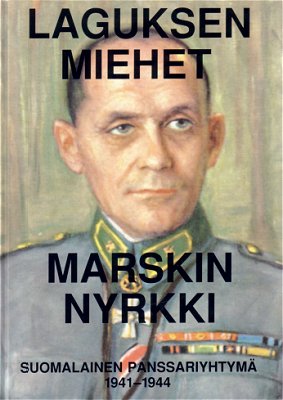

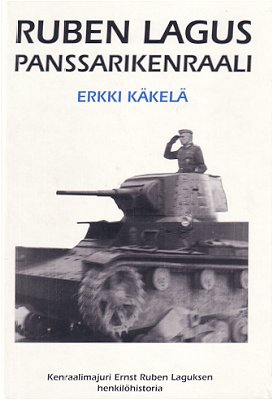

On the 31st of November 1939, when the Red Army launched its attack on Finland, one Finnish Panssaridivisoona (the 21st, nicknamed “Marskin Nyrkki” – The Marshal’s Fist), an armoured division commanded by Kenraalimajuri Ernst Ruben Lagus) was in existence. There were also three Erillinen Pansaaripataljoona (Separate Tank/Panzer Battalions equipped with a miscellaneous collection of tanks) who formed part of the Finnish Army’s “Suojajoukot” Brigades facing the first onslaught along the Border.

By the end of the fighting over the winter of 1939/1940, a second Armoured Division, the 22nd (somewhat derivatively nicknamed “Marskin Saapas” – The Marshal’s Boot – unofficial motto “when they’re down on the ground, put the boot in”, commanded by Kenraalimajuri Hans Kalm) had been formed and equipped entirely with captured Soviet tanks, artillery and vehicles. By the end of the Winter War, the 22nd had already won a reputation as perhaps the most aggressive and ruthless fighting division in the Finnish Army, an honor due in no small part due to their divisional commander. There were also the three Separate Panssaripataljoona, the Polish xxx Armoured Brigade and a number of mechanized Jaeger, Artillery, Pioneeri and other combat and combat support units, who by the end of the war had been formed into the rather more ad-hoc 23rd Panssaridivisioona (“Marskin Vasara – The Marshal’s Hammer”). Despite losses in battle, the Finnish Army would end the Winter War in late 1940 with three Armoured Divisions, a wealth of combat experience and developments in tactical doctrine which placed them squarely on the leading edge of Combined Arms Warfare for the remainder of WW2. Following the Winter War, these three Armoured Divisions would over time re-equip themselves with the newer model tanks and armoured fighting vehicles rolling off the Patria production line in Tornio, later augmented by lend-lease equipment supplied by the US and tanks and artillery somewhat reluctantly provided by the USSR (in return for raw materials such as nickel, copper and steel). Such was the Finnish skill in Armoured Warfare (“Ukkossota” or “Thunder War” as it came to be referred to in Finnish milspeak) that the Allied commanders and senior officers of the British Commonwealth, US and Polish armoured units who fought alongside the Finnish Army and under overall Finnish command against Germany over 1944 and 1945 would become the leading exponents of this form of warfare in the West through the early post-war decades.

At the time of the outbreak of the Winter War, the fact that Finland possessed even a single Armoured Division and three additional armoured battalions meant that she was a major armoured power. Finnish Panssaridivisoona Officers also had considerable practical experience garnered from the use of armour by the Finnish Volunteer brigade, Pohjan Pohjat, in the Spanish Civil War (where a Panzer Battalion fough to great effect as part of the brigade). The evaluation of this experience and the development of armoured and combined arms expertise in battle over the years 1937-39 in Spain had allowed the Finns to acquire unequaled experience and to develop and evolve their tactics in the crucible of battle. When the Finnish Armoured units came to join battle with the Red Army, the Finnish Army’s combined arms battle doctrine was based on an unrivalled familiarity with tank combat and combined arms warfare that exceeded even that of the Germans and the Russians (keeping in mind also that most of the Russian “experts” in armoured warfare, as well as those Russian Advisors with experience in Spain had been ruthlessly purged by Stalin). Moreover, the Germans had gone into Spain to assist the Nationalists with no real objective defined as to the use of Spain as a testing ground for weapons and tactics. As it turned out, new weapons (tanks and aircraft) were used in combat and lessons learnt, but this was not the original intention and any such lessons learnt were more byproducts of th aid to the Nationalists rather than a deliberately planned outcome. By contrast, the Finnish volunteers had gone into Spain with the expressed objective of testing, refining and correcting their doctrine and tactics, an objective that remained at the forefront of Pohjan Pohjat’s mission for three long years of combat. The lessons learnt were rapidly absorbed, with corrections and improvements to doctrine and tactics reviewed, decided on, and made at a rapid pace and in an ongoing cycle of experimentation and evaluation.

The Finnish Army also ensured that a considerable number of suitable “volunteers”, most of them NCO’s or officers, were rotated through Pohjan Pohjat, gaining valuable combat experience. These “volunteers” would subjected to rapid and intensive training both before their departure to Spain and on arrival, prior to entering combat. They would also experience accelerated promotion and preference for advanced training within the Reserves on their return, meaning that when the Winter War came, a considerable number of unit commanders and senior NCO’s were “battle-hardened” soldiers with experience commanding in the storm and smoke of combat. Likewise, those ordinary soldiers who fought in Spain as volunteers could be assured of immediate promotion into the ranks of the junior NCO’s on their return, again with preference for further training and promotion. Many of these NCO’s would train Finnish Army conscripts through the years 1938 and 1939, passing on hard-learnt lessons to their students.

And with a full overstrength brigade of volunteers in Spain, some 6,000 men at any one time, by the end of the Civil War some 20,000 men had rotated through Spain. This gave the Finnish Army a considerable nucleus of men with actual battle experience – and these men were sprinkled throughout every unit in the Army. The establishment and maintenance of single Panzer Battalion using a mix of captured Russian tanks, a small number of German tanks and some supplied by the Italians enabled the nacent Finnish Panssari units to also experiment, develop and turn into tactical doctrine their experiences in armoured warfare over the three years of constant fighting. Pohjan pohjat were in some ways a unique volunteer unit in Spain. Where Franco wanted the Italians as a source of weapons, he was not overly enamoured of Mussolini’s attempts to turn Spain into a protégé of the Italians and he many times frustrated the Italian commanders in Spain. He was also unimpressed by the fighting abilities of the Italians units in Spain. Similarly, Franco welcomed Germans arms and aircraft, but was well aware of the Germans intentions in Spain and deeply resented their at times extortionate demands for payment.

Franco himself was also playing the various political groupings within the Nationalist fold – in particular the Falangists and the Carlists. Himself neither a fascist nor a monarchist but rather a Catholic nationalist, Franco had no intention of allowing either movement to gain the ascendancy within Spain, preferring to reserve that role for himself. While not overly enthusiastic about foreigners fighting in Spain, Franco was rather less reserved about Pohjan pohjat. Brought to Spain under the aegis of the Italians, the Finns quickly negotiated their way into an attachment with the Spanish Foreign Legion where they soon established a reputation as skilled and ruthless soldiers, willing and able to take the battle to the enemy whilst eschewing the publicity and the glory that the Italians demanded. In this, the possession of their own tanks, artillery and other specialized units as well as attached air units made them very much a prototype combined arms unit capable of fighting independently and with a great deal of firepower at their disposal. They would also pull the Italian’s bacon from the fire on more than one occasion, first and perhaps most notably in the Battle of Guadalajara (March 8–23, 1937).

Pohjan pohjat and the Battle of Guadalajara

After the collapse of the third offensive on Madrid, Spanish Nationalist General Francisco Franco decided to continue with a fourth offensive aimed at closing the pincer around the capital. The Nationalist forces, although victorious at Jarama River, were exhausted and could not create the necessary momentum to carry the operation through. However, the Italians were optimistic after the capture of Málaga, and it was thought that the Italian forces could score an easy victory owing to the heavy losses sustained by the Republican army during the Battle of the Jarama River. Italian dictator Benito Mussolini endorsed the operation and committed the Italian units to it. The Italian commander, General Mario Roatta, planned for his forces to attack Madrid from the north-west. After joining the Spanish Nationalist corps “Madrid” on the Jarama River, they would begin the assault on Madrid with the Italians executing the main attack. The Spanish “Soria” Division was present to secure the operation, but played no part in the first five days of fighting. The main attack began in the 25 km-wide pass at Guadalajara-Alcalá de Henares. This region was well suited for an advance, as there were five good roads running through it. Three other roads in the area led to Guadalajara, allowing for the possibility of capturing this town as well.

The Nationalist forces were made up of 35,000 soldiers, 222 artillery guns, 108 L3/33 tankettes and L3/35 tankettes, 32 armoured cars, 3,685 cars, and 60 Fiat CR.32 fighter planes. The Republican presence in the Guadalajara region consisted only of the 12th Division of the Spanish Popular Army under Colonel Lacalle. He had under his command 10,000 soldiers with only 5,900 rifles, 85 machine guns, and 15 cannon. One company of T-26 light tanks had also been sent to the area. No defensive works had been constructed in the Guadalajara region as it was regarded as a peaceful part of the front. The Republican Army staff was convinced that the next Fascist offensive would come from the south. On 8th March 1937 the Italians began their attack, breaking through the Republican line and advancing between 10 and 12 kms before slowing down due to reduced visibility from fog and sleet. Falling back, the Republican commander requested infantry reinforcements and the company of tanks. On March 9th the Italians resumed their assault on Republican positions, advancing a further 15 to 18 kms but were again bogged down by poor performance and low visibility before being halted by battalions of the republican forces XI International Brigade. By the end of the day, further Republican reinforcements began to arrive, with additional units also arriving the next day.

On the morning of March 10th, Italian forces launched heavy artillery and air bombardments and renewed the assault, capturing the towns Miralrio and Brihuega (the latter without resistance). Italian assaults on the positions of the XI and XII International Brigades continued throughout the afternoon, still without success. The following day, the 11th, the Italians began a successful advance on the positions of the XI and XII International Brigades, who were forced to retreat before managing to halt the Italian vanguard some 3 km before the town of Torija. The Spanish Nationalist “Soria” division “Soria” also advanced, capturing the towns of Hita and Torre del Burgo. On March 12 the Republican forces launched a counterattack. Close to one-hundred ‘”Chato” and “Rata fighter planes and two squadrons of Katiuska bombers of the Spanish Republican Air Force were used, while the aircraft of the Italian Legionary Air Force were grounded on water-logged airports. After an air bombardment of the Italian positions, the Republican infantry supported by T-26 and BT-5 light tanks attacked the Italian lines. Several Italian tankettes were lost when General Roatta attempted to change the position of his motorized units in the muddy terrain; many got stuck and were easy target for strafing fighters. The Republican advance reached Trijueque while an Italian counterattack regained no lost terrain.

At Guadalajara, Pohjan Pohjat fought that most difficult of battles – withdrawing and fighting a delaying action whilst under continuous heavy attack…

On March 13 the Republicans counterattacked at Trijueque, Casa del Cabo and Palacio de Ibarra was launched with some success, with the 14th Division crossing the Tajuña River to attack Brihuega. The Italians had been warned that this might happen, but ignored advice from the commander of the Finnish Volunteer Brigade attached to their forces for the operation, Colonel Hans Kalm. Between March 14-17 the Republicans redeployed and concentrated their forces while their air force units continued to attack the Nationalist forces. On March 18 the Republicans resumed the attack, crossing the Tajuña River and nearly managing to surround Brihuega, causing the Italians to retreat in panic. The Republican advance was only slowed by the Italian Littorio Division, arguably the best of the Italian units. An Italian counterattack on Republican positions failed and it was only the Littorio Division that saved the Italians from a complete disaster when they conducted a well-organized retreat. What of course is more or less unknown is that the Italian commander, General Roatta, had requested the attachment of the Finnish Volunteer Brigade to the Littorio Division for the offensive.

Colonel Hans Kalm, CO of Pohjan Pohjat. His fighting withdrawal at Guadalajara was a classic example of this type of battle

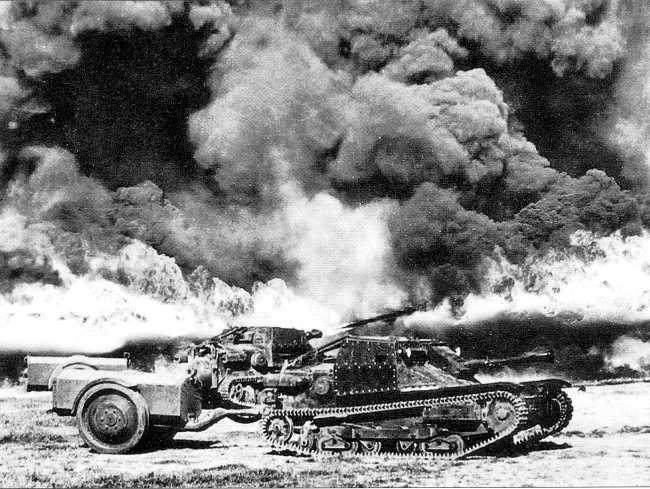

The Finns had arrived late through no fault of their own and had played no part in the earlier fighting. However, as the Italian units withdrew in panic, Colonel Kalm moved Pohjan Pohat forward on the morning of March 19th in a sudden tactical counter-attack that hammered into the advancing Republicans, with troop and tank movements well-coordinated with artillery support and close air support. Outnumbered and constantly in danger of being outflanked, Pohjan pohjat under Colonel Kalm fought the Republicans almost alone, conducting a skilfull fighting withdrawal in the face of vastly superior forces. In the process, Pohjan pohjat also augmented their equipment with abandoned Italian tanks, tankettes and guns. Over March 19th and 20th, Pohjan pohjat would fight almost alone, covering the rapidly retreating Italians and using their 76mm Bofors AA guns to shred attacks by Republican tank units – a use of the Bofors 76mm which would have far-reaching implications as the success of the weapon in an anti-tank role, even without anti-tank ammunition, was digested. Well-coordinated artillery fire was used to break up Republican infantry attacks, as well as to separate attacking infantry from the tanks, while aerial reconnaisance and close air support was used continuously. On the nights of March 19th and 20th, Pohjan pohjat would launch night attacks on the Republicans, keeping them in a constant state of tension. By the 21st, units of the Littorio Division would begin to coalesce around Pohjan pohjat but the Republican counter-offensive would not be halted until the Valdearenas–Ledanca–Hontanares line was reached, and only then because Franco had sent reserve formations to this line of defence. Nevertheless, Pohjan pohjat had played an important part in slowing the Republican advance.

The Battle of Guadalajara was the last major victory of the Republican Army and did much to lift Republican morale. Herbert Matthews claimed in the New York Times that Guadalajara was “to Fascism what the defeat at Bailén had been to Napoleon.” The British press heaped scorn on this “new Caporetto”—alluding to a great Italian defeat in the First World War – while former British Prime Minister David Lloyd George wrote mockingly of the “Italian skedaddle,” infuriating Mussolini.

The Italians lost some 6,000 men and a considerable number of light tanks and planes (Pohjan pohjat by their own count picked up from the Italians 35 artillery pieces, 85 machine guns, and 67 abandoned Italian tanks (from which a 2nd Panssari Battalion was formed), none of which were returned). Above all, Guadalajara was a severe blow to Italian morale and caused a major loss of prestige for Italy’s fascist regime, whose Duce had orchestrated the deployment of the Italian army in the hopes of stunning the world with a show of Italy’s “iron military strength. If Republican confidence soared, there was no corresponding loss of morale in Nationalist circles, which regarded the Italian expeditionary force with some contempt. German officers in Salamanca sneered that even “Jews” and “Communists” (the International Brigades) could beat the Italians.

Many Spanish Nationalist officers, resenting Mussolini’s henchmen for carrying their own personal war into Spain, were amused to see their boasting and well-equipped allies, so full of bluster before entering battle, brought so low at the hands of what they saw as fellow Spaniards, even enemy Spaniards. Franco’s soldiers began singing popular Italian tunes with the wording changed to mock the defeated Italians. The following chorus, originating with General Moscardó’s Navarrese, humorously takes the Italians to task for their earlier complaints about the lack of motorized transport in the Nationalist ranks:

Guadalajara no es Abisinia (Guadalajara is not Abyssinia

Los españoles, aunque rojos, son valientes, (Spaniards, even if Red, are brave)

Menos camiones y más cojones ((You need) fewer trucks and more balls)

Contrastingly, the Finns came out of the battle with their reputation solidly enhanced. The Spanish were well aware of the part Pohjan pohjat had played in covering the panic-stricken Italian withdrawal and their attached Spanish liason officers had sung the praises of the Finnish volunteers as they launched a series of devastating counter attacks as they conducted their fighting withdrawal. Months later, Franco would personally decorate Colonel Hans Kalm for his command in this battle. The Italians for their part were also somewhat grateful to the Finns for turning what could have been a devastating defeat into “merely” a major embarrassment. The Finns for there part were not all all eager for publicity and with the Nationalist control of the news media being what it was, no reports of the Finnish action found their way into the media. The Littorio Division were given the credit for slowing the Republican advance (in which they did in fact play an increasing part over the last 3 days of the Republican counter-offensive) and this is how history has recorded the battle.

For their part, Pohjan pohjat had fought a large battle in circumstances somewhat similar to those they could expect to face in any war against Russia. This was an invaluable experience and the Finns would draw somewhat different conclusions from other observers as to the significance of the battle. For outside observers, largely unaware of Pohjan pohjat’s involvement, the tactical lessons of the battle were ambiguous and prone to misinterpretation. The failure of the Italian offensive demonstrated the vulnerability of massed armoured advances in unfavourable terrain and against a coherent infantry defence. The French General Staff, in harmony with existing beliefs in the French Army, concluded that mechanized troops were not the decisive element of modern warfare and continued to shape their military doctrine accordingly. A notable exception to this view was Charles de Gaulle. The Germans (and the Finns, it must be added) escaped this conclusion by correctly dismissing the Guadalajara failure as the product of Italian incompetence.

For their part, Pohjan pohjat had fought a large battle in circumstances somewhat similar to those they could expect to face in any war against Russia. Here, a Red soldier attacking a temporary Finnish defensive position…

In truth, both views had some merit: armoured forces were largely ineffective against prepared defences organized in depth; in adverse weather, and without proper air support, the result was disaster (Italian strategists failed to consider these variables). The German assessment correctly noted the deficiencies in Italian soldiery, planning, and organization that contributed to their rout at Guadalajara. In particular, their vehicles and tanks had lacked the technical quality and their leaders the determination necessary to effect the violent breakthroughs characteristic of later German blitzkrieg tactics.

Soldiers of Pohjan pohjat move an artillery piece in Spain as they prepare to fall back. Battle of Guadalajara

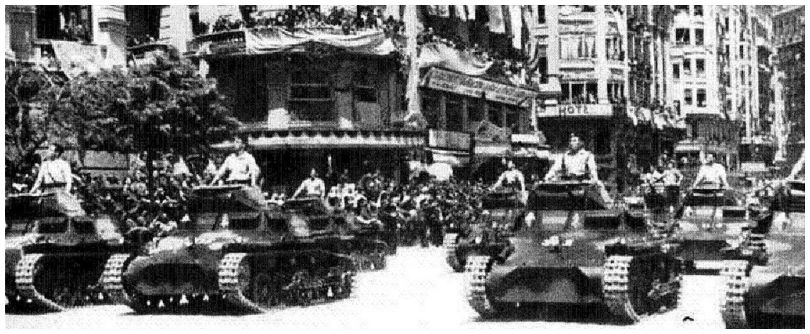

Tanks of Pohjan pohjat’s Panssaripataljoona participate in the Nationalist Victory parade, Madrid, 1939

Returning now to Finnish Armoured development

By way of contrasting various Armoured unit strengths, at this time in late 1939 Britain had one active armoured division, with two more only in the process if being formed, together with two independent armoured brigades. France had two mechanized cavalry divisions. Italy had three armoured divisions (Ariete, Centauro & Littorio). Germany had six armoured divisions, three of which were organized over 1938-39 (until October 1938, the Czechs had had a considerable armoured force, but the Czech tanks had been absorbed into the German Army and indeed, would form a major part of German armoured strength in the attacks on Poland, on France and later on the Soviet Union). The United States had one mechanized cavalry brigade. The Soviet Union had as many as twenty one armoured brigades, organized into seven mechanized corps (but no divisions). Of all of these countries, only Germany had developed mobile combined arms warfare to any degree, and even in this the Finnish doctrine and tactics had evolved rather further.

The image of the Red Army that Stalin liked to portray to the world – a modern, fully mechanized force. These T-38 light amphibious tanks and T-26 light tanks parading in Red Square in 1938 look impressive.

Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky was charged at his trial with taking part in a “right-wing-Trotskyist” conspiracy in which he collaborated with the Germans against the Soviet Union. Tukhachevsky and Kliment Voroshilov, the People’s Commissar for Defense, had nothing but contempt for each other.

Simon Sebag Montefiore, who has conducted extensive research in Soviet archives, states however: “Stalin needed neither Nazi disinformation nor mysterious Okhrana files to persuade him to destroy Tukhachevsky. After all, he had played with the idea as early as 1930, three years before Hitler took power. Furthermore, Stalin and his cronies were convinced that officers were to be distrusted and physically exterminated at the slightest suspicion. He reminisced to Voroshilov, in an undated note, about the officers arrested in the summer of 1918. ‘These officers,’ he said, ‘we wanted to shoot en masse.’ Nothing had changed.”

EFIMOV, BORIS. EZHOV’S IRON GLOVE. POLITICAL CARTOON, 1937: This propaganda cartoon shows Nikolai Yezhov, leader of the NKVD secret police and Prime executor of the purge under Stalin’s directives, crushing the traitors who are portrayed as snakes.

The Finnish Armour Development program and the concurrent development of armoured / combined arms doctrine was no accident. The landmark 1931 Military Review which set out Finnish Defence plans for the upcoming decade (and which was updated annually) had outlined the need for an ongoing evaluation of many different aspects of modern warfare, not least of which was a thorough examination of the impact of that radical new weapon, the tank, on warfare and on the Army. The immediate result had been the setting up of the Combined Arms Experimental Combat Unit in 1932 and the 1933 Tank Evaluation Program (which would turn into an ongoing examination of armoured warfare in other militaries and on equipment and weapons available).

Into these two years, the Finnish Military compressed a detailed and through analysis of the experiences of World War One together with technical developments that had occurred through the 1920’s. The result was a study entitled “Modern Combined Arms Formations 1933 (Provisional)”. Packed into its 138 pages was a volume of accurate and farsighted analysis – in hindsight, where this study deviated from what was to happen, it was very seldom far wrong. “Tank brigades depend on speed and firepower to overcome the defence. Open and undulating ground is therefore more favorable to them, since it presents few obstacles to tank movement and offers little cover to anti-tank weapons.” On the other hand “Enclosed country is favorable to infantry action. In this type of country the machineguns of the defence are hampered, and opportunities thus occur for infiltration by infantry in co-operation with armoured machine-gun carriers and armoured mortar carriers.“

Anti-tank defence should be the work of a 37mm gun and contact mines (“one Ford Muuli can carry 250 anti-tank mines” and “large numbers of anti-tank mines mixed with anti-personnel mines can be utilized to rapidly form defensive barriers which can then be defended by anti-tank guns, machine-guns and mortars“) and “anti-tank defence may also be given to 76mm anti-aircraft guns which are quite efficient for the purpose” (practical experience in Spain reinforced this particular comment). Mention is also made that infantry battalions should be equipped as a matter of course with the 81mm Mortar and with 37mm anti-tank guns. The small study is full of such gems, including a remarkably clairvoyant analysis of the uses of air power in the ground attack role (with mention made of the Ilamvoimat’s now antiquated WW1-era Junkers J1 ground-attack aircraft and the way in which these were used in combined-arms operations by the German Army in WW1 as well as on RAF ground attack capabilities in WW1). In its analysis and its conclusions, this small and concise study is well ahead of anything else that had been written on the subject other than a similar and rather more obscure study completed for the British War Office in 1931 and authored by Colonel Charles Broad (who, interestingly, together with a British Army Captain, Basil Liddell Hart, are listed among the sources of information for the Finnish Study).

“Anti-tank defence should be the work of a 37mm gun and contact mines” – Pohjan pohjat volunteers in Spain found the Finnish-manufactured Bofors PstK/36 37mm anti-tank gun to be an effective weapon…

The Finnish Army would go on to take almost all of the recommendations of this study and trial them in their Combined Arms Experiemental Unit and in ongoing exercises. The results of this hothouse of innovation and of trial and error would rapidly percolate outwards into the wider Finnish Army and Air Force over the following years. The Combined Arms Experimental Unit would also provide the “Enemy Force Brigade” against which Reserve Units exercised once every two years. The “Enemy Force Brigade” would, from 1935 on, run some 24 training rotations per year in conjunction with Training Command.

The Finnish Army would go on to make use of the Spanish Civil War to try out in battle all of their doctrine and much of their equipment. This field testing in battle would lead to further rapid changes and perhaps even more rapid development in training, in doctrine and in equipment, while the rotation of some thousands of Finnish volunteers through the battlefields of Spain would give the Finnish Army and Air Force a cadre of Officers and NCO’s with invaluable combat experience. The edge this gave the Finnish Armed Forces in the Winter War was incalculable, but it was certainly effective, as the outcome has shown us.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland