The Development of Fire Watching and it’s military applications within Finland

1928: Kulotus käynnissä metsässä. Kuva liittyy metsäylioppilaiden harjoitteluun Hyytiälän metsäasemalla. “Samoin” (alkuperäinen teksti), viittaa tekstiin “Metsä palaa!” / Prescribed burning under way in a forest by Forestry Students training at the Hyytiälä Forest Station. “Similarly,” (original text), the text refers to “the forest on fire!”

Sustainability has been the guideline for Finnish forest use even before the modern concept of “sustainable development” was coined. Forests were carefully managed and measures taken to prevent or reduce the impact of forest fires. Prior to the twentieth century however, such containment measures were localized and where they did occur, were on a small scale. Forest fires occurred on a regular basis and little could be done to identify and contain them barring efforts by local farmers, villagers and farm-laborers – efforts which were both manual and limited in the resources available to the immediate locality.

As a result of the work by forest professionals, from the turn of the century on there was a greater understanding of the economic impact of forest fires, and more and more in the way of national and private resources dedicated to reducing the effects. Early efforts generally focused on basic measures such as firebreaks and controlled or prescribed burning (burning off during the cooler months to reduce the amount of flammable material available for major forest fires, thereby decreasing the likelihood of more serious and hotter fires). Deliberate controlled burns early in the fire season substantially reduces the risks of stronger late summer forest fires.

Kulotusta / Prescribed Burning

Risk reduction is one thing, but while controlled burns reduced the risk and firebreaks helped to contain fires once started, the single best way to stop a forest fire once it has started is to spot it early and attack it at the source before it has the chance to spread. On a hot, dry, windy day a fire can be up and rolling within minutes after the first spark. On days like this, a fire needs to be sighted almost as soon as it starts and its location reported by the fastest means available. The race to beat a fire before it grows too big was the impetus behind the drive to find better, faster methods of detection.

As managed forestry grew in importance, and reforestation programs took place, fires multiplied. Land clearing, farming, lumbering, railroad construction, mining, prospecting, even hunting and fishing all added to the fire hazard. The State Forest Service and the large forestry companies took the first initiatives in the late nineteenth century, with regular forest fire patrols in managed forests. Fire rangers traveled alone or in pairs and were continually on the move, patrolling the forests for signs of fire. Terrain dictated the method of travel.

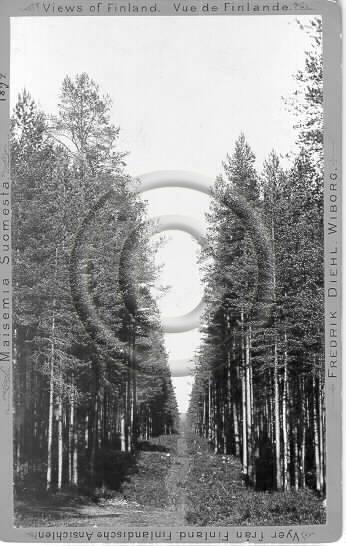

Männikön läpi kulkeva osastoraja, joka samalla toimi palokatuna / A Firebreak in the Pine Forest, which at the same time was the Border (with the USSR)

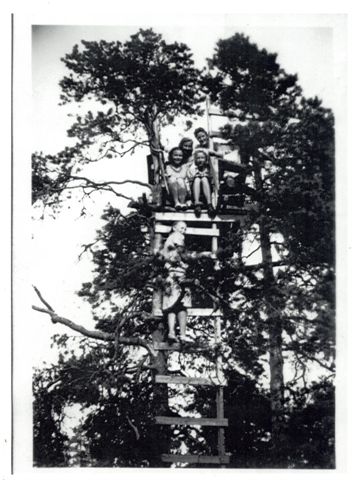

Fire rangers patrolled on foot through the bush, blazing and clearing their own trails. They scrambled up hills and climbed trees to get a better view. Sometimes they built a small platform or ‘crow’s nest’ in a tall tree to survey the area. When river or lake systems wound through the patrol area as they often did, rangers patrolled by boat – negotiating wind, weather, current, and portages.

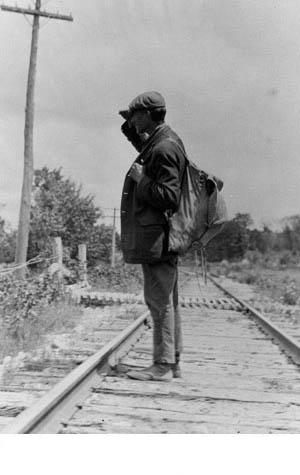

Railway Fire Patrol: As a rule, patrollers would ride one way and walk back. In addition to detecting and putting out fire, rangers worked to prevent fires through posters and public education.

Small steamboats were utilized for fire patrol on large bodies of water. Later, rangers patrolled in motorboats. Fire rangers also patrolled in horse-drawn buggies or on bicycles, if roads or trails or trail systems were good enough. Later as roads and technology improved, horseless carriages – cars, trucks, or motorcycles – were used to patrol, meaning the fire rangers could cover considerably more distance with a fraction of the effort. But no matter how a ranger patrolled his territory, one thing is certain. He knew his territory inside out. A fire ranger had to know the location of:

- High-value, high-risk areas: the places ready to explode into fire with one careless spark;

- Quickest routes to a fire: all the roads, trails, railroads and communication lines;

- Closest bodies of water: lakes, rivers, creeks, ponds and their proximity to timber stands, communities and other important areas;

- Fire fighters and equipment.

The grueling day-to-day patrols provided the ranger with the practical information he needed to find, fight, and prevent fire. With the expansion of the Rail Systen, fire rangers were hired to detect and put out fires caused by sparks from the stack and the ash pans of steam locomotives. By 1900, these rangers were stationed at intervals of some eight miles along the Finnish State Railway’s rail tracks. Their equipment consisted of a shovel, canvas pail and axe. Most of the patrolling was done on foot along the tracks by the railroad, but they could ride any train when necessary.

Rail patrols began well over one hundred years ago. The early steam locomotives were coal-fired. They spewed embers from the boiler, and sparks from the smokestack, igniting numerous fires along the right-of-ways. At first rangers patrolled sections of track on foot, equipped with a water pail and shovel. Later velocipedes and motorized speeders replaced foot patrols.

When a fire was found, the rangers job was to either put it out (if small) or report it (if too large to be dealt with single-handed). In putting out fires, the early forest rangers faced major obstacles. If the fire was still small, the fire ranger’s crude tools – shovel, axe, hoe and canvas water pail – might be enough to put it out. Hand tools had almost no impact on large fires and in these cases, getting fire fighting teams onto the fire to control it was the most urgent priority.

When the fire moved too fast for one man to handle, the ranger had to dash back to base, report the fire, round up a fire crew, and get back to the fire site. No matter how he traveled – on foot, by canoe, on horseback, or even by rail car – precious time was lost. Rangers on rail patrol had it easier. They patrolled the right-of-way along either side of the track, looking for fires caused by sparks from steam locomotives. The chances of catching fire in the early stages were better, but the fire ranger still had to hustle to beat the fire.

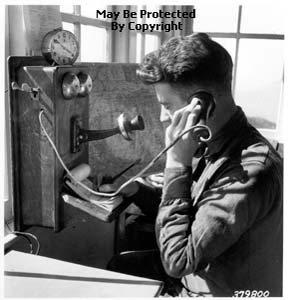

Phone-Tapping

Fire patrols were tests of strength and endurance. Rangers trudged over rugged terrain shouldering heavy packs, rowed and portaged boats, rode horseback over narrow forest trails, hand pumped railcars over miles of track, dug out fire break trenches, and hauled pail after pail of water to put out a fire. They coped with bugs, bad weather, accidents and wild animals. A fire ranger had to keep his bearings in the forest. He had to be able to use an axe to clear trails, set up camp, cook over an open fire, keep warm and dry, and treat any injuries he might suffer.

Gasoline-powered water pump – 1920’s

And he might be required to handle a boat, or ride horseback. Loggers and trappers were ideal candidates for fire ranging because they had the necessary forest skills – but rangers did not always fit the mould and “city-boys” sometimes took on the job quite successfully. In the late 1920’s, major changes in technology and in communications began to transform the role of the Forest Service’s fire rangers. When telephone lines were built into the forested areas, rangers could report a fire quickly if a phone line was located in the area. Or they could carry a portable phone, and tap into a telephone line if one was available. Telephone lines also led to a new source of detection – public reporting of forest fires.

Introduced in 1925 was a rather unique pump being demonstrated here that had no connected power source. Instead, this pump, operated by means of a belt drive off the wheel of a vehicle or motorcycle as shown here.

The use of motor vehicles meant patrols could cover far larger areas and also that fires could be responded to by teams of fire-fighters far more rapidly than in the past. The mid-1920’s also brought additions and improvements to fire fighting equipment. Previously only hand tools were available. Axes, shovels, brooms, crosscut saws and canvas pails were commonly used. Equipment to transport and utilize water was not yet invented or adapted to forest fire fighting. Gasoline powered pumps were one of the biggest changes during the period. There were several types purchased and used, but improvements were continuous, reliability was constantly improving and over the years the pumps themselves could move much larger volumes of water. The pumps themselves were used all year round – generally reserved for fire-fighting service over the summer months, they were used to pump water for ice roads in the winter logging season.

In 1924 the State Forest Service added the first piece of mechanized fire fighting equipment to its inventory. It was simply a heavy framed Ford truck with a gasoline-powered pump, four large barrels of water and several hundred feet of hose. The unit was in a rather loose sense self-contained. It was the forerunner of the modern day “slip-on unit” that would be developed years later.

The early fire rangers moved to higher ground whenever possible to increase their range of vision, scrambling up hilltops, mountaintops, and trees. Yet ground patrols were not good enough. Wildfires continued to inflict terrible economic losses and Fire lookouts evolved to meet the need for speedier, more effective fire detection. The first fire lookouts were generally used on a temporary basis. Fire Rangers might stay for a few days looking for fire. Then they moved on to continue their patrol.

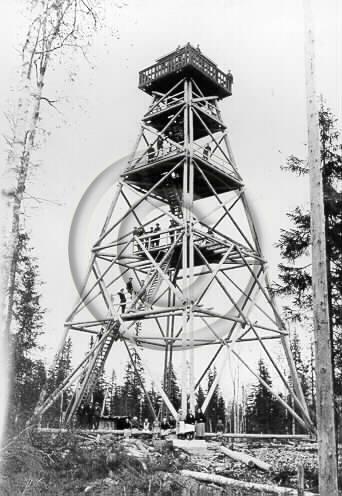

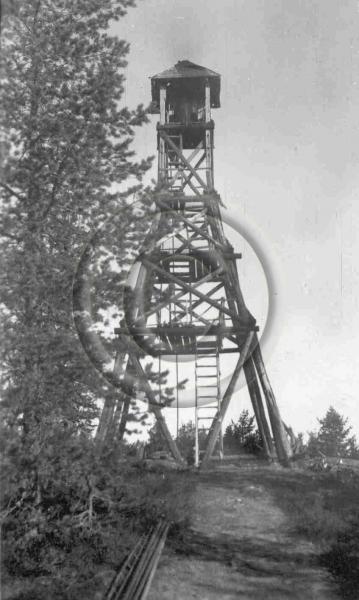

The late 1920’s saw the setting up of permanent Fire Watchtower systems which were built and then manned throughout the fire season. The first fire tower lookouts were wooden and erected at the turn of the century and after WW1. Most of these were about 35 ft. high. As the forest trees grew in height many of these were abandoned and 80 ft. towers were put up in their place in the 1920’s and 1930’s. The towers over time were grouped into Fire Districts. Towers were arranged over the years in specific spots to get the best view possible between each tower. Usually the best bet was to put a watch tower on top of a naturally high elevation like a sloping hill. State Forest Service or Forestry Company employees would then erect each in the span of two-three weeks. This was not a job for the faint-hearted or those afraid of heights.

The first fire lookouts evolved from whatever was at hand and could sometimes be quite ingenious, such as this old boat that had been grounded on the shore of a lake.

Towers were erected by State Forest Service or Forestry Company workers or contractors hired to do the job. Some pieces were were brought in by horse in the spring and often timber was cut on-site. It would take about 2 weeks to assemble from the ground up, starting at the cement block base. The top cabin or cupola was hoisted up piece-by-piece and bolted at the joints. The towers were certainly well engineered considering the fact that during high winds they would never shift although the odd one that wasn’t put together properly blew over, fortunately never with anyone inside.

Metsähallitus rakennuttaa palotornia, urakoitsija Aukusti Häyrynen. Kiiminki.; Aukusti Häyrynen / Metsähallitus (the State Forest Service) is building a fire tower. The contractor is Aukusti Häyrynen

A sharp eye, an alert attitude, and a detailed knowledge of the lookout area were the lookout observer’s most important tools – just as they are today. Once a smoke is spotted, the observer has to make very sure it is a fire. The smoke could be from an industrial smokestack – or it could be dust kicked up from behind a speeding truck along a gravel road. Back in the days of steam locomotives it might have come from the smoke-stacks of the train itself. All lookouts were equipped with fire finders, maps, binoculars to spot fire, and telephones to report fires. The fire finder, or alidade, is fitted over a map, to help the observer pinpoint the location of the fire.

If two or three fire lookouts report bearings for the same fire, the fire can be located accurately at the point where the bearings intersect. Binoculars are useful for scanning the horizon, although they are limited by their narrow field of vision. Most scanning is done with the naked eye. The observer reports the fire by telephone (in the early days lookouts were equipped with telephones only but Radios replaced the telephone when it proved to be a more reliable form of communication). In hilly areas, the towers were placed on the tops of hills but where the terrain was flat, toweres up to 30 meters (100 feet) in height literally “towered” above the trees.

Metsähallitus rakennuttaa palotornia, urakoitsija Aukusti Häyrynen. Kiiminki.; Aukusti Häyrynen / Metsähallitus (the State Forest Service) is building a fire tower. The contractor is Aukusti Häyrynen – II

Being a towerman was seasonal work starting May 1st and ending Oct. 1st depending on weather conditions. They worked long daylight hours, especially in the summer months when there was a high fire risk – when lookouts were staffed all day, every day. All lookouts were equipped with fire finders, maps, binoculars to spot fire, and telephones to report a fire. Most fires were located by using two towers giving the location of a fire on their map based on a 360 degree radius and with several towers pinpointing the direction to get the exact location of a fire.

The tool they used to spot a smoke was called an alidade. It was mounted on a circular table with a map of the area and a degree ring to plot fire direction. The tower was plotted exactly in the centre of this map. The observer reported the compass direction, distance and size of the fire to headquarters by ‘bush phone lines’ in the early years and by two-way radio in later years. If other towers reported the fire then a ‘fix’ could be plotted on the map at headquarters. At headquarters there was a larger map of their assigned area and every tower was marked by a point which was circled by a larger compass index.

Metsähallituksen rakennuttama 25 metriä korkea palotorni Yli-Kiimingin Patsaalassa Kuusamontien varressa.; Aukusti Häyrynen / Metsähallitus (the State Forest Service) building a 25 meters high fire tower – Kiiminki Patsaalassa Kuusamo road.; contractor Aukusti Häyrynen

Most towermen were supplied with live-in bunkhouses where they lived all summer. The towers were often so far back in the forest that commuting wasn’t an option. It goes without saying that being married or raising a family was not always a part of a towerman’s life during their tower tenures. Very occassionally however, wives and families accompanied the towerman. According to one wife of a towerman, “As far as I know I was the only wife who got to spend the summer at a fire tower. I cooked on a little wood stove and met visitors to the tower. We raised our son there in the summer and he climbed the 85 ft. tower by the age of one. We only got to go into town for food and pay once a month during a rainfall.” To “city-folks” it could seem like a romantic life, spending months at a time on the deep forests but paradoxically, the two most difficult aspects of the job were isolation and the height of the lookout towers.

The completed Fire Tower

Isolation was the most difficult aspect of the observer’s life – or paradoxically – the best part. It all depended on the person concerned. Frequently the fire observers lived and worked alone from May to October (with the exception of occasional visitors). Local trappers or loggers were considered ideal candidates for the job. They were used to the country, and accustomed to being alone. Quiet, introverted people who enjoyed months of solitude in the wilderness, were a natural fit – yet quite a variety of people took on the job and thrived – men and women – young and old, introverted and sociable. The fear of height was also a major difficulty for untried lookout observers. In forested country, the tower observer had to climb straight up a vertical ladder every morning, and down every evening. The prospect of climbing a 30-meter (100-foot) ladder could strike fear into the boldest heart. So can one look at the ground below before descending.

This photo gives a relative idea of the size and height of the towers

Towermen were expected to keep logbooks of their daily activities, and they also had guestbooks available for any adventurous folks who decided to climb to the top for the views. These were handed in to the head office in Helsinki at the end of the season. Men and women could climb up the tower if they wished, even when the towerman was on duty. It wasn’t an easy climb though. Going up was the easy part, but when one came to the opening of the cupola (the tower’s top housing) things weren’t so easy when one tried to manoeuver through the bottom opening. For many, the hardest part was the fear of going back down. The towerman would sometimes have to use a long rope to tie around the person’s waist to lower them back down to the ground.

The view from the Fire Tower – accommodation can be seen below

As with so many events in the 1930’s, there was a certain amount of serendipity in the hiring of a small number of women to work as forest fire lookouts. Even in the late 1920’s, the Lotta Svärd organisation already trained some members in Aerial Surveillance and it was perhaps pure chance that a small number of these were hired as forest fire lookouts. What was not chance was the proposal that resulted from one such member for the Lotta Svärd organisation to take on the responsibility for Aerial Surveillance for the entire country and train Lotta Svärd personnel to take on this role. The Fire Watch system provided a backbone on which this organisation could be built, utilizing the existing Fire Watchtowers and communications system and expanding this into areas not covered under the guise of improving forest fire monitoring.

Following the decision to adopt this proposal, Finland was divided into 52 Air Surveillance Areas, with each are having numerous air-surveillance posts (Ilmavalonta-Asema) and an Area Air Defence Centre (Ilmapuolustusaluekeskus or IPAK for short). All Ilmavalonta-Asema were to be manned by trained Lotta Svärd air-surveillance personnel, as were the area IPAK’s. Provision was made in the event of war for the rapid construction and linking in to the network of additional air-surveillance posts and sites were chosen and in many cases prepared and maintained through the last half of the 1930’s. This was a popular role for young women members of the Lotta Svärd, giving them an independent and important role in the country’s air defence and the air surveillance units were fully-staffed from the very start.

When the ever-watchful eye of the lookout discovers a spiral of smoke, he locates the fire by means of an alidade and protractor. Other lookouts do likewise. From the directions sighted, the watchman can locate the fire and dispatch forest fire fighters to the scene.

The headquarters of each Ilmapuolustusaluekeskus operated from a Control Centre, responsible for and controlling between 30 and 40 observation Posts each of which would be some 10 km to 20 km from its neighbour. In 1935, as mentioned previously, there were 52 Ilmapuolustusaluekeskus covering Finland, controlling in total some 1,920 posts – and with each post manned on average by some 8 Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta personnel, the entire organisation had a strength of approximately 20,000 personnel.

Accurate, concise and rapid reporting was emphasized. Aircraft recognition was a highly prized skill, with accurate identification of the wide range of aircraft in Finnish service as well as those used by the USSR being of crucial importance. Lotta Svärd Ilmavolonta personnel realised that there existed in this field a chronic skills deficiency, and the profile of aircraft recognition was raised within the ranks of the organisation. Aircraft recognition training material, consisting of aircraft silhouettes and other data, was introduced almost entirely under the auspices of the Lotta Svärd Ilmavolonta organisation and as this skill obtained official recognition, both the Maavoimat and Merivoimat requested training courses for their reservist personnel be conducted by the organisation.

An alidade or direction circle used by Finnish air surveillance observers at air raid warning posts during the Winter War and World War II. Photograph from the “Winter War – 70 years” exhibition in the Military Museum of Finland.

With the outbreak of war, trained Ilmavolonta personnel were in high demand as it was realized that despite such courses for Reservists, a shortage of well-trained personnel was leading to too many “friendly fire” instances where AA guns opened up on Ilmavoimat aircraft. Many Ilmavolonta volunteers were accordingly detached from rear-area posts and assigned to units near (and even in some cases on) the front-lines. These volunteers were generally replaced at the rear with teenage Lotta Svärd Ilmavolonta members who carried out the job with admirable dedication.

A fire guard reporting fire to headquarters by means of telephone. May 1931. The installation of “forest phone-lines” and telephones meant a vast improvement in the efficiency and coordination of responses to fires.

And of course, not all lookout personnel were men.

In 1932, following a Lotta Svärd proposal to the Ilmavoimat and an Air Defence Working Group initiative undertaken as a result, the formation of a Lotta Svärd Unit under Ilmavoimat command responsible for the visual detection, identification, tracking and reporting of aircraft over Finland was approved. Thus unit would be come known as the Air Surveillance Corps. Finland had no real experience in such an organisation, and a number of small study teams were sent abroad to investigate and report on the experience of other countries in WWI – primarily Britain, France and Germany. In the event, most was learnt from the British, who had to a certain extent maintained the experience and skills of the WWI Metropolitan Observation Service with their networks of observations posts and associated anti-aircraft hardware (although much of this had been decommissioned in 1920, by 1932 efforts were underway to resurrect the Observer Corps, it’s experience and expertise).

The British were cooperative in sharing their knowledge and expertise in this area with the Finns, and a great deal of useful information, both current and historical, was made available, together with numerous suggestion as to applicability for Finland. On the various teams returning to Finland, information was pooled and a working group rapidly set up an effective Air Surveillance infrastructure that would remain largely unchanged up until the end of the Second World War.

An improvised Observation Post high in a tree, together with the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta Spotter Team responsible for manning the position, Summer 1938

Each Observation Post was to be manned by a Lotta Svärd Sergeant and six other personnel. Through the 1930’s the number of air surveillance posts continually increased until by 1936 there was a continuous thick belt of observation posts along the southern borders, along the coast of the Gulf of Finland and throughout the coastal archipelago. A rather thinner belt stretched northwards long the Gulf of Bothnia. The interior of the country was also well-covered in the south but thinned somewhat in the North, with only scattered coverage in Lapland. At the end of September 1938 the political crisis which culminated in the Munich Agreement had led to the Air Surveillance Corps being mobilised for a period of one week. This single act proved to be invaluable as it highlighted a number of organisational and technical shortcomings, and provided the impetus for the development of solutions to resolve these. A series of exercises held throughout 1939 provided opportunities for the fine tuning of improvements made to command and control functions.

Operational procedures would continue to evolve throughout the war, a process facilitated by the enthusiasm, dedication and professionalism which Lotta Svärd volunteer members, coming from every walk of life, brought with them to the Corps. High quality Merivoimat-issue binoculars were issued to observers, whose observation posts in the country areas usually consisted of nothing more than a wooden tower or a platform hidden in the top of a tree, with a telecommunications link with a control centre, often via a manual switchboard at local telephone exchange. In urban areas, observation posts were usually located on the rooftops of public buildings and factories and were often substantial brick built structures, protected by sandbags, which due to their often having being constructed by Air Surveillance Corps personnel themselves meant that no two posts were identical.

In order to monitor aircraft, observers used a simple but effective mechanical tracking device. Where the approximate height of an aircraft is known it becomes possible, by using a horizontal bearing and a vertical angle taken from a known point, to calculate the approximate position of that aircraft. Posts were equipped with a mechanical sighting device positioned over a post instrument plotter consisting of a map grid. After setting the instrument with the aircraft’s approximate height, the observer would align a sighting bar with the aircraft. This bar was mechanically connected to a vertical pointer which would indicate the approximate position of the aircraft on the map grid.

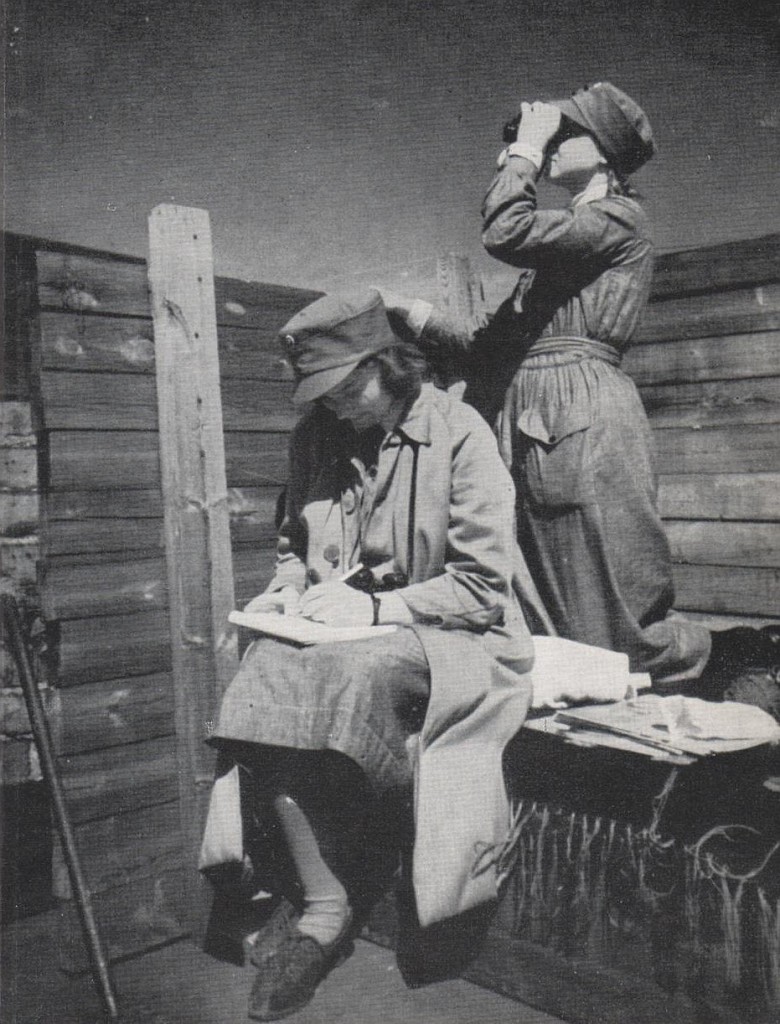

The mood turns more serious – Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta members on exercise following mobilization, Summer 1939

Observers would report the map coordinates, height, time, sector clock code and number of aircraft for each sighting to the aircraft Plotters located at the Ilmapuolustusaluekeskus. Positioned around a large table map, plotters would wear headsets to enable a constant communications link to be maintained with their allocated Cluster of posts, usually three in number.

The plotting table consisted of a large map with grid squares and posts being marked. Counters were placed on the map at the reported aircraft’s position, each counter indicating the height and number of aircraft, and a colour-coded system was used to indicated the time of observation in 5 minute segments. The table was surrounded by plotters, responsible for communicating with their allocated cluster of posts. Over time the track of aircraft could be traced, with the system of colour coding enabling the extrapolation of tracks and the removal of time expired (historical) data. From 1942, long-range boards were introduced into centre operations rooms, with Tellers communicating with neighbouring Ilmapuolustusaluekeskus groups in order to handover details of inbound and outbound aircraft tracks as they were plotted on this map.

Specific duties in the centre operations room included those undertaken by:

• Plotters – responsible for updating the plotting table and long range board

• Tellers – responsible for communicating with neighbouring ROC groups, Fighter Command Group and Sector controls, anti-aircraft batteries and searchlight units

• Alarm Controllers – responsible for liaising with the Police, the National Alert System, the Väestön Siviilisuojelu (or Civil Defence of Citizens) and with local industrial facilities

• Interrogator – responsible for liaising with ground controlled interception (GCI) radar units

• Duty Controller – together with an Assistant Duty Controller and Post Controller, responsible for supervising both the centre plotters and group observation posts .

On the outbreak of the Winter War, aerial surveillance was largely carried out by Ilmavalonta units throughout the country

While the early Finnish radar defence system was able to warn of enemy aircraft approaching some areas of southern Finland and the Gulf of Finland coast, once having crossed the coastline the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta organisation provided the only means of tracking their position. Throughout the Winter War and the remainder of the Second World War, the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta organisation continued to complement and at times replace the defensive radar system by undertaking all inland aircraft tracking and reporting functions, while the radar and radio-monitoring systems provided a predominantly coastal and southern border-oriented, long-range tracking and reporting system.

On 1 October 1939 Mobilisation Notices were issued to all members of the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta organisation. From 3 October 1939, observation posts and area control centres would be manned continuously until 12 May 1945, four days after VE Day and the network itself would be continually expanded so that by VE Day it covered Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Finnish-Polish controlled zones of Poland and Germany. During this period, the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta organisation was at full stretch operating 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, plotting enemy aircraft and passing this essential information to Ilmavoimat Fighter Command Groups and Air Defence Sector Controls. The organisation provided vital information which enabled timely air-raid warnings to be issued, thereby saving countless lives and forming a cornerstone of Major-General Somersalo’s air defence system. In December 1940, Somersalo would write: “It is important to note that at this time they (the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta organisation) constituted the whole means of tracking enemy raids once they had crossed the coastline or the border. Their work throughout was quite invaluable. Without it the air-raid warning systems could not have been operated and inland interceptions would rarely have been made.”

Observation Tower built in late-1939. Unlike the Fire Watchtowers, an attempt has been made to camoflauge this tower by constructing it around and through an existing tree.

Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta Spotter Team member on duty during the Winter War. She stands next to the directin finder.

At the height of the Winter War, January 1940: a Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta Spotter Team on watch. Very little moved in Finnish air space without the Ilmavalonta Spotter Teams identifying, reporting and tracking them.

Mobilization and War – mid-November 1939: A Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta Spotter Team about to leave for their Observation Post deep in the forests of Eastern Karelia. As the Maavoimat advanced into Soviet territory, more such teams would be dispersed through the occupied areas to build and staff isolated observation posts. All such Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta Spotter Teams were at risk from Soviet partisan activity and Red Army stragglers who had been cut-off by the Maavoimat’s advance and were thus heavily armed. Such teams in the occupied areas were usually larger for security purposes than the spotter teams within Finland itself.

Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta members on exercise, Summer 1938

And Observers were not without other “protection.” Trained war-dogs often accompanied Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta Teams into isolated positions. Friendly to their “pack,” they provided an excellent early-warning system and were also trained to fight.

A young Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta Spotter Team on the job – August 1940: as the war continued and demands on manpower increased, large numbers of teenage-girl members of the Lotta Svärd were called on to fill Svärd Ilmavalonta Spotter Team positions – a role they filled capably and with superb dedication. Over 1939 and 1940, Finland brought a whole new meaning to the term “Total War” with the largest proportion of her population under arms of any country in WW2.

In 1943 and 1944, during preparations for the invasion of Estonia, a request for volunteers from within the ranks of the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta organisation produced 1,094 highly qualified candidates, from which 796 were selected to perform aircraft recognition duties as Seaborne Observers. These Seaborne Observers undertook specialist training prior to being temporarily seconded to the Meroivimat. The Seaborne Observers continued to wear their Lotta Svärd uniform, but in addition wore a “SEABORNE” shoulder flash and Merivoimat brassard. During the E-day landings, two Seaborne Observers were allocated to all participating Meroivoimat vessels and Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships. The Seaborne Observers assumed control of each ship’s anti aircraft batteries with the intention of reducing the incidence of friendly fire between Merivoimat vessels and allied aircraft.

The success of the Seaborne Observers in undertaking this role can be measured by a signal sent by Major-General Somersalo after the landings had been successfully accomplished, who stated that: “The general impression amongst the Fighter wings, covering our land and naval forces over and off the beach-head, appears to be that in the majority of cases the fire has come from allied forces on shore and not from our ships. Indeed I personally have yet to hear a single pilot report that a Merivoimat or merchant vessel had opened fire on him.”

During the landings a total of two Seaborne Observers lost their lives, several more were injured and twenty two survived their ships being sunk. The deployment of Seaborne Observers was regarded as an unqualified success and in recognition for their contribution to the success of the landings, Marshal Mannerheim approved the permanent wearing of the SEABORNE shoulder flash on the uniforms of those individuals who had taken part.

An Area Air Defence Centre (Ilmapuolustusaluekeskus): Tellers on the balcony overlook the plotting table and vertical long-range handover board. At the end of the balcony a Leading Observer acts as Post Controller. Note that Area Air Defence Centre’s included a small number of Ilmavoimat personnel.

The Lotta Svärd Aerial Surveillance Badge – worn by all members who had passed the air surveillance course. This was no sinecure, training was tough and Observers were expected to identify all types of aircraft accurately, as well as being able to determine speed, height and direction.

Following the invasion, the head of Ilmavoimat Fighter Command wrote a message which was circulated to all Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta personnel: “I have read reports from both pilots and naval officers regarding the Seaborne volunteers on board naval and merchant vessels during recent operations. All reports agree that the Seaborne Ilmavolonta volunteers have more than fulfilled their duties and have undoubtedly saved many of our aircraft from being engaged by our ships guns. I should be grateful if you would please convey to all ranks of the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta organisation, and in particular to the Seaborne observers themselves, how grateful I, and all pilots in the Expeditionary Air Force, are for their assistance, which has contributed in no small measure to the safety of our own aircraft, and also to the efficient protection of the ships at sea. The work of the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta organisation is quite often unjustly overlooked, and receives little recognition, and I therefore wish that the service they rendered on this occasion be as widely advertised as possible, and all units of the Air Defence of Finland are therefore to be informed of the success of this latest venture of the Lotta Svärd Ilmavalonta organisation.”

As the liberation of the Baltic States by Finnish and Allied forces proceeded, the Lotta Svärd organisation was heavily involved in relief efforts in the liberated territories of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and finally of Germany and Denmark. Counterpart organisations to the Lotta Svärd were rapidly setup, members recruited and training undertaken. In this way the Lotta Svärd organisation, including Ilmavalonta units, replicated itself as far south as Poland by late 1945. Initially all such organisations were under Finnish command, but after the Second World War ended, they were transferred to fall under their own countries military organisations. Polish and Finnish military units would however remain in the territories of the four Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and East Prussia) until into the early 1990`s.

Table of Contents

Previous Page:

Next Page:

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2015 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2015 Alternative Finland