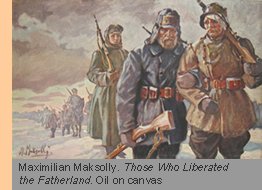

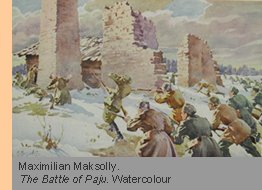

Maximilian Maksolly (actually Feichter, the original spelling of his first name was Maksimilian) was an Estonian painter who is now possibly best remembered for his war art from the time of the Estonian War of Independence. I touch on him in this blog largely because of his series of war paintings of battles involving Pohjan Pohjat, the “Boys from the North”, Finnish volunteers who came to Estonia in late 1918 to aid the Estonians in their war for independence from Russia and the Bolsheviks.

Maximilian Maksolly was born in 1884 in Tallinn, Estonia, the son of a Hungarian father and an Estonian mother. He received a general education in Tallinn, at the St. Peter’s School of Natural Sciences and Arts and then at the Alexander von Stieglitz Art School in St. Petersburg, where he completed his studies in 1909. He worked as an artist in Russia first, and then over 1910-1911 in Germany. He married Klikeria Taigatšovaga in St. Petersburg in 1912, when he was 28 years old. From 1917-1923 he lived in Russia, where he restored murals and painted portraits. In 1923 Maksolly returned to Estonia via Poland where he received payment in 1926 from the Cultural Endowment of Estonia to paint events from the Estonian Liberation War. He was the most prominent painter of these events and between 1924 and 1929 he participated in several exhibitions.

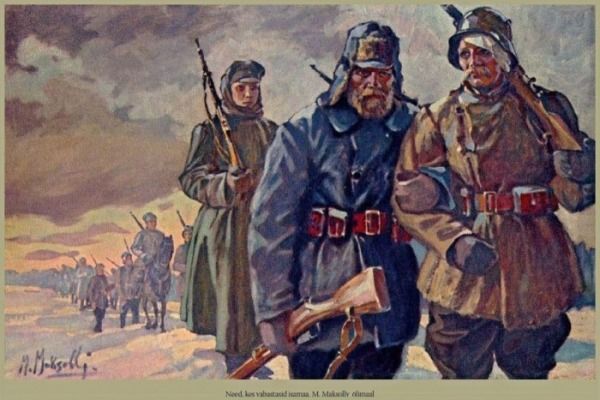

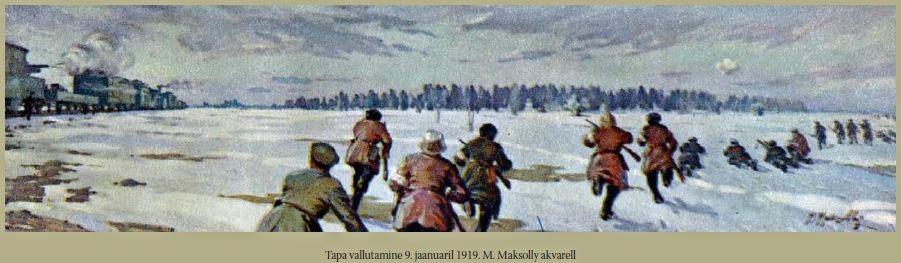

His paintings were placed in military and state institutions, army units, and the War Museum; these paintings were also reproduced as postcards and distributed as images in the press and in books. Maksolly’s best-known paintings are of the “Battle of Paju Manor January 31, 1919” and “Need, kes vabastasid Isamaa” (“Those who freed the fatherland”). Historical painting, especially war painting, is a rare phenomenon in Estonian art; it usually falls outside the general developments in Estonian art and is difficult to treat as an organic part of Estonian art. The first period of Estonian independence came to an abrupt end before the tradition of such thematic painting had time to develop to its fullest, although, during the 1930’s, due to the art politics of the authoritarian state, it had every opportunity to do so. There was also a group of artists who were purposefully engaged in the subject.

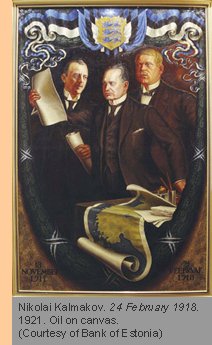

A very small number of these historical paintings that were created in the 1920’s and 1930’s have been preserved. The vast majority of such works perished or were deliberately destroyed during the Soviet occupation. Some works survived the occupation only thanks to the sense of mission of museum staff members, such as Maximilian Maksolly’s “24th of February 1918” (1928), featuring the members of the Committee for National Salvation reading aloud the Manifesto of Independence of the Republic of Estonia in the building of the Credit Bank in Tallinn. The painting was found in the cellar of the Tallinn Town Museum in March 1989, where in 1941 it was stored as part of a collection of “city of Tallinn art pieces.” This ambiguity obviously helped the painting to survive the decades of Soviet occupation – a work wrapped in dark paper and without even a museum inventory number was obviously of no interest. This was more than likely a deliberate attempt to preserve the painting for posterity and for this, we must thank the unnamed and unrecorded member of the museum staff who risked their life to preserve this historic painting.

A very small number of these historical paintings that were created in the 1920’s and 1930’s have been preserved. The vast majority of such works perished or were deliberately destroyed during the Soviet occupation. Some works survived the occupation only thanks to the sense of mission of museum staff members, such as Maximilian Maksolly’s “24th of February 1918” (1928), featuring the members of the Committee for National Salvation reading aloud the Manifesto of Independence of the Republic of Estonia in the building of the Credit Bank in Tallinn. The painting was found in the cellar of the Tallinn Town Museum in March 1989, where in 1941 it was stored as part of a collection of “city of Tallinn art pieces.” This ambiguity obviously helped the painting to survive the decades of Soviet occupation – a work wrapped in dark paper and without even a museum inventory number was obviously of no interest. This was more than likely a deliberate attempt to preserve the painting for posterity and for this, we must thank the unnamed and unrecorded member of the museum staff who risked their life to preserve this historic painting.

The first paintings depicting events from the Estonian War of Independence were created during the War of Independence itself. Several artists, such as Voldemar Kangro-Pool, known for his expressionist and Jugendstil erotic drawings in Indian ink and symbolist wood engravings, expressionist artist Peet Aren, and graphic artist Jüri Riis, worked at the war front. They mostly made sketchy drawings and paintings, which, as a rule, differ from the rest of their work. The first serious thematic compositions were created only at the beginning of the 1920’s. A specific feature of Estonia is that an historical event of national importance – the War of Independence – was first depicted in art media by artists who were not Estonians. The first work on this subject that found wider renown was “24th of February 1918” (1921), painted by Russian Symbolist artist Nikolai Kalmakov, who lived in Estonia in 1920-1922.

The work was exhibited at Kalmakov’s solo exhibition at the Tallinn Provincial Museum in the spring of 1922. The painting features the members of the Committee for National Salvation, Konstantin Konik, Konstantin Päts and Jüri Vilms, and it became the highlight of the exhibition. A heated discussion broke out in the newspapers about the nationality of the artist, as well as about the price the Stock-Exchange Committee had to pay for the painting, since 200,000 marks was, at that time, a rather large sum for one composition of several figures. The painting was most severely criticised by Peet Aren, who during the war had worked at the Museum of the War of Independence established at the Ministry of War, and who had created watercolours and reportage-like drawings on war subjects. Certainly the criticism was partly caused by bitterness over the fact that a Russian artist was able to earn such a large sum of money using a subject from Estonian history. The work itself survived the occupation – it was hidden in the State Archive; now it is on display in the building of the Bank of Estonia.

In the mid-‘1920’s, Maximilian Maksolly, an artist of Hungarian and Estonian lineage who returned to Estonia in 1923, moved powerfully onto the artistic scene. He had traveled in Europe after having graduated from Stieglitz’s school of applied arts, and had lived in Russia since 1917, where he had restored murals and painted portraits. He first found renown as a portrait painter in Estonia; his successful portrait of State Elder Konstantin Päts was followed by a score of orders for portraits of other statesmen. In 1926, the Estonian Army appealed to Estonian artists via the Cultural Endowment, calling for paintings and listing subjects ranging from national mythology and the ancient fight for freedom to the War of Independence.

The aim of the appeal was to get paintings of national content for the army institutions. Although the honoraria were generous, the call did not receive an enthusiastic response. The artists weren’t afraid to establish relations with the authorities. Rather, they were afraid that they could not cope with compositional paintings. Moreover, historical compositions would traditionally have required an academic style, which would have meant regression in the context of the art trends of the 1920’s, which at that time were striving for modernism. Unfortunately, the subject of war did not provoke interest even among expressionist artists, although they could have achieved interesting results. Maksolly, being familiar with academic art, seized the opportunity. However the reception of his works was not favorable; besides criticism on the artistic level, the artist’s possible motives came under attack.

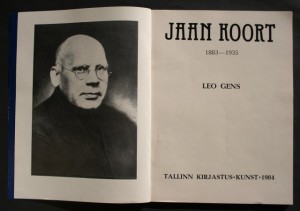

The press initiated a discussion about Maksolly’s nationality, claiming (untruly) that he was a Baltic-German. He was accused of being money-hungry. The exhibition of the members of the Estonian Artists’ Association in 1926, also showing Maksolly’s thematic paintings, provoked devastating criticism from sculptor Jaan Koort. Among other things he called Maksolly an international art adventurist. Other critics spoke in Maksolly’s defence: “We have our history, but what have our artists done about it? … Just as art has to be free and international, artists have to be free of extreme nationalism. Everyone has the freedom to work, and the Ministry of War has enough work to offer all artists who seriously can and want to work, just as Maksolly does.” This comment appeared in the newspaper Kodumaa Hääl in 1926. In spite of criticism, Maksolly’s works became enormously popular among the public, reproductions appeared in all kinds of publications, and a series of postcards were also published. Maksolly’s war paintings have a dynamic structure, are detailed and truthful to the historical events they depict. Much of Maksolly’s work in Estonia was destroyed when the Soviet Union occupied Estonia.

Besides Maksolly, Arnold Vihvelin, who had studied in St.Petersburg, and worked mostly in the academic style, exhibited his works featuring the War of Independence at the same exhibition in 1926. He worked mostly in Rakvere and continued the subject well into the early 1930’s. In 1929, an excursion was organised for the artists to the battlefields of the War of Independence in Latvia with the aim of inspiring them to memorialise the war. Among others, Peet Aren, Roman Nyman, Eduard Ole, and Karl Burman attended the excursion. Maksolly, who had fallen into disgrace in art circles, was not sent an invitation. He left Estonia in the same year. The works completed after the excursion were displayed at an exhibition organised at the Administration of Fine Arts Endowment in Tallinn in 1930; among others, Arnold Vihvelin and A. Kulkov participated in the exhibition. The exhibited paintings did not arouse any public interest.

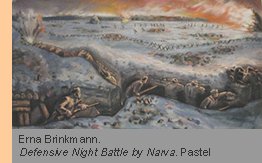

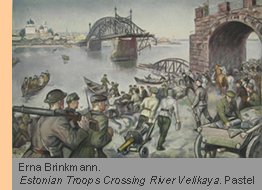

Portrait of Erna Brinkmann, 1936, by Oskar Sädek. Brinkmann was a a German noblewoman who was born in Russia and moved to Estonia in 1914. She left Estonia in 1940 for Germany. But in her heart, Brinkmann continued to live in Estonia, one proof of this is the fact that she left the work she had done in Germany to the Art Museum of Estonia

In 1934, a crisis in domestic policy hit Estonia, and in the resulting coup, the democratic order was replaced by an authoritarian regime, which also affected the artistic world. Professional chambers were established following the example of Italy. In 1934, the Information and Propaganda Department was created by the government but still, mass production of propagandist art, which was so typical of the time, did not emerge in Estonia. War paintings had only a secondary role in the work of the majority of artists who created them; quite often it was a case of a single painting, standing far outside the rest of the artist’s work, being perhaps only an experiment. Very few artists continued working on the subject of the war. Art critics rarely paid attention to war paintings; most probably there was no reason to talk about them. War paintings were a marginal area in Estonian art, but there was still a widespread social subscription for them, as we can see from the appeals, competitions and orders. It is true that in the 1930’s the number of war paintings continued to grow, although slowly. This was caused by the art politics of the authoritarian state, allowing larger grants and honoraria for ideologically suitable artworks.

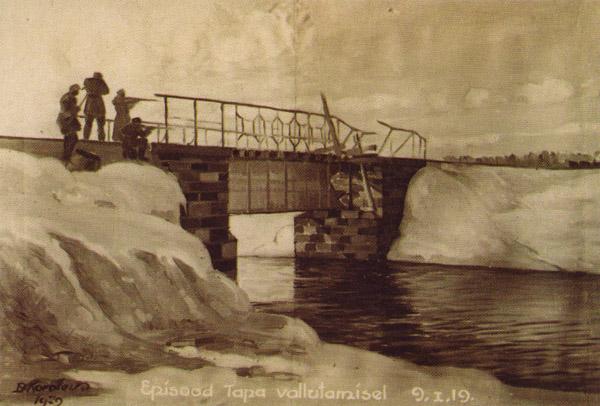

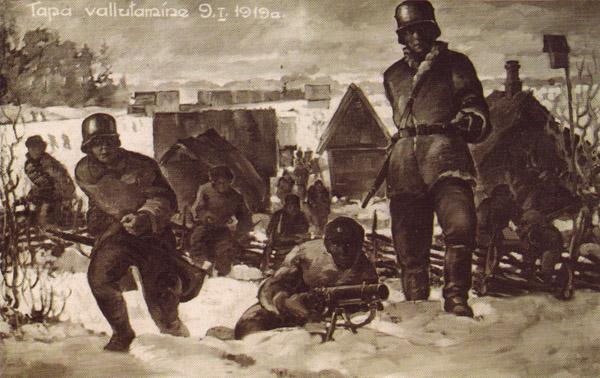

In 1934, the Museum of the War of Independence and the Union of Applied Artists announced a competition of war paintings with the aim of getting postcard designs on the subject. Twenty artists participated in the competition; the first award was given to B. Korolev, the second to A. Kulkov. 6 The works, which have not been preserved, were displayed at the Museum of the War of Independence from 4 to 12 March 1934. In the spring of 1935, the Administration of Fine Arts Endowment together with the Committee of the History of the War of Independence again organised a competition of war paintings, aiming at receiving illustrations for the two-volume publication The Estonian War of Independence. The illustrations of the publication were selected from the works submitted to the competition, and other works specially commissioned from certain artists were used as well 7. “The general impression is that it is a difficult subject well above the reach of the majority of competitors. Maybe even above the reach of the jury… This difficult task is made even more difficult and complex by the requirement of depicting not just any war, but our own war, our war of independence, our fight with the oppressive powers. In short, to depict the heroic era of the Estonian nation, the rise of its heroism and its development – in single episodes”, wrote one of the leading art critics at the time, Hanno Kompus.

In 1934, the Museum of the War of Independence and the Union of Applied Artists announced a competition of war paintings with the aim of getting postcard designs on the subject. Twenty artists participated in the competition; the first award was given to B. Korolev, the second to A. Kulkov. 6 The works, which have not been preserved, were displayed at the Museum of the War of Independence from 4 to 12 March 1934. In the spring of 1935, the Administration of Fine Arts Endowment together with the Committee of the History of the War of Independence again organised a competition of war paintings, aiming at receiving illustrations for the two-volume publication The Estonian War of Independence. The illustrations of the publication were selected from the works submitted to the competition, and other works specially commissioned from certain artists were used as well 7. “The general impression is that it is a difficult subject well above the reach of the majority of competitors. Maybe even above the reach of the jury… This difficult task is made even more difficult and complex by the requirement of depicting not just any war, but our own war, our war of independence, our fight with the oppressive powers. In short, to depict the heroic era of the Estonian nation, the rise of its heroism and its development – in single episodes”, wrote one of the leading art critics at the time, Hanno Kompus.

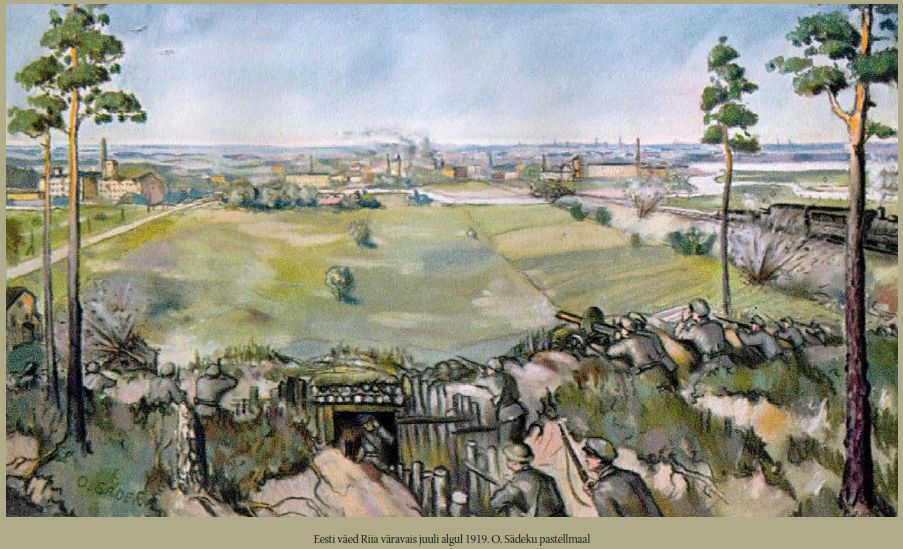

Awards were given to Nikolai Kull, a painter of town- and seascapes, to portrait painter Erna Brinkmann and to Oskar Sädek, among others. The latter two submitted war paintings to the Estonian Academic Association of Professional Artists exhibition in 1937 as well. All these artists had, for longer or shorter periods, been the students of Ants Laikmaa’s studio school; Brinkmann and Sädek belonged to a special circle of friends meeting at the studio. At the 19th exhibition held by the Art Society Pallas, besides his customary landscapes, Juhan Pütsep displayed the historical composition “Jüri Vilms On His Way To Finland”, featuring an Estonian politician of tragic fate, who had been executed in Finland in 1918 under circumstances which have remained unclear even up to the present.

Awards were given to Nikolai Kull, a painter of town- and seascapes, to portrait painter Erna Brinkmann and to Oskar Sädek, among others. The latter two submitted war paintings to the Estonian Academic Association of Professional Artists exhibition in 1937 as well. All these artists had, for longer or shorter periods, been the students of Ants Laikmaa’s studio school; Brinkmann and Sädek belonged to a special circle of friends meeting at the studio. At the 19th exhibition held by the Art Society Pallas, besides his customary landscapes, Juhan Pütsep displayed the historical composition “Jüri Vilms On His Way To Finland”, featuring an Estonian politician of tragic fate, who had been executed in Finland in 1918 under circumstances which have remained unclear even up to the present.

Nowadays, the cultural and historical value of the few historical war paintings that survived the Soviet occupation is more important than their artistic value. The young Estonian state needed myths and symbols that could unite its people and boost patriotism. In acting as the disseminator of these myths and fixing them in people’s minds, art gave a face to history.

Returning now to Maksolly, he left Estonia in 1929 for Prague, where he worked as an artist in many parts of the country. He later moved to the United States and after the Second World War, left the USA in 1948 to live in Brazil. Maximilian Maksolly died on 9 September 1968 in Rio de Janeiro and is buried in the there in the cemetery of São João Batista.

Sünnipäevaõnnitlused Eesti riigile!

Sources:

Representation of the Estonian War of Independence in Paintings of the 1920s and 1930s by Kristina Valdru

Wikipedia – Maksimilian Maksolly (in Estonian)

The Art of Maximilian Maksolly

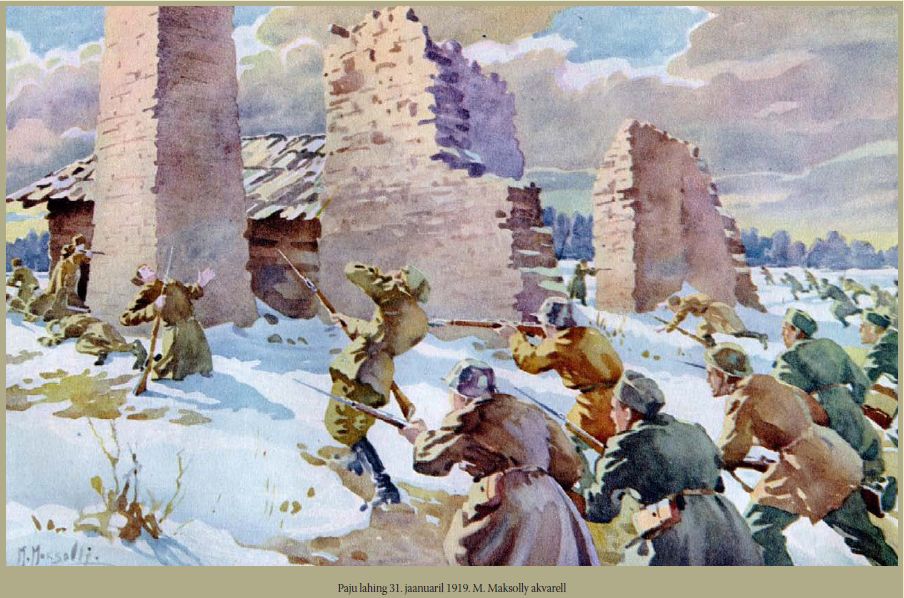

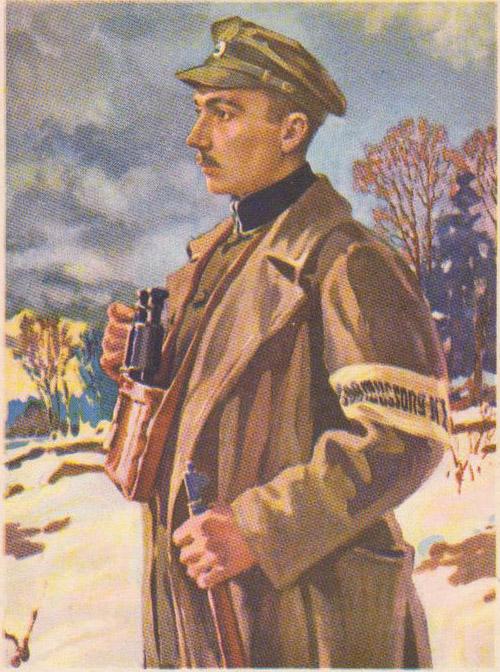

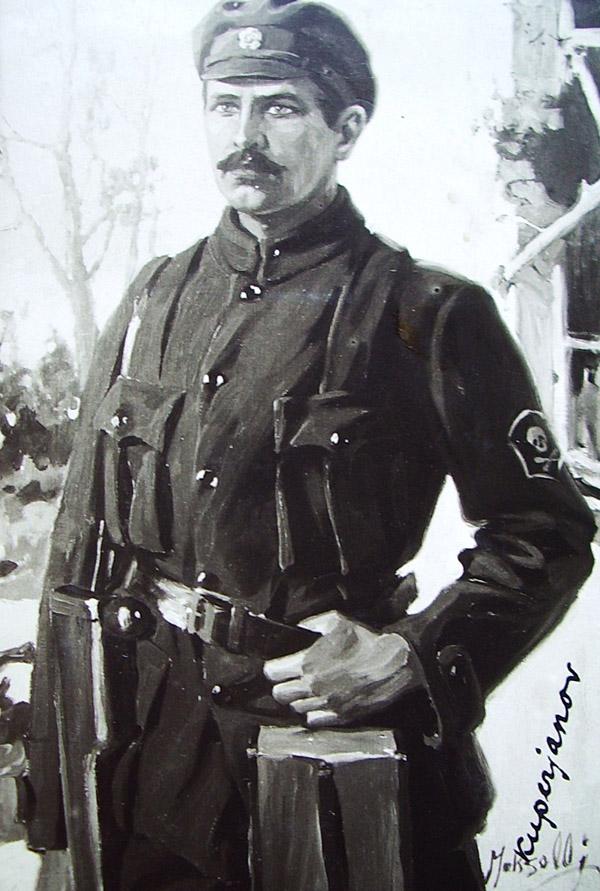

The Battle of Paju (Paju lahing) was fought in Paju, near Valga, Estonia, on 31 January 1919 during the Estonian War of Independence. After heavy fighting, the Tartu–Valga group of the Estonian Army pushed the Red Latvian Riflemen out of the Paju Manor. It was the fiercest battle fought in the early period of war. The Estonian commander Julius Kuperjanov fell in the fighting. In early January 1919, Estonian forces had started a full scale counterattack against invading Soviets. Their main objective was liberating north Estonia including Narva, which was achieved by 17 January. They then started to advance into south Estonia. On 14 January, the Tartumaa Partisan Battalion, organised and led by Lieutenant Julius Kuperjanov, and using armoured trains, liberated Tartu.

At that time the only working railway connection to Riga, which the Red Army had captured on 3 January, passed through Valga, so defending it had strategic importance for Soviet Russia. Among other units, a large part of the elite Latvian Riflemen were sent to stop the Estonians. Commander-in-chief, Johan Laidoner reinforced the Estonian advance in the south, including Finnish volunteers, Pohjan Pohjat (The Sons of the North), led by Finnish Colonel Hans Kalm. Finnish general Paul Martin Wetzer became the commander of the southern front. To liberate Valga it was necessary to capture Paju Manor. On 30 January Estonian partisans had captured it, but were soon pushed out. With his 300 men, 2 guns and 13 machineguns, Kuperjanov decided to recapture Paju on 31 January. Armoured trains were unable to provide support, due to the destruction of the Sangaste railway bridge. The Latvian Riflemen had about 1,200 men with 4 guns and 32 machineguns. They were supported by an armoured train and armoured cars.

Tartumaa Partisan Battalion attacked the manor directly over open fields. At 400 metres Bolshevik troops opened fire inflicting heavy casualties. Kuperjanov led the attack personally, as usual, and was fatally wounded, dying two days later. When he was hit, Lt Johannes Soodla took command of the battalion. Later Finnish Pohjan Pohjat units with about 380 men arrived, bringing with them 4 guns and 9 machineguns. They also assaulted the manor in a frontal attack which caused heavy losses. In the evening the Estonians and Finns finally pushed into the park of the estate where heavy hand-to-hand combat started, which resulted in capturing the manor. Retreating Latvian Riflemen were taken under heavy fire. Next day the Estonians marched into Valga without resistance. The victory cut off the Soviets’ railway supply line and denied them the use of armoured trains. Soon almost all southern Estonia was liberated and Estonian troops advanced into northern Latvia.

To honour Julius Kuperjanov who died of wounds on 2 February, Tartumaa Partisan Battalion was renamed Kuperjanov’s Partisan Battalion. The current Estonian Defence Force has resumed this tradition following the collapse of the Soviet Occupation and once more includes the Kuperjanov Battalion. The battle is commemorated by a granite monument on a three–step pyramid of earth, which was reopened by the Estonian President Lennart Meri in 1994 on the 75th anniversary of the battle.

The Estonian Declaration of Independence, also known as the Manifesto to the Peoples of Estonia, is the founding act of the Republic of Estonia from 1918. It is celebrated on 24 February, the National Day or Estonian Independence Day. The declaration was drafted by the Salvation Committee elected by the elders of the Estonian Provincial Assembly. Originally intended to be proclaimed on 21 February 1918, the proclamation was delayed until the evening of 23 February, when the manifesto was printed and read out aloud publicly in Pärnu. On the next day, 24 February, the manifesto was printed and distributed in the capital, Tallinn. Malsolly’s famous painting shows Jüri Vilms, Konstantin Päts and Konstantin Konik reading the Manifesto.

Maksimilian Maksolly, Russians and Estonians at Treaty of Tartu: Centre – Jaan Poska (left) and Julius Seljanaa (right), General Jan Soots, Kolonel Viktor Mutt, Ants Piip, Rudolf Paabo

The Art of Other Estonian War Artists

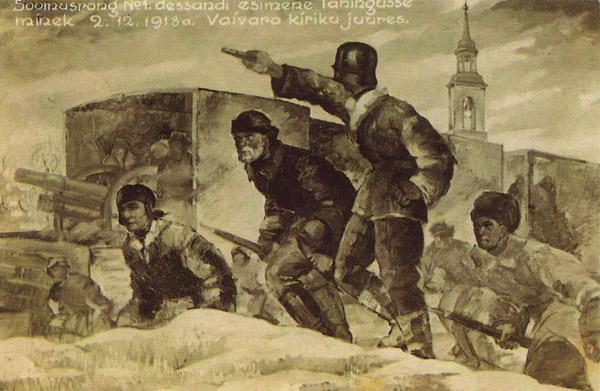

B. Korolev “Soomusrong nr. 1. dessandi esimene lahingusse minek 2.Dec.1918 Vaivara kiriku juures” – Going into action at Vaivara Church

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland