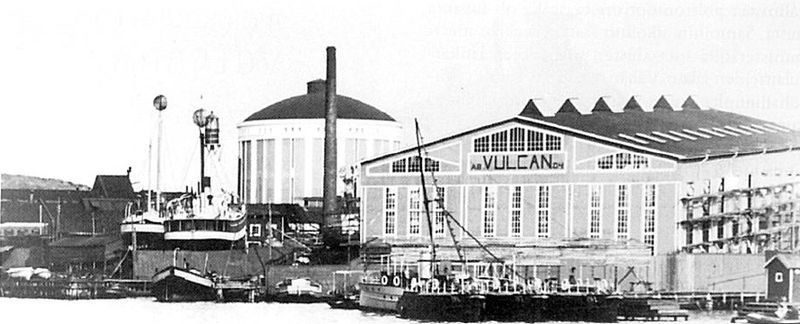

Working behind the scenes, Mannerheim slowly built a coalition of support for his well-thought out proposals for what would slowly evolve into a Finnish military-industrial complex. Essentially, these were broken down into two broad areas. The first was specifically maritime. Bringing together Naval, Naval League, Shipping and Forestry interests, Mannerheim built a consensus that supported a “Naval and Merchant Shipping Act.” The Merchant Shipping component of the Act sought to establish a maritime infrastructure capable of making Finnish maritime trade a year-round affair and establishing state-owned companies capable of conducting Finnish trade with Finnish flagged ships to North and South America and elsewhere. The Naval component of this Act sought to provide a naval force capable of fulfilling the defense role envisaged: securing the demilitarized Åland Islands in the event of war, strengthening the Coastal Artillery to resist landing attempts and securing Finnish trade routes to Sweden and through the Baltic.

The Act initially sought the construction of Icebreakers, to operate under the existing Finnish Maritime Administration, while a new company, Merivienti Oy, was to be established as the state owned shipping company. The two existing Finnish steamship companies were to be allowed a large share in Merivienti Oy, which was also not to be allowed to compete with existing companies in the lucrative European trade. In order to ensure a steady flow of orders for the Finnish shipbuilding industry, the basic schedule to be followed was to first build the Icebreakers necessary for ensuring year-round foreign trade, then build merchant ships to gain experience in building larger and more modern ships, whilst also embarking on a parallel program of continued naval construction on a limited scale.

The second area where Mannerheim successfully generated a consensus of support was in the further development of Finnish Industry. This was broken down into a number of areas: – support for the existing but limited Finnish metallurgical industry, the development of new manufacturing companies specializing in motor vehicles, aircraft and engines for both, the establishment of an oil refinery and oil and fuel storage facilities, and the rapid expansion of Finland’s hydroelectric power production capabilities in order to supply electricity for these new industries and somewhat incidentally (except to Mannerheim) the development of a small internal armaments industry

After the initial groundwork had been laid, the necessary legislation was pushed through the Finnish legislature in 1926 with surprising ease. The Right-wing Kokoomus (National Coalition) Party was dead-set against socialism – but in Finnish political tradition state funding for business has never been seen as Socialism. Their support was unanimous for the legislation put forward. The left-wing SDP (Social Democratic Party) was opposed to the military components but supported the civilian components (and then the legislation in its entirety) due to the promise of more work for industrial workers. The Swedish People’s Party (RKP) traditionally supported the interests of the merchant marine due to the interests of their supporters. The Agrarian Party was staunchly opposed to increases in the State Budget but was supportive of the expansion of the forestry industry (and the possible improved wood prices, important for small and large landowners alike) as well as the improvements in national defense.

The only party wholly in opposition to the arrangement was the Socialist Party of Workers and Smallholders (STP), a cover organization for Soviet-backed communists. Any increase in national defence capabilities was against Soviet interests as were improvements in Finnish industry – particularly as the Soviet Union was heavily dependant on the export of forestry products produced with slave labour in order to acquire much needed hard currency. The STP was a distinct minority, however, and all legislation was passed by the Finnish Parliament in April 1927, to be enacted from 1928 onwards. In practice numerous studies and planning exercises had been completed by the Finnish Navy, Finnish Maritime Adminstration, Finnish Army and Air Force and and Finnish industry associations over the preceding two years of negotiations and consensus building and orders were placed and work commenced almost immediately after legislation was passed.

Development of the Finnish Oil Refinery

The first new project to get underway was the construction of an Oil Refinery. In 1925, Finland had no oil refinery. The country was one of the few in Europe that imported all its oil and petroleum products from abroad and there had been no private industry interest in undertaking refining and bulk storage of petroleum products. Given the increasing strategic importance of oil and petroleum, as well as the Governments plans to boost motor vehicle manufacturing, the legislation specified that the Ministry of Trade and Industry was to establish a company which would construct an oil refinery with the capability for 700,000 tons crude oil capacity and that storage distribution of fuel and lubricant oils were to be placed under the control the same company.

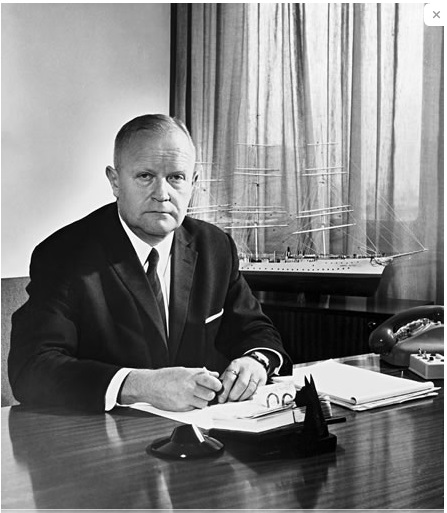

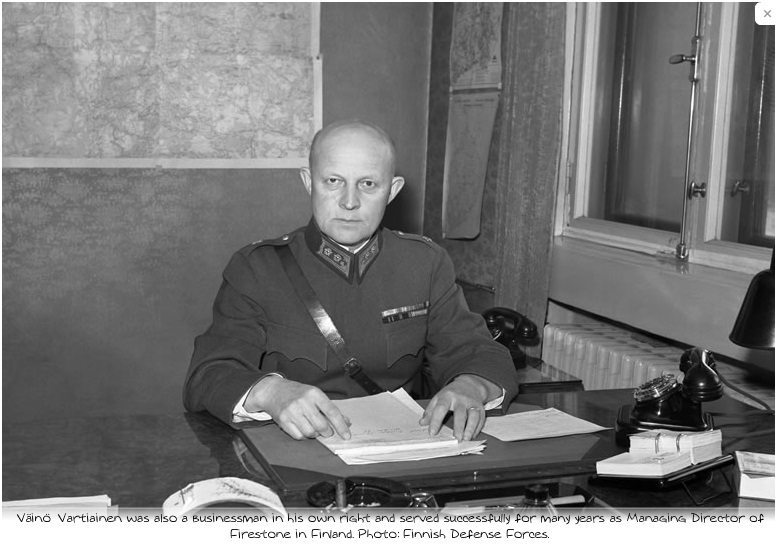

Colonel Vaino Vartiainen was also a businessman in his own right and served for many years as Managing Director of Firestone in Finland

The new agency was to be headed Colonel Väinö Vartiainen, then head of the Finnish Armed Forces Fuel and Lubricants Department, which was responsible for securing Finland’s supplies of Petroleum and petroleum products in the event of a war. Vartiainen was one of the drivers behind the setting up of Neste and served for many years as Chairman of the company’s Executive Board.

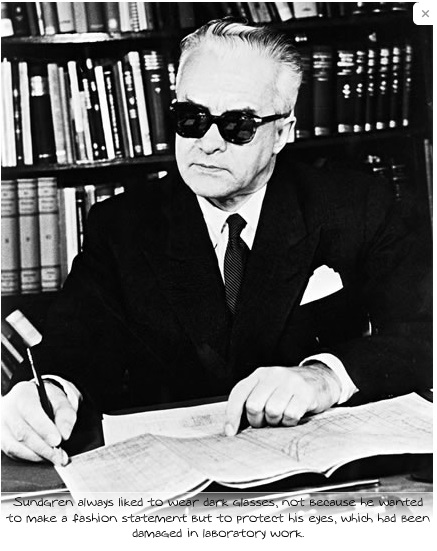

Dr. Albert Ferdinand Sundgren, Finland’s only petrochemicals expert, was a senior staff member of (Sundgren had been a strong advocate of the establishment of an oil refinery in Finland from the start). Sundgren had been born in Russia in 1903, graduated from the Institute of Chemistry in Brussels in 1924 with a Degree in Chemical Engineering and from the University of Strasbourg in 1926 with a Masters Degree in Engineering.

Four years later (in 1930), he was awarded a Doctorate by the University of Strasbourg. While studying for his Doctorate, he had returned to Finland and presented the idea of a Finnish oil refinery to senior figures at the Bank of Finland and the Armed Forces. His proposals had won the support of Marshal Mannerheim, who brought them to the attention of influential Finnish industrialists and politicians.

Sundgren was the only Finnish specialist at the time who had concrete experience in the international oil industry, and despite his youth, he had the experience and knowledge to make it a reality. He was also fluent in a number of languages, which would prove invaluable. Together with Vartiainen, Sundgren can be considered one of the two central figures who were the guiding influences behind the birth of the Finnish Oil Industry and of Neste. Sundgren always liked to wear dark glasses, not because he wanted to make a fashion statement, but to protect his eyes, which had been damaged in laboratory work.

Finland had up until this point relied on the major Oil Companies for its fuel supplies. There companies were large and influential and attempted to influence the decision by making the refinery plans look unfavorable.

However, concerns for this strategic chokepoint won the day and late in 1926 the decision to set up Neste Oy (Finnish=”Liquid”) was made, with its first general meeting held on January 2, 1927. The state of Finland was registered as a shareholder with 207 shares, Oy Alkoholiliike Ab, the state-owned alcohol monopoly with 140 shares, Imatran Voima, the recently established state-owned power company, with three shares and the Ministry of Defence with 50 shares.

Eino Erho was appointed Neste’s first CEO at the first general meeting, a position he would hold until 1955, when he was succeeded by Uolevi Raade. In the articles of association of the company, it was stated that its purpose was to refine oil, own and rent storage for liquid fuels and lubricants, and to act as importer, refiner, transporter, and manufacturer of these products, as well as trading in them.

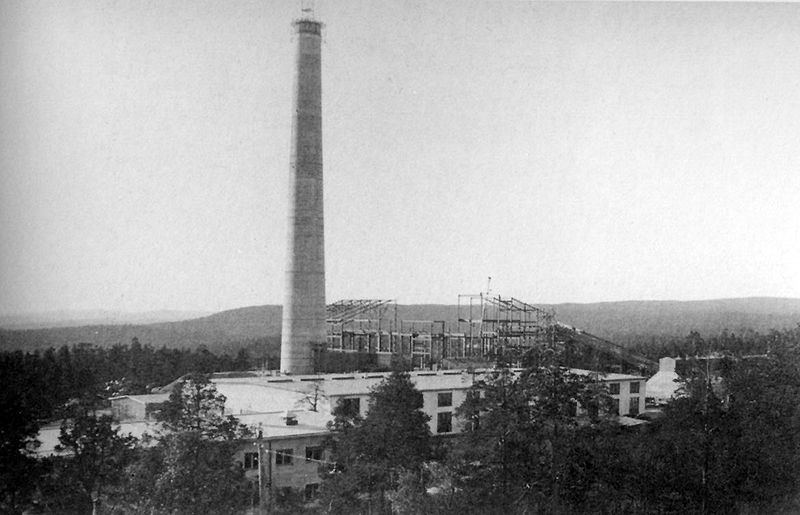

Neste planned to store its fuel oil and lubricant supplies in caves in the granite rocks of Tupavuori, in the township of Naantali on Finland’s southwestern coast. The storage caves in Naantali were named NKV, from the Finnish words for Naantali Central Storage. An area near the cave storage reservoirs was selected as the future site of the refinery. The harbor conditions at Tupavuori were considered to be excellent. The planning of the refinery was entrusted to a U.S. firm The Lummus Company, an early specialist in the field. The delivery of plant and equipment was entrusted jointly to the French company Compagnie de Five-Lille and Germany’s Mannesmann. The civil engineering was carried out by Neste itself. Construction work started at Tupavuori in Naantali in October 1929, and the inauguration of the refinery was held on June 5, 1932.

The start-up of production in August 1934 had already shown that no technical problems existed. The guaranteed capacity of 700,000 tons was reached by the beginning of October, and soon it was apparent that the new refinery could reach a capacity of up to 1.2 million tons of crude oil per year. Neste had planned to refine crude oil from many sources, primarily from Western suppliers. As the company had no intention of forming a retail delivery system of its own, the marketing of products was based on cooperation with oil companies already operating in Finland. The most important of these were Shell, Esso, and Gulf. Shell and Gulf delivered crude oil of their own to be refined by Neste. All prices were tied to international market rates.

However, the Government saw an opportunity to expand trade links, which were almost non-existent, with the Soviet Union and in 1935 a trade agreement was signed whereby Finland obtained half the needed supply of Crude Oil from the USSR in return for the supply of heavy industrial items including merchant shipping and locomotives (this reciprocal trade with the Soviet Union is an area that will be addressed in more detailed later). Neste’s strategy was to deliver all the motor petrol Finland needed and adjust the production of other derivatives of crude oil accordingly. Thus the company chose a technology that gave maximum petrol output. At the same time, the sourcing of crude oil from the Soviet Union led to an increase in Finnish exports in payments, as Finland preferred not to use their somewhat limited foreign currency where not necessary.

This led to increased exports, in particular for the Finnish manufacturing industry. In 1937, Neste purchased Sköldvik Manor, an area of 628 hectares near the town of Porvoo (east of Helsinki) with good access to deep water, as the site for the development of a heavy chemical industrial complex. The plans received favorable publicity. Finland was living in a climate of industrial growth and was optimistic about the future expansion of technology. Neste started detailed planning for this event, with Erho announcing that construction would begin in 1940. Constructions Plans were drawn up, again with Lummus, but these plans had not been completed by the outbreak of the Winter War. In the event, construction would start shortly after the end of the Winter War, with detailed plans completed by 1941. Erho announced that Neste would be in a position to enter the petrochemicals sector by 1951 but as it happened, the German attack on the Soviet Union intervened and work would in fact not begin until the 1960’s.

The company acquired its first tanker, the ST Neste – built in 1921 and previously known as the Torborg -in 1930.

In conjunction with other legislation being passed, it had been decided that Neste would import crude oil primarily in ships owned by the company. In the spring of 1930, Neste purchased an old oil tanker (the Torberg, renamed ST Neste) from Norway in order to gain experience with the shipping of oil products. At the same time, anticipating completion of the refinery in 1935, initial orders were placed with the Finnish shipbuilding industry for the construction of six crude oil tankers (named the TT Jurmo, TT Jaarli, TT Jatuli, TT Uikku, TT Ternholn and TT Kiisla).

Soviet oil was imported from Black Sea ports, while crude oil was also imported from Persia. By the late 1930’s, Neste had 18 tankers (six modern tankers built in Finland and ten older tankers purchased second-hand from Norway, the US and Britain) plus five tugs and carried much of the Oil imported into Sweden and the Baltic States as well as for Finland. Anticipating the outbreak of WW2, Neste had by 1939 built up large stockpiles of both crude oil and refined petroleum products in the storage cave reservoirs near Naantali, estimated to be enough to supply the entire country for six months. With strict rationing, these reserves proved to be sufficient for the duration of the Winter War of 1939-40.

Development of the Finnish Power Generation Industry

When Finland gained independence in 1917, despite being a leading timber exporter, much of the timber felled annually from its forests was used as firewood – annual fellings from its forests amounted to nearly 30 million cubic metres, of this over 20 million cubic metres was used as firewood. The firewood was sold as metre-long split billets, and neat stacks of them could still be seen throughout Finnish countryside and towns in the 1960s.

Firewood for Helsinki was stored on Hakaniementori square during both world wars.

Source: Helsinki City Museum

Besides being used for heating buildings, wood was also used to fuel steam engines and boats. Despite this heavy reliance on wood for heating and energy, Finland was at the forefront of European electrification. The initial stage of the history of electricity dates back to the turn of the year 1877-78, when Finland carried out its first experiments with electric light. The first permanent power plant producing electric light, which was also one of the first in Europe, was erected at the Finlayson factory in Tampere in the spring of 1882. Within a year, electric light was coming on in Pori, Jyväskylä and Oulu. Helsinki received its first power plant in 1884, the same year as Berlin.

The first pioneers of Finnish electrification built power plants, acted as importers of electrical goods, and even manufactured the equipment and appliances needed to produce electric light. At first, all electrical goods were imported from abroad. In 1889, Gottfrid Strömberg set up a company in Helsinki bearing his own name, and this company became the mainstay of the Finnish electrical industry for almost the next one hundred years. At the turn of the last century, some small-scale hydroelectric power stations and other kinds of power plants were built in Finland, and these brought electrical power to factories and light to urban dwellings.

The First World War and the Civil War slowed the pace of Finland’s electrification, but after the war, a large number of electrical companies were established in Finland, and new factories were built, such as Suomen Kaapelitehdas (the Finnish Cable Factory), later to be called Nokia Cable, a forerunner to today’s Nokia. Old German companies also returned to the Finnish market, and a group of new companies was set up, including Osram of Germany, Philips of the Netherlands and L M Ericsson of Sweden. In the 1920’s, much national effort went into the construction of the power station at Imatra and the erection of a power line from Imatra all the way to Turku. Construction at Imatra started in 1922 and the power plant, the largest hydroelectric plant in Europe, was completed and electricity production started in 1929.

In addition to Imatra, in order to support the planned development of large scale heavy industry in the region, the building of a number of hydro-electric power plants in the Oulujoki and Kemijoki river catchment areas was planned, with work commencing immediately on completion of Imatra (this was largely done in OTL during the post-war decade using pre-war plans). The hydropower plants in these two rivers were intended to not only supply local industries but also to transfer power to more populous and industrial Southern Finland. While these plants were smaller than Imatra, they were more numerous, and with construction work on the first starting in 1928, these began generating ever increasing amounts of electrical power from 1931 on, with construction continuing unabated up until the outbreak of the Winter War in late 1939.

The Development of the Finnish Mining Industry

The nickel mine at Petsamo in the far north of Finland has already been noted in passing. Given the growing importance of mining to the Finnish economy through the entire decade of the 1930’s, the entire mining sector is worthy of further examination, following which we will in the next section look at other areas of the economy that grw together with the financial and social ramifications of the rapid growth and industrialization of Finland’s economy – particularly on state income from taxation and from state-owned companies – and the flow-on effects for the defence budget.

Nickel was an important strategic resource, potentially of great importance for production of munitions, tanks and other war-related materiel as it was used to make alloys of steel (particularly stainless steel) important for improved corrosion resistance (shipbuilding) and outstanding high temperature performance (aircraft engines), armor plate and ammunition. The first Finnish nickel deposits were found in the Petsamo area on the Barents Sea, the northernmost part of Finland in the early 1920’s and were Europe’s richest nickel deposits. Finland had gained control of Petsamo in the Tartu Peace Agreement reached with the USSR in 1920. An early assessment of the region’s natural resources revealed that the forest and mineral exploitation would be expensive and risky, and unlikely to attract sufficient capital. An early proposal for a rail link to Rovaniemi was rejected by the Government.

The Government conducted a geological survey of the area in 1921. On the Norwegian side of the border an iron ore field had already been found, and it was hoped that the ore would continue on the Finnish side. In the summer of 1921 the survey identified Neck Kolosjoelta Fell, near the Norwegian border and about 40 miles from the coastm as a nickel-copper ore deposit. In 1922, the Finnish Geological Commission mapped out the preliminary size of the orebodies and explained the content of the ore. The ore was calculated at about two million tons, and was estimated to contain 1.3 per cent nickel and 1.6 percent copper. A preliminary assessment determined that while the result was modest, the ore might still be enough to start mining. The calculated concentrations later proved to be significantly below those of the actual nickel content, which proved to be 3.9 percent over a thirty kilometer trendline.

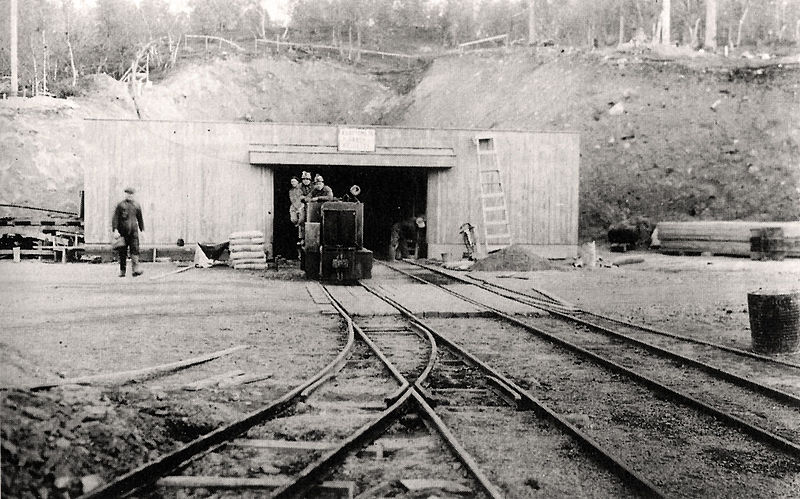

The deposit was first offered to a Finnish state-owned mining company, Outokumpu Oy, but Outokumpu was already heavily committed and had insufficient resources for two projects. Early interest was shown by several international mining companies, including German companies Krupp and IG Farben and the Canadian International Nickel Company of Canada (Inco), which controlled 90 percent of world nickel market and owned most of the world’s known nickel resources. Demand for nickel on the world market was growing rapidly during the 1930s due to the use of steel/nickel alloys, used to improve the strength of the steel as well as humidity and temperature stability characteristics. Negotiations with Inco were long and thorough, but the agreement was approved in June 1932 At this stage, the ore was estimated at double the original calculation. The contracting parties were the State of Finland and the UK registered subsidiary of Inco, Mond Nickel Company . Mond held the right to the Kolosjoen orebodies for a fifty year period. Work began in 1933 to build a mine to Canadian plans. A three mile long underground tunnel was built, with work going on in 3 shifts.

Initially, the ore was shipped to the United States from the small Finnish Barents Sea port of Liinahamari (which was ice-free all year round) for smelting, but when it became clear that electric power would be available, Inco decided to build a smelter in Petsamo, where ore was processed to semi-finished 50% nickel (matte). The high brick chimney of the smelter, when completed, was the highest in Europe at 163 meters (the Masons were Americans). By 1936 the mine, powerplant and smelter were fully operational and producing approximately 3,000 tonnes of pure nickel annually (although it was processed and shipped as matte – the refined so called “Matte” contained about 50% of nickel. There were usually other metals with nickel, particularly copper, gold and silver). The mine employed about 1,400 employees.

When development started, the area was untouched wilderness. To accommodate the employees, an entire town was planned, with roads, utilities, a market, cinema, tennis courts, workshops and administration buildings. The town was designed by architects Kaj Englund and Olav Hammarstrom and was completed over a two year period from1934-35 with 140 homes. The buildings were modern, with central heating, bathrooms and modern kitchens. Building material used were new porous concrete hole bricks. The site of the town was also connected by road to the south in 1931 (construction of the road from Sodankylä through Ivalo to Liinahamari started in 1916 and was completed in 1931. After that Petsamo became a popular tourist attraction as it was the only port at the Barents Sea that could be reached by an automobile).

At this stage Finland was also of increasing interest to Germany, who saw Finland’s nickel deposits as a vital war industry in any major conflict. In 1937 the Germans expressed an interest in purchasing nickel from Petsamo. This was of concern to the British Government, who were again concerned when they found, in September 1938, that the the German General Staff’s Economic Representative had traveled to Finland to investigate materials available for use in the production of munitions and had expressed the wish that Finland would sell all Nickel production to Germany (at this stage, Nickel was a major source of concern to Germany –their nickel self-sufficiency was only 5 per cent). At the same time, Finland was also seeking to raise revenue to finance further defence spending and pressured Inco to increase production at the Petsamo facility. Smelter capacity was expanded, port capacity Liinahamari was increased and, with open-cast mining introduced, by 1939 production had expanded to 220 000 tons of ore, (8,000 tonnes of pure nickel). Of this, more than than half of ore was smelted into matte on site, while the remainder was shipped out as ore to Britain and the United States. This was a valuable source of foreign exchange for Finland and, increasingly, was carried on Finnish-built and owned merchant shipping.

However, while the nickel deposits at Petsamo were important, there were two other nickel mines in Finland that had entered operations in the mid to late 1930’s, one of which, the Kotalahti mine, was almost as significant as the Petsamo deposit. The Kotalahti mine in Leppävirta was mined from 1934 to 1967 and the Makola Mine, near Nivala, entered production in 1937. The Makola Mine yielded around 500 tonnes of Nickel annually, the Kotalahti Mine was producing 424,000 tonnes of ore annually by 1939, yielding 2,800 tonnes of pure Nickel. Both of these deposits were mined by the state-owned mining company, Outokumpu and a political decision was made to sell a good part of this production to Germany. Accordingly, in early 1937 the Government signed a contract for the supply of 3,000 tonnes of Nickel annually, sourced from the Kotalahti and Makola Mines and generating substantial revenue for the Government (and for Outokumpu).

Outokumpu Oy itself had, by the late 1930’s, become a significant player within Finland’s economy. Outokumpu was a mining and metallurgical company, headquartered in Espoo and managed by Eero Makinen. The company took its name from the town in the eastern part of Finland where a rich copper ore deposit was discovered in March 1910. The deposits owners, both the Finnish State and private players, could not agree on a clear direction for the project and WW1 then intervened, with financial difficultiues and limited capital hindering the launch of efficient production. From 1913, copper ore was smelted and refined in a small copper works next to the mine. While the process was inconsistent, sufficient raw copper was produced to meet domestic demand together with some exports.

Things began to take off in 1924 when the State became the sole owner of the deposit and then when, as part of the Industrialisation Legislation of 1926-27, the deposit was transferred to the ownership of a state-owned mining company, with Eero Makinen appointed as manager. The old copper works was closed in 1929 as Ourokumpu began drafting plans for an integrated copper chain. The first step in Outokumpu’s integrated copper chain was completed in 1931 when an electric smelting plant, the largest of its kind in the world at that time, was built in Imatra to take advantage of the power from the newly completed Imatra Dam. The next step was the building of a metal works in Pori, where the raw copper produced in Imatra was refined into semi-finished prodicts such as wire ingots, sheets and rods (Outokumpu’s “concentrated copper ore” contained 4% copper, 28% iron, 25% sulphur, 1% zink, 0,20% cobolt and additionally 0.80 grams of gold and 9 grams of silver per ton of ore).

The opening of new nickel, zinc and copper mines in Finland in the 1930’s enabled Outokumpou to develop into a multi-metal company, with a new nickel works built at Harjavalta in 1934 and zinc and cobalt works in Kokkola in 1936. Outokumpu was also the owner of the newly constructed Tornio Steel Works, in the small town Tornio on the coast of Gulf of Bothnia, with up to 85 pct of the product exported. In the late 1930’s, Outokumpu also opened another major Copper mine at Ylöjärvi, near Tampere. Outokumpu also started down the road to stainless steel in 1937, when it began to exploit a large chrome ore deposit in Kemi. The construction of a ferrochrome smelter in Tornio (a joint venture with the Swedish firm Avesta), combined with the nickel works in Harjavalta, provided Outokumpu with the key raw materials for stainless steel, and the production of this was a natural next step, with 10,000 tonnes annually being produced by late 1939. The company’s net sales increased tenfold between 1930 and 1939, by which time Outokumpu was Finland’s third largest export company.

As the pressure from the USSR grew ever more pressing in the late 1930’s, Finland began to use it’s position as a key supplier of Nickel to Germany and an important supplier to the UK as leverage in negotiations for the purchase of weapons, munitions and technology. In the case of Germany, this resulted in Germany supplying Finland in early 1939 with some two hundred 88mm Anti-Aircraft guns together with ammunition, designs and a manufacturing license as well as shiploads of coal (as Finland began to build up strategic reserves of coal and oil). The 88mm guns were pressed into service as Anti-Tank Guns in the Winter War, first used in the Battle of the Summa Gap with devastating effect on Russian armor. In the case of the UK, Finland was able to exert less pressure (the Inco Mine in Sudbury, Canada, supplied the bulk of the Nickel needed for the USA and the UK) but was able to pressure the UK into selling aircraft, including a limited number of Hurricane Fighters, as well as the transfer of technology. This included aircraft engine designs, export licenses for the De Havilland Wihuri and Miles M.20 Fighter, as well as designs for both, all of which would be invaluable to Finland in the Winter War.

At the same time, increasing amounts of metallurgical products from Outukumpu and other Finnish companies were going into the expanding Finnish Maritime Construction Industrial Complex. Both merchant ships and warships demand large quantites of steel, and between the demands of the new Finnish shipping lines, the ongoing Finnish Naval construction program, sales of merchant ships to the Soviet Union and the building of both Baltic and transoceanic ore carriers and Oil Tankers, the Finnish Maritime Industrial Complex was expanding rapidly. There were other internal demands – for the burgeoning automobile industry as well as for the internal Armaments Industry that had been slowly developing through the 1930’s to meet Finland’s defense needs.

But besides the keystones of the Finnish economy of the 1930’s – Lumber, Pulp and Paper, Metallurgical and the heavy industrial companies (the Maritime Complex, Sisu, Neste and othere) – there were other Companies within Finland that were beginning to emerge, less significant in terms of pure percentages, but significant in terms of technology and knowledge.

Development of the Finnish Motor Vehicle Industry

Prior to 1928, all motor vehicles used in Finland had been imported built-up from abroad. As part of the industrialisation program the Finnish Government established “Sisu Auto Oy” in 1928, with a truck and bus factory constructed Hämeenlinna, some 100 kilometres north of Helsinki. The first nine Sisu vehicles, a prototype series consisting of a bus and eight trucks, rolled off the production line in 1929. With the large and growing demand for heavy vehicles for both the forestry industry and for construction work, production was expanded until by 1935 some 1000 trucks and 200 buses (some being exported) were being produced annually. A third production line was added in 1932 to produce tractors for agricultural use. These were, incidentally, designed so that, in the event of war, they could be used to tow artillery. Construction was expanded further in 1938, with a fourth production line introduced and the work force being expanded to produce trucks for the military.

Sisu’s primary competition for the Finnish vehicle market came from the Ford Motor Vehicle Company of Finland, Oy Ford Ab. The Nyberg brothers from Nedevetil had been the first Ford Dealers in Finland, returning from America to open business in 1912. When Ford started production of his Model T, the three brothers Alexander, Fritjof and Tor Nyberg from Nedervetil were emigrants in Arizona. With their business sense they realized that the Model T Ford was something in which to invest. What followed was the introduction of the Ford automobile to Finland when the brothers imported the first Ford and built up a sales system. They went to the Ford sales office in New York and negotiated to establish a sales network in Finland which was still a part of Russia at that time. While Ford was producing and setting up sales of his automobile, he received assistance from pioneers in other countries. He revolutionized the way of life with the combustion engine’s triumphal march around the world. On the basis of the experience of the first five years, by 1908 he began production of the world famous Model T which brought a world-wide demand for the Ford cars.

While Henry Ford was building his own enterprise without foreign financing, Ford’s first representatives were mostly “self-made men” — businessmen without other capital but with a lot of energy. Their first operation became a great adventure for them with shining results which they had never

. The three brothers from Gamlakarleby were pioneers and adventurers whose foresight we can thank for the coming of age for Ford in Finland. They were happy to receive an affirmative reply from Ford’s New York office as to whether there was an opening for a Ford representative in Finland. During the hectic production schedule no one had time to give a thought to remote Finland as a place for a Ford sales office. After the Nyberg brothers received approval to their proposal they were urged to contact Ford’s chief agent for Europe who had his office in Paris. Light-heartedly Fritjof and Tor rushed back to Finland, while their oldest brother Alexander went to Paris. He used the “captain’s title” he had received as a mining foreman in America and reported to the European director, H. B. White. White, who had a hundred irons in the fire, tersely announced that he could give the Finlander only two minutes of his time. But Alexander, slow and thorough by nature, took his time and explained his proposition. When White heard what Alexander said he became interested and asked all about Finland and the two minutes stretched into two hours. Alexander left the office with an agreement in his pocket.

The brothers first had to take a test for a professional driver’s license. Their instructor was the known motor vehicle inspector and engineer Thornwald Tawast. Then they set up a sales office at Norra Magasingatan 6 and immediately began to cultivate business from their countrymen. The first Ford was expected to arrive in the country during late winter of 1912. Drivers were in the minority at this time. Consul Nikolajeff had begun to import automobiles to Finland in 1905, but no one would have dreamed the effect the Ford Model T would have when it came to the country. Automobiles were still a rarity on the roads and were considered a luxury item reserved for the rich. Three roads reached Helsingfors by 1912 which gave the brothers an opportunity to tour in their own auto around Finland. The first Model T was equipped with a brass hood, carbide lamps and a cloth top. For their first car the brothers had to pay a total of 2500 marks, including freight and customs. The Ford factory established a retail price of 4400 marks. The first test drive only went to Uleåborg and the car generated great excitement everywhere. For the first time people saw a vehicle that drove without a horse and they foresaw that wild reckless driving would lead to the speedy destruction of the world. Gallen-Kallela, who made the first auto posters was at the steering wheel. Despite old women rolling their eyes, the first Ford was a huge public success. People gathered to see with their own eyes a vehicle that went with its own power, and it was impossible to arrange for test drives for all who wanted to ride. Orders came thick and fast for the brothers who already received a hundred names during the first demonstration drive.

The T-Ford is making its entry into the countryside of Ostrobothnia near Sideby in 1927. Erik Storteir, 17 years of age, is sitting on the hood of his first T-Ford. Passengers were Dagny Lassfolk, Gerda Söderlund, Ingrid Hällback, Elin Lassfolk and Valter Norrback

Between 1910 and the 1920’s, Ford had various dealers within Finland, in 1925 selling 3,661 vehicles (more than half the cars sold in Finland at that time were Fords). In 1926, Ford established the Ford Motor Company of Finland. By 1929, the company’s shares made up 40% of the domestic share market. In 1938 the company was listed on the Helsinki Stock Exchange, listed as Oy Ford Ab. While for Ford, the 1920s ended in the stock market crash of 1929 and economic stagnation, in Finland, due to the Governments economic policies and industralisation programs, business grew.

In 1930, with government encouragement and financial incentives, construction work started on the Helsinki Hernesaari assembly line, which was completed in 1931 (together with a domestic engine plant which was later expanded to produce engines for Finnish-manufactured tanks and armored fighting vehicles), with the first domestic Ford vehicles being delivered off the construction line in early 1932. The initial assembly line produced cars (the Ford Model-A) and light trucks and sales were steady through until 1935, after which sales began a steady increase as economic conditions began to improve. Light Trucks found popularity largely in rural districts and were increasingly used by farmers and small rural businesses. Produced in a Panel Van version, they were also used increasingly within the cities and larger towns by organisations such as the Finnish Post Office. Sisu and Ford did not compete directly with each other – Ford produced no real competitors for the now established Sisu line of heavy vehicles and Sisi did not produce cars or light trucks. Import taxes restricted the importing of vehicles into Finland to a small number of luxury vehicles. Interestingly, a number of American engineers and skilled auto workers had moved to Finland to assist in establishing the Plant and its production lines, a number stayed on in Finland after initial work had been completed and many of these continued through the Second World War.

By 1935, the Finnish motor vehicle industry was producing approximately 1,000 Sisu heavy trucks and around 10,000 Ford cars and light trucks annually, with all the components being manufactured within Finland. This had ramifications beyond the mere construction of motor vehicles – and a good example of some of the other ramifications of the rapid development of the Finnish motor vehicle industry can be seen by looking at the history of Imatra Steel Oy Ab. The origins of the Imatra Steel group could be traced back to the early years of the Finnish and Swedish iron and steel industries. The core of Imatra Steel stemmed from 1630, with the founding of the Antskog ironworks, one of the earliest in the Swedish kingdom, which included present-day Finland among its territorial holdings at the time. In the 1640s, the owner of the Antskog works expanded, founding a new ironworks in the town of Fiskars.

When the ironworks were founded in Fiskars, Finland was under Swedish rule, and Sweden was one of Europe’s biggest producers of iron in the seventeenth century. By 1647, the Fiskars works had come into the possession of Peter Thorwöste, originally from Holland, and in 1649, Thorwöste was granted the privilege of setting up a blast furnace and bar hammer in Fiskars for the manufacture of cast iron and forged products. The iron ore used in Fiskars was mainly brought in from the Utö mine in Stockholm’s outer archipelago and most of the bar iron manufactured at the ironworks was shipped to Sweden to be sold on the Iron Market in Stockholm’s Old Town. In Fiskars, the iron was also used to make nails, thread, knives, hoes, iron wheels and other things. This laid the foundation for the Fiskars company.

Fiskars village as shown in a lithograph by P.A. Kruskopf from 1848 – See more at: http://www.fiskarsgroup.com/about-us/our-heritage#sthash.vnIw6JVw.dpuf

Fiskars was to change ownership a number of times over the following century, and along the way had ceased iron production in favor of copper production. In 1783, the ironworks was taken over by the Björkman family and production focused on processing copper ore from the nearby Orijärvi copper mine. By the nineteenth century there was little copper left to be mined in Orijärvi, so the blast furnace was closed in 1802. Since then there has been no basic iron manufacturing done in Fiskars Village.

Fiskars was to change ownership a number of times over the following century, and along the way had ceased iron production in favor of copper production. In 1822, however, the works was bought by pharmacist Johan Jacob Julin, from Turku, who reoriented the company to focus on manufacturing products from processed iron. In 1832, Fiskars established Finland’s first cutlery mill, producing knives and forks and also the scissors and other utensils for which the company would eventually become known worldwide. Fiskars also became an early player in Finland’s Industrial Revolution, inaugurating its own machine and engineering workshop in 1837. By the following year, the workshop had completed its first steamship engine.

Johan Jacob Julin, was born on August 5, 1787. He always used the name John. He was ennobled in 1849, and his time proved one of the most important stages in the history of the ironworks. Oil painting by J.E. Lindh

The Fiskars tradition of implementing reform and innovation has its roots in this period. Many social reforms also took place during Julin’s ownership, during which the ironworks village got its own school and hospital. Farming in the village was greatly improved. Fiskars had a significant influence on the development of Finnish agriculture, and in its day the Fiskars plough workshop manufactured more than a million ploughs. Under Julin’s leadership, Fiskars became known for its farm and household implements, and the Fiskars name became synonymous with high quality.

On the death of J.J. Julin, the ironworks were lead by a guardianship administration. Little by little the power was amassed by Emil Lindsay von Julin and the limited company Fiskars was founded. In 1915 Fiskars was listed on the Helsinki Stock Exchange.

The development of machinery and equipment, the laying of the Finnish railroad system, as well as the construction of bridges, led Fiskar to continue to expand its production in the middle of the 19th century. In 1890, the company acquired a bankrupt steel mill at Aminnefors, which Fiskars then renovated, installing new furnaces. The productivity of the ironworks was raised by developing improved methods of processing steel and by renewing the rolling mill at Åminnefors. The product range was expanded and Fiskars founded Finland’s first metal spring factory.

The development of the internal combustion engine resulted in the creation of new machinery types and new motorized vehicles; it also led to a need for new types of components, including springs. By the end of World War I, the Aminnefors site had begun producing its own spring-grade steel, leading Fiskars to establish a factory dedicated to the production of springs, particularly for the railroad industry, in 1921.

Fine forgers began their training at an early age. Interior at the Fiskars cutlery mill early 20th century

In the 1920s, Fiskars continued to expand its steel production operations, buying up iron and steel works across Finland, including the Inha Works in Ähtäri, Oy Ferraria Ab and the Billnäs Bruks works, which remained a key part of the group, which renamed itself Imatra Group in 1927. In 1929, the company began manufacturing the first springs for Sisu trucks. With the rapid development of the Finnish motor vehicle construction industry including the Sisu Auto Plant and the new Ford Plant constructed in Helsinki, Imatra Steel found a new, specialised and rapidly expanding market. Motor Transportation was expanding rapidly from the mid 1920’s due to a combination of the expansion of forestry industries and the growth in large scale construction and building projects. Large number of small transport companies operated heavy trucks (for their time) during winter in support of wood procurement and delivery and during summers on various construction projects. At the same time, the general population was benefiting from the growth in the economy and more and more people could afford cars while small businesses were increasingly utilising the small trucks and panel vans produced by Ford. The Finnish motor vehicle construction industry needed parts, and Imatra Steel worked to meet the demand, rapidly becoming THE specialist manufacturer of steel and steel components for the automotive and mechanical engineering industries within Finland.

The company’s products expanded to include low-alloy engineering-grade steel bars, produced at the main Imatra steel works, as well as forged engine blocks and axles, crankshafts and camshafts, leaf springs and stabilizer bars, connecting rods, and components for steering columns for cars and heavy trucks. In addition, with the growth in shipping construction, Imatra Steel also became a supplier of steel and steel components for the shipping industry and also began to develop a sideline in components for the small Finnish aircraft manufacturing industry as well as a wide range of non-automotive steels and steel products including nails, chains, and wire rods. When the government joint venture with Tampella, Patria Oy, began, in the late 1930’s, producing tanks and then other armored fighting vehicles for the Finnish Army, Imatra became a major parts supplier. And Imatra Steel was only a single example. There were many more, both large, medium and small, spread acoss the entire spectrum of the Finnish economy.

The expansion of civilian motor transportation, particularly in heavy trucks, had implications for national defence. In early 1930’s, a divisional organic light artillery regiment used 1164 horses for summer TO&E. Out of the manpower of some 2363 men in the artillery regiment, half were involved in keeping the horses operational. Together with planned and expected reinforcements, an infantry division employed 3200-7000 horses for a total planned wartime horse strength for the Army of 60,000 horses with a daily consumption of some 6000 tons of fodder – a far heavier burden for logistics than for example a daily ration supply for the troops.

As a result of the rapid increase in trucks (Army mobilization plans called for the requisitioning of a large percentage of available heavy transport), in 1939 the new TO&E could replace most of the horses with motor transportation in the Army Field Infantry Divisions destined for the fairly well developed Karelian Isthmus. Troops destined for Northern Finland retained more horse transportation, although in many cases horses were supplemented with agricultural tractors. These changes liberated some 15% of the military from the care and maintenance of horses and allowed the Army to add three more Divisions to the Field Army. An even more important aspect was that as a result of the expansion of logistical assets, the operational mobility of the ground forces was significantly improved and the dependence on the rail network was lessened.

Forestry – a brief introduction

Finland’s economy largely relied on her Forests, with Finnish farmers owning approximately half the forested land, the state owning a third (mostly in the North) and the remainder largely owned by forestry companies. Sawmills and lumbering were a large source of employment in rural Finland, and in the 1930’s Finland led the world in the export of sawn timber, ahead of Canada, the USSR, Sweden and the USA. Britain was the largest buyer, followed by Germany, Holland, Denmark, Belgium and South Africa.

With the rapid acceleration of industralisation and the consequent movement of people from rural areas to the towns and cities, there was a growing demand for housing. This resulted in the emergence of a new industry, which rapidly became one of Finland’s largest – the manufacture of prefabricated houses, schools, stores and warehouses. Initially, these were built for the Finnish market, but it was found that there was also an export market and through the 1930’s, sales picked up rapidly. In 1935 for example, 35,000 prefabricated houses were sold to the USSR. As their economies recovered from the Great Depression, Poland, Denmark, France, the UK, Holland, Belgium and Germany were among the countries which brought large numbers of these houses, with some thirty other countries buying smaller numbers.

Finland had, in addition to forestry, established a large variety of forestry-related industries including mechanical pulp mills, cardboard and building board factories, sulphite and sulphite cellulose mills as well as paper mills. In 1932, Finland’s mechanical pulp production totaled 750,000 tonnes, cellulose 1.5 million tons and paper 550,000 tons and these numbers continued to climb through the 1930’s. The first plywood factory was built in 1912 and by 1938, there were eighteen mills manufacturing plywood and exporting 200,000 cubic meters annually. In 1930, Finland began to manufacture wood-fiber panels and a growing world-wide demand for this product had led, by the late 1930’s, to eight factories having been established to meet demand.

Finland had also established many smaller industries, both before and after independence, many of them to supply her own needs. As we covered earlier, the development of hydroelectric power was important to Finnish industry, as Finland had and has no black coal fields. With the development of hydroelectricity and the provision of increasing amounts of cheap power through the 1920’s and 1930’s, Finland’s small industries were able to increase production and compete successfully in both domestic and foreign markets. We’ve already looked at the metal industry’s growth – by 1938 this sector of the economy employed 83,000 works in 1,000 different companies, building machines and equipment for the woodworking industry, locomotives, ships, electrical machines and equipment, cables and machine tools, fittings for water and steam pipes, separators, and automobile parts, bodies and engines among others.

For a further example, the first porcelain factory in Finland, the Arabia, was started in 1874 in Helsinki, producing a wide variety of porcelain and earthenware articles such as toilets, basins, baths, technical porcelain, china and the like. Arabia’s products won the Grand Prix at the World Exhibition in Barcelona in 1929, Salonika n 1935 and Paris in 1937 and were sold in more than thirty countries. Arabia’s factory was the largest porcelain and china factory in Scandinavia, with 3,000 employees.

Another of Finland’s important secondary industries was clothing and textiles, with factories in Tampere employing around 10,000 people, nearly all women, and satisfying primarily domestic demand. By 1934, Tampere had the largest textile manufacturing plant in Scandinavia.

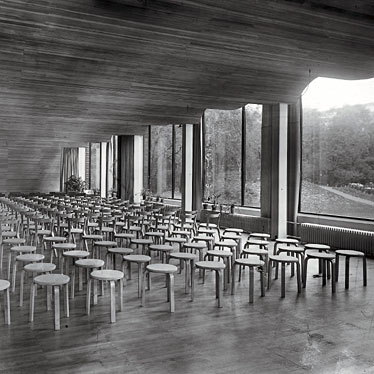

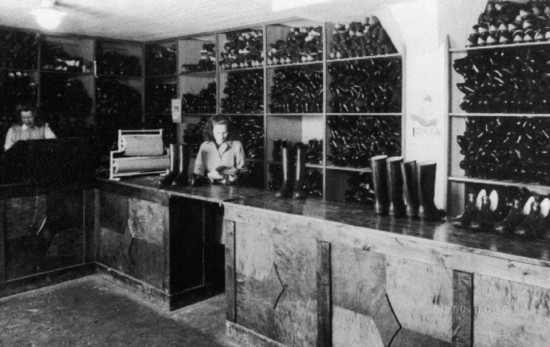

Other industries included flour mills, the dairy industry (which produced over 30,000 tons of butter and 10,000 tons of cheese, most of which was exported). Finland also produced a large amount of leather, with approx. ninety shoe plants producing 4.8 million pairs of shoes annually. And then there was the very visible contribution of Finnish architects and designers to architectural and furniture design which was rapidly gaining respect and being imitated around the world. Alvar Aalto, Erik Bryggman, Sigurd Frosterus, Armas Lindgren, Valter Jung and Eliel Saarinen among others. Here’s a few examples of their work:

Alvar Aalto’s Helsinki Olympic Stadium (Helsingin Olympiastadion)

Athletics have always held a particular importance in Finland and in the minds of the Finns. The first sports associations were founded as long ago as the end of last century, and from the beginning of the twentieth century the Finnish nation has been animated by a great zeal for sports.

The Stadium arena, which has been described as the most beautiful in the world, was the product of an architectural competition. Architects Yrjö Lindegren and Toivo Jäntti won the competition with their clearly lined functionalistic style design

Finland participated in the international Olympia movement even before the country gained independence in 1917. The Finns’ excellent results in the Olympic Games of the 1920’s fostered the dream that one day it would be possible to hold the Games in Helsinki. The Stadium Foundation, established 1927, started to implement this dream and their first and foremost task was to get a stadium built, which would permit Helsinki to host the Summer Olympics. Building began on February 12, 1934, and the Stadium was inaugurated on June 12, 1938.

The 1940 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XII Olympiad were originally scheduled to be held from September 21 to October 6, 1940, in Tokyo, Japan. When Tokyo was stripped of its host status for the Games by the IOC after the renunciation by the Japanese of the IOC’s Cairo Conference of 1938, due to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the IOC then awarded the Games to Helsinki, Finland, the runner-up in the original bidding process – much to the delight of Finns. The Games were scheduled to be staged from July 20 to August 4, 1940 but were cancelled after the Second World War broke out.

The Emergence of Nokia Ltd (Nokia Oy)

In 1927, three companies, which had been jointly owned since 1922 (Finnish Rubber Works-Suomen Gummitehdas Oy, Finnish Cable Works-Suomen Kaapelitehdas Oy and Nokia Company- Nokia Aktiebolag) were merged to form a new industrial conglomerate named Nokia Oy. Through the late 1920’s and 1930’s, Nokia Oy was involved in many industries, producing paper products, car and bicycle tires, footwear (including rubber boots and boots for the Finnish Army), communications cables, electricity generation machinery, gas masks for the Finnish Army), aluminium and chemicals. Each business unit had its own director who reported to the Nokia Corporation President.

In 1927, three companies, which had been jointly owned since 1922 (Finnish Rubber Works-Suomen Gummitehdas Oy, Finnish Cable Works-Suomen Kaapelitehdas Oy and Nokia Company- Nokia Aktiebolag) were merged to form a new industrial conglomerate named Nokia Oy. Through the late 1920’s and 1930’s, Nokia Oy was involved in many industries, producing paper products, car and bicycle tires, footwear (including rubber boots and boots for the Finnish Army), communications cables, electricity generation machinery, gas masks for the Finnish Army), aluminium and chemicals. Each business unit had its own director who reported to the Nokia Corporation President.

Nokia’s history starts in 1865 when mining engineer Knut Fredrik Idestam established a groundwood pulp mill on the banks of the Tammerkoski rapids in the town of Tampere, in southwestern Finland, and started manufacturing paper. Born in 1838 in Finland, Idestam’s training was in Mining, in which he held a Master’s degree. Following in his father’s footsteps, he planned a career as a civil servant in the Board of Mines of the Grand Duchy of Finland. In 1863-64, on a Finnish Senate (government) scholarship, Idestam undertook further studies in basic metals in Germany at the School of Mines (Bergakademie) in Freiberg, Saxony. While there, he was appointed as a mining engineer at the Finnish Board of Mines. But as early as the summer of 1864 his career plans changed. On his way through the Harz Mountains on his return trip from Freiberg, he visited a groundwood mill. This was a new invention: a factory which produced raw material for paper from wood. The process and equipment had been developed by the paper manufacturer Heinrich Voelter. The plant that Idestam saw had already reached the stage where it was capable of commercial production.

The demand for paper was increasing rapidly in the industrialising world – in Europe and North America. But production could not grow, because there was a shortage of the rags used as raw material and there was no way of increasing the supply. Idestam believed that Voelter’s solution to the raw-material problem was the correct one. He realised the importance of this innovation for Finland. There was an unlimited supply of raw material in Finland’s forests, and amidst the woods were rapids and waterfalls that could provide power for mills. As soon as he returned to Finland he ordered machines designed by Voelter from Germany, and he was granted an operating permit by the Senate on 12 May 1865, the date which today’s Nokia group of companies regards as its foundation day. The mill began production beside the lower falls of the Tammerkoski Rapids in Tampere early in 1866.

Idestam was not the first in his field in Finland. The pharmacist Achates Thuneberg had established a groundwood mill near Viipuri in 1860. Thuneberg’s plant had been developed in Viipuri – apparently independently of Voelter – and had been built in Finland. But Thuneberg was not successful: his mill was not as good as Voelter’s, and the small-scale venture soon petered out. In contrast, Idestam was successful and attracted competitors. Like Voelter in Germany, Idestam had to market his product energetically. Wood pulp was cheaper than rag pulp, but paper manufacturers and consumers regarded it as an inferior substitute – as ‘wood rag’. From the Frenckell (rag) paper mill in Tampere, Idestam ordered paper whose fibres consisted of equal parts of rag and his pulp. In December 1866 the Tampereen Sanomat became the first newspaper in Finland to be printed on paper containing wood. The Helsingfors Dagblad in Helsinki soon followed suit.

Idestam exhibited his groundwood at the 1867 Paris Exhibition and was awarded a Bronze Medal. This was the decisive breakthrough, as Idestam himself stated later. Voelter’s mill received a Gold Medal at the same exhibition. It was only at this point that the world realized the importance of Voelter’s process and equipment, and they began to come into more general use. Idestam’s first competitor in Finland was the Tampere pharmacist Gustaf Adolf Serlachius, who had become familiar with the field as the manager of Idestam’s mill, Idestam himself being prevented from running it because of his official post. Serlachius founded a mill at Mänttä in 1868. Tampere lost yet another pharmacist to the paper industry when Edvard Julius Granberg established a groundwood mill and paper mill at Valkeakoski in 1871. In 1868 Idestam built a second mill at Nokia, fifteen kilometres west of Tampere by the Nokianvirta river, which had better resources for hydropower production. In 1902, Nokia added electricity generation to its business activities.

With industrialisation, the demand for paper and cardboard for the rapidly expanding cities and offices soared and Nokia was soon exporting paper, first to Russia, then to England, France and even China. A number of groundwood mills were established in Finland in the early 1870s. Finland had been some twenty years behind Sweden and Norway in the sawmill industry, but the wood-pulp industry began at the same time and developed at the same pace in all three Nordic countries. From the early 1870’s to the beginning of the First World War, the share of the chemical forest industry in Finland’s total exports rose from zero to 20 percent, and at the same time the value of Finland’s total exports increased tenfold.

Idestam transformed his firm into a share company in 1871. With his close friend Leo Mechelin, Finnish statesman and Finland’s most prominent public figure in the late 19th century, he founded Nokia Ltd and transferred all activities to Nokia, where a new mill was built. Idestam’s mills and Nokia Manor and its interest in the Nokia Rapids, which had been acquired by Mechelin, were transferred to the new company. Idestam owned well over half the shares in the firm. He resigned from the Board of Mines and his position there as Master of the Mint and devoted himself entirely to managing Nokia Ltd. Mechelin gave him important support by attracting capital investment and funding.

The development of Nokia Ltd proceeded well. Idestam was a cautious business manager, and his financial planning allowed for future bad times. Although Nokia’s investments in expanding its production and increasing the degree of processing were large, Idestam, unlike many other pioneers of Finnish industry, coped with the crises that arose, and in the early 1880’s three paper machines were built at Nokia, as well as Finland’s first sulphite pulp mill in 1885. The first sulphate pulp mill had already been established earlier at Valkeakoski – in 1880. Chemical wood-pulp now replaced cloth-pulp as a raw material for almost all paper qualities. By the late 1880’s Nokia was processing all of its groundwood and chemical wood-pulp into paper.

On Idestam’s initiative and under his leadership, the paper-industry magnates founded their producers’ organisations: a cardboard association in 1874, a pulp association in 1875 and a paper association in 1892. These were cartels used by the Finns to divide up their most important marketing area, the Russian market, and to eliminate mutual competition. Idestam was the general manager and chairman of the Paper Association until 1903. He retired from the management of Nokia in 1896. He was succeeded as general manager by his son-in-law Gustaf Fogelholm and as chairman of the board by Leo Mechelin. Toward the end of the 19th century, Mechelin’s wishes to expand into the electricity business were at first thwarted by Idestam’s opposition. However, Idestam’s retirement from the management of the company in 1896 allowed Mechelin to become the company’s chairman (from 1898 until 1914) and sell most shareholders on his plans, thus realizing his vision. In 1902, Nokia added electricity generation to its business activities.

However, the collapse of Tsarist Russia and the subsequent Russian Civil War meant that Nokia’s primary market for paper had ceased to exist and in the immediate post-war period, Nokia faced bankruptcy. To ensure the continuation of electricity supply from Nokia’s electrical generators, Finnish Rubber Works acquired the business of the now insolvent company.

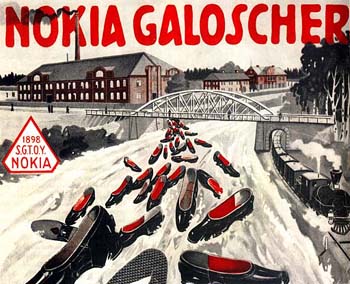

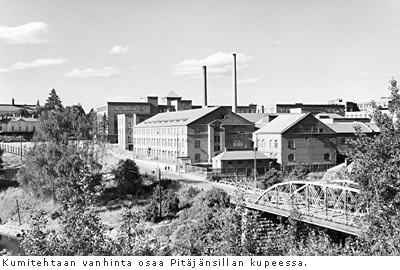

Finnish Rubber Works (Suomen Gummitehdas Oy) was founded in 1898 by Eduard Polón, as a manufacturer of galoshes and other rubber products such as rubberized fabrics – this company later became Nokia’s rubber business. At the beginning of the 20th century, Finnish Rubber Works decided to move from Helsinki into the countryside to reduce labour costs. The first idea was to move the production to Pori, but it did not work for the company. On the way back from Pori, company representatives, the Technical Director, and Dr. Antero Pentzin stopped to admire Nokia. The recently completed electrical power station, the rail link to Tampere and Pori, as well as low labor costs led to the company’s management deciding on a site next to Nokia – with a key deciding factor being access to cheap electricity.

Suomen Gummitehdas Oy established its factories near the town of Nokia and began using Nokia as its product brand name. Very quickly, raincoats and galoshes gained popularity in urban and rural areas. Rubber products were in demand not only by the consumer, but also in the business market. Due to industrialization there was a demand for a variety of equipment, which meant that the need for all kinds of rubber products.

Eduard Ulrik Vilhelm Polón was born on 16/06/1861 in Nastola (his father was the sheriff). He graduated from secondary school in Porvoo Lyceum in 1880, was awarded a degree seven years later and received the title of Master of Laws in 1890. After graduating, he worked as a lawyer in Helsinki, but also worked as an additional rapporteur for the Senate Finance Department and the Clerk vankeinhoitohallitukseen. He married the beautiful and musically talented Edition Ahnger with. whom he raised a family of six children. Polón loved children very much and was grieved by the death of his son Artur. His wife, who suffered from poor health, passed away in 1915, when Polón was left alone with five of their own children and four orphaned children of his brother’s.

In 1898, Eduard Polón founded Gummitehdas as a Finnish limited liability company, whose managing director was appointed. A supporter of Finnish nationalism and opposed to Russian oppression, Polón was forced out of office and at the same time, he decided to give up on his civil service career and move on to business, industry and politics. He was elected to the Diet in 1905 where his main objective was the restoration of Finnish autonomy. In 1916, Polón was deported to Russia, together with his son. Once there, however, he met with business companions and relatives, and thus managed Gummitehdasta, as well as monitoring his other investments, at a distance. After returning to Finland, Polón was offered the title of Counsellor of Mining and also the office of Governor of Häme province governor, but he refused these positions.

In his final years Polón supported charity, making significant personal donations to the working class relief and pension fund. Polón resigned in November 1929 as Chief Executive Officer of Kumitehdas due to increased paralysis. He died in the autumn of 1930.

The third company that went into the making of the Nokia conglomerate was Finnish Cable Works, founded by Arvid Wickström in 1912 as a producer of telephone, telegraph and electrical cables. In 1922, Finnish Rubber Works acquired Finnish Cable Works.

Despite their reputation of being reticent, the Finns were among the forerunners in the world in the use of the telephone. The first telephone line was erected in Helsinki towards the end of 1877; only 18 months after the telephone had been patented in the United States. The first telephone company was founded in Helsinki in 1882, and 1930 a total of 815 local telephone companies had been set up in Finland. In most other countries telephony was regarded as a successor to telegraphy and hence became a state monopoly. Telephones first arrived in the largest towns, then gradually spread to smaller towns and the surrounding countryside. In urban areas telephones grew common quite rapidly. At the turn of the century Helsinki had 3.3 phones per 100 population, which was considerably more than in other towns. By 1930 there was approximately one phone for every six people.

Measured with any indicators, private telephony activity was many times more extensive than that of the State. For example, in 1932 State telephone companies had 227 exchanges whereas private telephone companies had as many as 1,998. Likewise, in the same year the State had 1,763 “subscriber apparatuses” but private telephone companies had 133,456. At the time, Telephone Services in Finland were an open market, with the state-owned telecom company having a monopoly only on trunk network calls, while most (c. 75%) of local telecommunications was provided by telephone cooperatives, with most of the actual telephones and switches being purchased from the Swedish Ericsson Company. In 1930, the newly appointed President (and former Technical Director) of Finnish Cable Works, Verner Weckman, made a case for Nokia to move into the design and maufacture of telephony equipment for the Finnish market. With the support of the Finnish Government (by way of placing orders and placing tariff barriers on imports), Nokia quickly established itself in the limited Finnish market for such equipment, at the same time gaining experience in the design and manufacturing of telephones and the new automatic switches that were slowly penetrating the telephony market.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the world telephone markets were being organized and stabilized by many governments. The fragmented town-by-town systems which had grown up over the years, serviced by many small private companies, were being integrated and offered for lease to a single company. Finland was no exception and in 1932, Nokia was awarded the contract for Finnish Telephone Services nationwide. Within two years, Nokia had expanded into Estonia and had begun selling telephones and switches to the other Baltic States and to Poland. As part of the trade deals with the USSR, in 1935 the Government secured a contract for the delivery of automated switches to the USSR, a minor order for the established European and American manufacturers but a significant sale for Nokia. By 1935, Finnish Cable was securely established as a small (by world standards) telephone equipment designer and manufacturer. And in 1935, influenced by Finnish Cables success in the communications field, the Defence Forces signed a research and development contract with Finnish Cable to design and develop a number of military communications devices for the Army and Air Force. The significance and impact of this R&D contract will be discussed in a later section.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland