The ANZAC Volunteer Battalion in the Winter War

On the outbreak of the Winter War between Finland and the USSR, in a flurry of telegrams and long distance calls between Colonel Hunter (whom we have mentioned previously in association with the setting up of the School Dental Nurse program within Finland) in Helsinki, the New Zealand High Commission in London and the Prime Minister’s Office in Wellington, New Zealand and the Australian Prime Minister’s Office in Canberra, it was agreed that an officially endorsed ANZAC Volunteer Battalion would be dispatched to assist Finland. As mentioned previously, this undertaking was largely taken based on the initiative of the New Zealander, Colonel Hunter, who as a result of his former role as Commander of the New Zealand Army Dental Corps in WW1 as well as his Civil Service role, had extensive high-level contacts within the New Zealand Government and Military and the New Zealand High Commission in London.

Colonel Hunter was almost solely responsible for the agreement of both the New Zealand and Australian governments to his initiative. At the time, both countries were actively mobilising, having as loyal members of the British Commonwealth declared war on Germany at the same time as the UK. There was therefore a marked reluctance on the part of the military in both countries to dissipate their limited strength on an obscure sideshow. When it was pointed out that, based on distance alone, for any force to be of use to the Finns it would need to come from the UK rather than the Pacific (a minimum of 8 weeks would be needed simply to ship soldiers from New Zealand and Australian to Norway) the military changed their tune. ANZAC volunteers from the UK would in no way affect the buildup of the military in New Zealand and Australia. And the loss of a few hundred ANZAC’s to the UK would be virtually meaningless in terms of overall British Army strength.

Colonel Hunter’s proposal that this Battalion would be manned from New Zealand and Australian volunteers resident in the UK (of whom there were many), preferably with men with previous military training therefore met with rapid agreement. The decision to accept Australian and New Zealand volunteers was announced in the London papers on the 6th of December 1939, and on the next day the New Zealand High Commission was deluged with volunteers, far more than were needed in point of fact, with many South Africans and Rhodesians eager to assist also queing up on the offchance that they might be selected. One of the first to be selected for the Battalion was Captain John Mulgan, New Zealand author, Rhodes Scholar and at the time an Officer in the British Army.

Captain John Mulgan, New Zealand author, Rhodes Scholar and Rifle Company Commander, ANZAC Volunteer Battalion (Finland)

Mulgan was born in Christchurch in 1911, was good at sport as well as academic work, after Auckland Grammer School he went on to Auckland University where his main subjects were English and Greek. Towards the end of 1933, he entered Merton College, Oxford, and took a first class degree in English. He then worked for the Clarendon Press, and in 1936 he began a fortnightly newspaper column, `Behind the Cables’, which was run in the (New Zealand) Auckland Star newspaper, providing an informed commentary on current European politics for New Zealand readers. In September 1939, Mulgan joined the 5th Battalion of the Oxford and Bucks (British Army) as an Officer while at the same time he also began recording a number of radio broadcasts, `Calling New Zealand’, which revealed a flair for radio journalism. In December 1939 he volunteered for the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion (Finland) and was immediately accepted, promoted to Captain and placed in command of a Rifle Company.

It was here, after seven years away from his country that he again met up with large numbers of New Zealanders. He was emotionally stirred by the meeting. “It was like coming home. They were mature men, these New Zealander Volunteers, quiet and shrewd and sceptical. They had none of the tired patience of the Englishman, nor that automatic discipline that never questions orders to see if they make sense. Everything that was good from that small, remote country had gone into them, sunshine and strength, good sense, patience, the versatility of practical men. And they marched into history.” They did indeed, and Mulgan was one of reasons that they did so, although he would himself have denied it. Mulgan continued to record radio broadcasts for the New Zealand (and Australian) public for the duration of the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion’s service in Finland. Entitled “ANZACS in Finland,” the regular radio broadcasts found a world-wide audience in the English-speaking world. After the return of the volunteers to the UK in late 1940, Mulgan returned to the British Army and in 1942 was posted to the Middle East. As second-in-command of an infantry regiment, Mulgan fought in the front line at Alamein.

After Alamein, Mulgan risked severe consequences when he challenged the competence of his commanding officer. He transferred to another British battalion, served in Iraq and then in May 1943 he joined the Special Operations Executive with Force 133. A few months later he was parachuted into Northern Greece. For the next year he ran guerrilla actions against the occupying German forces, and was also entangled in the increasingly complex slide towards Greek civil war. He was the only SOE officer to directly command Greek andartes, and was awarded the Military Cross for his strikes against German communications. Ill and exhausted, Mulgan was flown to Cairo in October 1944. He spent early 1945 in Athens, where he directed the British payment of compensation to Greek families who had assisted the Allies. He returned from Athens to Cairo in mid-April 1945, where he wound up a number of obligations, wrote his now-classic account of the ANZAC Volunteer’s in Finland, “Finnish Odyssey – the ANZAC Volunteers in Finland, 1940” (published by Whitcome and Tombs, 1947), wrote a report to the New Zealand Department of Foreign Affairs on the suitability of Greeks as immigrants, and made arrangements to transfer to the New Zealand Division. The day before that planned homecoming, on Anzac Day 1945, Mulgan took an overdose of morphine from his medical kit. The reasons for his suicide remain unexplained.

From the approximately twelve thousand volunteers, those without any military training or experience or with dependents were immediately rejected (which also got rid of the underage volunteers – the test for previous military experience was simple and straightforward. Volunteers were thrown a dirty and somewhat rusty Lee-Enfield .303 Rifle and told to strip it and clean it. Those who did so within a time limit of which they were not aware were passed. And it was obvious who had no idea how to handle a rifle). Those overage, obviously completely unfit or who failed the medical exam, were also rejected. It was decided that South Africans and Rhodesian volunteers would be accepted – rugby players and outdoorsmen, they fitted in well with the Kiwis and Aussies. The end result of the selection process, which was completed rapidly over a three day period, was a substantially over-strength Battalion of approximately 1,166 men, structured as follows.

ANZAC Volunteer Battalion (Finland Volunteers)

• Battalion Headquarters (5 Officers, 50 men)

• Headquarter Company (24 Officers, 170 men) comprised of;

Company HQ (2 Officers, 12 men)

Signals Platoon (2 Officers, 35 men)

Administration Section (1 Officers, 11 men)

Transport Platoon (2 Officers, 42 men)

Reconnaissance Platoon (2 Officers, 35 men)

Medical Platoon (5 Officers, 10 Nurses (Officers), 35 Medical Orderlies)

• Heavy Weapons Company (10 Officers, 199 men) comprised of;

Company HQ (2 Officers, 11 men)

Anti Aircraft Platoon (1 Officer, 45 men)

Mortar Platoon (2 Officers, 73 men)

Anti-tank Platoon (3 Officers, 73 men)

Assault Engineers Platoon (2 Officers, 70 men)

• Four Rifle Companies (5 Officers, 113 men), each comprised of;

Company HQ (2 Officers, 11 men)

Three Rifle Platoons, each comprised of;

Platoon HQ (1 Officer, 4 men)

Three Rifle Sections, each comprised of 10 men

• Two Reserve Rifle Companies (5 Officers, 113 men), each comprised of;

Company HQ (2 Officers, 11 men)

Three Rifle Platoons, each comprised of;

Platoon HQ (1 Officer, 4 men)

Three Rifle Sections, each comprised of 10 men

• Total Strength of 1,166 all ranks (69 Officers and 1097 men)

Incidentally, ten single female volunteers, all experienced Nurses, were accepted and immediately sworn in as Nursing Officers. With the assistance of the British Government and the British Army, who were more than bemused at the rapid and decisive pace of the New Zealanders, progress was quickly made. Each day for the next three days, volunteers were notified of their acceptance and told to report that same evening to the High Commission from where they would be transported to a training camp. From the High Commission, they were bussed to Euston Station and placed on a nightly Special to Scotland. After reaching Edinburg, they were transported northwards to Aberdeen, where an existing British Army Camp had been hastily taken over. By the 12th of December, personnel for the entire Volunteer Battalion were in camp and in the process of being equipped from British Army stores.

At the same time, a heated debate was going on within New Zealand Government circles over the command of the Volunteer Battalion. The British Government had offered to provide a senior British Officer to take command as the volunteers themselves included no senior ANZAC Officers. This proposal was anathema to both the Australian and New Zealand governments, for whom placing an ANZAC contingent under direct command of a British Officer would have been a political hot potatoe. Memories of Gallipoli and the suicidal attacks of WW1 were still strong in both countries. As the whole contingent was largely being put together under the auspices of the New Zealand Government, the Australians in this case deferred to New Zealand, who made the decision to appoint New Zealand Territorial Army Lieutenant-Colonel Howard Karl Kippenberger as the Commanding Officer. Kippenberger was born in Ladbrooks, near Christchurch, New Zealand, the son of a schoolmaster who later became a farmer at Waimate. Kippenberger received his education at Christchurch Boys’ High School and later at Canterbury University College.

Howard Kippenberger, CO, ANZAC Volunteer Battalion with Charles Upham, another Volunteer (Upham was only the third person to receive the VC twice, the only person to receive two VCs during the Second World War and the only combat soldier ever to receive the award twice)

After the eventual withdrawal of the survivors of the ANZAC Volunteers from Finland, Kippenberger was perhaps the single most experienced senior Officer in the New Zealand Army. He was transferred to the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in the Middle East almost immediately and commanded a composite Brigade in Greece, where he distinguished himself in his conduct of a fighting withdrawal. He then commanded a further composite Brigade in Crete where he again distinguished himself in the ill-fated defence of Crete. In the fierce fighting at Bel Hamed, in late November 1941, he was wounded and taken prisoner. He organised an escape for himself and 20 others and, after a sojourn in hospital, was promoted to Brigadier, commanding the New Zealand 5th Infantry Brigade. He took the brigade back to the Western Desert to build the El Adem box before moving east to join the rest of the NZ Division in Syria. Then followed the fighting and breakout at Minqar Qaim, the battles of El Mreir and Ruweisat Ridge, the holding of the line, and in October-November the turning of the tide at El Alamein, in all of which Kippenberger played a prominent part and during which he was awarded his first D.S.O. During the fighting across North Africa to Takrouna in Tunisia, Brigadier Kippenberger continuously led the 5th Brigade in operations apart from the occasions when, in General Freyberg’s absence at Corps Headquarters, he was acting Major-General in command of the Division. In that year he won a bar to his D.S.O.

After a short furlough he resumed command of the 5th Brigade at the Sangro in Italy and in February 1944 again took command of the Division as it faced up to Cassino. On 2 March, while descending Monte Trocchio, Major-General Kippenberger stepped on a mine and had one foot blown off and the other so badly shattered that it was later amputated. After convalescence in England, he took control of the repatriation of New Zealand prisoners of war released from Germany. In 1946 he returned to New Zealand to become editor-in-chief of the New Zealand War Histories, which he was determined should fittingly record New Zealand’s national effort in the Second World War. His own autobiographical account of his war “Infantry Brigadier,” appeared in 1949 and was acclaimed a classic in its field, while his account of the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion in Finland, “Forgotten Battalion: ANZAC’s in the Russo-Finnish Winter War,” appeared in 1952 to further acclaim.

In 1915, during World War I, the then 18 year old Kippenberger had enlisted as a private in the 1st Canterbury Regiment. He took part in four attacks as a Private and then as an NCO during the Battle of the Somme in the autumn of 1916. The Army repatriated him after he received a serious wound in the right arm. After the War, Kippenberger qualified as a solicitor in 1920 and later became manager and then a partner of the Rangiora branch of a Christchurch legal firm. But the Army was his great love: interested in military history and theory from a young age, he built up what was probably the most comprehensive library of military history and textbooks in New Zealand and he joined the New Zealand Territorial Army. Commissioned, he commanded the Rangiora platoon of the 1st Battalion, Canterbury Regiment. In 1929 he was promoted to Captain, in 1934 to Major, and in 1936 to Lieutenant-Colonel commanding the 1st Cants. On the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 he was appointed to command the 20th Battalion, New Zealand Division which was in the process of being hastily assembled and trained in New Zealand as part of the intended New Zealand Expeditionary Force.

Lieutenant-Colonel Howard Karl Kippenberger (28 January 1897 – 5 May 1957), known universally to everyone both above and under his command as “Kip,” agreed to his governments request, was immediately promoted to full Colonel and together with a small and hand-picked staff (which included Sgt. Charles Upham, a fellow Cantabrian) embarked on a rapid journey to the UK via trans-Tasman ship to Sydney (a 3 day trip) and thence by Imperial Airways flying boat service from Sydney to Singapore on G-ADVD Challenger (which flew the Singapore-Sydney-Singapore sector).

In Singapore, Kippenberger and his staff transferred to the Imperial Airways flying boat G-AEUB Camilla for the remainder of the trip to London.

At a time when it took six to eight weeks by ship for the same trip, it was an extremely rapid journey, with Kippenberger arriving in London on the 21st of December 1939. He spent the next two days in meetings in London with the New Zealand and Australian High Commissions and with the British Army, following which he traveled by overnight train to Aberdeen to join the Battalion as it embarked with its equipment on the Admiralty-requisitioned Polish passenger ship MS Batory. Embarkation was completed on Christmas Day and on the 26th of December 1939, the MS Batory steamed for Narvik, escorted by two Royal Navy Destroyers.

MS Batory: The M/S Batory was a large (14,287 BRT) ocean liner of the Polish merchant fleet powered by 2 sets of Wartsila marine-diesel engines driving 2 screws giving her a speed of 18 knots.

MS Batory had been built at the Crichton-Vulcan Shipyard in Turku, Finland, under an arrangement whereby part of her payment was made in shipments of coal from Poland and was launched on 8 July 1935. She was among the best-known Polish ships of the time. On the outbreak of World War 2, she had been reflagged as a Finnish ship under the terms of the secret Finnish-Polish defence agreement and had for the duration of World War II, she served as a troop transport and a hospital ship. In June /July, 1940 she secretly transported much of Britain’s gold reserves (₤40 million) from Greenock, Scotland to Montreal, Canada for safekeeping. In August to September of that year, she transported 700 British children to Australia for safekeeping. In the same year she, along with the Polish ship M/S Chrobry, she transported allied troops to Norway following the German invasion.

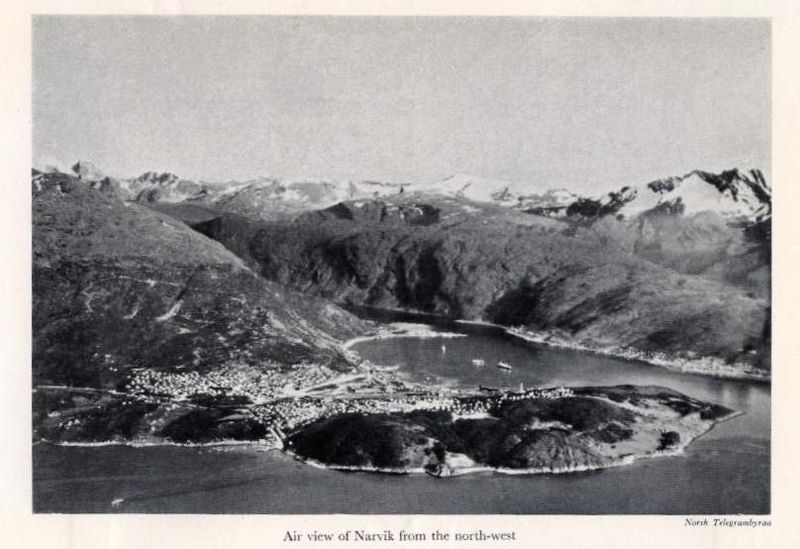

The voyage to Narvik was rapid, with the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion disembarking from the Batory on December 30th after a frantic two days of unloading stores and military equipment. Narvik itself was somewhat in a state on confusion, if not downright chaos at the time, with Finnish-flagged ships arriving one after the other. Many of them carried shipments of military cargo which had been en-route to Finland but with the outbreak of war, they had been diverted to Narvik. The two ex-Italian Finnish Navy Cruisers, Ilmarinen and Vainamoinen were also in port and very much on guard against the possibility of a Soviet attack on what was turning into a major logistical chokepoint. The local Norwegian authorities were in a state of complete confusion, with no idea whatsoever as to what they were supposed to do and with no instructions from Oslo. That said, they were keen to assist the Finns but with no real idea as to what to do or how to address the shiploads of military stores and equipment arriving. The Norwegians were even more confused by the Battalion of ANZAC troops which suddenly disembarked in their midst. Nobody had forewarned them and for a while, it seemed that they thought they were being invaded, although outright combat was fortunately averted.

Even the elderly Finnish liasion officers in Narvik had no idea the ANZAC’s were coming and while the Swedes were allowing Finnish military supplies to be freighted through Sweden on the rail line, they flat out forebade troop movements, especially troops armed to the teeth and looking for a fight, and the Finnish liasion officers had no other means of moving the ANZAC troops through to Finland short of marching on their own feet. Kippenberger however, was not a man to sit and wait for a solution to present itself, and not for nothing over the course of the Winter War did his Battalion’s ability to help itself to enemy—and allied—heavy weapons and transport lead to it being nicknamed “Kip’s Thousand Thieves.” Kippenberger simply gathered his officers and NCO’s together and told them to go out and find a solution.

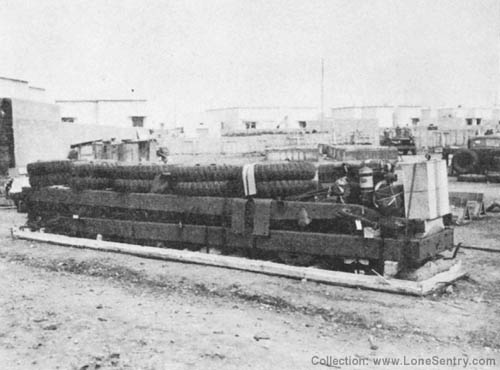

Within two days, he had one. One of his NCO’s came back to report that two of the Finnish cargo ships anchored in the sound awaiting unloading were filled with a massive shipment of GMC 2.5 Ton Trucks which the Finnish Army had purchased. Not even the Finnish liasion officers were aware of the cargo. “Kip” moved into action. As the MS Batory pulled away from the docks, the ANZAC’s moved in and took over control of the dock space while one of the Cargo Ships was moved up. The Norwegians went ballistic, the Finns expressed concern, the Kiwis shrugged and the Aussies simply said “Fuck Off Mate” and hefted the Norwegian beer bottles they had seemed to acquire from thin air. Within hours, GMC Trucks were being rapidly assembled on the spot as fast as the ANZAC’s could get them out of the ships holds and onto the dock.

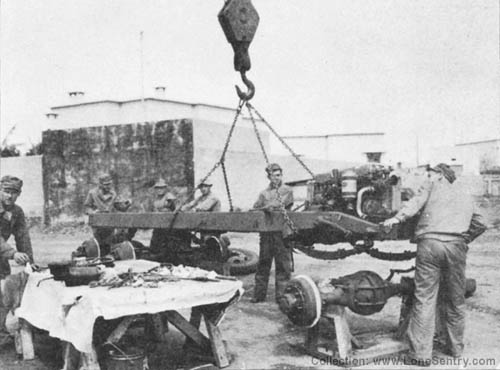

However, Kippenberger went slightly further than simply meeting his own transportation needs. Most of his men came from rural farming backgrounds, and both New Zealand and Australia by the late 1930’s had extensively mechanised agriculture. The men were handy with machinery and many of them knew trucks and tractors intimately. The ANZAC’s offloaded and assembled the entire two shipments of trucks, some five hundred trucks in total, over the course of a week, included around fifty smaller Chevrolet trucks. With the assistance of the Norwegian townsfolk whom Kip cajoled (not that the Norwegians needed much cajoling) into volunteering their labour, all five hundred GMC trucks were loaded to capacity with urgently needed military supplies. The MS Batory had also carried a shipment of 60 British 18 pdr Field Gun’s, the Mk II – these, along with 240,000 rounds of ammunition for the guns, had been purchased by the New Zealand and Australian governments from Britain and donated to Finland. The guns were the model 1918 with pneumatic tires and had been all equipped for motorised towing (which is how they were towed in Finland). With a range of 6.5-10.7 kms and capable of firing ten to twelve 8.16-8.40 kg HE rounds per minute, they were an effective artillery piece. Kip had the sixty guns hooked on to the backs of his trucks and had a good part of the ammunition loaded – which, along with petrol in drums and jerricans, accounted for the loading of almost all the trucks.

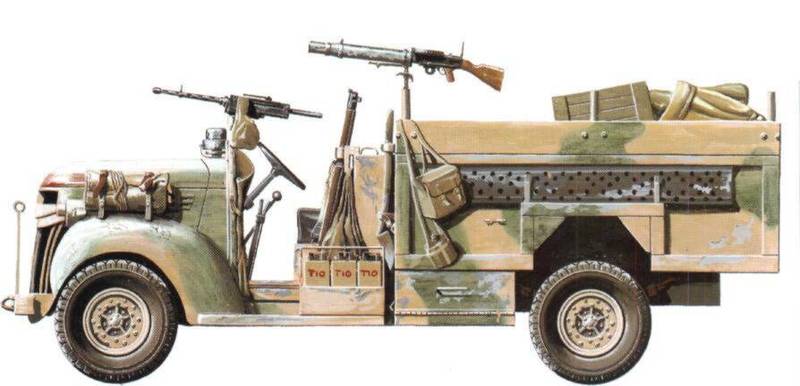

Neither the Finns nor the Norwegians knew quite what to make of the energetic and forceful Kiwis and Aussies as they worked day and night. And when they weren’t working, they were busy doing their best to eliminate all the beer in Narvik. And when they weren’t doing that (or sometimes at the same time), a large group was busy modifying the fifty odd Chevrolet Trucks and fitting “acquired” machine-guns to give the column an air defence capability of sorts. Places on these trucks were eagerly sought, despite the exposure to the cold as a result of little mods like the cabs being cut off.

The British Ordnance QF 18 Pounder: This gun was the standard British Army field gun of the World War I era and formed the backbone of the Royal Field Artillery during the war. It was produced in large numbers and calibre (84 mm) and hence shell weight were greater than those of the equivalent field guns in French (75 mm) and German (77 mm) service. It was generally horse drawn until mechanisation in the 1930s. The first versions were introduced in 1904 and later versions remained in service with British forces until early 1942. This is the updated version with pneumatic tires and equipped for motorised towing as supplied to Finland.

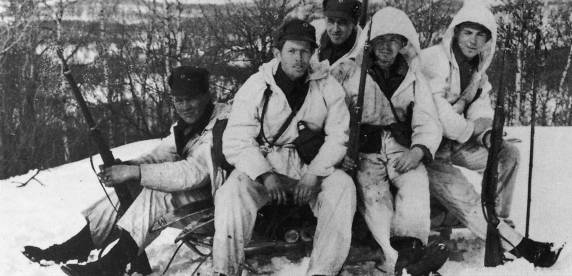

A week to the day after they had arrived in Narvik the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion set out by road. The Battalion had augmented its strength somewhat with most of the men from a Norwegian Reserve Artillery unit who volunteered en-masse to man the 18 Pdr Guns, as well as enough additional Norwegian volunteers to form up a further two Rifle Companies (the Norwegians also supplied skis and winter clothing and camoflauge to the ANZAC soldiers, although their ability to use the skiis provided was highly doubtful). Now with its own Artillery “Regiment” of 60 guns, and with a strength of eight Rifle Companies, the Battalion was more of a Light Brigade.

Occassionally, the snow was a little more than the ANZAC’s were used too…..but they still got through……

Driving in heavy snow was not a new experience to many of the Kiwi soldiers from the South Island of New Zealand and, assisted by snow-plough attachments thoughtfully provided by the Norwegians and jury-rigged onto the trucks by the Kiwis they made good progress as they headed north from Narvik, utilizing every hour of daylight. They hit the intersection with the new all-weather Finnish road to the Norwegian port of Lyngefjord (which the Finns were busily building up as an alternative port to Narvik and Petsamo) and from there they drove east and south, reaching Rovaniemi less than a week after they had departed Narvik. News of their arrival had not preceded them in any detail, and the seemingly endless stream of heavily laden American trucks, many towing artillery and flying their collection of New Zealand, Australian, South African, Rhodesian and Norwegian flags and emblems that drove through Rovaniemi and continued southwards brought out what passed for crowds in Rovaniemi to watch and wave and cheer as the ANZAC’s passed through. Interspersed with the GMC 2.5T trucks were the smaller Chevrolet Trucks that the ANZAC’s had modified in Narvik for air defence, fitting them with machineguns purloined from every source available.

The Battalion arrived in Oulu a day later. By now the Finns were well and truly aware of what was coming down the road and there was a welcome of sorts awaiting them. At a checkpoint outside Oulu the column was redirected to an Army Camp and the soldiers, exhausted from a week on continuous road-clearing and driving, were fed and directed to barracks to sleep. It was the first experience the ANZAC troopies had with the women of the Lotta Svard organisation, and in general, despite their exhaustion, they were suitably impressed. A few had enough energy to try their usual pickup lines, but sadly, they knew little or no Finnish and the Lotta Svard girls and women professed not to understand the Australasian version of English. From the laughter and giggles and the occassional whack to the side of an Aussie or Kiwi head, perhaps they understood more than they let on! Meanwhile, “Kip” and his staff were meeting with the somewhat puzzled Finnish Officers running the skeleton military organisation in Oulu, who were in their turn on the phone to Military Headquarters asking what to do with the rather piratical-looking bunch of Volunteers who had arrived armed to the teeth and asking where they could go to find a decent scrap.

ANZACS on the move: Men of the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion rolling through a village as they withdraw from Eastern Karelia, Late Summer 1940. Still in possession of some of the GMC2.5T Trucks (and still with the old American markings) they had “acquired” in Narvik. They lost half their number dead in battle, but they were never defeated.

The story of the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion over the course of the Winter War is told elsewhere. Suffice it to say that they fought well, at first independently and then as part of the Commonwealth Division. In late summer 1940, after the signing of the Peace Treaty between Finland and the USSR, the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion was withdrawn from the front and transported to Helsinki. For all that they’d been in Finland for the best part of 9 months, none of them had been on leave and apart from what they’d seen during their arrival, all they had seen of Finland were the forests, lakes and swamps of Eastern Karelia. “And lots of Russians,” as they often responded when asked later. “Lots and lots of Russians, the bastards were worse than bluebottles, swat down one and there were always more of the buggers.” Arriving in Helsinki, they were given one weeks leave while arrangements were made to return them to the UK via the port at Lyngenfjord, which was now the main access route to Finland.

Before they departed, a formal memorial parade and Dawn Service took place, beginning as the sun’s first rays lightened the darkness. The Service started with a reading and then the singing of the traditional New Zealand Maori farewell song, Po Atarau.

(Not from the right period unfortunately – this is a bunch of NZ Army guys in Bosnia in 1995, but you get the flavor. Imagine a few hundred soldiers singing like this – pretty moving stuff for any Kiwi).

Pö atarau

E moea iho nei

E haere ana

Koe ki pämamao

Haere rä

Ka hoki mai anö

Ki i te tau

E tangi atu nei

(On a moonlit night

I see in a dream

You going

To a distant land

Farewell,

But return again

To your loved one,

Weeping here)

A wreath was then laid at the base of the memorial and the traditional Anzac Dedication was read.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

We will remember them.

A lone bugler then played the Last Post, there was a minute’s silence and then Reveille completed the formal and solemn occasion.

(The ANZAC Ode comes from “For the Fallen”, a poem by the English poet and writer Laurence Binyon and was published in London in The Winnowing Fan: Poems of the Great War in 1914. This verse, which became the ANZAC Ode, has been used in association with commemoration services in Australia and New Zealand since 1921. Perhaps an even more fitting memorial is two songs, one from New Zealand, the other from Australia)

Following the signing of the peace treaty between Finland and the USSR in late 1940, and the withdrawal of the Germans from Norway in the same timeframe, the now sadly reduced ANZAC Volunteer Battalion travelled from Helsinki to Lyngefjord by train and truck and their embarked on the short voyage to the UK. From there most of them eventually continued on to the Middle East to rejoin their compatriots in the New Zealand, Australian, South African and Rhodesian forces in the battles that culminated in the final Victory over Germany.

Can you hear Australia’s heroes marching?

Can you hear them as they march into eternity?

There will never be a greater love

There just couldn’t be a greater sacrifice

There just couldn’t be

Can you hear Australia’s heroes marching?

The ones who fought and gave their all

Can you hear Australia’s heroes marching?

Can you hear them as they march into eternity?

There will never be a greater love

There just couldn’t be a greater sacrifice

There just couldn’t be

Can you hear Australia’s heroes marching?

They’re marching once again

Across our great land

Can you hear Australia’s heroes marching?

Can you hear them as they march into eternity?

There will never be a greater love

There just couldn’t be a greater sacrifice

There just couldn’t be

Can you hear Australia’s heroes marching?

And there, in October 1940, we shall leave the gallant remnants of the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion (Finland). Their dead rest in peace in the Cemetry in Eastern Karelia near where they fell. Their memory lives on in the Cenotaph that stands over them deep in the Eastern Karelian forests.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

2 Responses to First Volunteers – The ANZAC Volunteer Battalion arrives in Finland