Later in this thread, we looked at the origins of the Suojeluskunta in the Finnish Civil War and the preceding unrest. In this post, we will largely look at the Finnish Red`s who fled to the Soviet Union in the aftermath of the Finnish Civil War and at their counterparts on the Finnish Right.

As the turmoil of the Great War and the Revolution in Russia finally calmed down along the Finnish borders in the early 1920s, many Conservatives had already begun to feel that the “War of Liberation” had ended too soon and in an inconclusive fashion. New critics joined in the public discussion by openly accusing the political leadership of wasting what some now saw as a unique opportunity for territorial expansion into the historic Finnish lands of Eastern Karelia by signing the Treaty of Tartu – some went even further, cursing the moderate politicians for their decision to stay out of the Russian Civil War, thus allowing the Bolsheviks to retain their hold on Petrograd and indirectly helping them to win. Back at home many felt there were still accounts to be settled with the radical left. The survival of the SDP as the strongest political force in the country was especially galling for many White veterans of the Civil War.

AKS Poster

In the 1920s, the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura (the Academic Karelia Society or AKS) soon became the dominant group among Finnish university students after three volunteer veterans of the Heimosodat (Kinship Wars) had created the organisation in March 1922 (and in fact the AKS controlled the student union of the University of Helsinki from the mid-1920s right up to 1944, when, OTL, it was disbanded). Its members often retained their membership after their student days ended and the AKS therefore quickly expanded its influence among young civil servants, teachers, lawyers, physicians and clergymen as well as in the officer-class of the Army throughout the country during the 1920s. Most Lutheran clergymen had been strongly pro-White during the Civil War and the influence of the AKS further increased the nationalistic character of the Finnish Lutheran Church – and the Lutheran Church was one of the most influential organizations for the changing of public opinion in the country. The AKS and its propaganda focused on “uniting the oppressed tribe of Karelians with rest of Finland” strongly affecting the worldview of the entire first generation of educated Finns living in independent Finland, resulting in a common mood that was relentlessly anti-Soviet and expansionistic.

The AKS’ 20 year anniversary book (1942): “Me Uskomme / We Believe”.

The AKS’ 20 year anniversary book (1942): “Me Uskomme / We Believe”. OTL, the organization was banned in 1944 – after the Finnish government broke its alliance with Germany — as a “fascist” organization. One of the important goals of the AKS was to unite the Finno-Ugrian-speaking areas of Soviet Karelia which were traditionally Finnish into Greater Finland. Stalin sent many thousands of Karelian and Ingrian Finns to their deaths in Siberia and Central Asia both before and after the war, and brought in Russians to replace them. Today, in most of Soviet Karelia and Ingria only Russian is spoken – after 2.000 years of being the Finnish heartland, almost no Finnish peoples remain.

The political and philosophical ideology of the AKS had its main roots in the philosophy of the 19th century Finnish statesman Johan Vilhelm Snellman, who emphasized a strong national state and the need to bring the Finnish language into the forefront of Finnish cultural life, which was at that time dominated almost exclusively by the Swedish language. The nationalistic ideology of the AKS also stemmed from the common European discussion of national rights based on the 14 points of President Wilson. The experience of the Finnish Civil War bolstered a deep anti-socialist sentiment in Finnish nationalist circles of that time. One of the slogans the AKS used was “Pirua ja Ryssää Vastaan!” (“Against the Devil and the Ruskies!”) where the devil is a reference to the Society’s main domestic enemies, the socialists and the communists. Despite holding views that might be seen as similar to those of the Fascist movement of Italy, there were no influences from abroad – the AKS was founded before the Fascist march on Rome and its origins were purely domestic. The group was founded by Elias Simojoki, Erkki Räikkönen and Reino Vähäkallio. The initiation ceremony involved among other things kissing the flag of the AKS, within which was sown the bullet that Bobi Siven had shot himself with (Sivén, a Finnish nationalist, had shot himself in protest when Finland relinquished control of the Repola and Porajärvi Parishes to the Soviet Union in accordance with the Treaty of Dorpat). All members taking the oath for the order kissed the flag and the bullet in the initiation ceremony.

Akateeminen Karjala-Seura. Sällskapet odlade flitigt olika ritualer. I fanan som användes i sådana sammanhang hade man sytt in den kula som ändade martyren Bobi Sivéns liv. Här ett fackeltåg vid dennes grav på tioårsdagen av organisationens grundande 22/ 2 1932.

Many of the founders of the AKS were veterans of the Karelian wars and thus had first-hand knowledge of the plight of the Karelian-speaking population in Soviet Karelia. The Karelians were considered to be a part of the Finnish heimo (folk) and their fate was of the utmost importance for the AKS. The Academic Karelia Society’s program was centered on their main demand: the liberation of Eastern Karelia from Soviet Russia and the freeing of the Karelian kinfolk. Working towards this goal was mainly done by propagandist efforts to keep the matter in the public eye. The AKS also organized aid to Finnic minorities in Soviet Russia and refugees from there and promoted cultural efforts to help the Finnish-speaking minorities of northern Sweden and Norway. They also tried to cultivate a closer friendship between the newly independent states of Finland and the Finno-Ugric states of Estonia (and to lesser degree Hungary).

Many of the founders of the AKS were veterans of the Karelian wars and thus had first-hand knowledge of the plight of the Karelian-speaking population in Soviet Karelia. The Karelians were considered to be a part of the Finnish heimo (folk) and their fate was of the utmost importance for the AKS. The Academic Karelia Society’s program was centered on their main demand: the liberation of Eastern Karelia from Soviet Russia and the freeing of the Karelian kinfolk. Working towards this goal was mainly done by propagandist efforts to keep the matter in the public eye. The AKS also organized aid to Finnic minorities in Soviet Russia and refugees from there and promoted cultural efforts to help the Finnish-speaking minorities of northern Sweden and Norway. They also tried to cultivate a closer friendship between the newly independent states of Finland and the Finno-Ugric states of Estonia (and to lesser degree Hungary).

Domestically the AKS was an emphatic proponent of a strengthened army and for strict restrictions against Socialists and Communists, although at the same time the AKS stressed the need for improving the lot of the working classes in the interests of the national community. It also promoted the Finnish language becoming the first language in the country, especially in the Universities and in the state bureaucracy. Initially the group was ambivalent towards democracy but under the chairmanship of Vilho Helanen it came to oppose the concept. As a result, in the 1930s, the AKS was an ally of the ultra-right Patriotic People’s Movement party (IKL). The AKS also maintained close ties with a militant secret society called Vihan Veljet (literal translation from Finnish: “Brothers of Hate” – this was a militant clandestine group within the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura (AKS). Members swore a blood oath to foster and uphold hatred toward the Russian people. Some authors claim that Vihan Veljet was actually a group inside the AKS, not a separate organization, but there is not much evidence either way).

OTL, after the end of World War II, the organization was labeled “fascistic” and officially disbanded on the order of the Allied Control Commission, and the archives of AKS were hidden or destroyed. Prominent former members include many academics, bishops, business leaders, generals and politicians (e.g. president Urho Kekkonen). Many officers of the Finnish army during the wars of 1939–1940 and 1941–1944 were members of the Society.

Note: By way of further background, a subsequent post will give a brief overview of the historically Finnish lands within the Soviet Union, their history and their subsequent fate at the hands of the Russians both before and after WW2.

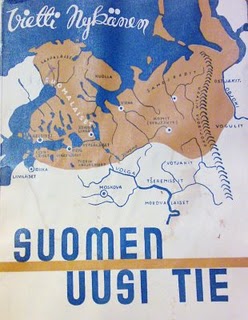

This gives some idea of the areas that the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura rightly considered to be part of “Greater Finland” by virtue of being traditionally inhabited by Finno-Ugric speakers.

This gives some idea of the areas that the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura rightly considered to be part of “Greater Finland” by virtue of being traditionally inhabited by Finno-Ugric speakers. In particular, the territories along the eastern border of Finland to the White Sea, which had for as long as history has been recorded been populated by Finnish Karelians were called Eastern Karelia in Finland. Most of the poems in the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, were collected from this area and as the ideas of Finnish nationalism gained ground at the end of the 19th century, supporters of a Great Finland hoped that the territory would be incorporated to Finland. The Finnish populations of theses territories were not at the time inspired by the same idea, most of them were members of the Russian Orthodox Church rather than Lutherans and preferred the traditional Russian administration, referring to the Finns from Finland as “Swedes”.

At the beginning of 1918, the supporters of “greater Finland” began to organize expeditions in order to persuade the Eastern Karelians to join Finland. The Senate and the Commander-in-Chief (Mannerheim) supported the projects. Mannerheim even went a step further and promised not to put his sword into the scabbard (the Order of the Day of the Sword Scabbard), until White Karelia and Aunus were liberated from Lenin’s “hooligans”. This led to fighting between the Allies and Allied-supported forces and the Finnish expeditionary forces in the region as the Allies sought to keep the Murmansk Railway in Russian hands so as to enable military supplies to continue to be transported to the Russian military as the Allies endeavoured to keep the Russians in the War against Germany. Perhaps unfortunately for the dreams of the Finnish nationalists, the Finnish alliance with Germany at the time firmly placed Finland in the enemy camp and meant that the Allies actively fought against them in 1918.

After Germany and Russia signed the Brest Peace Treaty on 3 March, 1918, the policy of the Finnish government became more cautious. In April and May 1918, preparations were made in Mannerheim’s headquarters for an operation in Aunus, in order to encourage “Finnish” thinking and to assist the Russian White forces in the liberation of St Petersburg from the Bolsheviks. The Senate, however, prevented this project from being carried out. Mannerheim believed that the White Russians would show their gratitude by ceding Eastern Karelia to Finland. The idea of incorporating Eastern Karelia into Finland became more intense during the Heimosodat (Kinship War) expeditions of 1918-1922, and afterwards when the members of the Akateeminen Karjala Seura (Academic Karelia Association), became rather more powerful and influential. After 1922 Mannerheim did not publicly give his support to these projects and in the 1930s they were overshadowed by other issues, but as we will see, the issue again came to the fore after the Winter War broke out.

A Note on leading members of the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura

Erkki Räikkönen

Erkki Aleksanteri Räikkönen: (August 13, 1900, St Petersburg – March 30, 1961) was a Finnish nationalist leader. He attended the University of Helsinki before taking part as a Volunteer in the ill-fated mission to secure independence for Karelia in 1921. Like most of those who took part in this action he joined the Academic Karelia Society (AKS), in his case helping to found the movement along with Elias Simojoki and Reino Vähäkallio. He quit the AKS in 1928 to join the Itsenäisyyden Liitto (Independence League), a group that had been formed by Pehr Evind Svinhufvud, Räikkönen’s most admired political figure. Räikkönen took this decision in response to the banning of the Lapua Movement, a move that had left the far right in Finland without a wide organisational basis (groups like the AKS only having a small, elite membership).

Along with Herman Gummerus and Vilho Annala, Räikkönen was the founder of the Patriotic People’s Movement (IKL) in 1932. He would not stay a member long however as the group soon became purely Finnish (isolating the Swedish-speaking Räikkönen) and moved closer to Fascism, which he opposed. After leaving the movement he contented himself with editing the journal Suomen Vapaussota, whilst also becoming involved in the Gustav Vasa movement, a right wing organization for Finland’s Swedish-speaking population. He ultimately emigrated to Sweden in 1945 and lived out his life there in retirement.

Vilho Veikko Päiviö Helanen: (24 November 1899, Oulu – 8 June 1952, Frankfurt, West Germany). Vilho Helanen was a Finnish civil servant and politician. A student as the University of Helsinki he gained an MA in 1923 and completed his doctorate in 1940. From 1924 to 1926 he edited the student paper Ylioppilaslehti and around this time also joined the Academic Karelia Society. He served as chairman of the group from 1927-8, from 1934-5 and again from 1935-44, helping to turn the Society against democracy. Helanen visited Estonia in 1933 and was amazed at the high levels of popular support for the far right that he witnessed there, in contrast to Finland where it was a more marginal force.

As a result he was involved in the coup attempt of the Vaps Movement in Estonia in 1935. Helanen was a major inspiration for the Patriotic People’s Movement and a close friend of Elias Simojoki, although he did not join the group. He formed his own group, Nouseva Suomi, in 1940 which, despite his earlier radicalism, became associated with the mainstream National Progressive Party. Rising to be head of the civil service during the Second World War he was imprisoned after the war for treasonable offences. Following his release he worked for Suomi-Filmi and also wrote a series of detective novels.

Lauri Elias Simojoki (28 January 189, Rautio – 25 January 1940)

Lauri Elias Simojoki: (28 January 189, Rautio – 25 January 1940) was a Finnish clergyman who became a leading figure in the country’s far right movement. Himself the son of a clergyman, as a youth he saw service in the struggle for Finnish independence and then with the Forest Guerrillas in East Karelia. A student in theology at the University of Helsinki, he became involved in the formation of Academic Karelia Society, serving as chairman from 1922-3 and secretary from 1923-4. He advocated the union of all Finnish people into a Greater Finland whilst in this post. Strongly influenced by Russophobia, the student Simojoki addressed a rally on ‘Kalevala Day’ in 1923 with the slogan “death to the Ruskis”, after accusing Russia of dividing “the Kalevala race”.

Simojoki was ordained as a minister in 1925 and he held the chaplaincy at Kiuruvesi from 1929 until his death. He became involved with the Patriotic People’s Movement and, in 1933, set up their youth movement, Sinimustat (The Blue-and-Blacks), which looked for inspiration to similar movements amongst fascist parties in Germany and Italy. The movement was banned in 1936 due to its involvement in revolutionary activity in Estonia, although Simojoki continued to serve as a leading member of the Patriotic People’s Movement. He was a Member of Parliament from 1933-1939 and founded a second youth group, Mustapaidat (the Black Shirts), in 1937, although this proved less successful. When the Winter War broke out in 1939 Simojoki enlisted as a chaplain in the Finnish Army. He was shot on active duty, while putting down a wounded horse in no man’s land, and died of his wounds on 25 January 1940.

And on the other side of the political spectrum….

1928. The Karelian Jäger Battalion on parade in Petrozavodsk

On the other side of the political spectrum, the Finnish Communists equally felt that the Civil War had been only the beginning of their struggle against their counter-revolutionary opponents. Openly backed by a steadily strengthening Soviet Union, the Communist Party of Finland, the SKP, trained new “Red” military forces in Soviet Karelia where radicalized former Social Democratic leaders and over 5000 refugees from the Red side of the Civil War were actually promoting virtually similar goals to their Conservative opponents – the unification of Eastern Karelia and Finland, except in their case, under the Communists. As a result of their work Finnish was the second official language in the new Karelian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, and propaganda broadcasts from the Petroskoi (Петрозаво́дск) Radio openly threatened listeners in Finland that the day of reckoning would soon come.

New cadres of Red Finnish officer cadets were trained annually in Leningrad, and after the failed uprisings of the 1920s the Red Army even organized a Karelian unit of their own in the form of the Karelian Jaeger Brigade (Каре́льская е́герская брига́да). Because of the fresh memories of the Heimosodat (Kinship Wars) and the postwar status of Eastern Karelia as a “Red Piedmonte” where Finnish revolutionaries were clearly preparing for revanche, the official relations between Helsinki and Moscow were thus understandably icy.

March 12, 1930. The first company of the Karelian Jäger Battalion

After the suppression of the Karelian uprising of 1921-1922 the Central Committee of C.P.S.U.(B.) on March 5th 1922 decided to start Finnicising the Karelian Labour Commune. The leadership of the Karelian Labour Commune went to the so-called “Red Finns”. The Finnish language became the official language in the Commune and was used as the main language in Karelian schools and as the language used for cultural and political work among Karelians. On July 25th 1925 the Karelian Labour Commune was transformed into the Autonomous Karelian Soviet Socialist Republic (AKSSR). From a political perspective the “Red Finns” saw the AKSSR as the outpost of the “world revolution” in the North of Europe. There objective was to expand the AKSSR into “The great Red Finland” and even “Red Scandinavia”.

This policy also included the creating of a special national military unit within the AKSSR. On October 15th 1925 in Petrozavodsk the Karelian Jäger Battalion was established personally by the Chairman of the AKSSR Soviet People’s Commissar Edvard Gylling. The battalion consisted of four companies, with the battalion quarters in Petrozavodsk, in the buildings of the former Orthodox theological seminary on Gogol Street. The first battalion commander was Eyolf Igneus-Mattson, holding the position till 1928. The first commissar was A.Mantere. In 1927 he was replaced by Urho Antikainen. In October 1931 “due to the aggressive external policy of Finland towards the USSR” and because of the high number of convicts in the territory of the AKSSR, the battalion was transformed into the Karelian Jäger Brigade. The Brigade formation was completed by December 25th 1931. The brigade commander, by recommendation of Edvard Gylling, was Eyolf Igneus-Mattson.

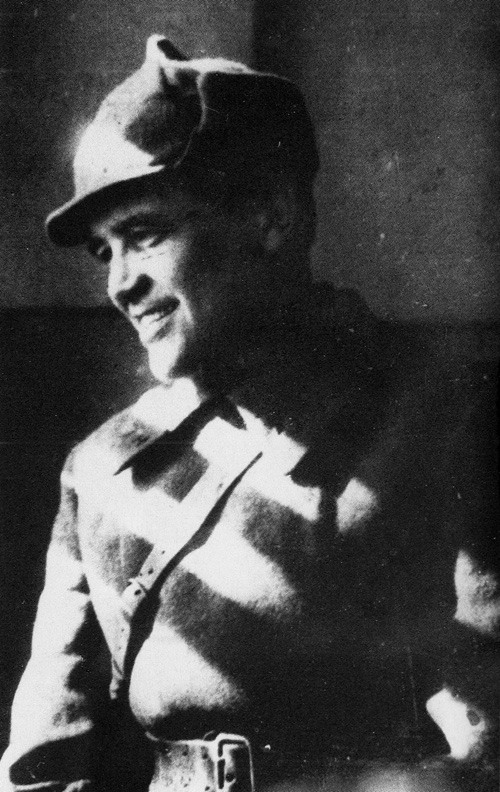

Eyolf Igneus-Mattson

Eyolf Igneus-Mattson was born to a well-to-do Swedish family on the Åland Islands (Finland) in 1897. He graduated from the Higher Technical School in Helsinki and participated in the Red revolt, after the defeat of which he escaped to Soviet Russia, where he finished military training at the Petrograd International Military School. From the summer 1919 he was the commander of the 2nd Battalion of the 164th Infantry Regiment (in August 1919 renamed the 2nd Finnish Regiment), he took part in the battle at Sulazhgora Heights and was decorated with the Order of the Red Banner. He graduated from the Military Academy of the Red Army. From 1925-1928 he was the commander of the detached Karelian Jäger Battalion, from 1931-1934 commander of the detached Karelian Jäger Brigade. In November 26th 1935 he was promoted to the rank of Kombrig (Brigade General). In 1936 became the head of the sub-faculty of general tactics in the M.Frunze Military Academy of the Red Army. In May 28th 1936 he was arrested. He was released in 1946, rehabilitated in 1957 and died on May 25th 1965.

The Karelian Jäger Brigade consisted of two Jäger Battalions (the Petrozavodsk and the Olonets), one artillery battalion, one field company and one communications company. The Brigade was a territorial military unit – the soldiers served their five-year terms near their homes by way of serving several 8 to 12 months musters. In the case of mobilization two more battalions would be formed (the Zaonezhsky and the Vepsky). In June 1932, when the Karelian registration and enlistment office was liquidated, the Brigade Headquarters was supplemented with enlistment and quartermaster departments. The territorial formation of military units was usual for the Red Army at the time, but the name “Jäger” was unique within the Red Army. It was proposed by the leadership of the AKSSR as an analog of the Finnish jäger units. Another big difference was that all commanding posts it the Brigade were held by Finns and Karelians.

The Karelian Jäger Brigade was the only military unit on the territory of the AKSSR. In the case of war with Finland the Brigade operational plans were to cover Petrozavodsk from a Finnish invasion. The last stand, as in 1919, was planned to be the Sulashgora Heights. As an alternative there were plans to move the Brigade to the Kola Peninsula to repel any British landing forces. The activities of the “Red Finns” were carried on to a background of increasing political repression. In the spring of 1930 the OGPU arrested a group of “Red Finns” holding commanding positions in the detached Karelian Jäger Battalion. A second wave of arrests began in 1932 and involved mainly the officers of the 2nd (Olonets) Battalion of the detached Karelian Jäger Brigade. 20 men were shot as a result of the investigation for “counterrevolusionary rebel organisation”.

In 1933 the OGPU “disclosed” the so called “plot of the Finnish General Headqurters”. Some of the commanding officers of the detached Karelian Jäger Brigade were subjected to arrest and removed from their positons. From January 1934 a Josef Kalvan was appointed as brigade commander (known as “The Latvian”, Kalvan was born in January 25th, 1896 to a peasant family. He was decorated with the three Orders of the Red Banner. In November 26th 1935 he was conferred the rank of Kombrig (Brigade General). He was arrested on December 2nd 1937 and executed on September 12nd, 1938) and in 1935 the “Red Finns” were removed from the all leadership positions in Karelia and the detached Karelian Jäger Brigade was disbanded. At the end of 1935 the 18th Yaroslavl Infantry Division was stationed on the territory of AKSSR, with some units of the Karelian brigade now incuded within this Division. The majority of the Officers, NCO’s and Soldiers of the Karelian Jäger Brigade were killed during the mass political repressions of the later 1930’s.

Karelian jäger battalion on the march, early 1930`s

The Karelian ASSR NKVD “… found and destroyed a counterrevolutionary rebel organisation. This organisation emerged in 1920 with the coming to Karelia of the group of bourgeois nationalists: Gylling, Mäki and Forsten, that held leadership positions on the Karelian Revolutionary Committee. By spreading their counterrevolutionary activity and including into it Finnish and Swedish political emigrants, former members of Finnish Social-Democratic Party Rovio, Matson⁸, Vilmi, Usenius, Saksman, Jarvimäki and others this counter-revolutionary group seized the main Party and Soviets posts in Karelia. The activities of this counterrevolutionary organisation were directed towards the intervention and capture of Soviet Karelia by Finland…Holding the main commanding posts in Karelia this nationalist organisation organised … preparation of armed uprising by the means of … creating of the infantry jäger brigade, staffed by national commanding and political officers. In this brigade they spread their counterrevolutionary propaganda and used it as a base for creating rebel organisations on the all territories of the Republic, this activity was performed in close junction with the “rights”, working in Karelia…”

The draft of the “unreliable” Finns and Karelians into Red Army was stopped by 1938. By the end of summer 1939 the few remaining Finnish officers were called from the reserve and in the middle of November there was a mass draft of Finns and Karelians. At the time in Petrosavodsk was formed the 1st Infantry Corps of the so called “Finnish People’s Army”… “(The Corps commander and Minister of Defence in the government of the puppet Finnish Democratic Republic was Komdiv (Division General) Aksel Anttila – former Karelian Jäger Brigade Headquarters Deputy Chief).

An interesting Case Study: Edvard Gylling, Chairman of the AKSSR Soviet People’s Commissar and “Karelian Fever”

April 1, 1932. Edvard Gylling and Eyolf Igneus-Mattson

Edvard Otto Vilhelm Gylling (30 November 1881, Kuopio – 14 June 1938) was a prominent Social Democratic politician in Finland and later the leader of Soviet Karelia. He was a member of the Finnish Parliament for the Social Democratic Party of Finland from 1908–1917 and was active during the Finnish Civil War as the Commissar of Finance for the revolutionary “red” Finnish government. On 1 March 1918, when a Treaty between the socialist governments of Russia and Finland was signed in St Petersburg, the Treaty was signed by Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin from the Russian side and by Council of the Peoples Representatives of Finland Edvard Gylling and Oskari Tokoi. After the Reds lost the war, Gylling fled to Sweden but later moved to the Soviet Union. He became one of the main leaders of the Karelo-Finnish ASSR as Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Karelo-Finnish SSR from 1920–1935. He was accused of nationalism, removed in 1935 and arrested in 1937. There are some contradictions concerning Gyllings death. According to earlier Soviet sources, Gylling died in August 1944, but according to other sources he was actually executed earlier, 1940 or 1938. According to the most recent information, the most likely date of his execution was 14 June 1938.

Edvard Gylling

Gylling more than anyone else was responsible for what has become known as Karelian Fever. Karelian Fever struck in the United States and Canada in the early 1930s, affecting mainly, but not exclusively, first generation Finnish-Americans. Finnish immigrants to North America were divided roughly into two categories: the Church Finns and the Hall Finns; the latter tended to lean to the left politically and some were active Communists. When recruiters went to the Halls to extol the virtues of the Russian Soviet way of life, many were tempted to leave America. The Depression was making life very difficult for farmers, miners, woods workers and small business owners; they were “experiencing the ruthless exploitation of capitalism.” At the time, an interesting situation prevailed in Karelia, the Russian province located near the southwestern border of Finland. Dr. Edvard Gylling, a brilliant Finnish Communist, had become the prime minister of the province and hoped to make it a mainly Finnish-speaking area. In the first Russian Five-Year-Plan strategists assigned production quotas for Karelia which Gylling knew could not be met without financial help and skilled workers from other countries, specifically the United States and Canada. So the call went out for Finnish-speaking construction workers, loggers and fishermen to come to the “workers’ paradise” and bring money and equipment with them.

Inasmuch as the first generation of American Finns could read English only with difficulty, they got a very slanted picture of conditions in Russia from the Finnish Communist papers, the Tymies and Eteenpain. According to Mayme Sevander who has done serious research on the topic, as of 1996 she had identified 5,596 people who responded to the call, selling their belongings in North America and taking the money to Karelia. Boatloads of several hundred sailed together to the strains of the Internationale and the waving of red flags. They were an idealistic people, willing to work hard to establish a new society. The largest groups left in 1930-31, but by 1934 the size of the groups had diminished to as low as eight or ten. Of the almost 6,000 who emigrated, only 1,346 returned. Seven-hundred-ninety men and sixty-three women are known to have been executed during Stalins purges; many others died in labor camps of starvation during the Finnish-Russian War and during World War II. Some still live in Karelia. (See “From Soviet Bondage” by Sevander, 1996).

If you’d like to read more on this subject, try the following books:

• The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia by Tim Tzouliadis

• They Took My Father: Finnish Americans in Stalin’s Russia by Mayme Sevander

• Karelia – a Finnish-American Couple in Stalin’s Russia by Anita Middleton

• Soviet Karelia: Politics, Planning and Terror in Stalin’s Russia, 1920-1939 by Nick Baron

Returning now to Edvard Gylling any explanation of Karelian Fever must begin with the life and career of Edvard Gylling, whose life can be divided into two halves. He was born in Kuopio, Finland in 1881 and up to June 1918 he resided in Finland. He grew up in a prosperous middle class family and became steeped in Finnish patriotism and Finnish cultural identity early in life. Gylling grew up in a family of women, his mother and sisters raised him as his father was often away on assignment for the Finnish state railway. On the family estate he learned his love for the countryside and became aware of the poverty that then afflicted so many in rural Finland. Gylling entered the University.of Helsinki in 1900 at the height of Russification under the hated Russian Governor General Bobrikov. He joined the Old Finn Party, believing, like other members of that party that conciliation toward the Russian authorities would encourage Bobrikov to mitigate his policies. Gylling won a scholarship to study in Germany for 6 months in 1904. He returned to Finland to find his homeland, the Grand Duchy of Finland, in a state of revolution. Gyliing had been exposed to socialist ideas in Germany and on his return he quickly joined the Finnish Social Democratic Party.

In 1906 Gylling was engaged to Fanny Achren. Both had been raised in central Finland and had a strong love for rural Finland. Edvard and Fanny were married on June 14, 1906. Gylling would be executed on their 32nd wedding anniversary by the Soviet regime as a bourgeois nationalist. His wife’s execution would follow shortly thereafter.

Starting from 1905, Gylling became prominent in the Finnish Social Democratic Party. He entered Parliament and became the party’s expert on agrarian matters. He also continued his academic career, writing his doctoral dissertation in 1909 and joining the faculty of the University of Helsinki in 1911. Gylling became a pioneer in the application of statistical methods to historical research and also became the official demographer of the city of Helsinki, conducting a census for the capital and for Finland as a whole. Such works are still widely consulted. Gylling’s publications in the first decade of the 20th century concerned the sorry plight of the Finnish crofters who were emigrating to the U.S. in large numbers. He also wrote about the exploited state of the Finnish peasantry when Finland had been a Swedish province. Gylling addressed the Finnish Crofter’s Association and drafted the Agrarian Program for the Finnish Social Democratic Party. His work on agrarian issues and his statistical research made him acutely aware of how serious were Finland’s demographic losses, primarily to the U.S., in the period 1894-1914.

Sosialistinen Aikalislehti was Finland’s first Social Democratic journal, for which Gylling served as editor in chief from 1906-1908. He was a prominent member of the SD party but also decidedly a moderate and a non-Marxist who wanted to work in parliament via coalitions with bourgois parties. With the Russian revolution of 1917, Gylling sought first and foremost autonomy for Finland if not outright independence. The Provisional Government in Russia refused to grant Finland independence but the Bolsheviks did in December 1917. Despite Gylling’s efforts at mediation between his own countrymen, civil war broke out between radical socialists and members of the working class opposing the large landowners and the middle class. Gylling deplored the conflict, seeing that it would only compound the demographic losses already incurred from emigration. In whatever he did Gylling found a unifying principle in Finnish nationalism. He deplored the emigration from Finland of the early 20th century just as he deplored the Finnish civil war. Both phenomena undermined the demographic stability of Finland. In politics Gylling was committed to compromise and negotiation and believed that even the most contradictory principles could be reconciled. He very reluctantly accepted the appointment as Member of the Revolutionary Government and Minister Plenipteniary for Finances and was the last high-ranking member of the Red government to leave Finland, doing so in May 1918. The victorious White government refused his offer to negotiate, and put a price on his head and as a result, Gylling, disguised as a woman, escaped to Stockholm where he spent the next two years of his life, from 1918-1920.

Gylling spent two years in Stockholm before receiving permission from Lenin himself to head the new Karelian Workers’ Commune. In Stockholm Gylling had somewhat reluctantly joined the new Finnish Communist Party founded by his former school mate O.W. Kuusinen. Lenin wanted Soviet control over Karelia secured. Gylling wanted to create a Finnish homeland under the aegis of the new Bolshevik government. He negotiated from Lenin agreements on the use of the Finnish language and restrictions on the immigration of Russians to Kareliaand in the process transformed himself from a prominent Finnish Social Democrat to an important Soviet official as the Permanent Chairman of the Karelian Council of People’s Commissars. In the Soviet Union Gylling quickly became the most important political figure in Karelia. By 1923 he was Permanent Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars.

In a logging camp at Matrossa, about 35 kilometers north of Petrozavodsk, North American Finns lived in rough dormitories adorned with the usual posters of Lenin extolling Soviet power — as well as placards written in Finnish.

The road to power in Karelia had not been direct, however. From Stockholm in 1918, he had written Lenin of a plan to make Karelia, in the far northwest corner the new Russian Republic, a place of refuge for Red Finns fleeing the victorious Whites after the Finnish Civil War. Lenin was not interested, but in 1920 when Lenin sought to secure Soviet control of Karelia before negotiations that fall which would determine the Soviet northwest border, Gylling’s earlier proposal appeared useful. He invited Gylling to Moscow where the two conducted negotiations on Karelia’s future status. Lenin promised that Karelia would retain a Finnish character, and Russian immigration would be kept to a minimum. Gylling acquired a measure of budgetary autonomy for Karelia and made Finnish equal to the Russian language in official transactions. In fact, in schools and in official business as well as in record keeping, Finnish replaced Russian as the language of Karelia.

Karelia: A Finnish-American Couple in Stalin’s Russia 1934-1941

Gylling wrote an article in 1925 on his plans for the future development of Karelia, revealing his concept of Karelia as a distinctive region of the Soviet Union, geographically, geologically and economically bound to the Finno-Scandinavian plateau of which it was an integral part. For Gylling, Karelia’s proximity to Finland and its tradition as the place where the events of the Finnish national epoch, The Kalevala, had occurred were far more significant than Karelia’s position as a constituent part of the Soviet Union. Gylling maintained the Finnish character of Karelia through the 1920’s. With the imposition of Stalin’s First Five Year Plan in 1929, Russian in-migration in the form of a large, new work force would surely change the ethnic character of Karelia and do so dramatically. Gylling decided to recruit an ethnically Finnish work force in North America. He had seen the North American Finnish diaspora form earlier in the century. Since the 1920’s it had often sent aid to Karelia.

In late 1928 or early 1929, Gylling travelled to Moscow to argue for the continued ethnic and economic autonomy for Karelia despite pressures imposed by the First Five Year Plan calling for fast paced industrial development. Gylling feared that the high industrial targets would mean the recruitment of a Russian work force that would dilute the Finnish character of Karelia. K. Rovio, head of the Karelian Communist Party, also shared Gylling’s commitment to a Finnish Karelia. In March 1931 Gylling and other prominent figures from Karelia again travelled toMoscow to make a special case for the right to recruit workers from abroad. Gylling drafted the petition requesting permission to invite lumberjacks and others skilled in the timber industry to come to Karelia and assist in the exploitation of Karelia’s “green gold.” At the Sixteenth Party Congress held the summer before, Molotov had called for inviting foreign workers and experts to contribute to the Soviet Union’s industrial development as part of the First Five Year Plan. Gylling now built on Molotov’s suggestion (which came direct from Stalin) to plead for a foreign, i.e. Finnish work force for Karelia. Gylling knew that such a work force existed in North America. He had calculated the demographic losses as a historian and statistician in Finland and now he hoped to recruit that work force for Karelia in order to maintain Karelia’s Finnish character. He would conduct such recruitment under the protection of Molotov’s recent directive. In effect, Gylling would recruit the Finnish North American diaspora to his Finnish homeland of Karelia.

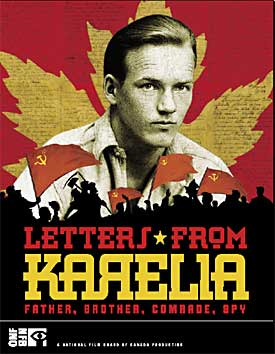

Letters from Karelia

However, by the end of the 1930’s Gylling and the North American Finns whom he recruited to live and work in Soviet Karelia would come to share the same fate. Gylling’s position in Karelia began to deteriorate in 1935. In early 1935 Gylling presented his production goals for Karelia in Moscow. He faced a hostile audience – Moscow was about to withdraw Karelia’s budgetary independence – which had been negotiated by Gylling in the early 1920’s. Important members of the Soviet government had begun to question the presence of so many North American Finns in Karelia, a border region next door to Finland, which was known to be hostile to the Soviet Union. In October 1935 he was forced to sign a denunciation of Finnish nationalism in Karelia, the very policy that he had earlier maintained with Moscow’s support. The following month he was recalled to Moscow where he joined Rovio, who had been sent there in August. Both men were replaced by Russians. Some of the Finnish Americans believed that Gylling had been promoted, not understanding that their own security was now as precarious as his. 1938 saw a dramatic turn in the fortunes of Gylling and the North American Finns whom he had recruited to Karelia. Gylling was arrested and shot in June 1938. As of July 1 1938 the Finnish language was outlawed and in Karelia Finnish newspapers and the Finnish radio station were shut down and Finnish books were burned.

Finnish-Americans in Petrozavodsk in the 1930s had a higher standard of living and were resented by their Russian neighbors.

Finnish Americans were now caught up in the holocaust that had begun in late 1936 in the rest of the Soviet Union. Many of those Finnish Americans who had joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union were arrested and executed. Most of the children were spared, that is anyone in the Finnish American community under age 21 by 1938. There were, however, tragic exceptions. A 16 year old Finnish American studying in the Petrozavodsk Conservatory was arrested and shot. The secret police as elsewhere had a quota of victims to meet. But in Karelia another element came in to play: circumstances had given those who envied the work ethic, prosperity, and higher standard of living of the Finnish Americans the opportunity to exact revenge. The newly appointed Russian administrators of Karelia now exacted a terrible toll on the North American Finns, who had worked so hard under Gyllings leadership.

Edvard Gylling was executed in June 1938. His wife, Fanny, was executed shortly thereafter. Of the almost 6,000 North American Finns who emigrated to Karelia, only 1,346 returned. Seven-hundred-ninety men and sixty-three women are known to have been executed during Stalins purges; many others died in labor camps of starvation during the Finnish-Russian War and during World War II. Some few escaped over the border to Finland or managed to return to North America by other means. Some still live in Karelia.

You can read some of the survivors stories here: http://www.d.umn.edu/~apogorel/karelia/survivors.html#ruth

Obviously, news and information trickled across the border, with refugees and escapers from the Soviet Union providing some information. It was not just a perceived threat that Finland faced. But from immediately after the end of the Civil War, with conflicts still endemic along the border and the Bolsheviks consolidating power, Finnish Conservatives responded by further improving their efforts to create a new and stable status quo within the country. Their program of creating a new Finland was predicated on the support of the paramilitary Suojeluskunta organization, the Civil Guards militia that soon became one of the key cornerstones of post-war Finnish society. “We must win the working class over to the side of our nation!” was one of the key propaganda slogans of the AKS (and the Army), and the chief aim of all civic activity in Finland during 1920s was indeed focused on improving the sense of Finnish national unity that had been tarnished by the Civil War. This was to be achieved by binding all segments of society together, “uprooting” Communism in the process. The Suojeluskunta and its associated female volunteer organization Lotta Svärd formed an umbrella group organizing various kinds of activity: training manuals, lectures, citizenship courses, national youth organizations (Sotilaspojat for boys and Pikkulotat for girls), sport clubs and actual military training and practices. The unifying theme in both organizations was the pessimistic worldview where an invasion from the East, from the Soviet Union, was not only probable, but imminent (a viewpoint that, given the activities on the Soviet side of the border and subsequent events, was certainly valid).

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2015 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2015 Alternative Finland