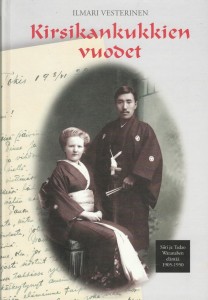

The content of this post is quoted in its entirety from Japan’s Relations with Finland 1919-1944, as Reflected by Japanese Source Materials and authored by Hiroshi Momose, published in 1973 by Hokkaido University, Japan. The original is available at http://hdl.handle.net/2115/5026. Please note that this article is more or less as written (no alternative history here) without any editing by me other than spelling corrections for readability and to correct a few errors that cropped up when I converted the PDF to a text file. Photos and background notes on some of the key personalities referenced are added to the original article by me as I though these would add some value to the article for those readers not familiar with the Finnish and Japanese persons mentioned in the text. Additional commentary added by me is in Italics. I’ve condensed the footnotes on references that were included at the bottom of each page in the original to the bottom of my post (again for readability). Hope you find the article interesting – I ran across it when I was doing a bit of research for my “Alternative History of the Winter War” and thought it was interesting enough (and on a subject obscure enough and little known enough) to warrant posting. There’s little enough on relations between Japan and Finland, particularly through the period covered (1919-1945) that I thought this might interest some readers.

JAPAN’S RELATIONS WITH FINLAND 1919-1944

By Hiroshi MOMOSE published 1973 by Hokkaido University, Japan and as far as I can tell only available in one obscure PDF file which I only came across by scrolling through pages of Google query results…… which makes it so unlikely anyone would ever come across it that I’ve reposted here in the interests of historical research and those interested in this totally obscure topic.

Introduction – Japan’s relations with Finland 1919-1944

In spite of geographical distance, Finland has been thought of by the Japanese people as a friendly European nation. A paradoxical explanation for this attitude may be found in the fact that over a long period of time there have been no particular conflicts of interest between the two countries. One cannot deny, however, that more positive factors have also contributed to it. The Japanese people have been impressed by the religious and educational activities of the Finnish Lutheran mission since the year 1900. Contacts through sport and culture have promoted friendship between the two peoples. A linguistical theory on the Ural-Altaics was once put forward, giving the impression that the Finns were even related to the Japanese. Last but not least, especially in the period between the two World Wars, Finno-Japanese relations were often discussed with a mention of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. Memories of the cooperation between Konni Zilliacus and Motojiro Akashi, a Japanese military attache, survived the First World War. This may be explained in the light of the respective international circumstances which Finland and Japan faced in that period.

Akashi Motojirō, Rakka ryusui: Colonel Akashi’s Report on His Secret Cooperation with the Russian Revolutionary Parties during the Russo-Japanese War

The structure of the Finno-Soviet relations between the two World Wars was such that any international tension threatening the security of European Russia caused an intensification in the feeling of insecurity of the Soviet leaders, particularly regarding the northwestern border, which in turn involved a new Soviet move toward Finland. Therefore, the rise of Nazi Germany, or any other possible crisis in Europe, could have easily led to a situation in which the Finnish people should have felt their future doomed. In the same period, Japan was growing as an actor in the arena of international power politics through economic and military expansion toward the Chinese subcontinent. In the eyes of some Japanese leaders, the Soviet Union cast not only an ominous shadow ahead of them. Especially in the Japanese army, there were powerful circles which had insisted on seizing an opportunity to remove this hindrance and to go so far as to occupy the Soviet Far East, which was wealthy with natural resources. Under such circumstances, exaggerated slogans for “Greater Finland” raised by some extreme rightists in Finland may have served the assertion by Soviet newspapers that Finland was ready to approach Japan, so to speak, as an “old companion in arms.” (1) The purpose of this article is twofold. Firstly, the writer intends to discuss the main features of the diplomatic relations between Japan and Finland in the period coming up to the end of the Continuation War of 1941-1944.(2) Secondly, he wishes to present to readers the Japanese source materials, on which his argument is based, by quoting from the diplomatic documents reflecting views, observations or experiences of Japanese diplomats engaged in the conduct of Japan’s policy toward Finland.(3)

I. Some Japanese Images of Finland

In the period dealt with in this article, very few Japanese visited Finland. Generally speaking, the Japanese people had only little and often inexact knowledge of Finland and the Finns. Japanese newspapers and magazines, however, published generally favorable articles on Finland. Especially during the Winter War of 1939/40 Finland was more familiar than usual to the general public, who read with much interest newspaper articles on “honest and heroic” Finnish men (4) fighting in the snow-covered battleground, and also “intelligent and courageous” Finnish women engaged in the activity of the Lotta Svard.(5) The sympathetic tone of the Japanese newspapers toward the Finns even went to the point, where a cultural and racial identification of the two nations was made. ” Finns are similar in character to Japanese.” (6) The Finns were “essentially Asians” and “Europeanized yellow people.” (7) The landscape of Finland was also introduced to Japanese newspaper readers. Finland was a “country of forests and lakes,” and, Karelia, where the war was being fought, was a “beautiful dreamland of forests and lakes, only a mention of which was enough to stir a Finn.” (8)

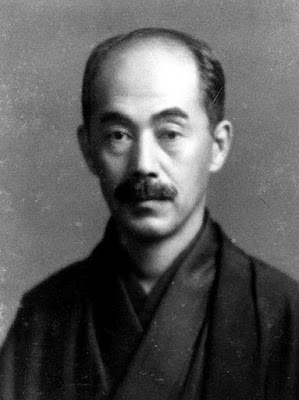

Yanagida Kunio was a well-known Japanese folklorist of the time who looked into Japan’s prehistoric ties with the Finnish people

A peculiar pro-Finnish activity was carried in the Japan of the Inter-War period by some Japanese nationalists imbued with Turanism. It found theoretical expression in, for example, a book entitled “Han tsuranizumu to keizai burokku [Pan-Turanism and the Economic Bloc],” written by an economist. The writer of this book insists…that the japanese should leave their tragically narrow home-islands and to remove to the northern and western parts of the Asian Continent, where their “forefathers” had once lived. For this purpose, however, they had to recover the “forefathers’ lands” from the Slavs by entering into alliance with the Turanian peoples. The Finns, one of those peoples, were to take a share of this great achievement. He writes: “In view of the Finnish determination (the mobilization at their eastern frontier-Parenthesis original) at the time of the recent Manchurian Incident, we can surmise how great a role the Finns could play in a forthcoming japanese-Russian x …. Finns are courageous. But the Finns can never regain Karelia and other territories by themselves ….. In alliance with the Finns we have to destroy Russia, and give the Finns vast territories west of Siberia so that they may build a Greater Finland.” (9) One document entitled” Gunki Gunryaku Keikaku” [A Gist of the Plans of the Military Secrets and Strategies], which a vice-chief of the General Staff (Masaki) handed to a chief of the Staff of the Kwantung Army (Kawabe), reveals an intention of resorting to agitation inside the Soviet Union in terms of destroying the Soviet military power. Poland and the Baltic States had to be mobilized.(10) The above Turanian theory had apparently corresponded with the idea of this kind of military plan. However, a Japanese-Soviet war did not actually break out, and the plan was never realized. The very proposal for a “Turanian Union” set against the prevailing expansionist idea of “a Japan-Manchuria-China bloc” was lacking in actuality, and therefore it remained as a visionary idea with romantic flavor but without influence.

Yanagida Kunio (1875 – 1962) – a a Japanese scholar who is often known as the

father of Japanese native folkloristics,

or minzokugaku

It is interesting to note that an observation forming a contrast with the above one was presented at that time by a well-known japanese folklorist, Kunio Yanagida. Yanagida, who had become intimate with Dr. G. J. Ramstedt, linguist and first Finnish Charge d’Affaires to Japan, published in 1935 an article entitled” Fuinrando no gakumon” [Scholarship in Finland], in which he discusses, in addition to the Finnish folklore, Finnish society and culture in comparison with those of Japan. Japan and Finland, he argued, were two” entirely different” countries. It was not only because Finland was a “new country” with the population of less than 4 million, while Japan was an “old country” with the population of almost 80 million. A more important difference could be found in the fact that Finland had only a small number of soldiers. A country with such a small army could not resort to arms, and therefore it would try to exalt its national glory by means that Japanese people would not think of, for instance, by playing an active part in the field of sports. Finnish patriotism was cultivated through language movements. “Their way of doing things is vastly different from that of Japan, where young people have been led to believe that patriotism means only death in battle (11). Various Japanese individuals who had been to Finland made introductory sketches of Finnish culture and society. Among them is an interesting collection of reminiscences, Fuinrando zakki [A Notebook on Finland], written by Hikotaro Ichikawa, poet and diplomat, who was the Charge d’Affaires to Finland in the 1930s, in collaboration with his wife. (12) In this book Ichikawa admires Finnish social life, remarking especially on the fact that Finnish women, having been socially and politically emancipated, enjoyed equality with men. Ichikawa also speaks highly of Finnish politics and diplomacy. Finnish diplomacy was a “Northern diplomacy” directed toward” independence, freedom and neutrality.” (13) “And even if the country should face difficulties, the wise and superior politicians would frankly give the whole people an explicit idea of how things are. Accordingly there would be at once a natural unanimity among the people.”(14) In his memoirs Ichikawa further writes that the successive Finnish foreign ministers he met, Hackzell, Holsti and Erkko, all entertained a goodwill toward Japan. Eljas Erkko, who was pro-Japanese as well as his father, published in Helsingin Sanomat the full text of Ichikawa’s article, in which he pleaded for the appearance of Japanese goods into the Finnish markets. (15) Antti Hackzell recollected that he had paid his respects to Japan at the time of the Russo-Japanese War. (16) Rudolf Holsti, who was an intimate friend of Dr. Ramstedt’s, had” in fact a surprisingly exact knowledge of Japan.” (17) Japanese people had received such pieces of information as juxtaposed in the above, which had apparently contradicted each other. It should be noticed, however, that even in those pre-War days efforts had been made to make Japanese people familiar with the Finnish culture. In 1932, for instance, the Japan-Finland Society was established to hold monthly meetings in the zenith of its activity. In 1937, a Japanese translation of Kalevala appeared, attracting the readers, young and old.

At the end of this chapter, one more remark may be added that detailed information on Finland had been sent to the Japanese Foreign Ministry by Japanese diplomats in Finland. Monthly reports sent from Finland are an interesting reading in that they were fairly well-informed literature written in Japanese on Finnish affairs of the time. Especially interesting is a plain-spoken report written in the middle of the 1930s by Charge d’Affaires Ichikawa, in which he described the Finnish people’s images of Japan. According to this report “The Finns have generally entertained good feelings towards Japan since the Russo-Japanese War. Frankly speaking, however, this mainly originates from old people and military men who are acquainted with the state of affairs at the time, Even those people have little knowledge about Japan itself.” As books dealing with Japan available in the usual Finnish bookstore, he could only give the Finnish translation of Kanzo Uchimura’s “How I became a Christian,” some booklets by Finnish Lutheran missionaries working in Japan, an anachronistic work “Japani” by ]. E. Aro and the Finnish translation of an anti-Japanese novel by John Paris.

Toyohiko Kagawa was one of the few Japanese authors who had a book (“Crossing the Death Line”) translated into Finnish

Only recently, Ichikawa continues, have there been published a friendly introduction of Japan by Captain V. Brummer, and a guidebook of Japan by S. Salminen, wife of the former Finnish Vice-Consulate General in Shanghai. Among others are the Finnish translations of Toyohiko Kagawa’s Shisen 0 koete [Crossing the Death-line] and Hitotsubu no Mugi [One Grain], which “people here rather tend to see as a description of how the defects of Japanese society have been remedied under the influence of Christianity. Therefore, demands for those works can scarcely be taken for a manifestation of the Finnish people’s respect for our country.” Judging from the indifference of the general public toward the Finland-Japan Society, as well as the fact that the bookstore Akateeminen Kirjakauppa had recorded no sale of books related to Japan, ” [friendly] attitude of the Finnish people must not be based on factual knowledge, but superficial and simply emotional impressions.” The Finnish people lacked eagerness to study Japan. (18)

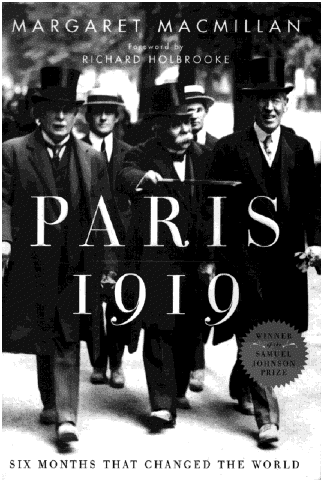

II. Recognition of the Finnish Independence

At the Paris Peace Conference held in 1919, Japan was treated as one of the five Great Powers, which played a leading role in various decisions concerning the peace settlement. Japan’s effort, however, was mainly directed toward acquisition of special interests in the Shantung Peninsula and the South Sea Islands. As for general and European problems falling outside its own interest, the Japanese delegates had essentially been instructed not to interfere in, but only to ” go with the tide.” (19) In discussing Japan’s attitude towards the Finnish questions during and after the Paris Peace Conference, one should also take into consideration Japan’s position of that time as an active participant in the war of intervention against Bolshevik Russia.

The first of the Finnish questions put before the Japanese Government was that of the recognition of Finland’s independence. The Finnish declaration of independence on December 6, 1917, had been followed by the outbreak of the Finnish Civil War, the Finnish expedition to East Karelia and the involvement in the military struggle between Germany and the Allies. After the defeat of the Central Powers, Finland gave up the hitherto pursued pro-German policy and launched upon the new orientation toward the Allied victors. It was against this background of development that the problem of the recognition of Finnish independence was taken up on May 3, 1919, at the Council of Foreign Ministers. (20) All the delegates at this meeting took affirmative attitudes toward the question in view of the recent friendly policy of the Finnish Government and also of the supposed effect of the recognition in preventing the westward expansion of the Bolshevik activities. The Council of Foreign Ministers came to the conclusion that (1) the British and American Governments should recognize the independence and de facto government of Finland, and (2) in dispatching their formal representatives to Finland, the British, French and American Governments would give advice to the Finnish Government with regard to the question of its boundaries and the amnesties to the former Red Guards in the Civil war (21) In other words, the Allied recognition was given not to the de jure but to the de facto government of Finland that room might be left for exerting influence upon the Finnish Government in terms of making it carry out the above two items. Since the Japanese delegate, Nobuaki Makino, had no instruction concerning the independence of Finland, a resolution was made that “the Japanese delegate will communicate the above resolutions to his Government at once so that the Japanese Government may also take same measures.” (22)

Immediately after that resolution Britain and the United States successively gave recognition to the independence and the de facto government of Finland. The Finnish Foreign Minister, Rudolf Holsti, who was staying in Paris, called on the Japanese Ambassador to France, Keishiro Matsui, on May 15, to request that Japan would follow other Allied Powers. (23) Prior to this, Matsui had made a request for examination of this matter by the Japanese Government, (24) which decided to recognize the independence and the de facto government of Finland at the Cabinet Council of May 16. The precedent decisions by Britain and the United States had laid a good foundation for this Japanese decision. (25)

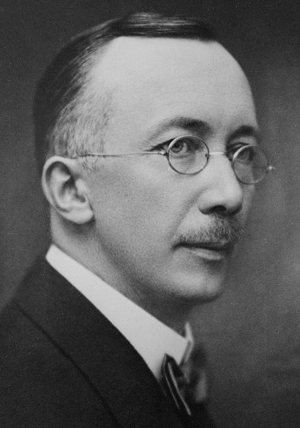

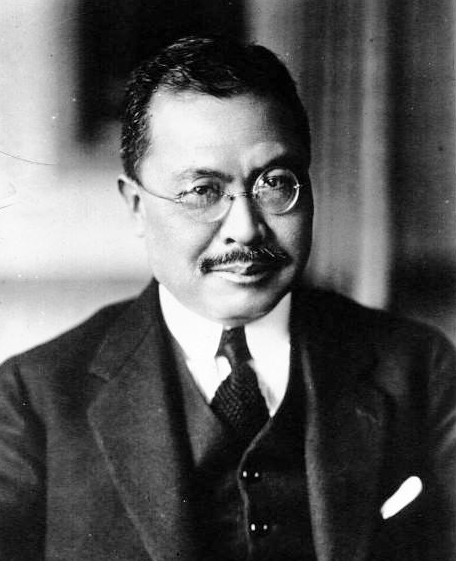

Matsui Keishirō (1868-1946), Japanese Ambassador to France during WW1 and the Japanese plenipotentiary at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. He later served as Ambassador to the United Kingdom in 1925-1928

On May 23, Holsti was informed of this decision by Matsui. On the following day, Holsti returned the call and stated: “Finland has at present the consuls from Britain, the United States, France and Italy, and is going to exchange diplomats with those countries. Further, the Finnish Government intends to appoint in the near future a charge d’affaires to Japan, who will hold additional posts in China and Siam. Accordingly, we hope that the Japanese Government will also dispatch its diplomat to Finland.” To this Matsui answered, “The Japanese Government now seemingly finds it difficult to find spare persons, but your words will anyhow be conveyed to our Government.” (26) Having received Matsui’s report, Foreign Minister Uchida sent an instruction on June 3: “Since we can scarcely spare persons for dispatch as diplomat to Finland, please nswer the other side in an appropriate way. (27) There was Finnish activity toward the exchange of diplomatic envoys also in London. Julio N. Reuter, Professor of Linguistics at the University of Helsinki, who had stayed in London till July 8 in the capacity of the Director of Publicity of the Finnish Government, told Secretary Isaburo Yoshida of the Japanese Embassy, with whom he had become acquainted in the pre-war days: “In London, I expressed my hope to the Finnish Foreign Minister that I would be dispatched to Japan as a minister.”

To Yoshida’s personal comment that, prior to the reception of a minister, the conclusion of a commercial treaty might be demanded, Reuter said, “I. who only love Japan’s way of life, do not necessarily wish to be minister. Since Japan and Finland have little to do with each other on the political level, the mere promotion of intimate commercial relations will serve our purposes. I would gladly proceed as a general consul.” Then Yoshida gave Reuter a copy of the recently concluded Japan-Ecuador commercial treaty written in English, at the request of the latter. Reuter further asked if an official envoy would be sent from Finland from Japan. Yoshida could only surmise that, because of the geographical convenience, the Japanese Minister to Sweden would have, for a time, an additional post in Finland. Reuter promised that things would be arranged thereafter in such a way that negotiations would be carried on through the same Minister. Reuter added that Finland had an intention to provide Japan with wood-pulp, and that, if trade inspectors were dispatched from Japan, he would gladly give them facilities. (28)

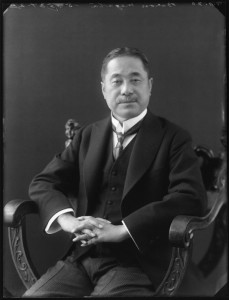

On October 2, 1919, the Japanese Ambassador to Britain, Sutemi Chinda, sent the following telegram to Foreign Minister Uchida: “Prof. Ramstedt, the Finnish Charge d’Affaires to Japan, has requested us to give facilities for reserving a cabin on the ground that he wishes to leave here for his post in October. Have there been any negotiations on exchange of envoys since the recognition of Finnish independence? Please wire back.” (29) In fact, Foreign Minister Yasuya Uchida had not received from Matsui in Paris any new report about the question since the May, when the Finnish Foreign Minister, Holsti, had proposed the exchange of diplomats. (30) But when the Finnish Government repeatedly requested through its Charge d’Affaires in London the reservation of a cabin, (31) the Japanese Government decided, at a meeting of the Cabinet on November 4, “to reply to the Finnish Government that, if a charge d’affaires was sent from Finland, the Japanese Government would receive him, though Japan at present could not afford to dispatch its own envoy.” (32) In this way Ramstedt, a famous linguist and professor at the University of Helsinki, was to go to Japan as the first Finnish envoy to Japan. (33)

Gustaf John Ramstedt (1873-1959) – Finland’s first envoy to Japan, as a Chargé d’affaires, from 1920 to 1929

At Marseille, on December 9, Ramstedt boarded the Iyo Maru of the Nippon Yusen Kaisha – the Japan Mail Line -, together with his daughter Elma, to set out for Japan. (34)

Ramstedt, who had an additional post of Charge d’Affaires to Siam and China, visited Bangkok and Shanghai on his way, and then arrived at Tokyo on February 12. He called on Foreign Minister Uchida on the 27th to hand Finnish Foreign Minister Holsti’s credentials of October 1, 1919, addressed to Foreign Minister Uchida. Immediately after his arrival in Japan, ambassador and scholar Ramstedt started diplomatic work, in which he was unpracticed, by himself and without any assistant.(35) Among the first tasks that confronted him was to get from the Japanese Government the “de jure recognition” of the Finnish Government. On April 11, 1920, Ramstedt made a proposal on the matter to Foreign Minister Uchida. According to the note he presented, Ramstedt had received, on April 4, an instruction from Foreign Minister Holsti, which read: “Though not having a sufficiently clear idea of the difference between the recognizance de jure of a government and that of a state,” Ramstedt requested the Japanese Government to pay “benevolent attention to this question.” (36)

On receiving this letter, Foreign Minister Uchida sent an instruction on May 4 to Ambassador Matsui in France: “In view of the precedent that the question of the recognition of Finland’s independence and de facto government were taken up at the Council of Foreign Miinisters in Paris, this matter may also go through same processes. On the occasion when it is discussed, take proper measures.” From Matsui, however, no report was sent back.(37) On the other hand, Finnish Foreign Minister Holsti sent to Ramstedt a letter dated August 20, in which he explained the state of affairs concerning the recognition of the de jure government of Finland. ” ….. the Great Powers have in fact at different times given this recognition without any reference to the Council.” Britain already gave the de jure recognition on May 5, and the United States, did early in 1920. “Under these circumstances, Japan, which in 1919 followed the example of the United States, is now the only Great Power which not yet has recognized the Government Finland de jure.” Ramstedt was requested to continue his efforts regarding this question. On January 20, 1921, Ramstedt called on Foreign Minister Uchida to hand over a copy of the letter, repeating the request for de jure recognition. (38)

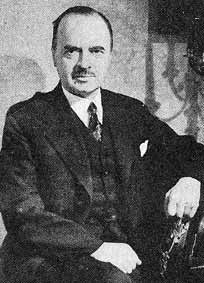

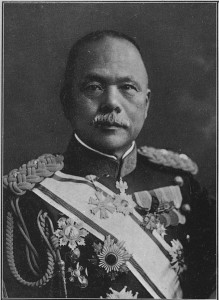

Viscount Ishii Kikujirō (1866-1945), took part in the Paris Peace Conference, served as Preseident of the Assembly of the League of Nations in 1923 & 1926

Under such circumstances Foreign Minister Uchida sent a telegram of instruction to Ambassador Ishii in France in January 12, 1921, ordering the latter to confirm the formal recognition of the Finnish Government and at the same time expressing the opinion: “Finland was previously admitted to the League of Nations at the Assembly. It seems that Japan may now give formal recognition of the Finnish Government at once without waiting for discussion at the Council of Foreign Ministers.” (39) In his telegram in reply, Ambassador Kikujiro Ishii wrote that, according to the view of the French Government, Finland was in all respects an independent state: “In my opinion,” Matsui observed, “the Japanese Government might well give formal recognition at once, now that the country (Finland) was admitted, as stated in your telegram, to theLeague of Nations.” (40) In this way on January 27, the Japanese Government decided to recognize the de jure Finnish government, (41) about which Ramstedt was informed in a document dated February 3. (42)

III. Beginning of Intercourse

Between Finland and Japan, however, there still remained a large question to be solved. An envoy had been sent only from the Finnish side, and this one-sided situation had to be corrected. In spite of its position as an Asian power, Japan, which had come to rank among the Great Powers in international politics after the First World War, was not entirely indifferent to the newly-born European states including Finland. Already around the March of 1919, “A Plan of Dispatch of Imperial Representatives to Finland, Southern Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Other Countries” was examined in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It referred to Finland with the observation: “As for Finland, in addition to the fact that it is a most convenient place from where one can observe developments in and around the Russian capital, and that one can get information about the Russian capital in Helsingfors -the Finnish capital-two or three days earlier than in Stockholm, the said country has now become an independent state. It follows from this that a representative equivalent to a minister should in fact be dispatched, but for the time being the most opportune measures seem to be that of promptly establishing a consulate-general or consulate.” Taking into consideration the intervention to Soviet Russia of the European and American Great Powers, and especially the progress of the British and French design for Southern Russia, the plan argued, “the situation requires the establishment of a consulate-general in Kiev or Odessa as well as in Helsingfors” for the purpose of coming into contact with influential Russians living there and representatives of the “countries concerned,” and also of surveying the situation in Central Asia. This Plan, however, was abandoned with the comment, “unless we have right men for these positions, it will not be particularly effective.” (43) Being faced since May, 1919, by the proposal of the Finnish Government for exchange of envoys the Japanese Government continued to take the attitude that she could not dispatch diplomatic envoys on the ground that it “could not find spare men.” The memoirs of Ramstedt tell how he made efforts to clear the way for the establishment of Japan’s diplomatic office in Helsinki. According to these memoirs, Ramstedt met Foreign Minister Uchida early in the summer of 1920 to request the establishment of a Japanese legation in Finland, but Uchida expressed the view that neither the number of Japanese residents in Finland nor the commercial relations between the two countries were sufficient to require the establishment of a legation.(44)

Hara Takashi (1856-1921), 19th Prime Minister of Japan from 29 September 1918 until his assassination on 4 November 1921

On the occasion of a garden party held in the Imperial garden about a week later Ramstedt hinted to Premier Takashi Hara that he would protest by leaving the country for the alleged reason that Uchida had held his stay in Tokyo to be useless. On the following day Tsuneo Matsudaira, high official of the Foreign Ministry called on Ramstedt to request a detailed explanation. A few days later, Ramstedt answered the question by proposing that the Japanese Government should spare one member of the Legation in Stockholm for a standing representative in Helsinki. (45) No document has come to light in the Archives of the Japanese Foreign Ministry how this very proposal by Ramstedt was dealt with. But Japanese diplomatic documents give interesting evidence that there had also been on the side of Japan various opinions insisting on the necessity of dispatching a standing envoy to Finland. Inside the Foreign Ministry the fact had been reconsidered that it had not dispatched any man to European Russia since the evacuation of the Japanese embassy from Archangelsk, and that it lacked information about Finland and other Baltic areas. (46) In a telegram of April 9, 1920, to the Foreign Ministry, Matsui, the Ambassador to France, proposed that Japanese representatives should be sent to newly-founded states in terms of making Japan carry weight with those countries, for “the Powers are making efforts to compete with each other for advantageous diplomatic and economic position by despatching their representatives to those newly-born states.” (47) From the end of 1920 to the beginning of 1921 the Japanese diplomatic agencies in Stockholm and Paris were active in sending reports insisting on the necessity of sending an envoy to Finland. At the end of November, 1920, Hata, the Minister to Sweden, sent a report by Secretary Kitada on “how to expand our diplomatic agencies in Scandinavia,” in which Kitada advised that the Charge d’Affaire attached to the Legation in Sweden should be dispatched to Finland as well as to Norway and Denmark on the assumption that “the cooperation between Finland and the Scandinavian States mat become closer in future than the Baltic Alliance.” (48) Another and probably more important reporter was Secretary Sentaro Ueda, specialist of the Russian affairs and formerly a contributor to Akashi’s activity at the time of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. Veda visited Finland at the beginning of 1920 to talk with the Finnish Premier, the Foreign Minister and the Chief of the General Staff, the first two of whom “emphasized the agreement of Japanese and Finnish interests in regard to relations with Russia, and further hoped for the residence of a Japanese representative [in Finland-by Momose], for the reason that, having made peace with Russia, Finland was a convenient place for obtaining information about Russia.” (49) On the basis of his experience during his Baltic travel, Ueda drew up a report titled, “The Pressing Need of Establishing Diplomatic Agencies in Poland, the Baltic States and Finland,” and this report was sent to the Foreign Minister through Ambassador Ishii in France. In Ueda’s opinion, while observation of the situation in European Russia was indispensable to the establishment of a line of policy toward Russia, which was an urgent necessity for Japan, the setting up of observation post in Southern Russia was now meaningless, as a result of the collapse of the Wrangel’s Government. Instead, the northwestern territory of old Russia, or Poland, Lithuania, Estonia and Finland increased in importance for the observation of the actual circumstances of the Bolshevik Government. Those territories were now important also in terms of striking a general line of foreign policy, for these became the centres of conflict in European diplomacy or “the second Balkan Peninsula.” Of the three Baltic States, Latvia, which officially exchanged ministers with the Russian Bolsheviks, would be the most convenient place. “In parallel with three independent states on the Baltic coast, Finland is a convenient place for the observation of the state of affairs under the Russian Bolshevik Government. Especially, it is, just as Estonia is, close to Petrograd, which is, next to Moscow, the most important [city] in Russia. In addition, it has not only secured early recognition of independence from the powers with which it has exchanged ministers, but it has also dispatched a minister to our Japan. With our legation already established in Poland [Warsaw], we Japan have to balance it also a legation in Helsinfors.” (50) On the basis of Veda’s report to him, and for the reason that among Swedish information on Russia those coming via Finland had remarkably increased in volume, Hata, the Minister to Sweden, also proposed that one official belonging to his legation should be stationed in Helsinki. The report includes the interesting remark that: On the basis of a rumour that the Japanese Army had an intention of dispatching a military attaché to Helsinki, Ueda suggested that the Foreign Ministry should get ahead of the Army in view of the latter’s “pert behavior” in Reval. (51) After the above twists and turns, the Japanese Government decided, in the Cabinet Council of February 12, 1921, to dispatch an envoy to Finland. The duties of the envoy besides the representation of Japan’s interests, were defined as follows: “In the light of the fact that, since the conclusion of the peace treaty between Finland and the Soviet Government last year, Finland has come to occupy an important position in European Great Powers’ traffic with Russia, it is considered as an appropriate measure that the above Imperial envoy should be charged to collect pieces of information concerning the state of affairs in Russia. In order to carry this out within the framework of the present budget, the Cabinet Council has decided to have the minister in Sweden hold additional posts in Finland for the time being, and to station one of his subordinates in Helsinki in order to have him act for the former.” (52) Thus in company with Secretary Hyoji Nihei, Rytaro Hata, the Minister to Sweden, visited Finland to hand his credentials to the President of Finland. (53 )

The Åland Islands are in the Baltic Sea strategically located between Finland and Sweden at the entrance to the Gulf of Bothnia

Among the events which took place at the beginning of diplomatic intercourse between Japan and Finland was the Aland question. With regard to the conflict between Sweden and Finland over the Aland Islands, at the Baltic Committee of August, 1919, the Japanese member “considered that the Aland question had not arisen directly out of the last War, and that it would not be advisable to come to an immediate decision on a question of territorial changes against the will of the country to which the territory at present belongs,” and the French and Italian members also agreed with the Japanese member from the standpoint that it was impossible to solve this question irrespective of the will of the Russians. (54) Thus the settlement of the Aland question was postponed indefinitely, until later in the autumn of the same year the Swedish Government again began to approach several countries including Japan.

On November 29, the Swedish Minister in Tokyo requested that the Swedish Government’s claim to the Aland Islands be supported by the Japanese representative in case the Aland question came up for discussion at the Supreme Council of the Paris Peace Conference. (55) On Foreign Minister Uchida’s request for an observation on this question, Matsui, the Ambassador to France, surmised that Sweden might have been encouraged to bring up this question again by the favorable British attitude toward Sweden as well as French Premier Clemenceau’s speech in the French Assembly, and advised: “I find it difficult to assure you that it would never be raised for a long time, but I do not think it necessary that at present we should give the pledge of our own accord to support the Swedish claim.” (56) On December 20, the Swedish Minister in Tokyo again called on the Foreign Minister to tell to Kenkichi Yoshizawa, Head of the Department of Political Affairs, that he had again been given an instruction by the Swedish Government to request the Japanese Government to take up the Aland question at the Council of Foreign Ministers as soon as possible (57). The Japanese Government, however, did not go beyond giving a promise that it would convey the Swedish hope to the Ambassador in France. (58) In the early summer of 1920, however, the Swedish Government resumed its pressure on the Japanese Government. Through the Minister in Tokyo, the Swedish Government requested the Japanese Government for assistance in taking up the Aland question at the Council of Foreign Ministers. On June 10, it criticized the arrest of Aland inhabitants by Finnish police authorities, and hoped, on the 14th, that the Japanese Government would consider this problem and “exchange views directly with the Great Powers.” To this, Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Masanao Uehara replied, reflecting Japan’s principle of “going with the tide” in European affairs: “If you mean, by direct exchanges of opinion, official and separate negotiations with Britain, France, Italy etc., Japan at least fears that it will not hasten, but rather delay, the solution of the matter. If you mean the bringing up of the question before the Council of Foreign Ministers of the Great Powers, the Japanese Government, so far as those Great Powers give their consent, has no objection to discussing the matter at an early meeting.” (59)

Around that time, as he recollects in his memoirs, Ramstedt acted of his own accord to provide the Japanese Foreign Minister with materials speaking for the attitude of the Finnish Government toward the Aland question. In the autumn of the same year, Ramstedt further worked upon Baron Tanetaro Megata who was to attend the first Assembly of the League of Nations. Armed with information from Ramstedt, the Japanese delegates very often took floor at the meetings of the League of Nations to discuss the Aland question in favor of the Finnish Government. (60) The Archives of the Japanese Foreign Ministry lack records affirming or denying Ramstedt’s account. Instead, they include reports from Kikujiro Ishii who presided over the 13th Council of the League of Nations. In collaboration with other members, Ishii “established the footing of the Council” to make it have voice in the final settlement of the Aland question, (61)

Matsuzō Nagai (1877-1957), part of the Japanese delegation to the League of Nations in 1920-211 and served as his country’s ambassador in Sweden and Finland from 1925 to 1930

Japanese diplomats dispatched to Finland in the 1920’s wrote in their reports such observations on Finnish foreign policy as: “The policy toward Russia is the core of Finnish foreign policy. It is no exaggeration to say that almost all the foreign policy of Finland derives from its policy toward Russia,” (62) or “The Russian question being a matter of vital importance for Finland, all [Finnish] parties seem to concentrate upon it.” (63) Especially interesting among such existing papers is a report by Matsuzo Nagai, the Minister to Sweden, written in December, 1925, under the title of “A General Report on the Finnish Relations with the Neighboring Countries.” (64) Nagai began the report by giving an outline of Finnish internal affairs. “It is eight years since the Finnish people realized their long cherished desire for independence. Newly born as it is, the institutions of the country seem to have been already well under way, owing to the historical background of it having maintained a system of autonomy even under Russian rule.” The country, however, was faced by the language question, the difficulties in economic development -a lack of diverse industries and a shortage of capital-, and the political insecurity showing itself, for instance, in frequent changes of the cabinet. As for the foreign policy, Nagai quotes from a confidential talk with Foreign Minister K. G. Idman, with a preface of Nagai’s own observation: “The present line of Finnish foreign policy seems to be oriented toward rather the Scandinavian States than the Baltic States.”

K.G.Idman, Secretary of State (1918) and Minister for Foreign Affairs (1925) at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Envoy Extraordinaire and Minister Plenipotentiary of Finland in several cities, such as Copenhagen, Riga, Warsaw and Tokyo

Idman reportedly stated: “Danger to Finland in future is Russia and the Finnish people should always be prepared for it. It follows from this that Finland should attach importance to armament and always give heed to cooperation with neighbouring countries. While it is natural that the Baltic States, in a situation similar to that of Finland, should have planned to ally with us, one cannot but doubt whether the position of the former three small states, though they are independent, is really secure. That is a matter one should consider seriously. We should maintain friendly relations with those countries, but I consider it dangerous, for instance, to ally with them. In time of emergency, can Finland really rely upon assistance from those three states? To arouse the suspicion of the neighbouring Great Power by forming such an alliance, which will make it apprehensive, does no good to us. Therefore, at the Baltic Conference in the beginning of this year, Finland took a half-hearted attitude in regard to this question.” According to Idman, in the field of foreign trade, Russia had once been principal market for Finnish products, but these days Finland had adopted the policy of seeking markets for its staple products elsewhere, and had recently made steady progress in that direction. “The fact that Finland had little need for Russian trade may contribute to prevention of troubles between the two countries.” Idman displayed optimism in his remark on the effect of Soviet propaganda on the Finnish people: “Of course, Finland, as a country neighboring Russia, should watch the Communist propaganda activity, and, in this respect we have been particularly vigilant. In my opinion, however, the Finnish people, who are generally well versed in the Russian state of affairs, will be the last people to be led astray by [Communist] propaganda. Especially in view of the fact that the laborers of this country, who are informed of the discriminatory treatment of the laborers in the Soviet Union to such a degree as one no longer sees even in capitalist countries today, do not seem to admire the Russian system, the danger from such propaganda may belong to the past.” One of the principal tasks of the Japanese branch office in Helsinki was to collect and report information concerning Soviet domestic and foreign policy and international Communist movements. The reports sent to the Japanese Government in the period from April, 1922 to March, 1925 have been on file in the Archives of the Japanese Foreign Ministry under the title of “Intelligence from Finland.” (65) The file consists of various reports concerning Soviet political leaders, the Soviet economic condition, the Red Army, Soviet relations with the Scandinavian countries, etc. These reports are based mainly on Soviet newspapers, organs of the FKP, etc. In parallel with the activity in Helsinki, Russian information was also being collected by the Japanese branch office in Riga, which was opened later than the Helsinki branch. The man dispatched for this post was Sentaro Ueda, who, as seen in the above, had advised the opening of Japanese diplomatic agencies in countries on the Baltic coast. Four months later he wrote to his superior official about the promising future of his activities: ” ….. Everything has been going well since my arrival here ….. The Foreign Minister and the other Foreign Ministry officials of this country are all my old acquaintances. Here are many individuals who are concerned with the Bolsheviks]. Therefore materials are easy to obtain. As was expected, this is an ideal place for the observation of the Russian affairs. I have many old acquaintances in the Russian newspaper office. I have been getting on very well with the chief of the information bureau of the Foreign Ministry.” (66) These pieces of “Riga information” sent until the branch was abolished in 1926 have been filed in four volumes.

Baron Kijūrō Shidehara (1872-1951), a leading proponent of pacifism in Japan before and after World War II and Prime Minister 1945-46. In 1924, Shidehara became Minister of Foreign Affairs

In the Archives of the Japanese Foreign Ministry there is an interesting document, which, confessing the difficulty of collecting information in Helsinki, requests for the opening of a legation in Riga. In May, 1928, one diplomat working in the Helsinki branch wrote in a letter to his superior: “How has the question of the Riga Legation been going along? As you know, Riga is situated on the road to Europe from the Soviet Union, and it has become all the more important spot because of the present situation of frequent conflicts between the Soviet Union and Poland. Information from Moscow may give us knowledge about the Soviet internal affairs, internal affairs, but at present, when the Soviet itself still remains a riddle, we absolutely need the additional measure of stationing a diplomat in Riga for the purpose of studying Soviet activity toward the West and the Western attitude toward the Soviet. This was my strong impression during my observation trip of last year to the territories concerned.” In his explanation of the background to this letter the diplomat complains that the people scarcely speak Russian, even those with speaking knowledge of Russian do not use it, and his ability in the Russian language is of no use in Finland. He tried to learn Finnish, but the different structure of the Finnish language prevented him from learning it easily by analogy with Russian. (67) It was just after the opening of diplomatic relations between Japan and the Soviet Union in January, 1925 that the exchange of envoys between Japan and Finland was faced with a crisis. In the December of 1925, the Japanese Foreign Minister Kijuro Shidehara decided that the Helsinki bureau had to be closed in accordance with the Government’s policy of financial curtailment on the assumption that” the collection of Russian information as one of the main tasks of the Helsinki agency has considerably decreased in significance since the opening of the Legation in Russia.” (68) In February of the following year, however, Ramstedt, Finnish Charge d’Affaires in Japan, called on Foreign Minister Shidehara to request that the agency should not be closed on the ground that the Finnish Government attached importance to its relations with Japan. As a result, the Foreign Minister decided to maintain the agency. (69)

IV. In the 1930 s

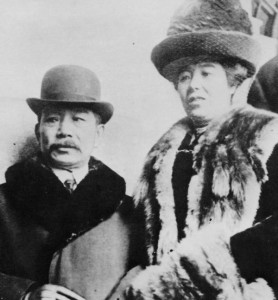

Kintomo Mushanokōji (1882-1962), Japanese Ambassador to Finland 1930-1933. Photo is of Kintomo Mushanokōji (left) signing Anti-Comintern Pact with Joachim von Ribbentrop

In the middle of March, 1933, a Japanese military attache to Latvia learned, on his observation trip on the Baltic coast, a rumor that a commander of the Finnish army had on his own authority concentrated his troops on Finland’s eastern border. It took time until he got at the truth, as one can see from his telegram of March 17, 1933, addressed to the Vice-Chief of the General Staff, in which he commented, “the incident is very strange,” but added the observation, “It may probably be true,” in view of the prevailing idea of Greater Finland, the anti-Soviet and pro-Japanese feeling among the Finnish people -especially in military circles, and the Finnish army’s unique facility for fighting in early winter. (70) A week later, he again sent a report containing the statement that, as a result of investigation, the rumor of the mobilization of the Finnish army had proved true. He continued: “Judging from the words of Colonel Zilliacus, principal of the Finnish Army Academy and a close friend of the President’s, the President, as well as the Government, quite agrees to the attempt to seiz the territory of Karelia, but has seemingly considered it to early to carry it out, coming to the conclusion that a decisive step could wait for the outbreak of a Russo-Japanese war.”

The Soviet–Finnish Non-Aggression Pact signed in Helsinki on 21 January 1932. On the left the Finnish foreign minister Aarno Yrjö-Koskinen, and on the right the Ambassador of the Soviet Union in Helsinki Ivan Maisky.

He even surmised that the mobilization of the Finnish army may have reflected the President’s and the Government’s opinion. The military attache concluded, “This last incident of mobilization should be regarded as clear evidence that, at the possible outbreak of a Russo-Japanese war, Finland will go its own way without hesitation and venture upon the deployment of troops against the Soviet Union.” (71) While this military attache had the reputation of sending enlivening reports, certain military and other circles appreciated the above information, as seen in the above (p. 3) just at the time when Japan’s military action in Manchuria had created a tense situation between Japan and the Soviet Union. From April of 1934, a military attache was stationed in Helsinki in addition to those in Riga and Warsaw, to be engaged in observation of the situation on the Baltic coast. All those Japanese officers were specialists of Russian affairs.

The interests of Japan and Finland, however, did not easily coincide with each other. At the Assembly of the League of Nations held on February 24, 1933, Finland stood for the cause of small states, taking sides with countries condemning Japan for aggression in Manchuria. At an evening reception on the same day, the Finnish Foreign Minister Hackzell made an excuse to the Japanese envoy: It was indeed a pity that Finland could not but take an attitude against your country,” and, “the President also expressed regret on the occasion when the Finnish attitude was discussed.” According to Foreign Minister Hackzell, “In our feeling we might have sided with Japan,” but, “since the League of Nations exists, on principle we could not but take such measures.” (72)

On the other hand, Finland’s will to avoid involvement in the Soviet attempt to organize its neighbouring countries somewhat served Japan. In the beginning of July, 1933, in London, Soviet Foreign Commissar Litvinov concluded the Convention for the Definition of Aggression with its western and southern neighbours. Finland, however, was reluctant to participate in the convention. The official reason for this was that Finland hoped for the position of starting with a clean slate in a possible discussion on the Soviet proposal at the coming disarmament conference. (73) What the Finnish Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hugo Valvanne told Ichikawa reflected the hidden intention of the Finnish Government: “[the Soviet Union]” seems even to use the convention for the purpose of demonstrating the great unity of the Slavic peoples scattered outside the Soviet Union. Therefore, Finland has taken a ‘wait and see’ attitude for the time being, so that it might not be involved in the Soviet propaganda and stratagem.” (74)

The Soviet diplomatic offensive towards its western neighbours did not stop there. On January 7, 1934, the Finnish Minister in Tokyo visited the head of the European and American Department of the Foreign Ministry, to inform: Recently the Soviet Government made a proposal to Finland for the conclusion of a treaty to the effect that, when one of the contracting parties has its independence jeopardized, both contracting parties should consult with each other about the measures to be taken. The Finnish Government, however, replied that, since there had already existed between the two countries the treaties of Non-Aggression and for the Definition of Aggression, it had not thought it necessary to conclude such a treaty.” The Soviet proposal had been made not only to Finland, but also to Poland and the Baltic States. The Soviet Union seemingly intended to neutralize its western frontiers when and if it was threatened from the East. The Finnish Minister further “explained Finland’s friendly attitude toward Japan.” Similiar information was given also to Ichikawa in Helsinki by Eero Jarnefelt, the Finnish Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs. (75) In the following months, Finland remained completely aloof from the negotiations over the Eastern Pact, the geographical scope of which was a matter of grave concern for Japan. As it further pursued a policy of expansion toward Northern China and Mongolia, Japan felt its flank all the more threatened by the Soviet Union on the north, and trod the way towards concluding with Nazi Germany a pact aimed at the Soviet Union. Once it concluded the Anti-Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany in November, 1936, Japan tried to increase its allies against its supposed enemy, the Soviet Union. (76) So far as such a policy of Japan was a product of power-political calculation in terms of promoting Japan’s own interests in East Asia, the western neighbours of the Soviet Union did not easily responded to it.

According to a telegram of May 11, 1938, sent by Sako, the Japanese Ambassador in Warsaw, Lieutenant General Shigeru Sawada, Japanese Military Attache, at one time showed a draft for the Japanese-Polish Anti-Comintern Pact to the head of the Second Bureau of the Polish General Staff, and asked for a comment. The latter, however, requested the former to wait for a time because he did not think it opportune to conclude any such pact at that moment. Poland would not go beyond “actual cooperation,” such as the exchange of intelligence between diplomats or the contact between military officers, for instance, a joint meeting on strategic research for an imagined war against the Soviet Union. (77 ) It was evident even to the eyes of Japanese diplomats and military attaches that the countries on the Baltic coast north of Poland pursued the policy of neutralism for fear of being involved in the coming European war, especially in a military conflict between Germany and the Soviet Union. (78) It was further reported that there was a considerable difference of position even between those neutrality -directed countries, that is, between the Baltic States and the Scandinavian States, to which Finland belonged. (79) A Japanese diplomat in Helsinki observed that the violence of the Lapua Movement was frowned on by ordinary Finnish citizens, (80) and that the majority of the people wished to maintain democracy. (81) This indicated that the internal condition of Finland did not meet the Japanese expectation that the Finnish extreme right movement could serve the Northern neutality, (83) as well as its trend to keep away from the Polish Baltic policy, (84) was obvious. Under such circumstances, neither the Japanese Foreign Ministry (85) nor the General Staff (86) ever invited Finland to join the Anti-Comintern Pact. Holsti’s visit to Moscow in February of 1937 was described by Japanese diplomatic agencies abroad as an expression of Finland’s will to Northern neutrality. Charge d’Affaires Ichikawa in Helsinki had observed that the visit would be “of a passive character in the purpose, with merely an intention to normalize Finno-Soviet relations, which so far had been strained, “and that Finland is going to take this opportunity to have the Soviet Union understand that even in the event of war Finland will never take either side, but only keep strict neutrality, together with the Scandinavian States.” (87) In a conversation with Holsti at the end of the year 1937 Ichikawa felt his observation endorsed.(88)

Just after Holsti’s visit to Moscow took place, the Swedish Minister in the Soviet Union gave a Scandinavian account of the event to Mamoru Shigemitsu, the Japanese Ambassador to the Soviet Union. “Now that Japan and Germany have seemingly been brought closer together,” the Swedish Minister reportedly said, “the visit has been intended to reduce at any rate [Finland’s] friction with the Soviet Union.” Sweden, Denmark and Norway” had advised Finland to pay the visit from the standpoint that Finland lying between the Soviet Union and the Scandinavian States, would serve the latter’s interest through the effort to avoid involvement in East European conflicts.” (89) On Holsti’s return from Moscow, the Finnish Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Kivikoski, told Ichikawa: “The recent visit amounted to no more than an exchange of opinion about various questions pending between the two countries and the explanation of our peace policy. No new agreement has been concluded.” (90)

The nucleus of the Finnish rapprochement toward Scandinavian neutrals was the joint remilitarization of the Aland Island’s, to which the Japanese Legation in Helsinki had paid attention since the spring of 1938.91) In view of the rumour that Holsti’s visit to Stockholm on his way back from the Copenhagen Conference did bear on the Aland question, Yujiro Sugishita, the Japanese Minister in Finland, had his staff member make inquiries. The head of the Political Department of the Finnish Foreign Ministry affirmed the rumour: “The Finnish and Swedish Foreign Ministers have discussed how to maintain the pact of the demilitarization of the Aland Islands under the present uneasy European situation.” (92) In a telegram sent around that time Sugishita gave a penetrating observation of his own (93): ” ….. To keep its right flank safe, Germany most hopes for the neutrality of Scandinavian States in the event of war against the Soviet Union. At the same time Germany has grave concern about the Aland Islands in view of their geographical position and military significance – on the same islands there are at present even two airfields-, because, in the event of war, Germany must secure the route for transporting the iron of Middle and Northern Swedish harbors in the Gulf of Bothnia.”

General Kazushige (Issei) Ugaki (1868-1956) served as Minister of War, Governor General of Korea and Foreign Minister at various times

On the other hand, Foreign Minister Issei Ugaki (ed. General Kazushige (Issei) Ugaki ) sent an interesting piece of information in a telegram of August 10 to the Legation in Finland. On April 28, the Tokyo asahi shinbun had published an article entitled “Finland’s rapprochement toward Germany,” to the effect that Finland had proposed to leave the Aland Islands to German use for military purposes. On May 6, however, the Finnish Minister in Tokyo called on Inoue, Head of the Department of the European and Asiatic Affairs, to point out that the report had no foundation. A Japanese document describes Minister Valvanne’s conversation as follows: “[Valvanne said] The maintenance of neutrality of the Aland Islands was indispensable to Finland in order not to be involved in a war. For the sake of the maintenance of this very neutrality, the armament of the same Islands had been regarded as essential.Therefore, on the basis of the Swedish proposition the matter had been under consideration by the Finnish and Swedish Governments. He made the assurance, however, that any idea of remilitarization undertaken by Germany had never come into question.” (94)

At the beginning of January, 1939, an agreement was reached on the remilitarization of the Aland Islands between the Finnish and Swedish Governments, which then turned to the signatories of the Aland Convention of 192] for consent. On March 30, the Finnish Minister in Warsaw called on Japanese Ambassador Sako to tell that all the signatories except for Germany and Italy had consented to the remilitarization of the Aland Islands. The reason for the delay of the German and Italian replies was unknown, but “irrespective of their replies, the construction work will be undertaken according to the program. As this proves, the rumour that the remilitarization of the Aland Islands has been instigated by Germany is a false interpretation based on Soviet propaganda.” (95) The position of Germany was explained to Sugishita by Blucher, the German Minister in Finland. “While the Aland Islands being under the control of small neutral states meet the German interest, Soviet control of the same Islands in time of war is not what Germany hopes for. It follows from this that Germany agrees to the said remilitarization.” Since it did not wish to collaborate with the League of Nations, Germany had delayed its official answer. (96)

Soviet delegation on the way to the Naval Conference in Geneva in May 1927. On the left Boris Shtein and on the right Grigory Sokolnikov. From 1932 to 1934 Shtein was an ambassador in Finland

Therefore, the question of the remilitarization of the Aland Islands centered on the Soviet attitude, but the Japanese Legation in Finland had got little information about the secret negotiations that had been carried out between the Soviet and Finnish Governments since the spring of 1938. In a telegram of March 31, 1939, (97) Minister Sugishita reported as follows. According to the information obtained “from the Italian Minister here and other sources,” Boris Stein, the Soviet Ambassador to Italy, who had stayed in Finland since March 10, had proposed that (a) the Suursaari be ceded to the Soviet Union in return of the latter’s recognition of the remilitarization of the Aland Islands, and (b) in that case, the Soviet Union will not only respect and guarantee Finland’s neutrality, but will also sign an economic agreement. The Finnish Government, however, had given an outright denial. Hackzell, Foreign Minister at the time when Stein had been stationed in Helsinki, confidentially told Sugishita, “Stein has talked with different circles of this country about various political problems, which, however, are not what we can take up.” Hackzell, however, did not reveal the content of the talks.

Finnish Foreign Minister Eljas Erkko (1895-1965) – Erkko was the Finnish foreign minister between 1938 and 1939, as the Finns negotiated with the Soviet Union

In the period from the spring to the summer of 1939, the Soviet Union continued to oppose the Finnish and Swedish rearmament of the Aland Islands on the ground that it would only profit Germany, (98) while in the Anglo-French-Soviet negotiations it stuck to the demand that Finland be included in the countries to be guaranteed. The Finnish Foreign Minister Erkko told Sugishita on June 10: “(a) Finland has got a promise from the British Government to the effect that it would not discuss with the Soviet Government the problem of guaranteeing Finland. (b) The Soviet Government fears that an accomplished fact will be put before it with regard to the problem of the Aland Islands. At the same time it has demanded from Finland an actual inspection on the presumption that Finland must have already started to rearm the Alands. One cannot but say that such an attitude is really based upon its’ inferiority complex.’ Finland will explain to the SovietUnion how things are, but has no intention of negotiating with the Soviet Union over any conditions for the purpose of obtaining Soviet consent.” (99) In a telegram of July 21, Sugishita expressed his view, which is retrospectively interesting. In regard to Latvia and Estonia, Germany had reason in time of war to go for military bases there for the purpose of blockading the Kronstadt. In regard to Finland, however, it would remain satisfied so long as Finland stuck to neutrality and maintained the security of the Bothnian Bay through ensuring the defense of the Aland Islands. In contrast, the Soviet Union would act in advance to put Estonia and Latvia under its control, and at the same time to exert the military pressure upon Finland. Sugishita found here the reason for the Soviet opposition to the remilitarization of the Aland Islands. (100)

V. In the Whirlpool of the Second World War

Counsellor of state J.K. Paasikivi and his team arriving from Moscow for the first round of negotiations on 16 October 1939. From left, minister Aarno Yrjö-Koskinen, J.K. Paasikivi, chief of staff Johan Nykopp and colonel Aladár Paasonen.

In his research in the Archives of the Japanese Foreign Ministry this writer has found only one report giving an account of the Finno-Soviet negotiations in the autumn of 1939. It is a telegram of October 14 sent by the Japanese Minister in Helsinki, Sugishita Yujiro, which runs as follows: “This country seems to have mobilized six divisions in all. It is presumed here that an invasion of this country demands at least 18 Soviet divisions or three times the Finnish military power. The movements of the Soviet army have been watched ….. , but no special change has been reported ….. The cession of islands in the Gulf of Finland and a partial revision of the boundaries on the Karelian Ithmus with Ino being included in the Soviet territory seems to be anticipated by the general public here.” (101) In fact, Sugishita had sent many other reports, which may have been destroyed during or immediately after the Second World War. He confesses, however, that staff members of the Finnish Foreign Ministry, which had usually been frank with him, were now close-mouthed, and that Sugishita did not dare to ask too much either. (102)

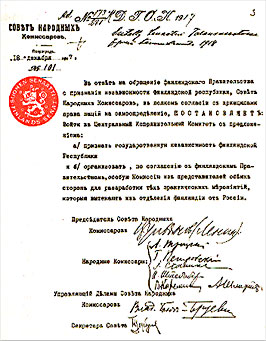

On December 18 (31), 1917, Lenin handed Svinhufvud, head of the Finnish government, the decree of the Council of People’s Commissars granting independence to Finland. The decree was endorsed by the All-Russia Central Executive Committee on December22, 1917 (January 4, 1918). Both Lenin and Stalin were signatories.

After the Soviet army began a mass-raid upon Finland on November 30, 1939, Japanese newspapers daily reported on the situation of the war and published articles extending sympathy to Finland. Japanese newspapermen had interviews with Finnish residents in Japan, including Mrs. Siiri Watanabe, the Finnish wife of a Japanese pastor. (103) On the “gloomy Independence Day” as it was called in a newspaper article, the Finnish Minister in Tokyo, Karl Gustaf Idman, broke the long silence to declare to Japanese newspapermen: “Lenin said in my presence that he recognized the independence of our country. Stalin, who is said to be his faithful successor, now menaces our independence. But the virile spirit of independence in our blood says thousand times ‘no’ to an idea of throwing ourselves at the Soviet’s feet. We will fight until our snow-white fatherland is soaked with blood.” (104) While Japanese newspapers condemned the Soviet conduct as “outright aggression,” they predicted that, judging from a comparison between the Soviet and Finnish national strengths, Finland would not be rescued even with the aid of Britain, France or the United States. “We rather set the question: in the likely event of a Soviet victory over Finland will the Soviet Union satisfy itself? Won’t it advance again elsewhere? Our attention should be directed to this.” (105)

While expressing “sympathy” for Finland, one Japanese newspaper made a comment which reflected the standpoint of Japan belonging to the Axis: “The tragedy of Finland is that it is looking to Britain, the United States and France for the help that will never come. ….. In short, the world is on the eve of the collapse of the old system. We only see the dynamic power destroying the old order and the throes of a new order about to be built.” (106) The Japanese Government, however, kept silence about the Finnish resistance to the Soviet attack. (107) At the outbreak of the Second World War in September, 1939, the Japanese Government had declared: “Faced by the outbreak of the present European War, our Empire will not intervene in it, but strive for a settlement of the China Incident [the Sino-Japanese War].” (108) And in fact it had maintained a neutral attitude toward the European conflict. In addition, Japan was in a position carefully to avoid making any provocation to the Soviet Union.

In addition, Japan was in a position carefully to avoid making any provocation to the Soviet Union. In the summer of 1939, Japan had suffered a military defeat at the Nomonhan Incident and then came the conclusion of the German-Soviet pact, which indicated an increase in Soviet pressure on Japan in East Asia. In order to “settle the China Incident,” Japan had no choice but to launch upon an improvement of its relations with the Soviet Union. In the middle of September, an agreement was reached on a truce to the Nomonhan Incident, which was followed by the establishment of a border demarcation commission. Negotiations for a fishery pact were also opened between Japan and the Soviet Union. (109)

According to Dr. Lintulahti, the Japanese Government, which had reacted without delay to the hope that Finland would win the fighting, was officially extremely cautious of taking a pro-Finnish attitude, which was reflected in an instruction sent to Shigenori Togo, Ambassador in Moscow, to the effect that he should not interfere in the question. (110) Being aware of the Foreign Ministry’s views that pro-Finnish activity was undesirable, Baron Mitsui, the president of the Japan-Finland Society, was afraid that an excessive expression of sympathy for Finland might have such an influence upon the Soviet Union as to trouble the Foreign Ministry. Mitsui was of the opinion that the aid to Finland should be confined to an assistance short of political activity, that is, assistance, for instance, to war orphans or war widows. He refrained from raising a fund openly under the auspices of the Society, but sent to the Finnish Red Cross a certain amount of money out of his own pocket. (111) Such being the case, the Japanese Minister in Helsinki was in a position to be a spectator throughout the period of the Winter War. (112 )

The Finnish Foreign Minister declared to Minister Sugishita that in view of the difference of military power between Finland and the Soviet Union, the former’s last resource was the support by the world public opinion, which could be expected only when Finland fought by fair means. The Finnish pride showed itself in one particular episode. A Japanese navy officer proposed that Soviet mines captured by the Finnish navy be sold to Japan, but it aroused indignation among Finnish officials, who asserted that Finland, the small power that it was, could not convert things of such a character into money. Nazi Germany took a cold attitude toward Finland, even taking sides politicallyvwith the Soviet Union. The Western Powers had neither the capability nor the intention to give effective aid to Finland. Sweden was afraid that it might be involved in international conflicts. Finland fought alone with its weapons and ammunition running out. At the time of the Nomonhan Incident, the General Staff of the Japanese Army had notified to the Finland side, through the Military Attache in Riga, Hiroshi Onouchi, that a semi-official Japanese company had been ready to export some weapons, but no answer had come from the latter. Under the desperate circumstances of the Winter War, however, the Finland side requested Onouchi through the Finnish Military Attache in Riga for the sale of the same weapons, but at this time the Japanese General Staff declined. (113)

In the latter part of January, 1940, a correspondent, named Kitano, for a Japanese newspaper, visited Finland to write to Japan about the city of Turku under air-raids, the Finnish Defense Corps, the spontaneous unity of the Finnish people, etc (114) Afterwards Japanese newspapers were for a time silent about the Finnish front, but toward the middle of February they resumed reports about the desperate fight of the Finnish army. In the middle of March, 14, one article, which was entitled “Repercussions of the Finno-Soviet truce,” read: “The Finn’s brave fighting for more than one hundred days….. should be remembered for many generations,” but, “A more urgent problem attracting our attention is the possible repercussions in the Far East of the Finno-Soviet truce,” (115) On March 13, the same newspaper published the following article, apparently reflecting the views of the Japanese Foreign Ministry:

Japanese Ambassador to Moscow (1938-1940) Shigenori Togo (1882-1950). His wife was German.Tōgō was adamantly against war with the United States and the other western powers

“The armistice agreement between the Soviet Union and Finland will have considerable influence upon the present situation of the European war in terms of an increase of the German and Soviet influence upon Northern countries. In the opinion of our Foreign Ministry, however, the truce will influence not only the European situation, but also the Far Eastern policies of Germany and the Soviet Union to a considerable extent. Especially the Soviet Union, having secured its borders, can now expand its influence in the Far East more freely than ever. Attention should be paid to what move the Soviet Union will make regarding the negotiations on pending questions between the Soviet Union and Japan.

Neither the negotiations on the organization of the border demarcation commission nor those for the essential treaty of fishery is going very well. The trade negotiations, which had been expected to make advance, have been tended to stagnate these days. The Foreign Ministry has turned its attention to next [Soviet] move.” In April, however, the Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tani, observed, ” ….. In view of its trend toward increasing friendship with Japan, the Soviet Union seemingly has a grand design for Europe. ….. In other words, for the purpose of realizing such a design, the Soviet Union seemingly wishes to secure peace in the east by acting diplomatically towards Japan. Both the Nomonhan problem and the problem of the exchange of prisoners have already been solved. Progress is being expected also regarding the problem of border demarcation, and then, the revision of the fishery treaty.” (116) Japan’s relations with Finland in the months preceding the Continuation War developed essentially within the framework of the former’s relations with the Soviet Union. For the purpose of stopping the Soviet aid to China, Japan decided, in May, 1940, on the policy of concluding a treaty of neutrality with the Soviet Union.

In June, the necessity of such a treaty increased. In embarking upon a new policy of expansion in the south, Japan now wished to ensure safety in the rear, as well as to check the British and American armed intervention. (117) On July 2, the Japanese Ambassador in the Soviet Union, Togo, proposed a treaty of neutrality to the Soviet Foreign Commissar, Vyacheslav M. Molotov, and, on August 14, the latter made a Counterproposal that the treaty of neutrality should essentially carry the character of a non-aggression treaty, demanding compensation for the involved danger of aggravating Soviet relations with China, Britain or the United States. (118) The newly appointed foreign minister, Yosuke Matsuoka, had entertained a grand design for a new world order. First, there should be an alliance between Japan, Germany and Italy. Then, the Soviet Union should be invited to form an entente with those three powers on the basis of divided spheres of influence. Great Britain and the United States would thus be restrained. For this purpose, Matsuoka intended to conclude a treaty of non-aggression with the Soviet Union through the agency of Germany.

Yōsuke Matsuoka (1880-1946), Foreign Minister from 1940-41. When the Pacific war broke out, Matsuoka professed, “Entering into the Tripartite Pact was the mistake of my life. Even now I still keenly feel it. Even my death won’t take away this feeling.”

In November, 1940, Hitler invited Molotov to Berlin and proposed an entente between the Four Powers, but on receipt of the answer in which the Soviet Union made no concession regarding its sphere of interest in Europe, he gave orders on December 18 for Operation” Barbarossa.” Matsuoka, who was unaware of this about-face in the German policy toward the Soviet Union, visited Germany and the Soviet Union in a period from March to April, 1941. The Soviet Union secured from Matsuoka a treaty of neutrality to prepare itself for the coming crisis of the International situation. (119) In the above negotiations Japan tried to have the Soviet Union recognize Japan’s sphere of interest in Asia in exchange for Japanese recognition of the Soviet sphere of influence in Europe. The Soviet Union, which considered the latter question already settled by the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Treaty, was unsusceptible to the Japanese proposal. In the above conversation of August 14, Togo contended, ” ….. If we confine our consideration within the scope of the East, Japan’s advantage may be larger. But when we bear in mind also the possible influence on Europe, the United States, etc., the treaty will bring the Soviet Union a large advantage, which could well be compared with our own. I feel pressed to retort, Haven’t you borne in mind only the situation of the East, without giving heed to Europe, the Near East and the United States?”

To this Molotov replied, “To my regret, I cannot agree to your opinion. In regard to the problems of Europe (including Southeastern Europe) and the Near East, you should give your attention to German-Soviet relations, which, as you know, is not merely based on the principle of non-aggression, but also will serve the solution of many individual questions, i. e., the questions of Poland, Bessarabia, Bukovina and the Baltic, and of course serve the solution of the Finnish question, too. Further, German-Soviet relations will not suffer any change at the conclusion of the Japanese-Soviet Neutrality Treaty.” (120) In “An Outline of the Adjustment of Japanese-Soviet Relations,” however, prepared on October 3 by the Foreign Ministry on the basis of the idea of the Four Power entente and also of the Soviet demand, the following sentence was inserted in the item 4, “The Soviet Union recognizes Manchukou, while Japan recognizes the recent fait accompli of the Soviet Union in Europe.”(121) The sentence had been prepared as an integral part of the Japanese-Soviet non-aggression Treaty.

Hachiro Arita (1884-1960), Foreign Minister a number of times, Arita was an opponent of the Tripartite Pact, and continually pushed for better relations with the United States. However, with the increasing power and influence of the military in Japanese politics, he was repeatedly forced to make compromises.