Initial Steps towards a Finnish Maritime Industrial Complex

An important part of Finland’s economic growth through the 1920’s and 1930’s was her growing participation in the maritime trade internationally – both as a shipper and as an increasingly prominent participant in the maritime construction industry. This Chapter documents the initial steps towards a Finnish Maritime Industrial Complex. And an acknowledgement: substantial parts of this particular page are not original and were taken from a thread on www.alternatehistory.com by Jukra about Finnish maritime development. With Jukra’s permission, I’ve reused them for my own alternate history – a kindness that I gratefully acknowledge).

Finnish Maritime Construction – Background

By the late 1920’s, there were three major firms involved in the shipbuilding industry in existence in Finland – Crichton-Vulcan and Hietalahden Laivatelakka were shipbuilders, while Wärtsilä, an iron, steel and construction company, was the major manufacturer of marine diesel engines. Following independence and the drying up of the Russian market, the shipbuilders lacked any major construction contracts, hence there was major pressure on the government to place major shipbuilding contracts in order that the companies remain in business. As a result of the maritime legislation passed in the late 1920’s, the Finnish maritime construction industry expanded steadily, at the same time becoming increasingly innovative. Not only the large companies benefited. Starting from 1934, smaller shipyards were awarded ongoing contracts for the construction of high speed wooden torpedo and gunboats as well as large numbers of small Coastal Motor Torpedo Boats.

I – The Crichton-Vulcan shipyard

The Russian frigate Rurik (Рюрик) being launched in Turku, Finland in October 1851

Turku has a long tradition of ship-building, reaching back centuries into the past, with shipyards in one form or another having existed at the mouth of the Aurijoki River since at least 1732, with the first foundry and metal workshop established in 1842 as Cowie & Ericsson. Cowie & Ericsson built Finland’s first steam engine in 1850 and started to build steam ships in 1863.

Construction was of wooden ships until 1862, when William Crichton, a Scot, bought the Cowie & Ericsson workshop and built a new shipyard near the mouth of the Aura. Crichton began to build ships from iron and a join stock company was formed, merging in a number of smaller shipyards. In 1913 Crichton went bankrupt and a new company, Ab Crichton, was established in its place. During World War One, Crichton built ships for the Imperial Russian Navy, but with the Bolshevik Revolution, this work dried up and the shipyard faced hard times.

A smaller shipyard, Abo Mekaniska Verkstadt Ab was setup beside the Crichton Shipyard in 1874 and later, after merging with another shipyard, changed its name to Oy Vulcan Ab in 1899. Vulcan built a machine shop in St Petersburg in 1907 and prior to WW1, built marine engines which used heavy oil as a fuel. They also built pumps and steam engines. locomotives and a variety of military equipment – and owned two docks. By 1911, Vulcan employed 300 workers.

In 1924 the manager of Vulcan, Allan Staffans, organised a merger between the two companies, thus creating Crichton-Vulcan Oy. It was Allan Walfrid Staffans (13th February 1880 – 19th October 1946) who would be responsible for the success of Crichton-Vulcan and its growth into a major shipbuilder.

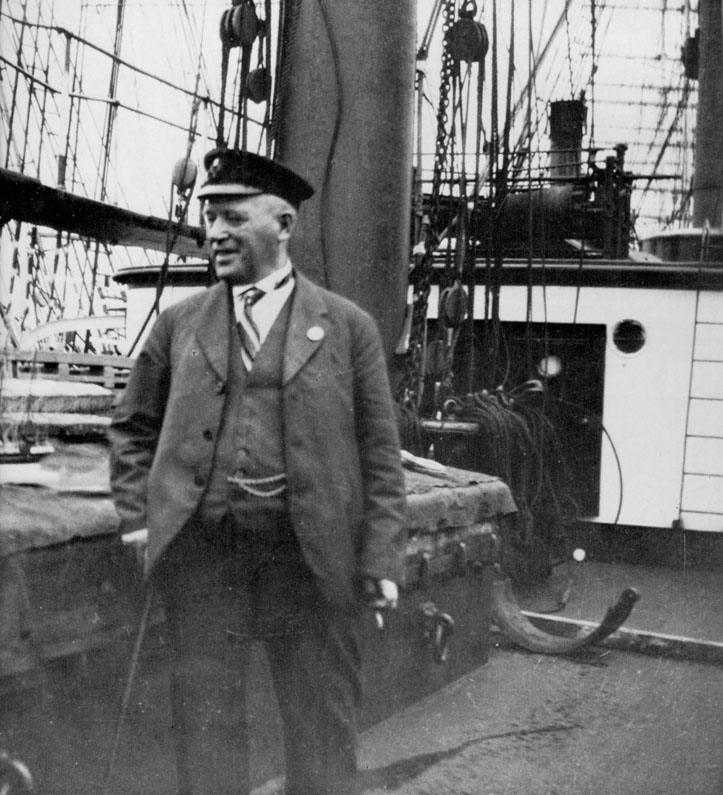

Allan Staffans (1880-1946), the manager of Crichton-Vulcan shipyard in Turku, Finland

Staffans was born in Vaasa, in what was then the Grand Duchy of Finland, attending school and graduating as a technician in mechanical engineering from the Vaasa Industry School in 1898. By the end of the 19th century the Vaasa shipbuilding industry, which once was a flourishing employer in the area, had almost disappeared. Staffans moved to Helsinki where he found a position at the Kone ja Silta shipyard, soon becoming a master of shipbuilding. In 1902 he was sent to work in Siberia, where he was placed in charge of building steam ships and dredging vessels built on the spot from materials transported from Finland. The parts were taken by rail to the Amur River delta and then built in place. The primary customer was the Imperial Russian Navy, which added the vessels to its Pacific fleet so as to enable shipping traffic on the large rivers. Staffans traveled to the Far East a total of six times, some of the journeys with his family. Staffans last trip to the Far East was via the Suez Canal and Indian Ocean, stopping in India, China and Japan.

Staffans planned to take leave for few years to study in Germany and the UK starting in 1914 but the outbreak of WW1 changed his plans. After Finnish independence, Staffans played a role in the Finnish Civil War, disarming the large guns of the Viapori Fortress outside Helsinki (whilst the Fortress was still occupied by the Russian military). Russia and Germany had agreed in the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty that the Russian Baltic fleet and coastal fortresses would not become involved in military operations in Finland. It also came out afterwards that the Russian soldiers were not very interested in the mutual skirmishes of the Finns. More information about the disputed event has been recently found in a report dated 26 March 1918 and written by Oskar Gros, who was a member of Staffans’s team. This document records that the work was done under the supervision of Staffans and with the consent of the Russian officers, who wanted to avoid operative cannon falling into the hands of either the Red Guards or German troops.

After the Civil War ended, Staffans remained in the Finnish Army and served in the Viapori Fortress from 1918 to 1920, where he held the position of technical manager of the dry dock. At the beginning of 1921, Staffans was appointed General Manager of the Vulcan Shipyard in Turku (he was selected manager because of his experience, high level of expertise and leadership skills). Vulcan had suffered heavy losses and was in serious financial trouble as orders from the Russian navy had ceased, some earlier deliveries had not been paid for and the company had lost its property in Saint Petersburg.

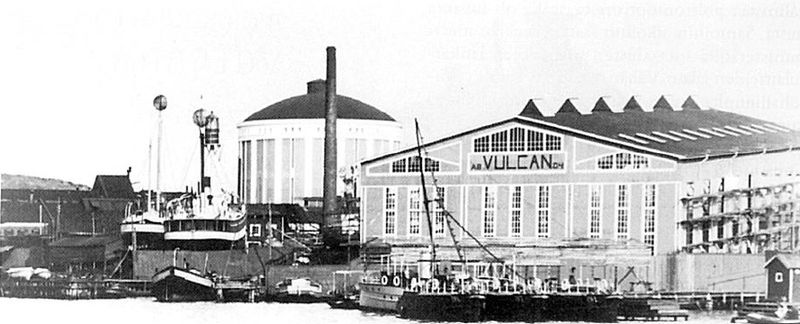

Aktiebolaget Vulcan shipyard in Turku, Finland. Lighthouse ship Storbotten (sunken 1922) docked on the left. Gasometer in the background

In 1922 Staffans negotiated with the Finnish Government to repair an old Russian submarine. As the company had no experience with submarines, Staffans searched for contacts with the necessary knowledge and technology. Although the project turned out to be hopeless, Staffans managed to establish a relationship with the Dutch company IvS, which was eager to start a submarine project with Vulcan. IvS was a German dummy company set up to maintain and develop German submarine engineering expertise, when it was not permitted to do under the impositions resulting from its defeat in WW1. During 1922–1923, Staffans attended Finnish naval defence strategy planning committee meetings. Vulcan and IvS signed a secret contract about co-operation for submarine engineering in November 1923. Under the contract, IvS committed to provide all the needed engineering support in case Vulcan won any contracts to build submarines. In the following month Staffans negotiated about a merger with Crichton.

Finnish Navy Grom-class Destroyer being built in the Crichton-Vulcan yards, late-1940

The merger of Crichton and Vulcan took place in 18 August 1924 and Staffans was chosen unanimously to lead the new, united Crichton-Vulcan yard. The yard had only few orders underway and Staffans hung his hopes on getting orders from the Finnish Navy. As a result of the Maritime Construction Program, Crichton-Vulcan would prove to be one of two major shipbuilding beneficiaries of the Finnish Government’s support for the development of the Maritime Industry, constructing icebreakers, submarines, naval warships and merchant ships.

Building of such large and demanding ships required investment in facilities and cranes; also the number of employees was substantially increased and under Staffans’ leadership, Crichton-Vulcan grew into its position as the strongest and most modern shipyard in Finland. During the 1930’s Crichton-Vulcan also managed to sell ships to the Soviet Union. Staffans’ excellent Russian language skills proved helpful in the negotiations, and contracts for a total of 29 ships were signed with the Soviet Union; the orders were vital in the middle of the depression. As the yards reputation grew, Crichton-Vulcan received more demanding and challenging orders through the last half of the 1930’s; in addition to the naval and Soviet orders, a total of 17 large merchant ships were ordered between January 1936 and September 1939. Staffans’ right hand in this work was the company’s main engineer Gösta Rusko, who was also Staffans’ son-in-law.

The expanding construction work required continuing investment in cranes, building platforms and workshops – expansion which was financed by the ongoing orders received and through sales of shares on occasion (Wärtsilä would eventually come to own 98% of Crichton-Vulcan as a result of these share sales, and would eventually come to take over Crichton-Vulcan completely). The expanding work also required skilled and professional shipyard and metal workers and many were recruited from Central Europe, moving to Finland with their families through the 1930’s.

Despite the souring relationship with Germany after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and soon, the Winter War, Crichton-Vulcan would also continue to do business with Germany, delivering of the ships to the German Kriegsmarine as well as signing contracts to build cargo ships for Germany. A total of 38 vessels were handed over to Germany before Finland went to war with Germany in April 1944. After the Winter War, the Soviet Union would again become a customer of Crichton-Vulcan’s, signing an initial contract for four tugboats with the Soviet Machinoimport. This was soon followed by a contract for 12 more slightly larger vessels of the same kind. In addition, Crichton-Vulcan would continue to build naval warships for the Finnish Navy through the war years, primarily the Finnish Navy’s Grom-class Destroyers but also anti-submarine corvettes and submarines. Over WW2, Crichton-Vulcan would employ more than 3,000 shipyard workers.

II – Hietalahden Laivatelakka shipyard

The Hietalahden Laivatelakka shipyard in Helsinki was founded in 1865 by Adolf Törngren and was located at Helsinki Skeppsdocka. The company went bankrupt in 1894 , after which it continued operation as Hietalahden Laivatelakka Shipyard and Engineering. In 1904 , the company received a substantial order from the Russian Ministry of Marine for steam-powered torpedo boats. In 1910, the first Finnish-built icebreaker, “Mercator”, was built in the Hietalahden Laivatelakka shipyard (by 2012, Helsinki shipyards would go on to deliver approximately 60% of the icebreakers in operation around the world).

As with Crichton-Vulcan, WW1 saw demand from the Russian Imperial Navy grow, but again, the Bolshevik Revolution led to the disappearance of these orders and hard times for the company. In 1926 Machine and Bridge Construction acquired the entire share capital for 8.6 million Finnish Markka. In 1928, Crichton-Vulcan acquired ownership but continued to operate as an independent business.

Hietalahden Laivatelakka became the second major beneficiary of the Finnish Government’s support for the development of the Maritime Industry, constructing icebreakers, naval warships and merchant ships. Hietalahden Laivatelakka did not build submarines. In 1938, Wärtsilä acquired Hietalahden Laivatelakka, as a result of which Wärtsilä became the largest shipbuilding and engineering group in Finland (the Hietalahden Laivatelakka shipyward continues to operate today as Arctechin, with the shipyard operating adjacent to the residential areas of Jätkäsaari and Hernesaari).

III – Wärtsilä

Founded in 1834, Wärtsilä was established when the governor of the county of Karelia approved the construction of a sawmill in the municipality of Tohmajärvi. In 1851, the Wärtsilä ironworks was constructed. In 1898, ownership of both the sawmill and the ironworks changed hands, being renamed Wärtsilä Ab, then becoming Ab Wärtsilä Oy in 1907. In 1908, the Saario rapids power station started operating and Wärtsilä became a modern smelting plant and steel mill running on electricity generated from the power station.

Wärtsilä was a major beneficiary of the government’s economic policies. In the late 1920’s a galvanization factory manufacturing magnetically galvanized wire was completed. In 1929, Wärtsilä acquired a majority holding in Kone-ja Siltarakennus Oy (Machine and Bridge Construction Ltd), a company which manufactured machinery for the paper industry machinery. Wärtsilä’s headquarters move from Karelia to Helsinki. In 1930, Wärtsilä acquired the Onkilahti engineering workshop in Vaasa and in 1931, the Pietarsaari workshop in Pietarsaari. In 1932, the Kone-ja Siltarakennus Oy group was merged into Wärtsilä, along with the just acquired Taalintehdas Steel Mill (est’d 1686) and the Turku, Pietarsaari and Vaasa subsidiaries.Wärtsilä-Yhtymä O/Y (Wärtsilä Group Ltd) was established under chief executive Wilhelm Wahlforss.

In 1927, Wärtsilä signed a licence agreement with Friedrich Krupp Germania Werft AG in Germany to manufacture diesel marine engines. The first Finnish-constructed marine diesel engine saw the light of day in Turku in November 1929. Wärtsilä went on to become the major manufacturer of marine diesel engines for the Finnish shipbuilding industry, supplying all the marine diesels used in the construction of the Finnish icebreakers, merchant marine and the Finnish naval construction programs. Through its acquisitions of Finnish shipyards, Wärtsilä would also go on to become a major shipbuilder.

Development of the Finnish Maritime Shipping Industry

I – The Icebreakers

The history of winter navigation in Finland dates back to the 17th century when mail was carried year-round between Turku, Finland and Grisslehamn, Sweden, over the Sea of Åland. During winter, ice boats were used to carry the mails. These were specially strengthened sleigh-boats that were pushed over the ice until it broke under the weight of the boat. Once the boat was in the water, the crew began rocking the boat back and forth until it broke the ice, they continued to do this until they reached open water. This mail route was often called the most dangerous in Europe.

The Danish icebreaker Bryderen

In the 1860’s there were plans to start year-round traffic from the Hanko, the southernmost tip of the continental Finland, but even the Finnish Pilot and Lighthouse Authority was doubtful about the proposals – the director’s aide was quoted as saying that this close to the 60th parallel north, winter traffic from Hanko would forever be a distant dream. Despite opposition, a harbour and railway connection were built in 1872–73. Several domestic and foreign shipping companies attempted year-round traffic with varying commercial success, but the port of Hanko remained closed for several months nearly every year.

In early 1889, Finnish factory owners eager to export year-round encouraged the Danish shipping company Det Forenede Dampskibs-Selskab to send their icebreaker, Bryderen, to the northern Baltic Sea and try to open a path to the icebound port of Hanko. Bryderen, the most powerful icebreaker in Europe at that time, had a 1,000 ihp (750 kW) steam engine and could easily break ice up to 45 centimetres (18 in) thick. The Senate of Finland became interested in the experiment as its result would prove ot disprove the viability of winter navigation. In April 1889 the Bryderen and the Vesuv, a small cargo steamer also owned by the Danish shipping company, approached Hanko through the ice-field, with the icebreaker creating a channel down which the cargo ship followed. Large headlines in the major Finnish newspapers reported how the ice blockade had finally been broken – a foreign icebreaker had come through the ice and was now moored at a Finnish port. The successful arrival of Bryderen was also seen as the answer to the question whether or not an icebreaker would be needed in Finland.

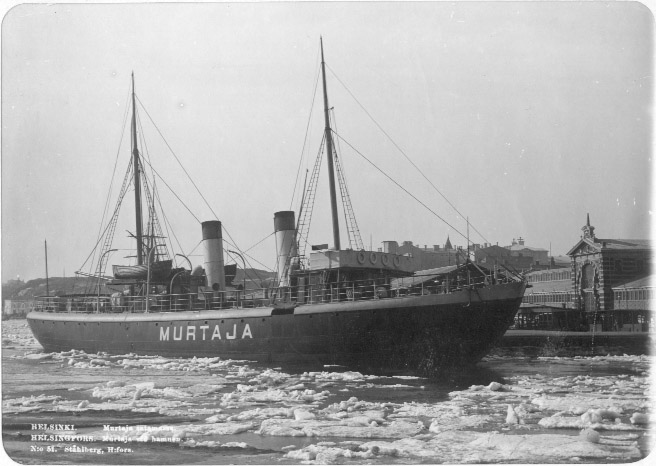

Icebreaker Murtaja in the port of Helsinki in the 1890s

Shortly after, the Senate requested bids for a steam-powered icebreaker capable of breaking a 32-foot (9.8 m) channel. A Swedish design was approved and the Murtaja (“Icebreaker”) was launched in 1889. She was the largest and most powerful icebreaker in service at the time. However once in operation, Murtaja proved to have an inefficient hull form, meaning that at times the crew had to rely on hacking and sawing the ice or using explosives. She could not keep the port of Hanko open every winter and the Senate came to the conclusion that a second icebreaker would be needed. The new icebreaker, equipped with propellers at both the bow and stern, was built in 1898 and given the name Sampo.

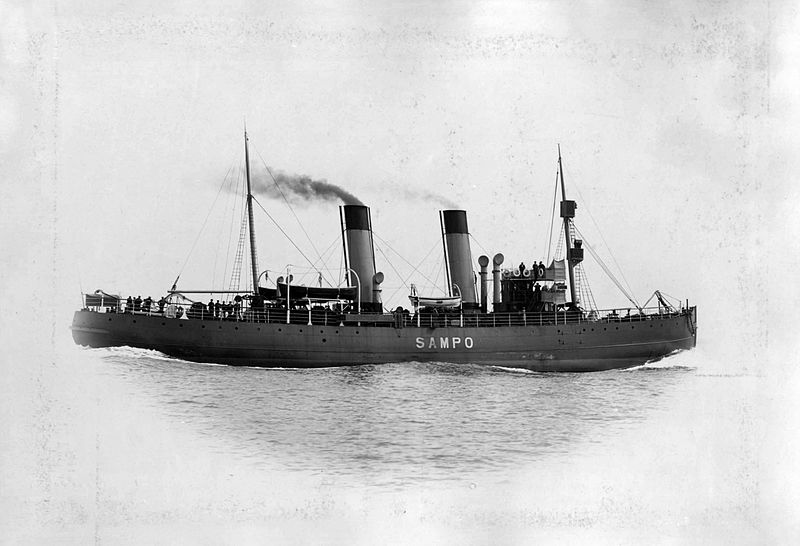

Finnish icebreaker Sampo, built 1898 and scrapped in 1960, undergoing sea trials.

Sampo was based on a US design developed in the 1880’s and was built by British shipbuilders Whitworth & Co Ltd from Newcastle upon Tyne. While not the cheapest, the shipyard had the shortest delivery time — only seven months — for an icebreaker with bow propellers. Sampo entered service in 1898 and was capable of breaking through ridges up to six metres thick by ramming, performed beyond expectations and was generally deemed the best icebreaker in Europe at that time. In 1907, another icebreaker with a bow propeller, Tarmo, was ordered from the builders of Sampo (Tarmo, incidentally, is preserved at the Maritime Museum of Finland, in Kotka. She was completely restored in the 1990’s).

The number of merchant ships calling at Finnish ports and requiring icebreaker assistance during the winter months had increased steadily since the first Finnish state-owned icebreakers, Murtaja and Sampo, were built in the 1890’s. In 1902 General Nikolai Sjöman, the director of the Finnish Pilot and Lighthouse Authority, made a proposal to the Senate of Finland for the construction of the third state-owned icebreaker. In 1906 the Senate announced that the Murtaja would be replaced and called for bids. Once again, the bid from Armstrong Whitworth was accepted and the new icebreaker was launched on 9 September 1907 and given the name Tarmo (“vigour” or “spirit”). When the icebreaking capability of the Tarmo could finally be assessed, it was found out that the new ship was not as maneuverable as the smaller and less powerful Sampo, and the changes made to the original design did not improve her performance.

Finnish icebreaker Tarmo at the Kotka Maritime Museum in 2006

However, despite the shortcomings Tarmo was still a valuable addition to the state-owned icebreaker fleet, and after a number of changes her icebreaking characteristics were on a par with Sampo. During the 1910s, Tarmo assisted ships to the port of Helsinki and moved to Hanko with Sampo after the New Year. As the spring approached, she was sent first to the Gulf of Bothnia and finally to the eastern part of the Gulf of Finlandto open the ports for the spring. However, during the winter months the icebreakers were not sent beyond Vaasa. In August 1914 WW1 broke out and the Baltic Sea became dangerous due to naval mines and German U-boats. The Finnish icebreakers were placed under the command of the Imperial Russian Navy’s Baltic Fleet and were assigned to assisting naval ships and troop transports in the Gulf of Finland. Despite the harsh winters, icebreaker assistance to merchant vessels was largely neglected, and several ships were destroyed by ice

When independence was declared, the Finnish-state owned icebreakers raised the Finnish flag. When the Civil War broke out, Tarmo was captured from the Russians (who had guards on the ship) and was used to transport Senators Pehr Evind Svinhufvud, the future President of Finland, and Jalmar Castrén to Tarmo disguised as engineers. They were taken to Tallinn and Tarmo would go onto transport Finnish and German soldiers to the island of Suursaari. In early 1919 she was used for transporting volunteers to Tallinn to aid in the Estonian War of Independence. She also transported Mannerheim to Stockholm and Copenhagen in February 1919.

In May 1918, the Finns had acquired a fourth icebreaker. This was the Silatch, built in 1910 by the Crichton yard in St Petersburg. Silitch had secretly sailed to Kotka to evacuate remaining Red Guards but was seized by the Finns and joined the Finnish icebreaker fleet as Ilmarinen. She was returned to the Soviet Union under the terms of the Treaty of Tartu, but in return, the Soviets returned the Finnish icebreaker Apu.

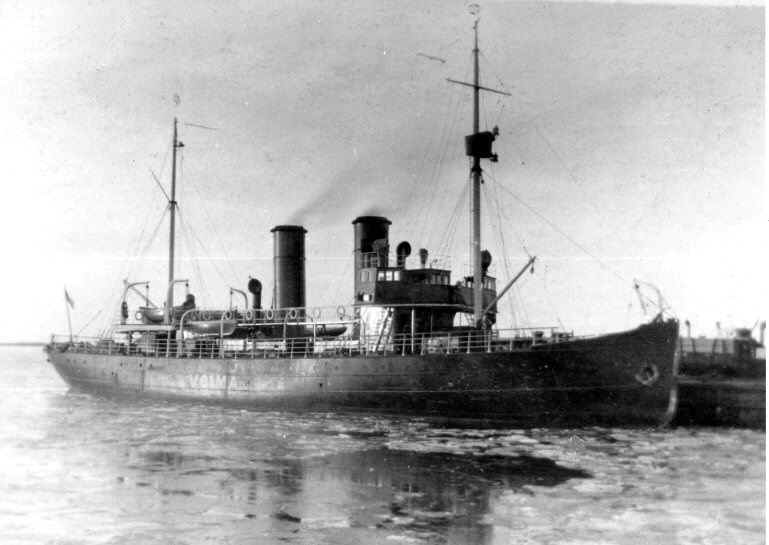

Finnish Icebreaker Apu, originally built as Avance in 1899

Apu had been built in 1899 and was initially owned by a private shipping company founded by shipowners from the Finnish city of Turku and known as Avance. Her main task was to assist ships between Turku and Stockholm, although she was found to be suitable for icebreaking in the sheltered waters within the archipelago, a task to which she returned after independence. In many ways Apu resembled the first state-owned icebreaker of Finland, Murtaja, although her bow was of improved Swedish design which increased her icebreaking capability. The angle of the stem, the first part of the ship to encounter and break the ice, was 22 degrees. Still, she was of the same outdated European design as Murtaja and thus had similar problems in difficult ice conditions. Her coal stores were also located too far in the front, resulting in an unfavorable trim at full load.

Fifth of the Finnish icebreakers was Voima. She was being built at Werft Becker & Co. in Tallinn in 1916, was captured by the Germans and taken to Danzig where she was fitted with engines in 1918. After the war she was bought by the Finnish shipowner John Nurminen, who had her towed to Helsinki. When Nurminen began offering her to the state of Finland, he faced severe opposition even though he offered to accept the old and, to some people, outdated icebreaker Murtaja as part of the payment. Her rusted hull was seen as a pile of scrap, not worth the government’s scarce funds, and she didn’t even have a bow propeller which was seen as a crucial component of a modern icebreaker. However, several maritime professionals saw her potential and the owner of Götaverken, Hugo Hammar, even said that once finished, Hansa would outperform the largest icebreakers of Finland at that time, Sampo and Tarmo.

Finnish icebreaker Voima, finally completed in 1924

The rebuilding was awarded to Sandvikens Skeppsdocka och Mekaniska Verkstads Ab in Helsinki and the work began in late spring 1923. During the ten months the icebreaker spent in the shipyard she received a new bow with a bow propeller and two German steam engines with an official combined maximum output of 4,100 indicated horsepower (3,100 kW), making her the most powerful Finnish icebreaker at that time. On 15 December 1923 she was given the name Voima, meaning “power” in Finnish, and during the first sea trials on 6 March 1924 she turned out to be an excellent icebreaker that left a broad ice-free channel behind her. Voima had also cost considerably less than a new icebreaker with similar characteristics and performance.

The sixth icebreaker to enter service was the Jääkarhu (“Polar Bear”). She was Built in 1926 by P. Smit Jr. Shipbuilding and Machine Factory in Rotterdam, Netherlands, and was the last and largest steam-powered state-owned icebreaker of Finland. The driver for her construction was both the increasing size of the ships calling at the Finnish winter ports and the increasing amount of exports, especially forest products, which had increased considerably since WW1. There was a definite need for a large and powerful icebreaker. One of the key issues was the beam of the existing icebreakers, 14 metres (46 ft), which was not enough for the new ships used to transport goods across the Atlantic Ocean. The basic design of the new vessel, which was to have a beam of at least 18 metres (59 ft), was awarded to experienced Finnish naval architects K. Albin Johansson and Ossian Tybeck.

In the end, the contract was awarded to the Dutch shipbuilder P. Smit Jr. Shipbuilding and Machine Factory from Rotterdam. The shipyard had recently constructed four ice-strengthened ships for the Finland Steamship Company and the technical director of the company had personally spent several weeks on board the Finnish icebreaker Sampo during the previous winter. She entered service in 1926 and, Although sometimes called the largest and most powerful icebreaker in the world by the press in the 1920’s, Jääkarhu was no match for the Soviet polar icebreakers Yermak and Svyatogor. These Soviet icebreakers had nearly twice the displacement and over twice the power of the Finnish icebreaker. However, as a Baltic escort icebreaker she was considered better than the giants and was often compared with the Soviet icebreaker Lenin, which was roughly of the same size and was considered a very successful design.

Jääkarhu arriving in Helsinki in April 1926.

Thus, in 1927, the Finnish icebreaker fleet was based on six icebreakers with a total power of 23 000 horsepower. The five older ships all were coal-fired and lacking range for continuous operations. The oldest, Murtaja, was of 1890 vintage and lacked even a keel propeller. The newest one, Jääkarhu, was the darling of the fleet. With a breadth of 19.3 meters, 9200 horsepower and tilt tanks she was a powerful addition to the icebreaker fleet and could single-handedly aid ocean going liners and tankers in and out of Finnish winter ports. Her triple-expansion steam engines were oil-fired, providing far greater endurance than with the older generation of coal-fired icebreakers. Even though the Soviet icebreaker Krasin was even more powerful, Jääkarhu was clearly among the best icebreakers in the world.

However, in some respects the Jääkarhu was already obsolete. Diesel electric propulsion, to be introduced to the Finnish Navy in submarines, provided the capability to direct power easily to pumps, keel or stern propellers or whatever else was the need and also allowed for greater endurance and more economical operations. This was clearly the way of the future. Bubble shrouding of the hull was also lacking. The Swedes were already considering diesel-electric propulsion for their “Statsisbrytaren II”, to be named Ymer.

The “Karhu” Class icebreakers – here the first of the class being finished at Hietalahden telakka yard, Helsinki

The Finnish Maritime Authority foresaw a need for two separate classes of ice-breakers. First would be an 8,000 horsepower, 4000 ton class of 14 meters beam to be used to keep sea lanes in the Gulf of Bothnia open for large transoceanic cargo ships, the “Karhu” class. Projected performance was to be 15kts in open waters and 6-8kts in 50 centimeter ice with a maximum capability of 120cm of solid ice. The projected names for the class would be Karhu, Otso, Kontio and Mesikämmen, all synonyms for bear, the traditional “King of the Forest” in Finnish folk mythology. The second class was to be even more ambitious. The Sisu class was to be of 6000 tons and 10,500 horsepower with 19.5 meters beam and was to be used to assist shipping for Kotka, Viipuri and Helsinki, keeping the routes open for large ocean-going tankers and liners. The first ship of four in the Sisu Class was to be delivered in 1932, with one a year coming into service thereafter.

Inspired by the use of icebreakers in the Civil War and the First World War, the new icebreaker classes were designed from the outset to be armed if deemed necessary. The armament for both the “Karhu” class and “Sisu” was to be four 4″/60 1911 pattern guns, four 40mm Bofors guns and depth charge racks.The projected wartime role for the icebreakers in the summer season was to be convoy escorts. Additionally, the icebreaker “Karhu” was to be designed to be used as a tender for the Navy’s submarines.

Orders for four Karhu Class icebreakers were placed in 1928, the ships were scheduled to be delivered between 1930-1931. The order was allocated to Hietalahden Laivatelakka (Crichton-Vulcan would receive other orders from the Government).

II – The establishment and initial operations of Merivienti Oy – 1928-1932

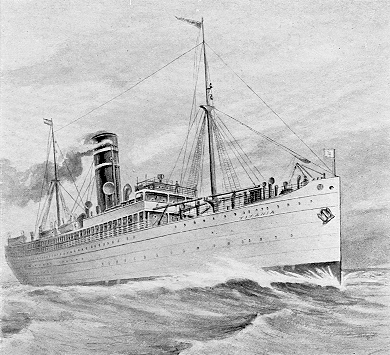

Maritime Shipping was to be organized under two business arms – the Finnish North American Line (SPAL) and the Finnish South American Line (SEAL). For SPAL operations, a hodge podge of ten pre-WW1 cargo ships were bought to start up the initial operation, operating a once in a week service to North America, initially to Boston, New York and Baltimore.

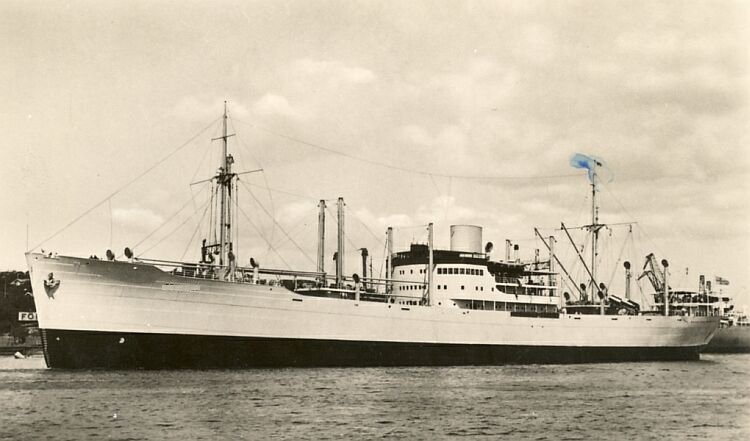

Hog Islander “Finntrader” of SEAL approaching Kotka in June 1929.

For SEAL, there was a need for faster and larger ships and the decision was made to purchase a uniform class of twelve fast cargo ships. The ships decided on were Hog Islanders, constructed en masse to replace the Allied shipping losses during the First World War for the Emergency Fleet Corporation of the US Shipping Board. The ships operated a two weekly service between Finland, Brazil and Argentine. Hog Islanders were fast and, from the Finnish perspective, quite large ships. Although the ships were almost ten years old, their method of their construction was studied carefully by Finnish firms as further orders for a uniform class of ocean cargo ships was expected within a short timeframe. Hog Islanders proved expensive to operate as they used manpower intensive steam turbines which had the effect of further directing the Finnish marine engine development effort towards the use of diesel and diesel-electric propulsion. Hog Islanders were of 5000brt, 8000dwt and had an operating speed of 15kts. SEAL ships did not gain their white livery until the late 1930’s – when white was introduced to promote the cleanliness of Diesel propulsion

The initial operations of Merivienti were unprofitable for a number of reasons. Cargo operations started at the beginning of 1929, just as the Great Depression was about to shake Finnish export markets and seriously disrupt the whole international trade system. The Ships were purchased just before the international slump for what were high prices. The purchase of the expensive and expensive to operate Hog Islanders was heavily criticized, but in fact the goodwill gained was important later on when neutralization of the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs became essential. Another element was the hostility of cargo shipping cartels in which the established shipping lines shut out the new state-funded competitors until 1930, when the solidarity of shipping lines evaporated under the pressures of the Great Depression. Finally, while Finnish forestry companies had operated the Finnpap export association to promote Finnish forestry products successfully in the United States and Britain since 1918, other Finnish industries did not follow suit very effectively until state funds were allocated and state guidance provided to address the issue and assist them.

The alleged corruption and seemingly overambitious plans gained political attention, especially from the far left and, somewhat surprisingly, also from the far right. For the far left, as mentioned before, Finnish plans to strengthen export industries were a threat to similar Soviet efforts. Moreover, any measure strengthening capitalist Finland was seen as a threat to the Soviet Union. For the far right, the so called Lapua Movement (Lapuan Liike) also criticized the maritime infrastructure program. This was due to the implied threat of factories, ports and high technology to the traditional agrarian lifestyle that the Lapua Movement would have preferred for Finland.

Hostility towards business interests was one of the factors which resulted in the Lapua Movement losing popularity with the Finnish electorate and this resulted in the movement being outplayed in the political field even before it’s total crash after the 1932 coup attempt. The coup attempt was not the beginning of a new era of political instability, but rather end of the instability. After threats from both the left and the right ends of the political spectrum had been effectively defeated, the unprecedented economic boom which ended the Finnish Great Depression earlier than in most countries (just as in OTL) was a powerful antidote to extremist idiocies which were gaining power all over the world. Unfortunately for Finland and other democratic countries the domestic threats for democracy were not the only threats that existed, as was seen during the late 1930’s.

III – The Icebreaker Sisu in service between 1932-1939

While the initial plans for the “Sisu” were rather traditional, the new “Super-Icebreaker” created large-scale public interest and thus in addition to having the most modern technology incorporated, the ship was also to have sleek modern lines, as can be seen in the photograph. One might make a good argument that the modern design was a symbol of Finnish modernization, creating a break from the past, just as various Finnish public buildings of the era were spectacular examples of functionalist architecture.

Icebreaker “Sisu” in a 1939 promotional picture. The antenna in the foremast is not a radar but an experimental direction-finding antenna

Public interest in the project created an another requirement: “Sisu” was already designed to be among the most powerful icebreakers in the world. As a result of public interest and in response to the nationalism that was inspired by the ship, the specifications were rewritten for “Sisu” to become the most powerful icebreaker in the world, ahead of Soviet “Krasin”. Ultimately, in terms of engine power the “Sisu” was surpassed by the Soviet nuclear icebreaker “Lenin” in 1959. However the post-war Finnish, Swedish and Soviet icebreakers of the “Voima”-class were more powerful in terms of icebreaking capacity due to improvements in design. The diesel-electric machinery of “Sisu” was a challenge for Finnish industry, but it was a challenge the meeting of which proved to be useful as the demand for electrical machinery grew significantly in the 1930’s for both domestic and export use.

Thus the final specifications of “Sisu” were as follows:

Displacement: 6100 tons GRT

Length: 90 meters

Beam: 20 meters

Draft: 7.6 meters

Propulsion: Diesel-electric with six generators, totalling 13 000 IHP.

Armament (wartime): 4x 105/50 DP guns, 2 x twin-barrelled 40 Bofors AA-guns, Depth Charge racks

Other: Fitted with airplane hangar and crane for a small floatplane

In addition to regular operations during winter, the ship was also used for state propaganda purposes during summers. Of these trips, the Greenland expedition during the summer of 1937 gained widespread publicity outside Finland. However, the best-known trip was the visit to the New York World’s Fair in the summer of 1939, where she had a large number of visitors. “Sisu” was a rare sign of peaceful engineering during the period in which storm clouds were already gathering over Europe. Following the New York World’s Fair, “Sisu” continued on to Brazil and Argentine, carrying a Finnish export show designed for South American markets. In August 1939, with the danger of war with the Soviet Union looming ever larger on the horizon, orders were sent for “Sisu” to return immediately. However, due to a collision with a British vessel, “Sisu” had to be repaired in an Argentinian shipyard. Repairs were completed by late October 1939 and with war looming with the Soviet Union, “Sisu” was directed to proceed to Narvik.

The entry into service of the three other icebreakers of the Sisu-class, “Urho”, “Otso” and “Kontio”, was delayed somewhat due to changing priorities for construction, with Urho entered service in 1934, Osto in 1937 and Kontio only in 1939. However, by 1939, Finland would have eight powerful icebreakers in service, together with the six smaller and older ships which were retained for local duties in ports and the archipelago. They would prove invaluable in the Winter War.

IV – Naval Construction between 1928-1933

Finland first obtained a navy of sorts during the Finnish Civil War of 1919, when a number of elderly gunboats and torpedo boats of the Russian Tsarist Navy fell into White Finnish hands. Almost all of these captures came in shipyards and harbors where the vessels had been laid up without crews, and not of active warships. By the early 1920’s, these ships had become thoroughly worn out and most of them went to the scrapyard in Turku.

Hjalmar von Bonsdorff (1869 – 1945)

The Finnish Navy’s first commander, Commodore Hjalmar von Bonsdorff (who had served from 1891 to 1898 in the Imperial Russian Navy and then joined the Finnish Pilot Service. He fought on the 1905 Russo-Japanese War and in WW1 (where he commanded a Destroyers and then the defence of the Danube River mouth), was a Colonel in the Army during the Finnish Civil War and was appointed to head the Navy. He resigned in 1919 with the rank of Admiral and from 1925 until his death lived in Soderkulla Manor), presented a plan in 1919 for a navy based around a division of armored coastal defense ships, with a squadron of large destroyers and 40 torpedo boats, plus submarines and minelayers. It went nowhere at the time, but the basic concept, heavy guns supported by submarines and torpedo craft, stayed with the next generation of Finnish naval planners.

In the mid-to-late 1920’s, the Finnish High Command saw two specific direct naval threats and a third, indirect threat, requiring naval forces: a possible Soviet landing around Helsinki, and another Swedish attempt to seize the Åland Islands (repeating their 1918 adventures in the Finnish archipelago, driven off by German threats). A third more indirect threat of lesser importance was from the Soviet Navy fleet based out of Murmansk which could threaten Petsamo, Finland’s only Arctic port or the alternative access through the Norwegian port of Narvik. As part of the strategic naval planning that went on in conjunction with the development of the “Naval and Merchant Shipping Act,” it was determined that the objective of the Finnish Navy was to protect the Finnish coast and Finnish shipping against the Soviet Baltic Fleet and any Soviet Naval Forces based at Murmansk, which provided the major conceivable naval threat. Although the Navy leadership initially preferred coastal monitors armed with 10″ guns, (OTL Väinämöinen-class) the support from the ship-building industry for large naval ships had waned due to the Merchant Navy law which produced lucrative large civilian orders for the Finnish shipyard industry almost immediately. The ordering of large warships, construction of which would demand special techniques of little use in civilian shipbuilding was no longer considered necessary by the shipbuilding lobby.

Icebreakers were the initial government-funded “masterpieces” of the Finnish shipbuilding. Smaller ships, on the other hand, would allow government funded work to be spread out over more shipyards. And in this, the Finnish Navy made a number of strategically sound decisions. The 1927 Naval Construction Plan put the emphasis on fast submarines, a strong destroyer flotilla made up of fast, modern and heavily armed destroyers, mine warfare and a strong anti-submarine component with the tactical objective of both bottling up the Soviet Baltic Fleet in Krondstadt and neutralizing the Soviet submarine threat in the event of war. A secondary objective was to deal with any Soviet naval elements in Murmansk.

The Finnish parliament finally approved the details of an ambitious naval construction program in September 1927 in the “Naval and Merchant Shipping Act.” This program was later updated in 1934 as part of the overall ongoing restructuring and rebuilding of the Finnish Armed Forces to face a potential invasion from the Soviet Union (updates in 1934 saw the addition of large numbers of small wooden Motor Torpedo Boats, Motor Gunboats, Fast Minelayers, Anti-Submarine Patrol Boats and a large number of small Coastal Torpedo Boats).

Decisions on the placing of orders for naval vessels were made in conjunction with the allocation of orders for the new Icebreakers that were also being planned. While the Icebreaker orders were assigned to the Hietalahden Laivatelakka yard, the first naval order, for three of what was eventually planned to be nine submarines, was placed with Crichton-Vulcan. In 1927, the Crichton-Vulcan yard in Turku began construction of the first three submarines of what was planned to eventually be a total Flotilla of nine Submarines. The first three submarines, the Vetehinen, the Vesihiisi and the Iku-Turso, were 705-long-ton submarines designed by Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw, based on the German Type UC III.

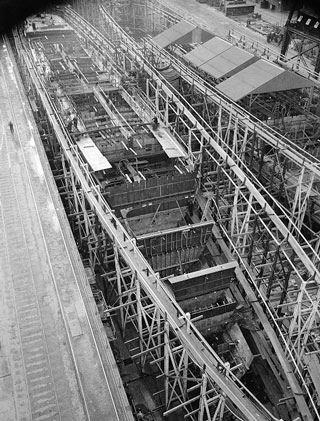

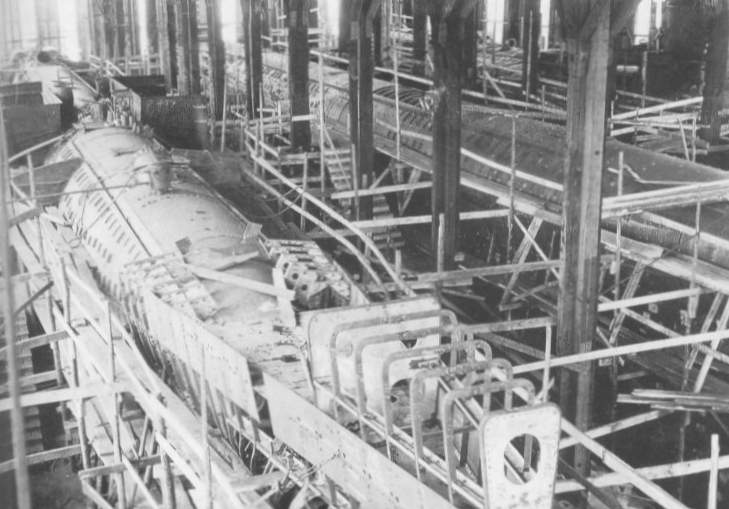

The three Vetehinen class submarines side-by-side in the specially built construction shed

As has been mentioned, Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw or IvS, was actually a German “front company” in the Netherlands, established for the purposes of maintaining German submarine technology and designing a new submarine fleet. (According to the Versailles Peace Treaty, Germany could not have various weapons, including submarines, after World War I and this resulted in moving armaments’ research to foreign countries). The objective of the Germans was to maintain and develop German submarine expertise and know-how and to circumvent the limitations set by the Treaty of Versailles. While the Finns were no doubt aware of this, the desire for a new and modern submarine type suitable for use in the Baltic by the Finnish Navy meshed well with the German intentions.

The class was based on the German World War I Type UB III and Type UC III submarines and would serve as the prototype for Type VIIA submarines. The design work and the supervision of construction for the first three boats was done by Germans. The submarines displaced 716 tonnes submerged, had a speed of 12.6 knots surfaced and 8.5 knots submerged with a range of 2,917 kms surfaced and 139 kms submerged. The engines were two x 580 HP Polar-Atlas Diesel (515 rpm). 6 cyl., four-stroke’s with 2 x 360 HP Brown-Boveri electric motors (420 rpm). The submarines carried 16 tons of fuel and were equipped with 62 x Tudor AB 2 Battery Cells.

Crewed by 30 men (3 officers, 5 senior petty officers, 9 petty officers, 13 men), they were armed with 4 torpedo tubes and 6 torpedos, could carry up to 20 mines in mineshafts (One shaft could take three 650 kg mines or one 850 kg and one 650 kg mine). Guns consisted of 1 x 76mm Bofors, 1 x 20mm Lahti Madsenand 1 x 12.7mm machinegun. Construction at Crichton-Vulcan took place under German supervision, one of which supervisors was newly-retired German Navy Lt. Hans Schottky. The submarines were of riveted construction. During the design phase the size of the boat increased many times and therefore the diesel power had to be increased from 530 hp to 580 hp. In addition the pressure hull strength calculations had to be done again and as a result, nine frames had to be strengthened. Construction took more than three years to complete because of the harsh winters and local inexperience. There was a steep learning curve for Crichton-Vulcan, but much valuable experience was gained in the process.

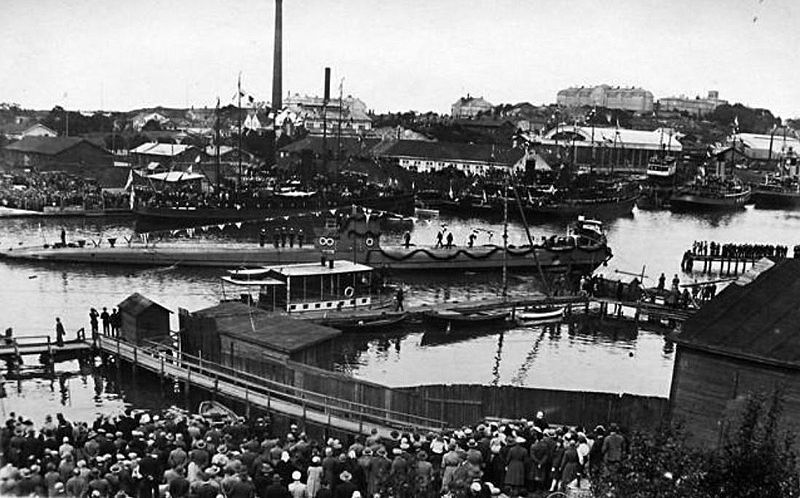

Finnish submarine Vetehinen shortly after her launch in Crichton-Vulcan shipyard in Turku, Finland. 1 June 1930

The Iku-Turso at sea on pre-war exercises, commanded by Lt-Cdr Pekkanen

The Vetehinen, the Vesihiisi and the Iku-Turso were commissioned into service over 1930 and 1931. With the experience gained from the construction of these submarines, a subsequent order was placed for the remaining six submarines in 1930, with one submarine per year to be delivered by Crichton-Vulcan through the period 1932 to 1937. Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw pushed for an improved design – German intentions were to use the Finns to test out a modern submarine type, technology and standards were to be new and not based on the World War I designs used for the three earlier submarines. Commander Karl Bartenbach, who had “retired” from active service in the Reichsmarine, worked as secret liaison officer in Finland. His official title was Naval Expert of the Finnish Defence Forces, and it was under his leadership that remaining six submarines of the order were built in Finland.

The official decision to proceed with the next submarine, the Vesikko, was made in 1930 after several meetings between IvS, Crichton-Vulcan and the Finnish Government (largely in the shape of the “Defence Triumvirate”). The construction of Vesikko began at the Crichton-Vulcan dock in Turku in 1931. There were substantial improvements in both the design and in construction techniques, with Vesikko becoming one of the most advanced submarine designs of its time. Not only was she rather larger, with a more powerful engine and much larger fuel tanks, enabling offensive patrolling to be undertaken, her maximum diving depth was over twofold when compared to earlier German submarines, and its hull could be built completely by electric welding, without rivets – this increased the ability to resist water pressure, decreased oil leakages, and made the construction process faster.

Vesikko was completed in late 1932 and tested in the Archipelago over 1933, when she entered service. The next submarine delivered, Saukko, was identical to Vesikko and was delivered in late 1933. In addition to construction improvements, these two submarines were fitted with four bow and two stern torpedo tubes. The next two submarines, delivered in 1934 and 1935, were identical to the German Type VIIA Submarines (they were in fact prototypes for the German Type VIIA) and were fitted with four bow and one stern torpedo tubes, carried eleven torpedoes and were capable of 17.7 knots surfaced and 7.6 knots submerged. The remaining two submarines, delivered in 1937 and 1938, were similar to the German Type VIIB, with an additional 33 tons of fuel in external saddle tanks adding 2500 miles of range when surfaced and with two rudders for greater agility. They also carried fourteen torpedoes.

Type VII-B Submarine

During the Winter War, the two Type VIIB’s with their longer range and endurance and higher surface speed were based out of Petsamo, They took the Soviet Navy completely by surprise with their repeated torpedo attacks on Soviet transport ships carrying the infantry intended for the attack on Petsamo (indeed, some accounts theorize that the Soviets never even realized the submarines were there as the Ilmavoimat attacks from the air seemed to be the focus for their defensive efforts – in point of fact, it is unlikely that the truth will ever be determined as there were no survivors from the Soviet task force – those survivors from sinking ships that made it into boats were repeatedly attacked from the air by Ilmavoimat aircraft until all boats were sunk. Survivors in the water died within minutes from hypothermia).

In 1938, there was some discussion within the Navy regarding further submarine orders but at this stage, emphasis was on continuing construction of Destroyers, Anti-submarine Corvettes and Gunboats – and proposals for further submarines were shelved. Nine submarines were regarded as a sufficient deterrent. In the event, the deterrent was NOT sufficient, but the Finnish Navy’s submarines would serve their purpose more than adequately in the Winter War.

V – Construction of the Finnish Cargo Shipping Fleet – 1933-1939

After the construction of modern ship-building facilities and the experience gained in modern shipbuilding technologies through the construction of the initial ships of the Icebreaker Fleet and the first series of the submarines, SPAL and SEAL placed large scale-orders with the Finnish shipbuilding industry beginning in 1933, with deliveries planned to begin in 1935. The long lead time had ensured that the cargo ships to be built would incorporate the latest technological advances in commercial shipping design and construction. Due in large part to the state’s taking part, development risks were taken and the designs were very advanced for the period. The shipbuilders also took full advantage of the state funding provided to introduce new constructions technologies, such as electric welding, into commercial use. The promise of a series of orders for large cargo ships had already motivated Wärtsilä Oy to purchase a license to produce Burmeister & Wain diesels in Finland.

Due to increased trade volumes, initial plans were to order fifteen cargo ships for both the South American and North American traffic. These ships were to represent two different standard classes. For North-American traffic the choice of ship type was to be a 7300 DWT ship, capable of operating from most of the shallow ports of the Bay of Bothnia without significant additional investment in dredging – and capable of being effectively supported by Karhu-class icebreakers. As required for Finnish conditions, the class was ice-reinforced to Class 1A.

SPAL-class specifications:

Displacement: 4700 BRT / 7300 DWT

Length: 140 meters

Beam: 17.5 meters

Draft: 7.2 meters

Engine: One 7000 ihp Wärtsilä diesel

Operating speed: 16,5 kts

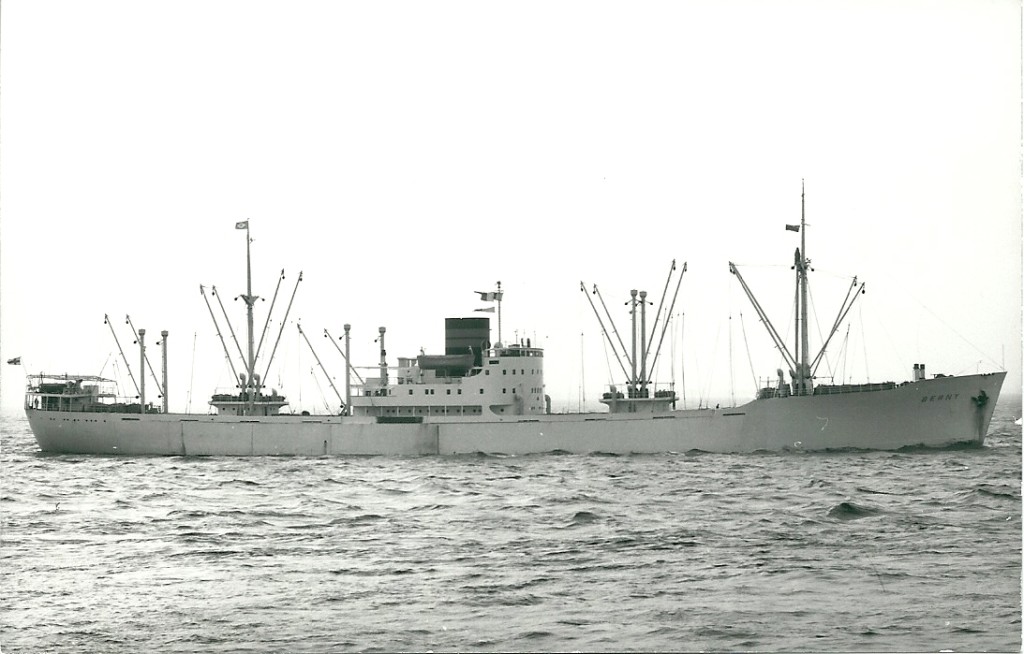

M/S Berny of SPAL in Mäntyluoto harbor during the summer of 1936. The livery color of SPAL was changed to white to mark the new shipping era. Berny was the second ship of the SPAL-class and did not have the electric cranes for which the SPAL and SEAL-classes became well known

The fifteen SPAL-class ships ordered were delivered between 1935-1937. From number three of the class forwards, the design was improved by the installation of new cargo space and loading arrangements to make full utilisation of the development of ports in both the USA and Finland. The introduction of electric cranes instead of derricks, and the use of steel cargo covers, all helped to optimize cargo handling significantly, thus reducing cargo costs. Electric cranes were installed on all newly constructed SEAL ships as well. The SEAL line was to be served with slightly larger and faster ships of circa 10 000 DWT class as the distance from Finland to South America was significantly longer. Following the Japanese fashion, the ships had a single shaft and sleek lines. They also had a white livery similar to SPAL ships. The fifteen ships ordered were delivered between 1937-1939.

SEAL-class specifications:

Displacement: BRT 6000 / DWT 10000

Length: 141 meters

Beam: 19.6 meters

Draft: 8.3 meters

Propulsion: Two Wärtsilä diesels on single shaft, 11 000 IHP

Service speed: 18kts

M/S Arica of SEAL just after trial runs. She reached a speed of 21kts in trials.

Both SPAL and SEAL class ships were equipped to take 12 passengers, as was usual for cargo ships of the time. Also in line with customary practice of the era, the ships were prepared for possible wartime use through the inclusion of preparations to carry armament: a 105/50 DP gun in stern and bow positions, and positions for four AA-machineguns, two on each side. The purchase of armament and the training for gunnery crews was to be funded and arranged by the Navy in the event of war.

In 1936, due to the success of the SEAL and SPAL Lines, a new state-subsidized line to the Far East was inaugurated (Suomen Kauko-Idän Linja, SKIL), mostly in order to carry the rapidly growing Finnish-Japanese trade. Initially the line was to operate with six cargo ships similar to the existing SEAL ships. Orders were placed for six ships in 1937, but due to a backlog of orders, construction could not begin until 1939 and indeed did not materialize before the start if the Winter War. SKIL began operations in 1936 using the Hog Islanders as they were released by SEAL and SPAL. SKIL would also acquire oil tankers for the growing trade in oil from the Black Sea and the Persian Gulf to Japan that took place through the 1930’s.

Luleå in Sweden. With Finnish icebreakers in service, this port could be used almost all year

The skills acquired in the construction of icebreakers and large merchant ships also found use in the construction of smaller ships and in the construction of ore/bulk carriers used to carry iron ore from Finland and Sweden to Germany. While in general the Finnish shipping companies operating in European waters used smaller ships, often purchased second-hand and with low crewing costs due to the use of Finnish crews, the situation was changing by the late 1930’s. First, as the demand for Finnish sailors and for worker in general increased as the Finnish economy grew, pay scales were on the rise, making the operation of older, smaller, crew-intensive ships not as attractive as previously. A second factor was that, by the late 1930’s, shipping in general was a growth sector as governments around the world pumped money into heavy industries and the shipping sector grew increasingly competitive.

Yet another factor was that with the new Finnish icebreakers in service, Luleå in Sweden (and Finnish ports in the Gulf of Bothnia) could be kept open in all except the heaviest winters. This led to increased all year round shipping, with consequent increases in demand for new ships as the new Finnish iron ore mines came into production, the steel mill at Tornio opened (with steel exported and coal imported). With the demand for smaller coastal freighters also increasing, smaller shipyards scattered around Finland also benefited, with small freighters similar to that below in demand. With government support, smaller shipyards took on increasing work and also subcontracted to the larger yards on pieces of large projects – a business model that has continued through to today.

Small coastal freighters were also in demand

VI Soviet Interests – 1936-1939

From 1936 onward’s, the expansion of the Finnish metallurgical and shipping construction industries attracted the interest of the Soviet Union. The Third Soviet Five Year plan was to be focused on the building up of armaments and a gigantic Soviet Navy – and the Soviet Union planned to buy merchant shipping outside the Soviet Union to fulfill cargo shipping needs as Soviet shipyards were filled to capacity with military orders. Finnish shipbuilding, with its focus on ice-reinforced ships, naturally gained attention from Soviet economic planners. Before the the Bolshevik Revolution, the Finnish mining and metallurgical industries had in fact developed to fulfill Imperial Russian needs so the attention was not unsurprising. Still, it represented a drastic change in direction. Before the revolution, 30-40% of Finnish trade had been oriented towards Russia. In the early 1930’s it was around one percent.

Unknown to Finns, the development of the Finnish industrial economy also made Finland a more important target for Soviet expansion in order to meet Soviet “security needs”. This risk was seen by Finland, although more mildly. During the late 1920’s as Finnish industrialization was planned, the risk was seen that Finnish industries might become dependent on Soviet markets and thus orders might be used in future to exert economic pressure against Finland. The risk was countered by the argument that Soviet markets could be used as a testing field for Finnish industrial products which, once established, might be sold more lucratively to the West after new industries were successfully established. Further factors influencing Finland towards closing trade deals with Soviet Union were the need to pay for the increasing amounts of oil being purchased from the Soviet Union and also the acquisition of cheap raw wood for Finnish forestry industries as well as raw materials for industry in general.

The only really negative impacts of these deals were felt only at a much later period. As the Soviets insisted upon old practices (for example, riveting hulls and the use of reciprocal steam engines rather than diesel-electric) the smaller Finnish shipyards which supplied the Soviets with cargo ships did not develop their productive technologies up to a level at which they could have entered the much more profitable Western markets from the 1950’s onward’s. A good example of the benefits to Finnish companies is the example of one of those shipyards, Hollming Works, established in 1934.

In 1922, Master Mariner and Sea Captain Filip Walter Hollming (1894-1951) had recently married his wife, Rauma Helena Yrjönen, and wanted to spend less time at sea and more with his wife. He transferred to Koivisto to head up a stevedoring business but soon expanded into timber milling operations, coming to own several mills. Seeing opportunities with the expansion of the maritime construction industry, already owning a wharf, and aware of the large Soviet orders being placed for a variety of ships, including, surprisingly, a large number of wooden vessels. During Swedish rule and then under the Russians, the reputation of Finnish ship carpentry was at its height. In coastal and outer archipelago areas, peasant carpenters and master shipbuilders were maintaining this tradition as late as the 1930’s by constructing small ships, fishing boats and yachts, while around the lake districts the emphasis was on steam and other types of barge.

In negotiations for the sales of ships to the USSR in 1934, in the lead up to the Third Five Year Plan, the USSR requested the Finnish Government to sell them nearly 100 three-masted wooden sea-going ships. The Finnish Government happily agreed, confident that Finnish carpenters and builders of small wooden ships could meet this demand. Contracts were signed (the USSR insisted on Government to Government agreements, with the Finnish Government responsible for delivery by Finnish companies). However, it soon became clear that the carpenters from the small boat-builders were not equal to the task of building these ships and the Finnish Government found themselves with a problem.

Jaakko Juhani Rahola (1902 – 1973)

New yards would have to be built, the ships would need to be designed and workers trained. The Government appointed Engineer Jaakko Juhani Rahola to serve as Coordinator for the Contract, with Engineer Erkki Jussila as construction director. Rahola (b. 1902, d. 1973) was a Mänttä merchant’s son. He graduated from high school in Tampere in 1920 and completed a Master of Science University of Technology in mechanical engineering and ship-building in 1925. He also completed naval engineering courses at the Military Academy and from 1925 to 1933 worked for the Navy as a Naval Architect and Ship Designer (in this period he designed the VMV-Patrol Boats, the first patrol boats to enter service with the Finnish Navy – more on these later). In 1940 he would be appointed head of the Naval Construction Office (he also completed his doctorate in that year) and in 1941 Professor of Naval Architecture at Helsinki University of Technology. His wife Marianna Lindgren, whom he married in 1926, was the daughter of architect Armas Lindgren and his brother was Rear Admiral Eero Rahola.

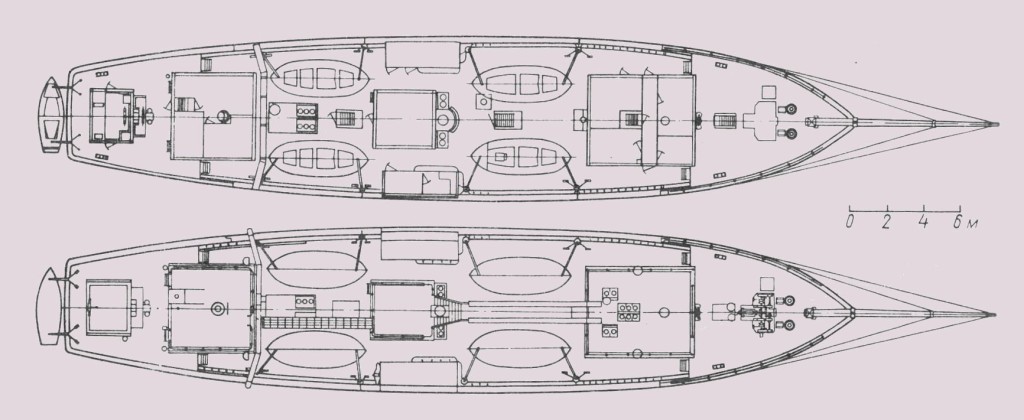

Rahola ordered the pre-planning of the ships to be carried out by Gösta Kyntzell, a renowned boat and vessel contractor; Albin Gustafson of the famous shipbuilding family was to prepare semi-finished models and drawings and was also enlisted to sketch the schooners. Renowned builder Jarl Lindblom was appointed overall design director. It was decided that the wooden ships would be built at four shipyards: LATE in Turku, Hollming in Rauma, Eklöf in Porvoo and Valkon Laiva Oy at Lovisaviken.

In January 1935 three shipbuilding companies – FÅA, AL and Oceanfart – jointly decided to establish a wooden-vessel shipyard at Pansio, called Oy Laivateollisuus Ab (LATE) where 45 of the 90 wooden ships would be built. Jarl Lindblom, who was appointed principal designer and technical director, proved a highly imaginative engineer. He immediately set about applying the most up-to-date techniques available at the time to meet the demanding tasks ahead. This was essential since suitably qualified ship carpenters were in short supply. Jarl Lindblom was appointed to manage planning and drawing operations for all four shipyards. A building permit was granted for the shipyard in February 1945. At the same time, planning the shipyard and the production methods had to be effected for the specific vessels, bearing in mind the different production methods used by the four different yards.

In his yard-planning, Lindblom believed in the principle that ships should be built under cover. This principle would be widely accepted much later; he was a pioneer in this context. In the LATE shipbuilding-hall two lines were built parallel to the shoreline, each of which house four ships side-by-side. In this way eight ships could be built at the same time. Apart from this large construction hall, many technical and social buildings were required – not least, accommodation for the workers. Fortunately, raw materials were not in short supply. The LATE yard was completed on time and the building of the wooden ships began in the Spring of 1936, with a total of 46 ships of the 91 ordered delivered between 1936 and late 1939.

Structural drawing. The upper deck and a top view barquentine “Kropotkin.”

Skilled workers however were in short supply as the shipbuilding industry was expanding throughout Finland. Competent managers for drawing operations and building managers, particularly those with experience in building wooden vessels, were also difficult to find. With the effects of the Great Depression lingering on elsewhere in the Baltic and in Europe, it proved possible to hire some of the needed personnel abroad – many were hired from Estonia, Latvia and Sweden, some from German and the UK and small numbers from elsewhere. Lindblom’s principle of serial production however meant that work operations could be organised in such a way as to enable workers to master their duties quickly.

When production of wooden vessels for the large Soviet order began, it looked as if, in Finland at least, one could be confident of access to production timber. However, it soon became clear that access to rough timber for the hulls, masts and natural trimmings for the 90 ships would be rapidly exhausted. This prompted the call to develop the “glue-wood” method at LATE. That would first require the approval of the recipient, who was as yet unfamiliar with this method. It should be mentioned here that the use of “glue-wood” beams, common in building houses today, had its origins in “glue-wood” production at LATE. Even if sawn wood was readily available, the problem of its rapid curing still remained.

The Hollming Yard in Rauma would go on to build the second largest number of wooden ships ordered by the USSR – 34 in total. This experience would lead Hollming to extend into building wooden Motor Gunboats and other such small wooden ships for the Finnish Navy in the late 1930’s and through WW2. The Hollming Yard was, in practical terms, completely different from that of LATE. Hollming was brought into the ship-building enterprise by an old friend, Kaarlo Pulli, who had previously built wooden schooners and who was considering the possibility of helping out with the construction project, Pulli’s proposal to Hollming was that “We’ll bring in Captain Hugo Pontynen and build the vessels.” Pontynen had been harbour captain in Koivisto; not only that, he had also served as sea trial inspector, hull inspector, classification surveyor and compass adjuster.

F W Hollming Oy was set up, with Filip Hollming as the managing director and Kaarlo Pulli as the Technical Manager. Another friend with experience wood procurement for ship-building, Mannonen, joined them, as did Pontynen, who was highly qualified in matters relating to equipment, monitoring and testing. These four decisive men sought to hold talks with Rahola and Jussila. The latter warmly accepted the quartet’s offer. The Rauma town council granted them a lease for 1.5 hectares of land and a week before the order was received, work was already underway to clear the shipyard area. Many other formalities would be sorted out later. Word of this new place of work spread quickly to Koivisto shipbuilders, who gladly seized the chance to worked at a job in which they were masters. Skilled workers from around Rauma joined the team. As early as June 1935, the keel was laid for the first two wooden ships.

In Koivisto, vessels had long been built along the open coastline without any changes to yard organisation. This would prove to be the shipyard’s strength. While the owner in Koivisto had built one vessel at a time using a certain number of workers, now every available working adult was being recruited to work in one single location to build a whole series of vessels. Initially, there were no drawings, not that they needed them. The advantage of building vessels without drawings has become part of certain well-known anecdotes. Kaarlo Pulli, the technical director at the wharf, had already studied books on shipbuilding; even before accepting the challenge, familiarising himself with the stipulated regulations on wooden vessels. Pulli had a fine handwriting style. However, when someone, who had completed a detailed drawing showed his draft to a supervisor named Kukko, the latter exclaimed: “Have you already drawn what we have yet to build?”

Between the parallel berths – the length of three vessels – a slipway was constructed for wagons. A maximum of six hulls were erected at one time at the wharf. The first launch took place in June 1937 in the presence of staff and satisfied representatives from Rahola’s contract management team and the Soviet Union. Rough timber wood was required – straight and crooked. August Mannonen knew where he needed to look. Baron Cedercreutz’s forests in Kjulo was the first port of call. Mannonen had in his pocket one of the expropriation permits acquired from the Government so he could, when needed, buy the stamped stocks. As in the case of LATE, mentioned above, everything was in short supply, making it difficult to obtain work machines and the like in time. At Hollming though, the start-up was not so much due to the demanding conditions, but rather a lack of basic tools.

They were forced to turn to the black market; and as they could not get axes they had to order one thousand before the factory at Billnäs went along with the production of axes.

Somewhat surprisingly, Jarl Lindblom and others described the yard at Hollming as “old”; as mentioned above, F.W. Hollming Oy in Koivisto was a dispatch and stevedoring business, and Filip Hollming a sawmill owner. Although Pulli and Mannonen had built individual vessels for their own use, there was no actual shipyard in Koivisto. This must have been a great disappointment to Lindblom, who found that work at his planned yard, for which he had high hopes, should suffer serious delays due to insurmountable obstacles.

As it was, before LATE had handed over their first schooner, the other three yards had already built 15.

At the same time as they built the ships, Hollming built apartments for their employees and their families to live in, repaired and extended buildings in the shipyard area and even built Rauma’s City Hall. With the Winter War and WW2, the shipyard facility was extended and as well as wooden Motor Gunboats, Torpedo Boats, Minelayers, Minesweepers and Infantry Assault Craft, Hollming would go on to built steel ships, including large landing craft for the invasion of Estonia. Post WW2, the company continued to expand and Hollming is still in business today.

Hammars: In December 1934 August Eklöf from Porvoo received an inquiry from Rahola about the possibility of building wooden ships at the company shipyard in Tolkis. The company was, from the outset, not interested since it would be more sensible to channel their resources to meet the growing demand for sawn timber. Besides, the yard at Tolkis was small and would not cope with a serial production of large wooden ships. In the end, it was considered in the national interest to be more practical to build a new wharf at Hammars, five kilometres away. Two four-masted schooners had been built there 25 years earlier, but nothing remained of the previous yard. As a result, it did not seem inappropriate to call Hammars an “old wharf”, even though various key people were taken on from the Tolkis wharf. One example was engineer Kyntzell who had made the first sketchings of the schooners for the contract and was now appointed yard director, despite the Tolkis wharf operating to some extent as a sub-contractor for Hammars.

The building of yachts and small wooden boats and schooners at the time continued to be active in Porvoo and Sipoo. Eklöf hoped to engage local master shipbuilders and those who had built boats for the purpose of constructing the wooden ships for the USSR. However, most of them tended to operate as self-employed shipbuilders who constructed boats for themselves for the subsequent transportation of sand and wood. During the five-year period of ship building at Hammars, 35 private boats were built in Porvoo and Sippo. It was shipbuilder Karl Mickelsson from Emsalo who expertly set in motion work operations. Another key expert in getting things underway was slip master Evert Johansson from Tolkis. Migrants from Carelia and Estonia were taken on at Hammars. The pace of work at Hammars was equal to that at Hollming. For the first two years they lived with their broad axes in their hands.

The laying of the first keel took place one month before that at Hollming and the first launch five days after that at Rauma. A gold medal was awarded for handing over the first schooner “to cross the starting line”. The first wooden ship from Hammars was handed over as early as 30th August 1936, but it was sent straight back due to a mechanical bearing failure which meant that the final departure did not successfully take place until the end of September, a couple of days after the transfer from Hollming. Seven wooden ships would be built at Hammars for the USSR. Following completion of orders for the USSR in early 1939, Hammars, as with other small yards, would switch to emergency war production, falling under the control of the Office of Naval Construction.

Valkom: The fourth wharf to build wooden ships for the Soviet order was Valkon Laiva Oy at Valkom, Pernaja. The founders were Repola-Viipuri Oy and Lahti Oy, the latter owning a wide yard area with a narrow-gauge railway by the Valkom harbour. The emphasis had been on building 1000-tonne composite barges; however, to speed up the process of wooden ship construction, the Valkom yard was commissioned to build four sailing vessels. Engineer Erkki Kinnunen became managing director of the company while the post of technical director went initially to engineer Teppo Riki and later to engineer Lassi Vesamaa. The Lahti Oy set-up was responsible for the procurement of wood products.

The start-up of work and formal decisions also took place here in a rather unusual order. In April 1935 construction of the wharf began, in July the order for four schooners and three barges was received while the shipyard company itself was established only on 20th August 1943, when the keel was laid for the first schooner. It was a question of starting from scratch since there were no work machines, workshops or places of accommodation for the workers. Even here, help was provided by islanders from the Carelian archipelago. Although they worked by hand, the pace was brisk. By December they had laid keels for all four schooners – the first being handed over in the following year (1936), the last in January 1938. Meanwhile all four 1000-tonne barges were also completed.

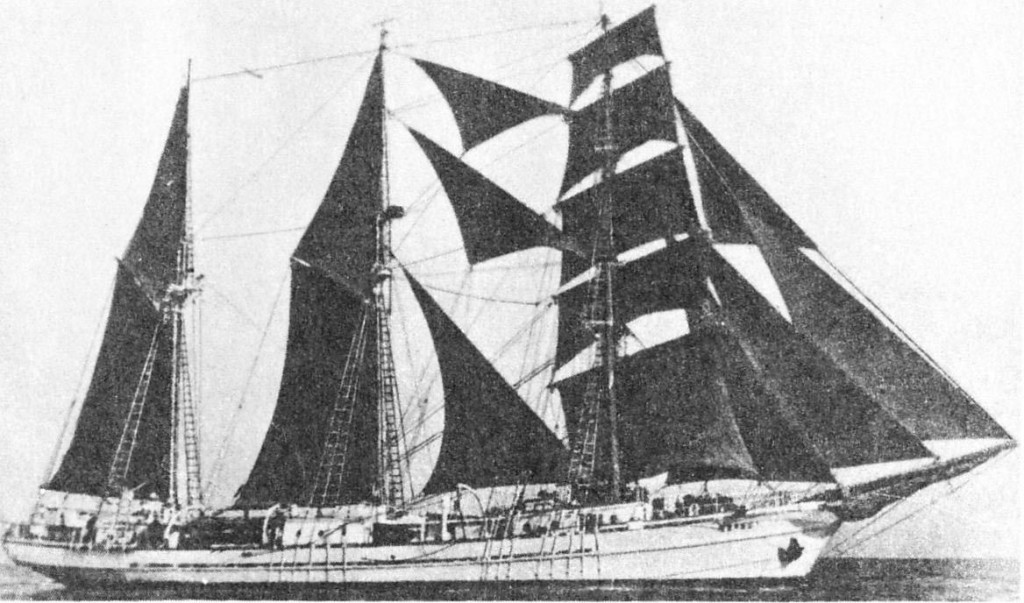

Seagull

These sailing vessels were schooners, square topsail schooners and barquentines and while most of them have disappeared, a few are still around. They displaced around 600 tons with a total sail area of 822 sq meters, with an auxilary 225hp 3-cynlinder June-Munktell engine. They were mostly used as supply vessels for the Russian fishing fleet, bringing supplies out and returning with the catch. Many of these ships were based in the Soviet Far East, sailing there from the Baltic. A number spent time in UK ports on their way. In 1938, for example, the auxiliary schooner Zhemchug was at Hull 12–25 January. She arrived at Brixham for shelter on 29 January, but dragged her anchors and drove ashore on the breakwater. She refloated on the rising tide and sailed on the 30th, but within hours was again in difficulties, and the Plymouth lifeboat was launched. In the event, she made her own way back into Tor Bay, and lay at Dartmouth until 11 February, when she transferred to Plymouth. Her sisters Aktinija, Midija, and Ulva had arrived there on 23/24 January, accompanied by the steamer Umba, and the whole flotilla did not sail from Plymouth until 12 March. They also sailed the Baltic, the Black Sea and the North Sea.

OTL Note: If you’re interested in the real history pf these schooners, built as war reparations in the immediate post-WW2 period, see this article and this thread on shipsnostalgia. Some of these ships were used as sail training ships (see Russian website on these here). For this ATL, I’ve shifted them 10 years earlier – and the USSR pays for them! One of these schooners, Vega had been given to Finland by Estonia in 1997 and as of 2012 was being restored in Pietarsaari (Jakobstad), 430 km north of Turku. Another of these schooners, Meridianas, can be visited at Klaipeda in Lithuania.

Heavy Industry and Development in North Finland

The new Karhu-Class of Finnish Icebreakers which came into service from 1932 were large and powerful enough to keep open sea-lanes large enough for transoceanic cargo ships to pass through. Prior to the introduction of these icebreakers, North Finland had had to rely on rail traffic (with expensive operating costs during the long cold winters). From 1932 on, Finnish icebreakers were capable of keeping the Finnish ports of Tornio, Oulu, Kemi, Oulu, Kokkola, Vaasa and Mäntyluoto open throughout the winter. This completely changed the economic landscape, offering the potential to expand wood-based exports not only in quantity but in quality. This resulted in increased demand for wood, which was available in abundance in Northern Finland but which had previously been uneconomical to transport. With year-round shipping now available, there was an increased demand for motorized transportation, which in turn led to further expansion of the Ford truck factory in Helsinki (utilizing knock-down kits imported from the USA) as well as a boost in sales for the Finnish SISU truck factory.

Together with the sea-lanes opened up by the Finnish icebreakers, the Swedish icebreakers Atle and Ymer were able to keep the Swedish port of Luleå open throughout the year. Thus the necessity for shipping Swedish iron ore through Narvik during winter almost disappeared, as most of the Gällivare iron ore mined by LKAB was destined for German markets. The combination of the modern Swedish port of Luleå and winter navigation in Bay of Bothnia being available opened up a new economic possibility – the establishment of a steel mill utilizing both low transportation costs and the projected hydro-electric power output of the Oulujoki and Kemijoki rivers. This combination was due to fact that the ships fetching iron ore from Luleå for transport to Germany lacked freight to be carried northwards and this offered the possibility of cheap transport of German coal on the return voyage into the Bay of Bothnia.

In Luleå itself the modern ore conveyor belts were reducing loading costs for iron ore, emphasizing transport costs instead of loading and unloading costs. At the same time the international demand for steel was rising and constructing a brand new steel plant from the ground up offered the opportunity to utilize the latest technical advances for high efficiency. Another factor was that Northern Finland was an important voting region for the centrist Agrarian Party which at the time held the primary position in the Finnish Cabinet. To create broad support for the North Finland steel mill project, the Agrarians created an unholy alliance. To the Social Democrats, the Agrarian Party stressed the importance of continuous industrial development and the jobs that would be available for industrial workers. For the National Coalition the importance of industrial strength for national defence was stressed. For the Swedish People’s Party, the steel mill was to be a demonstration of Nordic co-operation, which indeed it was. In usual Finnish style, as private capital was lacking, the state provided capital for the venture.

After long and difficult political arm-wrestling it was decided to situate the new steel mill in the city of Tornio on the Swedish border. The location was to take advantage of the short iron ore transport route from Sweden, with a rail connection planned for a later stage and the possibility of using both the Finnish and Swedish electricity networks in the future. Construction was started on May 1931 and the first steel was shipped from the mill in August 1934. In addition to producing bulk-grade steel, mill expansion was already being planned to utilize domestic nickel, chromium, copper, zinc and cobolt mines fully in order to produce high quality special alloys. Chromium, zinc and cobolt were available nearby, copper could be shipped from domestic mines in Outokumpu and the nickel mine in the Petsamo area was being developed.

Strategically, a number of other options were also under consideration in preparation for the development of an even larger industrial complex in the Tornio area, of which the Steel Plant and Hyroelectric construction was seen as only the first phase.

One option being considered was the the linking of the Finnish rail network to the Swedish line to Narvik. Strategically, this was seen as a way to ensure that in the event of a major European War breaking out, Finland would not be completely cutoff as had occurred in World War One after the Bolshevik Revolution. A second consideration was that the expansion of industrial facilities in Tornio and increased intertwining of industries and infrastructures with Sweden would give Sweden a much bigger interest in assisting Finland in the event of a war with the USSR. A third consideration was that with the development of the Petsamo Nickel Mine, the construction of a rail link between Rovaniemi and Petsamo would both enable year round transport of nickel ore to Tormio and would also provide Finland with yet another strategic outlet outside of the confines of the Baltic.