How many of us today know that there were Finns in the Boer War in South Africa – who fought with the Boer forces? Well, they did, within the ranks of the Skandinaviska Karen (the Scandinavian Corps) of volunteers who were a part of the Transvaal militia. Following the outbreak of war, a meeting was held in Pretoria on 12 October 1899, which led to the formation of the Skandinaviska Karen (the Scandinavian Corps). The service of this unit was then offered to the Government of the Transvaal, which gladly accepted. Until then, the Boers had viewed the Scandinavians as uitlanders (foreigners) who tended to side with the British.

That there were Finns in the Boer War who fought on the side of the Boers is now a piece of history unknown outside of Finland, and little known even in Finland. But it was not always so. Ninety odd years ago now, on December 11th, 1924, the Republic of Finland celebrated a very special anniversary – the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Magersfontein, part of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. The state and the military establishment hosted this anniversary at the Officers’ Casino Building in the Katajanokka neighborhood of Helsinki and among the guests of honour were Lauri Malmberg, the minister of defense, and Per Zilliacus, the chief of staff of Finland’s Civil Guard. The Suojeluskuntas (Finnish Civil Guard) also sent a wreath tied with blue-white ribbons to South Africa, where it was laid at the monument on the battlefield of Magersfontein.

The Battle of Magersfontein was the second of the three battles fought over the “Black Week” of the Second Boer War. It was fought on 11 December 1899 at Magersfontein near Kimberley on the borders of the Cape Colony and the independent republic of the Orange Free State. General Piet Cronje and General De la Rey’s Boer troops defeated British troops under the command of Lieutenant General Lord Methuen, who had been sent to relieve the Siege of Kimberley). The conservative Finnish newspaper “Uusi Suomi” (New Finland) advertised the event on its front page, and the periodicals of the Suojeluskuntas published anniversary articles on the conflict between the Boer republics and the British Empire. The celebration opened with the Finnish Naval Orchestra’s performance of “Kent gij dat volk,” the old national anthem of the Transvaal.

The Finnish Naval Orchestra played “Kent gij dat volk” – the National Anthem of The Transvaal

Just why were Finns in Finland commemorating the Battle of Magersfontein, a Boer War (1899-1902) battle fought in Africa between two nations, Britain, and the Boer Republics of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, neither of whom were enemies of Finland?

The Origins of the Boer War

Europeans first inhabited South Africa in 1652 when the Dutch East India Company sent out a ship to establish a supply depot to service its trading vessels passing the Cape of Good Hope. Some of these Dutchmen became farmers and gradually expanded into the hinterlands to the north and east. In 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars, Holland was allied with the French, and the area was invaded and annexed by Great Britain. Later, as more British settlers arrived and conflicts resulted, many of the Boers (whose name means “farmers” in Dutch) embarked on what is called the “Great Trek”, moving further inland in 1838 and founding two new independent states – the Orange Free State and the Transvaal Republic.

The British made a move to annex the Transvaal in 1877, but the Boers defeated the British Imperial forces in the First Anglo-Boer War of 1880-1881. However, near the turn of the 20th Century, major fighting broke out between the British and the two Boer Republics. The origins of the war were complex, with more than a century of conflict between the Boers and the British Empire in the background, but the immediate cause was the question as to which nation would control and benefit most from the very lucrative Witwatersrand gold mines in the Transvaal. Gold made the Transvaal potentially the richest nation in southern Africa; however, the country had neither the manpower nor the industrial base to develop the resource on its own. As a result, the Transvaal reluctantly acquiesced to the immigration of uitlanders (foreigners), mainly from Britain, who came to the Boer region in search of fortune and employment. This resulted in the number of uitlanders in the Transvaal potentially exceeding the number of Boers, and precipitated confrontations between the earlier-arrived Boer settlers and the newer, non-Boer arrivals.

Given the British origins of the majority of uitlanders and the ongoing influx of new uitlanders into Johannesburg, the Boers recognised that granting full voting rights to the uitlanders would eventually result in the loss of ethnic Boer control in the South African Republic. In September 1899, British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain demanded full voting rights and representation for the uitlanders residing in the Transvaal. Paul Kruger, the President of the South African Republic (the Transvaal), issued an ultimatum on 9 October 1899, giving the British government 48 hours to withdraw all their troops from the borders of both the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, failing which the Transvaal, allied to the Orange Free State, would declare war on the British government.

The British government rejected the South African Republic’s ultimatum, resulting in the South African Republic and the Orange Free State declaring war on Britain. The Boer War had begun (in Afrikaans, die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, the “Second War for Freedom.” The official terms in Afrikaner historiography for the wars against the British Empire in 1880-1881 and 1899-1902 are the First and Second Wars for Freedom).

Early Finns in Africa

As far as is recorded, Finns first found their way to European colonies in Africa in the 18th century. Henrik Jacob Wikar (born in Kruunupyy in 1752, studied at the Academy of Turku in 1769) traveled to Holland and in 1773 was employed by the Dutch East India Company in Cape Town as a clerk in the hospital. Apparently somewhat of a gambler, he abandoned the job after two years (running away from gambling debts) and ventured into the unknown inland regions north of the Colony in the area of the Orange River where he stayed for four years. Wikar was one of the first Europeans to explore the Orange River and the first European to see the Augrabies Falls. His diary has been a valuable source of material for research into the early history of South Africa and the culture of the khoisan (bushman) natives Wikar was living with.

Another early Finn to Africa was August Nordenskiöld who in 1792 joined an expedition to Free Town in Sierra Leone to found a colony called ”New Jerusalem”. This utopian enterprise never materialized and Nordenskiöld died soon of exhaustion caused by diseases and maltreatment by the natives. The Belgian Congo also attracted a number of Finns, who were usually found working as engineers or mates on steamboats on the River Congo (shades of Heart of Darkness there). Finnish adventurers could be found in many african colonies from the end of the 19th century. The most famous of these was Carl Theodor Eriksson (1874-1940) who, after participating in the Boer war with the British Rhodesian troops, went on to discover rich mining areas in Katanga, the Belgian Congo.

In 1870, Finnish missionaries began working in Amboland (the German colony of South West Africa), now Namibia. Many of the Finnish missionaries stayed permanently in Africa. In South Africa itself, the mining industry in the 1860’s and 1870’s caused tremendous economic upheaval. By the close of the century deep-shaft mining in Transvaal had started to attract Finnish immigrants (in addition to many others). In the 1890’s emigration to South Africa, and especially to the “golden city” of Johannesburg, reached the proportions of an epidemic in Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia, with some 1,500 Finns known to have emigrated to South Africa before the First World War

Finns in the Boer War

The reason that independent Finland in 1924 celebrated a battle fought in a British colonial conflict in South Africa a mere 25 years previously was straightforward. Finnish volunteers had fought in the Battle of Magersfontein as soldiers of the Scandinavian Corps of the Boer Republic forces. The Scandinavian had its origins in the Scandinavian Organisation in the Transvaal, a group which had been founded by Axel Christer Helmfrid Uggla, a Swedish engineer, in the Spring of 1899. Uggla had worked on the Transvaal since 1890 as head of the Nederlandsch-Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg Maatschappij (NZASM) Railway Workshops in Pretoria.

The main purpose of the Scandinavian Organisation was to find work and housing for unemployed fellow Scandinavians and to raise funds to aid them. Following the outbreak of the Boer War, a meeting was held in Pretoria on 12 October 1899, which led to the formation of the Skandinaviska Karen (the Scandinavian Corps) of volunteers for service with the Transvaal militia. The service of this unit was then offered to the Government of the Transvaal, which gladly accepted. Until then, the Boers had viewed the Scandinavians as uitlanders who tended to side with the British.

Model 1888 Mauser rifles were provided by the Transvaal Government while clothes suitable for use as uniforms were bought by the Committee. On the first day of recruitment, 68 Scandinavians volunteered, including three for medical service (three Swedish women – Anna Lindblom, Elin Lindblom and Hildur Svensson) served as nurses in a separate ambulance unit). In all, 118 men eventually served in the unit; 48 Swedes, 24 Danes, 19 Finns, 13 Norwegians and 14 other miscellaneous nationalities, mainly Germans and Dutch. The Government provided ninety horses. For the logistics, three Voortrekker ox-wagons were acquired.

Officers and NCOs were elected (as was common within the Boer forces). As Uggla had been ordered by the Transvaal Government to transform the Railway Workshops into a Weapons Factory and Workshops, he was unavailable to take command of the company-sized force. The officers and NCOs appointed were:

- Johannes Flygare (Sweden), Captain (Veldkornet)

- Erik Stalberg (Sweden), 1st Lieutenant

- William Baerentzen (Denmark), 2nd Lieutenant

- Carl David Appelgren (Sweden), 1st Lieutenant-Quartermaster

- Adolf Claudelin (Sweden), 2nd Lieutenant-Quartermaster

- Gotthard Christensen (Denmark), Sergeant (Danish Troop)

- Johan Niklas Viklund (Finland), Sergeant (Finnish Troop)

- Norman Randers (Norway), Sergeant (Norwegian Troop)

- Charles Johansson (Sweden), Sergeant (Swedish Troop)

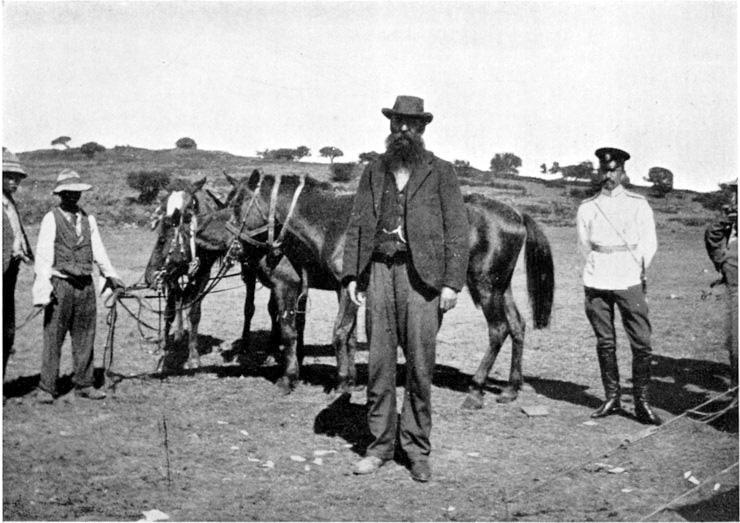

Captain Flygare was born in Natal, with Swedish parents. Before the war, he had been a land surveyor with the Transvaal Government. He spoke Afrikaans and some native African languages and had previously participated in military actions against the indigenous Africans. Lieutenants Erik Stalberg and William Baerentzen were members of the Central Committee and Stalberg had previously served as a Warrant Officer with the Royal Swedish Army. Stalberg was made responsible for military training. This was a difficult task, since most of the men had never seen a Mauser and few knew how to ride a horse, many having been sailors. After mobilisation, the Company was paraded before President Kruger, who addressed the troops and shook hands with all volunteers, probably on 16 October 1899, when it was ordered to the Mafikeng front.

The Scandinavian company in Pretoria, probably on 16 October 1899. Mr Uggla can be seen standing, first row far left.

In the first row centre, under the banner, is a group of five officers. They are, from left, 2/Lt QM Claudelin, 1/Lt Stalberg,

Cpt Flygare, 1/Lt QM Appelgren and 2/Lt Baerentzen. Except for Claudelin, all of these officers were killed or wounded and taken prisoner at Magersfontein, 11 December 1899.

To the Mafeking Front

On 16 October 1899, the Company, then comprising some 100 men and 130 horses, was moved by rail from Pretoria to Klerksdorp, where training was continued for another few days. Horse-riding was a challenge and Lieutenant Stalberg had no previous experience in this field. He was, however, instructed by a local police officer for some hours. On horseback, the troops continued moving southwards. Due to the poor horse-riding skills of the men, the march progressed slowly. In Polfontein, the Scandinavians were ordered to act as an escort for the ‘Long Tom’ siege-gun en route to Mafikeng.

On 21 October 1899, two volunteers, the Swede, Carl Hultin, and the Norwegian, Einar Olsen, were wounded, but no details are known. (Here, records of Hultin end, so he probably returned home, but Olsen was later killed at Magersfontein). On 23 October 1899, the Company joined the forces of General Piet Cronje at Rietvlei near Mafikeng. On 25 October 1899, the Company was ordered to take part in an assault on Mafikeng which was to be carried out by some 1,200 Boers under Commandant Wolmarans. This assault was unsuccessful and the Boers only managed to advance to about 500 metres from the enemy lines. Again, two volunteers were wounded, a Dane, Klaussen, and a Finn, Jacob Johansson. (About Klaussen, nothing more is known and he is not recorded on the nominal roll, whereas Johansson fought at Magersfontein and later died in 1900 as a prisoner of war on St Helena).

The next action was during the night of 2/3 November 1899, when Captain Flygare and 20 of the best trained Scandinavians, with about 80 Boers, infiltrated and held the British positions until 5 November, when a part of the British defence line was charged and taken, cutting off British artillery on what was referred to as ‘Cannon-kopje’. However, this position had to be abandoned and the Scandinavian company was then used as a scouting force and for demolition work over the next few days.

To Magersfontein

On 20 November 1899, General Cronje’s Boer forces, including the Scandinavian company, started moving in order to prevent the British under Lord Methuen from relieving the besieged town of Kimberley. The Company, by then in good control of their horses, made the ride back to Klerksdorp in half the time they had initially covered the distance. In Klerksdorp, fifteen new volunteers, brought there by Uggla, joined the Company, which then moved by train to Edenburg and from there to Jacobsdal on horseback. The Company was ordered to join General de la Rey at Scholtznek and, on the way, to serve as an escort for two Krupp field guns.

In Scholtznek, there followed rest period, during which the Company underwent additional training, while demolition teams were sent out to blow up the railway line to Kimberley. After scoring some success with this, General Cronje presented the Scandinavian company with a donkey-wagon loaded with explosives and trench tools. A demolition team of ten volunteers, headed by two Finnish experts, drove out with the wagon and mined the railway in two places about 20 km south of the Modder River.

After that, reconnaissance carried out on 6 December showed that the British forces were closing in. General de la Rey persuaded General Cronje to take up a defensive position at Magersfontein on 8 December and, two days later, the General inspected the Scandinavian company. On 10 December, Captain Flygare and two troops carried out reconnaissance. During the night of 10/ 11 December, approximately half of the Scandinavians manned an advanced outpost and the rest entrenched their defensive positions some 1,5 km further north-east.

The fight for the Scandinavian outpost at Magersfontein began on 11 December 1899 at 03.15am and was apparently a mistake. At about 02.00am, General Cronje had ordered Commandant Tolly de Beer to abandon the outposts, but this instruction had not been communicated to the Scandinavians. The Scandinavians repulsed the first British attack, but a second followed at 06.15am and lasted for half an hour. Captain Flygare was one of the first to be killed and Lieutenant Stalberg was wounded three times. Before losing consciousness, he ordered the troops to abandon the outpost. Lieutenant Baerentzen was also out of action, having been wounded twice. Lieutenant-Quartermaster Appelgren was not at the outpost, but was wounded in the main defence line and died some days later. Only one officer remained, Lieutenant-Quartermaster Claudelin.

The Company suffered heavy losses in the Battle of Magersfontein, with 39 men killed or taken prisoner in the Outpost fighting, while only 11 of the 52 men manning the outpost making it back to the main Boer defence lines. On 12 December, the Scandinavian Ambulance Unit found eighteen dead and two severely wounded on the battlefield. The wounded were the Finns, Sergeant Nils Viklund and volunteer Otto Backman. The other wounded had been collected by the British forces. Mr Uggla had sent Mr Hansen Stormoen from the Johannesburg Committee to assist the Company. Three graves were dug and the only remaining Company officer, Lieutenant-Quartermaster Claudelin, carried out the funerals.

Reorganisation after Magersfontein

Following the heavy losses sustained at Magersfontein on 11 December 1899, it was decided to dissolve the Company in favour of enabling the survivors to join a Boer commando. However, nothing had yet been done, when four days later, the news of another Boer victory was brought in, that of Colenso in Natal. The British advance had been halted and at Magersfontein there was a period of rest that lasted into February 1900. Meanwhile, Uggla had continued recruiting and on 20 January 1900, another twenty volunteers arrived from Pretoria under the command of Captain Jens Friis, a Dane. The decision to disband the Company was abandoned; instead, the unit would be reorganised as follows:

- Jens Friis (Denmark), Captain (Veldkornet)

- Helge Fagersk61d (Sweden), 1st Lieutenant

- Carl Magnus Lang (Sweden), 2nd Lieutenant

- Adolf Claudelin (Sweden), 1st Lieutenant-Quartermaster

- Gotthard Christensen (Denmark), Sergeant (Danish Troop)

- Johan Niklas Viklund (Finland), Sergeant (Finnish Troop)

- Norman Randers (Norway), Sergeant (Norwegian Troop)

- Charles Johansson (Sweden), Sergeant (Swedish Troop)

- John Rudolf Ruthstrom (Sweden), Corporal (Swedish Troop)

In February 1900 the British began advancing again, but instead of attacking the Magersfontein positions, they tried to outflank them. Late on 15 February, General Cronje began to evacuate the positions and move north. However, the Scandinavians’ horses were on a farm that was taken by the British before most of them had been collected. Thus, the Company had to travel by foot. During this period, three volunteers were lost. One was the Dane, Ludwig Rubech, who was wounded on 14 February and later died on 17 March 1900, although it is not known if he died from the wounds or from disease. On 15 February, Swedish Corporal John Rudolf Ruthstrom was killed near Jakobsdal and his fellow countryman, Wilhelm Stolze, was taken prisoner. On 16 February, at 06.00, the British Cavalry began harassing the column and the Scandinavians had to fight them off on several occasions before reaching Klipdrift, some ten kilometres west of Paardeberg.

Defeat and Capture at Paardeberg

During the night of 16/17 February, the Scandinavian company marched on, with Bloemfontein as their final destination. When daylight came, the troops put up camp at Wolwe Spruit. On the following day, 18 February, the British attacked, but the attack was repulsed. In this fight, the Swede, Elof Blombergson, and the Dutchman, Jacob Woolf, were killed. Two Finns, Sergeant Johan Viklund and volunteer Otto Backman, as well as Danish volunteer, Peter Krohn, were taken prisoner by the British. A serious blow was that the wagon carrying food and equipment was hit by a shell and burned out, leaving the Company with only a single spade for entrenchment.

Monday, 19 February, was described as the heaviest day of the fighting for the Scandinavians, despite there only being two wounded, the Swede, Oscar Cederstrom, and the Norwegian, Adolf Hansen, both of whom were taken prisoner a week later. On 20 February, the Norwegian, Abraham Abrahamsen, was wounded and taken prisoner by the British. After fighting for another week, General Cronje surrendered to the British at Paardeberg on 27 February 1900 and the Scandinavian company, then consisting of 47 men, marched into captivity.

What did the Boer War mean to Finland?

Those Finns who volunteered to fight in the Boer forces were, of course, immigrants to the Transvaal, people who had come to the gold fields of Witwatersrand in search of wealth and a better life. Some had arrived directly from Finland, others came via the United States. The uptick in immigration to the Transvaal had been one of the causes of the war, and the British guest-workers and settlers — the “uitlanders” — formed a fifth column through which the British Empire sought to strengthen its grip over the Boer republic. As a political and military strategy, the British attempt to control the Transvaal via migration failed utterly. After the outbreak of the war, most of the British immigrants were either deported or decided to leave on their own, rather than fight the Boer governments. Worse yet (from London’s perspective), the non-British immigrants — Germans, Dutch, Italians, Irish, Russians, and obviously Scandinavians, including Finns — decided to stay and support the Boer war effort. There is a further irony in the fact that most of the Finns in South Africa were Swedish-speaking, from coastal Ostrobothnia. This was an era of bitter language strife in Finland, when the rural Swedish population sought to present itself as a separate ethnic group of “Finland Swedes.” Nevertheless, the Finnish immigrants to South Africa identified closely with their former homeland, and set up a separate Finnish platoon rather than merging with the Swedish nationals who made up the majority of the Scandinavian Corps. Of the eighteen men who served in the Finnish platoon, only three spoke Finnish as their first language, but it appears that all of them regarded themselves as Finns. Matts Gustafsson, one of the volunteers who wrote poems, later noted, “Och wi voro finnar hwarendaste man,” which translates as, “And we were Finns, every single man.”

Although there was a lot of sympathy for the Boer cause outside of the British Commonwealth, there was little overt government support as few countries were willing to upset Britain, in fact no other government actively supported the Boer cause. There were, however, individuals who came from several countries as volunteers and who formed Foreign Volunteer Units. These volunteers primarily came from Europe, particularly Germany, Ireland, France, Holland and Poland. In the early stages of the war the majority of the foreign volunteers were obliged to join a Boer commando. Later they formed their own foreign legions with a high degree of independence, including the: Scandinavian Corps, Italian Legion, two Irish Brigades, German Corps, Dutch Corps, Legion of France, American Scouts and Russian Scouts.

While the vast majority of people involved from British Empire countries fought with the British Army, a few Australians fought on the Boer side as did a number of Irish, the most famous of these being Colonel Arthur Lynch, formerly of Ballarat, who raised the Second Irish Brigade. Lynch, charged with treason was sentenced to death, by the British, for his service with the Boers. After mass petitioning and intervention by King Edward VII he was released a year later and pardoned in 1907. However the free rein given to the foreign legions was eventually curtailed after Villebois-Mareuil and his small band of Frenchmen met with disaster at Boshof, and thereafter all the foreigners were placed under the direct command of General Koos De la Rey.

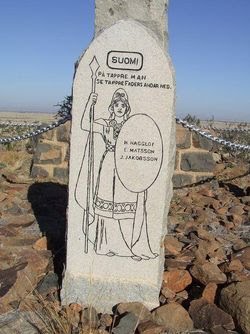

After the war, a special Scandinavian monument was constructed on the battlefield of Magersfontein. The monument consisted of four cornerstones, representing the four Nordic countries, each decorated with the Scandinavian valkyrie and national symbols of each country. The verse on the monument is from Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s March of the Pori Regiment, these days the official Finnish presidential march: “On valiant men the faces of their fathers smile.” The names of the fallen soldiers are engraved on the shield.

Emil Mattsson died at Magersfontein; he was buried on the battlefield. The British captured Henrik Hägglöf, who died from his wounds at an infirmary near the Orange River. Johan Jakob Johansson — whose name is mistakenly written “Jakobsson” — died at the British prison camp on St. Helena and is buried in grave number 18 at the Knollcombe cemetery on the island. The name of Matts Laggnäs, another Finnish volunteer who died in captivity on St. Helena, is missing.

The foreign volunteers who fought with the Boer forces — John MacBride perhaps being the most famous example — utilized their talents in later conflicts in their own homelands. The “flying columns” invented by the Boer commandos became a standard tactic in the Irish Republican Army. In Finland, the Boers served as an example to both the Civil Guards, who formed the White forces in the Civil War of 1918, and their Red Guard opponents. Lennart Lindgren, the commander of the Oulu Red Guard in 1918, was a veteran of the Boer War, and even Väinö Linna’s “Under the North Star” — something of a modern national epic in Finland, and recently made into a movie for the second time — includes a reference to Finnish Red Guardsmen “reminiscing about the stories of the Boers, which they had heard from their parents as small boys.”

What was the significance of the Finnish Republic’s 1924 commemoration of its citizens’ participation in the Boer War? Perhaps most importantly to Finland, the Boer resistance against the British Empire set an example for national movements of the time and this explains the Finnish fascination with the Boers. At the time of the war, the Grand-Duchy of Finland had become a target of Russian imperial reaction. The February Manifesto of 1899 began a Russian attempt to abrogate Finnish autonomous institutions and integrate it into the Russian Empire. The Boer resistance to Britain aroused sympathy in beleaguered Finland, oppressed by the Russian Empire, and the participation of the Finnish volunteers in the battle on the Boer side became a source of pride.

Arvid Neovius, one of the organizers of the underground opposition to Russia, wrote an article where he spoke of the “intellectual guerrilla warfare” and argued for modelling Finnish passive resistance to Russia on Boer hit-and-run-tactics. The South African Republic’s national anthem became a popular protest song that eventually found its way into Finnish schoolbooks. Finnish participation in another country’s war of national liberation was thus very much alive and supportive of the Afrikaner “liberation struggle” in 1924, only seven years after Finland gained its independence.

Finnish author Antero Manninen later described the view of the Boer War with the following words: “Over forty years ago, as the 19th century was drawing to a close, two small nations became targets of unjustified pressure and attack by their greater and more powerful neighbors. One of these was our own nation, whose special political status was singled out for elimination in the so-called February Manifesto; the other one were the Boers, living on the other side of the globe. This common experience between our nations was the reason why the people of Finland, like the entire civilized world, followed the Boers and their struggle for independence with special sympathy, and rejoiced for the successes they gained in the early stages of the war.”

The situation was paradoxical, because Russian popular opinion in 1899-1902 was also very sympathetic towards the Boers. Consequently, the Russian press could write with official state endorsement articles espousing a pro-Boer and anti-British postion …. while at the same time, the Russian Governor-General would censor similar articles in Finnish newspapers. During the inter-war era, the memory of the Boer War was invoked in Finland on many occasions. As mentioned, the old Transvall national anthem, “Kent gij dat volk” was translated in Finnish and included in elementary school songbooks.

The festivities of 1924 were followed by a Scandinavian shooting contest named “In Memory of Magersfontein” in Helsinki in the summer of 1925. A Finnish encyclopedia from 1938 contains a page-length article on the Finnish volunteers in South Africa, as a prologue to the history of the Finnish independence struggle. It was definitely considered an important historical event. The memory of the Boer War was also used in domestic Finnish political rhetoric. Perhaps the most famous example is Juho Kusti Paasikivi, who was the chairman of the conservative National Coalition party in the 1930s, and became the President of the Republic after WW2.

At the height of the extreme right-wing reaction and the activities of the Lapua movement, Paasikivi sought to actively distance the right-wing conservatives from the extremist elements and established himself as the right-wing champion of parliamentary democracy. On June 21st 1936 he traveled to the town of Lapua in Ostrobothnia, to the very cradle of Finnish right-wing extremism, and gave a speech entitled “Freedom”, in which he defended parliamentary democracy and civil liberties, urging the locals to abandon extreme right-wing radicalism. As a historical example to be followed, he invoked the memory of South Africa, and made a reference to a speech where Jan Smuts had also defended the parliamentary form of government: “As I was thinking of my presentation, I re-read one speech, made two years ago by a freedom fighter who, even though he lives and operates far away from our country, is a Western man by his opinions and character – the leading general and statesman of the Boer nation in South Africa, his name is Jan Smuts. As we all know, those Boer farmers, who served their God and fought for their freedom far away in the southern lands, share the same mentality as the people of Ostrobothnia…” The Union of South Africa was thus invoked as a model of democracy by the inter-war Finnish champions of democracy.

Finnish views were not however wholly one-sided in support of the Boers. At the time of the Boer War, the Finnish press did express some criticism towards the Boers. The one newspaper which stood out was the venerable Conservative-Fennoman Uusi Suometar (“New Finlandia” – , Suometar translates as the feminine embodiment of Finland), at the time the leading national newspaper with the widest circulation. Already during the autumn of 1899, Uusi Suometar adopted a critical tone towards President Krüger’s confrontational policy, and criticized the government of the Transvaal for a lack of realism. As far as is known, they were also the only Finnish newspaper which criticized the Boer actions towards the native African peoples in any way. The newspaper also expressed understanding for British interests, attempted to portray the war in a “fair and balanced” fashion, and expressed a hope that Britain would be willing to grant tolerable peace terms to the Boer republics.

This position was essentially a reflection of those same arguments which the newspaper advanced with regard to the question of Finnish autonomy and relations with Russia. As a conservative paper, the newspaper advocated Finnish acquiescence and compliance towards Russian imperial interests, in order to avoid excessive imperial reaction; while at the same time, they were also reluctant to criticize Britain, because they considered British goodwill and sympathy important in the international campaign for Finnish autonomy. (For details on the internation campaign on behalf of Finland, you may check the address “Pro Finlandia”, signed among others by Florence Nightingale, Émile Zola and Anatole France.

The year 1899 was an important year for many small nations, and Finland was a small cause célèbre for European intellectuals for a short period). Uusi Suometar was the largest newspaper, but it was probably an exception in its moderate approach to the conflict. Other Finnish newspapers were rather more openly pro-Boer. The constitutional Päivälehti (“Daily Newspaper”, a direct predecessor of today’s Helsingin Sanomat, “Helsinki News”) was very pro-Boer, although they also remembered to mention hat Britain should be considered as the “supporter and guardian of Finland in Europe”. Not surprisingly, this newspaper was also the favourite target of Russian censorship. The socialist Työmies (“Worker”), which was censored by both the Russian and Finnish authorities, was overtly pro-Boer, and regarded the conflict as an imperialist war initiated by the British capitalists.

Swedish-language Finnish newspapers were in a class of their own, because they were the only ones which mentioned the race factor openly. Nya Pressen, which advocated constitutional resistance towards Russia, condemned the British actions in South Africa precisely because of their nature as actions against another white nation. The newspaper made it specifically clear that they wholeheartedly approved colonial rule over “inferior” people, but the Boers were “representatives of European culture”. This was a clear reflection of the newspaper’s own view of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland as the “bulwark of Scandinavian civilization” standing against the Russian influence.

The other Scandinavian newspapers were equally divided in their opinions. The conservative Svenska Dagbladet was pro-British, but the liberal and social democratic Swedish newspapers were pro-Boer. The Norwegian Aftonbladet and Verdens Gang were pro-Boer, but also tried to avoid excessive criticism of Britain. The Norwegian reasons for this moderation were somewhat similar to Finnish motives; they were reluctant to jeopardize British support for Norway at a time when the termination of the union with Sweden was becoming topical. In their views, the Finnish newspapers were more or less part of the Scandinavian mainstream in their opinions and in their differences of opinion. The Russian opinion, however, was adamantly and absolutely pro-Boer and anti-British all across the political spectrum, from Tolstoy all the way to Lenin. As the war continued, even Uusi Suometar gradually adopted a more pro-Boer stance. The decisive factor in this change of opinion were the British actions towards the end of the war, the scorched-earth tactics and the concentration camps, which aroused absolute horror even in Finland.

The large scale deaths of Boer women and children in the British concentration camps evoked protests world-wide, as did the conditions in the island prisons of Ceylon and St. Helena, the latter of which housed Finnish prisoners for nineteen long months. The reason was simple. The British Empire was regarded as a liberal, responsible and humane great power, and if they could resort to such methods, what was going to prevent the other, more callous great powers from taking equally harsh actions with other small nations? Because of the Russian censorship, the Finnish newspapers could not openly mention that the British actions had ignited their fear of Russia, but the message was clear from between the lines. In 1924, these memories were still vivid in the minds of many Finns. The young people who lived in the inter-war era sang the Finnish translation of “Kent gij dat volk” in schools while in Church they would light a candle and recite the words “De God onzer voorvaden heeft ons heden een schitterende overwinning gegeven.”

Even after the successful gaining of independence from Russia, the clash between a few amateur Finnish riflemen and the professional soldiers of the British Army continued to hold a national symbolic importance in Finland. And in South Africa, the memories of Magersfontein linger on still in the heart of the Boer.

South Africa and the Winter War

By 1925, Finnish diplomatic representation in South Africa consisted of honorary consulates in five South African cities – Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban, Port Elizabeth and East London. The duties of the honorary consuls involved mainly trade and maritime affairs. Finnish nationals were preferred for the posts but when they were unavailable, Scandinavian nationals were somewhat reluctantly appointed. The Finnish foreign ministry held (understandably) suspicions that Scandinavians might promote exports from their home country rather than Finnish exports. The Great Depression of the 1930’s forced the intensification of cooperation between the Finnish foreign ministry and Finnish exporters in the search for new markets and South Africa became one of the targets.

From 1925 to 1939 exports to South Africa averages 1.45% pf the total value of Finnish exports annually. Although the figure is small, South Africa was a large market for Finnish sawn timber and was the number one source of imported timber for South Africa, ahead of both Canada and Sweden. Many of the Finnish firms which later achieved prominent positions in South African markets established their trading relationships at this time. Wool, tannic acids and fruits were in turn the top South African exports to Finland. However, even with the growing trade between the two countries it was not until 1937 that a Finnish consulate in Pretoria was actually established.

In the Winter War itself, there was little that South Africa could do to assist Finland. However, the South African Government donated 25 ex-RAF Gloster Gauntlet’s to Finland. These aircraft had been purchased to build up the South African Air Force but were still in Britain, not having yet been shipped to South Africa. Already obsolete, they were used as advanced trainers by the Finns. The Finnish nickname for the Gauntlet was Kotletti (literally “cutlet”). A Finnish Gloster Gauntlet Mk. II, OH-XGT / GT-400 is the only survivor of it’s type in the world and is preserved by the Lentotekniikan Kilta ( Air Force Technical Guild) during 1976-1982. You can see this historic aircraft for yourself at the Hallinportti Aviation Museum (located at Halli Airport in Kuorevesi, Jämsä, Finland

Below, a photo and a couple of videoclips of this historic aircraft, a reminder of old ties between Finland and South Africa.

Gloster Gauntlet GT-400 at Kymi 11th May 2011

Gloster Gauntlet GT-400 at Jämi in 2012.

Sources

- “Finns Abroad – a short history of Finnish emigration” by Olavi Koivukangas, Siirtolaisuusinstituutti – Migrationsinstitutet, Turku – Åbo 2003

- “Scandinavian Volunteers in the Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902” by Stellan Bojerud, Prof Mil Hist (Rtd), Royal General Staff College of the Armed Forces, Stockholm, Sweden

- An account of the activities of the Scandinavian Ambulance was written by Elin Lindblom in 1924 and is available online (Article by C de Jong, ‘Die verslag van suster Elin Lindblom oor de Skandinawiese ambulans in die Tweede AngloBoere-oorlog’ in The South African Military History Journal, Vol 4 No 5)

Appendix: Finns who served in the Scandinavian Corps

- Johansson, Jacob (Finland) – Wounded in Action, 25 October 1899, Mafikeng

- Mattsson, Emil (Finland) – Killed in Action, 11 December 1899, Magersfontein

- Backman, Otto (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 18 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Hagglof, Henrik (Finland), Wounded in Action, 11 December 1899, Magersfontein, prisoner of war, died of wounds 14 Dec 1899

- Michelson, Johan (Finland), Wounded in Action, 11 December 1899, Magersfontein, prisoner of war

- Viklund, Johan Niklas (Finland) Sergeant, Wounded in Action and made Prisoner of War, 18/19 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Bakman, Sunnion (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Erikson, Isak (Finland), Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg, died, St Helena

- Johansson, Jacob (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg, died, St Helena

- Johnson, Herman (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Johnsson, Erik (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Koehenen, Gabriel (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Kruts Gustavsson, Matts (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Nelson, Matts (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg, died on St Helena

- Nyman, Jan (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Rank, Johannes (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Schutz, John (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg

- Stenros, Karl Anders (Finland) – Prisoner of War, 27 February 1900, Paardeberg

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

6 Responses to Finns in the Boer War in South Africa – with the Boer’s