By the mid-1920’s, Finland had begun to recover economically from WW1 and the cutting of off Russia as the major market. With this economic recovery came increased stability and the ongoing development of the military, as we have seen. The governments of both France and Britain had quickly become involved in the economic development of the Baltic littoral, and with Finland in particular. Many foreign businessmen, and sometimes even government officials, proved willing to go to extremes to win contracts, generally laboring under the assumption that an initial success would mean long-term rewards. As shown by the early French involvement with the Ilmavoimat, where there influence quickly faded, they were perhaps too optimistic. The Kirke Mission would demonstrate this.

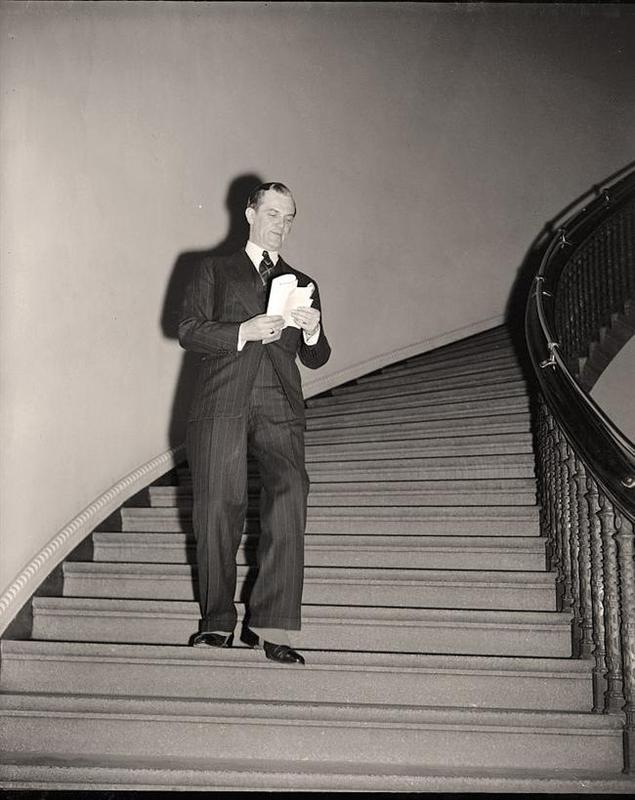

Over the early 1920’s, Great Britain had rapidly become Finland’s most important trading partner. Against Somervalo’s wishes, a group of British “experts” led by General Walter Kirke were invited to Finland by the Military High Command in 1924 to “help re-organize” the Ilmavoimat (Kirke himself was not an airman and had served in WW1 as a General Staff Officer at GHQ in France and Belgium). In 1918 Kirke had become the Deputy Director of Military Operations at the War Office and in this role he had been responsible for the preparation of number of papers and memorandum on various aspects of the RAF as well as with regard to the British Army.

Arms, Influence, and Coastal Defense: The British Military Mission to Finland, 1924-25

(taken from an article in the Baltic Security and Defence Review, Vol 12, Issue 1, 2010 by Donald Stoker – but note that the contents have been “tweaked” a little here and there in line with the ATL Scenario – but the tweaks are minor)

“Finland must take some chances, and history shows that it is safer to take chances with the Russian fleet than with the Russian Army.” – General Sir W. M. St. G. Kirke

In the modern period military missions have served as an important tool for nations pursuing military development, as well as those attempting to gain influence over the political and military policies of the recipient states. Typically, a smaller country contracts with a larger power for a visiting team of expert advisers. The dispatching power might have the best interests of the smaller state at heart, but self-interest usually drives both nations involved. In the decades between the world wars, the European powers generally sought to place military missions in foreign states to achieve economic benefits, particularly the sale of arms, or to counter the political and economic influence of a rival.

In 1924, as a part of its long-running efforts to draw-up an affordable naval bill to meet the nation’s defense needs, the Finnish government asked for a British military mission. The impetus for this came from the Finns in 1919, when Commodore G.T.G. von Schoultz discussed the idea with Marshal Mannerheim. Von Schoultz brought the idea before the government, but did not get what he wanted. Instead, the Finnish government chose a French military mission and then supplemented it with a short-lived French naval mission after World War I. The French presence would be temporary, but Finland’s quest for direct foreign military advice continued.The French, like the British, used military missions as a means of pursing several diplomatic, military, and economic goals. To Paris, they were an element of France’s Eastern European alliance and influence building strategy in the immediate post-World War I period. In February 1919, at George Clemenceau’s order, a mission comprising two Air Force and two Army officers, left for Finland.

To Mannerheim, the mission’s purpose was to instruct the army. But the French also had other tasks for it, some not unlike what the British would outline for their future mission. Its additional duties included intelligence gathering and conducting propaganda on France’s behalf. Similarly, the French dispatched missions to Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. The French hoped to tie these states to France’s post-World War I alliance strategy by having them adopt French arms and military methods, which was far more commitment than the British hoped to extract from Finland, or intended to give. The important economic advantages that it was hoped would result from such missions became increasingly important to London and Paris during the 1920s.

In late 1923, the Finnish government appointed a combined civilian and military committee to examine the state of the nation’s defenses. The proposals issuing from the group bore little relation to what the Finns could afford. For example, the amount the committee required for coast defense alone amounted to £5,000,000, a sum larger than Finland’s defense budget for two years. The proposal horrified civilian officials and worried officers of the army; the latter feared that their own requirements would be sacrificed for the needs of coast defense and indeed, sometimes this was the case. In 1923, the Finnish government had under consideration proposals to spend about 300,000,000 Finnish marks, nearly £2,000,000, on defense.

The government, citing the opinion of many Finns that the nation’s military officers lacked the necessary technical experience to carry out their duties, decided to seek military advice from abroad before submitting any military spending proposals to the Eduskunta. The Finns, at least initially, wanted a British commission that would advise on coastal, naval, and air defense, a group for which the Finns would pay all expenses. Finland also wanted the mission sent in as unobtrusive a manner as possible to avoid any unnecessary comments from the Finnish press. Approaching Britain for such advice was a new turn for Finnish policy. Previously, they had sought the services of France and Germany in such matters. Major-General Walter Mervyn St. George Kirke, who eventually led the British team, viewed the shift in Finnish policy as being thanks to the efforts of Sir Ernest Rennie, the British consul in Helsinki.

To the British government, the mission Kirke was to lead had two purposes: to counter French influence, and obtain orders for British armaments firms. The initial Finnish request for the mission came on 20 March 1924. The Finns wanted the mission purely for defensive reasons and had no aggressive intentions. Moreover, the Finnish government had a strong desire to get the best value for its modest funds. Finland wanted British experts to advise on the nation’s sea defense and the fortification of the Finnish coast, particularly in regard to coastal batteries, taking into consideration the materials then available. The Finns also wanted to know how air power could be used in coastal defense and whether or not aircraft could replace some of the units then being utilized to protect the nation’s maritime frontiers. The Foreign Office gave its blessing to the mission, though expressing some doubts as to whether or not it would ever materialize.

The War Office proposed a seven-member commission, one Chief of Mission, assisted by two men from each of the armed services. Lieutenant-Colonel F. P. Nosworthy, of the Royal Engineers, who was on a tour of the eastern Baltic and scheduled to be in Finland from 23-27 May, was instructed to obtain more information from Finland on its needs. The British government worried that the mission might arrive in Finland at a time of political crisis in the Finnish High Command, an allusion to infighting between the Jägers (the bloc of Finnish officers who had served in the German army during World War I) and their supporters, and the former Tsarist officers, and instructed Nosworthy to keep in close contact with the British representatives in Helsinki. The Admiralty also approved of sending British advisors to Finland—if the Finns agreed to pay all the expenses involved in such a venture.

Meanwhile, Commodore von Schoultz, the head of the Finnish Navy, met with Captain W. de M. Egerton, the British naval attaché in Helsinki, and discussed the possibility of a purely naval mission to Finland. The meeting provides insight into some of the problems within the Finnish high command. Von Schoultz was not aware that the Finnish government had requested a combined British military mission, or even that Finnish authorities had suggested it. Egerton believed that von Schoultz’s ignorance of Finnish policy resulted from the fact that the entire command structure lay in the hands of the Army.

Egerton wrote that “it appears to be their policy to keep the Navy as much as possible in the background.” Egerton also commented that the planned addition of a naval officer to Finland’s General Staff might result in better communication between the service arms. On 24 May 1924, Egerton, Nosworthy, and Major R. B. Goodden, the British military attaché for Finland and the Baltic States, met with Commodore von Schoultz, Commander Yrjö Roos of the Naval Staff, Major Martola of the Finnish General Staff, and a Finnish officer assigned to the Coastal Defense Artillery, Major Talvela. They discussed Britain’s dispatch of an expert commission to study various matters related to the coast defense of Finland. Finland wanted some type of mission, but several factors greatly concerned the Finnish government. Perpetually poor, it worried about the cost of the mission and because of this asked that it involve as few personnel as possible. The British were asked to suggest the composition of the mission, the rank and number of officers needed, as well as the mission’s duration. Commodore von Schoultz said that the coastal areas that they would be considering included parts of the Gulfs of Finland and Bothnia, as well as the northern and western shores of Lake Ladoga. The Finnish government reserved the right to designate which ports and bases required special defense preparations because of specific military or other reasons.

The Finns eventually decided that they wanted the mission to examine the defense of Finland’s entire frontier, both land and sea, including the Karelian Isthmus. However, it was only to consider land defense that “depended on naval actions, as e.g. bombardment of the coast, landing of armed forces with the purpose of surrounding field armies, or cutting off their communications, etc.” The northern parts of Finland, meaning the frontiers between Finland and Sweden, were not considered critical, a clear indication of who F inland saw as its potential enemy. The regions of vital importance included the areafrom Turku (Åbo) on the eastern end of the Gulf of Finland, and the northern and western coasts of Lake Ladoga. The Finnish authorities were to inform the commission of what locations they felt to have enough strategic and political significance to warrant fortification. The mission would be left to determine the best methods of defending these areas. After learning the breadth of the terms of reference for the mission, The British representatives agreed that they could not suggest a team smaller than ten members. They proposed that a mission led by a chairman whose rank and branch of service was determined by the British military authorities. He would be assisted by officers from the three branches of the British armed services: two from the Navy, two from the Army, and two from the Air Force. Two secretaries and one draftsman would also be needed, and it would take two months in Finland to fulfill the assignment. The Finnish Minister of Defense had had in mind a much smaller staff, perhaps two or three members, but von Schoultz agreed with the British estimate.

The officials also discussed the critical matter of expense. The British representatives estimated that the proposed mission would not cost more than £2,000 per month. They prepared an itemized salary estimate, which included a twelfth mission member, and a typist. The expected monthly cost was £1,035. The British expected the Finns to pay for travel expenses to and from Finland and to also make contributions to the pension funds of the participating officers during the time they spent in Finland. The British representatives then pointed out that if Finland spent the entire projected sum of £2,000,000, the cost of the commission as discussed would amount to only 0.1 per cent of the anticipated funds, a sum approximate to the cost of 12 modern sea mines. The British and the Finns both looked favorably upon the possibility of the mission. The French had a different attitude, or at least the British believed they did. Nosworthy reported that “French intrigue was very hot in Finland: they had somehow got to know all about our proposed Mission and were extremely annoyed about it.” Rennie informed Nosworthy that the French were “deeply disliked by the Finns” and mentioned that it was unlikely that the French would be “able to affect their [Finnish] decisions in any way.” Official notification of Finland’s desire for the mission came in early June 1924. The Finns agreed to the proposed composition, as well as to pay the salaries and travel expenses of the commission members. It was anticipated that the mission would last two months and that therefore the necessary personnel should arrive in Finland before the end of June. Hjalmar J. Procopé, the Finnish Minister for Foreign Affairs, was “anxious” for the dispatch of the experts. The Finns wanted them to study the defenses of the southern coast of Finland as well as Lake Ladoga, including both the inland and coastal defenses. The exact details of the work they would undertake would be settled after their arrival.

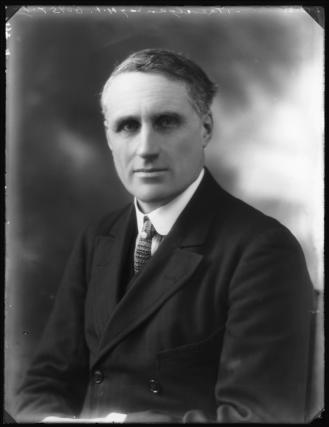

Hjalmar Johan Fredrik Procopé (born 9 August 1889 in Helsinki, died 8 March 1954) was a Finnish lawyer, politician and a diplomat from the Swedish People’s Party

Hjalmar Johan Fredrik Procopé (born 9 August 1889 in Helsinki, died 8 March 1954) was a Finnish lawyer, politician and a diplomat from the Swedish People’s Party who was elected to the parliament 1919-1922 and 1924-1926. He also worked in the Finnish embassy in Berlin from spring 1918 to the end of 1918. Procopé was a member Swedish People’s Party and served as a minister on several occasions: Minister of Trade and Industry from 1920-1921 in the Erich cabinet, Minister of Trade and Industry 1924 in the second Cajander cabinet, Minister of Foreign Affairs 1924-1925 in the second Ingman cabinet and Minister of Foreign Affairs 1927-1931 in four consecutive cabinets. Procopé returned to the Foreign Ministry as Finnish ambassador in Warsaw 1926. From 1931-1939 he served as the CEO of Finnish Paper Mills Association.

Over the war years of 1939-1944 he served as the ambassador in Washington. According to Kauko Rumpunen, a Finnish National Archives researcher, Franklin Roosevelt warned Procopé about the 28 August 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the contents that had been agreed between Nazi Germany and Soviet Union, including the secret protocols regarding Finland. Roosevelt’s warning was taken seriously, partly because Roosevelt hinted at the original source of the intelligence being a subordinate of Joachim von Ribbentrop, and resulted in additional urgency being given to Finland’s arms construction and purchasing programs. Procopé was largely responsible for urgently negotiating the thirty million US dollar loan granted to Finland in September 1939 which was used for arms acquisition immediately priot to the outbreak of the Winter War. Procopé also used the sympathy of Americans during the Winter War to benefit the interests of Finland and was a key figure in the preliminary negotiations which led to Finland entered the Second World War on the Allied side.

The shifting nature of exactly what the Finns wanted the British to do reveals much about the confused state of civil-military relations and defense planning in Finland. The Finns expressed some concern over the official name of the mission; they disliked the terms “Naval and Military Mission” and “Commission.” Procopé said that such terms “would give an air of permanency to the body of officers” that Britain sent to Finland and that it also might “give rise to undue comments” in both the Finnish and foreign press. The War Office recommended that a high-ranking Army officer serve as the mission’s head. The Foreign Office agreed, citing as the basis for their decision the more advanced state of development of the Finnish Army when compared to the Finnish Navy and Air Force. Others in the British government possessed little enthusiasm for the project. In January 1924, the first Labour Government took office. Ramsey MacDonald, the new Prime Minister, quickly granted de jure recognition to the Soviet Union, something other British governments had previously refused (though they would trade with them), and soon embarked upon efforts to strengthen Great Britain’s political and economic ties with Moscow. C. P. Trevelyan, the President of the Board of Education protested the timing chosen to send a “large military commission to teach Finland, one of Russia’s neighbors, how to arm themselves most effectively against her.” He also contended that this constituted a “definitely unfriendly act to the Russian Government and for that reason alone I suggest to the Cabinet that it ought to be stopped.” Trevelyan also reminded the British government of the criticism it had leveled at France for the manner “in which it had been arming and instructing in matters its various vassal nations in the East of Europe. It is most objectionable that we should begin to play the same game.” The Minister’s comments, especially his criticism of armament policy, though a bit alarmist, do demonstrate the minor shift in the foreign policy views of some government officials during the short-lived Labour government. Trevelyan’s outburst might also demonstrate the influence of the pacifist wing of the Labour Party.

Sir Charles Trevelyan, a member of the left-wing Fabian Society whose views were symptomatic of the British Left’s ongoing love-affair with Bolshevik/Communist totalitarianism

Sir Charles Trevelyan was a member of the British Liberal Party, born in 1870 and first elected to Parliament in 1899. He became a member of the left-wing Fabian Society and began to develop socialistic views on social reform. H. G. Wells kew him and was not impressed: he said “undoubtedly high-minded, Trevelyan had little sense of humour or irony, and was only marginally less self-satisfied and unendurably boring than his youngest brother, George.” He was opposed to Britain entered WW1 and resigned from the government in protest when was was declared, was one of the founders of the UDC – the Union of Democratic Control – the leading anti-war organisation on Britain. Trevelyan wrote articles for newspapers and gave a series of lectures on the need to negotiate a peace with Germany. As a result of this Trevelyan was attacked in the popular press as being a “pro-German, unpatriotic, scoundrel” and, like other anti-war MPs, was soundly defeated in the 1918 General Election. Trevelyan joined the Independent Labour Party and over the next couple of years he became a controversial figure with his attacks on the Versailles Treaty. In the 1922 General Election Trevelyan was elected to represent Newcastle Upon Tyne Central and when Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister in 1924, he appointed Trevelyan as his President of the Board of Education. His outburst against the mission to Finland was symptomatic of the British Left’s love-affair with Bolshevik/Communist totalitarianism and their role as “Useful Idiots.”

The Foreign Office considered the objections of the Board of Education unwarranted. Finland possessed only rudimentary defenses and the Foreign Office refused to believe that Finland, either with or without the temporary help of a commission of experts, could pose a serious menace to the Soviet Union. The Foreign Office also did not like having a British mission compared with a French one. They insisted, incorrectly, that similar projects undertaken by France tended to be larger and of a longer duration. Moreover, they contended, with far too broad of a generalization, that French officers serving with such missions generally held command positions within the forces for which they provided advice. In the case under discussion neither the Finns nor the British anticipated any long-term commitment; Britain was merely responding to a Finnish request. The diplomats insisted that the mission would continue despite the objections of the Board of Education—if the Army Council still agreed to the matter. The Council did, and hoped to dispatch the mission around 15 July 1924.

By 8 July 1924, the British had assembled the necessary personnel. Procopé and others in the Finnish government were pleased that the British had agreed to send the advisors, and happy with the terms concluded. Some also held the opinion that the British acted from an attitude of personal “disinterest,” a perception that the British hoped and tried to impress upon the Finns. To command the mission the British authorities selected Major-General Sir Walter Mervyn St. George Kirke, an officer of the Royal Artillery who had served in India and China, as well on the Western Front during the Great War. This proved a wise choice. General Kirke worked diligently and quickly, generally keeping the needs of the Finns in the forefront of any decision, an unusual attitude for French and British officials working in the eastern Baltic between the world wars. Aiding his endeavors were Captain Fraser and Commander Twigg, both of the Royal Navy, Lieutenant-Colonel Wighton, Army, Lieutenant-Colonel Ling, Royal Engineers, Group Captain Holt, Royal Air Force (RAF), Squadron Leader Maycock, RAF, two military clerks, and one military draftsman. The mission came to Finland about the middle of July 1924, an event kept very quiet. Neither the Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish forces, General Karl Frederik Wilkama, nor the Chief of Staff, General Oscar Enckell, received official word of the arrivals. Again, the communication problem within the Finnish military and civilian structures becomes apparent.

After meeting with the Minister of Defense, General Kirke realized that no substantial political or strategic groundwork existed upon which to base the suggestions of the British mission. The Minister of Defense could also provide Kirke with no real estimate on the amount of money available for the specific service branches. Kirke suggested a comprehensive survey of the entirety of Finland’s defense problems before embarking upon any expenditure. The Finnish government agreed and the advisors began their work on this basis. General Kirke wrote: “I thus found myself in the position of Minister of Defence having to allot tasks and funds as between the three Services, each of which naturally considered itself entitled to the Lion’s share.” Six weeks later, General Kirke and his officers had reconnoitered the country and filed a report detailing their recommendations regarding the navy, coastal defense, and the air force. The British experts cautioned that the needs of the army should be considered equally and expressed their view that the requirements of the ground forces were among the most urgent. The recommendations then went to the Revision Committee. They were adopted six months later after much argument. The government was “enchanté” with the mission’s progress statements and Kirke wrote that the group’s report would not only give the Finns better coastal defenses, but also save them several hundred million marks. Some in the leadership of the Navy and Coast Defense were not so pleased with the work of the mission, or its recommendations. The inspector of coast defenses protested the cuts in the funding estimates for his service from £5,000,000 to about £500,000. The head of the Navy also pressed the Revision Committee to adjust its expenditure proposals upward. The Air Force accepted the British advice and as funding became available it moved its development along the proposed lines.

Kirke’s handling of the mission bought much goodwill for Britain. At the beginning of his tenure in Finland, Kirke made it clear that he wished to complete his work as quickly as possible in order to pass on the financial savings to the Finnish government. He sent some of the mission personnel home within six weeks, earlier than expected. He also intended to return home before his allotted time. This, according to General Kirke, was a “novel” experience for the Finns. Previously, they had had a difficult time getting rid of earlier German and French advisors, and he insisted that the French mission had been particularly difficult to dislodge. Kirke believed, in typical British fashion, that the French “having found a soft job tried to stick to it as long as possible.” The remainder of the British personnel, except for Kirke and a staff officer, sailed on 11 September 1924. The various branches of the British government and military did not always assist Kirke’s endeavors to keep the mission’s costs at a minimum. The British military wanted the Finnish government to assume the expense of the salaries of the officers sent to Finland, an outlay that the armed forces would have borne in any circumstance. General Kirke asked his government to find ways to keep Finland’s costs to a minimum and requested that they not charge the Finns expenses that the government would normally bear. Kirke

had been anxious to keep costs low in an attempt to convince the Finns of the “disinterest” on the part of the British government, hoping, in turn, that this would result in orders for British industry, an attitude that clearly reveals Britain’s hope for the mission. Rennie, the British Consul, supported Kirke’s efforts and pointed out to his superiors (incorrectly) that the French only dispatch missions if contracts are placed in France, the result being the creation of a bad impression. Rennie insisted that minimizing the mission’s costs would bring benefits to British industry that far outweighed any additional expenses the government might incur. The Foreign Office agreed with Kirke and Rennie and asked the three service heads to do as the pair recommended. The Admiralty, at least, agreed. Kirke also attempted to have the cost of instruction fees lowered for Finnish air officers to receive training in Britain. The Treasury refused to allow a reduction in these charges for any foreign officers.

Kirke’s conscientious efforts to reduce the expenses of the mission paid extra dividends for British influence. The Finns were pleased and impressed with all of Kirke’s efforts, enough so that they asked the General to remain in Finland until the end of the year. The official reason given was that he would help in the reorganization of the Finnish Army. The Commander-in-Chief and the Chief of the General Staff also wanted Kirke to stay. Both had only recently taken up their appointments, the former commanders having been relieved from their positions shortly after the arrival of the British mission. Possibly, the deposed soldiers were victims of Finland’s purge of non-ethnic Finns from the ranks of the government and military. Kirke accepted the offer and returned to Britain in September to bring Lady Kirke to Helsinki. The couple arrived in Finland at the beginning of October, accompanied by Lieutenant-Colonel P.L.W. Powell. Powell came to meet Finland’s request for the loan of an army officer for six months, with the possibility of this period being extended.

The Finns gave Kirke a free hand and he anticipated completing his work by Christmas. He attempted to have the question of army reorganization transferred from the Revision Committee to the General Staff. Subsequent to Kirke’s appointment, the Committee had spent eight months debating what should be done in regard to the army, without reaching a conclusion. Kirke’s efforts proved futile and he contributed his failure to the Chief of the General Staff, who being “new to his post, was afraid of responsibility, and had not the experience necessary to enable him to assert himself.” The Revision Committee also did not want to relinquish their control because of their own desires to do the job. The Finnish government also preferred that the responsibility for defense recommendations remain in the hands of the Committee. Its members were drawn from many of the different parties of the Finnish political spectrum and the government wanted them to be directly responsible for the conclusions reached so that their respective political groups would be committed to finding the necessary funding. On strictly military matters, the Committee invariably accepted Kirke’s advice. Kirke did not like the slow pace of the Revision Committee and his hope of departing around Christmas proved futile. But, he wrote, that this “was natural, seeing that they were all busy men and many of them with little knowledge of the subject, though intensely anxious to do their best.” Other factors also added to the extension of his stay. Army officers responsible for preparing reports on the cost of various proposals had promised them by January. These had still not arrived by the time of the General’s departure at the end of March 1925. To hurry the Finns, General Kirke proposed coming home several times, once soon after Christmas 1924. He reported that this had “an instantaneous though temporary effect.”

The Kirke Mission’s Recommendations

In the end, what were the recommendations offered by General Kirke, particularly for the Finnish Navy and Coast Defense, and did the Finns implement them? First, Kirke believed that the Finns should quickly reorganize the military command structure, as one branch of the army frequently did not know what the other was doing. He suggested that the Finns use the British War Office as a model. The British also recommended the creation of a Finnish Navy as an independent service not tied to the coastal defense command structure. Kirke also thought that placing warships under the command of Army coast defense officers would hinder naval operations and fail to take advantage of what he saw as the “enterprising nature of the Finnish character.” He also argued against placing the Coast Defense forces under the command of the Navy. He recommended this because he felt that in the event of a successful invasion defensive operations would become primarily an Army show. Kirke also did not want the navy burdened with the problems entailed in coast defense. He believed that the navy needed to concentrate on its own development so as to emerge as an efficient force. To him, this was burden enough. To Kirke and his staff the naval forces of Finland had several objectives: 1) forcing the concentration of enemy units, which would hurt any efforts at blockade and make enemy ships susceptible to submarine attack; 2) attacking single enemy vessels; 3) launching naval attacks in combination with aircraft; 4) forcing the enemy to devote resources to convoying unarmed vessels – “in short, hamper his freedom of action on the seas.” To accomplish these tasks the British argued that Finland needed air and naval forces, but not at the expense of the Army. The Army was seen as the most important arm, and rightfully so. Aircraft were considered useful to the army, naval forces not as much so. Kirke did believe that the Finns needed some naval units and felt that they would utilize them effectively. He wrote that the Finns were “naturally a sea-faring people, possessing numerous small craft and the knowledge of how to use them, and an endeavour should be made to put these factors to good use.”

The British mission also filed exhaustive reports evaluating the extensive coastal fortifications that the Finns inherited from the Russians. Elements in the Finnish military wanted to arm most of these sites with the numerous artillery pieces acquired upon the collapse of the Tsarist regime. Kirke believed that making an effort to erect fixed defenses to protect the entire coast was not only impractical, but also unnecessary. Enacting such a plan would, in his opinion, result in a “useless diversion of funds” that could be better spent on the field army. It would also contribute to making Finnish defenses weak everywhere. Kirke argued for the installation of coastal batteries at strategic points along the coast in order to protect Finland’s ports and other important installations. Kirke also pushed for the standardization of the coastal defense weapons.

The Finns had a myriad of old Tsarist artillery, some of which had been purchased from American firms, ranging from light 47mm pieces to 12-inch guns. Kirke suggested that in the interest of efficiency the shore guns should be of three types: 75mm (these could also act as anti-aircraft guns), 6-inch, and 10-inch. The British mission also argued against the creation of an extensive network of coastal fortifications because of the amount of personnel that manning such installations required. The coast defense forces already suffered from a shortage of officers, and the expansion of this service’s duties would only exacerbate the problem. The construction of batteries at strategic sites would allow the concentration of scarce personnel. Kirke also recommended that most of the servicemen assigned to coastal defense duties be Suojeluskuntas members wherever possible. This would release additional men from the younger and more-fit classes for service in the regular army. This desire to prevent the dissipation of Finland’s manpower resources in order to provide the Finnish Army with sufficient cadres was one of the dominant elements that continuously influenced the recommendations that Kirke offered the Finns.

Kirke also believed that the Finns had inordinate fears regarding a Soviet amphibious assault and the shelling of Finnish cities by the Red Navy. He wrote: “Finland must take some chances, and history shows that it is safer to take chances with the Russian fleet than with the Russian Army.” He argued that Finland’s best defense against a Russian amphibious assault was the use of mobile reserves and aircraft. A railway runs along the southern coast of Finland and Kirke believed that the Finns would have no problems massing sufficient strength to throw back any Soviet invasion force that made it to shore through a gauntlet composed of coastal guns, the Finnish Navy, and the Finnish Air Force. Similarly, attacks launched across the ice during winter would also be very vulnerable to attacks from the air. Kirke also argued that the possibility of coastal bombardment on the part of Soviet warships would be at best slight, an assessment that the Winter War would later prove correct. The many islands that dot the coast of Finland force any bombarding warships to take up stations a great distance from the intended target. Before radar, this prevented accurate observation of the site under attack, except by the use of aircraft. Unless aircraft can stay over the target, the bombardment proves very ineffective. Coastal guns, which generally have greater accuracy than those on board ship, would also make getting too close to a Finnish port a dangerous proposition for a Soviet warship. These same islands also inhibit the movement of enemy warships along Finland’s shores. The confined waters force the vessels to operate singly or in small groups. These units would be very vulnerable to Finnish naval attacks.

The British also offered advice on the composition of the Finnish Navy. The main element would consist of three gunboats, or more accurately, armored coast defense ships. The British recommended 2,500-ton vessels with a shallow draft (12-14 feet), with 6-inch guns for the main armament. Kirke advocated three such vessels so as to always have one at sea. The British also arrived at this number because the best information that Great Britain then possessed on the Red Navy led Kirke to believe that at the most, the Soviets would only be able to have three destroyers on station at any one time. Additionally, if the Soviets armed their available merchantmen, they might be able to muster an additional three vessels. It was felt that the armored ship would be able to deal with any threat from enemy destroyers as well as protect coastal shipping. Kirke’s commission recommended that one armored ship be built immediately so that the lessons learned from its construction and use could be utilized in the building of its sister ships. The British plan foresaw at least three 400-ton submarines complementing the armored ships. Kirke recommended buying these abroad, preferably from Great Britain, in order to take advantage of British experience. British builders were more knowledgeable than those in any “available” nation. This would result in a larger expenditure for the submarines, but the Finns would reap the benefit of British experience. Kirke advised the construction of subsequent vessels in Finnish yards. Additionally, the Finns also had the old Russian submarine AG.16, which the Finns had raised and upon which they had already spent 19,000,000 Finnish marks for hull and machinery repairs. Because of its age and condition Kirke did not believe that the Finns should seek to make it an active part of their navy. As a complement to the submarines, the British recommended the purchase of a submarine parent ship.

During World War I Russian and British submarines operated from bases in Finland. The Russian submarines of the Holland type (AG 11, AG 12, AG 15 and AG 16) were scuttled in the harbor of Hanko on April 3, just prior to the German landing there. These submarines had good sea going qualities and were easy to handle. When the German troops advanced on Helsinki, the British submarine group sailed out and scuttled their submarines outside the city, on April 4, 1918. The Squadron consisted of the submarines E-1, E-8, E-9, E-19, C-26, C-27 and C-35. The British crews returned to Britain via Murmansk. AG 16 had been completed in 1916, commissioned on 21 July 1917 and was scuttled on 3 April 1918. Ag 16 was stored on land while repairs were made, but never completed due to the overall cost. In 1929 the AG16 was finally scrapped).

Kirke’s mission also advised the construction of barges that would be equipped with 12-inch cannon left in Finland by the Russians. Inspired by the British experience in the Dardanelles in 1915 and along the Flanders coast in 1917-18, these weapons were meant for defensive use against attacking enemy warships under the cover of Finland’s many islands. Kirke argued against the purchase of new Coastal Motor Boats (CMBs), believing that the money would be better spent on aircraft capable of carrying torpedoes, something that he believed, correctly, would become increasingly efficient in subsequent years. The British recommended that the Finns equip 50 vessels for minesweeping and that they purchase the paravanes necessary for this, as well as numerous extras. Defensive mine laying played a role in the British plans and included sowing the areas around Bjorkö, Vyborg, Vasa, and Kotka. A field would also be laid between the Åland Islands and Sweden in order to protect Finland’s communications. At the time of Kirke’s tenure, the Finns had 1,834 mines in storage. Kirke recommended the purchase of an additional 5,000 mines. In the end, the British concluded that the Finns should spend 423,914,340 Finnish marks over a six-year period for the improvement and expansion of their navy. This figure included money for personnel expenses, maintenance, and work on a number of bases, as well as the moving of one. The latest Finnish program drawn up for the navy and coast defense before Kirke’s arrival had called for the expenditure of 684,974,840 Finnish marks.

The Aftermath of the Kirke Mission

General Kirke left Helsinki on 24 March 1925. The Finns were very pleased by his work, especially his businesslike approach. They regretted his departure and offered their hopes that he would soon return. Kirke, as well as officials of the British government, believed the mission a complete success, and their comments on this subject demonstrate the primary purposes for dispatching the mission: influence and contracts. Kirke believed that the mission had produced an “invisible gain to British prestige” and that it had established good relations with the military leaders in Finland, particularly the Jäger officers, who had previously been perceived by the British as pro-German, and who were also the most important group in the Finnish military. In regard to the navy he wrote that “The extent to which British influence predominates will depend entirely on the extent to which the British Admiralty is prepared to help in training officers.” The Finns were particularly eager to send young officers to the United Kingdom for submarine training and Kirke wrote that “This is probably the only chance of getting any share for British yards in the work of the new Naval programme.” Kirke felt that relations between Finland and Britain would continue to improve steadily, the result being “good effects on commercial relations” between the two states. He proved overly optimistic. Despite his positive hopes for the future, Kirke was convinced that “the scales are heavily loaded against British firms.” He identified several obstacles, the first being the cost of French goods, which tended to be less than those from Great Britain. General Kirke also noted the French government’s policy of sometimes providing financial support to firms doing business with foreign countries, as well as the strong official encouragement from the French government. He also noted some additional past elements that weighed against the British: the French tactic of awarding medals to influential military and political personnel as well as “the propaganda of French officers who are practically agents for armament firms.” Finally, Finnish officers had often only seen French material.

General Kirke’s complaint regarding the French policy of awarding medals had particularly strong merit. During the 1920s, the French gave numerous Legions of Honor to important Finnish official, many of them naval officers. Included among these were Commander Einar-Wilhelm Schwank, 11 January 1923, and Commander Yrjö Roos, 23 July 1924, both of whom were future heads of the Finnish Navy. Important dignitaries receiving the medal included Dr. Rudolf Holsti, 22 April 1920, and Hjalmar Procopé, 22 November 1928. Commodore von Schoultz also held the Legion of Honor. But this did not win France the influence it desired. Despite the threat to the British from French competition, Kirke did not believe that the French represented the greatest danger. He saw the Italians and Swedes, both of whom had their advocates in Finland, as Britain’s most dangerous competitors. France, Italy, and Sweden had all accepted Finnish officers in to various military training schools and the Italians had even allowed the Finns to serve in command positions. But the real threat, which Kirke never realized, was Germany. Kirke’s presence and Finnish satisfaction with his activities and those of the other British officers did not prevent the Finns from also looking elsewhere for military advice. In early September 1924, near the end of the tenure of the British mission, Finland dispatched a group of leading Finnish naval officers to study the naval situations in Germany, Holland, and the Scandinavian countries. A British observer commented that Finland had “determined to have recourse to as many countries as may be for guidance in their task of reorganizing the defensive forces of their country.” During this same period, the Finnish Minister of Defense asked for permission to retain five foreign military experts for the new Army staff school scheduled to open on 3 November 1924. Included among these were one French, one Italian, and one Swedish officer.

Kirke’s intervention did prevent the appointment of a French advisor to the Finnish Air Force. Under an old agreement, General Enckell of the Finnish Army went to Paris sometime around Christmas 1924 to arrange for a French air officer as an instructor and air advisor to the Finnish government. Kirke, when he learned of this through the Finnish Air Force, pointed out to the Minister of Defense, as well as to the Foreign Minister, that simultaneously seeking the advice of two nations would be useless and “fatal to the efficiency of the Finnish Air Force, and that if they were definitely committed to the French, it would be best for us to go at once.” Rennie, the British Minister in Helsinki, supported Kirke’s view. A meeting of the Finnish Cabinet followed and its members voted unanimously that Kirke should stay and the French should be sent Finland’s regrets. Moreover, the Cabinet decided to request the services of a British air officer for two years. The British government agreed and Squadron Leader Field arrived in March 1925. In an effort to strengthen Britain’s economic chances, General Kirke advocated the granting of preferential treatment toward Finnish officers regarding invitations to British maneuvers. In Kirke’s view, the Finnish Army and government would greatly appreciate this and “it would probably lead to practical results when new equipment had to be purchased abroad.” Foreign Office officials had similar views. They believed that the appointment of a British air advisor indicated that the Finns were looking increasingly toward Britain. They also believed that if Finnish naval officers sent to Britain for training received a good welcome the “commercial results may very well be considerable.” A Foreign Office minute summed up in one sentence British hopes for General Kirke’s mission: “There is no doubt that the mission has enhanced our prestige & let us hope that commercial results will follow.”

The recommendations of the mission had a limited effect on the development of the Finnish Air Force, Army, and Navy, but little effect on the Coast Defense forces. In general, the British advice received a “harsh reception” from the naval officers. The mission’s recommendation that Finland remove many of the coastal defense guns was rejected. The Finnish high command could not understand why Kirke’s mission had made such a decision and refused to accept it. The Finns also disagreed with the British recommendations regarding the caliber of the guns for the planned coast defense ships; they believed the suggested British caliber insufficient for their needs. The Finns also did not like Kirke’s conclusion that CMBs were useless to Finland. The Finnish Navy considered them very necessary. Moreover, the torpedo boats, as well as the armored ships and submarines, were weapons that the Finns had the potential to construct, at least partially, in their own yards. This too was an important factor in their defense considerations, and correctly so. In the end, the impact of General Kirke’s mission in regard to the Navy and Coast Defense was minor and the Maritime Industrial Complex initiative that Mannerheim was instrumental in driving through superceded the Kirke Mission’s naval recommendations within a couple of years. But while the naval high command generally rejected the British proposals, the Army and the High Command took many of them to heart, overruling Somervalo’s opposition to many of the recommendations concerning the Air Force in doing so.

The Kirke Mission likely did succeed in changing Finnish attitudes toward Great Britain, therefore increasing British influence, and probably did soften the views of the Jägers toward the British. The French viewed it as a great success for their British opponent. Despite this, the British continually assumed, incorrectly, that the pro-German feelings of the Jägers equated to anti-British attitudes. This was in no way a correct assessment. The British cause was also dealt a severe blow by the resolution of the language dispute in Finland. In the early 1920s, many factions in Finland complained bitterly that many high political, military, and governmental positions were occupied by Finns of Swedish ancestry. This resulted in a campaign to remove many of the influential Swedish-speaking Finns from their jobs and replace them with Finnish speakers. The Swedish-speakers in the military also tended to be former Tsarist officers, another group that the more radical of the Jägers disliked. The Jägers played a key role in the campaign to remove these older officers and some of those who lost their positions were sympathetic to Great Britain and also the very men with whom the British were accustomed to dealing. Important among these was Commodore von Schoultz. Von Schoultz, the head of the Finnish Navy in the first half of the 1920s, was a former Tsarist officer and veteran of the Imperial Russian Navy. During World War I, he had served as a liaison officer with the British Grand Fleet. Present at the Battle of Jutland, Schoultz made comments on the fight in his memoirs that caused uproar in Great Britain (Von Schoultz G. Commodore: With the British Battle Fleet: Recollections of a Russian Naval Officer, London: Hutchinson 1st ed ND c1920). Schoultz criticized Admiral Sir John Jellicoe for breaking off the engagement in the evening, failing to take precautions to enable the British fleet to maintain contact with the enemy, and not sending his destroyers to launch night attacks against the Germans. Schoultz believed that these mistakes cost the British the opportunity to continue the battle the following day. Though many in Britain did not appreciate his remarks, Schoultz had maintained excellent relations with the British officers with whom he had served. The Commodore still had many friends in the Royal Navy and was generally well liked by British officials, no doubt his fluent English helped in this respect. Schoultz’s presence helped further the cause of good relations between Britain and Finland. Perhaps because of his German-appearing name, some French observers accused him of being a “germanophile.”

In Finland, in 1926, a law requiring knowledge of the Finnish language to hold a military post came into force. Officers were required to take a rigid language examination, which Commodore von Schoultz failed. The Commodore spoke excellent Russian, English, German, and French, but did not speak Finnish well enough to pass the exam. He was forced into retirement as were a number of other naval officers. A Finnish observer lamented Schoultz’s departure by writing that “there is nobody to take his place.” The Finns filled the recently vacated command posts with younger officers who would not normally have been awarded such senior slots. Commander Yrjö Roos moved into Commodore von Schoultz’s position in May 1925 when he was only thirty-five. Roos died in August 1926, his untimely death a result of a carbon monoxide leak in a minesweeper, the noxious fumes being accidentally pumped into the unfortunate officer’s cabin. Commander Achilles Sourander replaced Roos. In 1929, Commander Einar Schwank became the head of the Finnish Navy.

The retirement of von Schoultz cost the British one of their greatest allies. The Jäger victory in the linguistic struggle resulted in many of them filling positions of power that they had not formerly held. Though they were not necessarily pro-German, they were more inclined to deal with Germany than their predecessors. The Kirke Mission did produce an increase in British influence in Finland, but it was a short-lived bounty. Not long after Kirke’s mission, the Admiralty began to take the appointment of naval missions and naval advisors more seriously. The effects of the 1922 Washington naval treaties and lower governmental spending on ship construction began hurting Britain’s ability to produce the naval armaments that it needed. Obviously, in the eyes of the Admiralty this was an enormous security issue, and they began searching for ways to alleviate the problem. First, they tried granting subsidies for new construction, but by the mid-1920s it had become clear that this would not solve the problem. Soon, the Royal Navy saw Britain’s declining naval armaments industry as the greatest threat to British sea power, even more so than the Royal Navy’s true enemies: France, and most dangerous of all, the Treasury. The Admiralty began to see foreign orders as the solution. To protect its naval arms industry the Admiralty became very supportive of pursuing foreign orders. They believed that the best way to win them would be to send naval missions, naval advisors, and naval attachés, and even provide subsidies, to the potential customers. Moreover, naval missions could counter French influence, and the Admiralty’s agreement to send a mission to Romania was partially motivated by a desire to keep the French from sending one. Also, Romania, like the Baltic States, was seen a portal to Russian trade. This was a clear reversal of the 1919 Royal Navy policy against the dispatch of missions. The worsening economic conditions of the interwar period would force even more changes in Admiralty policy.

Later, in a lecture delivered after his return to Britain, General Kirke stressed his confidence in the Finns ability to defend themselves against the Soviets, stating that “one may reasonably conclude that the defence of Finland’s coasts and essential sea communications is by no means an impossible, nor even a very difficult task.” The results of the Winter War would prove him correct. The Finns did do some of the things that the British recommended, starting with the acquisition of a number of submarines. But this would not be done with British help. German experts, the most important of whom was a former submarine officer named Karl Bartenbach, were already quietly working in Finland. Puppet German firms built vessels for the Finnish Navy in Finnish yards, laying the foundation for a modern Finnish Navy, and incidentally, Nazi Germany’s U-boat arm.

But rather than the three coastal defence ships the Kirke Mission had recommended, they then concentrated on building a destroyer flotilla based on the Polish Grom-class design, together with a flotilla of smaller Anti-Submarine Corvette’s based on a simplified Swedish Goteborg-class design. They also went ahead, against the British recommendations, and built a sizable torpedoe boat flotilla in the last half of the 1930’s. The British sent the Kirke Mission to keep Finland from the camp of French influence and to win sales for British firms. London should have been worrying about the Germans, Poles and Swedes.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

2 Responses to The Ilmavoimat and the Kirke Mission