Käsikähmätaistelu (KKT) – Finnish Army Hand to Hand Combat Training

Straying away from logistics, economics and infrastructure briefly, there were other reasons why the Finnish Army emerged triumphant from the 1939-1940 Winter War. One of these was the emergence of a new doctrine placing an increased emphasis on hand-to-hand combat (Käsikähmätaistelu, or KKT) and on training soldiers in effective shoot-to-kill techniques.

The Army and the Suojeluskunta in particular encouraged its men (and women) to maximize their physical capabilities – Finland was also one of the very few countries in the world in the 1930’s whose Army encouraged and promulgated the learning of formal unarmed and armed martial arts combat techniques. From the early 1930’s on, a synthesis of techniques from the Japanese and Korean martial arts, primarily Judo, Ju-Jitsu and Karate but also from Tae Kwan Do and Aikido, together with knife and bayonet fighting techniques were taught within the Finnish Armed Forces. Conscripts got this in full measure from the mid-1930’s on. Combined with a backwoods penchant for savage brawling and knife-fighting, the Finnish soldier was not somebody you wanted to meet on a dark night in the woods. Or on any night for that matter.

Hand to Hand Combat and the Pyschology of Killing

The introduction of formal Hand to Hand Combat Training into the Finnish Armed Forces first occurred in the early 1930’s thanks to Gustaf Johannes Lindbergh (1888 – 1970), a Finn of Swedish origin from Turku. The scion of a Turku family heavily involved in shipping, Lindbergh had spent almost all of the 1920’s living in Japan where he worked for the family Shipping Company, learnt Japanese and became a student of the Japanese Martial Arts.

Gustaf Johannes Lindbergh – founder of KKT

A successful student of wrestling and boxing in Finland in his school days, where he had often represented his School and local City Teams in competitions, in Japan he primarily studied Karate, Judo and Ju-Jitsu, but also studied Aikido in it’s early from, Aiki-Jujutsu, under Morihei Ueshiba. An eclectic student and a quick learner, he seems also to have studied Tae-Kwan-Do under a Korean Sifu living in Japan, as well as various Japanese Sword and Weapon Fighting Techniques.

Lindberg returned to Finland in late 1929 and, having found work in Tampere, established his own Gym. A conservative, he found himself involved in factory politics in a city where many of the Workers belonged to the militant left-wing. Very quickly, he began to teach hand-to-hand combat techniques to fellow Conservatives and members of the Tampere Civil Guard who were often involved, despite the political rapprochement between the SDP and the Civil Guard, in street brawls and bar-fights with left-wingers.

No teetotaler himself, Lindbergh very quickly realized that the formalized wrestling, boxing and Japanese/Korean martial arts techniques he had studied had very little in common with real combat. As a result, working with some of his Gym members, he began developing a system of combat techniques for practical self-defense and offense in life threatening situations. His approach was to pare combat techniques down to the essentials, creating a reality based fighting system. On the streets, he continued to acquire hard won experience in a brutal school where losing meant a severe beating. This rapidly led him to a crucial understanding of the differences between sports fighting and street fighting.

Lindbergh training Suojeluskuntas men in street fighting techniques

Over the next couple of years, he developed his fundamental hand-to-hand combat principles: ‘use natural movements and reactions’ for defense, combined with an immediate and decisive counterattack. From this evolved the more refined theory of ‘simultaneous defense and attack’ while ‘never occupying two hands in the same defensive movement.’ The fighting technique he developed was certainly eclectic, incorporating techniques of wrestling, grappling, striking and kicking, with many elements borrowed from the Japanese and Korean Martial Arts he had studied. He rapidly became known for his schools extremely efficient and brutal counter-attacks.

Due to his Gym having a large number of Civil Guards as members, in particular many Officers (who could afford the membership fees), Lindbergh was invited in 1931 to become the Hand-to-Hand Combat Instructor and Chief Instructor of Physical Fitness for the Tampere Civil Guard units. In this capacity, between 1931 and 1933, he continued to develop and refine his hand-to-hand combat methods, and also began including physical endurance training, psychological techniques, the practical usage of cold steel weapons (fighting knives, hukari’s – the lethal two foot long Finnish Army machetes, entrenching tools, bayonets and rifles), knife and stick fighting techniques and aspects of close quarter combat such as sentry removal. By 1933 this had evolved into a system for military close-quarters combat, which he named, with a certain lack of originality, Käsikähmätaistelu, or KKT for short.

Following a demonstration for Marshal Mannerheim and Senior Officers of the Army in late 1933, organised by the Senior Officers of the Tampere Civil Guard, Mannerheim worked to ensure the promotion of Lindbergh to Chief Instructor of Physical Training and Unarmed Combat for the Finnish Army. Lindbergh moved into this position in mid-1934 and drove the rapid expansion of KKT training throughout the Finnish Army and into High Schools through the Military Cadet organisation. At the same time, he continued to work on the evolution of fighting techniques as well as the psychological aspects of hand-to-hand combat training, emphasizing physical endurance and the ability to take physical punishment in combat without being unduly perturbed, elevating and strengthening the spirit, emphasizing threat neutralization, simultaneous defensive and offensive maneuvers and developing an always aggressive mindset.

Lindbergh demonstrating KKT techniques

Under his leadership, KKT became an essential part of training for all members of the Armed Forces, women included. KKT fostered an aggressive mindset and the training, particularly in the Army during the Basic and Advanced Training periods, was intense (and intensely physical). Many recruits later spoke of it as one of the highlights of their training and the occasional foreign observer found the displays they were given by skilled practitioners during the Winter War itself verging on the terrifying, particularly those involving fighting with the Finnish Army’s hukari’s, the Combat Issue Machetes and also with Entrenching Tools, each of which were more than capable of taking off a man’s head or a limb.

From 1934 to 1936, Lindbergh had also devoted considerable time, in conjunction with two psychologists who he had met through his gym, to the psychological aspects of combat. In his hand-to-hand combat training, Lindbergh had placed a great deal of emphasis on overcoming what he had seen initially as a reluctance to fight effectively. He had later come to see this as a generic phobic-level aversion to violence which he then trained his students to overcome. He theorized that this might also apply to soldiers and their willingness to kill and began, in conjunction with the two psychologists, a systematic study into the improvement of the effectiveness of soldiers in combat.

The involvement of Finnish volunteers in the Spanish Civil War gave Lindbergh a practical theater for his studies and for two years, he and the psychologists were attached for long periods to the Finnish Volunteer unit fighting with the Nationalists. During these studies, they determined that for many soldiers, despite having volunteered for combat, there was a deep seated aversion to actually killing the enemy, with only 20-25% of individual riflemen actually deliberately aiming at the enemy before firing (with non-Finns, it was generally around 15-20% – Lindbergh theorized that perhaps the difference was that many Finns were outdoors-men who hunted recreationally). While they were willing to die, they were not willing to kill. They also identified that there was no such problem with long distance weapons, where the enemy was out of sight and therefore de-personalized. Specialized weapons, such as a flame-thrower, were usually fired. Crew-served weapons, such as a machine gun, were almost always fired. And firing would increase greatly if a nearby leader demanded that the soldier fire. But when left to their own devices, the great majority of individual combatants appeared unable or unwilling to deliberately kill.

KKT came to include weapons training, including knife fighting

In addition, they identified a number of physiological responses to combat involving vaso-constriction, tunnel vision and hyperventilating as well as “fight or flight” stress responses to the stimulus of combat. Studies Lindbergh carried out identified that this process was so intense that soldiers often suffered stress diarrhea with loss of control of urination and defecation being common. Lindbergh’s surveys identified a quarter of combat veterans admitting that they urinated in their pants in combat, and a quarter admitting that they defecated in their pants in combat. He also identified that there was a parasympathetic backlash that occurred as soon as the danger and the excitement of combat was over, taking the form of an incredibly powerful weariness and sleepiness on the part of the soldier. This seemed to occur as soon as the momentum of the attack was halted and the soldier briefly believed himself to be safe. During this period of vulnerability a counterattack by fresh troops could have an effect completely out of proportion to the number of troops attacking.

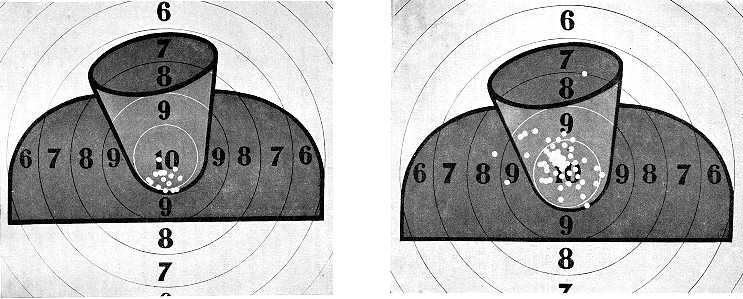

These were revolutionary insights into human nature and into a military problem – a 15-20% aiming and firing rate among riflemen is like a 15-20% literacy rate among librarians. Step by step through this period, Lindbergh worked from a military perspective to correct these problems as they were identified. And correct them he did. In the Winter War, the “deliberate aiming and firing” rate among riflemen in the Finnish Army was over 90 percent and there was no appreciable reluctance to kill enemy soldiers. Measures taken included replacing the old “bulls-eye” targets with man-shaped pop up targets that fell when hit and repetitious “snap-shooting” range training against the same man-shaped pop-up targets, creating a reflexive response pattern that became ingrained after constant repetition (constant repetition was heavily stressed as the key to success). Stimulus-response, stimulus-response, repeated hundreds of times proved to be a successful conditioner. After this training, when soldiers so-trained were in combat and somebody popped up with a gun, reflexively they shot and shot to kill without conscious volition (“..they shoot like automatons…” a foreign journalist wrote at the time, “…with unbelievable accuracy, aiming and shooting in an instant, killing with no visible emotion…..”).

Range targets

He also worked to understand the physiological responses to close-range interpersonal aggression. Tunnel vision, auditory exclusion, the loss of fine and complex motor control, irrational behavior, and the inability to think clearly were all observed as byproducts of combat stress. A key conclusion was that in many ways soldiers in combat were actually less capable than normal and conditioning was needed to overcome these physiological responses. Again, Lindbergh developed techniques to do just this, training soldiers to consciously adjust their physiological responses, largely through a combination of breathing exercises and “battle-conditioning” training under conditions of extreme stress and exertion simulating real combat as closely as possible.

By early 1938, he had proved his training and conditioning techniques to his and the Army’s satisfaction and these were rolled out in general and refresher training through 1938. With actual war looming in 1939, most soldiers received at least an abbreviated form of this training as part of mobilization refresher training in the Autumn of 1939. It was training that served the Army well in the Winter War, with the Finns achieving unprecedented effectiveness in the willingness of Finnish soldiers to aim to kill, shooting with an accuracy and effectiveness that was not reached in other Armed Forces until decades later. In this of course they were also aided by the outstanding individual firearms brought into service through the late 1930’s by the Finnish Armed Forces.

Suojeluskuntas range design resulted in increasingly skilled shooters

Those very very few foreign military observers who were permitted access to the front during the Winter War were in awe of the Finnish soldier’s military prowess. As one such observer was quoted as saying by a foreign (american) journalist “I don’t know if they terrify the Russians, but they sure do terrify me.” This particular observer had just witnessed an encounter engagement where an advancing Finnish Infantry Company of less than 100 men had wiped out a counter-attacking Russian Infantry unit of somewhere between 1,000 and 1,500 men in an engagement that lasted less than 5 minutes. (“In addition to the effective use of accompanying support weapons, the individual Finnish Soldiers immediately went to ground, making effective use of available cover and fired aimed shots at approximately 10 second intervals with outstanding accuracy,” he wrote in his report, “almost every shot seemed to find a target, the attacking Russian unit was wiped out to the last man. The Finns suffered 1 casualty, a light wound. They then resumed their advance.”)

A great deal of the credit for this must go to Lindbergh, the revolutionary insights into human nature that he came up with and the training techniques he devised to overcome these. Lindbergh continued as the Army’s Chief Instructor of Physical Training and Unarmed Combat until 1948, when he retired from the military, though he continued to supervise the instruction of KKT in both Finnish military and law-enforcement contexts, and in addition, worked indefatigably to refine, improve and adapt KKT to meet civilian needs.

Return to Table of Contents for “Punainen myrsky – valkoinen kuolema” (Red Storm, White Death)

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

3 Responses to Käsikähmätaistelu (KKT) and the Armeijan