrison, spa and tourist town of Libau (Liepaja), located as it was by the sea and on the beach was a base that provided good educational opportunities. There were large-scale training fields, shooting ranges, fortifications and a military port. The old Russian barracks were, however, unsatisfactory. Termites were everywhere, the clothing situation was poor and the food insufficient. Cases of tuberculosis were in abundance. In mid-summer a malaria epidemic raged. Care of patients and spiritual support was provided by Finnish volunteer nurses Ruth Munck and Sarah Rampan, who did valuable work.

Ruth Margaret Munck ( August 12 1886 Lempäälä – September 30, 1976 ) was a Finnish baroness and a nurse. She studied at a Swedish co-educational school and then at a craft school Helsinki. In 1908 she started training as a Nurse in Helsinki, completing her training in 1910. At the end of the 1915 Ruth Munck went to Germany via Sweden. She already had apparently good connections with the volunteers, as in Stockholm, she was greeted by the Stockholm mission, including by Almar Fabritius. Through Fabritius, she met a number of high-ranking Jaegers and activists representatives.

She arrived in Berlin on 6 January 1916, where she worked in the Berlin University surgical clinic. Her first direct involvement with Jaeger Battalion 27 was at field hospital 55 at Jelgava (Mitau), where she started nursing in October 1916. In June 1917 she moved to field hospital 404 at Tukkum, and in August the same year, she moved to 124 military hospital in Liepaja (Libau). She was known among the soldiers of the battalion in the German way as Schwester Ruth (“Sister Ruth”).

Nurses: Baroness Ruth Munck and Miss Sarah Rampan did valuable work caring for the wounded or sick Jaegers. They worked in the territory of Latvia of war and a field hospital that had cared for Finnish light infantry. Both returned to Finland with the main body of Jaegers and served during the Civil War.

When the Finnish Civil War broke out, Ruth Munck arrived with the main body of the Jaegers at Vaasa on 25 February 1918 . During the Battle of Tampere she cared for the sick and wounded on a train, led by the German doctor Knape. After the capture of Tampere, Ruth Munck moved to the Karelian Isthmus with 2 IV Battalion Light Infantry Regiment. She worked in the field hospital led by Dr. von Hertzen. After the war, Ruth Munck returned to Helsinki. and in 1918, she married former Jaeger Battalion 27 company commander Eduard Ausfeldin, who had also participated in the 1918 civil war in Finland. They divorced in 1921. Ruth Munck took part in the formation of the Lotta Svärd Association from the beginning. In the period 1924-1932 she was the Lotta Svärd Association district chairman of local branch I and until 1928 she was on the association’s national board as medical chief. She was President of the Lotta Svärd Association from 1931 to 1933

At Libau, the Battalion established a second machine gun company, a cavalry unit and Communications Department. Captain Julius Knahts handed over the tasks of the battalion commander to Captain Eduard Ausfeldtille on 29/September/1917. Ausfeldtille became the last commander of the battalion. Officers and sergeant major responsibilities were transferred to the Finns. Pending return to their own country, the Finnish Jaegers were given further training by the Germans. Each man was given NCO training as well as a special course on destruction, sabotage and guerrilla training. Light infantry were also trained to use motor vehicles, maintain car and boat engines,manage the railway service, and a variety of maintenance tasks. One of the officers also received pilot training.

Radio Man – Men on the Course are practicing telegraphy under German non-commissioned officer leadership

During the period at Libau, the Jaegers drew up a Finnish military vocabulary. The most notable achievement over this period was the writing up of the more than 1,500-page Finnish military manual. The Finnish military professional literature was based on the work of a task force led by Oberzugführer Armas Ståhlberginkuja. Also at this time, Hilfsgruppenführer Heikki Nurmio wrote the lyrics for the Jaeger march, the music for which was later composed by Jean Sibelius. The march was of great importance to the Jaegers cohesion and morale.

Syvä iskumme on, viha voittamaton (Deep is our blow, invincible our wrath,)

meil’ armoa ei, kotimaata. (we have no mercy, no homeland.)

Koko onnemme kalpamme kärjessä on, (All our luck is in the tip of our swords,)

ei rintamme heltyä saata. (our hearts will not give in.)

Sotahuutomme hurmaten maalle soi, (Our war cry rings out, thrilling the country,)

mi katkovi kahleitansa. (which is breaking her shackles.)

ei ennen uhmamme uupua voi, (Our defiance will not tire,)

kuin vapaa on Suomen kansa. (before the Finnish nation free.)

Kun painuvi päät muun kansan, maan, (When the heads of the people, the country, bowed down)

me jääkärit uskoimme yhä. (we Jäegers still believed.)

Oli rinnassa yö, tuhat tuskaa, (There was darkness in our chests, a thousands pains,)

vaan yks’ aatos ylpeä, pyhä: (but one single thought proud, sacred:)

Me nousemme kostona Kullervon, (We shall arise as the vengeance of Kullervo*,)

soma on sodan kohtalot koittaa. (sweet it is to face the fates of war.)

Satu uusi nyt Suomesta syntyvä on, (A new tale of Finland will be born,)

se kasvaa, se ryntää, se voittaa (it will grow, it will charge, it will win.)

Häme, Karjala, Vienan rannat ja maa, (Häme, Karelia, the coasts and lands of Viena,

yks’ suuri on Suomen valta. (there will be a single great country of Finland.)

Sen aatetta ei väkivoimat saa (The idea of her cannot be removed by violence,)

pois Pohjolan taivaan alta. (away from beneath the northern sky.)

Sen leijonalippua jääkärien (Her Lion Flag is carried)

käsivarret jäntevät kantaa, (by the strong hands of the Jäegers,)

yli pauhun kenttien hurmeisten (Over thunderous, gory fields)

päin nousevan Suomen rantaa. (towards the shores of rising Finland.)

The Jäger March was written by the Finnish Jäger Heikki Nurmio (1887-1947) in Libau, Prussia, in 1917 where a competition was held for the best lyrics for a march song. The lyrics were smuggled into Finland, where Sibelius received them from his ear doctor, Dr Wilhelm Zilliacus. Sibelius was enthusiastic about the song and composed the march in three days in his villa Ainola in Järvenpää. According to his own account he was overwhelmed by highly patriotic emotions as he wrote.

The march was presented for the first time in Libau on 28 November 1917 in a leisure occasion for the staff of the Battalion. It was published in December 1917 as written for a male choir and piano, without mentioning the writer of the lyrics or the composer. In Finland, the march was apparently presented for the first time to a larger audience in a celebration of the New Day Club made up of advocates of independence in the restaurant Ylä-Oopris in Helsinki on 8 December 1917. The proper debut of the Jäger March was in Helsinki on 19 January 1918, by the choir of Akademiska Sångföreningen, led by Olof Wallin. On the same day, the first battles broke out in Karelia between the Reds and the Whites, related to the weapons supplies to the Reds from St Petersburg.

Kullervo is a tragic hero of Kalevala, the national epos of the Finns, and this detail, a single word of the lyrics, is packed with strong sentiment to anyone familiar with Kalevala.

*In the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic, Kullervo, the son of Kalervo, is an orphan, whose whole family has been murdered by sword by the men of Untamo, Kalervo’s foe. Only a maid was left alive and taken as a slave, but she gave birth to this son of Kalervo. The boy is put to work but he proves of no use, they try to kill him but fail. Finally Kullervo is sold to Ilmarinen. He sends Kullervo to herd cattle, but his wicked wife, the daughter of Pohjola (North), bakes a stone inside the bread that is packed as a meal for Kullervo. When cutting the bread, Kullervo breaks his puukko knife, his only heritage of his father, on the stone. Infuriated by this he swears revenge. In his relentless, fierce hate of the unjustly oppressed, he puts a magical spell on the bears and wolves of the forest, driving them to kill all the cattle and the wicked wife as well.

Jaegers outside the Battalion

Jaeger Battalion 27’s departure to the front from Lockstedt in May 1916 saw most of the Finnish volunteers move to the front. However, in addition to Jaeger Battalion 27 there was another group of Finnish Jaegers within the German Army over 1916-1917. This was the Altona Bahrenfeld artillery depot punishment unit (työkomennuskunta). From December 1916, Jaegers who were responsible for serious violations against military discipline were sent to this unit. A total of 224 Jaegers were sent to Bahrenfeld as punishment, were they were sentenced to hard labour. Most were released in August 1917. Jaegers who were judged unsuitable for military service were placed in employment in German civilian jobs, mainly in the service industry. In all, some 512 Jaegers were sent or released into civilian work; of these, 32 returned to the Battalion.

There were also casualties related to a devastating train accident at Osnabrück, where a train collision on 16.01.1918 resulted in the death of Transport Officer, Gruppenführer Alfons Arlander and 11 other Jaeger casualties. Jaegers were also trained in reconnaissance and sabotage.Their most significant achievement was the destruction of a large store of Russian munitions at Kilpisjärvi in the summer of 1916. A total of 19 Jaegers who had been recruited for intelligence or sabotage work from the Pfadfinder Jaegers were captured by the Russians in Finland. Of these, 13 ended up in St. Petersburg in the Spalernajan Prison, which also held 60 Finnish male civilian independence activists. The trial of these “kalterijääkäreitä” (Prison Jaegers) was in progress when in the middle of February 1917 the Revolution broke out and the prisoners were released.

The Jaeger homecoming in 1917-1918

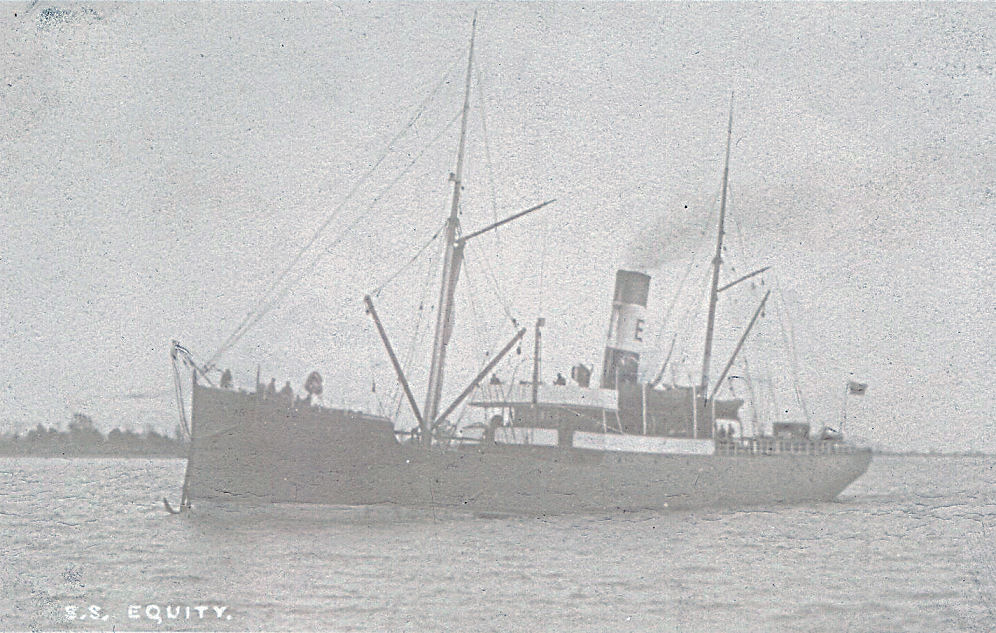

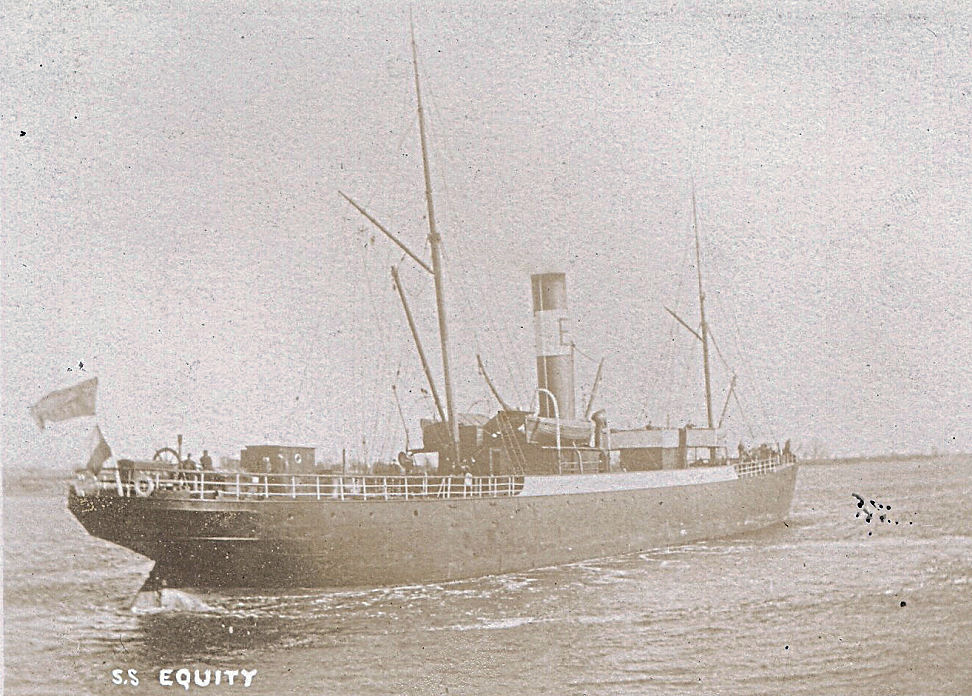

In the autumn of 1917 the first Jaegers returned to Finland. This first group consisted of eight infantrymen and arrived in a cargo-ship named the Equity, whose commander was Jaeger Lieutenant Gustav Petzold. Built in 1888 by Earle’s Shipbuilding & Engineering, Hull (UK), the S/S Equity was a German ship, which had been captured from the British in the port of Hamburg in August 1914. She then served as a German Army Transport under the names “Olaf”, “Adolph Ardessen” and “Mira.” Following WW1, the Equity was returned to her owners in 1918. She survived a wreck on Alderney in 1920 after leaving Goole, Jersey for Hull on 27 May 1920 with a cargo of potatoes. She was refloated by the salvage steamer Ranger and after repairs, resumed working life. She was broken up at Grangemouth on December 1931. See here for source).

The S/S Equity carried a cargo of weapons and ammunition (7,000 Rifles, 2,600,000 cartridges and 4,500 grenades) which were landed on Nov. 2nd 1917 in the islands of the Larsmo archipelago near Vaasa and Pietarsaaren (a memorial is now in place at Tolvmangrundet island commemorating this event). More about the Equity’s trips can be found in KG Olins book “Tärningskast på Liv och Död” (“Dice Roll of Life and Death”). (Many thanks to the grog blog for a few of these tidbits and links to the photos of the Equity).

A second voyage by the Equity failed. Between the two different voyages by the Equity, eight Jaegers arrived in the German submarine UC 57 and were landed in Loviisa with weapons and explosives. On the way back the submarine UC 57 was destroyed. Towards the end of 1917 and beginning of 1918, other small groups of Jaegers arrived in Finland. On 6 December 1917, the Finnish declaration of independence indicated that the time for the return of the Jaegers to Finland had arrived.

The Germans delayed the return of the Jaegers to avoid complications between Russia and Germany as the Brest-Litovsk peace negotiations were in progress and would be compromised. The situation was clarified, and the Russian Bolshevik government advised Germany that Russia recognized Finland’s independence. Now the return of the Jaegers could not be regarded as an act of hostility towards Russia.

The German Ministry of War ordered the disbanding of Jaeger Battalion 27 from the German Army on the 5th February 1918. The new commander of the Jaegers was Finnish Lieutenant Colonel Wilhelm Thesleff, who arrived Libau representing the Finnish government. The Jaegers signed a commitment to serve in the Finnish army for at least one year, and they received Finnish military ranks.

Finland had gained its independence and the Finnish Army had gained 403 officers and 727 non-commissioned officers, all with military experience and training. This would be of the utmost importance to Finland’s future as the country headed towards Civil War, with the Jaegers forming the nucleus of the nascent Finnish Army.

Arrival at Vaasa – 25 February 1918 02.25.1918

The battalion held a dawn parade on the morning of 13 February 1918 were the battalion commander, Captain Ausfeldt read orders regarding the change of command and made a farewell speech. The battalion’s flag was consecrated in Libau (Liepāja) at the Holy Trinity church. The Jaegers swore a military oath to Finland’s legitimate government. before the Jaegers could return to Finland, the Civil War began. This led to fears that the Jaegers could break into two camps.

These fears proved unfounded, as almost all supported the legitimate government (the Finnish Whites). While the main body of Jaegers returned to Finland, some 400 men were left behind in Germany for various reasons. Most of them were in civilian jobs, while some were in hospital or recuperating. The majority of these men returned to Finland over the remainder of 1918 and 1919. The vanguard of the Jaegers, 85 men under the leadership of Major Harald Öhquist, arrived in Vaasa on 18 February on the S/S Mira (actually the S/S Equity under a German name) and the S/S Poseidon.

The main body of the Jaegers left the port of Libau (Liepāja) for Finland in 14th February. The S/S Arcturus, which carried them, was bursting at the seams with its cargo of 854 Jaegers. The cargo ship Castor carried a further 96 Jaegers, with a total force of Jääkärien of 950 men.

The Finnish icebreaker Sampo helped the ships make the final entrance into Vaasa, where they arrived on 25 February 1918, three years to the day after the first Pfadfinder had arrived in Lockstedt. On the 26th of February, the Jaegers held their last joint parade for the new Commander-in-Chief, General Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, in the market square of Vaasa. General Mannerheim emphasized the great and glorious task awaiting the Jaegers, after which they were dispersed to new jobs throughout the government forces of White Finland.

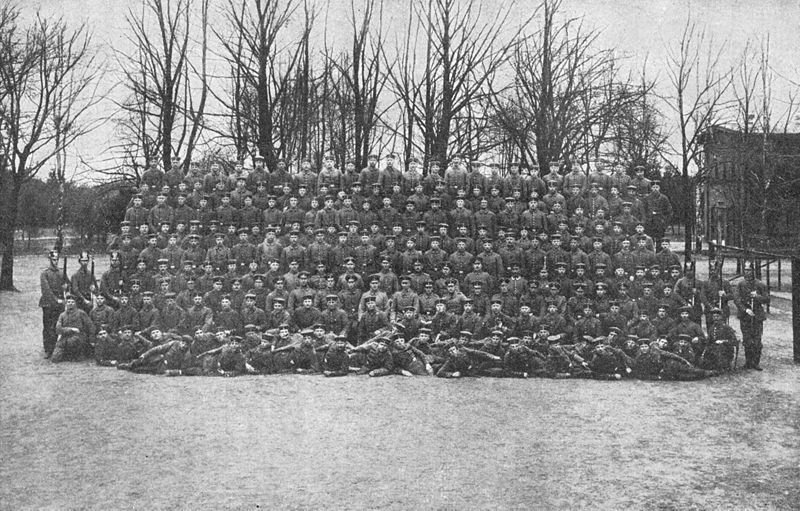

The last parade of Jaeger Battalion 27 in Vaasa at the market square on 26/Feb/1918. General Mannerheim inspects the battalion.

The Finnish Civil War of 1918 and the Jaegers

After the October Revolution of 1917 in Russia, subversive activity began to increase in Finland. A general strike in November 1917 deepened the suspicions and mistrust between the “Reds” and the “Whites” and both sides began moving to defend themselves. At the same time, communists and left-wing socialists were now considering overthrowing the democratically elected government by military force. In December 1917, Finland gained her independence but in January 1918 there were still 65,000 Russian soldiers in Finland, of whom several thousand actively supported the Finnish Reds. The final escalation towards civil war began in early January 1918.

The Finnish Senate and Parliament decided on 12 January 1918 to create a strong police force, an initiative which the Red Guards saw as forestalling their planned seizure of power by force. On 15 January, General Mannerheim, a former general of the Imperial Russian Army, was appointed supreme commander of the White Guards, and on 25 January the Senate appointed the White Guards as the Finnish White Army. The Red Guards refused to recognise the title, and decided to establish a military authority of their own. General Mannerheim located his headquarters in Vaasa, while Aaltonen, the commander of the Finnish Red Guards, located his headquarters in Helsinki. The civil war had begun.

The first serious local battles were fought during 9–21 January in southern and southeastern Finland. The Helsinki Guard, the strongest Red unit with its crucial strategic position in the capital of Finland had already become active on 23–25 January, aiming to secure a major power base for the Reds. The White order to engage was issued on 25 January, and the Red Order of Revolution was issued on 26 January 1918. The large scale mobilization of the Red Guards began in the late evening of 27 January. The Red Guards held the initiative at the start of the Civil War, holding Helsinki, the industrial city of Tampere and the ports of Turku and Viipuri. However, while well-armed and with no shortage of volunteers, they lacked leaders with any military knowledge and the command structure was weak to non-existent.

The arrival of the Finnish Jaegers at Vaasa gave the White Army a huge advantage in the civil war. The Jaegers were highly trained and had experienced combat on the eastern front. In addition, almost all the Jaegers were trained as either Officers or NCO’s and when distributed throughout the White forces, provided strong and skilled leadership that made disciplined action and coordination possible. Three of the Jaeger Officers were appointed to command Brigades – Colonels Eduard Ausfeldt and Ulrich von Coler, as well as Major Rainer Stahel. All six Jaeger Regiment commanders, and all but one of the Battalion commanders for 18 regiments of infantry were Jaegers – these commanders had mostly received Platoon leader training in Germany. Most of the Jaegers worked as Trainers, then as Company or Platoon Commanders.

Many of the Jaegers took on far more demanding tasks than those for which they had been trained. Colonel Aarne Sihvo was appointed Karelian front commander and his chief of staff was Lieutenant Colonel Woldemar Hägglund. Sihvo was 28 years old, while Hägglund was 24 years old. Jaegers were, above all, in positions of command at the front and served as an example to their men, being given extensive latitude to lead the fighting . Jaeger losses were very heavy in the Civil War, with 127 dead and 238 wounded. Their contribution to the White victory and the preservation of Finland’s independence was crucial. They formed the backbone and spiritual spine of the newly independent state’s Army.

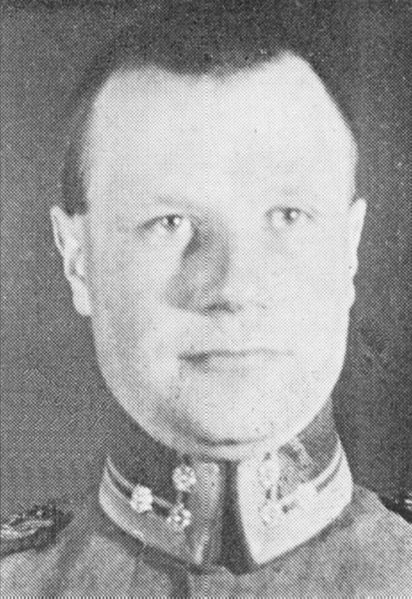

Colonel Aarne Sihvo chief of staff, Lieutenant-Colonel Woldemar Hagglund commanded the war effort on the Karelian front

Victory War 16 May 1918 in Helsinki. General Mannerheim, riding at the head of the Finnish White Army.

Immediately after the Civil War, the Finnish Jaegers were given the right to use the word Jäger in their military ranks. Many of the Jägers continued their military careers. In the 1920’s a long feud between officers with Jäger-background and Finnish officers who had served in the Russian Imperial army was concluded in favor of the Jägers: Most of the commanders of army corps, divisions and regiments in the Winter War were Jägers. The Jäger March composed by Jean Sibelius to the words written by the Jäger Heikki Nurmio, became the honorary march of many army detachments.

The “Jäger conflict” in the 1920’s

The Jäger conflict derived from the German influenced Jägers and politicians that saw Germany as their ally in conflict with the Swedish-Entente orientated circles around the former Russian General and Finnish Commander-in-Chief Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim. Mannerheim and the Swedish officers of the Finnish Army left Finland as a direct cause of this conflict and the Finnish Senate elected a German prince as King of Finland and would have made Finland a Monarchy. When the World War ended and the Kaiser fled, the Finnish monarchy was replaced by the Finnish Republic and a vindicated Mannerheim returned as Regent of Finland.

The Jägers played a key role in the Finnish Army from its formation through to, and in many cases after, the Winter War World War 2. By the time of the Winter War, “Jäger” Officers held most of the senior positions in Army Headquarters as well as commanding almost all of the Divisions and Regiments of which the Army was made up. While mostly junior Officers in the 1920’s, the Jägers gradually assumed higher ranks and held more and more key positions as time passed and older Officers retired. It was these Jäger Officers who were instrumental in carrying out the training and organizational reforms of the 1930’s. It was these Jäger Officers who drove the innovative weapons research and design programs of the 1930’s.

It was these Jäger Officers who were instrumental in developing the combat doctrine and tactics that, man for man, made the Suomen Armeija (Finnish Army) into what was arguably the best combat army of World War 2, with an effectiveness out of all proportion to the small size of the Army and the Country. It was these Jäger Officers whose dedication over the course of two decades to the ongoing development of Finland’s defense capabilities led to the Finnish victories of the Winter War and of the Finnish Army in the later part of the Second World War.

As such, before we go any further, we should take a closer look at the “Jägers” and their place in the Finnish Army (Suomen Armeija) through the 1920’s and 1930’s.

And a note on sources: the bulk of the written material below relies on a PhD Thesis, “Soldiering and the Making of Finnish Manhood” by ANDERS AHLBÄCK, ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY, 2010 as the source. The entire thesis covers wide-ranging ground over the period 1918-1939 and, being in English, is a fount of information to the non-Finn on military service in Finland over this period. Illustrations and music are my own additions as is some of the interpretation and commentary here and there. Any mistakes in interpretation are my own.

The Jägers and the “Russians”

The Finnish Cadre / Conscript Army grew out of the long shadow cast by the Civil War. The senior officers in charge of the emergence of the military system in interwar Finland were a combination of nationalist activists who had prepared for a war of independence from Russia and who had trained and fought under German command, and professional officers from the former Tsarist-Russian Army who had returned to Finland after the Bolshevik Revolution. These groups mobilised and organised the White Army in 1918, and led its development into a modern national armed force. Of these disparate political and generational factions, one group in particular stands out as decisive in the formation of the Finnish Army. This group was that of the so-called Jäger officers, the war heroes of the “Liberation War” whose story we have read above.

The story usually told about the Jägers in interwar Finland described them as young militant activists for independence who had clandestinely left Finland for Germany during the First World War, defecting to the Russian Empire’s enemy by the hundreds. Seizing the unique opportunity provided by the Great War, they sought military training in order to lead a planned popular insurgence to liberate Finland from Russia. The Jägers then returned to Finland to fight in the Civil War, training the government’s new conscripted troops and leading them into battle. Contemporaries thought their thorough German military training, fresh combat experience of modern warfare, and patriotic zeal was crucial to the striking power and final victory of the White Army in 1918.

The story of the Jägers’ conveyed an image of what the Finnish soldier should and could be like. The living reality and presence of the Jägers throughout the army organisation made their example something more than a distant and lofty ideal. In the 1920’s, a good number of the training officers as well as the company and regimental commanders of the conscript army were Jäger veterans. They were flesh-and-blood, leading much of the practical military education of Finnish conscripts at the company and regimental level and serving as ever-present real-life models for the conscripts. Jäger officers led the institutions for officer training, from the Reserve Officer School to the Cadet School and the National War College. Towards the end of the 1920’s and even more so through the 1930’s, they came to dominate the senior positions in the armed forces and thus the central planning and organisation of the Conscripts military training. In the post-war flood of historical works, memoirs, novels and magazine articles about the events of the Civil War, the story of the Jägers who risked everything to save their country was repeatedly and actively told and retold, not least by their supporters and by the Jägers themselves.

The story of the Jägers became part of the mythic telling of the Civil War, conveying a deep moral message

The story of the Jägers became part of the mythic telling of the Civil War, conveying a deep moral message, but also meeting the psychological needs of post-war society. In their patriotic grandeur the accounts were probably far removed from the private war memories of many people, especially those on the “red” side. Forming a kind of master narrative, the Jäger myth obscured many other viewpoints of the Finnish Civil War experience. These obscured viewpoints were not only the voices of the socialists and “workers” who lost the Civil War, but also those of the professional officers who had served the Russian Tsar, the Jägers disabled in the war, and the Jägers who found themselves unemployed and in misery in a post-war society. Nevertheless, the Jäger story offered a perception of history that not only served the state’s purposes, but obviously appealed to many Finns – perhaps even more so to young people who had no personal experiences or only dim childhood memories of the war. To the extent that the Jäger stories permeated Finnish society ever more deeply, the stories also provided an image of the Finnish military for Conscripts to base their own expectations on.

The rest of this Chapter is a study of how the Jägers public image in Finland in the 1920’s and 1930’s, together with the stories told about their achievements and the character of the Jägers themselves, helped to create an image of the Finnish Soldier within Finnish Society. It was in many ways this societal image which set the standard for Conscripts and formed a solid psychological foundation for the soldiers of the Winter War. The PhD thesis from which this analysis has been taken draws on a range of sources; histories of the Liberation War and the Jäger Movement published shortly after the war, memoirs by individual Jägers, Suomen Sotilas (the army’s magazine for soldiers) and the yearly Christmas magazine Jääkäri-Invaliidi (The Jäger Invalid), published by the Jäger Association and sold for the benefit of Jäger veterans who were invalids.

The first section looks at how the “heroic Jäger” image was built up. The second section will look at how the “heroic Jäger” image was used in a campaign to oust former officers of the Russian Imperial Army and pave the way for the Jägers to obtain leading positions in the Armed Forces. Here, some newspaper and magazine articles were used as sources. However, as Jääkäri-invaliidi and the internal newsletter of the Jäger association Parole make visible, not all Jägers who survived the war became successful career officers. The experiences of less fortunate Jägers add an interesting contrast to the imagery of the successful war heroes.

In the third section, the military education agenda of the Jäger officers, as it was expressed in military regulations and handbooks of the late 1920’s and 1930’s, is investigated as regards the images created of the Finnish soldier and the connection of this to the Jägers’ ideals and self-image. In the concluding section, the functions and purposes of the Jägers as a military image held up to be emulated and aspired to are discussed.

How the image of the “Heroic Jäger” was built up

A great number of historical and fictional works, articles and short stories in magazines and periodicals, memoirs and even stage plays and motion pictures were produced in the interwar era to commemorate the Jäger movement and the vicissitudes of the Jägers’ journeys, military training and war experiences during the Great War and the Liberation War. All this commemoration can be seen to have served a number of different purposes. Perhaps the most immediate one was to vindicate these militant activists for independence against all those who had thought they were immature and foolhardy adventurers who had put the whole nation at risk, or even thought that their actions constituted treason. Other purposes were to invest the horrific civil war with a positive meaning, turning a national tragedy into a national triumph, and to create an image of the “ideal” Finnish Soldier for all those Conscripts who were now called up to defend the new Finnish state.

In order to understand how the Jägers were portrayed as soldiers, and what kind of image was conveyed, consideration must be given to how the Jägers portrayed the righteousness of their cause and how they ascribed the Civil War with a special meaning. This section will first provide the historical background for the Jäger movement, then highlight the characteristics by which the Jägers were portrayed as war heroes; their energy and ability to act, their youthfulness and passionate nature, their patriotic zeal and spirit of self sacrifice, and their unflinching faith in victory, beyond rationality or consideration. The Jägers’ “war heroism” should be seen against the backdrop of a process of transformation within Finnish nationalism during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Finnish nationalism in the nineteenth century had primarily celebrated Finnish language and culture and emphasised the peaceful advancement of national culture and prosperity through popular enlightenment, legal rule, and domestic autonomy. The heroes of the national pantheon had mainly been poets, philologists, composers and political philosophers. Due to Finland’s position as a part of the autocratically ruled Russian Empire, expressions of Finnish patriotism had to be carefully expressed. The main military heroes of the era were the semi-fictional characters of Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s poem Tales of Ensign Stål (1–2, 1848 and 1860) and Zacharias Topelius’ serial story Tales of an Army Surgeon (1853–1867), both immensely popular works that certainly provided role models for the Finnish Soldier.

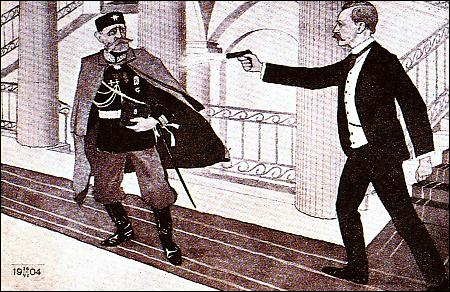

A new militancy within Finnish nationalism came into existence around 1900, for the first time it was suggested that military force could be a useful way of promoting Finland’s national interest in relation to the Russian Empire. According to historian Nils-Erik Villstrand, this period constituted a turning point, where Finland suddenly diverged from a common Nordic political culture of non-violence, dialogue and mutual adjustment. Influenced by Russian opposition groups, Finnish independence activists and socialists incorporated political violence into their arsenal. A Finnish underground activist movement started to form in 1901, in order to resist the Russian suppression of Finnish autonomy. It co-operated with revolutionary movements in Russia, distributed illegal literature and press, opposed the draft under the new military service law of 1901 and organised political agitation among the population. In 1902–1903, parts of the resistance movement were radicalized and adopted terrorist methods, including political assassinations, for restoring “lawfulness” and full Finnish autonomy. The early activism of 1901–1905 soon dissolved as a consequence of the Russian government’s political concessions in the wake of the Russian Revolution in 1905. The widening rift between Finnish socialist and non-socialist civic activists also contributed to the dissolving of this movement.

The assassination of the detested Russian Governor-General of Finland, Nikolai Bobrikov by Eugen Schauman in June 1904. Schauman’s sister lived a long life — she was a talented painter and an art critic — and wrote a loving memoir of him, long out of print and only available in Swedish. One of the great ironies of Schauman’s rebellious, short life is that, while he is a Finnish national hero, his family spoke Swedish — and Russian, because his father, like Bobrikov, was an officer in the Imperial Russian Army.

The so-called early activists organised shooting practices and aimed at arming “patriotic” citizens. Yet even they did not necessarily see independence as a viable option. One concern was that the military burdens of an independent state would be too heavy for Finland to carry. As long as the Russian monarchy was in place, opinions in Finland remained deeply divided over whether resistance should be active or passive and whether the Finns should seek confrontation or reconciliation with the Russian government. A majority of Finns remained loyal to Russia at the outbreak of the Great War. Over one thousand conscripts volunteered to fight in the Russian army.

Yet according to historian Tuomas Hoppu, no evidence can be found that these men volunteered for the cause of Russia or the empire. Rather, their motivation ranged from a poor social position and a desire to secure their own and their families’ livelihood, to love of adventure and a wish to see the world and gain career opportunities. In spite of formal loyalty, Hoppu writes, the public opinion in Finland was negative to Finns serving in the Russian forces, and for this reason several hundred volunteers changed their mind and stayed at home.

The founding of the Jäger movement

Bourgeois Swedish-speaking “old activists”, nationalist veterans of the activism of 1902–1905, immediately recognised a potential ally in Germany in 1914; an ally not only against the common Russian adversary, but also against the ever-strengthening socialist movement and the growing threat of social revolution in Finland. The Germans for their part had a strategic interest in inciting a rebellion against Russian rule in Finland. Contacts between exiled Finnish activists in Stockholm and the German military command were soon established. The older activists joined forces with a younger generation of leaders of both Swedish and Finnish-speaking nationalist student circles in Helsinki, who had also been scheming for Finnish independence with support from either Sweden or Germany. These students were frustrated with what they thought of as the compliance and outmoded clinging to legality of the older generation of Finnish nationalists in the struggle to defend Finnish autonomy against Russian authorities. The educated youth in 1914 was “trembling with a vague desire to do something and was only looking for a form of action which would sufficiently satisfy its glowing hatred of the oppressors”, wrote Pehr Herman Norrmén (1894–1945), one of the earliest Jäger activists, in an early history of the movement in 1918.

According to historian Matti Klinge, an admiration of the new German Kaiserreich and its science, economy and military strength had grown among Finland’s educated elites during the decade before the Great War. A current of Germanism, starting primarily among conscripts of the largely Swedish-speaking upper classes, celebrated activism, sports, and notions of “Germanic energy”. Force, action and intuition were seen as superior to rationalism and empiricism. For young men attracted by this cult of action, the option of sitting out a world war in peaceful Helsinki, while other nations seemingly fought over the future of Western civilisation, must have seemed shameful. By contrast, the alternative of joining forces with the admired Germans had an allure of adventure in spite of – or maybe indeed because of – the dangers involved and the foolhardiness of the whole venture. P.H. Norrmén described what happened as a forceful “emotional reaction” against the paralyzing sentiment of passivity in Finnish society. He remembered how “passionately” the young students longed for some action that would “wake up the sleepers, force the hesitant to act”. The students decided it was time to ignite a national rebellion in Finland. To lead that rebellion, the students needed military education.

A group of Finnish Volunteers, many of whom would later become Senior Officers in the Suomen Maavoimat and play an important role in the Miracle of the Winter War

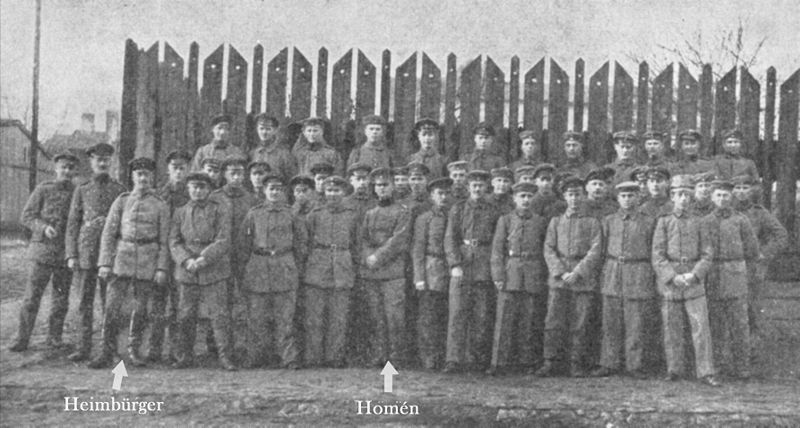

Officers of the Royal Prussian 27th Jäger Battalion (Königlich Preussisches Jägerbataillon Nr. 27) in Liepāja (Libau) in 1917

Jääkäripataljoona 27:n päällystöä Liepājassa (Libau) syksyllä 1917.

Alin rivi: Oberzugf. Hugo Österman, zugf. Eric Schauman, oberzugf. Gabriel von Bonsdorff, zugf. Paul Ljungberg, oberzugf. Karl Mandelin, zugf. Einar Johansson.

Keskimmäinen rivi: luutnantti Franzen, luutnantti Huyssen, luutnantti Rüets, kapteeni Ulrich von Coler, kapteeni Eduard Ausfeld, tohtori Valter Sivén, yliluutnantti Stahel, Luutnantti Albert Mellis, luutnantti Könnecke, tohtori Yrjö Salminen.

Ylin rivi: oberzugf. Lauri Malmberg, oberzugf. Maximilian Savonius, oberzugf. Erik Heinrichs, oberzugf. Harald Öhquist, talouspäällikkö Arp, hauptzugf. Torsten Jernström, zugf. Torsten Lesch, oberzugf. Karl Oesch, zugf. Knut Solin, tohtori Häberle, zugf. Lars Homén, zugf. Jarl Taucher.

In February 1915, the Germans agreed to give military training to a group of 200 Finnish activists. Whether the initiative was actually made by older Finnish activists in Sweden, German intelligence or university students in Helsinki is a matter of controversy – the Jägers themselves later claimed the latter. The leaders of the “passive” resistance against Russian imperial policies in Finland, i.e. the majority of older Finnish politicians, flatly opposed the plans, but the activists were not impressed by their objections. Volunteers travelled to Sweden under different pretexts and then continued to Germany and a training camp of the German army at Lockstedt in the Hamburg region. During 1915 and 1916, the original training unit of 189 men, consisting mainly of Swedish-speaking university students or graduates from Helsinki, was slowly enlarged through secret recruitment in Finland to a battalion comprising almost 1900 men. Students and workers eventually constituted the two main groups of the Finnish Jäger battalion at the Lockstedter Lager. The majority of the enlarged battalion were Finnish-speaking men from the lower social strata; 34% were farmer’s sons and 26% sons of workers. Nonetheless, those with a father in an academic profession were over-represented at 8%.

As we have read, the battalion underwent austere Prussian military training at the Lockstedter Lager, suffering from prolonged uncertainty over their future and the German military command’s intentions as well as hunger due to the general food shortage in the belligerent Reich. As the envisioned German landing operation in Finland was postponed indefinitely, the Finnish battalion was deployed on the German Eastern Front in Latvia and Lithuania to get battlefield experience. There, the Jägers endured trench warfare and Russian shelling, but only a few instances of actual combat. In the Jäger histories, the Jägers’ growing despair as to whether they would ever be able to return home was usually depicted as much harder to bear than the hardships of life at the front. Only in February 1918, after Russia had been shaken by two revolutions, and after Finland had declared independence in December 1917 and with the interior situation in Finland deteriorating into civil war, did the German military command finally decide to send the Jägers back to join the Finnish government forces.

The Jägers gave elementary military training to tens of thousands of volunteers and conscripts and led these troops into battle. The victory of the government troops in May 1918 was perhaps hastened by the German intervention in April. Nevertheless, the military expertise and leadership of the Jägers was often identified in contemporary accounts as a decisive advantage of the “White” Army over the well equipped but poorly trained “Red” troops. According to the historian and politician Eirik Hornborg (1879–1965) – himself a Jäger – the most important thing about the Jägers was not their numbers, 400 officers and 700 non-commissioned officers, but their standing as seasoned warriors in a country hitherto untouched by the Great War. “[A] Jäger was a legendary figure who enjoyed the blind confidence of his men, whether he actually deserved it or not”.

Sievi Holmberg, who worked as a nurse for the Whites, described Jäger officer Veikko Läheniemi, commanding the white forces in her sector, as a man who “despite his modest appearance arouses horror in the enemy, unlimited admiration and respect in his own boys, and with his personal courage shows his boys that “a real man can only fall, not yield to danger.” The Swedish Colonel W.A. Douglas, who participated in the Finnish civil war, later remembered “the Jägers enjoyed an almost supernatural trust among the nationally minded public in Finland.”

A heroic story of national liberation

The gaining of independence to a certain extent vindicated the activists who for years had plotted and agitated for armed resistance against the Russian Empire. Yet how to construct the national self-image in the wake of 1918 was problematic. Finland never really participated in the Great War, but neither could the country identify with the self-image of a peace-loving neutral nation either, since it had the memories of its own short but cruel civil war to deal with. Finland’s independence had above all been made possible by the Russian military defeat by Germany and the subsequent Russian revolutions. Only after power in Russia had fallen into the hands of socialist revolutionaries did the Finnish bourgeoisie unanimously rally around the idea of national independence. The bitter class conflict within the Finnish population itself almost undid independence just as it had been declared. German weapons deliveries and a German military intervention to support the Finnish government in the Civil War had a major impact on the outcome of the Civil War. Historian Matti Lackman has pointed out that the activists and politicians inviting German troops to Finland took a great risk. The country would in all likeliehood have become a vassal state of the Reich, had not Germany been defeated by the Entente soon after.

The Jägers, however, provided ample material for anybody who wanted to tell a heroic and edifying story about how Finland gained its independence. Their story had all the elements of a good adventure tale; Finland’s desperate situation at the hands of the Russian oppressors, the passivity and resignation of the older generations, the insuppressible longing for deeds and action among a young elite, the dangerous journey into the unknown, the hardships and privations of draconian Prussian military training, the baptism of fire on the Eastern Front, the nerve-racking waiting for a decisive turn in events, and eventually the triumphant return to the native country and the final victorious battle against Finland’s enemies.

In 1933, Yrjö Ruutu (1887–1956) published an article in the Jääkäriinvaliidi magazine, commemorating the 15th anniversary of the “Liberation War”, which is an interesting example of how the Jägers could be used to make claims about the war and the entire Finnish nation. Ruutu was the president of the students’ union in 1914 and one of the earliest organisers of the Jäger movement. He acquired a standing as a kind of theorist and ideologue of the movement. Among the different means for achieving independence, Ruutu wrote, the Jäger movement had been the most important. “The Finns’ own influence on their country’s future hang on its success more than on anything else.” Behind this movement stood members of all social classes and parties and thus it represented the whole Finnish society, claimed Ruutu. “Its existence was proof that the will for independence of the Finnish people had gone from words and wishes to actions.” The Jäger movement had demonstrated that the Finnish people did not want to “sit around arms crossed” in the middle of a World War, waiting for others to act and to help, but that the people of this nation wanted to take responsibility for its own destiny. In Ruutu’s mind, the Jäger movement was proof of Finland’s coming of age as a state.

Similar portrayals of the Jäger movement could be found in the conservative and right-wing press on the anniversary of the Jägers’ return to Finland that same year, February 25th, 1933. Ajan Suunta, the daily newspaper of the far-right Isänmaallinen Kansanliike (Patriotic People’s Movement) wrote about the conscripts who had been ”the avengers of their people”; who wielded ”a sword hardened in fire and blood in strong hands”. The open armed struggle of Finnish youth against the oppressor in the Great War was a beacon for the people, stated Ajan Suunta. “The shining example of a thousand conscripts was the igniting spark that lit into enormous flames the eternal fire of patriotism”. The conservative daily Uusi Suomi was not quite as carried away, but wrote: “Many peoples could envy us for the hero story of the Jägers. … They roused the spirit of the liberation war, years before its hour had come, and maintained it during years of seeming hopelessness, in spite of the warnings and accusations of old people and although “the people and the country hung their heads” … The Jäger story is a national treasure. It is an inspiring model and source of faith for Finnish youth for all times to come. It is one of the most durable keystones of our future.”

Thus, a small group of young idealists mounting illegal military action against the old regime were offered as the evidence of national maturity. The strength of their passion and valour was seen by Ruutu and other nonsocialist commentators as an indicator of how the “Finnish people” had developed a patriotism strong enough to sustain an independent state. The Jägers springing into action, doing something daring and magnificent, made it possible for nationalist rhetoric to gloss over the image of a nation passively awaiting its destiny at the hands of foreign armies with the far more preferable image of the Finnish nation as strong, energetic and capable of decisive action. Similar to how the Jägers had appeared on the battlefields as armed and trained soldiers, Finland had now emerged on the world-scene as a sovereign state, armed, ready and able to defend itself. The nation had finally reached the threshold and passed the necessary trial of statehood in war. “The new free state was born with the attitude of the freedom fight”, wrote the prominent Jäger officer, publicist, military historian and military educator Heikki Nurmio (1887–1947) in 1923, thus triumphantly concluding a lyrical description of the Jägers’ journey over dangerous waters to return home to Finland in February 1918. True independence can only be attained through struggle and fight, maintained the chairman of the Jäger Association Verner Gustafsson in 1938.

Another frequent variation on this theme was that the Jägers had rekindled “the spirit of the forefathers” and thus renewed a centuries-old alleged tradition in which “the Finnish man has fought for his country or valiantly marched for faith, freedom and fatherland”, especially against “the evil East”. In this version, then, the strong, bold and Jägers evoked the memories of their Finnish forefathers, linking the modern nation to a mythical past. The Jägers’ role had been to energise a nation that had lost its vigour and valour through Russian oppression, the lack of national armed forces and the anxiousness of old men clutching on to lawbooks instead of taking up the sword. This rhetoric probably corresponded to how the Jägers had personally experienced the situation in 1914–1915; the suffocating cautiousness and passivity of the older generations and their own youthful urge for action. P.H. Norrmén wrote in 1918 of his “lively recollection” of a night in October 1914 as students in a nightly gathering in Helsinki burst out singing Die Wacht am Rhein “seized with a crazy enthusiasm … without damping and without precaution, just for the joy of defying the prevailing sentiment of old men’s wariness.”

Die Wacht am Rhein

These angry young men longed for armed action and were “embittered by the know-all attitude of voices trying to subdue the rising fighting spirit in our people”. They were thus confronted with a widespread reluctance against military violence among the Finnish educated classes that only deepened as the Great War raged on. However, as we have seen, the Civil War brought a decisive shift towards the new kind of militarised nationalism represented by the Jägers.

Youthfulness and Passion in the Jäger story

The youthfulness and youthful passion of the Jägers was often emphasised. In his documentary book Diary of a Jäger (1918), published soon after the Civil War, Heikki Nurmio described how three teenage boys came to see him in 1915, eager to leave for Germany. As their high school teacher at the time, Nurmio tried to talk them out of it, but failed. He commented: “Who can still a storm with rebukes. The storms of spring take their own course; they crush the chains of nature, as if for fun, with their irresistible force. In those youths, under their seemingly tranquil surface, the storms of spring were raging and already doing their irresistible work.” This passionate desire for action and deeds among the young generation was juxtaposed with the cautiousness and passivity of the older generation in the stage play Jääkärit (The Jägers, 1933), written by Jäger Major Leonard Grandell (1894–1967) and bestselling author Kersti Bergroth (1886–1975). In the play, young Arvo who is secretly preparing to travel to the Jäger training camp in Germany bursts out angrily at his father, who adamantly abides by legality in the face of the Russian imperial authorities’ suppression of Finland’s autonomy: “A young person will do foolish things if he is not allowed to fight. (…) A young person cannot control himself – but maybe he can control the world. Let us fight outwards, that suits us. And let us fight in our way.” At the end of the play, as Arvo returns as a Jäger officer and the liberator of his own village from the socialist revolutionaries, his father admits: “I say, it was a great idea, this strange deed of the boys. Where did they get it, immature children? It took us old people years to even understand it. To them it just came ready-made – out of somewhere!”

The Jäger youth was thus associated with energy and action and contrasted to the passivity of the older men of compliance. The foolhardiness, adventurousness and even recklessness of their enterprise, characteristics that would have been scorned by middle-aged moralists in most other contexts, were celebrated as admirable virtues. Youth and strong passions were closely connected to each other in nineteenth and early twentieth century bourgeois discourses on manliness and morality. However, in the “self-help books” for conscripts of the era, as studied by historian David Tjeder, the passions were seen as a threat and a problem, something that a young man had to learn to master, control and suppress, lest they bring his downfall into a life of vice. Self-discipline, self-restraint and building a “strong character” were emphasised. However, this was not the case in the Jäger narratives. There, the passion of youth became a historic force as it was channelled into flaming patriotism. The demands of warfare in an era of national states transformed the bourgeois ideals of manliness. The national warrior of the Liberation War certainly had to know how to master his desires and his fear. However, according to the Jäger narratives, even more than that he must be able to devote himself, give himself up to great and noble emotions, push vapid circumspection aside and just passionately believe in his own and his nation’s ability to fight and to triumph.

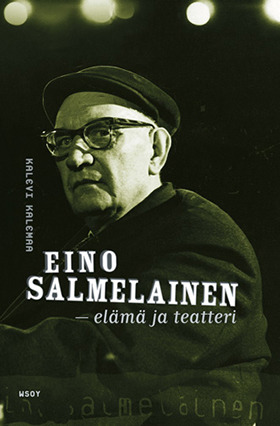

In some stories, individual Jägers could be portrayed as reckless adolescents rather than real men upon leaving home for the great adventure. The journalist and former student of theology Eino Salmelainen (1893–1975) depicted the fictional main character of his 1922 short story ‘How Rudolf Borg became a Jäger’ as an unusual and precocious adolescent who was ill-adjusted to his school environment, did not care for schoolwork and made his parents very concerned. Borg leaves for Jäger training in Germany and returns transformed. He “fights like a man” in 1918, but the narrator of the short story asks whatever would have become of the boy if he had not found his calling in soldiering and the Jäger movement. “The brave and gallant officer’s dress still hid within it more of a daredevil boy than a man. After the war, life here once more began to feel too plain and ordinary. Then the battlefields of Estonia and [Eastern Karelia] could for their part bring his restless mind gratification.” The story nevertheless ends with a depiction of how Rudolf Borg visits his home town as a stately officer. His previous schoolmates who had made fun of him are now shy of him, not knowing what to say in their awe of him. His father, however, is proud to walk beside him in town: “He felt that his boy had now become a man.”

In narratives such as the stage play Jääkärit or the short story about Rudolf Borg, military training, war experience and the duties of an officer channelled the foolhardiness and passion of youth and gave them forms respected and appreciated by society. Both stories implicitly states that when the nation was in danger and deeds were needed, the passionate nature of young masculinity was transformed from a problem in normal peacetime society into a rescuing resource in times of crises. At the same time, war and noble action gave the passions of youth the possibility of being discharged in order to benefit of society. Most of the Jägers were between 20 and 25 years old when they enlisted. There were some teenage boys among them, who more or less ran away from home to join the battalion, but there were also older men in their 30’s. However, the people actually taking the real decisions within the Jäger movement – apart from the German military command – were the older generation of middle-age, upper-class activists in Helsinki, Stockholm and Berlin – Interestingly, their significance was later played down in the heroic story-telling, perhaps because it did not fit into the dramaturgy of the youthful hero myth.

The heroic virtue of self-sacrifice

Despite all their daredevilry, adventurousness and passion, the Jägers were also depicted as models of the supreme nationalist virtue, the spirit of self-sacrifice. Although most of the Jägers survived the war and many became distinguished figures in post-war society, over 10% of the 1300 Jägers who returned to fight in the Civil War were killed or mortally wounded in action. The Jägers who died and “gave more than all others” were thus an important though not a dominant part of the Jäger story, however, it was once again their youth that was especially emphasised. In the poem “The young Jäger” by Aarne Mustasalo (a nom de plume used by Heikki Nurmio) published in 1924, the “young hero” is lying mortally wounded on a stretcher, “his pale face noble and beautiful”, feeling the burning pain in his wound and death calling him. Through the treetops sound “songs of heroes immortal … over Finland, sounding in every young and brave heart, raising the troops with shining eyes. – From heart to heart, the song is one, the faith is one: the fatherland calls!” This poem was dedicated to the memory of Jäger Second Lieutenant Ahti Karppinen who was killed when the city of Viipuri was captured in one of the very last battles of the Civil War.

Another poem published in 1921, written by Artturi Leinonen, who himself had tried to join the Jägers in Germany, but been intercepted by Russian police, also gave expression to the cult of the youthful, passionate and self-sacrificing national warrior. This cult was not limited to the Jägers, but included all the allegedly voluntary and self-sacrificial soldiers of the White Army – yet as the leaders of other soldiers, the Jägers were fallen heroes on a higher level. Leinonen’s poem “The young hero” describes an unspecified white soldier hit by a bullet in the head, lying in the snow and feeling death approaching:

(…) Like a child, exhausted and fallen asleep

he lies on the glistering snow.

What moment loveliest in life?

That, which ignites the heart

brings it to an intense glow, to a holy fire.

When a man, forgetting himself

Only directs his strength to what is great and noble.

When he gives everything he can give.

Who brought a young life as a sacrifice

he gave more than all others.

As long as the stars and moons wander

As long as new days break to dawn

The word hero will honour his memory