On the outbreak of WW2 in September 1940, Canada had declared war on Germany together with the other Dominions of the British Commonwealth, although in Canada’s case and as a result of Canadian politics, it was seven days after Britain. Up to the outbreak of war, both the government and the public remained reluctant to participate in a European war, in part because of the memories of the Conscription Crisis of 1917 that had divided French and English Canada. Nonetheless, Canadian Prime Minister MacKenzie King had not changed the view that he had held as early as 1923 that Canada would participate in a war by the Empire whether or not the United States did. By August 1939 his cabinet, including French Canadian members, was united for war in a way that it probably would not have been during the Munich Crisis, although both cabinet members and the country based their support in part on expecting that Canada’s participation would be “limited”.

A Nation Unwilling and Unprepared – Canada on the verge of WW2

Canada in late 1939 was far from prepared for war. Canada had informally continued to follow the British Ten Year Rule that reduced defence spending even after Britain abandoned it in 1932. Having suffered from nearly 20 years of increasing neglect, Canada’s armed forces were small, poorly equipped, and, for the most part, unprepared for war in 1939. King’s government began increasing spending in 1936, but that increased spending was unpopular. The government had to describe it as primarily for defending Canada, with an overseas war “a secondary responsibility of this country, though possibly one requiring much greater ultimate effort.” The Munich Crisis of 1938 caused annual spending to almost double.

Nonetheless, in March 1939 the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force (PF), Canada’s full-time army) had only 4,169 officers and men while the Non-Permanent Active Militia (Canada’s reserve force) numbered 51,418 at the end of 1938, mostly armed with weapons from 1918. In March 1939 the Royal Canadian Navy had 309 officers and 2,967 naval ratings, and the Royal Canadian Air Force had 360 officers and 2,797 airmen. In September 1939 Prime Minister MacKenzie King’s cabinet rejected the proposal by the Canadian Chiefs of Staff to create two army divisions for overseas service, in part due to the cost.

At the outbreak of war, Canada’s commitment to the war in Europe was limited by the Canadian government to one division, with a further one division in reserve for home defence. King’s “moderate” war strategy won his Liberal Party the largest majority in Canadian history in the elections of March 1940. Despite this, by the end of the war, Canada would possess the fourth largest air force and the third-largest naval surface fleet in the world, as well as a not-inconsiderable Army through which some 730,000 men passed through over the course of the war. Approximately half of Canada’s army and three-quarters of its air-force personnel never left the country, compared to the overseas deployment of approximately three-quarters of the forces of Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. In part, this reflected Mackenzie King’s policy of “limited liability” and the labour requirements of Canada’s industrial war effort. But it also reflected the objective circumstances of the war and the internal political situation with Quebec, where opposition to conscription and involvement in the War was greatest. With France defeated and occupied, there was no Second World War equivalent of the Great War’s Western Front until the invasion of Normandy in June 1944.

When we come to look at the Canadian Volunteers, we will examine Canada’s military preparedness and the internal political situation in greater detail but for now, as a general introduction, this should suffice.

The Canadian Automobile Industry and pre-War and War-time Finnish Military Orders

Leaving aside military unpreparedness for war, in terms of industrial capacity, Canada had become one of the world’s leading automobile manufacturers in the 1920s, owing to the presence of branch-plants of American automakers in Ontario. In 1938, Canada’s automotive industry ranked fourth in the world in the output of passenger cars and trucks, even though a large part of its productive capacity remained idle because of the Depression. During WW2 this industry was put to good use, building all manner of war material, and most particularly wheeled vehicles, of which Canada became the second largest (next to the United States) producer during the war. Canada’s output of nearly 800,000 trucks, for instance, exceeded the combined total truck production of Germany, Italy, and Japan throughout WW2. Approximately half of the British Army’s transport requirements were supplied from Canadian manufacturers. The British Official History argues that the production of soft-skinned trucks was Canada’s most important contribution to Allied victory and in this the Canadian Military Pattern (CMP) truck played a crucial part.

What is now little known is that a major part of the design for what was to become the ubiquitous Canadian Military Pattern (CMP) truck originated in Finland at the Ford Manufacturing Plant outside Helsinki. Early in 1937, Ford Suomi Oy and Sisu Oy (the Finnish state-owned heavy vehicle manufacturer) were each invited by the Finnish Ministry of Defence to produce a design for a new and robust 4×4 truck for military use. It was specified that in addition to military use, the trucks should be suitable for a variety of civilian roles including work in the forestry industry, as agricultural/farm transport, as forest fire-fighting trucks and as snow ploughs (the Government’s stated intention was to partially subsidize manufacturing of these trucks and make them available at low cost for Finnish civilian purchase and use, contingent on being listed and available for use by the military in the event of a war). In the end, Ford Suomi and Sisu pressured the Ministry of Defence and the Minister of Finance to allow them to pool their design expertise and submitted a joint design. Manufacturing was to be split between the two companies based on available capacity.

The prototype design of a 15-hundredweight light military truck that had at this time been recently adopted by the British War Office had formed a starting point for the Finnish design. The design that re-emerged in heavily modified form from the joint Ford Suomi / Sisu design team was a standardized vehicle particularly amenable to mass production, with a 239 cu in (3.9L) V8 engine, 4WD, a short, “cab forward” configuration that gave the trucks a distinctive pug-nosed profile and a 3 ton load capacity. The design was accepted as the MSK Truck (Maavoimat Sotilaallinen Kuvio – “Maavoimat Military Pattern”) and in mid-1938, the first production model rolled out of the Ford Helsinki plant (none of the trucks were produced at the Sisu factory, which was then concentrating on other orders).

Ford Helsinki’s capacity was limited and with the Munich Crisis the Emergency Defence Expenditure program that was the immediate Finnish reaction to the increasing gravity of the situation in Europe, the Finnish Ministry of Defence gave the acquisition of additional trucks from overseas a high priority. In looking for manufacturers, Finland was also cognizant of the situation that Britain and France might find themselves in if war with Germany broke out (especially given the problems that had already been encountered with orders for military equipment from these countries) and it was decided that as much of the equipment to be purchased as possible should come from North America.

With regard to the trucks, negotiations were entered into with Ford Canada (by Ford Suomi) and in early 1939 a contract was signed for the delivery of 1,000 of the Finnish-designed trucks. Given the involvement of Ford Suomi in the design, the initial order for 1,000 trucks went to Ford Canada and by May 1939, the first MSK 4WD 3 Ton Trucks (MSK=Maavoimat Sotilaallinen Kuvio – “Maavoimat Military Pattern”) were rolling of the Ford production line in Ontario. Under threat from the Soviet Union, Finland increased the overall size of the order to 2,500 trucks in August 1939, and then to 5,000 in December 1939, only days after being attacked.

With the increase in the size of the order in August, and taking into consideration the emphasis the Finnish Government was placing on speed of delivery, Ford Canada made the decision to bring in their rival, General Motors of Canada. In August 1939 the two companies pooled their manufacturing teams and at the same time, the Finns licensed manufacturing rights to the trucks to both Ford and General Motors, who threw their engineering design teams into further improving the design – the result of which would go on to become the Canadian Military Pattern (CMP) truck, which served throughout the British Commonwealth for the duration of WW2 – and the improvements were progressively included in the vehicles being manufactured for Finland.

MSK (Maavoimat Sotilaallinen Kuvio – “Maavoimat Military Pattern”) Truck, 4WD, 3 Ton – this is a long-wheelbase version

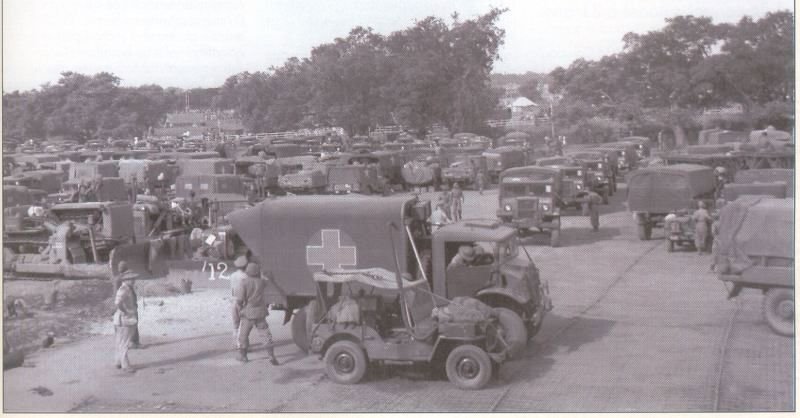

MSK (Maavoimat Sotilaallinen Kuvio – “Maavoimat Military Pattern”) Trucks at a rear area depot, Eastern Karelia, Summer 1940

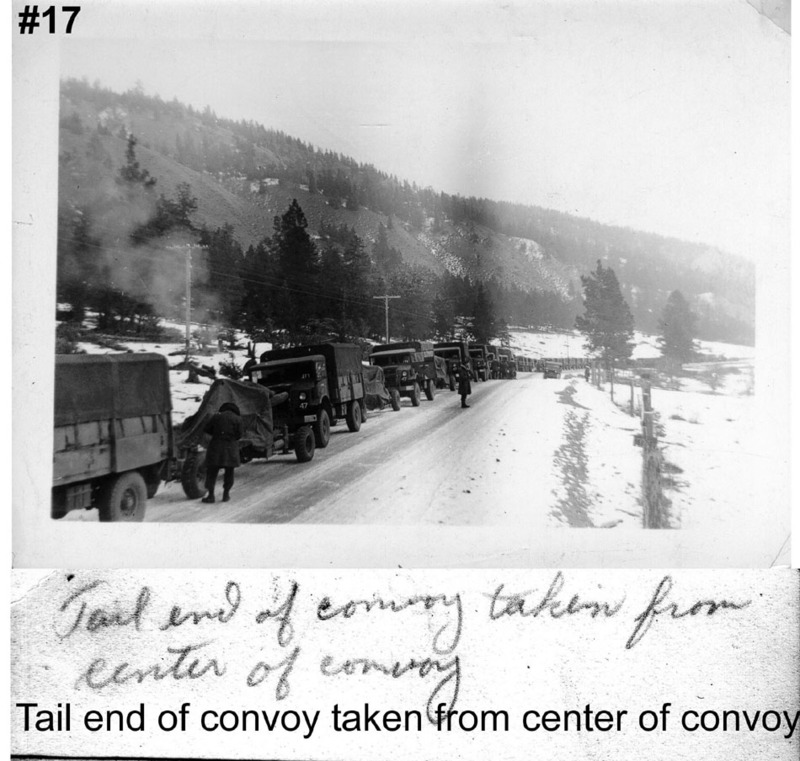

The Ford Suomi / Sisu designed Maavoimat Military Trucks (4WD, 3 Ton) would come to form the backbone of the Maavoimat’s logistical transportation by the end of the Winter War. Here, the trucks have been offloaded and assembled at Lyngenfjiord and are en-route to Tornio.

The first shipment of some 500 Trucks had arrived by freighter in Turku in November 1939, shortly before the commencement of the Winter War. They were rapidly uncrated and assembled and issued to military units, initially to Field Artillery Regiments to improve mobility and logistical resupply, later on to Divisions on the Karelian Isthmus and then, as more arrived, to Divisions on other fronts.

Ford Suomi / Sisu designed Maavoimat Military Trucks (4WD, 3 Ton) lined up outside a storage facility in Tampere shortly before the outbreak of the Winter War as the Maavoimat mobilised

After the outbreak of WW2 and the Canadian declaration of war in September 1939, the Canadian Government had debated whether to cancel deliveries to Finland and take over the orders for the Canadian military. The debate was still underway when the USSR attacked Finland on the 30th of November 1939. In Canada, as elsewhere, public support for Finland was, as we will see, both widespread and deeply felt and there was public demand to support Finland. The end result was that while Canada did not have any immediate “military” manufacturing capability with which to assist Finland (and in any case weapons were in such short supply that anything that could be produced immediately went to the Canadian military) trucks were another matter. The Finnish truck order was confirmed and at the same time, as has been mentioned, the Finns licensed manufacturing rights to the trucks to both Ford and General Motors for construction for the Canadian, Commonwealth and US militaries.

The trucks for Finland were manufactured by the Chevrolet division of General Motors of Canada Ltd and by the Ford Motor Company of Canada. The Canadian subsidiaries of the two largest American vehicle manufacture

MKS Artillery Tractor with Howitzer – Commonwealth Division artillery unit at the Syvari Front, August 1940….

rs were able to rapidly ramp up their production because of an unusual degree of inter-company collaboration, the use of interchangeable parts, and because of the large amount of idle production capacity that was a lingering result of the Great Depression. Skilled labour was easy to rehire and Canada’s limited mobilization had not impacted the manpower available for industrial expansion in any way.

As a result, ramping up was not hindered by personnel bottlenecks as it was in countries where there was a heavy industrial base. Various models were built – Heavy Utility Trucks, Artillery Tractors, Fuel Tankers, Armoured Trucks, Command Trucks, Radio Trucks, Ambulances and an innovative Finnish-designed Armoured Personnel Carrier version, of which some 400 were specially ordered, constructed and which arrived in Finland in June 1940 together with a further 200 Armoured Cars, also based on the same chassis.

By the end of the Winter War, thousands of Maavoimat Military Pattern Trucks would be in service with the Finnish military – here, a large logistics Convoy heading for the front takes a break. The close-up column of trucks indicates the level of confidence the Maavoimat soldiers had in the ability of the Ilmavoimat to dominate the air war – in the early weeks of the war, this type of bunching up would not have been in evidence…

In keeping with the rapidly evolving Maavoimat doctrine for front line vehicles, the gasoline engine was replaced in the production model with the proven and easy to procure Cummins I6-170hp diesel engine – and thanks to Neste’s completion of a new and rather innovative diesel fuel plant (essentially a Fischer-Tropsch process) that produced good quality diesel from biomass, diesel fuel for the trucks would not be an issue by the end of the Winter War. The Ford-Sisu Truck and the Sika AFV derivative would be used as gun carriers, mortar carriers, artillery tractors, fuel tankers, command trucks, signals trucks, armoured personnel carriers and ambulances to the end of the war. Sisu and Ford Helsinki would go on to manufacture this vehicle and derivatives of it, including a half-track version, well into the post-WW2 years.

Prototype Finnish-designed “Armoured Truck” version of the Ford/Sisu 4WD/3 ton truck – 400 were ordered from GM Canada, constructed and arrived in Finland in June 1940 where various modifications were made. Almost all of these armoured trucks were allocated to the Maavoimat Pansaaridivisoona’s, of which by June 1940 there were 4 in existence (1 from before the war, 1 formed up with purchased and delivered tanks and 2 formed up using Red Army equipment captured intact in the first two to three months of the war.

The “Sika” AFV

The “Sika” AFV was a locally-designed modification of the original truck design – the same chassis and engine were used but with a one-piece armoured shell (the armour was standard Tornio Steel Works-made armour plate and the glass was also strengthened bullet-proof glass). The vehicle itself was rather top-heavy and the additional weight did not make for good cross-country performance in rugged conditions – but it could cope with moderate terrain. There was a driver and a passenger seat in the front, separated by the gear box cover, while the rear compartment had two bench seats placed back to back in the center which could seat four (or six if squeezed). There was a mounting for a 12.7mm machinegun front-center, and two machinegun mounts on either side of the vehicle to the rear although armament tended to be non-standard, with crews adapting whatever they could lay their hands on as they saw fit.

Photo, Left: A further version, radically innovative for its time, was the Sisu Infantry Carrier. In Maavoimat use, this Carrier would be commonly referred to as the “Sika”, largely due to its ungainly looks and its handling. The armour was effective against small arms fire, light machineguns and shrapnel but not against 20mm cannon at close range or against anti-tank guns. In this photo, the armour “shell” has been jacked up off the chassis for routine maintenance. Entry to the “Sika” was through doors at the rear, the armour was standard Tornio Steel Works-made armour plate and the glass was armoured. The vehicle had a tendancy to roll about, caused by the armour making it top-heavy. Visibility for the driver was limited and it took a while to stop as the brakes had not been upgraded. There was a driver and a passenger seat in the front, separated by a gear box cover, while the rear compartment had two bench seats placed back to back in the center which could seat four (or six if squeezed). There was a mounting for a 12.7mm machinegun front-center, and two machinegun mounts on either side of the vehicle to the rear.

Photo, Left: his version of the “Sika” was equipped with a Finnish-manufactured twin-20mm Lahti cannon and seems to be carrying five soldiers in the rear compartment in addition to the two crew in the front. The armour mods (6-14mm of armour) meant that the chassis was overloaded and this was the cause of structural problems – according to those who drove them “they were a real bitch”. Many a driver also got smashed fingers when, without first shouting a warning, the front passenger crewman dropped the visors (the ten to two steering position was not a good move in a Sika). It had plenty of faults but it also provided good mobility (in summer at least), firepower and protection. Armed with Lahti twin 20mm Cannon on the front mounting and two machineguns mounted on the side mountings, the firepower of the “Sika” could be devastating against enemy infantry and light vehicles caught in the open.

Photo, Left: A “Sika” from the 21st Pansaaridivisoona on the move in Eastern Karelia, late summer 1940 as the Division moved to encircle an attacking Red Army Group. The mobility and firepower offered to the Jaeger’s of the 21st Pansaaridivisoona by the “Sika” Armoured Carriers contributed significantly to the decisive outcome of the summer battles. The fast-moving and highly aggressive Maavoimat units, provided with massive artillery support, air superiority and on-call close air support, tied together by a tactical radio net that far surpassed that in service with any other military in the world, completely outclassed a Red Army that was left headless as a result of Maavoimat Special Forces units and Ilmavoimat ground-attack aircraft eliminating many Army Group, Divisional and Regimental Headquarters and interfering significantly with Soviet logistics. Note the three machinegun mounts visible.

Production of the “Kettu” Armoured Car in Canada

As we will see in a subsequent Post in rather more detail, Sisu had in 1938 begun producing what was known as the “Kettu” (Red Fox) Armoured Car in small numbers. The Kettu was intended for use by armoured reconnaissance companies and was light, fast and well armoured for this task – and fitted with the Bofors 37mm, which at this time was the standard Maavoimat anti-tank gun, with secondary armament consisting of a single machinegun. An additional machinegun mount was fitted on the outside of the turret for an external belt-fed Lahti 20mm cannon which could be used by the vehicle commander, albeit from a partially exposed position. The Kettu had a three man crew – the commander, the driver and a gunner. Speed was 50mph and operational range was initially 200 miles, although later versions were fitted with larger fuel tanks to extend the range.

Maavoimat “Kettu” Armoured Car: June 1940. Brand new and just delivered, a Kettu Armoured Car being tested prior to handing over to the Reconnaissance Company to which it was being assigned.

Production of the Kettu by Sisu was not the highest priority and from the start of production in mid-1938, only one a week rolled off the line. By mid-1939, with the sense of heightened urgency, the introduction of two shifts saw production climb to three per week. Even with this, by the outbreak of the Winter War, a mere 130 “Kettu” Armoured Cars were in service, equipping 5 Reconnaissance Companies (each of the 3 Regimental Battle Groups of the 21st Pansaaridivisoona included 1 Reconnaissance Company, with 4 Platoons of 6 Armoured Cars each), while the remaining 2 Company’s were assigned to the Corps on the Karelian Isthmus. (Note: some French Armoured Cars equipped a number of Reconnaisance Companies, these will be covered elsewhere). This was far below the intended Table of Organisation, which was for each Division to have an Armoured Car Reconnaissance Company assigned. With a small training establishment, this would have required a further 4-500 Armoured Cars – very much a “nice to have” and not something that was ever envisaged as being achievable.

In designing the “Kettu”, Sisu once again had not tried for an original design. Rather, they had adopted a design which was based very closely on the British Guy Armoured Car that the British Company, Guy Motors, had underway. The Maavoimat had been in discussions with Guy well before the Munich Crisis and had purchased a license for the design together with expert engineering advice from Guy – who had also helped Sisu with improved construction techniques. The “Kettu” superimposed the Guy-designed armoured car hull on an MKS Truck chassis. These were constructed used welding rather than riveting (something Guy Motors had suggested, recommending welding as being more suitable and effective). To that end Guy assisted Sisu in developing the necessary techniques including rotating jigs which meant the bodies and turrets could be produced quicker and cheaper. However, even with the actual outbreak of the Winter War, the Sisu production line was running at full capacity and production could not be scaled up beyond 3 per week – which in the event proved insufficient to replace combat losses.

In August 1939, with the threat of war with the USSR looming, Finland placed an order for 200 “Kettu” Armoured Cars with General Motors Canada. The Maavoimat specified a welded hull based on the Guy Motors design (but with what the Maavoimat considered to be some design flaws rectified). The hull was designed with a sloped glacis plate and a rear mounted engine, with mounts for a Nokia radio set (to be installed following delivery in Finland). The Maavoimat specified a turret mounted Bofors 37mm gun (the gun to be installed in Finland as US/Canadian manufacturing capacity in mid-1939 was not available to meet the demand for manufacturing suitable guns) with secondary armament consisting of a single machinegun. An additional machinegun mount was fitted on the outside of the turret (and more often than not, a Lahti 20mm belt-fed Cannon would be mounted, giving the “Kettu” quite awesome firepower). The armoured car had a three man crew – the commander, the driver and a gunner.

Maavoimat Armoured Car: Late 1940, during the withdrawal from Soviet Karelia after the signing of the Peace Agreement

As mentioned, the first order for 200 Armoured Cars was placed in August 1939 and these were received in Finland as a single shipment in June 1940. In November 1939 a further 200 were ordered, but these were taken over by the Canadian Government in June 1940 and shipped to the UK to help re-equip the British Army after the disastrous losses experienced in France. In service with the Maavoimat in time for the heavy fighting over the summer and autumn of 1940, the Canadian-built “Kettu” Armoured Cars were allocated to the 4 Pansaaridivisoona and were used for short and long distance reconnaissance, forward artillery control vehicles and for rapid securing of tactical features. While also intended for protective duties with logistical column movements, there were never enough of them to carry out this function. With the Bofors 37mm gun, they also had a main armament that was effective against most Soviet tanks – and the belt-fed Lahti 20mm gave them additional protective and offensive firepower if needed. As a consequence and given their ability to move rapidly, they were often used defensively to blunt Soviet tank attacks. Firing from prepared positions or from cover, they often provided significant and effective support in delaying actions although in doing so they did suffer losses – the battles were certainly not one-sided and by the end of the Winter War, some 50% of the armoured car force had been lost in combat.

The MKS Trucks and the Kettu Armoured Cars were the only significant assistance (other than the Brigade of Volunteers and non-combat related supplies such as wheat and winter clothing) that Canada would provide, but even this was of substantial assistance. The large numbers of MKS Trucks would significantly enhance Maavoimat logistical capacity, while the “Kettu” Armoured Cars would enable the Maavoimat to keep strong armoured reconnaissance units in being throughout the duration of the war.

Aid from Canada

As can be seen, Military Aid from Canada to Finland was limited by the extent of what was available in Canada. The one facet of Canada’s economy that enable a significant military contribution to be made was the Canadian automobile industry and it’s ability to quickly manufacture trucks and armoured cars in quantity. Weapons and munitions however, were not available for the Canadian armed forces, let alone for Finland’s and while armoured cars were manufactured, they were shipped out with no weapons. Nevertheless, Finland was grateful, just as she would be grateful for the civilian-led fundraising campaign run in Canada, and just as she would be grateful for the Brigade of Canadian volunteers, un or semi-trained as they were. These aspects of Aid from Canada for Finland will be covered in a subsequent Chapter.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

5 Responses to Aid from Canada