As the 1938 Ilmavoimat and Merivoimat Air Arm Procurement Program kicked off in the New Year, VL already had a number of projects underway. These are summarised here, before we move on to the details of the 1938 Ilmavoimat and Merivoimat orders.

The VL Viima Manufacturing Program

As you may recall, the Ministry of Defense had ordered 60 Viima IIs on 27 June, 1936. These were delivered starting from December 1936, with the final aircraft completed and delivered in July 1938. The Viima production line was then converted over to the production of the VL Pyry Advanced Trainers which were ordered in early 1938 (detailed below).

The VL Fokker D.XXI Manufacturing Program

An initial order that had been placed with VL for 20 Fokker D.XXI fighters (in addition to the 20 purchased outright from Fokker) was increased by another 20 in mid-1936. VL went on to build and deliver forty Fokker D.XXI’s over the period late-1936 to early 1938, with one per week rolling of the construction line by mid-1937 (by which time, 60 Fokker D.XXI’s were in service, equipping three fighter squadrons). Production ceased in early 1938 and the Fokker production line was converted over to the newly ordered Miles M.20 Fighter (detailed below).

The VL Bristol Blenheim Manufacturing Program

By the end of 1937, 22 VL-built Blenheim’s had been completed. Construction continued with a further 20 completed up to October 1938, bringing the total delivered by VL to the Ilmavoimat to some 42, in addition to the 20 that had been delivered from Britain. With 62 Bristol Blenheim’s in service, production of Bristol Blenheims by VL was discontinued in October 1938 in order to concentrate on conversion of the production line over to the new VL Wihuri fighter-bomber.

The VL Wihuri Manufacturing Program

Even with the assistance of De Havilland, significant issues were experienced getting the VL Wihuri program underway. A following Post will go into this project, the difficulties and challenges experienced and how they were overcome.

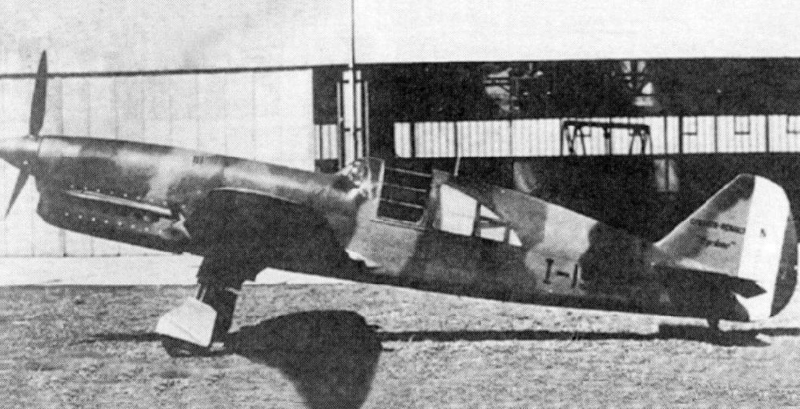

VL Pyry Advanced Trainer – 40 ordered in early 1938

In 1936 it had been decided that in light of the rapid advances in aircraft technology and designs and the decision to purchase monoplane fighter aircraft for the first time, a newer monoplane Advanced Trainer was needed. In 1936 the Ilmavoimat had commissioned a design and a prototype from the State Aircraft Factory (VL) and in mid 1937 a prototype for the new advanced fighter trainer, the VL Pyry, was delivered. The first flight of the Pyry prototype was on 29 August 1937. The test program was completed by November 1937, with the aircraft proving to meet all the requirements.

The Ilmavoimat ordered a first series of 40 aircraft on 3 May 1938 and in August 1938, work began to convert the Viima production line over to produce the Pyry. Preparations had been underway since the order had been placed and the conversion was swift. Construction of the first Pyry started in October 1938 and the 40 aircraft ordered were delivered between December 1938 and June 1939.

The VL Pyry remained in use as an Advanced Trainer for the Ilmavoimat until 1962.

Miles M.20 Fighter – ordered June 1938

While the De Havilland-designed VL Wihuri bomber project that was underway from 1937 replaced the Blenheim construction program in late 1938, the Ilmavoimat was searching for a more modern fighter aircraft that VL could build as Fokker D.XXI production ended. With the rearmament programs of all the major european powers underway, sourcing fighter aircraft from suppliers in these countries (and the leading european fighters were all either German, French, British or Italian) was now increasingly problematical and the implementation of more modern aircraft construction technology was also a challenge. Thus, VL looked in two directions at once. The first was for a fighter that could be be constructed in Finland using as close to existing methods as possible in order to reduce the lead time, would be relatively cheap and would have performance on a par or superior to the Hawker Hurricanes or Curtiss Hawks. The second was to acquire the industrial machinery and expertise to allow VL to move to more modern construction methods and to license a modern fighter to build locally.

The de Havilland Wihuri project was proving that the first was possible, but the Wihuri project was behind schedule. Something that could enter service in a shorter timeframe – and that would be a pure fighter – was desired. The 1938 Ilmavoimat Procurement Team spent the first few months of 1938 exploring options with different aircraft manufacturers – and narrowed the options down to two by early May. The French in particular were already working on designs to meet a 1936 specification for “light fighter” of wooden construction that could be built rapidly in large numbers. Three design projects were underway in mid-1937, the Arsenal VG-30, the Caudron C.714 and the Bloch MB-700.

The French “Light Fighter” Designs

The Arsenal VG-30 was a conventional, a low-wing monoplane that was all wooden in construction, using plywood over stringers in a semi-monocoque construction and which was to be powered by the Potez 12Dc flat-12 air-cooled inline engine, (which was running into development problems). The VG-30 was to be armed with a 20 mm Hispano-Suiza HS.404 cannon firing through the propeller hub, and four 7.5 mm MAC 1934 M39 drum-fed machine guns, two in each wing. The VG-33 was intended to match theMe109 in in speed (347mph) and maneuverability and the prototype was scheduled to fly in October 1938.

The VG-33 was a modified version of the VG-31 using the Hispano-Suiza 12Y-31 engine, and first flew on April 25, 1939. It had a surprisingly good performance of 347mph, and was ordered into production with a contract for 220 aircraft in September 1939, later raised to 1,000. Production didn’t take long to start, but most of the airframes never received engines and were sitting at the factory when it fell to the Germans.

In larger quantities, this plane could have shown the Luftwaffe a rough time, but as was the case for most French planes, production problems plagued the VG-33 such that only 160 aircraft were close to completion before the Armistice, with just 19 of 40 produced actually taken on by the Armée de l’Air. Just two machines flew in an active group, the piecemeal GC 1/55 which began life on June 18 1940 and conducted missions for just one week.

In early 1938, the Arsenal VG-30 was still in the design stages and a prototype was not available for evaluation. The 1938 Ilmavoimat Procurement Team looked at the designs but given the experience with the Loire-Nieuport LN-419 Dive-Bomber, decided to wait until a prototype was completed and flying before a further evaluation. In the event, a prototype was available in May 1939, and the Ilmavoimat did look further at this aircraft but again, would decide against any follow-up.

The Caudron C.714 was based on the C.710 model, which was an angular design developed from an earlier series of air racers. One common feature of the Caudron line was an extremely long nose that set the cockpit far back on the fuselage.

The profile was the result of using the 336 kW (450 hp) Renault 12R-01 12-cylinder inline engine, which had a small cross section and was fairly easy to streamline, but very long. The landing gear was fixed and spatted, and the vertical stabilizer was a seemingly World War I-era semicircle instead of a more common trapezoidal or triangular design. Armament consisted of a 20 mm Hispano-Suiza HS.9 cannon under each wing in a small pod.

The C.710 prototype first flew on 18 July 1936. Despite its small size, it showed good potential and was able to reach a level speed of 470 km/h (292 mph) during flight testing. Further development continued with the C.711 and C.712 with more powerful engines, while the C.713 which flew on 15 December 1937 introduced retractable landing gear and a more conventional triangular vertical stabilizer. The final evolution of the 710 series was the C.714 Cyclone, a variation on the C.713 which first flew in April 1938 as the C.714.01 prototype. The primary changes were a new wing airfoil profile, a strengthened fuselage, and instead of two cannons, the fighter had four 7.5 mm MAC 1934 machine guns in the wing gondolas. It was powered by the newer 12R-03 version of the engine, which introduced a new carburetor that could operate in negative g. The Armée de l’Air ordered 20 C.714s on 5 November 1938, with options for a further 180. Production started at a Renault factory in the Paris suburbs in summer 1939.

The 1938 Ilmavoimat Procurement Team conducted an evaluation and completed a series of test flights with the prototype C.714 Cyclone in June 1938, but considered the climb rate poor and the aircrafts maneuverability to be well below par. A decision was made at this stage to eliminate this design from consideration..

In France, deliveries to the Armée de l’Air did not start until January 1940. After a series of tests with the first production examples, it became apparent that the design was seriously flawed. Although light and fast, its wooden construction did not permit a more powerful engine to be fitted. The original engine seriously limited its climb rate and maneuverability with the result that the Caudron was withdrawn from active service in February 1940. In March, the initial production order was reduced to 90, as the performance was not considered good enough to warrant further production contracts. On 18 May 1940, 35 Caudrons were delivered to the Polish Warsaw Squadron, the Groupe de Chasse polonais I/145, stationed at the Mions airfield. After just 23 sorties, adverse opinion of the fighter was confirmed by front line pilots who expressed concerns that it was seriously underpowered and was no match for contemporary German fighters.

On 25 May 1940, only a week after it was introduced, French Minister of War Guy la Chambre ordered all C.714s to be withdrawn from active service. While the Ilmavoimat did not order any Caudron C.714’s, a number ended up with the Ilmavoimat. Eighty were diverted by the French Government to Finland to fight in the Winter War. These were meant to be flown by French pilots but with the war in France going badly, the French instead released the Polish pilots who were already flying Caudron C.714’s, the Warsaw Squadron of the Groupe de Chasse Polonais I/145, from the fighting and dispatched them to Finland. The Poles flew their remaining 30 Caudron’s to Britain and then to Sweden before continuing to Norway. There, they flew the Caudron’s through the remainder of the Winter War, losing nine in combat and nine in accidents on landing and takeoff.

Of the fifty additional C.714’s that were to be shipped to Finland, events in France resulted in only six aircraft being delivered, and an additional 10 were waiting in the harbor when deliveries were stopped. The six aircraft that arrived were assembled, tested and given registrations CA-551 to CA-556. Finnish pilots found the aircraft were too unreliable and dangerous to use in Finnish conditions, but after the Polish pilots firmly stated that they were prepared to fly any fighter aircraft available, however dangerous, they were released to the Polish Squadron as replacements. Two of the aircraft were damaged during a transport flight to Pori. Further, the Finnish pilots found that it was difficult to start and land the aircraft from the air bases at the front. Following the end of the Winter War, the surviving Finnish CR.714 aircraft were permanently grounded on 10 September 1940, and taken out of service in 1941.

The Bloch MB-700: As mentioned above, in the last few years before the war, the French Air Ministry began to consider using non-strategic materials such as tropical woods for warplane construction to avoid running short of steel or light alloys in the event of a conflict. On 12 January 1937, the Ministry’s STAé Aeronautical Department issued technical specification A23, calling for light C1 single-seat fighters of wooden construction using less-powerful engines than the 900/1,000hp units in the basic fighter programme. To meet this requirement, André Herbemont, who had designed all the SPAD fighters since 1918, produced the MB 700.

It was designed and built in the former Blériot Aéronautique factories in Suresnes, which had been incorporated into SNCASO when the French aviation industry was nationalised in 1936. The MB 700 featured an all-wood, stressed-skin structure; the fuselage was covered with formed plywood in the forward section, canvas in the rear. The engine was a Gnome-Rhône 14 M6 delivering 700hp at takeoff. As designed, the MB-700 was to be equipped with two Hispano Suiza HS 404 cannons and two wing-mounted MAC 1934 M 39 machine guns or four wing-mounted 7.5mm M 39 machine guns

In early 1938, the Bloch MB-700 was still in the design stages and a prototype was not available for evaluation. The Ilmavoimat Procurement Team looked at the designs but as with the Arsenal VG, given the experience with the Loire-Nieuport LN-419 Dive-Bomber, decided to wait until a prototype was completed and flying before a further evaluation. In the event, a prototype was not available until April 1940, and the Ilmavoimat did not look further at this aircraft.

The MB 700-01 made its first flight on 19 April 1940, with Daniel Rastel at the controls. It lasted 16 minutes and reached an altitude of 1,800 metres. The second flight was not completed until 13 May 1940, again with Daniel Rastel. During this 50 minute flight, the aircraft reached 4,000 metres. The prototype had not been fitted with weapons. It reached a speed of 550km/h (342mph) and had a range of 685 miles, which was a remarkable performance considering the available power. The prototype had only completed about 10 flying hours when the Buc airfield was occupied by German forces who burned the plane. Construction of a second prototype was started but never finished. It featured a number of modifications in relation to the 01: larger propeller, modified radiator, etc. A naval version, baptised MB 720, was also designed, but never got off the drawing board.

Falling back on the British – the Miles M.20 Fighter

With work on the de Havilland Wihuri well underway in early 1938, the Ilmavoimat Procurement Team approached de Havilland for ideas. Geoffrey de Havilland in turn referred them to Frederick George Miles, the designer of the recently purchased Miles Kestrel Trainer. Miles was an outstanding aircraft designer and the aircraft he came up with were often technologically and aerodynamically advanced for their time. Peripherally aware of Miles’ growing reputation but largely influenced by de Havilland’s recommendation, the Ilmavoimat approached him in July 1938 and asked for ideas for a fighter aircraft that could be constructed in Finland cheaply and with regard to Finland’s resource and strategic limitations. Miles came up with an initial design within two weeks and the Ilmavoimat promptly commissioned a prototype. To reduce production times the aircraft was to be as close as possible to all-wood construction and would use as many parts as possible from the Fokker D.XXI construction program,. The engine was to be the Finnish produced Hispano-Suiza.

The first prototype flew 65 days after the commission was placed, in late October 1938. Almost all wood, it lacked hydraulics, and had streamlined fixed spatted landing gear and was powered by a Finnish-manufactured Hispano-Suiza engine. The prototype also featured a bubble canopy for improved pilot visibility, one of the first fighters to do so and a feature that the Ilmavoimat would on to include in (and retrofit to) their fighter aircraft wherever possible. The prototype was armed with eight wing-mounted machineguns and was actually faster than the Hawker Hurricane (but slower than the Spitfire) – and could carry more ammunition than either. With a maximum speed of 333 mph, a service ceiling of 32,800 feet and and a range of 920 miles, it was the fighter the Ilmavoimat had been looking for.

The Ilmavoimat conducted test flights through November and December 1938 and after the conclusion of these, ordered an initial batch of 20 from Miles Aircraft (these were built by Philips and Powis Aircraft at Woodley airfield in Reading and delivered in May 1939), purchased an unlimited license to manufacture the aircraft and with the assistance of engineers from Philips and Powis converted the Fokker D.XXI production line at VL (the State Aircraft Factory) over to construction of the new fighter aircraft over January-March 1939. Initial production was slow, the first 2 Finnish prototypes were only completed in May 1939, but thereafter some 4 aircraft a month were completed through to November 1939 (26 Miles M.20 fighters had been delivered by VL by the end of November 1939 – 46 were in service at the start of the Winter War). VL construction continued throughout the Winter War, with an average of 6 aircraft per month being completed from January 1940 on as production was stepped up.

In addition, in late August 1939, the secret addenda within the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact concerning Poland, Finland and the Baltic States became known to Finland through both Germany and the USA. Under the circumstances, money became no object and the emphasis was placed on the urgent acquisition of more arms, munitions and aircraft – and an urgent order for a further 60 Miles M.20 Fighters was placed with Philips and Powis Aircraft immediately. Construction was rapid as the order specified that the Finns would supply their own engines and armament, thus bypassing the bottleneck that existed in Britain, where any war-related manufacturing was dedicated to meeting the surging demands of the UK military. A first shipment of 25 of the aircraft was received in late December 1939 via Lyngefjiord, these were transported to Tampere where engines and machineguns were fitted and they entered service in late March 1940, replacing losses and allowing (together with VL-manufactured aircraft) for a third squadron to be equipped with the Miles M.20 fighters. The remaining aircraft were not delivered as the UK cancelled the order and moved Philips and Powis Aircraft over to construction of Miles Magister target tugs and Miles Master trainers for the RAF. Finland protested that the aircraft were desperately needed, but to no avail. For the British government, British needs came first and foremost.

In service with the Ilmavoimat, the Miles M.20 proved to be a fast, strong and highly maneuverable aircraft, highly effective in combat and cheap and fast to build, albeit without any armor for the pilots. Pilots loved the visibility afforded by the bubble canopy as well as the fire power, speed and maneuverability which made the fighter an excellent dog-fighter, able to easily mix it with the agile and maneuverable Soviet fighters. Construction was straightforward and after war broke out, VL managed to step up production to 6 aircraft per month in January 1940. By May 1940, VL through superhuman efforts had raised output to some 10 per month, whereupon the limitation became the production of aircraft engines. The Finnish Government had earlier set up the State Aircraft Engine Factory, which in 1938 had begun producing the Hispano-Suiza engines under license as well as the Bristol Mercury, also under license. By mid-1939, with the threat of war with the Soviet Union looming ever larger, engine production was stepped up with work running 24/7 around the clock and output doubling over the period July-October 1939. With Finnish construction of the de Havilland Wihuris (each of which required two Hispano-Suiza’s) as well as the Miles M.20 Fighters and the Fokker G1’s, engine manufacturing became, if not quite a bottleneck, at least very tight as replacement engines were also needed for aircraft already in service.

OTL Note: During the Battle of Britain, the Royal Air Force was faced with a potential shortage of fighters. To meet the Luftwaffe threat, the Air Ministry commissioned Miles Aircraft to design the M.20. Designed and built as a simple and cheap alternative to the Spitfire and Hurricane, the first prototype flew 65 days after the design was commissioned (15 September 1940) and tested out in compliance with Specification F.19/40., the engine used was the Rolls Royce Merlin, identical to those used on the Avro Lancaster and some Bristol Beaufighter marks. Armed with the same eight .303 Browning machine guns as the RAF’s Hawker Hurricane, the M.20 prototype was actually faster than the Hurricane but slower than the Spitfire types then in production, while carrying more ammunition, and with a greater range than either. As the Luftwaffe was defeated over Britain, the need for the M.20 Fighter vanished and the design was abandoned without entering production. The first prototype was later scrapped at Woodley.

Hawker Henley Ground Attack Aircraft – 20 ordered January 1938

As mentioned for the 1937 Procurement Program, the Hawker Henley had been designed as a light bomber in response to British Air Ministry Specification P.4/34 of February 1934 for a light bomber and close support aircraft, with high performance and a low bomb load. Fairey, Gloster and Hawker all rushed to complete a design that met this need, with intense competition to achieve the highest possible performance. Hawker’s entry, the Henley, was in design and appearance closely related to the Hawker Hurricane. This was a result of the aircraft being required to carry only a modest bomb load and with performance being paramount. As the Hurricane itself was then in an advanced design stage, the Hawker design team chose to focus its efforts on developing an aircraft similar in size to the Hurricane fighter, especially as it was beneficial both economically and production-wise if assemblies were common to both aircraft.

This resulted in the Henley, as it was to become known, sharing identical outer wing panel and tailplane jigs with the Hurricane. Both were also equipped with the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine as it offered the best power/weight ratio as well as a minimal frontal area.The main difference between the two types was the cockpit, designed to carry a two man crew – pilot and observer/ air gunner. The Henley’s cantilever fabric-covered monoplane wing was mid-set, retractable tailwheel type landing gear was selected. It was also fully stressed for dive bombing and very similar in appearance to the Hurricane and able to carry 4 x 500lb bombs on underwing racks. The main difference between the two types was the cockpit, with the Henley designed to carry a two man crew – pilot and observer/ air gunner.

Although construction of a Henley prototype began as early as mid-1935, with all priorities going to Hurricane development, work on the Henley progressed slowly. The prototype took two years to complete, finally taking to the air on 10 March 1937, shortly after the competing Fairey P.4/34. Subsequently the aircraft was refitted with light alloy stressed-skin wings and a Merlin I engine, and further test flights confirmed the excellence of its overall performance. The Ilmavoimat/Meroivoimat Procurement Team evaluated and test flew the aircraft in mid-1937 – and had considered it outstanding, placing it first in the overall rankings of the aircraft they evaluated – although for financial reasons, the Vindicator was selected. In January 1938, with a large increase in budget for the 1938 financial year, the Ilmavoimat revisited the Henley and placed an immediate order for 20 with a number of modifications. In early 1938 Hawker had still not received the RAF / Air Ministry order and work to meet the Ilmavoimat order commenced immediately, particularly as the Finnish order specified that they would fit their own engines and propellers (thus avoiding the bottlenecks that were occurring in the UK with Merlin and Totol production.

The most significant modifications made by the Ilmavoimat were the elimination of the Gunner / Observer and all associated equipment together with a return to a Hurricane-like single seater cockpit /canopy, saving a considerable amount of weight – which was promptly restored by the addition of some 350 lb (159 kg) of armour plating added to the radiator housing, cockpit and fuel tanks (the Ilmavoimat had not forgotten their Junkers J1 with its “steel bathtub.” The second major modification was the fitting of two VL / Tampere / Hispano Suiza designed pods containing a British Vickers “S” 40mm cannon with 12 rounds each under each wing, together with a single machinegun in each wing loaded with tracers for aiming purposes.

The Ilmavoimat had been working on a “tank buster” project since early 1937 in an effort to come up with an effective air-based counter to Soviet armor. The 20mm Hispano-Suiza cannons had been trialled and found to be ineffective on anything except motor vehicles and light armour. The next stage had been to look at heavier guns that could be mounted in an aircraft. The Bofors 37mm had been experimented with but an auto-feeder had proved difficult to design and develop – and in looking for an alternative solution that was more ready-made, Suomen Hispano-Suiza Oy had tracked down the Vickers “S”. Essentially, this gun was a 40 mm (1.57 in) developed in the late 1930s as an aircraft weapon and was a long-recoil design derived from the 37 mm 1½pdr “COW gun” from Coventry Ordnance Works. The ammunition was based on the 40x158R cartridge case of the naval 2 pdr Anti-Aircraft gun (the “Pom-pom”). The gun was originally intended as a bomber defensive weapon and had been tested as such in a turret fitted to a modified Vickers Wellington II. It had not adopted for service by the British, but Vickers were more than happy to sell a small number for testing.

After tests showed a high level of accuracy with an average of 25% of shots fired at tanks striking the target and achieving “kills”, the Ilmavoimat went ahead and placed an order with Vickers, as well as asking Hawker to install the guns in all the production aircraft. Attacks with HE were twice as accurate as with AP, possibly because the ballistics were a closer match to the machineguns used for sighting (the HE shell was lighter and was fired at a higher velocity).

The Henley’s were delivered in August 1938 and exceeded expectations considerably. Fitted with the Finnish-built Hispano-Suiza 12Y engines, they had a maximum speed of 300mph and were configured to carry 2x500lb bombs together with the two 40mm cannon pods, making them a lethal ground attack aircraft. So enthused was the Ilmavoimat with the performance of the aircraft that a further 20 were ordered in early 1939. These were produced at the tail-end of the British order for their “target tugs”and were delivered in late summer 1939.

Meanwhile, in RAF service, the Henley was not proving to be a great success as a target tug. With some 200 in service, it was discovered that the Merlin engine could not cope with high speed target towing. It was soon discovered that unless the aircraft were restricted to an unrealistically low tow speed of 220 mph (355 km/h), the rate of engine failures was unacceptably high. This resulted in Henley’s being withdrawn from this role and relegated to towing larger drogue targets with anti-aircraft co-operation units. Predictably, the Henley proved to be even more unsuited to this role, and the number of engine failures increased. Several Henley’s were lost after the engine cut-out and the drogue could not be released quickly enough. In September 1939, with war with the USSR looming unmistakably closer, the Finnish government made an urgent request to the British government to purchase a large number of the Henley “target tugs” – and undertook to pay for replacement Miles Master target tugs similar to those that had been built for them for glider towing by Phillips and Powis Aircraft Limited.

The Finns already had assurances in hand that Phillips and Powis Aircraft Limited were able to produce the Miles Master tugs rapidly (the Finns also undertook to take the Henley’s minus their engines – they would fit their own) and this taken together with the obvious unsuitability of the Henley for use as a target tug, resulted in the British agreeing to trade 80 Hawker Henley’s to Finland. Approximately half were crated and shipped in early November 1939 and arrived in Tampere some three weeks later, just prior to the attack on Finland by the USSR on the 30th of November 1939. A small stockpile of Hispano-Suiza 12Y engines had been built up and these were fitted after the shipment arrived. The other half of the order were flown to Finland “as is” in mid-December 1939 (after the Winter War had broken out) by Ilmavoimat Ferry Pilots, some of whom, to the amazement of the RAF and the delight of British newspapers, were women.

“She climbed out of the cockpit of her Hawker Henley Dive Bomber and became instantly famous. Wearing a summer uniform of white shirt, dark tie and sleeves rolled above the elbow, she slung a parachute over her shoulder and shook out her long blonde hair. Back-lit by the afternoon sun, Ilmavoimat Ferry Pilot Maureen Dunlop looked unbelievably glamorous.” One of the more memorable photos of the Winter War was a shot taken of a female Ilmavoimat Ferry Pilot taken just after a familiarization flight in one of the Hawker Henley’s that was to be transferred to Finland. The photo achieved widespread publication in the UK, the USA and France as well as in Italy and did much to boost the image of Finland as a courageous democracy fighting an all-out war against the Bolsheviks. The pilot was actually an Anglo-Argentinian volunteer, Maureen Dunlop, who had traveled from Buenos Aires to the UK where she had approached the Finnish Embassy and volunteered as a pilot. Desperately short of trained pilots and themselves already using women pilots for non-combat flights, the Finnish embassy accepted her after a flight test. Her first assignment was flying a Hawker Henley to Finland. She went on to fly for the Ilmavoimat for the duration of the Winter War before returning to the UK, where she flew as a ferry pilot for the British Air Transport Auxiliary.

Well after WW2, a novel came out that was very loosely based on Maureen Dunlop’s adventures during the Winter War and WW2.

OTL Note: It’s not. The author used the picture for the cover and it’s about female pilots with the ATA in WW2 but that’s about the sum total of the connection. It’s a great photo tho – it made the covers of Life and the UK’s “Picture Post” magazines. If you want to know more, read “The Spitfire Women of World War II” by Giles Whittell.

A number of additional Vickers “S”guns had been purchased earlier in the year – and Vickers had supplied these quickly. In Finland, the 40mm cannon pods were added and the bomb racks restored. The second seat was removed, if there was time the canopy was replaced, Ilmavoimat radios were installed and lastly, additional armour was retrofitted where available (which was only for about half the aircraft received, which was reason in part for the heavy losses these squadrons suffered over the Winter War).

Ilmavoimat Hawker Henley ground attack aircraft were nicknamed “Lentävä-purkinavaaja” by the Ilmavoimat Pilots who flew them (“Flying Can Opener”). With their 40mm cannon with only 12 rounds per gun, they were incapable of being used as fighters but their speed of around 300mph generally proved sufficient to get them out of trouble and the additional armour helped, although it didn’t stop them taking losses from Soviet AA guns where these existed and were used effectively (in the early months of the Winter War, this was not often).

The first of the ex-RAF Henley’s had modifications completed and began entering service in February 1940, at first replacing losses in the existing two Henley-equipped squadrons that had served so well over the first three months of the Winter War- by late February 1940 almost half of the 40 Henley’s in service at the start of the war had been shot down. Being the pilot of a “Lentävä-purkinavaaja” was a high-risk occupation with a low rate of survival. However, they were devastating ground attack aircraft, decimating attacking Soviet armor on any number of occasions as the Russians attacked and equally as dangerous to the enemy when the Finnish forces attacked. They saw service through to the end of WW2.

The Ilmavoimat Henley “Lentävä-purkinavaaja” later influenced the design of the A-10 Thunderbolt II, with Unto Oksala’s book, “Purkinavaaja Pilot” being required reading for all members of the A-X project, along with Hans Rudel’s “Stuka Pilot.”

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland