And now – some of the Officers, NCO’s and men of the Atholl Highlanders

The next Post or two will provide bio’s of a cross-section of the Officers, NCO’s and men of the Atholl Highlanders. It’s not all-inclusive, but it aims to give some idea of the calibre of the men who served under Wingate in the Battalion. They were a real mixture – as will be seen.

Captain Hugo Chandor – Admin Platoon CO

Captain Hugo Henry Chandor, Atholl Highlanders. Wingate appointed him to command of the Battalion Administration Platoon, which would remain at the Battalion’s Base Depot for the duration of the units time in Finland. It was a role he filled capably, although Wingate would at times abuse him mercilessly for perceived failures or slowness in carrying out instructions.

The Volunteers themselves were a mixed bunch. The most senior Officer of the Volunteers when Wingate stepped in was a Captain Hugo Henry Chandor, the intended supply and transport officer. Though he had fought in World War One, reaching the rank of Colonel and commanded a bombing school, as a leader Chandor appears to have been out of his depth – a “nice but very weak character”, as one early volunteer described him, and with “quite insufficient military experience or personality to train and organise volunteers”, in the estimation of another.

Wingate was not particularly impressed by Chandor, but he was also loathe to sack an experienced officer, and so appointed him to command of the Battalion Administration Platoon, which would remain at the Battalion’s Base Depot for the duration of the units time in Finland. It was a role he filled capably, although Wingate, who was certainly no respecter of rank or seniority, would at times abuse him mercilessly for perceived failures or slowness in carrying out instructions.

Chandor was an old Etonian who had been a Cadet in the Eton College Cadet Contingent. At some stage prior to 1921, he had been a sheep farmer in Argentina but had returned to the UK where he married Daphne Rachel Mulholland in 1921 (Daphne had divorced Esme Ivo Bligh, 9th Earl of Darnley in 1920). After Chandor married Daphne, he whisked her and her children from her first marriage away to live in a wooden house with an earth floor at Tres Barras, 600 miles into the interior of Brazil, where he built a sawmill.

After five years they returned to England, Daphne having been poisoned by drinking water from the well, which had dead toads in it. They went back to Chandor’s ancestral home at Worlingham Hall, Worlingham, Beccles, Suffolk. After serving with the Atholl Highlanders in the Winter War, Chandor would return to the UK and farm, also serving as an Officer in the Suffolk Home Guard, for which he received the OBE in 1944 when the Home Guard was finally stood down.

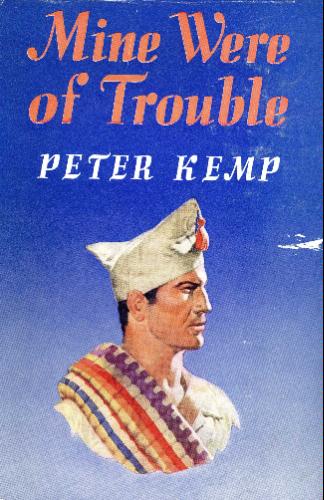

Major Peter Kemp – Rifle Company CO

Peter Mant MacIntyre Kemp (born Bombay 19 August 1913 – died London 30 October 1993), known as Peter Kemp, was an English soldier and writer. The son of a judge in British India, Kemp was educated at Wellington School and proceeded to Trinity College, Cambridge where he studied classics and law. He became notable for his participation in the Spanish Civil War and during World War II as a member of the Special Operations Executive.

As a staunch Conservative and Monarchist, Kemp was alarmed by the rise of Communism and in November 1936, shortly after the end of the Siege of Alcazar, broke off from reading for the bar and travelled to Spain where he joined a Carlist unit under the Nationalists. He was given journalistic cover for entry into Spain by Collin Brooks, then editor of the Sunday Dispatch, “to collect news and transmit articles for the Sunday Dispatch from the Spanish Fronts of War.” He later transferred to the Spanish Legion where, in a rare distinction for a non-Spaniard, he commanded a platoon. Kemp was often badgered by his Spanish comrades about whether he was a freemason due to his protestant background. Wounded several times, he continued fighting until he suffered a shattered jaw and badly damaged hands in the summer of 1938 – the result of a mortar bomb, and was repatriated to England. He wrote about his time in Spain in his book, “Mine were of Trouble” (1957). His later book, “The Thorns of Memory,” also has several chapters on his experiences in Spain, although they read as if they were largely taken from the earlier book with a few revisions.

Seeking adventure but also as a result of his political convictions, Peter Kemp left the UK at the age of 20 to join Franco’s forces in November 1936. Compared to many international volunteers who met with some mistrust, Kemp was generally received with open arms. First, a member of the Carlist Requetes where, assisted by a few OTC certificates, he swiftly became a lieutenant; he then decided to switch to the tougher but rather more elite Spanish Foreign Legion as one of about three or four British officers. Thereon, he recounts a vivid tale of life in Franco’s forces, culminating in several battles and engagements, ultimately being wounded. The value of the book is in its non-leftist perspective.

“Mine Were of Trouble” by Peter Kemp: A well-written account of an Englishman who decided to fight against the left in Spain’s civil war.

Kemp has many interesting things to say, particularly about the bombing of Guernica, which claims Kemp, since the Republicans had bombed Toledo in July 1936, was not the first large-scale bombing of a town, as well as the fact that the Republicans set fire to Guernica, as they had in Irun. He freely admits that the Nationalists were ridiculously naive in their propaganda compared to the more sophisticated and well-supported Republicans. Also an interesting point of view: the involvement of the International Brigades only prolonged a war that the Spaniards could have settled much more quickly and with much less bloodshed if left alone. Food for thought and a bit of a tonic to the usual fairy tale of how “the left were splendid fellows and everyone else was the devil incarnate”. At least we can salvage a bit of historical objectivity instead of being spoon-fed Hemingway, Orwell, Lee, Spender, Koestler, Malraux, Saint-Exupery, et al.

Having barely recovered from his jaw injury, Kemp volunteered for service with the Atholl Highlanders in Finland and was immediately accepted. Wingate spent two hours with him discussing his experiences fighting with the Spanish Foreign Legion in Spain and on the basis of their talk, accepted him and appointed him commander of a Rifle Company with the rank of Major. Kemp would lead his company well over the course of the Winter War, gaining a great deal more experience from working under Wingate and from Maavoimat training.

Peter Kemp with the Atholl Highlanders in Finland – late summer 1940. As part of the “image”, Wingate adopted the Australian bush hats his men wore from the men of the ANZAC and Australian Volunteer Battalions who fought with the Finns – Wingate was a master of publicity and he certainly knew how to create an “image” for his unit.

On his return from Finland after the end of the Winter War, Kemp had a chance meeting with Sir Douglas Dodds-Parker, the former head of MIR – which had been a small department of the War Office and a precursor to the Special Operations Executive (SOE). He was assigned as a pupil at the Combined Operations Training School and joined SOE. After further parachute and commando training he went on several cross-channel raids into Occupied France and was then posted to Albania, where he spent 10 months in clandestine operations in too close proximity to Enver Hoxha.

A mission in Poland resulted in capture by the Red Army and imprisonment by the NKVD. After three weeks in prison, he and Polish Home Army prisoners in the same jail were released by Maavoimat special forces as they and the resurgent Polish Army moved to recover control of Polish territory in the rear of the Red Army from the Soviets. Kemp relates in tones of distinct approval an account of how the Finns dealt rather summarily with the NKVD unit that had imprisoned him and had been interrogating and executing Polish Home Army prisoners. After a further two months in Poland working with the Poles and Finns, he was posted to Siam in the summer of 1945, where he ran guns to the French across the border in Laos. Tuberculosis forced his retirement from the Army once the war had ended.

Post-war Kemp sold insurance policies and turned to writing. As a correspondent for the Tablet he traveled to Hungary to report on the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and helped some students escape to Austria. He was present in the Belgian Congo during the troubles that led to independence as Zaire, and also covered revolutions in Central and South America as the foreign correspondent for The Spectator. His first book ‘Mine Were of Trouble’ described his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, ‘No Colours or Crest’ his wartime experiences in Albania and Poland as a Special Operations Executive agent, and Alms for Oblivion, his post-war experiences in Bali and Lombok. Before his death he produced an autobiography in 1990 called ‘The Forms of Memory’.

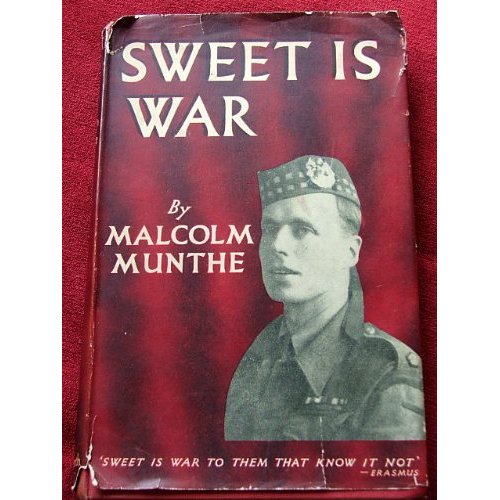

Malcolm Munthe – replacement Rifle Company 2IC

Malcolm Munthe (30 January 1910–24 November 1995) as an Officer in the Gordon Highlanders in 1939: He was sent to Finland with anti-tank munitions by the War Office as an advance party for the British volunteers, the Atholl Highlanders.

Another of Wingate’s officers was Malcolm Munthe. Born in 1910 and 29 years of age on the outbreak of WW2, Munthe was of Anglo-Swedish origins and had joined the British army as war broke out. He was assigned to the Gordon Highlanders for no other reason than his first name’s Scottish roots and was immediately commissioned as an Officer. Almost immediately after the Winter War broke out, he was recruited by the War Office for special operations in Scandinavia due to his Swedish background. . This was an irregular operation set up well before the establishment of the Special Operations Executive and Munthe was sent off to Finland to arrange the supply of munitions to the Finnish Army, carrying with him some experimental explosive devices. He was also to act as a one man advance party for the British volunteer unit, the Atholl Highlanders and he was almost certainly the first British soldier to make it to the Finnish fgront-lines, a story he recounts in his wartime autobiography, “Sweet is War.” In his own words…

“… I was to instruct some Finns under a lieutenant, whose name was Antila, in our anti-tank devices. We went west to Rovanjemi, and for some days to Kemijarvi, and then onwards by sledge. We were near a lake, beyond which were the Russian lines. I never saw a battle while I was there. Antila spoke no English, but we conversed to the best of our ability in Finnish-Swedish. His ski patrol was to be used for special raids to harass the enemy lines.

We slept fourteen in the tent, a circular contraption strung up on a central stovepipe, which carried away the smoke from the wood-burning stove in the middle of the floor. Christmas-tree branches covered the ground; they gave out a delicious smell when the place grew hot. We lay, feet to the middle and heads to the tent wall, with the equipment and rucksack of each man next to his head. I was put between Antila and his second in command, who was a sergeant. It was a tight fit. As I roll around in my sleep, I used to fling out an arm and hit one or other of them, but luckily Antila was just as bad. When we woke at reveille the appalling muddle would have to be straightened out.

Antila was sturdy, with thick dark hair and a permanent grin on his face. I imagine he was only a little older than I and it soon became obvious they had orders to coddle me. I was never allowed to accompany them on raids and was generally protected from even the mildest dangers. I spent my time making “clams” to blow up tanks. “808″ or “plastic” was the explosive used for these charges, with a block of guncotton to hold the detonator and fuse. The whole was then wrapped in a piece of mackintosh, proof against damp, and fitted with magnets so as to make it cling, clam-like, to the tank. The tent was redolent with a smell of almonds and geraniums emanating from the explosives, and I got rather bored with sitting cross-legged on my blankets and gradually covering it with neat little rows of these samples of my handicraft. When I protested, Antila patted my hair and asked with a superior air, “Want to die young?”

One freezing cold day after a particularly severe air raid out of an icy blue sky, I was sent back to Kemi, where a charming, spirited lady of the Swedish Red Cross drove me around in her lorry to some first-aid centres and field hospitals. She spoke excellent English. At one of the posts she introduced me to a Swede who was roaring down the telephone. “You must send them along to us more or less straightened out; otherwise, when they arrive here stiff, we have to spend hours limbering them up again before we can get them to fit into the coffins.”……

“Malcolm Munthe’s Sweet is War is a war memoir that reads like a novel. From a lovelorn London youth we follow Munthe through the banalities of boot camp to the British volunteer battalion sent to Finland to fight the Russians during the Winter War. Caught up in the fall of Norway, the wounded Munthe makes a heroic trek to the safety of neutral Sweden, preparation for his work as ‘Red Horse’, the ubiquitous director of resistance against the Nazis in Scandinavia. From the headquarters of covert operations in London, the young major moves out to North Africa to prepare the ground for the invasion of Sicily and the long hard struggle to liberate Italy. Malcolm Munthe knew well the casual brutality of war, its monstrous waste and random cruelty. He passed through ordeals which tested his sense of humanity to the full. Yet he retained his delight in the irony, comedy, beauty and heroic bravery to be found in this world.” This bitter-sweet memoir of the Second World War reads like a real life version of Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy. Mr Munthe, who had been a page in the Swedish court as a boy was one of those few survivors of the way of life of pre-1914 Europe. His youthful war adventures are consistently farcical, yet take place amidst the horrors of war. The result is a gripping book, sure to appeal even to those who do not usually read war memoirs.

Munthe was a British soldier, writer, and curator, and son of the famous Swedish doctor and writer Axel Munthe (physician to the Swedish royal family and author of “The Story of San Michele”) and his second wife Hilda Pennington-Mellor (an English society lady whom Axel met and married early in the 1900s). Brought up between the Swedish court, Italy, and Britain, where his mother owned two large houses, “Hellens” in Herefordshire and “Southside House” in Wimbledon, Malcolm Munthe became a British citizen at the outbreak of World War II in order to fight, since he expected Sweden to be neutral throughout the war. In his youthful pre-war years, he studied for a Politics degree at the London School of Economics at the same time as he ran a boys’ club in a deprived quarter of Southwark, preparing himself for a career in the Conservative Party and taking part in the social round of debutante balls and London clubs. In 1939 he was offered the comparatively safe Tory seat of East Ham South, but the war intervened and he declined a political career to enter the military. He would end WW2 as a Major, winning the MC for bravery in the process.

Later recruited to the Special Operations Executive, he worked behind enemy lines in occupied Scandinavia – both in Norway and Sweden – as a spy and saboteur, famously blowing up a Nazi munitions train only miles from his own family home in Leksand, Dalarna. After a harrowing escape, recounted in his wartime memoir “Sweet is War”, he was put in charge of SOE’s activities in Southern Italy, where he participated in the Anzio landings. In Scandinavia, Major Munthe had established a network of “Friends” which he called the “Red Horse”, in imitation of the Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel. In Southern Italy, he took the mimicry further, dressing as a (large) old lady to smuggle a radio transmitter past Nazi lines and coordinate SOE activity in the occupied zone. Munthe was also instrumental in the rescue of liberal philosopher Benedetto Croce and his family, held captive in Sorrento, and their flight to Capri where his father Axel Munthe’s house Villa San Michele provided shelter.

After the war, Major Munthe continued to work in the military, and became active in social projects (described in his book The Bunty Boys). In 1945, he married the Right Hon. Ann Felicity Rea (born 15 January 1923), whom he met through her father Philip Russell Rea, 2nd Baron Rea, who was personal staff officer to Brigadier Colin Gubbins (the Head of SOE), and later leader of the Liberal party in the British House of Lords. After an abortive attempt at a political career with the Conservative Party, Munthe re-directed his work towards maintaining the family homes in England, Sweden and Italy. He sold his father’s remaining properties on Capri (the Villa Materita, inter alia), and bought the Castello di Lunghezza, a 108-room castle outside Rome. He opened Hildashol, the property Axel Munthe had built for his wife Hilda in northern Sweden, to the public, and did the same for Hellens and Southside House in England under the auspices of the Pennington-Mellor-Munthe Charity Trust, now (2007) chaired by his eldest son Adam John Munthe. Munthe dedicated his later years to running those properties, and writing, including a history of Hellens, Hellen’s, Much Marcle, Herefordshire and the Special Forces Club.He died at Southside House in November 1995.

Munthe had arrived in Finland in December 1939 and would fight with the Finns until March 1940, initially attached to a Finnish unit where he made magnetic anti-tank mines, he was soon attached to a Finnish Army training unit where soldiers were instructed in how to use the new British-supplied explosives. On the arrival of the Atholl Highlanders in Finland, Munth joined the unit where he was initially assigned to training the supernumeraries. After two weeks Wingate assigned him as a Rifle Company 2IC, replacing a casualty, after which he became a Rifle Company CO. After fighting with Wingate’s raiders on the Karelian Isthmus in spring 1940 and being wounded in action himself, he would be evacuated as far as Bergen in Norway where he would be caught up in the German invasion. He would escape from Norway to Sweden and eventually make it back to London, where he would go on to join SOE. After operating in North Africa and Italy, he would participate in the Anzio landing in early 1944, before being transferred back to Finland as SOE Liaison Officer for the Allies, attached to the Finnish Military Headquarters at Mikkeli where he would help coordinate assistance to the Polish Home Army.

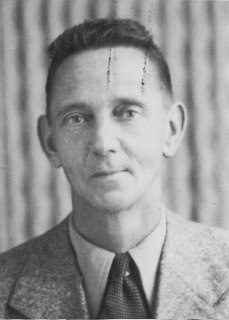

Major Derek Tulloch – Battalion 2IC

Donald Derek Cuthbertson TULLOCH (b. 28 April 1903, died 3 July 1974)

The only Officer that Wingate actually approached and asked to join the Atholl Highlanders was his old school friend, Captain Derek Tulloch. Tulloch had known Wingate from as long ago as their days at Charterhouse School, they had studied at Woolwich (the Royal Artillery School) over the period 1920-1922 together and had fox-hunted together for years. Tulloch was perhaps Wingate’s closest friend and when approached, he immediately agreed to Wingate’s request to become 2IC of the Battalion. War Office approval was immediately forthcoming. Promoted to Major on accepting the position, Tulloch led the first party on the journey to Finland. He would serve as 2IC under Wingate for the remainder of the Winter War and was on his return to the UK awarded the MC (Military Cross) and shortly afterwards (in 1941) promoted to Temporary Lieutenant Colonel. As with Wingate, fighting in Finland with the Maavoimat would give Tulloch many of the ideas and much early experience in operations behind enemy lines and in the logistical necessities inherent in such operations.

Donald Derek Cuthbertson TULLOCH (b. 28 April 1903, died 3 July 1974) was the son of Lieutenant Colonel D. F. Tulloch. He passed out from the RMA Woolwich Royal Artillery in 1923 and was promoted to Lieutenant in 1929, Captain in 1936 and Major in 1940. He was awarded the MC in 1940 and promoted to Temporary Lieutenant Colonel in 1941, Temporary Brigadier 1943 and served with the Chindits over1943 – 1944 (where he would serve as Chief-of-Staff under Wingate). He was awarded the DSO in 1944, promoted to Colonel in 1947, then Temporary Brigadier RA Brigade Southern Command in 1952. He served as ADC to HM the Queen and ended his military career as a Major General and C-in-C Singapore in 1954. He was awarded the CB in 1955. Before he died he wrote a somewhat hagiographical biography of Wingate, “Wingate in Peace and War” (1972).

CSM Charlie Riley – “A” Company – Company Sergeant Major

“A” Company CSM Charlie Riley was a New Zealander – actually a Cockney born in London’s Tower Hamlets in November 1893 who had first arrived in New Zealand in 1913. Although a keen student, Riley had to leave school at 15 to support his family and spent some tedious months in the counting-house of a tea merchant until “an army recruiting sergeant thought I would make a good soldier,” and offered him the traditional King’s shilling to enlist. The next five years were spent with the Royal Field Artillery at Woolwich Arsenal, until “the inside and outside of a fourteen pound gun, down to the last split pin, became as well known as one’s regimental number”. On his discharge at age 21 Riley resumed his childhood passion for ships and the sea. As an ordinary seaman he worked on a succession of tramp steamers, eventually carrying Italian emigrants to New York. Returning from one such voyage in April 1912, his ship encountered the floating wreckage of the Titanic. When “cold voyages across the Atlantic” lost their appeal, he signed on board the SS Tainui for Australia and New Zealand and was paid off in Wellington, New Zealand in April 1913. There he joined the passenger steamer Westralia, “a very happy ship” which shuttled across the Tasman and around the coasts of both countries.

Charlie Riley circa 1938: Riley must have seen more battlefield experience than almost any other New Zealand soldier, was several times wounded and decorated, and was also a notoriously militant organiser of the unemployed during the 1930s.

His mother’s illness brought Riley back to the UK at the inauspicious time of July 1914. Upon the outbreak of war his ability to ride a horse saw him enlisted as a trooper in a heavy cavalry regiment, the Prince of Wales 3rd Dragoon Guards. After three months’ training at Canterbury in Kent, the regiment was sent to the first battle of Ypres where Riley would spend the next two years engaged in heavy fighting, eventually attaining the rank of Sergeant. “We had a gruelling time up there because in the winter time, 1914, 1915, [those years] were vile. We only had ordinary trenches about three feet deep and there was often two feet of water in them and we had ten days in and ten days out. ….. ‘We were in St Julian, that the soldiers called Sanctuary Wood, when the first lot of Canadians got the effect of the gas that the Germans had put over in shells. We were in reserve to the Canadians so we brought them out and… they were all as green as grass from the chlorine…. after a while the Germans gave up using gas. It didn’t work always because they quite often got it back.”

“In one attack we were unfortunate. We met up with a regiment of Prussian guards and they were all huge fellows… I remember going over the top, we met them about halfway and I saw one fellow coming at me so I was ready with the rifle and bayonet. I happened to slip just as I got in front of him. He took a lunge at me but he missed too so up I got quickly and into him, but before that his bayonet just nipped me in the arm, in the muscle.” After emergency dressing in the field, this wound became infected with tetanus and after some time in a hospital in France, Riley was invalided to Britain to make room for more urgent cases.

Discharged from the army as unfit, the resilient 23-year-old became a civilian gunner’s mate on an armed merchantman plying between Britain and South Africa. Towards the end of 1917 he sailed from Port Said to New Zealand on the SS Arawa, repatriating some 800 wounded New Zealand troops. There he was paid off, but “in view of the fact that I had a re-examination and my arm was all right, I had to rejoin and carry on. This time I enlisted in the Mounted Rifles. I went into Featherston Camp and I went off overseas with the 35th reinforcement and arrived in time for the final of the battles in Palestine.” After his final discharge in February 1919 Riley studied engineering at Canterbury University but failed to complete his qualification due to illness (perhaps a form of delayed shellshock). Instead he became a goldminer, and found work as a shot-firer in the West Coast Waiuta mine. By 1930 he was married and living in Christchurch but the onset of worldwide depression meant there was, “no work for a skilled gold miner with a licence to use explosives. My savings vanished within a year.”

Riley had by now become politically active on the left, first with the Labour and then the Communist Party. He became an organiser of the huge numbers of his fellow unemployed workers under the aegis of the Christchurch Unemployed Workers’ Movement. “We used to have our meetings outside in Victoria Square, Christchurch, and we built up a nice organisation… We had illegal demonstrations and so on, we fought the police, we had to. We had to take to the streets to make ourselves known. Oh, I’m well known down there (in Christchurch).” Over the next few years Riley took part in the 1932 tramways strike and accumulated 28 criminal convictions. Following the passage of the extraordinarily repressive Public Safety Conservation Act he was classed as a “rogue and a vagabond” and along with several other leaders of the unemployed, sentenced to a year’s prison. “After I’d been there ten and half months, they asked me if I would go out on probation. I said no, you’ve kept me here this long, I might as well see it out – I did.’”

In 1934, divorced and desperate for work, Riley made his way to Sydney, a city he knew from his seafaring days, and returned to gold-mining, first in Cobar, NSW and then Tennant’s Creek, NT, putting his expertise as a skilled miner and expert in explosives to use. In both mines he was lucky, his crew striking rich seams of ore and earning bonuses of 80 pounds a month each. “From poverty to affluence, it was a good feeling.” Isolated in remote mining camps, Riley spent his off-shift hours reading, thus learning of the rise of fascism in Europe, and especially of Hitler’s ruthless suppression of German trade unions along with Jews and other enemies on the left. The Australian miners and other unions raised funds for their support (“even poverty-stricken men gave their sixpences”), and sympathetic German seamen were secretly recruited to carry large sums to the underground resistance movements.

Riley (3rd from left) and Australian members of the International Brigades arriving home from the Spanish Civil War.

One day, lying on his camp-bed under canvas in the searing heat of Australia’s Northern Territory, Riley heard on his radio that on the far side of the world Franco and his fellow Spanish generals had launched a revolt against their country’s government and were being supported by the world’s fascist leaders. “That Hitler and Mussolini and the Spanish generals had begun attacking Loyalist Spain was about the last straw for us.” Within days he and a mate took the long and risky trek to Darwin, then returned by ship to Sydney, this time with “a small fortune in my pocket”. To save their funds, the two men signed on as firemen with a ship carrying wheat to Britain and after their discharge in Cardiff, the “two wild colonial boys took a first-class carriage to London”. There they made contact with recruiters for the International Brigades and as part of a group of over 100 volunteers, including a number of French Foreign Legion veterans, Riley made the grueling 14-hour trek across snowbound tracks through the Pyrenees, evading French machine-gun posts and searchlights. “Sometimes you had to run and drop down when the searchlights were in the vicinity, but anyhow, we made it and we arrived.”

In Catalonia Riley was enlisted in a mainly British unit of the XV International Brigades, and was soon thrown into action in the battle of Teruel. With characteristic offhandedness, Riley recalls the conditions as “pretty tough. The Germans and the Italians were far better off than we were. One thing we lacked was sufficient artillery and they had more aircraft than we did, although we were supplied from time to time with Russian bombers and they used to do a lot of good work.” Over the next 20 months Riley took part in the battle of Brunete, the later Republican offensive across the Ebro River and the subsequent disastrous withdrawal. In his 200-page memoir of the civil war (held in New Zealand’s Alexander Turnbull Library) he records his fascination at the differences he found between the idealistic Republican army and the British army in WWI. “There were no batmen or officer’s servants in the Republican Army; even the CO cleaned his own boots.” He is full of admiration for the women and children of republican Spain, and for regular Spanish troops such as the very youthful snipers. “Many of them were little taller than their rifles, but this did not prevent them from commanding respect.”

As a trained soldier with a knowledge of explosives and artillery, Riley gained the title of “shock brigader”, awarded to those with qualities of both military and political leadership. Already fluent in French, he acquired a useful knowledge of Spanish and trained the younger troops in the use of weapons and explosives. He also appears to have volunteered for some of the most dangerous actions of a very desperate war. “The night patrols were the more exciting of all night duties and … I must confess I used to enjoy taking part in patrol work near the lines. This was probably a stray heirloom inherited from the Great War period when in various sections of the Western Front, I seemed to enjoy (at the time anyway) creeping across No Man’s Land with other adventurous spirits loaded with hand grenades”. Riley’s memoir records in detail the various types of weapon, command systems and military tactics he observed, most of them new to him since the Spanish Civil War served as an important testing ground for the world war to come. “In the early fighting stages,” he subsequently recalled, “there was less than one rifle between each six defenders and many of the weapons were generations old. In the earlier days of the Rebellion, the antiquated Spanish Mauser held sway and there were many much more antiquated blunderbusses, carbines and flintlock pistols that did sterling work on the barricades, and which… might have found honoured resting places in any museum.” By the time Riley arrived in Spain, however, modern weaponry was arriving from the few foreign countries which officially supported the Republic, and he was issued with a Czech-made light machine gun with which to defend his column of infantry. “If planes came down, you took a potshot at them and got rid of them. They often flew low and you didn’t miss, you hit them somewhere and quite often a few were brought down.”

Sergeant Charlie Riley, New Zealand Army, April 1943

The Republican forces were generally less well equipped than their opponents and were often forced to improvise their weapons and strategies. Riley’s experience with explosives in the mines meant he was called upon to take part in the exceptionally dangerous work of close-quarter anti-tank warfare. “We carried about eight anti-tank bombs each. We used to get close to (the tanks) and throw them under the tracks and once they went off you’d see that the track had come off. They were immobilised then and all you had to do was find a place where you could throw another bomb in and kill the crew… If you get close to them they can’t shoot you, because their line of fire is beyond you.” No more than a dozen New Zealanders fought with the International Brigades, and Riley appears to have met only one other, a fellow seaman named Bert Bryan, from Timaru. The two met in combat on the River Ebro, the last major action of the International Brigades. “There was one place that was giving the Republican officers a headache and that was the Mora de Ebro bridge, so they sorted out half a dozen miners and I was among them and we mined the middle of the three spans.” Two nights later, the Republican fighters heard the rumbling of Italian tanks massed on the far side of the river. “The fuses were all ready and we just set them off. The bridge was half full of tanks when up she went and the three spans with it…. They never crossed the Ebro River, not while we were there.”

Soon after this success, however, Riley’s unit faced a fierce counter-attack from Italian infantry, and he was hit by machine gun bullets and shrapnel. “After being wounded in the head, face and left jugular artery, both shoulders and arms, I must have presented a pretty sight. One side of my face was a mass of congealed blood, the khaki beret which I held to my neck being saturated with the thick bloody mass… I still remember walking up a hillside to contact the dressing station which lay on the other side of the hill.” The still-conscious Riley was taken to Valls Hospital where his wounds became infected. “Only by long and careful treatment by the American staff and my Spanish nurses, Carmen and Tina, did I manage to retain my right arm.” That treatment included an emergency transfusion of blood donated by one of these nurses. Fortunately for the critically injured Riley, the quality of medical care available to Republican troops was generally very high. Volunteer doctors and nurses as well as combatants had arrived from around the world to support the Republicans, and together with native Spanish staff they pioneered battlefield medical techniques, such as the use of emergency blood transfusions, that would soon become routine. This treatment was provided under the worst imaginable wartime conditions and as Riley was transferred to a succession of hospitals, he witnessed a number of bombing raids on medical facilities. “Some time after I had left Valls, the hospital was bombed by insurgent air squadrons. Nevertheless it had remained untouched until almost the very end (of the war) for the reason that Franco had a country estate there.” At the time of this bombing, Riley notes, the hospital had a full complement of 400 patients.

After a month at Valls, with his right arm slowly recovering, Riley applied to rejoin his brigade but the hospital’s medical officer transferred him to the International Brigade’s Base Hospital at Mataro. There he met a number of Australian and New Zealand nurses, probably including Rene Shadbolt and Isobel Dodds who had been sent by New Zealand’s Spanish Medical Aid Committee. In late 1938, shortly before all International Brigaders were formally withdrawn from the front, he and other seriously wounded men were repatriated on board a Red Cross train to Paris. Still with his right arm in a sling, Riley arrived at London’s Victoria Station where he promptly weighed himself and noted the rigors of the past 20 months’ fighting. “The pointer registered at 8 st 7 lbs, which showed a loss of 2 st 7 lb.”

Riley was still in Britain when WW2 broke out and was preparing to return to New Zealand where he intended to rejoin the New Zealand Army. He, like many other left-wingers who were not out and out communists who toed the Soviet Party line regardless, was outraged by the Soviet attack on Finland. He had attempted to join the ANZAC Battalion in December 1939 but had been turned down as “unsuitable”, probably due to his political beliefs which would not have gone down well with the more conservative New Zealand volunteers in the UK, who came from rather more middle-class backgrounds. Undeterred and still in the UK in February 1940, he immediately applied to join the Atholl Highlanders at the age of 46 (while claiming to be 39). He somehow made it through the medical inspection and Wingate, on hearing of his experience in WW1 and the Spanish Civil War, immediately interviewed him. Wingate was somewhat of a maverick himself and he made no bones about caring not one whit for Riley’s leftist political convictions. Without further ado he appointed Riley Company Sergeant Major of “A” Company where he would be under the command of Peter Kemp. Oblivious to the politics of the Spanish Civil War, Wingate’s reason for putting him under Kemp was stated as “you chaps both fought in Spain, no doubt you have a lot in common….” Nevertheless, despite their political differences, both men got on well and Riley served capably under Kemp throughout the Winter War. Wounded in action in the fighting in Finland, Riley would recover and on his return to the UK, would enlist with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in the Middle East.

Outside Tobruk he would be wounded a fourth time, once again surviving to be repatriated. As the narrator says in “Man Alone”, John Mulgan’s classic New Zealand novel, “there are some men you just can’t kill”. Back in New Zealand, the almost indestructible leftwing battler remarried, outlived his second wife and carried on alone in his Naenae state house until his death in 1982. Interviewing him in 1972 at the age of 80, Ray Grover recalls that “there was nothing military about him, but he had the attitude of a ranker, a chirpy little Cockney guy.” Unlike many of those who offered their lives to the Spanish cause only to see Franco impose decades of repression, Riley looked back on his actions without regret. “There was no bitterness in the man at all.”

Captain Allison Digby Tatham-Warter – “B” Company 2IC

Major Allison Digby Tatham-Warter DSO (26 May 1917 – 21 March 1993)

Born on 26 May 1917, Captain Allison Digby Tatham-Warter attended Scaitcliffe school in Surrey with his brother John, where they became friends with Peter Wilkinson, who went on to have a distinguished career with the Special Operations Executive in the Second World War. He later attended Wrekin College and then the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst where he became a talented horse-rider and won “The Saddle” as best horseman in his class. He joined the army in the late thirties and was commissioned as a second lieutenant on 28 January 1937. He was expected to join the Indian Army, but during an obligatory year-long attachment with a British regiment serving in India (in this instance the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry) he decided to remain with them and was officially transferred to the regiment in 1938. Whilst in India Tatham-Warter further demonstrated his horse-riding and hunting skills. During a pig sticking competition he once killed three wild boar that each averaged 150 pounds (68 kg) and stood 3 foot (0.91 m) tall. On another occasion he killed a tiger that was stalking the group he was with. He was still serving with the Ox and Bucks in India but was on leave in the UK when war was declared in 1939. Tatham-Warter was promoted to Lieutenant in January 1940 and after volunteering and being accepted into the Atholl Highlanders, he was made an acting Captain and appointed 2IC of “B” Company under Major “Mad Jack” Churchill.

His first experience of combat came in the Karelian Isthmus offensive of Spring 1940 where Wingate put “B” Company in the vanguard of the drop, believing that both Churchill and Tatham-Warter were “thrusters”. Tasked with seizing two key road junctions and a critically important bridge, the Atholl Highlanders were to seize these at dawn on the first day of the offensive. “B” company would advance straight from the glider landing zone to the bridge while the rest of the battalion took the two road junctions. The initial landings were largely unopposed and the various Companies formed up quickly. Tatham-Warter set up the Battalion rendevous using smoke and lamps, before the order to move off came just after 6am. B Company was in action almost at once; ambushing a small Red Army recce group near the drop zone before moving off through the woods toward the river road, with each platoon taking turns to lead. Tatham-Warter led the vanguard one mile from the dropzone to the bridge at a cost of only one killed and a small number of men wounded whilst having killed something like 150 Russians. He later remembered that “for me, the best moment of all was after our platoons had overrun the Russians guarding the bridge and I stood on the embankment to the bridge watching as they moved into position to cover the approaches from the north and the bridge itself.”

After the bridge had been taken, they were joined by supporting units from the Battalion, including four anti-tank guns and two 81mm mortar teams. Red Army units began counter-attacking almost immediately in an attempt to recapture the bridge and the fighting became heavier by the hour. During the fighting that followed, Tatham-Warter could often be seen calmly strolling about the defences, seemingly oblivious to the constant threat of mortar barrages and rifle fire. Choosing to wear his beret in place of a helmet and swinging his trademark umbrella as he went, Tatham-Warter, no matter how desperate the situation became, never failed in his ability to remain unconcerned and to encourage those around him. Even old hands had become somewhat disheartened at the sheer strength and size of the Red Army attacks but the gloom was lifted instantly at the sight of Tatham-Warter leading a bayonet charge against Russian infantry who had dared to enter Atholl Highlanders territory; carrying a pistol in one hand, madly swinging his umbrella about his head with the other, and now sporting a bowler hat on his head – which he had obtained from God knows where – doing his best to look like Charlie Chaplin. On another occasion later that same day he used the rolled up umbrella to in-effect disable a Russian armoured car, simply by thrusting it through an observation slit in the vehicle and incapacitating the driver, after which the rest of the crew were killed and the vehicle captured and used as a machinegun post. Tatham-Warter later revealed that he carried the umbrella because he could never remember the password, and it would be quite obvious to anyone that the bloody fool carrying the umbrella could only be an Englishman.

The Padre drew Tatham-Warter’s attention to all the mortars exploding everywhere, to which came the reply “Don’t worry, I’ve got an umbrella.”

During the battle, the Battalion Padre, was trying to cross the road to visit the wounded in a depression in the ground that provided at least a little cover. He made an attempt to move over but was forced to seek shelter from intense Russian mortar fire. He then noticed Digby Tatham-Warter casually approaching him. The Captain opened his old and battered umbrella and held it over the Padre’s head, beckoning him “Come on, Padre”. The Padre drew Tatham-Warter’s attention to all the mortars exploding everywhere, to which came the reply “Don’t worry, I’ve got an umbrella.” Shortly afterwards Lieutenant Patrick Dalzel-Job was sprinting over an open area he had been ordered to hold when he caught the sight of Tatham-Warter visiting men who were defending the sector, holding his opened umbrella over his head.

Dalzel-Job was so surprised he stopped dead in his tracks and suggested to the Captain “That thing won’t do you much good”, to which Tatham-Warter replied, after staring at him with exaggerated shock, “Oh my goodness Pat, what if it rains?” Rifleman George Lawson was running back to the Company HQ position for ammunition when he saw Tatham-Warter coolly walking around and directing men to fresh positions. Upon noticing Lawson he asked him what he wanted, and was enlightened, so the Captain advised him to “Hurry up and get some and get back to your post soldier, there are snipers about”, seemingly unconscious of the fact that he himself was a very obvious target. Such untroubled and good humored gestures doubtlessly contributed greatly to the morale of the defenders, and kept spirits high even when the fighting was at its fiercest.

Throughout the battle, Tatham-Warter was a model of leadership and continued to enliven spirits with his eccentric sense of humour, whilst also being tireless in making sure that the defences were as solid as they could be under the circumstances. The constant Close Air Support called in by the Finnish Army Fire Control Team attached to the Company also assisted the defenders considerably as the Red Army attacks grew increasingly desperate. Not having fought in a battle before and choosing an unusually violent one for his debut, Tatham-Warter asked of Major Churchill “I would like to know if this is worse or not so bad as the other things you’ve been in?” Churchill replied that it was hard to say as some things were worse, whereas some weren’t; they still had food and water, but were getting low on ammunition. The best thing, Churchill told him, was the air support – he’d never imagined it could be so effective. In constant touch with Battalion HQ by radio, they received the good news that evening that the Maavoimat’s 21st Armoured Division was advancing rapidly and had already reached the first road junction held by the Battalion and that Maavoimat Artillery was now within range.

Digby Tatham-Warter in later years

This was just as well as the trapped Red Army units were increasingly desperate to escape from the one side, and to recapture the bride from the other. With artillery support now available, most of the night was spend hunkered down calling in artillery strike after artillery strike on waves of Red Army infantry. As dawn broke, the Red Army attacks reached a new frenzy, as did the calls for artillery and close air support. “B” Company held, albeit with many killed and seriously wounded and like the majority of the defenders, Tatham-Warter received several wounds, including minor shrapnel cuts to his posterior, which he shrugged off. Late that afternoon, the leading elements of the 21st Panssaridivisioona reached the bridge and immediately passed across, attacking the Red Army units on the other side of the river. “B” Company continued to guard the bridge for the next 2 days as Maavoimat units passed by in an endless stream. The Red Army front had been smashed apart and the road to Leningrad was open as long as the attackers momentum was maintained.

Tatham-Warter would recover from his minor wounds and, like the rest of the Atholl Highlanders, go on to fight in a series of raids behind the Red Army lines before returning to the UK. He would return to Finland in late 1943 as a Major commanding a Company of the British Army’s 1st Airborne Division where he would participate in the airborne landings that heralded the start of the invasion of Estonia. His last major action would be the drop of the 1st Airborne Division, the Maavoimat Parajaeger Division and the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade into Warsaw to fight alongside the Polish Home Army in the Warsaw Rising. Once again, he would be there to welcome the Maavoimat’s 21st Panssaridivisioona as they broke through the German defences to relieve Warsaw. He is recalled as a particularly severe but inspirational commander of his men (few of whose names he apparently knew, nor was particularly interested in). The soldiers were there to follow and to fight and he, above all, to lead. His officers (mainly drawn from similar backgrounds as his) were expected to emulate his attitudes and standards. Derek Tulloch, Tatham-Warter’s Battalion 2IC in Finland, once remarked (probably in Digby’s defence): “But every battalion needs a Digby!” Officers, and many of the men, who served with and under him would almost certainly agree

OTL, Major Tatham-Warter volunteered for the Parachute Regiment in 1943 and in September 1944 he accompanied the 1st Airborne Division to Arnhem during Operation Market Garden. In the ensuing battle he was part of the small force that actually reached Arnhem road bridge and defended the northern end for several days before being overrun. Although captured by German forces he quickly escaped and contacted the local resistance. Over the next month he organised dozens of survivors from the battle who were in hiding behind enemy lines, before leading them to freedom south of the Lower Rhine. For his part in the battle and escape operation he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. After the war he moved to Kenya where he became a hunter and in a somewhat eccentric manner ran a safari park, becoming a pioneer of camera-shoots. He died in 1993 at the age of 75.

RNVR Sub-Lieutenant Patrick Dalzel-Job, Platoon Commander, “B” Company

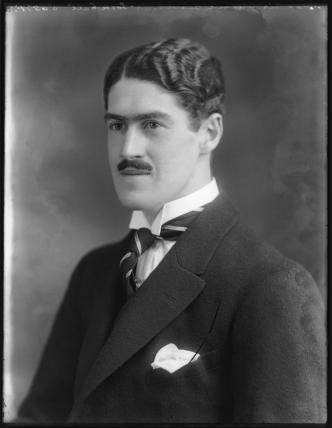

Patrick Dalzel-Job as a young and recently-commissioned Naval Officer

Patrick Dalzel-Job was born near London in, the only son of Captain Ernest Dalzel-Job, who was killed in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. He suffered ill health as a child and his widowed mother took him from Hastings to Switzerland, to regain his strength. Here, Patrick became accomplished at cross country skiing and then ski jumping and taught himself to sail on a lake near the French border whilst studying navigation by correspondence course. He returned to Britain in 1931, built his own schooner, the Mary Fortune, and spent the next two years sailing around the British coast with his mother as his crew. In 1937, they crossed the North Sea to Norway and spent the next two years making studies of the west coast and the fjords, channels and islands and sailing as far north and east as Petsamo, in Finland. He and his mother were accompanied by a blue-eyed little Norwegian schoolgirl named Bjørg Bangsund. The Norwegians were most hospitable and Patrick soon became fluent in their language.

In late August 1939, a radio broadcast persuaded Patrick and his mother that war was imminent and they returned to England. Patrick was commissioned into the Royal Navy on 8 December 1939, and requested a posting as far north as possible. He was appointed navigating officer on a target towing tug working from Scapa Flow in Orkney from January 1940.

Ever eager to return to Norway and the north, Dalzel-Job applied in writing to join the Atholl Highlanders on reading of the need for Volunteers for Finland in the newspapers. His application had been discarded (a naval officer, after all) when Wingate happened to come across it as he was looking for a scrap of paper on which to jot some notes – almost at the last moment as it was on the last day before Wingate was to leave for Norway. That evening, Dalzel-Job received a telegram ordering him to Glasgow where he was to report on board the cruiser HMS Southampton. There he was to join Lt-Col. Wingate and the last contingent of the Atholl Highlanders, who were to travel to Finland via the northern Norwegian port of Lyngenfjiord. He made it with only a couple of hours to spare and on 12 March they sailed together with 4 cargo ships carrying war materials and a small escort of destroyers.

It soon became evident that Dalzel-Job’s knowledge of the area and weather conditions was invaluable as the naval ships had no detailed maps of the area where they were to be transported to. In addition, on arrival at Lyngenfjord it was found that the limited docking space available was tied up with cargo ships unloading military supplies around the clock and there was simply nowhere to unload the troops. Wingate asked Dalzel-Job’s advice, and immediately accepted his suggestion that the soldiers could land from the cruiser using the local fishing boats (skøyter, which Dalzel-Job referred to as ‘puffers’). With his colloquial command of Norwegian, Dalzel-Job soon had the local fishermen organized and the men were taken ashore in these boats on 14 and 15 March 1940. He was later to say “I called them puffers because as a child in the West Highlands, all our goods used to come up from Glasgow in little round ships called puffers. They were built like that to come through the Grand Canal and the Norwegian word for these boats was skøyter. Well, of course, no British people would say skøyter so I called them puffers and Wingate thought that was the Norwegian name and official reports said “local boats called puffers” – but they were called puffers only by me.”

Sub-Lieutenant Dalzel-Job with the Atholl Highlanders, Finland, 1940. “By the end of summer, 1940, I had commanded a Platoon in the glider landings on the Karelian Isthmus in the Spring, and then been on four deep penetration missions behind the Red Army’s lines attacking rear area units and supply dumps. I had jumped out of an aircraft using a parachute twice, been in so many firefights I had lost count and half my men had been killed or wounded in action. I had fought alongside the Finnish soldiers of Osasto Nyrkki and for the rest of the war, whenever things got rather challenging, I would say to myself, “What would Osasto Nyrkki do here” and the answer was usually the most outrageously aggressive and daring solution you could think of. So that’s what I would do.

With his knowledge of Norwegian, Dalzel-Job proved an invaluable aide to Wingate in getting the men and equipment off loaded and organized on-shore. His knowledge and experience of the climate and conditions also led Dalzel-Job to rapidly organize with the Norwegians and later with the Finns for the provision of more suitable clothing and equipment for the British volunteers even prior to their moving out on a large convoy of overloaded Finnish trucks. A week later the Atholl Highlanders were in Lapua and being put through Finnish Army training, which Dalzel-Job found an enjoyable challenge. “It was tough, far tougher than I had ever imagined such training would be or could be, but we all learnt a tremendous amount in the shortest imaginable time. There was not a moment wasted and our Maavoimat instructors, many of them recovering from wounds received in the early fighting back in December, kept drumming it in to us that we had to learn fast and that a single mistake in fighting the Russians would get us killed.”

When the Atholl Highlanders moved up to the Karelian Isthmus on the reserve lines, Dalzel-Job was in command of a Platoon within “B” Company under Major Churchill. The Battalion continued to train hard as they manned the rear defence lines and listened to the guns. “The artillery went on day and night and when it crescendoed, we knew the Russians were up to something and we were all on edge a bit. But the Finns were good at keeping us informed as to what was going on and they never showed any doubt as to the outcome. The common refrain was “The Marski knows what he’s doing” and they had an unshakable faith in him, which of course as we all know now was entirely correct. We ended up meeting “The Marski” – even we ended up referring to Marshall Mannerheim by that term – when we left Finland in late 1940 after the peace agreement with the Soviet Union was signed and he turned up for our last parade before we were trucked north to Petsamo (by that time Lyngenfjiord was a bit close to the Germans for us to ship out from). He was certainly an imposing figure with a real presence that you could feel and he spoke excellent English.

Then, I have no idea how it happened but Lt-Col. Wingate somehow got us attached to the Maavoimat’s Parajaeger Division and we trained with them for a couple of weeks and then took part in the big offensive that the Finns launched to retake the Karelian Isthmus from the Russians in Spring 1940. We were carried in Gliders, we’d never heard of using gliders to carry soldiers into an attack before but the Finnish soldiers were all very blasé about it so we just did our training and then when the time for the Op came, we gritted our teeth and climbed in and hung on. The whole attack seemed to take the Russians completely by surprise and the Maavoimat just took them apart chewed them up and spat out the pieces.

Now, I can say that it was “Blitzkrieg” before the Germans showed how it was done to the rest of the world in France in May 1940, but this was a month earlier and the Finns certainly didn’t publicise how they did it but from our part in it, we had a pretty good idea. Of course, when we got back to the UK we had to write up all sorts of reports on what we’d seen but as far as I could tell, they all just disappeared into the usual Intelligence black hole and nothing ever came of them – the British Army certainly didn’t learn a thing although in the Commandos and later in 30 AU we put the Finnish tactics we’d learnt to good use. So did Wingate and Tulloch and Mike Calvert for that matter with the Chindits in Burma, and of course everyone knows about David Stirling and the SAS – and all of that had its origins in the 2 British units sent to Finland and the experience we gained there.

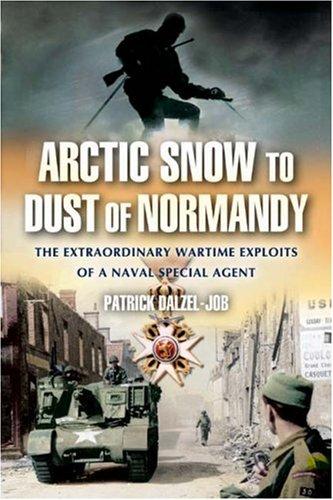

Patrick Dalzel-Job released his memoirs, titled From Arctic Snow to Dust of Normandy in 1991 and died on 14 October 2003, aged 90 years.

After the Spring Offensive, we got pulled out to recover and then we did some more training, this time with the Maavoimat’s Osasto Nyrkki special forces unit – they were the real elite of the Finnish Army and they pulled off all sorts of amazing feats – blowing up the NKVD Headquarters in Leningrad was just one of them – they also took out a whole Russian airfield with hundreds of aircraft – I think that was where Stirling got some of his ideas from, from that raid. Anyhow, we trained with them and then we did a whole series of missions behind the Red Army lines where we were attacking headquarters units and logistical supply dumps and railways and bridges and things deep inside the Soviet Union. We would be flown in and either parachute in or land in floatplanes – the Finnish Air Force, the Ilmavoimat, had a lot of those, and then we would do our mission and usually end up running away from the Russians who would chase us through the forests and swamps, and then we would be picked up or we would exfiltrate through the Red Army lines back to the Finnish side, take a break and then do it again.

Depending on the mission, we could be anything from a small team up to a whole Company and once even the entire Battalion. I found the whole thing rather exhilarating at the time and even though it was dangerous, I never worried about that aspect of what we were doing. No doubt it was the boundless self-confidence of youth. I did feel sorry for the Russian soldiers at times, it was like killing baby chicks a lot of the time but it had to be done. The NKVD rear area troops were different though, they were quite often fairly good and you didn’t want to fall into their . hands either – we had seen the results of that once or twice and after that, we never passed up the chance to take them out. And the Finns had an evil way with booby traps and devices to slow them down when they were chasing us, we put that to good use many times. The Finns were great chaps to fight alongside, not great talkers and their sense of humor was a bit challenging at times but they knew their way round the woods, their fieldcraft was really good and they were superb soldiers. Not much discipline compared to us, and we were no great shakes compared to the regular British Army – in fact the way that we and the 5th Bat Scots Guards operated ended up becoming the modus operandi for units like the Commandos and the SAS later on and that was all picked up from working with the Finns and with Osasto Nyrkki in particular.

“Age of Heroes” – the 2010 movie about Ian Fleming’s 30 Assault Unit.

After his return to the UK from Finland in late 1940, Dalzell-Job would return to the Navy and spend almost two years on ships before going on to become a Commando and a distinguished Naval Intelligence Officer. In June 1942, Dalzel-Job was assigned to collate information about the west coast of Norway. A few months later, Lord Louis Mountbatten, head of Combined Operations, chose him to convey Commando raids there, known as ‘VP operations’, using eight ‘D’-Class Motor Torpedo Boats. From mid-1943 until early 1944, he served with the 12 (Special Service) Submarine Flotilla becoming versed with X-Craft and midget submarines, while taking time to complete parachute training with the Airborne Division. As prospects for major action in Norway faded, Dalzel-Job visited London and discovered 30 AU (Assault Unit) Commando, the field operative unit of the Naval Intelligence Division – Room 30. He transferred to 30 AU under the command of Commander Ian Fleming who was then Personal Assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence.

In this role, and promoted to Lieutenant Commander, he landed near Varreville on Utah beach, Normandy, on D+4 with two Royal Marines Commandos allocated to him, and an unrestricted authority order signed by U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower to pass through Allied lines and assault specific targets in German held territory. In June 1945 he returned to Norway and found the blue-eyed young Norwegian girl (Bjørg Bangsund, now 19) he and his mother had sailed with before the war. They were married in Oslo three weeks later.OTL, Dalzel-Job served with the Anglo/Polish/French Expeditionary Force to Norway from April to June 1940, during which time he disobeyed a direct order to cease civilian evacuation from Narvik. His action saved some 5000 Norwegians for which King Haakon of Norway awarded him the Ridderkors (Knight’s Cross) of St. Olav in 1943. This award saved him from being court-martialed. Brave, reckless and a maverick known for his disregard for authority, Patrick Dalzel-Job was the nearest real life model for James Bond and the release of his war records, protected by the Official Secrets Act for more than half a century, appears to strengthen his position as the “true” 007.

Dalzel-Job ended up working for British Naval Intelligence and was recruited by Ian Fleming to join his undercover 30 Assault Unit, a special force which would race ahead of Allied front-line troops to seize secret German equipment and documents before they could be destroyed. Like Bond, he piloted miniature submarines and could ski backwards. Just as Bond’s independent attitude frustrates ‘M’, so the lone wolf Dalzel-Job had no qualms about disobeying orders. Confidential reports by senior officers show parallels with Bond. “He keeps himself in an exceptionally high state of physical fitness, he can withstand an unusual amount of hardship and exposure,” said one. Another report stated: “An unusual officer who possesses no fear of danger and has been used to living on his own. When the work appeals to him he is a first class officer.”

Second Lieutenant David Vere Stead, Platoon Commander, “B” Company

Nell Vere Stead, sister of David Vere Stead

Another of the “B” Company platoon commanders was Second Lieutenant David Vere Stead. Stead was an Australian from Melbourne, the son of Australian millionaire David Sydney Vere Stead and the brother of the first Australian woman to become a duchess – the former Melbourne socialite, Nell Vere Stead, whose husband, a Navy Commander whose full name was Alexander George Francis Drogo Montagu (known by the courtesy title of Viscount Mandeville but always known as “Mandy”) and who was to become the 10th Duke of Manchester in 1947. Grey Duberly, daughter of local landowners Hugh and Saffron Duberly, recalls that it was at her parents’ house, Staughton Manor, that Nell proved most adventurous. ‘One exciting night, she came to dinner. She had on a dress made of mink or something. After dinner, she dumped it and stepped out – completely naked.’

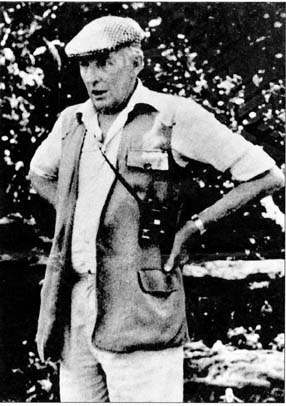

Lieutenant Karl Nurk, “HQ” Company, British Army Liaison Officer to the Finns

Lieutenant Karl Nurk was an Estonian, born in Tartu on 24 June 1904, died in South Africa 28 July 1976. He was the son of Karel August Nurk, a pawnshop owner, and Ernestine Josephine Vastrik and had two brothers, Helmi Nurk and Richard Nurk.

As a 13 year old volunteer, he had been one of the youngest soldiers in the Estonian War of Independence. After Estonia had secured its independence, he had taken part in the fighting against the Russians in Eastern Karelia as a volunteer. He then attended the H. Treffneri Gümnaasium (in Tartu, Eesti) from which he graduated in 1923. He then served in the Estonian War Ministry but in 1924, he decided to embark on adventurous journey into the wider world beyond Estonia. He travelled to France, where he met a fellow Estonian, Evald Marks, who had an unusual plan – to “walk” across the Sahara desert. The Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs website mentions that in 1925, two young men from Tartu, Evald Marks and Karl Nurk, spent some time in Tunisia and that in November of the same year they set off from the city of Gafsa on their 7 month hike through the Sahara Desert. They apparently started out with camels but ended the journey on foot after their camels died (there were also rumors that the two had deserted from the French Foreign Legion but this seems to be fictional rather than factual).

Karl Nurk, an estonian who would go on to become a Colonel in the British Army, with a lion he hunted and shot in Tanganyika

After their successful desert crossing, they spent some time in the French corner of Central Africa as professional elephant hunters (hunting for ivory was fairly lucrative in the inter-war years if you were up to the challenge of successfully shooting enough elephants to make it worthwhile). Later the two continued on to British East Africa, they are recorded in 1928 as having been Estate Managers for the Earl of Lovelace in the area around Babati, Kenya, where the Earl owned coffee estates. In 1934 Nurk once again began to hunt elephants in Tanganyika. At some stage it appears he married an Englishwoman who owned a sizable plantation and thus became somewhat wealthy himself. Back in the UK at the outbreak of WW2, when the Winter War broke out, Karl Nurk visited the Finnish Embassy in London and expressed the wish to go for help in the fight of the Finns against the Russians. The Finnish Embassy referred him to the British Volunteer unit being set up, where Nurk successfully presented himself as a military veteran with experience fighting in Karelia as well as a successful citizen of British East Africa.

Nurk was promptly signed up and commissioned as a Lieutenant. After interviewing him, Wingate attached him to HQ Company, explaining that there were few enough Finnish speakers in the British Army that he would be invaluable as an assistant to Wingate. They also apparently spend considerable time talking about their respective Saharan desert trips, a common interest which gave Wingate a high regard for Nurk. They would work well together throughout the Winter War, with Nurk acting as an Aide to Wingate through to the end of the campaign. Indeed, such was the regard that Wingate held Nurk in that he would take Nurk with him to Ethiopia ater Italy had declared war on Britain and Wingate was sent to Ethiopia, where he would form “Gideon Force” to fight the Italians. Second Lieutenant Nurk would serve with the 2nd East African Irregulars, training Ethiopian Irregular units. In November 1941 he was involved in the conquest of Gondar. In a book published after the war in the UK (1949) about the fighting in Abyssinia, Nurk was repeatedly mentioned by name – at the time, on 21 October 1941 (ref London Gazette) he was promoted to Captain (General List) and awarded the Military Cross.

British Volunteers for Finland – Oath – signed by Karl Nurk and Harold Gibson

After completion of his assignment Abyssinia he was posted to Iran and then in 1942 to Cairo, where he was on the General Staff. In 1944 he was part of the SAS unit sent to Yugoslavia and based on Visi Island, from where they supplied and supported Tito’s forces and carried out raids against the Germans, actions in which Nurk often took part. In one such attack against the Germans Nurk was wounded by a grenade after which he was sent to a hospital in Italy and then to Algeria to recover. In August 1944 he was dropped into southern France behind the front as part of a SAS unit. His unit was in contact with the French resistance movement, and carried out a series of attacks behind the German lines. Roy Farran mentions Nurk a number of times in his recollection of his time in the SAS during WW2, however he is referred to in Phillip Warner’s “The SAS” as a White Russian.

On 13 June 1944 Nurk is mentioned in the London Gazette has having been awarded the DSO and somewhere in this timeframe he was promoted to Major. In 1947, shortly after WW2, Nurk became a British Citizen (Naturalisation Certificate: Karl Nurk. From Russia. Certificate AZ28546 issued 21 June 1947) and in 1949 he was awarded the Military Medal of Haile Selassie 1st Class. From 1949 to 1953 he was part of the British Military Mission in Greece. From 1954 to 1957 military attaché at the British Embassy in Ethiopia he was the British Military Attaché at the British Embassy in Ethiopia, at which time he is recorded as holding the rank of Colonel. After retiring from the military, he lived for some time in the UK, where he had an acting role in the 1965 movie, “The Naked Brigade” playing the role of Professor Forsythe. In 1966 he moved to South Africa where he lived for the last 10 years of his life. Having survived countless adventures, Karl Nurk died on 28 July 1976. He was survived by his wife, Madeleine, and son. His death was reported in the “Voice of Africa” 1976 22 Oct Nr. 1503, p1-2 and in the Free Estonian, Toronto, Canada.

OTL Note: Nurk was a Platoon Commander with the British Volunteers in Finland. He managed to escape through Petsamo by ship to New York, after which he returned to the UK and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant on October 1940 (ref the London Gazette). The service with Wingate in the Winter War is ATL, all else in this brief biography is factual.

Lieutenant Duncan Dunbar Guthrie, Platoon Commander, “D” Company

Duncan Dunbar Guthrie was born in London on 1 October 1911. Prior to WW2 he had been an actor, a journalist and a playwright. His most notable acting appearance was in the 1935 film, “Riders to the Sea” – a photo of the cast appears below (without names unfortunately). He also acted in a further film, “Children of the Fog.” Whilst his beliefs were socialist, Guthrie volunteered to fight in the Winter War and was signed on as a Lieutenant. He would lead a platoon within “D” Company for the duration of the Winter War. After the return of the British Volunteers to the UK in late 1940, Guthrie would join the Royal Canadian Artillery, then transfer to the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry in 1943. He at some stage shortly after this transferred to SOE and as a Captain, led Jedburgh Team Harry, dropping from Tempsford to Central France on the night of 6-7 June 1944. After the war in Europe ended, he was promoted to Major and transferred to SOE in South East Asia and was dropped into Burma to join the Karen guerillas fighting behind the Japanese lines. He broke his leg on landing which effectively ended his participation in the War.

Actors from “Riders to the Sea” – photo from 1935 at the end of filming. Duncan Guthrie is among these but none are named

Shortly after WW2, he became involved in the financial support of medical research. This started in 1949 when Janet, his first child, developed poliomyelitis (Guthrie married Prue Holloway in 1949). This was at a time when progress was being made in the United States in the development of poliomyelitis vaccines, while in Britain, as the late Bill Bradley of the Department of Health said, “The problem of polio in England is – ignorance, impotence and insecurity.” Guthrie alerted society to this problem at the Festival of Britain and with his wife Prue set up the National Fund for Poliomyelitis Research with himself as the Director. Their first headquarters was two tiny dark rooms up three flights of stairs above a fruit shop in Spenser Street, in Westminster. Guthrie deplored the development of palatial offices and large staffs by charities and insisted that money collected for a charity should be spent on its aims. When Director of the NFPR, he had to be persuaded to accept an increase in salary for himself while his wife was doing a full-time job to help support the family of three children.

Duncan Guthrie with his daughter Janet

In fund-raising, Guthrie demonstrated the same fertile and imaginative mind that had engineered his escape from Norway during the Second World War when the British Volunteers for Finland, to which he belonged, was disbanded; and that he had shown in France when he was dropped there by parachute to fight with with the Maquis and liberation forces, and later when he hid for weeks in the Burma jungle with a badly broken foot following another parachute jump. One of Guthrie’s earliest innovative fund-raising efforts was to introduce the popular Christmas Seals – adhesive seal stamps – by having a real seal (which refused to go in the lift) flobber up the stairs at the Waldorf Hotel. (He was discouraged from inviting the Lord Privy Seal to the reception.) In the organisation of the NFPR, which became known to many as the ‘National Fund’ or the ‘Fund’, he was subtle in using the power and the influence of the grandees on the Council but at the same time he had an advisory body of carefully selected experts who advised on the distribution of the funds which were collected. In the early days the fund supported the first European trials of oral poliovirus vaccines in Belfast which established their effectiveness and safety standards for their subsequent world use.

Following this, the fund supported many other aspects of medical research in relation to problems of disablement and funded the endowment of 13 medical chairs in universities in the United Kingdom. Guthrie was given an honorary doctorate and masters degrees from several universities, but he sought no recognition for the greatest contribution any individual has made to funding medical research in the United Kingdom. After polio could be beaten, he changed the name of the fund to Action Research for the Crippled Child, which continued to support a wide programme of research in disabling diseases. Guthrie then turned his attention to the relief and rehabilitation of the paralysed, not only in the UK but in the developing world, and set up ‘intermediate technology techniques’ for developing equipment for the locomotion of the disabled in developing countries. When he retired as Director of Action Research he initiated a programme at the Institute of Child Health to provide essential health education for rural populations in Third World countries, particularly in Africa. This was called ‘Child to Child’ and was largely based on the novel idea of older children teaching their siblings about disease prevention and other health problems. With Alf Morris, he was closely involved in the All Party Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act (1970), which paved the way for subsequent legislation for the disabled in the UK. He was awarded the OBE in 1976.

Guthrie died at Amberley, West Sussex on 12 October 1994. He was survived by his wife, one son and two daughters. He was the driving force behind introducing polio vaccinations into the UK.

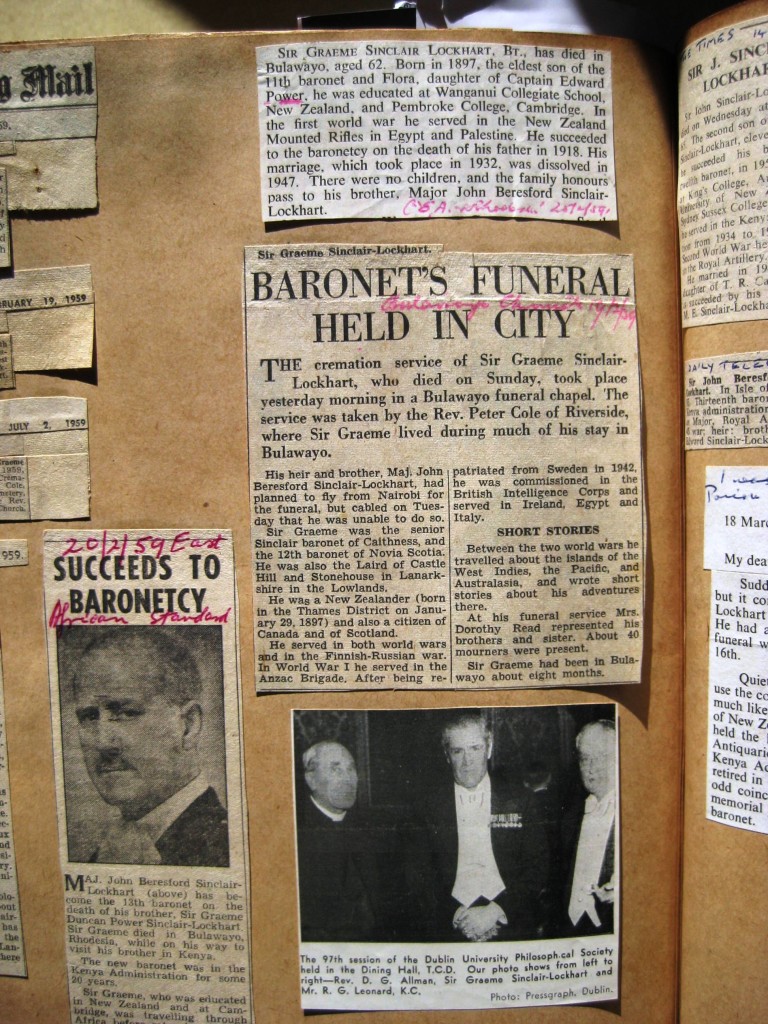

Lieutenant Sir Graeme Duncan Power Sinclair-Lockhart, Platoon Commander, “D” Company

Lieutenant Sir Graeme Duncan Power Sinclair-Lockhart, 12th Baronet from a Photo by Bassano, whole-plate glass negative, 16 June 1920 (National Portrait Gallery, London. Given by Bassano and Vandyk Studios, 1974.

Sir Graeme Duncan Power Sinclair-Lockhart (b. 29 Jan 1897 in New Zealand – deceased 15 Feb 1959) was the 12th Baronet of Stevenson (County Haddington, Nova Scotia, Canada), a title that dates back to 18 June 1636and was awarded by King James I of England. Sir Graeme was the son of Sir Robert Duncan Sinclair-Lockhart (b.1859-d.1918), the 11th Baronet and Flora Louisa Jane Beresford Power. Sir Graeme was educated at Wanganui Collegiate New Zealand (1911-1915) and was working on a sheep station on the East Coast of New Zealand on the outbreak of WW1. He enlisted in 1916 in the New Zealand Mounted Rifles as a Trooper #31096. His occupation is listed as Shepherd and he embarked from New Zealand on 5 December 1916 as part of the 20th Reinforcements (First Section), NZMR, leaving Wellington on HMNZT70, the “Waihora” for Suez and joining up with the 11th Squadron of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles. He was invalided after the Gaza Battle and an article about him mentions “he again associated himself with station interests” – one surmises that this was in New Zealand.

Sir Graeme’s father, Sir Robert Duncan Sinclair-Lockhart, the 11th Baronet and who was associated with the banking business in New Zealand, died suddenly in 1918 during the time of the influenza outbreak. His obituary from 14 November 1918 states “Died suddenly at his residence, Upland Rd, Remuera, yesterday. Sir Robert, who was 58 years of age, was a son of the late Mr George Duncan Lockhart and on the death of his uncle in 1904 he succeeded to the baronetcy. His estate is at Castle Hill, Lanark, Scotland. He also held the baronetcy of Sinclair of Stevenson. In 1895 he married a daughter of Captain Edward POWER. There is one daughter and five sons, of whom Mr Graeme D P LOCKHART, who recently returned from active service, is heir to the title. At one time Sir Robert was a member of the auctioneering firm of Wakelin and Crane, Whangarei, from which he retired on assuming the title. The deceased was greatly interested in all forms of sport and was a keen yachtsman and polo player. As a member of the Pakuranga Hunt Club he was a regular follower of the hounds. He was a steward of the Auckland Racing Club and also a member of the committee of the Auckland A & P Society. He is survived by Lady Lockhart and their family.