Finland – The Third Path – an Alternative History

“In peace prepare for war, in war prepare for peace. The art of war is of vital importance to the state. It is matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin. Hence under no circumstances can it be neglected.” Sun Tzu. The Art of War.

The decade of the 1930’s was a time of growing tension for the smaller states of Eastern Europe, Finland among them. Since the end of the First World War they had enjoyed an independence which most of them had not known for centuries, but from the early 1930’s this independence was increasingly threatened by the growing power of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Instead of combining for self-defence as they might have, the eastern european states were bitterly divided. The Munich crisis and the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia showed how little reliance could be placed on the Western democracies, whose power to intervene militarily in Eastern Europe was negligible in any case. In effect this left the smaller East European states with little alternative but to become clients of either Nazi Germany or Russia. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 took away even this choice for Poland and a little later for the small Baltic States.

Over the 1920’s and 1930’s, newly independent countries such as Poland and Czechoslovakia had built up respectable armed forces. In the end, this did neither country any good. In Czechoslovakia’s case, despite a sizable and well-equipped military, the population was divided and the government lacked the political will to fight when the country was isolated and abandoned by France and Britain. In the case of Poland, the country fought, but with an obsolete military doctrine and flawed strategy. Caught between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, they were defeated in detail. States such as Hungary and Romania ended up siding with Germany, while those states such as Yugoslavia and Greece that opposed the Germans were decisively defeated. Bulgaria remained neutral but in the end, was taken over by the Soviet Union in any case.

Finland consciously chose a third path. Finnish plans were the diametrical opposite of those states (such as Czechoslovakia) which emphasized the need to avoid provocation in a tense bilateral situation. Finnish planning called for an aggressive general mobilization in the face of any overt and substantial threat, after which the Armed Forces would be kept at full readiness until the crisis was resolved or fighting broke out. Finland would be defended to the end with no surrender contemplated or authorised. Indeed, Standing Orders for all military units were that in the event Finland was attacked, no surrender would be contemplated or ordered, and any communications purporting to be from the Government and ordering surrender should be ignored and the carriers of such purported orders were to be summarily executed.

However, the Government and the Military Command were also under no illusions about the enemy Finland faced. The only conceivable threat to Finland was, despite the platitudes and maundering of some on the Left, the Soviet Union. And Finland’s military commanders were well aware that in the face of a determined assault from the Soviet Union, they would be defeated by sheer weight of numbers. Finland did however have a number of defensive advantages, primarily the terrain. Finland was NOT Europe, and Finnish terrain was NOT the flat european plains that the armies of Germany, France and the USSR were equipped and trained to fight on. Finland was a land of dense and featureless (to an outsider) forests, lakes, rivers and swamps with few railways, limited roads and many natural obstacles. Finnish defensive strategy evolved through the 1920’s and 1930’s to take advantage of these features.

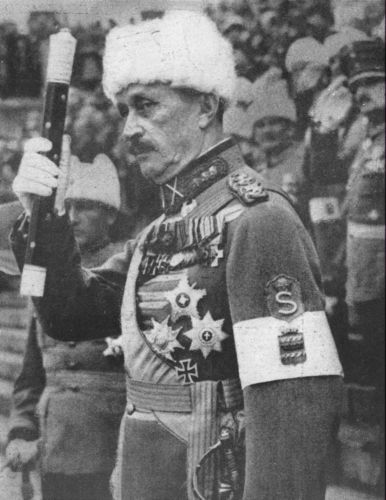

Marshal Mannerheim – a military commander of true genius

From 1931 on, the Finnish Government placed an increasingly strong emphasis on Defense spending, and combined this with the good fortune to possess a military commander of true genius (Marshal Mannerheim, who ranks as one of perhaps a dozen of the greatest “defensive” military commanders of all time) and an innovative approach, born out of a strong desire to remain independent and free at all costs, applied to both military organisation, tactics and training as well as to the development of effective weapons and the creation of a small but inspired military-industrial complex. Much of this was made possible by a combination of the rapid economic growth enjoyed by Finland throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s, together with the willingness of all major political parties to ensure defence was adequately funded (even at the expense of reduced spending on social services and the taking out of large loans from the USA, France and Britain to finance the purchase of armaments). The continued purchasing of Annual Defence Bonds from 1931 on by both the public at large and by Finnish businesses of all sizes also made a major contribution to defence spending. At the same time, through the 1930’s the wounds of the Finnish Civil War were, if not completely healed, at least addressed, largely through the efforts of Mannerheim and the leader of the Social Democrat Party, Vaino Tanner – unlikely allies but both men with the interests of Finland at heart.

Finland entered the European Conflict of 1939-45 with a population that was socially highly cohesive and nationalist in outlook, an Army that was large in comparison to the small population of the country, effectively organised into small and highly mobile Infantry Regiments with a very high ratio of firepower to men and well-equipped with modern (and in some cases innovative) weapons and ammunition, a Navy that was both capable and equipped to fulfill it’s limited strategic objectives and an Air Force that, while small, was well-equipped and highly trained. Combined with this were very aggressive (and in many cases innovative) training, innovative tactics geared to the countries difficult terrain and climate, a command structure geared as much as possible to individual initiative, the preparation of numerous in-depth defensive positions throughout the Karelian Isthmus and elsewhere along the countries borders and a willingness to fight to the death in defence of their country.

Faced with increasing pressure from the Soviet Union in the late 1930’s, Finland responded with a dramatic increase in defence spending over 1938 and 1939 (reaching 30% of the State Budget in 1938 and 45% in 1939, in addition to a thirty million US Dollar loan from the United States in early 1939 – which followed an earlier loan for a lesser amount in late 1937 – and the equivalent of a fifteen million US dollar loan from France, all of which was used for the purchase of military equipment). In negotiations that took place prior to the Winter War, Finnish negotiators pointedly assured the USSR that Finland could defend itself from external threats such as an attack by Germany and would not permit the USSR to be attacked through Finnish territory. Stalin, in his desire to best Hitler at his own game, ignored (indeed, laughed) at Finnish assurances and proceeded to threaten Finland with war if the requested territory was not ceded. The Finnish Government did not precisely take these threats lightly (defence spending reflected this) but many on the Left of the political spectrum believed that with Finland’s growing economic links and trade in oil and heavy industrial machinery (including merchant ships and locomotives) with the USSR, the Soviet position was largely verbal. The dismemberment of Poland between Germany and the USSR in September 1939 brought a dose of reality to many, but Stalin’s attack on Finland was still a shocking surprise to many of these politicians of the Finnish Left.

In attacking Finland, Stalin did not ignore the assessments of Soviet Intelligence, which were surprisingly accurate in terms of assessment of numbers of men and weapons. The size of the Soviet forces assembled to attack Finland were proof of that – one million soldiers, two thousand tanks, two thousand fighters and bombers. It was an overwhelming force. On paper. However, the Soviet assessment that Finnish workers would rise up and welcome the “Soviet Liberators” was surprisingly inaccurate. Stalin and the Soviet political leadership expected a result similar in many ways to their occupation of eastern Poland (or indeed, Germany’s invasion of Poland). Instead, the attack on Finland proved a military and political disaster for the Soviet Union, and one that would have major ramifications on the course of the Second World War. At a personal level, it also led to the death of Stalin and most of the Politburo in the surprise Finnish bomber strike on the Kremlin that broke the stalemate of Summer 1940, a strike made overwhelmingly successful through the annihilating effect of the recently developed and secretly but successfully trialed Finnish-developed fuel-air bomb.

At a strategic level, the war had a number of outcomes, among them the internal change in leadership within the USSR in August 1940 as a result of Stalin’s death. The Triumvirate that assumed power in the confusion and chaos surrounding the death of Stalin and much of the senior Soviet political leadership rapidly concluded first a Truce and then a Peace Treaty with Finland. A further outcome was that Hitler discounted the ability of the Soviet Armed Forces and as a result later launched Barbarossa on assumptions that would in the event prove to be somewhat outdated. Later ramifications including Finland facing down Germany, permitting supplies across the border into Leningrad during the famous Siege and thus ensuring that mass starvation was avoided.

There were other, secondary outcomes, but for Finland, the outcome of the Winter War was successful in that Finland remained independent and did not cede any territory to the USSR (indeed, the USSR ceded parts of White Karelia to Finland and also transferred all Finnish-speaking peoples from Soviet Karelia and Ingria, included the estimated one hundred thousand Karelians and Ingrians who had been deported to Siberia, Kazakhstan and the Caucasus in the Purges of the late late 1930’s). Victory was achieved at the cost of some forty five thousand Finnish dead and seventy thousand wounded – approximately 1 in 5 of the Finnish soldiers who fought in the Winter War, a tremendously high price from a country with a population of only three and a half million. But in the estimation of all Finns, the price of an independent and free Finland was worth the payment.

Oi kallis Suomenmaa (O Precious Finland): the price of an independent and free Finland was worth the payment.

That the 1939-1940 Russo-Finnish War ended as a victory for Finland despite the overwhelming numerical and material odds faced by the Finns is a tribute both to Finland’s military leader through the Second World War (and first post-war President) and to Finland’s political leaders of the last half of the 1920’s and through the 1930’s. These leaders foresaw the threat that Finland faced and overcame many obstacles, both political and financial, to ensure that Finland’s military forces were equipped and trained for the conflict they hoped would not come. But come the conflict did, and Finland’s military were not found wanting. They triumphed over uncountable odds, won victories that stunned and amazed the entire world, then signed a Peace Treaty that gave back almost everything they had won in return for Peace.

Finland was involved in other theaters of the Second World War – the Finnish occupation of Northern Norway in response to the German invasion being an example, and for long maintained an uneasy neutrality, trading nickel from Petsamo and iron from Tornio to Germany via Sweden as well as leasing merchant ships to the British, providing access for supplies to besieged Leningrad (although there was no love for the Russians, it must be said). And then there were the subsequent events that brought a reluctant Finland into the Second World War as one of the Allies, fighting alongside the Russian Army, liberating Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and driving into Poland and then Germany in a race with the Russians. One of the better known battles involving Finnish forces in this later involvement was the famous airborne drop of the Finnish Airborne Jaeger Division, the British 1st Airborne Division under Major-General Roy Urquhart and the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade under Brigadier General Stanisław Sosabowski, into Warsaw to fight alongside the Polish Home Army in the Warsaw Rising while the Finnish 21st Pansaaridivisioona spearheaded the combined Finnish-Polish-Estonian-British-US Divisions struggling to breakthrough and relieve the siege.

How Finland achieved these successes (albeit at a high cost) is a long and involved story, starting in the mid 1920’s, shortly after Independence……….

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland