The Forestry Museum of Lapland (Lapin Metsämuseo) saves, researches, maintains and presents the cultural heritage of Lapland’s forestry history – and funnily enough, it’s the only museum in the world that concentrates on fostering the history of forest work in Finnish Lapland. It’s an outdoor museum located in the Pöykkölä part of Rovaniemi, about 3.5 kilometers from the city centre. Suiting the subject matter, the museum area is picturesque, located near water and in a countryside-like setting. There are currently 14 different buildings on the museum grounds, nine of which are museum buildings.

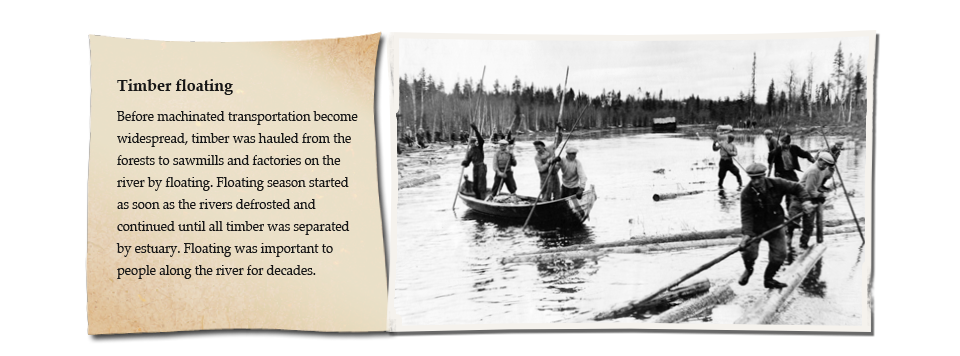

The Forestry Museum of Lapland tells the story of Lapland’s great logging era extending from the 1870’s all the way through to the machine operated forestry of the 1960’s-1970’s. In the picturesque wooded museum area there are genuine logging cabins, logging tools, timber floating tools and forestry machines on display. Forest cabins and other buildings (all of which can be entered) have been transferred to the museum’s location from various parts of Lapland and all the cabins, stables and saunas have their own interesting history. All the items on display also have their own story: one of the most interesting and impressive items on the museum grounds is the Sandberg steam locomotive that was perhaps the first of its kind used on machine operated logging sites in Finland (see the bottom of this post for a writeup on this unique and interesting piece of logging history).

Thousands and thousands of inhabitants received their daily bread from Lapland’s logging sites for nearly a century. What remains left from the era of tough manual work of the lumberjacks, the log floaters, the horsemen and the female camp cooks are now only stories, historic photographs, documents and the objects on display. The Forestry Museum of Lapland exists exclusively for telling these stories of a past rich in traditions and a unique culture that has now vanished.

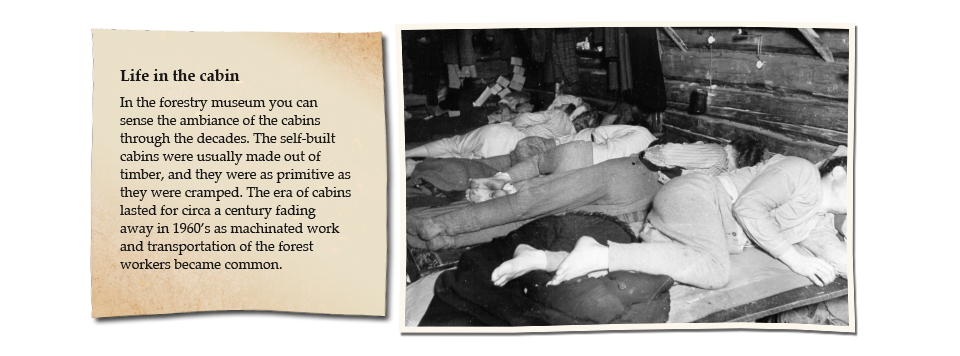

You can also see what life was like inside Logging Cabins. These were used by timber workers to live in at logging sites from the early days of logging in Lapland right up until the 1980’s. Cabins were constructed for the large logging sites where lumberjacks, horsemen, cooks and foremen stayed at the site for extended periods. The cabins were located tens of kilometres from the nearest villages and were often reached only on foot or by horses, something that kept the men at the cabins.

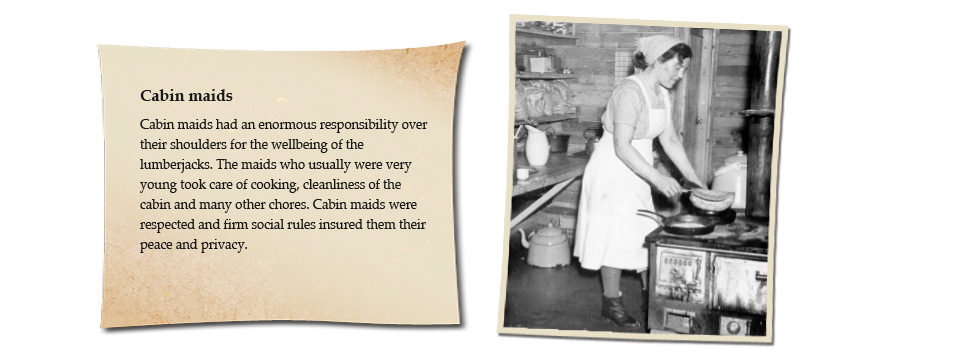

The cabins were moved from place to place when the work ran out and new worksites were established upstream. In order to receive provisions at the site, an agreement was made with a local shopkeeper who would deliver the goods to the wilderness. These “travelling tradesmen” sold the lumberjacks the provisions they required, such as tobacco, tools and clothing. Each cabin had its own cook who took care of preparing food for the workers. A maintenance fee was deducted from the workers’ salaries. With the decommissioning of the last logging sites at the end of the 1980s, efforts were made at the last minute to preserve these logging site traditions. In the Museum, you can see what it was like to live in these cabins.

And a Note: If you’re interested in staying in a Logging Cabin, the Municipality of Savukoski has a number of restored logging cabins for hire. They are excellent for using as a bases for excursions, camps and training courses. The Alatammi cabins are available for hire for 7 days at a time. The Kuusikko-oja cabin is only hired out for daytime use. The rental fees charged are mainly to cover maintenance costs. See the Savukoski Wilderness Travel website for more information.

Opening Days and Hours

The museum is open mainly during the summer season – from June 1st to August 31st, Tuesday–Sunday midday to 6pm (12–18). Closed on Mondays.

Entrance fees are 4 Euros (Adults), 2 Euros (Children 7-16 yrs, students and pensioners while children under 7 yrs are free. It’s good value for the money.

The Museum also offers Guided Tours around the museum (guided tours need to be booked in advance Tel. +358 40 53 600 80). Normal entry fees are applicable in addition to the guide fee. The maximum group size is 25 persons. The Museum website advises the Guided tour fee is: 25 € / group and the tour lasts one hour. If you’re really interested in the subject matter of the museum, that’s pretty good value for the additional information.

Location and How to Get There

The Forestry Museum of Lapland is easy to access if you’re visiting Lapland. The museum is situated in Rovaniemi, Finnish Lapland, circa 3.5 kilometers from the city centre towards the town of Ranua. The address is:

Forestry Museum of Lapland

Metsämuseontie 7

96460 Rovaniemi

Map showing location of Forestry Museum of Lapland

Forestry Museum of Lapland Website

A brief History of the Forestry Museum of Lapland

The Lapland Forestry Museum Association was founded in 1962 to preserve logging and timber floating culture and the long heritage of forestry work in Lapland. The museum itself was opened to the public in 1968 and has been regularly adding to its exhibitions and content. A lot of work by volunteers has gone into the Museum’s creation and upkeep.

A number of historic buildings and constructions have been moved onto the museum’s site since the 1960’s from different parts of Lapland. The oldest buildings date back to the early 20th century, the newest originate from 1950’s. A tour around the museum offers its visitors a vivid picture of logging and timber floating life through different time periods.

1960’s

In 1963 the transfer of the “Koivu bunk house” (built in 1904) started of construction on the museum site which lasted for two decades. During 1965-1966 in order to complete the log floating exhibition, a boathouse was erected. The steam ship “Uitto 6” was placed on the Salmijärvi shore in 1967. In 1968 the pontoon motor-wing boat “Uitto 33” was brought in to keep Uitto 6 company. In 1968 a smoke sauna originating from the 1940’s that had belonged to the Kemi Forestry Company was transferred to the site. In 1969 a bunk house which tells the story of life in timber camp bunk houses in the 20th century was erected.

1970’s

1970 was a significant year. Two buildings which the museum had received as donations were erected. One of them was a storehouse from the 1920’s that had operated on the logging site at Savukoski. The other one was a stable from the 1940’s. A canopy to protect the Sandberg steam locomotive and other forestry machines was also built. The same year a grandiose transfer operation to move the Luiro float cabin was started. This operation received significant help from the Finnish National Board of Forestry and the Veitsiluoto company. The erection of the building was a two-year undertaking, and would have not taken place without the involvement of forestry professionals and the help of local forest companies that were involved in the Forest Association’s activities.

1980’s

Construction work continued through 1970’s with the erection of two outdoor “forestry camp” lavatories that were for a long time in public use. In 1984 a storehouse was transferred onto the site and in 1986 the transfer of the Ahmakuusikko cabin from Hirvas was carried out. The latest museum building transferred to the museum site was a float storehouse that found its place near the float cabin in 1989.

Logging History in Lapland

Finland’s forestry industry is an important part of the country’s culture and history and forestry has an important role in Finland’s economy, both historically and now. Commercialization of forests began in Lapland when the first water sawmills were established at the end of 18th century. The operation of sawmills was, however, relatively small-scaled. From the early 19th century, growing demand for timber in Europe paved the way for the growth of the forestry industry in Finland. Forests in Southern and Central Finland had been logged and burnt over for centuries, which is why Lapland’s large, and at that time untouched, timber reserves attracted the interest of both domestic and foreign investors.

In 1860-1870 steam-powered sawmills were founded in various parts of Lapland near water ways. They generated plenty of work in logging and timber floating. In 1893 the first large timber company, Kemi Oy, was founded in Lapland. In the beginning, logging was concentrated in the Rovaniemi region but by the start of the 20th century the focus of logging had shifted towards the region of Kemijärvi. Gradually logging reached the municipals of Muonio, Kittilä, Sodankylä, Pelkosenniemi and Salla – eventually covering just about the whole Lapland.

Logging, timber floating and the sawmills offered work and income for thousands, work which resulted in growing prosperity of Lapland. With the income from forestry, magnificent houses were built, farming was improved, schools and libraries were founded. Rovaniemi, as the centre of the forestry industry and the home for the head offices of many timber companies, benefited even more than other areas from the booming economy and became a lively town. The number of inhabitants grew as many seeking work moved to the province from other areas of Finland.

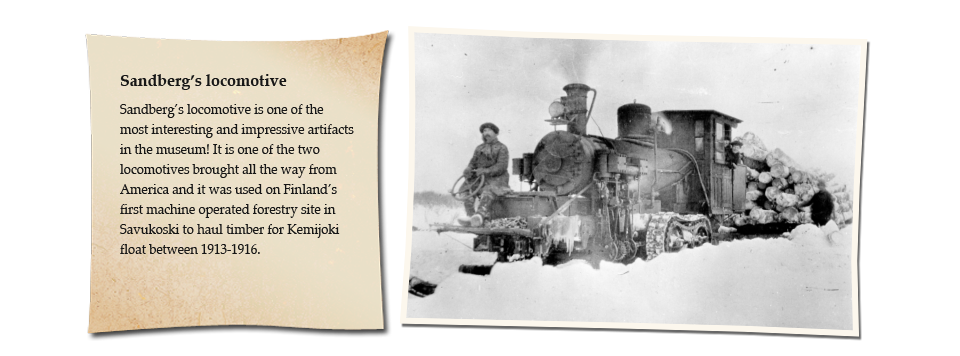

In Lapland there were many pioneering experiments and inventions carried out. Perhaps the most famous of them was the first attempt in Finland to haul timber with the aid of a machine in Savukoski between 1913-1916. As a remnant of this period, Hugo Richard Sandberg’s steam locomotive is on display at the Forestry Museum of Lapland.

The Sandberg Steam Locomotive

Logging was (and still is is) extremely tough and dangerous work. Even after all the technical developments of the last 100-plus years it still claims the lives of men at a frightening clip. One can only imagine the danger back at the turn of the last century. Of all the jobs, pulling the felled trees from the woods to staging areas where they could be transported to the sawmills was the most horrific. The logs were dragged out if the forest by teams of horses. In Finland, the secret behind the success and danger in this job was to move the logs in winter when the snow made movement easier. Snow could be packed down into ice roads, making a hard smooth surface over which sleighs loaded with logs could be moved easily.

Extraction of logs by horse and sledge. Snow and frost lowered the costs of extraction but it was hard manual work in freezing cold. There was a long tradition of using ice roads in Winter…

It was hard, dangerous and labour intensive. Logs were heavy, one slip could mean crushed or broken limbs. Runaway logs, logs that rolled off the load, logs that slipped from their harnesses, killed horses with regularity. The also maimed and killed the men driving the teams of animals. Conditions in the North American logging industry in the northern states and Canada were very similar to those in Finland, with all the same problems. And while steampower could be used in some areas, where logging railways were introduced, this was only really useful where the gradient of the land and the economics of logging in the area permitted the construction of railway tracks. There had to be a better way.

Thus the emergence of the steam-powered log hauler. The Lombard Steam Log Hauler was an invention that came from the mind of a talented Maine mechanic named Alvin Lombard. The Lombard Steam Log Hauler, patented 29 May 1901, was the first successful commercial application of a continuous track for vehicle propulsion (after Lombard began operations, Hornsby in England manufactured at least two full length “track steer” machines, and their patent was later purchased by Holt in 1913, allowing Holt, which later became Caterpillar, to be popularly known as the “inventor” of crawler tractors. Since the “tank” was a British concept it is more likely the Hornsby, which had been built and unsuccessfully pitched to their military, was the inspiration. In a patent dispute involving rival crawler builder Best, testimony was brought in from people including Lombard, that Holt had inspected a Lombard log hauler shipped out to a western state by people who would later build the Phoenix log hauler in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, under license from Lombard).

Legend has it that Alvin Lombard picked up the idea of “caterpillar” tracks from another budding inventor named Johnson Woodbury who had big plans, but no means to follow through. He passed his ideas on to Lombard who at the time had already come up with some commercially viable inventions and had the financial wherewithal to build this machine, assuming there was a demand. In a chance meeting of fate, Lombard happened to find himself sitting on a train next to a logging company executive (E.J, Lawrence, then president of a lumber company in Maine who envisioned a machine that could take the place of his numerous draft horses engaged in pulling felled trees out of the woods) who told him that his company would be first in line to buy such a machine, provided that it worked.

Lombard set to work immediately, drawing up plans and approached the Waterville Iron Works to actually construct the behemoth. He also filed for the patent on the machine. The date was November 9, 1900, and the construction of the prototype (named “Mary Anne”) was well underway. Work was completed just a couple weeks and it was on Thanksgiving day that the machine made its first public appearance. It was not all that impressive as the machine started shattering its tracks as soon as it transitioned from snow to hard ground. The problem turned out to be the grade of steel used. After some experimentation, they came up with a very durable steel that was tough enough for the job. The first Lombard machine had an upright boiler and an independent steam engine for each set of tracks. Turns were made by varying the speed of the engines, and with a team of horses hooked to the front of the beast to guide the front end around. This was quickly replaced by a set of front runners that were steered with a massive wheel. Mary Anne could pull 125 tons of logs at 4-5mph.

Lawrence immediately bought Mary Anne and ordered two more. Lombard set up shop in Waterville, Maine, and licensed the construction and assembly of the Logging Engine to other companies, among them the Phoenix Manufacturing Company of Eau Clair, Wisconsin; and Jenckes Machine Company Limited of Sherbrooke, Quebec. The upright boiler and multi-engines were replaced by a normal, locomotive-style lay-down boiler and single engine that used a differential to help vary the speed of the tracks. That power plant used was a railroad yard engine and this became the de-facto engine used to power the majority of the Lombard machines that were produced. The lay-down “saddleback” style boiler also placed more weight to the rear of the machine and increased its traction and hauling ability due to the fact that the water tanks were slung over the side of the main boiler body. In 1903 the first machine was sold to a logging company in Maine, and the orders began rolling in. The machines were shipped all over the country, with a total 83 built, most powered by steam, but a few of the later ones were powered by gasoline and the last was built to run on diesel in 1934, by which time trucks were becoming the normal mode of transport.

Because of the fact these were used in logging, many operators used wood to fire the boilers, and they used a lot. Warm weather dwellers may not be able to visualize 350 cords of wood, but that’s about the amount they would burn in order to pull 3 million board feet of wood, which sounds like a lot, but in comparison to the amount of fuel used, it isn’t. In fact, some of the companies had full teams of employees whose entire job was to supply the crawlers! The earliest haulers pulled three sleds while later models were designed to pull eight. The record train length was said to be 24 sleds with a total length of 1,650 feet (500 m).

The greatest operational difficulty was on downhill grades where ice allowed the sleds to accelerate faster than the engine. Jack-knifing sleds pushed many log haulers into trees, and most photos of log haulers show rebuilt cabs and bent ironwork on the boiler and saddle tank. Hay was spread over the downhill routes in an effort to increase friction under the sleds, but hungry deer sometimes consumed the hay before the train arrived.

The Lombard Steam Log Hauler needed a crew of four. The steersman sat on a platform at the front of the machine and was regarded as the hero of the crew, tasked with keeping the hauler on the track. Because the machine had no brakes and the only way to slow it was to reverse the engines, hills must have been scary as hell. He must have been working his wheel like a mad man. In sub-freezing temperatures down to 40 degrees below zero, he sat in an exposed position at the front of the engine. Sparks flying out of the boiler stack above him would sometimes set his clothing on fire while avoidance of trees required his full attention and effort turning the clumsy steering wheel. Some steersmen earned enough money to purchase fire-resistant leather clothing. Some log haulers had a small roofed shelter built on the steering platform, but the shelter limited the steersman’s ability to jump clear when collision became inevitable, and few steermen were able to avoid injury from the following trainload of logs when an accident happened.

In the cab at the back of the hauler were the engineer and fireman. The fireman shoveled coal, the engineer monitored the health of the engine while the striker was in charge of the while train of logs. A strikeman rode on the sleds with a bell-rope or wire to signal the crew in the cab (he would have been known as a brakeman on a normal train). To keep the engine running 24 hours a day, a second crew often traveled along in a caboose. The train could consist of up to 12 sleds full of logs if conditions warranted it. Each sled could hold up to 6,000 board feet of logs. Trips ranged anywhere from 3-5 miles if the logs were going from the forest to the river and up to 20 miles if they were going all the way to the mill. Speed was likely in the region of 4-5mph although they were known to reach speeds of up to 20mph when running downhill. Lombard also built a gasoline powered vehicle with wheels in front and Lombard crawlers in the rear – a half-track type vehicle.

Berlin Mills Company was one of the larger woods operators to use Lombard log haulers. They purchased one machine in 1904, and then purchased two more to maintain reliable operation when one needed repairs. The company maintained a single 6-mile-long (10 km) iced haul road in Stetson, Maine, by nightly application of water from a sprinkler sled, and strung a telephone line with frequent call boxes to dispatch sled trains over that road. The company estimated those three Lombard log haulers did the work of 60 horses.

In Wisconsin, the Phoenix Manufacturing Company of Eau Claire built these Lombard machines under license beginning in about 1904. Phoenix paid Lombard a $1000 royalty on each machine and built 175 of the machines. A Phoenix publication stated in 1910, “The Steam Log Hauling Locomotive, although only in use a short time, has proved a success beyond all expectations, making it possible to move 200,000 feet of logs every 24 hours while the same amount of money invested in horses would only move 50,000 feet in the same time.” The Phoenix Centiped as it was known (and one can surmise that this was where Holt, who had inspected a Lombard log hauler shipped out to Phoenix, may well have derived the “Caterpillar” name)was made to haul seven to eighteen heavily loaded logging sleighs over snow or ice roads. Each Centiped was outfitted with a set of skis on the front. The 100 horsepower four-cylinder engine operated at 200 pounds of steam per square inch. The log hauler burned either wood or coal–at least one and a half tons of good coal for a ten-hour trip. Water for the boiler was needed every four or five miles.

According to the March 5, 1908 edition of the Nor’West Farmer, the Sturgeon Lake Lumber Company introduced the Phoenix Centiped log hauler to its operations in 1905. The paper went on, “The Sturgeon Lumber Co. employs the unique train…in bringing lumber from its mill to Prince Albert, a distance of 30 miles. The engine is the only one of its kind in Canada, and its achievements are creating considerable interest among lumbermen. This engine was purchased in the early part of 1905 to do the work which had previously been done by mule teams…The winter of 1907 was the most severe in the history of the West. Despite these very adverse conditions, this engine did its work in a most satisfactory way. The usual load hauled for a distance of thirty miles between the mill and the city market is 150,000 feet.”

The Sturgeon Lake Lumber Company was pleased with the machine’s performance. Writing to the Phoenix Manufacturing Company in 1909, it reported, “Our engine has worked steadily this winter. It has been out all day, and sometimes all night in a temperature varying from 30 below to 55 below zero. We are at present hauling loads of 80,000 feet of green rough lumber a distance of 60 miles per day. There are some heavy grades upon the road which we find the engine climbs well. The regular train consists of seven loaded sleighs, a large tank of water, and a heavy caboose for the crews….We consider the engine is doing the work of 40 four-horse teams.”

In 1912, the Ladder Lake Lumber Company bought a Phoenix for use in its Big River area logging operations. It is not clear whether this was the same machine bought new by the Sturgeon Lumber Company in 1905. A few years later, The Pas Lumber Company bought out Ladder Lake and moved the Phoenix to the Pasquia Forest reserve east of Carrot River, Saskatchewan. We do not know how many steam-powered log haulers operated in Saskatchewan between 1905 and the early 1930s. It is thought that The Pas Lumber Company had at least six, two of which are now in the Western Development Museum collection. A total of eight Phoenix Centiped log haulers are known to have survived–two in Wisconsin, one in Iowa which came from Saskatchewan, one in Alaska and two in Finland.

Which brings us back to the Forestry Museum of Lapland and the “Sandberg” Locomotive – which is actually a Phoenix Log Hauler imported from Wisconsin. In 1913, the first of two locomotives were delivered to Finland via the harbor at Hankko (the second arrived in 1914). They were imported from the USA by Richard Hugo Sandberg (or “Samperi” as he was nicknamed) the influential and charismatic forestry manager of the Kemi Paper Company. The locomotives themselves were designed to run on coal, but were converted to run on wood as fuel for use in Finland. The locomotives were intended to be used to haul logs from the Nuorti logging site, near Tulppio in the Savukoski area, to the Kemijoki River from where the logs were floated down river during the spring floods.

The project was less successful than was hoped. It cost more than expected, and the high centre of gravity of the machines meant that they were easily toppled. Logging at Nuorti ended in 1916 due to the first world war. One locomotive is preserved at the Rovaniemi Metsämuseo (Forestry Museum of Lapland). The other is preserved at Tulppio. They’re well worth looking at as an interesting piece of technology and the ancestor of pretty much all of today’s caterpillar-tracked machinery.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Pingback: Finland's steam-powered Phoenix Log Hauler