Hotel Kämp: a History of one of Helsinki’s most famous Hotels

Built originally in 1887 by the restaurateur Carl Kämp (1848-1889) as a luxurious hotel, and designed by the architect Theodor Höijer (1843-1910), Hotel Kämp is in an ideal location in central Helsinki. At the time of its opening and into the late 1940’s, the hotel added a contemporary continental – for most local observers a Parisian – touch to Helsinki. Guests of the city’s leading hotels, the Seurahuone and the Kämp, arriving by train or boat, were fetched in an omnibus from the train station or the harbor. During the decades immediately after the Hotel Kämp was built, modern transnational travel emerged, with luxury hotels being built near train stations. Georges Nackelmacker developed his network of Wagon-lits luxury trains around Europe. The increased mobility stimulated commerce and economic growth. The phenomenon of Grand Tour cultural tourism grew more popular and at the same time was expanded by growing numbers of common tourists as well as by business travelers.

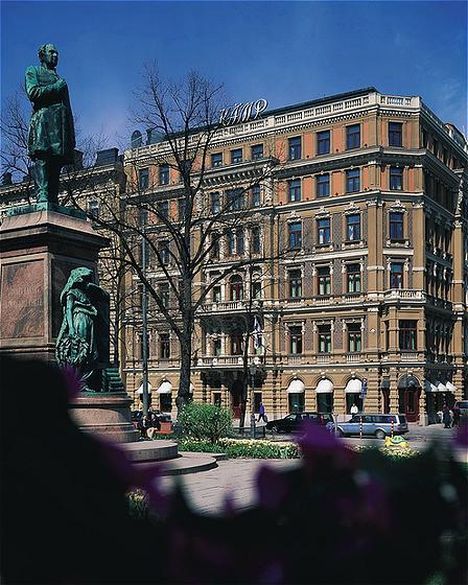

Hotel Kämp, Helsinki

It became fashionable for the bourgeois to live in the city centers, where new waves of urbanization reshaped many European capitals. Modeled after the Champs-Elysées in Paris or the Nevsky Prospekt in St Petersburg, Helsinki developed its Southern and Northern Esplanades, separated by an elegant park. The Hotel Kämp is situated on the Northern side or Pohjoisesplanadi, which was paved in 1891 and where people had the right to construct stone buildings, whereas the Southern side or Eteläesplanadi was reserved for wooden housing, the street having previously belonged to a suburb. In 1832, on the site of the future Hotel Kämp, a wooden house was built according to designs by Helsinki’s main architect, Carl Ludwig Engel of Berlin. In 1812, Tsar Alexander I had made Helsinki Finland’s capital. After a fire had destroyed large parts of Helsinki, the redesigning of the city was assigned to Engel who, previously, had worked on city designs and building architecture for Tallinn and St. Petersburg. In the 1840s, a bakery and warehouses were built on the site.

In 1874, the goldsmith Ekholm had bought the houses on the site but they were in such a bad shape that he was ordered to demolish one of them. As a result, he was no doubt glad to sell them both in 1883 to the restaurateur Carl Kämp. Born in a village in the parish of Helsinki in 1848, as a young man, the restaurateur Carl Kämp moved to the capital to work in restaurants and hotels, including Seurahuone (Societetshuset in Swedish). In 1872 he set up his first own restaurant Oopperakellari, which quickly gained a considerable reputation. He married a German woman, Maira Dorothea (née Moss), and they had two children. Helsinki was at this stage rapidly modernizing – in 1882, a private telephone network had been created and, in 1884, the first light bulbs had been lit in Helsinki. During these exciting times, Carl Kämp set his ambition on building a grand hotel. He had a budget of one million gold Marks, including a separate state loan and a construction loan from the Imperial State. 180,000 Marks were reserved to buy the site, 690,000 Marks for the construction and 130,000 Marks for the decoration.

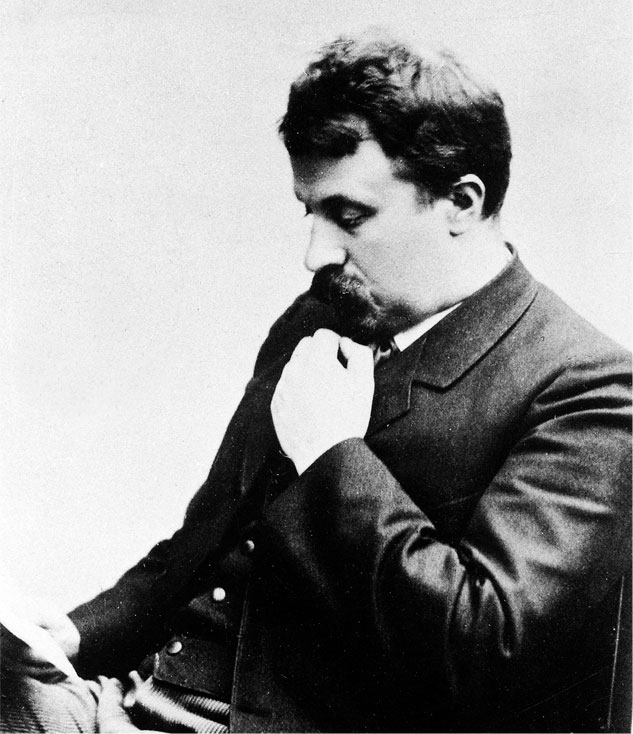

Architect Theodor Hoijer(1843-1910)

The preliminary blue prints for the hotel were completed in 1885 by the architect Theodor Höijer (1843-1910). Höijer had graduated from the Royal Academy in Stockholm and became the first architect in Finland to gain important private commissions. Among the notable public buildings designed and constructed by Höijer are the Finish National Gallery or Ateneum, the main fire station and the main library in Helsinki. He was active until 1905, when he became seriously ill. When Kämp’s project risked failing for financial reasons, the owner of the apartment block next door, the Municipal Councilor Frederik Wilhelm Grönquist (1838-1912), an orphan who had become a risk-taking self-made businessman, stepped in and bought the hotel’s site, offering Kämp a twenty-year lease.

The inauguration of Hotel Kämp took place on October 29, 1887 and it was officially opened to the public three days later. The Hotel had installed some of the first lifts in Finland. The interior was decorated by the Helsinki artist C. H. Carlsson. Bronze candelabras, Venetian chandeliers and crystal chandeliers from Berlin, which functioned partly with electricity, partly with gas as well as the staircase with railings cast in iron were other highlights of the Kämp. The luxury apartments and suites on the first floor were decorated with silk, the smoking salon was upholstered with yellow leather. The center of admiration was the giant mirror in the ballroom, which was lighted with 25 electric and 24 gas lights creating “a brightness never seen before”, “swimming in a sea of light”. The hotel also hosted a side office of the telegraph company.

During the years of economic and social development in the second half of the 19th century, in the age before mass communication, Hotel Kämp quickly became a political and cultural meeting point for an elite of Finns optimistic about the countries future. At the time, the Helsinki newspapers published a daily list of tourists who arrived in the capital. The Hotel Kämp consistently had the longest and most varied guest list. However, the generous and friendly Carl Kämp would not enjoy his success for long. He died from a heart attack only 2 years after the opening. His widow, Maria Kämp (Suite 512 is named after her), took over in a very professional manner, announcing the passing away of her husband on the front pages of Helsinki’s newspapers, underlining that the hotel would continue to operate without interruption. Maria was assisted in running the Kämp by her hotel manager, the German-born Karl König, a former actor who had previously run a German beer pub selling sausages and refreshments. The two could not manage a luxury hotel and quickly ran into financial difficulties which forced Maria to sell the Kämp to the newly established Ab Hotel Kämp company in 1890. Subsequently, the widow emigrated with her children, returning to live with her family in Sweden.

The new owners, three businessmen, who had paid 1,290,000 Marks, were unable to make the company profitable. On the verge of bankruptcy, it was taken over in 1892 by the experienced restaurateur Axel Gummesson, who had owned the Seurahuone Hotel of Oulu for several years. He hired a Swedish assistant manager, A. Lundbland. The domestic appliance shop on the ground floor moved out and the space was turned into the Kämp Café on December 21, 1889. The restaurant immediately began to flourish, and Hotel Kämp was saved. The hotel continued to attract Helsinki’s upper-class bourgeoisie as customers. The ground floor fine dining restaurant became known as the Lower House, later as the Bourse Café, because Gummesson and Lundbland sensed the opportunity to turn the Kämp into a meeting place for leading Finnish businessmen, who now had the opportunity to meet their foreign counterparts in an elegant setting. In addition, many Finnish businesses were run by German or Russian industrialists who appreciated the “continental” atmosphere.

Danish variety star,Dagmar Hansen

For instance the Russian Sinebrychoff and Kiseleff families started a beer-brewing business and the German Stockmann family built the leading department store. The Osberg’s, Wulff’s, Paulig’s, Knief’s, Schröder’s and Bargum’s were some of the other German families who were well-established in Helsinki and, by their visits to the Kämp, helped to insure the hotel’s success. The Kämp’s Upper House focused on night life and attracted Helsinki’s jeunesse dorée with its elegant contemporary design with a small dance floor and a clientele who could afford to buy expensive drinks. Hotel Kämp was also famous for entertainment. The management was the first to introduce female orchestras from Vienna to the audience. Hotel guests were especially fond of the American musical comedy singers Helma and Anna Nelson. Other performers at the hotel Kämp included the long-legged Danish variety star Dagmar Hansen, the black singer and comedian Geo Jackson, the Italian singing and music company Emilio Colombo, the “Überbrett singing and dancing artists,” Helge and Ingeborg Sanberg as well as many authentic – and some less authentic – Spanish flamenco dancers.

Although Tsar Alexander II proclaimed in 1863 that Finnish was to be a language equal to Swedish in matters concerning the Finnish people directly and the Finnish Theatre was inaugurated in Helsinki in 1873, Swedish remained the preferred language of the educated. With the rising political aspirations of the Finns, a language dispute erupted especially at the beginning of the 20th century, with politics aggravating the linguistic issues. From 1880 to 1890, The Finnish Club, originally a reading and conversation club, met at a rented apartment at the Kämp. Slowly, the club was transformed into a political “Club for Diet members”, discussing politics in a lively atmosphere. Therefore, at the Hotel Kämp were born the ideas of a Finnish-speaking national theatre, a national bank, a life insurance, a savings bank and a Finnish publishing house. In 1898, the Finnish writers Juhani Aho (Suite 812 is named after him) and Kalle Kajander together with the painter Pekka Halonen were refused entrance to the Kämp, apparently due to inappropriate clothing. The incident caused an uproar amongst the pro-Finnish community, which only calmed down when the doorman made a written apology to Aho.

Juhani Aho, Finnish author and journalist

Aho’s literary output was wide-ranging since he pursued different styles as time passed – he started as a realist and his first novel “Rautatie” (Railroad, 1884), red one of his main works, is from this period. Later he moved towards neoromanticism with his novels “Panu” and “Kevät ja takatalvi” as well as Juha, his most famous work which has been twice adapted an opera, and filmed four times, most recently in 1999 by Aki Kaurismäki. In addition to his novels Aho wrote a number of short stories in a distinct style, called “lastuja” (“splinters”). Their topics varied from political allegories to depictions of everyday life. The first and most famous of the short stories is “When Father Brought Home the Lamp”, depicting the effect of technical innovation on people living in the countryside. Nowadays the title is a Finnish saying used when something related to new technology is introduced. Aho was one of the founders of Päivälehti, the predecessor of the biggest newspaper in Finland today, Helsingin Sanomat.

In 1900, a new company, AB Hotel Restaurant, was founded to run Hotel Kämp. The capital of 240,000 Mark was equally shared by Gummesson, Lundbland and the property owner Grönquist. By 1910, Lundblad – an able and popular man – had acquired all the shares and become the real director and manager of the hotel and restaurant until the autumn of 1918. Among the other famous groups meeting at Hotel Kämp was the table of a group of architects including Eliel Saarinen, Armas Lindgren, Bertel Jung, Lars Sonck and Nils Wasastjerna. Another group met at the “Lemon Table” formed in the 1910s around the unmarried, wealthy Councilor John Grönlund. Unwritten laws ruled the tables, which could not be approached by acquaintances sitting at other tables. Women were rarely seen in these rounds, according to the unwritten rule “when a man wants to wine and dine, let erotic distraction stay out of it.”

The Kämp Bar: This was a popular meeting spot in the Helsinki of yesteryear

Members of a new, liberal front called Young Finns striving for a Finnish National State also met at the Hotel Kämp. Some 28 writers and 12 illustrators belonging to this Finnish nationalist movement, influenced by Europe’s modernizing movements, published Suomi 19:llä Vuosisadalla, an opus presenting Finland as a modest and small country of the far North, a bridge between East and West, a vanguard of culture, urging her contribution to Europe’s civilization. Probably the hotel’s most famous frequent guest was the composer Janne ‘Jean’ Sibelius (1865-1957). Incidentally, in 2003 the movie director Timo Kovusalo chose the Kämp as one of the settings for his film Sibelius, starring Martti Suosalo as the composer. Sibelius was part of the circle of Young Finns including the artist Arvid Järnefelt and the editor-in-chief of the Young Finns organ, the Finnish-language newspaper Päivälehti (1890, or Helsingin Sanomat from 1904 onwards), who spent so-called “Symposium” evenings at the restaurant of the Hotel Kämp, discussing the evolution of Finnish national culture, especially from the autumn of 1892 until 1895.

The premiere of Sibelius’ symphony Kullervo in 1892 expressed the nationalist ambitions of the Young Finns, for whom music was a central part of their cultural movement. Incidentally, the composer and conductor Robert Kajanus (1856-1933), who founded the Helsinki Orchestra in 1882, was another eminent member of the Symposium at the Hotel Kämp. After concerts, Sibelius, Kajanus and Järnefelt regularly met at Kämp’s Lower House for discussions with Swedish punch, Benedictine liqueur and cigars, accompanied by musical improvisations by the artists present. Sibelius, who focused on teaching at the university, never missed an evening. Apart from a few exceptions, women did not take part in these Symposium sessions. A fact less appreciated by his wife. Sibelius described the times at the Hotel Kämp as follows: “The waves of our conversations rose sky-high. We reflected on everything from earth to heaven, ideas sparkled, problems got inflamed, but always in a positive, liberating spirit. We had the need of ploughing the earth for new ideas in every branch. Those evenings the Symposium gave me a lot at a time when I would have been more or less alone.”

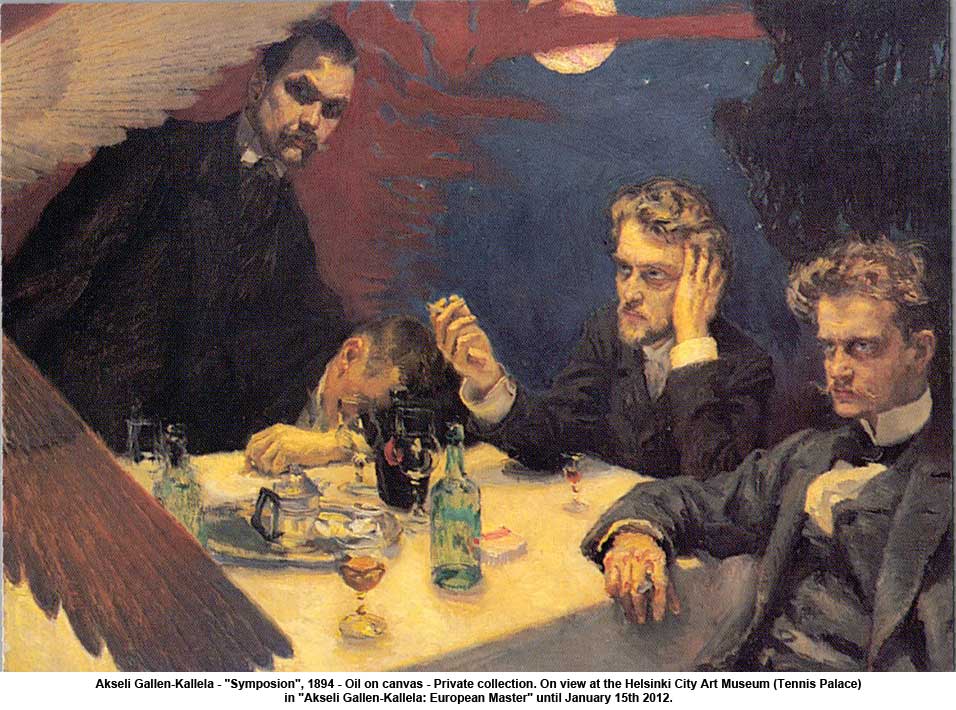

In 1894 Akseli Gallen-Kallela painted “The Symposium” – the name of the group of Finnish artists in which Gallen-Kallela was a leading figure. The artist himself can be seen in the upper left corner of the painting. He also portrayed his friends, Oskar Merikanto, Robert Kajanus, and Jean Sibelius in the midst of heavy drinking.The theme was inspired by an evening at the Hotel Kämp

The evenings of the Symposium group at the Hotel Kämp are immortalized by the painter Aleksi Gallén-Kallela (1865-1931), a spiritual soul mate of Sibelius, in “Symposium” or “Problem” (1894), as the painting was initially called, showing the organist and composer Oskar Merikanto as well as Kajanus, Sibelius and Gallén at a table full of empty bottles. Somewhere between 1896 and 1900, Gallén cut off the left side of the painting showing a female figure with the skin of her naked body peeled off, sitting on the table in front of the men. One day at the Hotel Kämp in 1903, Sibelius composed the Valse Triste for the play Kuolema (Death), which premiered in December at the Finnish National Theatre in Helsinki. That day, the impulsive artist Sigurd Wettenhovi-Aspan, to whom we owe this anecdote, had run into Sibelius, who was developing a terrible influenza. They decided to get boxes of quinine powder at the main pharmacy in town and ended up in the piano cabinet on the banquet floor of the Kämp. They wanted to get rid of the flu and ordered only soda with some lemon juice and sugar to wash down the medicine, together with some oysters. The five grams of quinine made Sibelius get deep into his thoughts reminiscing on his youth. He starting to tap the table with the tips of his fingers to the rhythm of a death waltz, the famous, Valse Triste.

The journalistic staff of the Päivälehti newspaper had the habit of going out together to Helsinki restaurants once their work finished around 8pm. They regularly ended up at one of the tables at the Lower House of the Kämp, where the ingenious author Eino Leino drank a black mocca on his sobering-up days. The Päivälehti founder Eero Erkko was the organizer of the resistance movement Kagaali, which intended to defend the legal and political status of the Grand Duchy of Finland in the years of “russification”. In 1901, Kaagali was planning a meeting in August at the Kämp. When the police got wind of it, it was moved to a secret hideout outside of Helsinki. The following year however, Erkko reserved the entire banquet floor of the Hotel Kämp for a large assembly meeting of Kagaali. The authorities only heard about the meeting the day after, although the official residence of Governor-General Bobrikov was situated obliquely opposite Hotel Kämp.

In 1910, one of Helsinki’s first motion picture theatres, Helikon, was opened in the Hotel Kämp’s Ballroom with a separate entrance. It went bankrupt in 1925 and was reopened one year later by another company which ran it as the Olympic Cinema for another four years, after which it was closed for good and the space was restored to again serve as the Hotel Kämp Ballroom. In 1914-15, a sixth floor was added to the Kämp and its façade changed by the architect Lars Sonck. In addition, all rooms were renovated, modernized and equipped with water pipes, radiators, cold and hot water. Most rooms were equipped with modern bathrooms, and the popular “American Bar” opened. This was a reaction to the opening of Seurahuone in 1913, a new hotel opposite Helsinki’s railway station.

The Kämp’s kitchen was run in an almost military-like style with an iron discipline, with a strict distribution of tasks between men and women which remained unchanged until after the Second World War. The staff was multi cultural with a Russian baking pies, a German preparing sausages and smoked meat and a Finn taking care of fish. The working language was Swedish with a mix of German, Russian and French words. Meals normally started with a Swedish-style smörgadsbord and schnapps.

After the death of Municipal Councilor Grönquist, the president of the Kansallis-Osake-Pankki, Mr. Paasikivi, bought the Kämp for his Finnish bank in 1917; he remembered that the bank’s founding meetings had taken place in the Mirror Room in 1889. It was a revolutionary time in Finland, whose Parliament approved on December 6, 1917 the Declaration of Independence, making the transition from a Russian province, the Grand Duchy, to an independent nation. It led to a bloody Independence and Civil War which ended only at the end of May 1918. In the autumn of 1917, the Kämp was affected by the great strike. Only guests residing at the hotel were served by the waiters. Two Red Guards controlled the incoming and outgoing customers. After the Red Guards took control of the city, the Kämp – as the meeting place of the bourgeoisie – was frequently inspected by the revolutionaries. One day, Manager Lundblad was ordered to switch on the light in the banquet hall. It took the short and stubby man some time to reach the switch, which the patrol interpreted as being slow on purpose, which resulted in the arrest of the Manager, who was not liberated until a few weeks later, apparently because he was Swedish.

General Count Rüdiger von der Goltz, commander of the Baltic Sea Division of the German Imperial Army which took part in the Finnish Civil War made the Hotel Kämp into his headquarters.

The heavy fighting between the White and the Red Finns took its toll. The Hotel Kämp was turned into a hospital for the wounded victims of the Civil War. The Swedish staff was ordered to leave the country, including the hotel manager and his wife. The Hotel Restaurant changed owners. In April 1918 the Baltic Sea Division of the German Imperial Army marched to Helsinki under the direction of General Count Rüdiger von der Goltz, who turned the Kämp into his headquarters.

By the time the Finnish national hero of the Finnish Freedom and Civil War, Baron Gustaf Mannerheim arrived in Helsinki, the Hotel Kämp had started to be used to host meetings of the country’s unofficial military command, which was about to create a Finnish Army and nominate Mannerheim as its Commander-in-Chief.

The Hotel Kämp has dedicated its most luxurious apartment in the new Hotel Kämp to Marshal Mannerheim, who became the Republic’s sixth President in 1944. He had lived at the hotel for a long period in 1919 before moving to his own residence. In the Mannerheim Museum in Helsinki you can admire the great man’s camp bed, which he took with him on his extensive travels. It is not known however whether he also used it at the Kämp. The “Marshall’s drink” – a completely filled up glass – is known by all Finns. Mannerheim was always quick with a compliment for the hotel staff when an evening was a success, but was known to make nasty comments when someone failed in his duties. Hotel Kämp became the leading hotel in the capital of the newly independent nation. Helsinki now hosted the headquarters of big businesses, banks, insurance companies, trade unions, political parties and, due to its geo-strategic location bordering Russia, an important number of embassies and consulates.

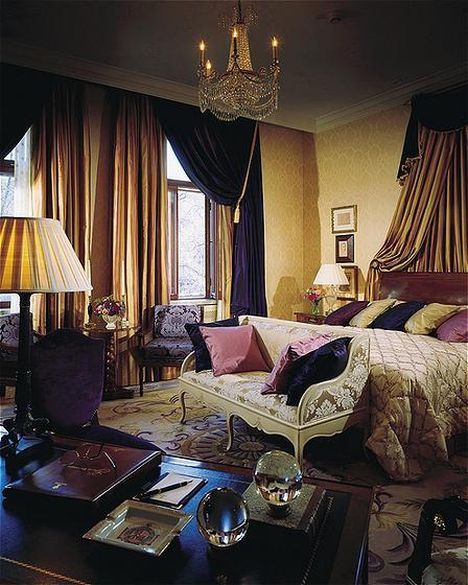

The Mannerheim Suite bedroom

In the years of the Revolution and the Civil War 1917-18, life was not all sweets and candy. Alcohol and food were rationed and in June 1919, a Prohibition Act came into effect, the only country other than the United States where prohibition laws were put in effect, with the result of the creation of a large black market. In 1922, the law became even stricter, being drunk in public was now considered a crime. At Hotel Kämp, as in most restaurants and cafés, drinks were served, although this was denied in public. The “hard-tea”, a mix of half tea, half spirits, with a small amount of sugar added, was one of the hotel’s hot favorites. In addition, cognac, whiskey and wine, brought in by sailors, were all served too. In 1926, the Prohibition inspectors raided the hotel – not for the first time – and discovered in room 34 – officially under renovation – a total of 137 bottles of Estonian liquor. The hotel manager insisted that he had been abroad and, therefore, was not guilty. In the end, the headwaiter and a waiter admitted illegal possession and sale of alcohol. As a consequence, the Governor closed the Kämp restaurant for two months. The Prohibition ended with a referendum in 1932. A photograph captures the moment at the Kämp when hotel manager Ville Weman reopened the door to the hotel’s wine cellar. The American Bar also reopened without delay.

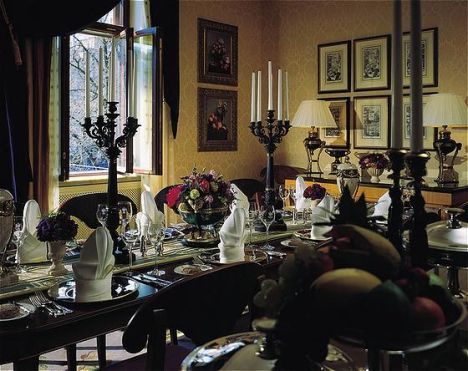

The Mannerheim Suite dining room

The 1940 Summer Olympics had been given to Finland. In early 1939, 47 out of 64 invited countries confirmed their participation. 100,000 guests were expected in Helsinki, where only a handful of excellent hotels such as the Kämp, the Carlton, the Grand, the Helsinki and the Torni existed. The well-organized and prepared for games did not take place because Germany started the Second World War by attacking Poland in September 1939. Finland declared a full mobilization in October 1939. On November 30, 1939 the Soviet Union attacked Finland and soon after started its air raids over the city of Helsinki. The Olympic Games had to be cancelled. On December 6, 1939 the Hotel Kämp was asked to organize Finland’s Independence Day reception. Under the political circumstances and with a war being fought, the President decided not to give a reception. However, the government requested an evening cocktail for the diplomatic corps, foreign correspondents and the political elite. The Minister of Foreign Affairs was asked to mobilize retired waiters and bakers to cater for it. The guests were requested to keep everyday clothes for the reception. The Minister of Education Uuno Hannula attracted all the attention with his grey woolen sweater and red-legged boots. Asked about his unusual outfit, he replied to the amazement of his colleagues that this was indeed his everyday clothing.

The Finnish Winter War with the Soviet Union from November 30, 1930 to March 13, 1940 attracted war correspondents from around the world. Most of them stayed at the Hotel Kämp, where the State Council had opened an information centre for the press on the hotel’s second floor, the Kämp Press Room. Among the famous correspondents were Martha Gellhorn, Indro Mantanelli, Max Mehlem, Morgan Vernon, Barbro Alving and many more. They gave publicity to the small country’s brave fight for independence, in which they finally succeeded. Most correspondents fought Finland’s Winter War at the Hotel Kämp’s bar, which had been reinforced and turned into a bomb shelter. Finnish journalists, employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and politicians and industrialists important to the war effort gathered here too. Max Mehlem, the correspondent of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung and chairman of an international journalists’ association, caught pneumonia after visiting the front in the midst of winter. He was a regular guest at the Hotel Kämp and for his recovery, he had a hotel room transformed into a “hospital room”.

In 1941, hotel manager Ville Weman died. His daughter, Greta Lindblom, took over his position. She had learned the hotel business from scratch and traveled the world to study languages. After returning to Helsinki, she worked at Hotel Kämp for eight years. Strict rationing ended only in 1948, followed by a sharp increase in restaurant prices, which had almost remained unchanged since the 1930s. Coffee prices were not liberated until 1954. With the end of the war and consequent political liberalisation, the communists, previously in the underground, re-emerged in 1945. Waiters went on strike in March 1945. At the Hotel Kämp, the guests had to go themselves into the kitchen to get their meals. During this period at the Kämp, The Soviet representative in Finland, Zdanov, President Mannerheim and Prime Minister Paasikivi, often accompanied by the post-war President of Estonia, Johannes Laidonner on one of his frequent visits to Helsinki, together with the Polish, Latvian, Lithuanian and East Prussian Ambassadors to Finland could all be seen at the hotel. Paasikivi had been a longtime director of Kansallis-Osake-Pankki, the company that owned the hotel. He used to sit downstairs in a quiet annex called “himmeli”, separated by a curtain, from where he could leave unnoticed by a secret door through a stairway from the bank’s headquarters.

During the crucial time before the Finnish participants in the Potsdam Conference of mid-1945 set off, Prime Minister Paasikivi reserved a room for himself and six ministers on the banquet floor, with an empty, insulated room to each side. The headwaiter of the time, Mauri Lindberg, gave his graduation pen to Paasikivi to sign any agreements made, who told him: “This pen will not be used again.” In 1946, the reception for the Finnish Army celebrating its victories through the Winter War and WW2 was held at Hotel Kämp. Marshal Mannerheim, who had been ill that day, was substituted by two generals for the splendid reception at which David Oistrakh played the violin, supported by Einar Englund. Afterwards, the socialist state was handing out princely tips, Lindberg recalled.

Helsinki finally got the chance to host the Olympics in 1952. Two new up-market hotels, the Vaakuna and the Palace, were built for this occasion. The Hotel Kämp, by then the capital’s oldest functioning hotel, modernized its facilities and operations. By June 1952, first-class restaurants were allowed to serve drinks at the counter. The Kämp hired a Dutch and a French bartender and ordered new bar stools. The Olympics were a success for the Kämp, which hosted famous guests including Prince Philip of England, but for many other hotels, the games were financially disappointing. Many celebrities have since stayed at the Hotel Kämp. A memorable occasion was the visit of film star Gregory Peck and his Finnish wife, where they were greeted by a fan crowd of over one thousand people.

Gregory Peck and his Finnish wife, Greta Kukkonen visited Finland.

Greta Peck (January 25, 1911, Helsinki – January 19, 2008, Beverly Hills, California) was a Finnish-American real estate broker and first wife of Gregory Peck. The Kukkonen family immigrated to the United States in 1913 where Greta changed her first name Eine to Greta. She married Peck in 1942 and divorced him in 1955. They had three sons: Jonathan, Stephen and Carey. Greta Peck owned a beauty salon and a real estate agency and was active in charitable causes, raising money for Finnish World War II veterans. Due to those activities, she received the Order of the White Rose from the Finnish Government in 1967. She was also a member of the Finnish-American Chamber of Commerce and received an honorary doctorate from Finlandia University in 1994.

In the autumn of 1962, the Hotel Kämp celebrated its 75th anniversary with another splendid reception. Council of commerce Bertil Tallberg had been a regular guest for 60 years, and building administrator Jussi Lappi-Seppälä stated that he had used hanger number nine in the vestibule’s clothes rack for twenty-five years almost on a daily basis. Among the loyal staff who had served the Kämp for over forty years were employees of ten professions from all hotel departments. They were awarded a badge of honor from the Chamber of Commerce. Over the many years of operation, the wars and natural deterioration had left their mark on the Kämp. The wooden structure of the building revealed cracks in the walls. Water leaks further damaged the hotel’s framework. During a Labor Day dance in the early 1960s, Ms. Lindblom noticed how the Ballroom floor kept bending. She told the orchestra to stop playing, but the people continued dancing until, all of a sudden, everyone noticed the floor giving in portentously. The newspaper headlines: “Kämp is sinking in the mud of Kluuvi.”

After two years of negotiations with the municipal authorities, the owners of the hotel property, Kansallis-Osake-Pankki, decided to preserve the buildings original façade. In 1965, permission was given to demolish the hotel’s façade under the condition to reconstruct it as well as parts of the interior in the image of the original. The hotel and restaurant had already been given notice for the termination of their lease several times, but they continued to operate until March 31, 1965 when Hotel Kämp held its farewell party, with people queuing up out in the street all night. After one last effort to save the original façade, the demolition of the hotel started in autumn 1965. After being rejected, the appeal by the Committee of Archaeological Monuments came too late before the State Council because, by then, the original façade had already been pulled down.

By 1967, Kansallis-Osake-Pankki declared that they had been unable to find anyone to take over the hotel and restaurant business; a hotel with less than forty rooms was considered unprofitable. Public opinion accused the bank of greed and cultural ignorance. By February 1967, the bank’s president Matti Virkkunen was forced to defend the company’s position and stated that everything architecturally valuable had been safeguarded. The façade, the main staircase and the Mirror Room would be rebuilt. However, there was no agreement on the continuation of the hotel and restaurant operations. According to a social-democratic newspaper, the decision had been made by a slight right-wing majority for the benefit of the bank, which erected on the site a business and bank building in the image of the old Hotel Kämp.

The restoration was made in cooperation with the archaeological committee, combining state-of-the-art technology with traditional handicraft. Wherever possible, authentic pieces such as doors, pillars, stairs or iron railings were integrated into the new building. Under the supervision of the sculptor Heikki Häiväoja, the plaster ornaments were remodeled by the interior architect Markku Komonen. Original paintings such as the ones by André and Favén were restored and again set up in their original location. Under the supervision of Professor Antero Pernaja and architect N. H. Sandell, the new building was erected as a copy of Hotel Kämp after the 1914-15 extension, including the colors of the façade Höijer used. Only the Mirror Room was moved to a slightly different location. The new building was inaugurated as the bank’s new headquarter in June 1969, with its banking facilities located in the Lower House and a money exposition in the former newspaper room. When the Kasallis-Osake-Pankki merged with Merita to become part of Nordea, a large banking group, the company refocused and tried to find new uses for its redundant properties. In autumn 1996, the Merita group decided to convert the Kämp building back into being a hotel.

The decision was greeted with joy in Helsinki. The new designs were by architect Petri Blomstedt (1941-1998), after whom suite 612 is named, and included a new, contemporary wing and business facilities. On May 9, 1999 the new hotel Kämp finally opened its doors. Again, people queued up to have a look at “their” hotel. Immediately, the Hotel Kämp’s reputation as Helsinki’s leading hotel was restored. The guestbook contains signatures from the first new prestigious guests the new hotel accommodated, including U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, the singers Whitney Houston, Sting, Bon Jovi, Tina Turner and Shakira, to name just a few. The Japanese Emperor in 2002, Queen Noor of Jordan in 2003, King Harald and Queen Sonja of Norway are some of the notables who have stayed at the Kämp. The Finnish racing driver Mika Häkkinen regularly visits the hotel with his family because he appreciates its privacy.

The Hotel Kämp – all in all, a suitable place to put up one’s feet for a few nights.

A band famous for destroying hotel interior’s was told by their manager that they could “start throwing TV-sets out of the windows straight away. Please feel free to destroy the interior of your rooms. No problem. I have a credit card.” The hotel’s security manager turned pale. But then the band manager reminded the band to bear in mind that they were about to tour Russia and that if the hotels there heard about damage in Helsinki, none of them would take the band and they would have to sleep in bed & breakfasts. “Do you know what that means in Russia?” After this speech, all band members fully qualified for a five-star hotel. The Kämp has a house schnapps (Talonsnapsi), made with an extract of pine, anis and eucalyptus as well as an unknown ingredient, mixed with Koskenkorva Viina (a Vodka). It is an old recipe from Tammisaari, a place 100km west of Helsinki. Only recommended to people used to drinking very strong alcohol.

In today’s hotel, in the reception area, visitors are greeted by two portraits showing the hotel’s founding couple, painted in a later period. In the bar, a painting by Antti Favén from 1915 shows “The Lunch After Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Birthday Party”. In addition to old paintings, the public areas of the Hotel Kämp display contemporary artworks, for instance by Marjatta Tapiola. The 15 suites are located on four floors in the reconstructed old part of the Kämp. The main restaurant, the Grand Café is ‘just’ a popular one with atmosphere; there is no Michelin star gourmet restaurant in any of Helsinki’s hotels. Its new furniture is inspired by photographs of the old one. The breakfast at the Kämp is excellent. An elegantly designed Japanese restaurant, Yume, is located on the ground floor on the left of the hotel entrance. The Kämp Club on the first floor – in Finland called the second floor – is the most stylish part of the hotel. It has a small dance floor and not the old style Grand Hotel feeling. In addition to affordable ones, the bar offers some extremely expensive drinks. The Hennessy Ellipse at 312 Euros per 4cl glass (price as of September 2006) gets regularly ordered. In addition, you can for instance chose from over 40 Champagne brands.

Note: If you’re REALLY interested in this grand old hotel, read “Hotel Kämp Helsinki. The Most Famous Hotels in the World” by Andreas Augustin and Laura Kolbe. (152 p. ISBN: 3-902118113). Andreas Augustin is a journalist and publisher of hotel histories, Laura Kolbe is a Professor of History at the University of Helsinki.

Remembering the Hotel Kämp Press Centre and the Winter War

Australian reporter James Aldridge writing up a story in the Hotel Kämp in December 1939

In early 1940, with around a hundred foreign journalists stationed in Helsinki to cover the Winter War between the Soviet Union and Finland, the Foreign Ministry opened a press centre in the Hotel Kämp. A plaque on the wall marks the days when cigarette smoke and the staccato chatter of Remington typewriters filled the air.

Two of the reporters who had been in Finland for the Winter War, American David Bradley (who had covered the war for the Lee Syndicate and the Wisconsin State Journal) and Swede Carl-Adam Nycop (wrote for the Swedish magazine Se), made the trip back to Finland for the unveiling ceremony of the plaque, and they gave their impressions of what had gone on during and immediately after the intense conflict that had temporarily been the main event in the early “Phoney War” days of World War II. The principal memories were of the profound relief of the Finns when the war ended, and the sense of emptiness that everyone felt when the fighting was all over.

If you’re in Helsinki, go and have a drink at the Hotel Kämp Bar, close your eyes and imagine you’re hanging out there with Virginia Cowles, Martha Gellhorn, George Steer, Geoffrey Cox and the other War Correspondents of the Winter War……

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

4 Responses to Hotel Kämp: a History of one of Helsinki’s most famous Hotels