The Finnish Army faced enormous challenges in training the conscript citizen-soldier in the 1920’s and the 1930’s – the interwar years. The Army was supposed to organise and prepare for defending the country against vastly superior Russian forces. It had to train whole generations of young Finnish men into skilled soldiers and equip them for combat. Furthermore, it was expected to turn these men into the kind of highly motivated, patriotic, self-motivated and self-sacrificing modern national warriors envisioned by the Jägers and other officers in the younger generation. The starting point was none too promising, due to the criticism and scepticism in the political arena towards protracted military service within the cadre army system. Many conscripts from a working class background had all too probably seized on at least some of the socialists’ anti-militaristic or even pacifistic agitation against armies in general and bourgeois cadre armies in particular. Neither could conscripts from the areas of society supporting the Agrarian Party be expected to arrive at the barracks unprejudiced and open-minded. Although conscripts from families who were small freeholders usually supported the Civil Guards, they were not necessarily positive about military service within the cadre army, especially during the first years of its existence. In consequence, a majority of the conscripts, particularly in the 1920’s, could be expected to have an “attitude problem”. Some of the greatest challenges facing the conscript army were therefore to prove its efficiency as a military training organisation, convince suspicious conscripts and doubtful voters of its commitment to democracy, and demonstrate its positive impact on conscripts.

Although it was often claimed that military training as such would foster mature and responsible citizens – giving the conscripts discipline, obedience and punctuality as well as instilling consideration for the collective interest – officers and pro-defence nationalists with educationalist inclinations did not place their trust in close-order drill and field exercises alone. More had to be done. From the point of view of army authorities and other circles supportive of the regular army, there was an urgent need to “enlighten” the conscript soldiers. They had to be “educated” into adopting a positive attitude towards not only military service and the cadre army system, but also towards their other civic duties within the new “white” national state. This Post examines the attempts of officers, military priests and educationalists to offer the conscripts images of soldiering that would not only make conscripts disciplined, motivated and efficient soldiers, but also help the conscript army overcome its “image problems” and help the nation overcome its internal divisions. The Post’s focus is therefore not on the methods or practices of the educational efforts directed at the conscripts in military training, but on the ideological contents of these efforts, mainly as manifested in the intertwined representations of soldiering and citizenship in the army’s magazine for soldiers Suomen Sotilas (Finland’s Soldier).

Civic education and the Suomen Sotilas magazine

The 1919 report produced by a committee appointed by the Commander of the Armed Forces to organise the “spiritual care” of the conscripted soldiers expressed both the concerns felt over the soldiers’ attitude towards their military service and the solutions envisioned. The report stressed the importance in modern war of “the civil merit of an army, its spiritual strength”. In the light of “recent events” the committee pointed to the risks of arming men without making sure that they had those civil merits – a reference to the Civil War, perhaps, or to the participation of conscripted soldiers in the recent communist revolutions in Russia, Germany and other Central European countries. The report stated, “the stronger the armed forces are technically, the greater the danger they can form to their own country in case of unrest, unless they are inspired by high patriotic and moral principles that prevent them from surrendering to support unhealthy movements within the people”. The committee members – two military priests, two Jäger officers and one elementary school inspector – saw the remedy as teaching the conscripts basic knowledge about the fatherland and its history, giving those who lacked elementary education basic skills in reading, writing and mathematics, and providing the soldiers with other “spiritual pursuits”, which mainly meant various religious services. Quoting the commander of the armed forces, General K.F. Wilkama, the committee supported the notion that the army should be a “true institution of civic education”. Its optimistic report expressed a remarkably strong faith in the educational potential of military service.

These educational aspirations should be seen not only within the framework of not only the military system, but also as a part of the ongoing concerns among the Finnish educated classes over the civic education and political loyalties of the working class ever since the end of the nineteenth century. Urbanisation, industrialisation and democratisation made the perceived “irrationality” and “uncivilised” state of the masses seem ever more threatening to the elite. In face of the pressure towards “Russification” during the last decades of Russian rule, and the subsequent perceived threat from Soviet Russia, this anxiety over social upheaval was translated into an anxiety over national survival. Historian Pauli Arola has argued that the attempt by Finnish politicians to introduce compulsory elementary education in 1907 – after decades of political debate, but only one year after universal franchise was introduced – should be seen within the constory of these feelings of threat. Once the “common people” had the vote, educating them into “loyalty” in accordance with the upper classes’ notions of the “nation” and its existing social order became a priority. Resistance from imperial authorities stopped the undertaking in 1907, but Finnish educationalists continued to propagate for increased civic education through-out the school system.

The civil war only intensified the urgency of the educated elite’s agenda of educating the rebellious elements among the Finnish people. The intellectuals of “white” Finland described these as primitive, brutal, even bestial, hooligans who for lack of discipline and culture had become susceptible to Russian influences and given free rein to the worst traits in the Finnish national character. There was a special concern over children from socialist environments and the orphan children of red guardsmen who had died in the war or perished in the prison camps. When compulsory education was finally introduced in 1921, the curriculum for schools in rural districts, where most Finns then lived, was strongly intent on conserving the established social order. It idealised traditional country life in opposition to “unsound” urbanisation and emphasised the teaching of Christian religion and domestic history. In the same spirit, civic education was from the outset included in the training objectives of the conscript army. “Enlightenment lectures”, also called “citizen education”, were incorporated in the conscripts’ weekly programme. These lectures were sometimes given by officers, but mainly by military priests (who were also assigned the duty of teaching illiterate conscripts to read and write.

As elementary schooling was only made compulsory in 1921, the army throughout the interwar period received conscripts who had never attended elementary school. The share of illiterate conscripts was however only 1–2%, peaking in 1923 and thereafter rapidly declining. Nevertheless, in 1924 elementary teaching still took up ten times as many working hours for the military priests as their “enlightenment work”). In 1925, the Commander of the armed forces issued a detailed schedule for these lectures. The conscripts should be given 45 hours of lectures on the “history of the fatherland”, 25 hours on civics, 12 hours on Finnish literary history and 10 hours of lectures on “temperance and morality”. Taken together, roughly two working weeks during the one-year military service were consequently allocated for civic education. In addition, the pastoral care of the soldiers, in the form of evening prayers and divine service both in the garrisons and training camps, was seen as an important part of “enlightening” soldiers. A consciousness of the nation’s past and religious piety were evidently een as the two main pillars of patriotism, law-abidingness and loyalty to the existing social order. (The dean of the military priests Artur Malin presented the ongoing civic education work in the army in an article in the Suomen Sotilas magazine in 1923. He listed the following subjects: reading, writing, mathematics, geography, history, civics, natural history, singing, handicraft and temperance education).

The Army’s Magazine for Soldiers

In most army garrisons and camps, local female volunteers provided a service club or “Soldiers’ home”. These establishments offered coffee, lemonade and bakeries, but also intellectual stimulus in the form of newspapers, magazines and small libraries. Any socialist or otherwise “unpatriotic” publications were unthinkable in these recreational areas where the conscripts spent much of their leisure hours. However, one of the publications the conscripts would most certainly find at the “Soldiers’ Home”, if it wasn’t already distributed to the barracks, was the weekly magazine Suomen Sotilas (Finland’s Soldier). This illustrated magazine contained a mixture of editorials on morality, military virtues and the dangers of Bolshevism, entertaining military adventure stories, and articles on different Finnish military units, sports within the armed forces, military history, weaponry and military technology. There were reviews on recommended novels and open letters from “concerned fathers” or “older soldiers”, exhorting the conscripts to exemplary behaviour, as well as a dedicated page for cartoons and jokes about military life. The interwar volumes of Suomen Sotilas serve as a good source on the “enlightenment” and “civic education” directed at the conscript soldiers within the military system. Through its writers, the magazine was intimately connected with the command of the armed forces, yet formally it was published by an independent private company.

The editors in chief were literary historian Ilmari Heikinheimo (1919–1922), student of law and later Professor of Law Arvo Sipilä (1922–1925), M.A. Emerik Olsoni (1926) and army chaplain, later Dean of the Army Chaplains Rolf Tiivola (1927–1943). Important writers who were also Jäger officers were Veikko Heikinheimo, military historian and Director of the Cadet School Heikki Nurmio, Army Chaplains Hannes Anttila and Kalervo Groundstroem, as well as Aarne Sihvo, Director of the Military Academy and later Commander of the Armed Forces. Articles on new weaponry and military technology were written by several Jäger officers in the first years the magazine was published; a.o. Lennart Oesch, Eino R. Forsman [Koskimies], Verner Gustafsson, Bertel Mårtensson, Väinö Palomäki, Lars Schalin, Arthur Stenholm [Saarmaa], Kosti Pylkkänen and Ilmari Järvinen. All of these officers had successful military careers, reaching the rank of Lieutenant Colonel or higher. In the last number of the first volume of 1919, the editors published the photographs of 13 of the magazine’s “most eager collaborators”. Out of these 13, nine were officers, five were Jäger officers. The five civilians were a Master of Arts, two Doctors of Philosophy and one clergyman.

The initiative for starting the magazine originally came from the war ministry and the contents of each number were initially examined before publication by ministry officials. In 1919–1921, the magazine was published by a small publishing house for popular enlightenment, Edistysseurojen (as this publisher went bankrupt in 1923, the editors formed a public limited company, ‘Kustannus Oy Suomen Mies’ (~Finland’s Man Publishing Company Ltd.) which took over the magazine. On the tenth anniversary of the magazine’s founding, its chief accountant complained that the state had not subsidised the magazine at all in 1919–1925 and then only granted a minimal subsidy) and regular writers were mostly nationalist officers of the younger generation, many of them either Jäger officers or military priests. Civilians – professional authors, historians, educators and clergymen – also wrote for the magazine, but usually more occasionally rather than regularly. In spite of different backgrounds and experiences, the contributors had a lot in common; they were generally educated middle-class men who shared a staunchly non-socialist and nationalist political outlook. Contributions from female authors were not unheard of, but rarely occurred.

Although the magazine was meant to be published weekly, it was published fortnightly over several long periods. The support of private business was important for its economy, both through advertising revenue and gift subscriptions to the military units paid for by defence-friendly businessmen. The magazine started out with a circulation of 4 000 in 1919 and rose to over 12,000 by mid-1920. This caused the editors to proudly exclaim: “Now it can be said with certainty that Suomen Sotilas falls into the hands of every soldier and civil guardsman.” After the magazine’s first 18 months these rather frequent notices on the circulation ceased to appear, probably indicating that the circulation had started to decline. Originally aimed at a readership of both conscripts and civic guards, the magazine had to give in to the tough competition from other magazines for Suojeluskuntas readership after a few years. It then concentrated on being the army’s magazine for soldiers.

The contents of Suomen Sotilas not only express the hopes and objectives of some of the same people who were in charge of training and educating the conscripted soldiers, but also their concerns and fears with regard to conscripts. In its first number, the editors of Suomen Sotilas proclaimed that the ambition of the magazine was to “make the men in the ranks good human beings, good citizens and good soldiers”. Its writings should serve “general civic education and completely healthy spiritual development” and strive towards “the fatherland in its entirety becoming dear to and worth defending for our soldiers.” A concern about lacking patriotism or even hostility towards the national armed forces can, however, be read between these lines. This concern did not diminish much during the 1920’s, but was stated even more explicitly by the former editor-in-chief Arvo Sipilä (1898–1974) in the magazine’s tenth anniversary issue in December 1928: “It is well known, that among the youths liable for military service there are quite a number of such persons for whom the cause of national defence has remained alien, not to speak of those, who have been exposed to influences from circles downright hostile to national defence. In this situation, it is the natural task of a soldiers’ magazine to guide these soldiers’ world of ideas towards a healthy national direction, in an objective and impartial way, to touch that part in their emotional life, which in every true Finnish heart is receptive to the concept of a common fatherland (…)”

The editors of Suomen Sotilas were painfully aware of the popular and leftist criticism of circumstances and abuses in the army throughout the 1920’s. In 1929 an editorial lamented, “the civilian population has become used to seeing the army simply as an apparatus of torture, the military service as both mentally and physically monotonous, the officers as beastlike, the [army’s] housekeeping and health care as downright primitive.” The same story greeted the recent PR drive of the armed forces, inviting the conscripts’ relatives into the garrisons for “family days”. There, the editorial claimed, they would see for themselves that circumstances were much better than rumour would have it. The initiative behind these “family days”, however, arose from the officers’ intense concerns over the popular image of the conscript army17 – concerns that were also mirrored in the pages of Suomen Sotilas (According to historian Veli-Matti Syrjö, the ”family days” was an initiative by Lieutenant-Colonel Eino R. Forsman. In his proposal, Forsman pointed out how an understanding between his regiment and the civilian population in its district was obstructed by popular ignorance).

Turning a Conscript into a Citizen-Soldier

In the autumn of 1922, the First Pioneer Battalion in the city of Viipuri arranged a farewell ceremony for those conscript soldiers who had served a full year and were now leaving the army. On this occasion, the top graduate of the Finnish Army’s civic education training gave an inspiring speech to his comrades. – At least, so it must have seemed to the officers listening to Pioneer Kellomäki’s address, since they had it printed in Suomen Sotilas for other soldiers around the country to meditate upon. This private told his comrades that the time they had spent together in the military might at times have felt arduous, yet “everything in life has its price, and this is the price a people has to pay for its liberty”. Moreover, he thought that military training had no doubt done the conscripts well, although it had often been difficult and disagreeable: “You leave here much more mature for life than you were when you arrived. Here, in a way, you have met the reality of life, which most of you knew nothing about as you grew up in your childhood homes. Here, independent action has often been demanded of you. You have been forced to rely on your own strengths and abilities. Thereby, your will has been fortified and your self-reliance has grown. In winning his own trust, a man wins a great deal. He wins more strength, more willpower and vigour, whereas doubt and shyness make a man weak and ineffective. You leave here both physically hardened and spiritually strengthened.” This talented young pioneer had managed to adopt a way of addressing his fellow soldiers that marked many ideological story’s in Suomen Sotilas. He was telling them what they themselves had experienced and what it now meant to them, telling them who they were as citizens and soldiers. His speech made use of two paired concepts that often occurred in the interwar volumes of the magazine. He claimed that military education was a learning process where conscripts grew into maturity and furthermore, that the virtues of the good soldier, obtainable through military training, were also the virtues of a useful and successful citizen.

What supposedly happened to conscripts during their military service that made them “much more mature for life”? In the army, conscripts allegedly learned punctuality, obedience and order, “which is a blessing for all the rest of one’s life”. Sharing joys and hardships in the barracks taught equality and comradeship. “Here, there are no class differences.” The exercises, athletics and strict order in the military made the soldiers return “vigorous and polite” to their home districts, admired by other young people for their “light step and their vivid and attentive eye.” Learning discipline and obedience drove out selfishness from the young man and instilled in him a readiness to make sacrifices for the fatherland. The duress of military life hardened the soldier, strengthened his selfconfidence and made “mother’s boys into men with willpower and Stamina.” The thorough elementary and civic education in the army offered possibilities even for illiterates to succeed in life and climb socially (1929).24 The order, discipline, exactitude, cleanliness, considerateness, and all the knowledge and technical skills acquired in the military were a “positive capital” of “incalculable future benefit” for every conscript – there was “good reason to say that military service is the best possible school for every young man, it is a real school for men, as it has been called.” “If we had no military training, an immense number of our conscripts would remain good-for-nothings; slouching and drowsy beings hardly able to support themselves. [The army] is a good school and luckily every healthy young man has the opportunity to attend it.” (All quotes from various articles in Suomen Sotilas magazine).

It is noteworthy how the rhetoric in Suomen Sotilas about military service improving conscripts’s minds and bodies usually emphasised the civic virtues resulting from military training. Military education was said to develop characteristics in conscripts that were useful to themselves later in life and beneficial for civil society in general. Conscripts being discharged in 1922 were told that experience from the previous armed forces in Finland had proven that the sense of duty, exactitude and purposefulness in work learnt in military service ensured future success in civilian life as well. If the conscripts wanted to succeed in life, they should preserve the values and briskness they had learnt in the army, “in one word, you should still be soldiers”. Such rhetoric actually implied that the characteristics of a good soldier and a virtuous citizen were one and the same. As the recruit became a good soldier, he simultaneously developed into a useful patriotic citizen. The Finnish Army, an editorial in 1920 stated, “is an educational institution to which we send our sons with complete trust, in one of the decisive periods of their lives, to develop into good proper soldiers and at the same time honourable citizens. Because true military qualities are in most cases also most important civic qualities.” If the army fulfilled this high task well, the story continued, the millions spent in tax money and working hours withheld would not have been wasted, but would “pay a rich dividend.”

Storys in this vein were most conspicuous in Suomen Sotilas during the early 1920’s, as conscription was still a highly controversial issue and heated debates over the shaping of military service went on in parliament. In 1922, just when the new permanent conscription law was waiting for a final decision after the up-coming elections, an editorial in the magazine expressed great concerns over the possibly imminent shortening of military service.

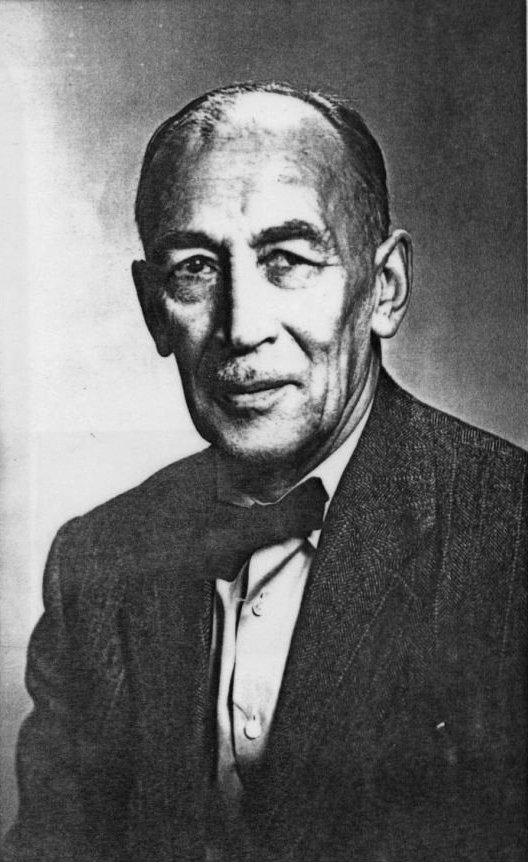

Paavo Virkkunen (27 September 1874, Pudasjärvi – 13 July 1959, Pälkäne) was a Finnish conservative politician. He was a member of the Finnish Party and was elected in the parliament in 1914, but joined the National Coalition Party (Kokoomus) in 1919. He was five times the Speaker of the Parliament. He became the chairman of the party in 1932 following the six year leadership of Kyösti Haataja.

The editors blamed the “suspicious attitude” among the public towards the conscript army on negative prejudices caused by the old imperial Russian military. The contemporary military service, they claimed, was something quite different. It was a time when conscripts “become tame”, realised their duty as defenders of the fatherland, improved their behavior and were united across class borders as they came to understand and appreciate each other’s interests and opinions. All these positive expectations can be read as mirroring anxieties among the educated middle classes over continued class conflicts in the wake of the Civil War and the lack of patriotism and a “sense of duty” among conscripts in the working classes. The assurances that military service would inevitably induce the right, “white” kind of patriotism and civic virtue in conscripts and unite them in military comradeship appear to be fearful hopes in disguise.

As late as 1931, the conservative politician Paavo Virkkunen wrote in Suomen Sotilas that the bitterness “still smouldering in many people’s mind” after the events in 1918 had to give place for “positive and successful participation in common patriotic strivings”. He saw conscripts divided by political differences and hoped that they would be united by the common experience of military service, “a time of learning patriotic condition” and “a fertile period of brotherly comradeship and spiritual confluence.”

Physical Education

Moral education and physical development were closely intertwined in the public portrayal of how military service improved conscripts. The military exercises, it was claimed, would make the conscripts’ bodies strong, healthy and proficient. In 1920, the committee for military matters in parliament made a statement about the importance for national security of physical education for conscripts. Pleading to the government to make greater efforts in this area, the committee pointed out how games, gymnastics and athletics not only generated the “urge for deeds, drive, toughness and readiness for military action” in the nation’s youth, but also developed discipline, self-restraint and a spirit of sacrifice. The conscript should be physically trained and prepared for a future war in the army, as well as being developed and disciplined into a moral, industrious and productive citizen. The militarily trained conscript, claimed Suomen Sotilas in 1920, was handsome and energetic, aesthetically balanced, harmonious, lithe and springy – unlike the purely civilian citizen, who was marked by clumsiness, stiff muscles and a shuffling gait.

Klaus Uuno Suomela (last name until 1906 Lindholm , November 10, 1888 in Porvoo – April 4, 1962 Helsinki ) was a Finnish gymnast, physical educator, doctor of philosophy, and sports writer. he was a co-founder in 1917 of the Helsinki Suojeluskuntas and a Battalion commander in the Civil War. Between 1918-1931 he was a lecturer at the University of Helsinki, also gymnastics instructor to 1955. He wrote the play, Hopeakihlajaiset which was made into a film in 1942.

According to Klaus U. Suomela, a leading figure in Finnish gymnastics writing in the magazine in 1923, the lack of proper military education and the hard toiling in agriculture and forestry had given many Finns a bad posture and unbalanced bodily proportions. Their arms, shoulders and backs were overdeveloped in relation to the lower extremities. Gymnastics to the pace of brisk commands as well as fast ball games and athletics would rectify these imperfections and force the Finns, “known to be sluggish in their thinking”, to speed up their mental activities, Suomela stated. He admitted that “the Finnish quarrelsomeness” would be worsened by individual sports, but this would be counteracted by group gymnastics and team games. Suomela seems to have viewed Finnish peasant boys from the vantage point of the athletic ideals of the educated classes, emphasising slenderness, agility and speed, and found them too “rough-hewn and marked by heavy labour”.

After independence and the Civil War, Finnish military and state authorities immediately saw a connection between security policy, public health and physical education. Officers and sports leaders debated how gymnastics and athletics formed the foundations for military education. Proposals to introduce military pre-education for boys in the school system were never realised, but physical education in elementary schools and the civil guards nonetheless emphasized competitive and physically tough sports in the 1920’s and 1930’. These “masculine” sports were thought to develop the strength and endurance needed for soldiering. Light gymnastics, on the other hand, were considered more appropriate for in schoolgirls, developing “feminine” characteristics such as bodily grace, nimbleness and adaptation to the surrounding group. Sports and athletics were given lavish attention in Suomen Sotilas.

The magazine reported extensively on all kinds of sports competitions within the armed forces, publishing detailed accounts and photographs of the victors. Sports were evidently assumed to interest the readership, but the editors also attached symbolical and political importance to sports as an arena of national integration. An editorial in 1920 claimed that in the army sports competitions, ”Finland’s men could become brothers” as officers and soldiers, workers and capitalists competed in noble struggle. “There is a miniature of Finland’s sports world such as we want to see it – man against man in comradely fight, forgetful of class barriers and class hate. May the soldiers take this true sporting spirit with them into civilian life when they leave military service.” Hopes were expressed that conscripts, permeated with a patriotic sense of duty after receiving their military education, would continue practicing sports and athletics in their home districts, not only to stay fit as soldiers and useful citizens, but also in order to spread models for healthy living and physical fitness among the whole people.

The Immaturity of Recruits

The rhetoric about the army as a place where boys became men and useful, responsible citizens required a denial of the maturity and responsibility of those who had not yet done their military service. The 21-year old recruits who arrived for military training, many of them after years of employment, often in physically demanding jobs requiring self-management and responsibility, were directly or indirectly portrayed as somehow less than men, as immature youngsters who had not yet developed either the physique or the mind of a real man. In this constory, the writers in Suomen Sotilas took the moral position of older and wiser men who implicitly claimed to possess the knowledge and power to judge young soldiers in this respect. Any critique or resistance against the methods of military service was dismissed and ridiculed as evidence of immaturity or lack of toughness. “You know very well that perpetual whining does not befit a man, only women do that”, wrote an anonymous “Reservist” in 1935 – i.e. somebody claiming to already have done his military training. An “Open letter to my discontented son who is doing his military service” in 1929 delivered a paternal dressing-down to any reluctant conscript, claiming that the only cause for discontent with army life was a complete lack of “sense of duty”. The military, however, provided a healthy education in orderliness and the fulfilling of one’s duties, taking one’s place in the line “like every honourable man”.

This immaturity of the Finnish conscript was sometimes described as not only a matter of individual development, but also associated with traits of backwardness in Finnish culture and society, which could, however, be compensated for both in individuals and the whole nation by the salubrious effects of military training. It was a recurring notion that Finns in layers of society without proper education had an inclination to tardiness, slackness and quarrelsomeness. This echoed concerns over negative traits in the Finnish national character that had increased ever since the nationalist mobilisation against the Russian “oppression” encountered popular indifference. The spread of socialism, culminating in the rebellion of 1918, made the Finnish people seem ever more undisciplined and inclined to envy, distrustfulness and deranged fanaticism in the eyes of the educated elites. In an article published in 1919, Arvi Korhonen (1897–1967), a history student and future professor who had participated in the Jäger movement as a recruiter, complained about the indolence and lack of proficiency and enterprise of people in the Finnish countryside.

Korhonen called for military discipline and order as a remedy for these cultural shortcomings. “Innumerable are those cases where military service has done miracles. Lazybones have returned to their home district as energetic men, and the bosses of large companies say they can tell just from work efficiency who has been a soldier.” Korhonen claimed that similar observations were common enough – he was evidently thinking of either experiences from the “old” conscript army in Finland or from other countries – to show that “the army’s educational importance is as great as its significance for national defence.” Another variation on this theme ascribed a kind of primordial and unrefined vitality to Finnish youngsters, which had to be shaped or hardened by military training in order to result in conduct and become useful for society. The trainer of the Finnish Olympic wrestling team Armas Laitinen wrote an article in this vein in 1923, explaining why the military service was a particularly suitable environment to introduce conscripts to wrestling: “Almost without exception, healthy conscripts arrive to the ranks and care of the army. The simple youngsters of backwoods villages arrive there to fulfil their civic duty, children of the wilds and remote hamlets, whose cradle stood in the middle of forests where they grew to men, healthy, rosy-cheeked and sparkling with zest for life. In the hard school of the army they are brought up to be men, in the true sense of the word, and that common Finnish sluggishness and listlessness is ground away. Swiftness, moderation and above all vigour are imprinted on these stiff tar stumps and knotty birch stocks. They gradually achieve their purpose – readiness. The army has done its great work. A simple child of the people has grown up to a citizen aware of his duty, in which the conscious love of nationalism has been rooted forever.”

Jääkärikapteeni Kalervo Groundstroem: Lauri Kalervo Groundstroem myöh. Kurkiala (16. marraskuuta 1894 Längelmäki – 26. joulukuuta 1966.

Jäger lieutenant and student of theology Kalervo Groundstroem (1894–1966) was even less respectful towards the recruits when he depicted the personal benefits of military training in 1919. In the army, he wrote, everything is done rapidly and without any loitering, “which can feel strange especially for those from the inner parts of the country”.

“It is very salutary that many country boys, who all their lives have just been laying comfortably next to the fireplace, at last get a chance to rejuvenate and slim themselves. And we can only truly rejoice that numerous bookworms and spoilt, sloppy idlers get an airing by doing field service. Barracks life and the healthy influence of comradeship rub off smallmindedness, selfishness, vanity and other “sharp edges” in a young man’s character”, claimed Groundstroem. Military training is therefore “a useful preparation for future life.” Moving in step with others, the soldiers acquire a steady posture, their gaze is strengthened, their skin gets the right colour, they always have a healthy appetite, and flabby muscles are filled out and tightened. The finest result of this education, however, is the “unflinching sense of duty” it brings forth. The “sense of duty” mentioned in many of the quotes above stands out as the most important shared quality or virtue of the ideal soldier and citizen. From this military and civic virtue, the other characteristics of a good soldier and a good citizen quoted so far could be derived, such as self-restraint, a spirit of sacrifice, order and discipline, punctuality and exactitude in the performance of assigned tasks, unselfishness and submitting to the collective good, etc. The writers in Suomen Sotilas usually positioned themselves through their storys as superior to the readers in knowing what duty meant and hence entitled, indeed obliged, to educate the readers, who were positioned as thoughtless yet corrigible youngsters. In the constory of Suomen Sotilas, references to “a sense of duty” conveyed a message to the individual man that he needed to submit himself and his actions in the service of something higher and larger than his own personal desires and pleasures – submit to the army discipline and to the hardships and dangers of soldiering.

A Sense of History and a Spirit of Sacrifice

A vast array of storys and pictures in Suomen Sotilas were intent on conveying a sense of national history and military traditions to the readers. The magazine abounded with histories of Finnish military units and tales of battles and campaigns where Finns had fought, all the way from the times of the national epic Kalevala and the Iron Age up until the Liberation War and the Heimosodat (Kinship Wars) of 1918–1922. The stories of the hakkapeliitta Finnish cavalrymen of Gustavus II, the Finnish soldiers of Charles XII, the soldiers and officers of the Finnish War 1808–1809 as portrayed by Runeberg, and the Jägers and other heroes of 1918 were tirelessly retold. This national military heritage was iterated through different genres, both as factual military history and as fictional adventure stories. The recurrent theme was that Finns had always been good soldiers; strong, unyielding and fearless, who did not hesitate to sacrifice their lives for their military honour or their freedom.

According to Heikki Nurmio, who was a central figure both within military education and military historiography in the 1920’s, it was important to make the conscripts aware of these historical traditions since they were sources of “national military spirit and soldier virtues” for the young army. However, he balanced the glorification of Finnish soldierhood by pointing out that they illustrated both the strengths and the weaknesses of Finnish men as soldiers. In the same spirit, Olavi Uoma wrote that the 17th century hakkapeliitta cavalrymen had understood that the Finns’ many defeats in the border clashes with neighbouring peoples had derived from a spirit of passivity and defensiveness. For that reason the hakkapeliittas had assumed a “spirit of the offensive”, which they had left as an “invaluable heritage” to their descendants. “The smaller our number, the more ruthlessly we have to attack, if we want to pull through”, enjoined Uoma of the readers, obviously trying to prepare them for confronting a Soviet attack.

Recurring references to the Finnish “forefathers” upheld a historical myth where these anonymous forefathers for hundreds of years had not only fought Swedes and Russians, but also striven for an independent state. One typical such story from 1929 put conscription in the constory of Finnish men fighting and prevailing over superior forces throughout the centuries. It related the words of a grandfather, explaining to his grandson about how the men of their home village resisted the Russian Cossacks in the past. The old man urges the boy to remember that their village has been burnt dozens of times by the Eastern enemies, “… and you can count by many hundreds the men of your tribe who over the centuries have sacrificed their lives to drive out the oppressors from this neck of the woods. The land we call our own was bought with the heart-blood of our fathers. A Finnish man will not bear a foreign yoke and nothing but death breaks his perseverance. (…) You too, my boy, will grow up to be a man and then you should know what you are obliged to by the deeds of the fathers of your tribe. Foreign feet must not trample the land that for centuries has drunk the blood of men defending their freedom.”

One can also see references to the “fore-fathers” in a number of patriotic songs of the period. A good example is Lippulaulu (The Flag Song), where the words for one of the verses are:

Fathers and brothers with their blood

inaugurated you as a banner for free country.

With joy we follow you

on roads traveled by our fathers

Siniristilippumme, (Our blue-crossed flag)

sulle käsin vannomme, sydämin: (for You we swear the oath:)

sinun puolestas elää ja kuolla (To live and die for You)

on halumme korkehin. (is our greatest wish.)

Kuin taivas ja hanki Suomen (Like the sky and snows of Finland)

ovat värisi puhtahat. (your colors are pure.)

Sinä hulmullas mielemme nostat (With your streaming you rouse our minds)

ja kotimme korotat. (and strengthens our homes.)

Isät, veljet verellään (Fathers and brothers with their blood)

vihki sinut viiriksi vapaan maan. (inaugurated you as the banner of our free country.)

Ilomiellä sun jäljessäs käymme (With joy we follow you)

teit’ isäin astumaan. (on the road traveled by our fathers.)

Sun on kunnias kunniamme, (Your glory is our honor,)

sinun voimasi voimamme on. (your strength is ours.)

Sinun kanssasi onnemme jaamme (With you we share our happiness)

ja iskut kohtalon. (and the blows of destiny.)

Siniristilippumme, (Our blue-crossed flag,)

sulle valan vannomme kallihin: (for You we swear the oath:)

sinun puolestas elää ja kuolla (To live and die for You)

on halumme korkehin. (is our greatest wish.)

Ardent Finnish nationalists in the interwar period thought Finland had now regained an independence lost in the dark Middle Ages to conquering Swedes and later Russians. For many zealots, “the political situation emerging in 1917–1918 was a return to an ancient, ethnic truth”. Although the idea of a Great National Past lost some of the heated intellectual topicality it had had during the decades before independence, it reached new levels of popularisation during the interwar period. Historical novels were a vogue in the 1930’s, accompanied by a multitude of new publications for boys presenting adventures in prehistorical and medieval Finland. The military aspects of the ancient Finns were made “a veritable trade mark of the republic” after independence. Warlikeness was made a predominant feature of ancient Finnish society in stories and visual representations in novels, magazines and even public monuments. The distant national past became “a fully militarised mirror of contemporary society” as the ancient Finns were portrayed as fighting the same battles that modern Finns were told to prepare themselves for. Incidentally, the magazine of the Lotta Svärd organisation contained similar representations of female heroes in the past (Seija-Leena Nevala, Lotta Svärd-aikakauslehti isänmaallisille naisille vuosina 1929–1939, Unpublished Master’s thesis).

Using history to challenge and encourage Conscripts

The militarised portrayal of the nation’s past was used to put the magazine’s readers under a moral obligation to honour their forefathers’ sacrifices by continuing their heroic struggle. Making a rather liberal interpretation of historical facts, Heikki Nurmio in 1924 portrayed the fight for national freedom as a historical mission, which had to be made clear to the conscripts through historical education: “With the roar of thunder, these [historical memories] speak immense volumes to us about Finland’s centuries-long struggle towards freedom and national independence, a struggle for which generation after generation, towns and countryside, noblemen, clergymen, peasants and the poorest tenant farmers and workmen of the backwoods in ancient times have uncompromisingly sacrificed everything they had. Those passed-away generations demand the same of the present generation and knowledge of their destiny is the best way of making clear the historical mission of the Finnish people.”

In the pages of Suomen Sotilas, this mission was naturally centred on the duty of conscripts to do their military service without complaint and prepare to go to war if needed. There was a “tax to be paid”, in the form of military service, to the fore-fathers who had toiled and suffered to make the barren land fruitful and prepare a way for Finland’s freedom. The debt to the men of the past could, however, also be used for other moral appeals, such as calling for national unity after the divisive events of 1918. The memory of the deaths of the heroes of 1918 “binds each and every one of us to take care that their sacrifice is not allowed to go to waste”, claimed an article in 1921 bearing the headline “The Memory of the Heroes of Liberty” – “The memories of the freedom fight are the most sacred memories our people have; they have to be cherished and left as our heritage to coming generations, who have to be taught their holy obligation to likewise sacrifice all their strength for preserving Finland’s independence and freedom.”

These articles in effect presented an implicit challenge to conscripts. In order to step into the timeless chain of Finnish history, they had to do what their fore-fathers had done, dare what they had dared, sacrifice what they had sacrificed. “Is the present military service really such a heavy burden that the present youth, parading its sports activities, cannot bear it upright, or were our fore-fathers after all of hardier stock in spite of the lack of sports?” scorned an “Uncle” in 1931. Through the portrayal of the forefathers as indomitable warriors, defending the land that they had cleared and tilled through tireless labour, a standard for “real” Finnish soldiers was set and the conscripts were challenged to demonstrate that they met this standard: “We read stories about men, who have died smiling knowing that they have done a service to the country they love. Conscripts! We don’t want to be inferior to them, because this land and this people are dear to us too. We do as our forefathers have done, like all real men in the world have done and always will do, we fight for the country and the people when it is in peril.

This standard was even sometimes given a name: “the spirit of the fathers”. A 1920 short story by Jäger Captain Kaarle Massinen told about an old man who gave a real scolding to the Red Guards confiscating his land during the Civil War. The old man called the guardsmen “sluggards” and stated that they never would have bothered to work those fields the way he had done. “The spirit of the fathers, the Finnish farmer who had always lived free from serfdom, had erupted like a volcano”, Massinen declared and suddenly turned to address the reader: “Finland’s soldier, you, who labour in the barracks, sometimes at your rifle, sometimes over a book, does the spirit of the fathers live in you?” Many of the stories about the forefathers’ valour and the spirit of the fathers also encouraged conscripts, assuring them that they did have what it took to be a warrior. The story quoted above, calling out to conscripts “we don’t want to be inferior to them”, actually continued by urging the reader to “let your best inner voice speak to you, let your natural, inherited instincts affect you”. Then, claims the author, you will “assuredly” find the courage and willingness to defend this country. The “spirit of the fathers” was thus portrayed as not only a model and example for present generations, but as somehow inherent in Finnish men.

We see this also reflected in music from the period, another good example being a song originating from the Civil Wat era, “Vapaussoturin Valloituslaulu” (Conquest song of a Civil War Freedom Fighter), written about the southern Ostrobothnia Jaeger legend and veteran of seven wars Antti Isotalo (1895-1964), and his reputation as a soldier and warriot. Isotalo served as a Jäger volunteer in the First World War on the German eastern front in 1916, fought in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, the Olonets Expedition in 1919, the Porajärven suojelusjoukoissa 1919-1920, Viena Karelia, 1921-1922, and the Winter and the Continuation War. His audacious military exploits were well known to all Finns.

Kauvan on kärsitty ryssien valtaa (We have long suffered Russkie rule)

Suomen kansan vapautta suojellessa. (Protecting the freedom of the Finnish people.)

Ylös pojat Pohjanmaan! (Rise Ostrobothnian boys!)

Urhot kalliin Karjalan! (Heroes of dear Karelia!)

Jäämit ja Savon miehet rintamahan! (Jäämis and men of Savo join the front!)

Sotahan nyt marssimme kotikulta jääköön (We are marching to war leaving our dear home)

Jääkäriveri tässä velvoittaa. (Our Jaeger blood obliges us.)

Ylös veljet valkoiset! (Rise White brothers!)

Alas ryssät punaiset! (Down Red Russkies!)

Ei auta vihamiestä armahtaa! (No mercy to the enemy!)

Voittoja väkeviä saatu jo monta (We have already gained many costly victories)

Meillä on Valkoisessa Suomessa: (In our White Finland:)

Oulu olkoon omamme! (Oulu is ours!)

Vaasa varsin varmamme! (Vaasa is ours for sure!)

Viipuria vastahan nyt vierimme! (Against Vyborg we are now rolling!)

Veriset on taistelut takanamme käyty (Bloody battles are behind us)

Kuka heitä kaikkia muistaakaan (Who will remember them all)

Vaskivesi, Varkaus! (Vaskivesi, Varkaus!)

Mäntyharjun harppaus! (Leap of Mäntyharju!)

Karjalan kaikkivoipa varjelemus! (Almighty guardian of Karelia!)

Hannilan harjuilla pommit ne paukkuu! (On Hannila’s ridges bombs are banging!)

Raudussa shrapnellit räiskähtelee! (In Rautu shrapnel’s crackling!)

Ahvola se ankarin! (Ahvola is most severe!)

Suninmäki sankarin! (Suninmäki most heroic!)

Pullilankin punikit viel’ rangaistaan! (Pullila Reds will be punished!)

Tulkohon ryssiä tuhannen tuhatta! (Russkies may come in the thousand thousands!)

Karjalan armeija kestää sen. (The Karelian Army can take it.)

Aika on jo ahdistaa! (It is time to pursue!)

Punakaartit puhdistaa! (Clean out the Red Guards!)

Venäläisen verikoiran karkoittaa! (Expel Russian blood hounds!)

Kuolema korkea – sankarin palkka! (High death – hero´s pay!)

Urhojen haudoilla hurratahan. (The heroes´graves will be remembered.)

Ruumis saakoon haavan vaan! (A body may just be wounded!)

Kuulat käykööt kulkuaan! (Bullets may fly their way!)

Sielu jääpi perinnöksi syntymämaan. (Their soul will stay as a heritage of the motherland.)

Viaporin linnahan leijonalippu (Over Suomenlinna’s fortress the Lion Flag)

Jukoliste, poijat, me nostetahan! (Goddamn, boys, we will hoist it!)

Suomen voimat näytetään! (Finland´s forces are we!)

Keinot karskit käytetään! (We use harsh means!)

Jääkäriveri tässä velvoittaa! (Our Jaeger blood obliges us!)

An anonymous “Jäger”, writing an editorial for Suomen Sotilas in 1935, claimed that the “spirit of the fathers” had aroused the “mighty White Army” in 1918 and restored order, safety, legality and freedom to the country. He described this spirit as both “solemn and binding” and a “firm and lasting heritage”, descending all the way from the battles of the Thirty-Years War and the Great Nordic War, indeed from the distant battles of “the age of sagas”. Yet this spirit, he explained, was not only a military spirit, but also the spirit of the peaceful work that had built the country. “That work has asked for fitness and skill, manliness and grandness just as much as defending the country.” Again, we that the very same spirit that had made the forefathers such formidable warriors had allegedly also been their driving force as they cleared and built the land. The success of Finnish athletes on international sports arenas during the 1920’s and 1930’s were used in Suomen Sotilas in the same way as the feats of the mythic forefathers; to convey a sense of a national community characterised by the physical and psychic qualities demonstrated by these sports heroes. Niilo Sigell wrote that the Finnish athletes who won several medals in the Olympic Games in Antwerp in 1920 were expressions of “the toughness, endurance, strength and vigour of our tribe” and “the force and power of character that has transformed the grim wildernesses of the north into abodes of human cultivation and endured hard times of war, hunger and pestilence”. In these athletes, Sigell found the same national character that had manifested itself in the heroes of the Thirty Years War or the Liberation War.

A story about the Finnish achievements in the Olympics in 1924 pointed to the “healthy life in the countryside” where most Finns still resided and referred to the Finns as a people that had “toiled in woodlands and skied through wildernesses”. Connecting the Finnish nature, landscape and climate with the national character, sports achievements and military virtues, these writings evidently aimed at infusing the readers with pride and confidence in the inherent strength of their people, implying the Finns could fend off a quantitatively superior enemy by virtue of their superior quality as soldiers. Writer and historian Jalmari Finne even explained the extraordinary bravery of Finnish men in battle, throughout the centuries, as deriving from the tranquil life of a nation of farmers. The sedate life and taciturnity of the Finns, he explained, built up a storage of strength and energy waiting for a discharge. “An opportunity to fight has been like a relief. … Battle is the place where a Finn feels all his inner strength blossoming, a moment of rejoicing. … Bravery, the highest and most beautiful expression of manliness, is in the Finn’s blood and only needs an opportunity [to emerge] and then it seems to astonish other [peoples].”

When historian Einar Juvelius introduced a new series of articles on Finnish history in 1920, he expressed his hope that the commencing series would encourage young soldiers to acquaint themselves with their forefathers’ “unwavering readiness and irrepressible faith in the future – the same readiness and faith that the Fatherland now awaits from its every son.” And we have already seen the how the “spirit of the fathers”, “awakening” in 1918, was declared to be the same spirit that motivated the Finnish fore-fathers in ages long past. “Our military service is like children’s play compared to what the Jägers had to endure”, a conscripted probationary officer wrote in a letter to the magazine in 1931, “– although both are motivated by the same purpose, the same feeling, the same trend of ideas, the same call.”

Self-restraint and the terrible moral dangers of military life

Less than a year and a half had passed since the end of his campaigns as a Jäger, when second lieutenant and theology graduate Hannes Anttila published an article in Suomen Sotilas in the early autumn of 1919. The story, entitled “The enemy lurking in the dark”, opened with an eerie story about a soldier volunteering for night reconnaissance into enemy territory. It is his first patrol service, and as the soldiers move into the dark night, the protagonist is struck by terror. After a short struggle with himself, he manages to overcome his fear. “… I dare not go back now. I am a soldier, a Finnish soldier. Come injury, come death! Forward I will go, until the mission is accomplished! (…) And you went. And you returned, returned as a man in the eyes of your relatives and your fatherland. You did not shun the danger, even if it terrified you. You fulfilled your duty, even if it felt heavy. And that is why you did a man’s work.” At this point, Anttila’s story makes a sudden jump to an evening leave in a garrison town in peacetime. There too, we are told, an enemy is lurking in the dark: “the sin of immorality” and its consequences, venereal disease. Even if the incautious soldier would be lucky enough to not catch an infection, he will certainly “desecrate his soul” if he does not turn back in time.

If you commit this sin, Anttila asks the reader, can you then look your mother, your sister, your wife or your fiancée in the eye with the same honesty as before? Anttila’s final appeal is written in the second person singular, addressing the reader like a priest in the pulpit addresses his congregation: “Are you, my reader, really so weak that you cannot restrain your own lusts? … Should you one day become the father of a family? Think what miserable creatures your children will be if you splurge the holy creative powers of your youth in the whirls of licentiousness … Mother Finland needs the stout arms of her every son to help her at this moment. Are you, my reader, a support and security to your fatherland or are you a burden and dead encumbrance? If you stray the city streets at nightfall with filthy thoughts in your mind, turn back, because that turning back is no shame to you but an honour! For he who conquers himself has won the greatest victory.” “The enemy lurking in the dark” wove together a religiously conservative view of what was moral behavior together with a number of different images: the courageous warrior, the son, the brother, the husband, the father and the patriotic citizen. An analogy was made between the warrior overcoming his fear before battle and the young man struggling to overcome his carnal desires. Honour and manliness demanded facing the two kinds of danger with equal courage, overcoming one’s instincts and emotions through willpower and a sense of duty.

Hannes Anttila and other “moralist” writers in Suomen Sotilas used a rhetorical technique associating unwanted behaviour with weakness and unmanliness, while the wished-for behaviour in conscripts was associated with image of the courageous warrior. They evidently did not think it would make a sufficient impression on the conscripts to tell them to behave in a certain manner because it was the “Christian” or “moral” thing to do. Instead, they tried to draw on the readers’ notions of manliness. They obviously thought that the threat of being labelled as weak in the eyes of their comrades would have a stronger effect on the rakes and lechers among the soldiers than just being branded as debauched. Perhaps they thought that “well-behaved” conscripts were best helped in the rough military environment if they were told that doing the morally right thing was also the mark of a true warrior. Such explicitly moralising storys, often but not always written by military priests, formed a significant subspecies among the rich variety of storys in Suomen Sotilas, especially during its first half-decade. Although these writings seldom referred explicitly to Christianity and religious decrees, they can nevertheless be associated with the trend of ‘muscular Christianity’ that arose towards the end of the nineteenth century in countries with an important cultural influence on Finland, such as England, Germany and Sweden. Muscular Christianity associated Christian morality was with strength and other stereotypical characteristics. This kind of rhetoric was also used by for example moral reformists in Finland opposing prostitution around the turn of the nineteenth century.

As we have seen, there were widespread moral concerns about the new military system in Finland, even in circles far removed from socialist antimilitarism. Drinking and sexual contacts with women in the garrison towns, behaviours which from a strictly military point of view were health hazards rather than anything else, were more profoundly worrying from a religious perspective, as were the rude language and indecent marching songs favoured not only by the rank-and-file but many officers as well. In Great Britain, Germany and Sweden, Christian revivalists founded recreation centres for soldiers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, an era of expanding mass armies and international armaments race, not least out of concern over the sinfulness spreading in the military training centres. The “old” Finnish Army’s magazine for soldiers in the Russian era, the bilingual Lukemisia Suomen Sotamiehille/Läsning för den Finske Soldaten (Readings for the Finnish Soldier, 1888–1902) contained writings depicting the barracks of the Finnish conscripted troops as places where innocent conscripts from the countryside were introduced to all kinds of vices. These moral concerns resurfaced when conscription was reintroduced in 1918-1919. For example, the dean of the military priests received a letter in 1921from the vicar of a rural congregation where worried parents had held a meeting to discuss the immoral influence of army life on their boys. Swearing, drinking, prostitutes roaming the garrison areas, and “the great dangers of immorality and the corruption of morals in bodily and spiritual respect” were mentioned in the letter.

The military priests, responsible for both the moral and civic education of the conscripts, shared the popular view of military life as potentially debauching conscripts. According to Regiment Pastor Verneri Louhivuori, ”that roughness which is characteristic to men” was multiplied in military life due to the absence of softening “counter-forces”. The military environment, he wrote, could become an ordeal for those who did not want to be brutalised. Jäger officer and theology student Kalervo Groundstroem warned of the “dangers of barracks life” in 1919. The military comradeship, which he himself in the previous article had celebrated as “a good educator”, could also be a breeding ground of “all things base and infamous”, Groundstroem wrote, hinting at soldiers’ contacts with prostitutes. The recruit, new to these surroundings, was especially susceptible to bad influences. These moralists evidently espoused the contemporary middle-class notions of morality.

The year spent in all-male company during the military service was supposed to make men out of boys and teach them to function as part of a group. Yet even in the army’s own magazine, the single-sex environment was at the same time seen as potentially detrimental to conscripts’s moral and ultimately their physical health – especially in a largely still rural country where country boys for the first time moved to live in a larger city, with all its temptations. In the voew of the “moralists,” the celebrated military comradeship could suddenly be seen in terms of a worrying tendency of conscripts to go with the crowd – a moral weakness that was contrasted to the lonely but champions of righteousness among the soldiers.

The Virtue of Self-Restraint

Towards the early 1930’s, the number of explicitly moralising writings diminished in Suomen Sotilas. Such storys were usually no longer published as editorials, but appeared in less prominent sections of the magazine, such as the Letters to the Editor pages. This could be an indication of sentiments calming down, as the conscript army slowly became established. Alternately, it could indicate a rhetorical shift where the older and somewhat condescending moral exhortations came to be understood as old-fashioned or counterproductive. What did not change in the “moral” agenda of Suomen Sotilas throughout the period, however, was the focus on the allegedly virtue of self-restraint. The emphasis on self-control is familiar from nineteenth century western bourgeois moralising. In Swedish nineteenth century self-improvement books for bourgeois youngsters and autobiographies by old bourgeois men, building astrong character was offered as the proper road towards manliness and the only way for a young man to avoid the pitfalls of his passions. Character, a vague term equivalent to moral principles in general, was in these moralizing works seen as a hidden potentiality in all men; part of the true individual and the effect of hard, enduring work. The “moralists” claimed that conscripts must withstand the passions and temptations of youth and build a strong character in order to become successful.

In the moral teachings of Suomen Sotilas, however, character, or the idea of having or striving for a permanent strength of will and morals, was not a central concept. Instead, morality and self-restraint were mostly discussed in terms of a continuous fight and struggle, a battle that a man must ceaselessly wage against immorality, both in the society around him and within himself. There does not seem to be a notion of this struggle having a terminus in a strong character achieved once and for all. The moral struggle is rather portrayed as a life-long condition. A useful citizen had to live his whole life fighting against “viciousness, drunkenness and the bestiality hidden in human nature”; without continuous moral struggle “the core of national life” would eventually be corrupted by immorality. The reason for this might be the strong connection of Suomen Sotilas to Christian theology. If Suomen Sotilas is compared with its nineteenth century predecessor, Lukemisia Suomen Sotamiehille, one can certainly see that Christian ideals such as submissiveness, humility and repentance, predominant in the older magazine, are played down. In the interwar period, moral virtue is recast in terms of will-power and self-restraint, reflecting an ideal soldier who is also an enfranchised citizen and thus more “adult” and autonomous in comparison to the ideal humble imperial subject of the nineteenth century. God and religion as the foundations of moral behaviour in the nineteenth century magazine are largely replaced with appeals to the readers’ patriotism in the 1920’s and 1930’s.

Nevertheless, through the prominence of military priests among the magazine’s writers, Christian religion still runs like a thin but everpresent thread through Suomen Sotilas. Religion intertwines with patriotism as the basis of the Finnish citizen-soldier’s morality and virtue. It is a defining difference between the righteous Finnish nation-in-arms and its adversary, the godless Bolsheviks. This strong presence of Christian ideals and influences is also one reason why the ideal images of Finnish soldiers in Suomen Sotilas almost never become aggressive, but retain a “softness” almost surprising for a military magazine from the heydays of Finnish nationalism. Throughout the period the images of soldering in Suomen Sotilas and its portrayal of the military retain an aura of moral purity and noble-mindedness that certainly served to camouflage the ugly realities of militarisation, military life and modern warfare. At the same time, these images and ideology were strikingly different from the contemporary fascist movements in Europe.

The Military as “Protectors of the Finnish Nation”

Military educators writing in Suomen Sotilas tried to construct an ideal image of the military centred on a sense of duty, a spirit of sacrifice, and self-restraint. An important element in all these constructions, hidden in expressions such as “every decent man” or “like our fathers before us”, was an imagined sameness and community among all Finns, who did “what a man had to do” and valorously defended their country. To the extent that this brotherhood-in-arms was made up of a special category of people, united around and through their shared membership of the military, the citizen-soldiers’ conceptualized themselves as a group within the Finnish people, the “Protectors of the Finnish Nation.” This conceptualization was a central piece of the military’s self-image. Firstly, a great part of the Finnish nation was deemed incapable of bearing arms and therefore in need of the soldiers’ protection: women, the old and the young. Secondly, there were those who threatened the Finnish nation from outside, namely the Russians and Bolsheviks. Thirdly, a heterogeneous group of Finnish men was deemed capable of bearing arms, yet for varying reasons failed to fulfil this duty and therefore threatened the nation from the inside.

The relationship between the conscript and those he was to protect was usually depicted in terms of the obligations of a good son towards his parents, sisters and younger siblings, not in terms of a father and husband protecting the members of his household. This was perhaps natural, as the intended readership, the conscripts, were only 20–22 years old. However, it gives a particular flavour to the relationship between the citizen-soldier and those it was his duty to protect and die for. In storys about the “fathers” and “fore-fathers” in Suomen Sotilas it is the mature man, master of his house and household, who goes to war. In storys directly addressing the readers as conscripts, however, they are spoken to as sons of either their physical parents or the abstract nation – “the Fatherland” or “Mother Finland” – who only pass over the threshold to real manhood by preparing to go to war. In relation to those incapable of bearing arms, the conscripted soldier does not fight and die to defend his property and his own patriarchal position, but to serve his family and his society. He is motivated but also bound by filial obedience, love and gratitude. He essentially sets out to defend a power structure that is not dominated by him and his comrades but by their fathers. In those rather few instances where individual fathers appear in the magazine, they are often stern, rebuking or commanding figures, such as the “father” quoted above writing an open letter to his “discontented son” in military service, telling him he must develop a sense of duty to become a man. This is a father figure in front of which the young conscripted man is supposed to be ashamed to show himself “soft”, complaining about treatment in the army and of withdrawing from his civic duty.

The images of mothers in Suomen Sotilas, however, are more ambiguous. Mothers are always depicted as loving their sons immensely. Mostly, this love is depicted as good, selfless and beautiful. The iconic mother is a moral educator and the ideal soldier is bound to her by love, gratitude and filial duty. He wants to protect her and he wants her to be proud of him. Drawing on this particular mother-son relationship, Finland as a nation is sometimes referred to as Suomi-äiti, Mother Finland, signalling that the relationship of the soldier to the nation should be that of a loving son to his mother. In some other instances, however, mothers are criticised for spoiling their sons by being too pampering or too dominant. Being a “mother’s boy” was presented as shameful for a man, and a great deal of the blame was directed at the mother. The border line was thus subtle and sometimes blurred between the good mother, who educated and motivated the citizen-soldier, and the bad mother, who detained her son in infancy, prevents him from stepping into manhood and thus reverses the relationship between protector and protected.

Women as girlfriends, fiancées or wives of soldiers rarely appear in Suomen Sotilas. The writers apparently did not expect the 21–22 year-old conscript to have a girlfriend, fiancée or wife waiting at home. Neither did they want him to think much about how soldiering related to his future relationships with women. In some fictional short stories a woman as a potential future lover and wife appears a motivating force for the soldier, spurring the hesitant soldier into battle, giving him a reason to resist the vices of garrison towns, or punishing the coward or traitor by refusing him her love. In general, however, the absence of female characters in the magazine’s pages is remarkable. It seems to underline the moral and religious beliefs of the writers for Suomen Sotilas, with the absence and exclusion of women from the writers perception of everyday life of conscripted soldiers in the garrisons reflecting what they wanted to believe, rather than what was more likely the reality of garrison life (soldiers being soldiers….).

Other than as mothers, women mostly appear in Suomen Sotilas as Lotta Svärd volunteers, working hard, bravely and patriotically for the common task of national defence with women’s chores: cooking, nursing and clothing the soldiers. These women were on the one hand active agents, but on the other hand confined to the feminine sphere of admiring and taking care of the military heroes. The image of female volunteers within the military system was certainly always positive; they were needed and useful and could be portrayed as courageous, even heroic in their own manner. Yet the division of labour was immovable, and the portrayal of women in Suomen Sotilas, as mothers, lovers or Lottas all conveyed the implicit message that armed defence and the fighting itself was the preserve of men. When there had been some letters to the editor of a Finnish newspaper in 1930 concerning conscription and military training for women, the editors of Suomen Sotilas only observed that the idea had been refuted by “many valid arguments”. They chose to comment on it themselves in the form of a photograph showing female members of the Russian Red Army among their male comrades, all looking relaxed and cheerful. “A repulsive sight”, the editors curtly noted.

Russians as Countertypes to Finns

“Countertypes” as a contrast to the Finnish ideal are a theme that runs through Suomen Sotilas through the 1920’s and 1930’s. Early countertypes were social outsiders such as Jews, Gypsies, vagrants, habitual criminals and the insane, all characterised by ugliness, restlessness, and a lack of self-control. A rather different kind of countertype emerges in nineteenth century self-help books for conscripts. There, un-men were not clearly demarcated social groups completely outside “normal” society, but gamblers and drunkards, ordinary men who had failed, made the wrong choices and therefore “fallen” into vice. These countertypes had a different functionality from “permanent outsiders”. The young man could not find easy self-assurance in feeling superior to the countertype, but was threatened by the possibility that he might become one of them if he did not heed the moralists’ advice. “Because men could fall, any middle-class man ran the risk of becoming that Other.”

The countertypes more commonly seen in Suomen Sotilas are the images of Russians, especially Russian Bolsheviks. In those instances where Russians were described in more detail it is obvious that they serve as a foil to Finnishness. A portrayal of Russian revolutionary soldiers stationed in Finland in 1917–1918 illustrates this: “Those loitering good-for-nothings slouching around in their down at heel boots and their stinking, dirty and shabby uniforms called themselves soldiers! Well, it certainly was the time of svaboda [freedom] – who would then care about such trivial things as washing his face or mending his trousers! (…) The outer appearance of those Russian squaddies was an excellent image of the confusion of their mental life (…).” These countertypes indirectly underline the importance of a Finnish soldier being clean and tidy, his outer appearance expressing a rational and virtuous mind; otherwise, he is no true Finnish soldier. Bolsheviks were portrayed as lazy and thievish people who shunned work and preferred confiscating goods from good thrifty people – marking the importance of honesty and industry in Finnish national character.

Two longer stories on the national character of the Russian people in 1932 explained that due to centuries of oppression by the Orthodox Church and the tsars, and in the absence of both individual freedom and religious and moral education, the Russians had developed into purely emotional beings, governed by impulses and temporary moods. A Russian could therefore at anytime contradict his own actions. He was unreliable, deceitful, completely unconcerned about lying and thieving, and lacked a sense of justice. Because he was a fatalist and did not think he could influence his own destiny or wellbeing, he lacked diligence and a sense of responsibility. He preferred talking to acting. He did not care about punctuality or efficiency. He treated a woman more like beast of draught than as his wife. As soldiers, Russians were intrepid but mentally slow, lacking in independence and perseverance. Finally, the author pointed to the eradication of the educated classes and the prohibition against religious education as the main obstacles for societal progress in Russia; “Without religion nothing lasting can be achieved!”

A Finnish soldier, one can derive from this description of the enemy, should be rational and always preserve his sang-froid; be principled and honest, treat women with respect, work hard and be the architect of his own fortune. He should also appreciate his individual freedom as well as the importance of Lutheran religious education and the leadership of the educated classes for Finland’s progress and prosperity. Due to the Russian’s weaknesses as soldiers, the Finnish Army could be victorious if its soldiers were quick-minded, self-propelled and persistent. On the whole, however, Russians were seldom described as individuals or as a people with certain characteristics. Russians in general and Russian Bolsheviks in particular were mostly referred to as an almost dehumanized force of evil, chaos and destruction, a threat against everything valuable in Finnish society and everything specific for the Finnish nation. Russia was “Asianness” threatening to destroy the entire Western culture. Russia meant “hunger for land, bestiality and deceit” and Bolshevism meant slavery as opposed to Finnish freedom. Russia was the Enemy, in an almost absolute sense.

Finnish Countertypes: the Dissolute and the Politically Deluded

Those Finnish men who were considered outsiders to the community of soldiers, consisted of the morally dissolute, the politically deluded, and the simpletons. Of these, only the morally dissolute can easily be labelled as countertypes. As we have seen, dissolute men were depicted as weak since they were incapable of self-restraint, e.g. in relation to alcohol, and lived “at the command of the whims, lusts and desires of the moment”. They were not free, but slaves to their passions and served to underline the virtues of moral purity, abstinence and self-control. Both physically and morally weakened by their vices, the morally dissolute as countertypes displayed how immorality destroyed the soldier’s fitness to fight and how true patriotism therefore demanded continence and clean living. On the whole, however, these countertypes are not very prominent in Suomen Sotilas, and where they appear they are seldom described in any graphic detail. If there was any concern over Finnish men degenerating into unmanliness and effeminacy through over-civilisation, similar to concerns in the large industrial nations before the Great War, it does not show in the pages of Suomen Sotilas. Given the very low degree of urbanisation and industrialisation in interwar Finland it is perhaps not surprising that military educators were not less concerned over the enfeeblement of their conscripts as over the relative strength and vigour of conscripts with the “wrong” political outlook.