At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Duchy of Finland was part of the Russian Empire, ruled by the autocratic Tsar Nicholas. Finnish Nationalism had been on the rise since the 1830’s and by 1900, resistance to Russian rule was growing, aided by the policy of Russification which had resulted in the sortovuodet – the “years of oppression” as the period from 1899-1917 came to be called. In those early years of the twentieth century, Tsarist-Russia and Imperial Japan were at loggerheads in China, with both countries expanding their influence and territorial acquisitions, leading directly to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. At the time, a desire by Finns for independence from Tsarist Russia was on the rise and the Japanese sought to both make use of this and to establish ties with the Finnish people. The cooperation between Finnish nationalists and Japan in what became known as “the Grafton Affair” (arranged between Finnish nationalist Konrad Viktor (Konni) Zilliacus and Motojiro Akashi, a Japanese military attache), survived the First World War in both Japan and Finland and were well remembered into the 1920’s and 1930’s.

The “Grafton Affair”

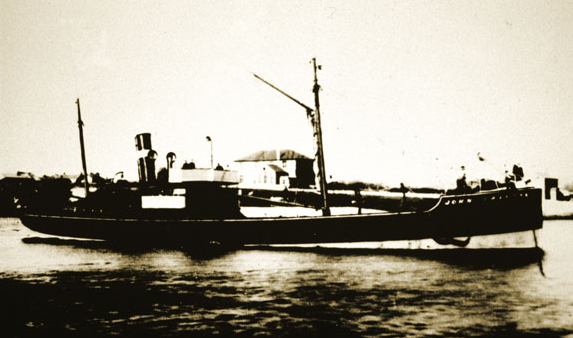

The “Grafton Affair” was an attempt to smuggle large quantities of arms for the Finnish resistance to the Imperial Russian regime in 1905. It came to be known as the “Grafton Affair” after the name of the steamship involved. The S/S John Grafton was a 315-ton ship built in 1883. It was bought by the japanese army officer and intelligence agent Akashi Motojiro in 1905 to aid the Finnish nationalists in an armed uprising in Finland against Tsarist Russia. Nationalism in Finland had been growing and as the Russification in Finland increased, Finnish resistance activist Konni Zilliacus organized the smuggling of weapons into Finland in 1905 with the assistance of the Japanese, who were fighting the Russians in the Far East.

With Japanese financing, the S/S John Grafton was bought, nominally in the name of a sympathetic London wine merchant. In London the ship was loaded with 15,500 Swiss “Vetterli” rifles (note that they were Model 1869/71s) and 2.5 million bullets that had been retired from the Swiss Army. The cargo also included 2,500 high-class English officer’s revolvers and 3 tons of explosives. According to the original plan, the weapons were to be transported via the Netherlands and Copenhagen to a meeting place in the Gulf of Finland, from where the journey would continue to St Petersburg. On arrival, a part of the cargo would be offloaded and given to Russian revolutionaries. The ship sailed to Flushing and on 28 July the ship was renamed the Luna. The wine merchant sold the ship to a non British firm on this day, but did not report it. However, a subsequent inquiry conducted by the Maritime Department of the Board of Trade in September was able to retrospectively remove the ship from the English register of shipping, avoiding embarrassment when its subsequent activities came to the attention of the Russian authorities.

After running into a few problems the route was changed, and the ship set course towards the Gulf of Bothnia and town of Kemi, where part of the cargo was offloaded. The journey continued to Jakobstad which, like Kemi, was a center of the Finnish nationalist resistance. The ship was guided into the rocky archipelago north of Jakobstad and the offloading of the weapons was conducted without any major problem. When the ship resumed its journey south, she ran aground. The crew started to salvage what remained of the weapons but it quickly became clear that the whole cargo could not be salvaged. Captain J.W. Nylander made the decision to blow up the ship to avoid it ending up in the hands of the Russian authorities and on the afternoon of 8 September 1905 the ship was blown up with three powerful charges. The sound from the explosion was heard far way, some accounts mention as far as 50 miles distant. Nevertheless the Russian gendarmes learned of the operation. Rifles from the ship were recovered by divers and some of those stored ashore were found and confiscated.

Despite the harsh censorship of the Russification period, widespread speculation about the event occurred in both Finnish and foreign newspapers. Even though the plans for the “John Grafton” did not pan out, the event is considered one of the first concrete actions for an independent Finland. In 1930 a monument was unveiled at Orrskär in Larsmo to commemorate the event. To this day parts of the cargo and ship lie at the bottom of the gulf. The weapons that had been offloaded started to spread out into the villages (where amongst other things they were used for elk hunting) and and later became part of the White Guard (Suojeluskuntas) armory when they were founded in 1917. The already old weapons were never used in any military action. The Russian authorities salvaged parts of the cargo using divers.

During the following years a further small number of Vetterli rifles were acquired and smuggled to Finland. The Vetterlis featured in the secret preparations for the Finnish uprising but when the War of Independence started in the winter of 1918 the rifles were considered hopelessly outdated and lacked ammunition.Nevertheless, more Vetterli rifles were obtained during the war when Russian arms depots were captured and rifles confiscated 12 years earlier were found.The Finnish Defense Forces never adopted the Vetterli rifle as a standard service weapon but there was a small number stored in arms depots until the 1950’s.

The location of the wreck of the S/S John Grafton is well known and debris is spread across the bottom over a wide area. Amateur divers have in the past recovered rifles and ammunition but apparently these are no longer found. In Central Bothnia there are still a number of “Graftonkivääreitä.”

The two key participants in the Grafton Affair were Finnish nationalist Konrad Viktor (Konni) Zilliacus and the Japanese intelligence agent Akashi Motojiro.

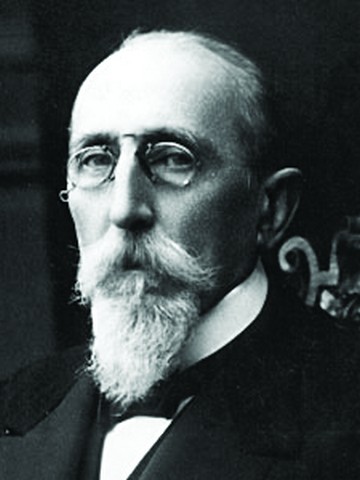

Konrad Viktor (Konni) Zilliacus (18 December 1855, Helsinki – 19 June 1924, Helsinki) was a Finnish independence activist, writer and the leader of a daring anti-Russian Finnish nationalist group, the Suomen Aktiivisen Vastustuspuolueen or Finland Active Resistance Party before and during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) and the Russian Revolution of 1905, who inspired a later generation of Finnish anti-Russian activists. His father, Henrik Johan Wilhelm Zilliacus was a doctor and from 1875 a Senator and Deputy Head of the Civil Editorial Board. His mother was Ida Charlotta, nee Söderhjelm. Zilliacus matriculated from secondary school in 1872 at age 16 and joined the Vyborg Students’ Association. At university, he read law and completed a legal degree in 1877. In 1878 at the age of 23 he married a much older woman, Lovisa Adelaide Ehrnrooth, who was a widow with seven children from a previous marriage. They settled into the Ehrnrooth townhouse and he worked in the Court of Appeals from 1877 and also worked as a teacher, in the Governor-General of Finland’s Office, as a civil servant and in 1880 as a ferry manager. After a year as ferry manager, he started a career as a farmer in 1881, buying a farm. In 1883 he bought more land jointly with a bank director named Abel Lanêdin. He bred horses, started a dairy farm and went heavily into debt. He managed to avoud bankruptcy but these financial difficulties led to his taking a new career direction.

In 1989 Zilliacus organized Finland’s participation in the World Exhibition in Paris, which he saw as an opportunity to highlight to the world Finland’s independent nationality. In May 1889, he traveled to the USA as correspondent for the Hufvudstadsbladet magazine, writing articles about the American Indian wars and migrants lives. After spending two years in America, he informed his family that he was unable to return to Finland, and divorced his first wife Lovisa Adelaiden. His now former wife was fortunately able to rescue much of the Ehrnrooth family assets.

In America, he worked in a variety of jobs, as a Supervisor and once as a sewer digger for $1.50 a day. He then worked for a number of magazines as a correspondent, ending up in Chicago as a reporter for the “Svenska Tribune.” In 1891 he traveled to Pine Bridge, South Dakota, as the Svenska Tribune correspondent reporting one the Sioux Indians rebellion. He was present at the Pine Bridge peace negotiations, counting 10,000 Sioux Indians on his arrival. Based on his Svenska Tribune Indian War experiences he later wrote the 1898 book “Indiankriget”, which was published in Finnish in 1899 under the name Indian War – Reports from the U.S. border in 1899. In 1893 he married Lilian Graefin, the 20-year-old daughter of Anthony Graefin, a wealthy German-American businessman.

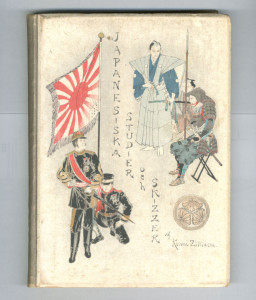

At the end of 1893, he traveled with his wife to Morocco, Italy and Egypt and also traveled around India. Then they traveled to Japan where they lived for two and a half years and where two of their sons were born. There he spent his time in the company of Japanese artists. In Japan he wrote a book, “Japanesiska studier och skizzer” which was published in print in 1896 in Helsinki. In October 1896 Konni Zilliacus and his family left Japan, arriving in Paris the following spring. While in Paris he wrote the books ” Siirtolaisia” (”Immigrants” – 1896), “Siirtolaisseikkailuja” (1898) and ”Taavetti Anttilan kohtalo ynnä muita kertomuksia Amerikan elämästä.” (“Taavetti Anttila’s fate, and others reports on American life”), published in 1898. In 1898, he went back to Finland. The following year he became a journalist, writing for “Nya Presse,” which was banned on 29 June 1900. Zilliacus continued writing articles for different magazines in which he mainly discussed Finnish and Russian policy viewed from a political background.

In 1902 he moved to Stockholm and from 1904 he was an organizer of the Suomen Aktiivisen Vastustuspuolueen or Finland Active Resistance Party and also served as editor of its widely disseminated newspaper. As one of the early leaders of the Finnish independence movement, he cultivated relations with the Russian revolutionary movement, and smuggled his newspaper and other revolutionary literature from Sweden to Finland on his yacht, as well as weapons. His book ”Det Revolutionära Ryssland” (1902) was translated into a number of languages. When the Russo-Japanese War broke out, Zilliacus contacted the Japanese military attache in Stockholm (and former military attache in St Petersburg, Colonel Motojiro Akashi, and proposed Japanese support to buy and ship arms to the Finnish nationalist resistance.

“Konni Zilliacus”, a biography by Herman Gummerus, was published in 1933, 9 years after Zilliacus’ death

Colonel Motojirō provided large sums of money to assist him in developing subversive activities in an attempt to create domestic political instability during the Russo-Japanese War. Zilliacus met with Polish independence activist Roman Dmowski and Russian revolutionary leader Georgii Plekhanov as well as other dissidents. With Japanese assistance, Zilliacus organized a conference of Russian revolutionary organizations in Paris in September 1904, which agreed upon a program of legal and illegal means to replace the current autocracy with a democratic government. Following the abortive uprising in January 1905, he organized a second conference in Geneva in April 1905, with the participation of eleven revolutionary organizations. With Japanese financing, the steamer SS John Grafton was purchased and a large quantity of arms, which they unsuccessfully attempted to smuggle into Finland in 1905. Zilliacus moved back to Helsinki in 1906; however, once his connections with the Japanese became public, he was forced to the United Kingdom with his family in 1909. His son, Konni Zilliacus was a Labour Party Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom for Gateshead. During WW1, he was a supporter of the Finnish Jaeger Movement. After Finland’s independence, Zilliacus returned to the country in 1918. He died in 1924 in a private nursing home in Helsinki. In his final days, he wrote a memoir of his underground activities, as well as a cookbook. Over the years, as the interpretation of Finnish history changed following independence, Zilliacus’ reputation and prestige would grow.

Suomen Aktiivisen Vastustuspuolueen / Aktiva Motståndspartiet / Finland Active Resistance Party

The years 1904-1908 were a period of oppression in Finland and the Suomen Aktiivisen Vastustuspuolueen acted as the party which opposed Russification and was in favor of Finland’s independence from Russia through violent action if necessary. Zilliacus founded the new party, with the inaugural meeting being held on 17 November 1904. Herman Gummerus was elected Chairman of the Party, which also had its own fighting organization whose task was to plan and carry out acts of terrorism. A number of different nationalist groups joined the Party. When the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 broke out, Konni Zilliacus contacted the Japanese military attache in Stockholm, Colonel Motojiro Akashi and proposed a joint action against the Russian government by different nationalist groups within the Russian Empire and Japan. He toured Europe to establish support from different exile groups on the subject, and organized in collaboration with the Poles the subversion of 10,000 Polish soldiers serving in the Russian Army in Manchuria on the Yalu River front. The various revolutionary groups organized a joint meeting in Paris in October 1904 and again in April 1905 in Geneva. The meetings resulted in and agreement to initiate an armed rebellion against Russia. In Finland, Leo Mechelin led a constitutional resistance but did not accept the use of violence and so passive resistance was organized instead, with the Finnish resistance refusing to ratify the agreement reached at the Paris and Geneva meetings.

The party had its own magazine called Frihet (Freedom) which was distributed secretly in Finland and also published the weekly magazine Framtid. The Party smuggled literature, weapons and explosives into Finland, with the best known of the smuggling attempts being that involving the SS Grafton in September 1905, with arms and ammunition financed by Japan and intended for both Finnish and Russian Tsarist regime opponents. Party activists assisted Russian revolutionaries hiding in Finland by organizing homes and passports as well as assisting with travel arrangements. A Russian Socialist Party meeting was held in Tampere in November 1906 and the Socialist Revolutionary Congress was held there in February 1907.

In 1905, Party activists made a number of unsuccessful murder attemptes against the Russian bureaucracy. In March 1905 Matti Reinikka tried to shoot the provincial governor of Vyborg, Mjasojedovin, but only managed to wound him. On 19 July 1905 student and Party activist Artturi Salovaara threw a bomb towards the assistant of the Governor-General of Finland, V F Deutrichia who saved himself at the last minute by throwing himself aside. During the summer, the assassinations of the Governor of the Province of Häme and the Governor and Viborg County Governor Pappkovia were attempted. Painter Asarias Hjorth threw a bomb toward Pappkovia but the bomb turned out to be ineffective.

In September 1905 more bombs exploded in Helsinki at the central police station and in front of the Vaasa governor’s house. In Helsinki a small group of secondary school students formed the Verikoirat (Blood Dogs) activist group and carried out a number of attacks in the 1905 period. In August 1905 a group shot at Finnish police and in September they wounded two Russian gendarmes. Thereafter, the group fired at two Russian police officers, one of whom died of wounds as well as blowing up a police station with a bomb. The Verikoirat (Blood Dogs) were led by Student Union member and later pharmacist, K. G. K. Nyman. In the same year, four graduate activists planned to murder Tsar Nicholas II when he was on a hunting trip to Koivisto. The group arrived at Koivisto but Nikolas had already returned to St. Petersburg. Instead, one of the group, Kalle Procope, managed to murder a Lt-Col Kramarenkon.

The activities of the activists began to gradually wane. In the party congress at Oulu in December 1906 the Social Democratic Party denied membership to members of an underground operation and to those who participated in terrorist acts. Also, many activists finally decided to abandon the use of violence as parliamentary reform opened new possibilities for action. The Suomen Aktiivisen Vastustuspuolueen ceased activities by 1908 at the latest.

OTL Note: For more on Zilliacus, read his (Finnish language) biography, ”Konni Zilliacus” by Herman Gummerus, Gummerus, Porvoo 1933

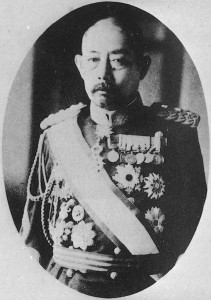

Baron Akashi Motojiro

Baron Akashi Motojiro (1 Sept 1864-26 Oct 1919), whom we have mentioned above a number of times, was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army. He graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1889, was assigned to the Imperial Guard Division and attached to the staff of General Kawakami Sōroku during the First Sino-Japanese War. His primary duty was information gathering, and in that capacity he traveled extensively around the Liaodong Peninsula and northern China, Taiwan and Annam. Towards the end of the war, he was promoted to Major. After the Sino-Japanese War, he was dispatched as a military observer to the Philippines during the Spanish-American War, and during the Boxer Rebellion, he was stationed out of Tianjin in northern China. Around this time, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel.

Akashi Motojirō, Rakka ryusui: Colonel Akashi’s Report on His Secret Cooperation with the Russian Revolutionary Parties during the Russo-Japanese War

Akashi was sent as an itinerant military attaché to Europe at the end of 1900, visiting Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, staying in France in 1901, and moving to Saint Petersburg, Russian, in 1902. As a member of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Services, Akashi was involved in setting up an intricate espionage network in all major European cities, using specially trained operatives under various covers, members of locally-based Japanese merchants and workers, and local people either sympathetic to Japan, or willing to be cooperative for a price. In the period of growing tensions before the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, Akashi had a discretionary budget of 1 million yen (an incredible sum of money in contemporary terms) to gather information on Russian troop movements and naval developments. While based at Saint Petersburg, he recruited the famous spy Sidney Reilly and sent him to Port Arthur, to gather information from within the Russian stronghold on its defenses. After the start of the war, he used his contacts and network to seek out and to provide monetary and weaponry support to revolutionary forces attempting to overthrow the Romanov dynasty.

Akashi was also known for his talents as a poet and as a painter, interests that he shared with fellow spy and close friend General Fukushima Yasumasa. It was also a shared interest in poetry and painting that enabled him to cultivate Sidney Reilly into working for the Japanese. Narrowly escaping capture and assassination by the Ochrana, the Tsarist Russian Secret Service, several times even before the start of the war, Akashi relocated to Helsinki in late 1904, although he traveled extensively to Stockholm, Warsaw, Geneva, Lisbon, Paris, Rome, Copenhagen, Zurich and even Irkutsk. Akashi helped funnel funds and arms to selected groups of Russian anarchists, the secessionists in Finland and Poland, and disaffected Moslem groups in the Crimea and Russian Turkestan. Akashi is also known to have met with Konni Zilliacus in Stockholm and with Lenin, then in exile in Switzerland. It is widely believed in Japan that Akashi was behind the assassination of Russian Interior Minister Vyacheslav von Plehve (whom many in Japan held responsible for the war), the Bloody Sunday Uprising and the Potemkin Mutiny. General Yamagata Aritomo reported to Emperor Meiji that Colonel Akashi was worth “more than 10 divisions of troops in Manchuria” towards Japan winning the war. Akashi was promoted to Colonel at age 40.

In 1905, just prior to the end of the war, he was recalled to Japan, divorced his wife, remarried, and joined the ground forces in Korea as a Major-General in command of the 14th Infantry Division.In 1918, Akashi was promoted to General and appointed by Prime Minister Terauchi as the Governor-General of Taiwan. He also received the title of Danshaku (Baron) under the kazoku peerage system. During his brief tenure as Governor-General, Akashi devoted significant efforts to improving the infrastructure and economy of Taiwan, and is especially remembered for his electrification projects, the creation of the Taiwan Power Company, and for planning the Sun Moon Lake hydroelectric power plant. The “lake” was originally a swamp. Akashi had concrete pipes built to introduce water from the nearby Muddy Water River, and built a huge dam with water siphoned from the river. The dam and its surrounding area, known as “Sun Moon Lake” today, is a highly scenic area – the mainland Chinese government, without the consent of the Taiwanese, even today calls it one of China’s top ten scenic sites. Akashi’s greatest contribution to Taiwan, however, was the construction of the “Ka-Nan Irrigation System” totaling more than 16,000 miles (26,000 km) of irrigation network and which cost the Taiwan government at that time more than one year’s budget.

Akashi fell ill and died a little over a year after taking office while visiting his home in Fukuoka, becoming the only Governor-General of Taiwan to die in office. In his will, Akashi expressed his desire to be buried in Taiwan to “serve as a national guardian, and a guardian spirit for the people of Taiwan”. Akashi was buried at a cemetery in Taihoku (modern day Taipei City), becoming the only Japanese Governor-General to be buried in Taiwan. The Taiwanese donated the equivalent to roughly three million modern day U.S. dollars for construction of a memorial, and as a support fund for his family, because Akashi himself was too uncorrupt to leave anything behind from his position. His remains were exhumed in 1999 and re-interred at the Fuyin Mountain Christian Cemetery in Sanzhi Township, Taipei County (now New Taipei City). Akashi’s death has spawned a massive number of conspiracy theories. The flamboyant exploits (both real and imagined) of “Colonel Akashi” have been the subject of countless novels, manga, movies and documentary programs in Japan, where he has been dubbed the “Japanese James Bond”.

OTL Note: for more on the Zilliacus-Akashi connection, read “Northern Underground: Episodes of Russian Revolutionary Transport and communications through Scandinavia and Finland 1863-1917” by Michael Futrell, Faber and Faber, 1963. Also read “A History of the Japanese Secret Service” by Richard Deacon (1986).

Between 1905 and the end of WW1, there was little further contact between Japan and the Finnish Nationalist movement. After the 1905 Russo-Japanese war, Japan ceased active hostilities with Russia and had no interest in stirring further disruption within Tsarist Russia. In WW1, Japan was more or less neutral on the side of the allies and it was only after the war ended that Japan again became involved, somewhat peripherally, with Finland. Japan was of course at that time rather more involved in the anti-Bolshevik intervention in Siberia, where her troops fought alongside American, Canadian and other British Commonwealth soldiers over the course of the intervention. More on this relationship in a subsequent post…..

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland

Pingback: Japan's relations with Finland 1919-1944