An interesting cultural theme of Finnish Film in the 1920’s and 1930’s

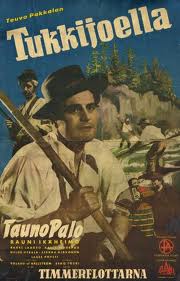

Tukkijoella

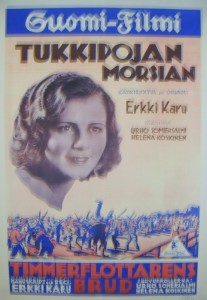

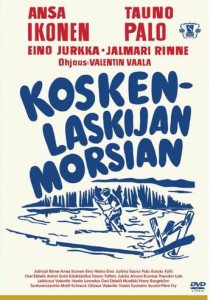

The golden age of Finnish Film began in the 1930’s, when going to the cinema became a wildly popular pastime. Within this rapid popularity of a new media, an interesting cultural theme of the 1920’s and 1930’s was the popularity of books and films about logging – an early example being Erkki Karu’s 1923 film, “The Logroller’s Bride” with superb cinematography by Jäger and Oscar Lindelöf. A later movie was “Tukkijoella” (Log River – 1928). Films of this genre gave the Finnish cinema and the viewing public one of its most popular characters – the lumberjack (tukkijatka, tukkipoika, tukkilainen) who at his most heroic hour becomes the log-roller or the shooter of rapids (koskenlaskija). The significance of this character in Finnish film is comparable to that of the Cowboy on American cinema. He is the pioneer, the wanderer, the adventurer. He negotiates the frontier, he is an embodiment of the conflict between wilderness and civilization. We meet this figure in “Koskenlaskijan Morsian” (The Logroller’s Bride), 1922, remade 1937), “Tukkijoella” (Log River, 1928 – remade 1937 and 1951) and in “Tukkipojan Morsian” (The Lumberjack’s Bride, 1931) as well as in others.

These “logger films” depict log driving as a traditional Finnish livelihood, as well as showing the relationship between nature and civilization. In Koskenlaskijan Morsian (The Logroller’s Bride) by Suomi-Filmi from 1937, the film’s highlights are usually visually spectacular scenes where the log drivers ride down the rapids on rafts. The struggle against nature’s powers is visible throughout the film, and the contrast between the harsh winter and bountiful summer is clear. These kinds of films have their origins in Finnish literature and theater and were very popular.

Tukkipojan Morsian

Even though religion was in a strong position in Finland, openly religious statements were avoided in Finnish film. The companies feared the audience might shun such films. Koskenlaskijan Morsian was an exception to this trend: The fear of God and the concept of accepting one’s destiny were dominant in the Laestadian community of northern Ostrobothnia depicted in the film. Overall, the film received positive reviews, and director Valentin Vaala’s style of portraying nature was praised. On the other hand, the reviews also thought that the plot was somewhat confusing and boring at times (Uusitalo et al. 130-133).

Erkki Karu, founder of Suomen Filmikuvaamo (later to become Suomi-Filmi) and then Suomen Filmiteollosuus directed the most important films of the era and was the prime figure of Finnish cinema before his early death in 1935. His “The Village Shoemakers” (1923) is the essential silent masterpiece, a freshly told folk comedy after Aleksis Kivi’s play with mildly experimental camerawork by German Kurt Jäger. Other notable films by Karu include: Koskenlaskijan Morsian (The Logroller’s Bride) (1923), with superb cinematography by Jäger and Oscar Lindelöf, and also the first Finnish film distributed widely abroad. When Father Has Toothache (1923), a short and surrealistic farce; and Our Boys (1929), a patriotisic forerunner of many military farces.

Audiences of the agricultural country were affected by Suomi-Filmi’s rural subjects. Dealing with deeply national countryside stories remained as company’s policy through the silent era. Occasionally there were some attempts to make more urban, or more “European” films like Karu’s Summery Fairytale (1925), but the public stayed away. Another important director at Suomi-Filmi was Puro, who made the company’s first feature “Olli’s Years of Apprenticeship” (1920) and one of the few Finnish horror films, “Evil Spells” (1927). An interesting oddity of the last two silent years was Carl von Haartman, a soldier and an adventurer, who had worked as a military advisor in Hollywood. Because of this he was considered capable of directing films. His two upper-class spy dramas, The Supreme Victory (1929) and Mirage (1930), were quite passable, but didn’t attract the public.

Koskenlaskijani Morsian

The significance of Finnish film in ordinary people’s lives in the 1930’s is indisputable. Miraculously, almost every film produced in the 1930’s was seen by more than 400,000 people (out of a total population of around 3,500,000), despite the poor economic situation. However, the cost of admission was still so low that almost everyone could afford to go see a film, because they were usually screened at community halls or youth clubs, particularly in rural areas where the bulk of the population still lived. Despite opposition from many older people, in the 1930’s the young often went to great lengths to see a new Finnish film: they would hitch-hike a hundred kilometers to the nearest theater or save every penny for months to afford to buy tickets. The movies of the time had a tremendous cultural influence, and “logger” movies were a well-defined and popular genre.

The main genres of Finnish film

The main genres of Finnish film can be roughly divided into two categories. One genre consists of major and “prestigious” films, which were carefully produced and had grand themes, objectives and budgets. These films were most often depictions of wars or other historical dramas shot at impressive and authentic locations. Examples of such films are Jääkärin morsian (1938) and Pohjalaisia (1936). The other genre consists of serial productions with lower budgets and lighter themes, such as comedies and farces (and logger movies). Although the first category consists of films that were generally regarded as more prestigious, it does not mean that lower-budget films were not ever equally successful. In fact, a series of good comedies helped lift Finnish film companies back on their feet after the recession in the early 1930’s because they were quick to produce and popular with the audience.

Jääkärin Morsian

Most historical films were made from the predominant political point of view, and the companies preferred filming historical events upon which Finns agreed. Thus very few films of the controversial Finnish Civil War were made because the producers wanted to avoid topics that were considered as being too sensitive . An interesting aspect of historical films is that even though in the 1930s they particularly aimed to unite Finns and lift the national spirit, the films themselves were not built around the importance of the unity of people as the decisive force in winning battles against the enemy. Most of the films focused on individual heroes, great leaders, or self-sacrificing martyrs such as Eugen Schauman in Helmikuun manifesti (The February Manifesto) or Sven Tuuva in Vänrikki Stoolin tarinat (Tales of Ensign Stål), both from 1939.

A large part of the major films’ scripts were based on either Finnish or foreign novels and plays. Additionally, many of the films based on novels or plays made in the 1930’s were remakes of older silent films – the justification for these remakes was in the coming of sound, which added a new dimension to the story as different speech dialects were able to be captured on film.

Erkki Karu

Through the 1920’s and until his death in 1935, Erkki Karu was the leading light of Finnish film-making. Karu had started his career in a theater troupe in 1907 but became interested in cinema during the 1910’s. He was reportedly working to start up his own film company as early as 1915. He would direct, write, edit and produce the comedy short films Ylioppilas Pöllövaaran kihlaus and Sotagulashi Kaiun häiritty kesäloma for Suomen Biografi Oy, both of which were released in 1920.

Karu founded the film production company Suomi-Filmi in 1919, which by the end of the 1920s had grown into the largest company in its field in Finland. Karu not only worked as the CEO, but was also the head director for most of his stay in the company. Working to secure the finances of his company, Karu had to wait until 1922 before starting work on his feature-length debut, an adaptation of the Väinö Kataja novel Koskenlaskijan morsian, which saw its release on New Year’s Day 1923. The film was a success, as was Karu’s next work, the Aleksis Kivi adaptation Nummisuutarit, released in the same year. Because of both the popularity and artistic merit of these works, the year 1923 has been called the pinnacle of Karu’s directing career.

Throughout the rest of the decade and the early 1930’s, Karu continued to direct popular films, such as Myrskyluodon kalastaja (1924), Suvinen satu (1925), Muurmanin pakolaiset (1927) and Nuori luotsi (1928). Suomi-Filmi ran into financial difficulties after the global depression stemming from the Wall Street Crash of 1929 caused the attendance figures of cinemas to drop. Karu was accused of financial irresponsibility by the rest of the company’s shareholders and in 1933 had to resign from the company he had started. After leaving Suomi-Filmi, Karu almost immediately founded what would become his old company’s main rival, Suomen Filmiteollisuus. Karu had originally intended to start the company together with an assistant director from Suomi-Filmi, Risto Orko, but Orko chose to remain with Suomi-Filmi when he was offered the spot of head director. Instead, Karu found another partner, Toivo Särkkä, who would go on to become the most prolific director in not only Suomen Filmiteollisuus but the whole of Finland. Karu held the title of head director in his new company, but during his short stay there could only direct two films, Syntipukki and Roinilan talossa, both in 1935, neither of which was very successful. He died unexpectedly on December 8, 1935

Erkki Karu, founder of Suomen Filmikuvaamo (later to become Suomi-Filmi) and then Suomen Filmiteollosuus directed the most important movies in Finnish film of the era.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland