The origins of the Lotta Svärd Yhdistys (Organisation) had its roots in the late 19th century. Finnish women first began to take part in patriotic activities during the turn of the 19th and the 20th centuries, a period of attempted Russian domination of Finnish nation-building which came to be known as the “years of oppression.” They founded their own women’s unit to help the Kagal, a Finnish secret society that opposed the oppressive government of Governor General Nikolai Bobrikov. The work of the Women’s Kagal consisted mainly of relaying the Kagal’s secret messages and collecting funds. The women also took part in supporting the Jaegers, the Finnish volunteers secretly sent to Germany during World War I to be trained as elite light infantry in preparation for a war against Russia. After the Jaegers returned to Finland, a large number of them took part in the Finnish wars as high-ranking officers. The Finnish women aided the Jaeger movement by supporting the Jaeger volunteers on their way to Germany. This patriotic activity among the women was widespread, but partly unorganized.

Vartija ja vankeja Fellmanin pellolla Lahdessa. Guards and prisoners at Felman field. You can see rows of people who had been arrested and brought to this field in Lahde. 20,000 reds were collected here in April and May of 1918. Most of the women and children were sent home while the men were sent to various prison camps. Here too in Lahde was where many women were executed

Lotta Svärd was a Finnish voluntary auxiliary paramilitary organisation for women, inarguably the most important voluntary organisation for women in Finnish history and was the worlds largest women’s national defence organisation. As with the Suojeluskunta, is a little difficult to describe correctly as there was no similar organisation in the USA, Britain of other Western European countries (again, as with the Suojeluskunta, similar organisations existed in the Baltic States and Scandanavia, but they were modeled on the Finnish organisation). While the USA had women in the military, as well as volunteer womens groups, and the British had women in the military (the Womans Land Army, the Womens Voluntary Service, the Auxilary Territorial Service, the Womens Auxilary Air Force being British examples) there is no easy direct comparison to the Lotta Svärd, which was very much an all-encompassing women’s organisation which was directly connected to the day to day needs of both the Finnish nation and the Finnish military. Members of the Lotta Svärd had a supreme sense of duty to the service of the Finnish nation and the pride in this overriding duty had always been a factor in the internal doctrine of the organization. The ideals of dedication, service, and pride in one’s nation were all important beliefs to Lotta members.

Finnish Red Guard Women, 1918

The origins of the Lotta Svärd lay in the Finnish Civil War and were rooted rooted in a long standing Finnish tradition of unofficial female groups that supported various civil organizations. As Finland prepared for independence, these organizations were a public service, providing food to volunteer fire departments and local governments. As the civil war approached, Finnish women activist organizations became more closely associated with the Suojeluskunta (the Finnish Civil Guard) organization. Under the umbrella of the Suojeluskunta, unofficial women’s organizations developed that provided food, clothing, and organized fund raising activities for the organization and their local community. As the Finnish Civil War erupted, the efforts of the Suojeluskunta were directed to support the Finnish White Army and the main purpose of the womens groups was initially to assist the Suojeluskunta with medical services and logistics. As the Civil War went on, activities for these women branched out to include additional tasks such as creating army equipment, cooking for soldiers in camps, and acting as telephone operators. In some areas, female volunteers were messengers and even acted as guards.

In the Civil War, some women on both sides wanted to take part in active combat. Throughout the areas controlled by the Reds, women’s guard units sprang up, comprising in all about 2000 armed women fighters. On the “white” side there were evidently also some women who desired do more that assist with medical services and logistics. An incipient debate on the matter in the Agrarian Party’s Ilkka newspaper in March 1918 was cut short by a prohibition against “White” female fighting units issued by the White commander-in-chief, General C.G.E. Mannerheim (1867–1951). Mannerheim wrote in an open letter “I expect help from Finland’s women in meeting the many urgent needs of the army, such as caring for the sick and wounded, manufacturing clothing, caring for the home and comforting those who have lost their loved ones. Fighting the war on the front, meanwhile, I hold to be the exclusive right and duty of the male.” Fifteen years later, Mannerheim would adjust this stance, as we will see.

Finnish Red Guard Women – 1918

The Red leaders also tried to prevent women from joining armed units, the main difference between the white and red leadership in this regard was that the Red leadership could not control what happened on the ground in their local communities. For example, in the city of Tampere, the local Social Democratic Women’s Association had nothing to do with the formation of local women’s Red Guards in March-April 1918 and probably even opposed them. According to historian Tuomas Hoppu, the women’s Red Guard in Tampere was not the result of any desire on part of the Red Guards to recruit women as reinforcements. The women’s guards were formed by independently acting women enthused by the revolution and inspired by the examples of women’s guards in revolutionary Russia as well as their own male relatives’ activities as guardsmen. Women were also attracted to the women’s guard by the relatively good pay in what was a time of high unemployment and scarcity.

That there was a strong cultural taboo against women taking up arms is evident, and it was a taboo that was expressed in executions and the intense vilification of the female red guardsmen as “bitch wolves” by the victorious Whites in 1918. In face of this taboo, it is remarkable how many women of the working classes evidently found the idea of female soldiering perfectly intelligible. On the white side, however, women obediently stayed within the sphere of action assigned to them by the military – although it is also significant that Mannerheim felt he had to order them to do so. The spontaneity and scope of the White women’s auxiliary activities in the combat zones show that the “white” women did not regard the war as only men’s business, in which they had no part or share, but as a joint venture where men and women had different tasks to fulfil but in which women actively participated.

Verna Erikson, a young student, was a Helsinki White Guard.

Verna Erikson, a young student, was a Helsinki White Guard. This image became a popular iconic photo, a sexualizing of female resistance. The photo was originally published on the front cover of the Suomen Kuva Lehti (Finnish Photo Magazine) in June 1918, just shortly after the civil war ended. Although there are photos of white women of the civil war time, they were not the ones collected. Rather, because Mannerheim frowned on women carrying guns, images of mother or grandmother in active resistance were put in the bottom of the drawer. Except for this photo of Verna. It has lived on, although she apparently died of cancer shortly after posing for this photo.

After the end of the Civil War, the Lotta Svärd emerged as a separate organisation. The name comes from a poem by Johan Ludvig Runeberg, part of a large and famous Finnish book written in poetic form, “Vänrikki Stoolin Tarinat” (The Tales of Ensign Stål), the poem described a fictional woman named Lotta Svärd. According to the poem, a Finnish soldier, Private Svärd, went to fight in the Finnish War and took his wife, Lotta, along with him where she sold the soldiers drinks and boosted their morale. Private Svärd was killed in battle, but his wife remained on the battlefield, taking care of wounded soldiers.

Private Svärd went to fight in the Finnish War and took his wife, Lotta, along with him

The name was first brought up by Marshal Mannerheim in a speech given on May 16, 1918 and in August of 1919, von Essen, the Commander-in-Chief of the Suojeluskunta at the time, used the term “Lotta Svärd” to describe the various womens volunteer organizations in his writings. This term caught on with the different organizations and soon many carried the name Lotta Svärd, with the first known organisation to use the name Lotta Svärd being the Lotta Svärd of Riihimäki, founded on November 11, 1918 (although another source states November 19, 1918).

On January 23, 1919 the Lotta-Svärd Chapter Nr. 1 (Lotta Svärd – Osasto No. 1 / Lotta Svärd: Division 1) was founded in Helsinki. This was a Swedish-speaking chapter and its rules served as a model when more chapters were founded in other parts of the country. The name Lotta Svärd started turning up more frequently in the associations’ names, and inquiries about the rules and founding proceedings were sent to the leaders of the Suojeluskuntas. The commander of the Suojeluskunta, Lieutenant Colonel Georg Didrik von Essen, issued an order on August 29 1919 that Lotta-Svärd Chapters should be founded in conjunction with Suojeluskunta Chapters and this also happened over the period 1919-20. By the end of 1919 there were over 200 independent, more or less organized Lotta-Svärd chapters in Finland. However, without common rules cooperation was difficult and caused confusion. As the number of the Lotta Svärd associations and the workload caused by it in the Suojeluskuntas Headquarters quickly grew, it became apparent that some sort of central management had to be established to take care of the things concerning Lotta Svärd. The decision to establish a national Lotta Svärd organization was finally made by the Sk.Y on May 11, 1920. As a consequence the national Lotta-Svärd organisation was founded in May 1920 and, while the date of the Lotta Svärd Association’s (Lotta Svärd Yhdistys) establishment is unclear, it was added to the official registry on 9 September 1920. At the founding meeting common rules were presented and approved. The rules had been made by a committee chaired by Helmi Arneberg-Pentti and also approved by the von Essen as Commander-in-Chief of the Suojeluskunta.

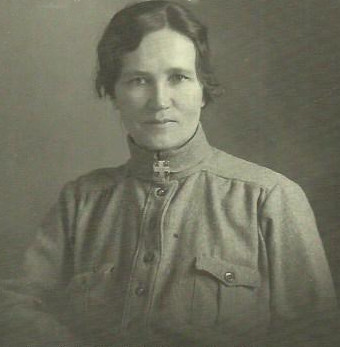

Lottakenraali Fanny Luukkonen (1882-1947), chairwoman of the organization from 1929 to 1944

Greta Krohn was appointed as the first national head of the Lotta Svärd Yhdistys on Jan 20, 1921. The first members of the board of management were Dagmar von Essen, Ruth Serlacius, Maja Ahlberg, Suoma af Hällström, Siiri Bäckström and Lolan Vasström. Substitutes were Greta Silvenius and Karin Herliz. Mrs Krohn was however relieved of her duties by von Essen early on as apparently she was making too many decisions on her own. On October 10 1921 the new Suojeluskunta Commander-in-Chief Lauri Malmberg appointed Helmi Arneberg-Pentti as the new leader of the Lotta Svärd Yhdistys, she however resigned in 1922 and was replaced by Dagmar von Essen. Dagmar von Essen was followed in 1924 by Tyyne Söderström who held the post until 1929, when Suojeluskunta Commander-in-Chief Malmberg appointed Fanni Luukkonen (a teacher) who would lead the organisation until the end of WW2.

In the founding charter, the Mission of the Lotta Svärd Yhdistys was stated as “The Mission of the Lotta Svärd organisation is to awaken and strengthen the Suojeluskunta-idea and advise the Suojeluskunta-organisation to protect creed, home and fatherland. The Lotta Svärd organisation will implement this by:

- Acting to increase the nations will to defend and to uplift the moral condition of the Suojeluskuntas;

- Assisting with the medical functions of the Suojeluskuntas

- Assisting with the provisioning of the Suojeluskuntas

- Assisting with fund-raising for the Suojeluskuntas

- Assisting with office functions for the Suojeluskuntas and gathering funds for financing its own activities and for the use of the Suojeluskunta-organisation.

Apart from assisting the Suojeluskunta, the Lotta Svärd Yhdistys role expanded in the 1920’s to include helping civilians through charity work. As national defence planning became more thoroughly organized and integrated through the 1930’s, the Lotta Svärd Yhdistys took on additional roles and responsibilities, as we will see later in this Post. Suffice it to say at this stage that the Lottas were key in altering the viewpoint of a very male-dominated society as the members of the Lotta Svärd proved that a woman’s role was important to the survival of the Finnish nation. The members of the Lotta Svärd served the Finnish nation as they felt it was their calling, and with pride they took on the duties that needed to be done for Finland to survive. There were many Finnish soldiers who called the members of the Lotta Svärd angels and these angels shone when their nation called on them in the hour of greatest need.

Lotta Svärd unit organisation

Structurally, the Lotta Svärd Yhdistys was organized similarly to the Suojeluskunta, with a Central Board, District Boards, Local Units and Village Sections, largely paralleling the Suojeluskunta organisation. Within this overall structure, the organisation was strictly divided into branches that were defined by the type of work done by the volunteers and in which new Lottas were placed according to their skills and education. This guaranteed an efficient way of working in both war and peace. At first various names were given to the branches but eventually they were called Medical, Catering and Supplies. As the organisation grew and new tasks were received, and as the situation changed during the wars, the division into branches and their tasks was modified to better fit their purposes.

The Lotta Svärd organization was closely connected to the operations of the Suojeluskuntas on all levels. This benefited both parties. The Suojeluskuntas needed the help and support of the Lotta Svärd organization in the areas which were best suited towards women and which most required workers. Similarly, the Lotta Svärd organization was often able to operate only because of the settings provided by the Suojeluskuntas s: office space and a supply of raw materials for the work of the provisioning and equipment divisions.

Before the founding of the national Lotta Svärd organization the standard requirements for new members were minimal. The only requirements in some local divisions were that the applicants be women over the age of eighteen who had “a good reputation”. Later, when the national organization was founded in 1920 and new rules were set, the requirements for new recruits were defined more closely. According to these new requirements all new applicants were accepted as long as they had a good reputation and their loyalty towards the legal social order could be trusted. The requirements did not set an age limit, but applicants under the age of eighteen needed to have permission from their guardians. Another regulation added the requirement that acting members who had committed themselves needed the permission of their husbands to be able to join the acting group. These requirements were later specified further in the rules made in 1921.

According to these rules, the local districts could accept any woman who was loyal to the Finnish Government, and who had the recommendation of two well-known and trustworthy people. In the 1930s the organization started putting new applicants on probation for a period of 3-12 months before they could be accepted as members. During the probation new applicants were educated in the work of the members and the principles of the organization. At the end of the probation period the applicants were given a test; those who passed it were accepted as new members. These requirements were followed until 1943, when the growing need for new recruits forced the management to start accepting new members on lesser grounds.

Lottas chose to take part in the organization’s work out of their own will. Their only motivation was their sense of duty and the fact that they wanted to do their own part in order to help their country survive the trials of war. Their work was both voluntary and largely unpaid; it was not until December 1939 that the Ministry of Defense decided to start supplying the acting Lottas with a small daily allowance.

Membership Categories were initially:

- Acting Lotta: Women were now trained to perform additional tasks beyond nursing and provisions, including air surveillance and signaling. This group was divided into categories according to where they were located.

- Supplies Lotta: Other active members of Lotta Svärd who worked in their assigned sections.

- Supporting members: They paid the membership fee, but didn’t actively work in Lotta Svärd Association. They also didn’t have the right to vote or be candidates in its elections (unlike other members).

In 1937, these categories were expanded.

- Acting Lotta: They were now divided into sub-categories, depending on whether they served in their home area or outside it.

- Reserve Lotta: They had similar training as Acting Lottas, but they had no orders for serving in any specific place. They functioned as reserves, and could be called upon to reinforce or replace Acting Lottas. They were also divided into sub-categories, which were determined by whether they served in their home area or outside of it.

- Supplies Lotta A: In mobilization, they would be called to serve in a task or profession that they had been trained for.

- Supplies Lotta B: All other Lottas not defined in the categories above.

To become a member of the Lotta Svärd, applicants needed two well-known and trustworthy persons to recommend them. The board of the local unit evaluated the applications and accepted new members. Upon acceptance, members took a pledge to the organization.

The Lotta-pledge -1921

“I [first name surname] pledge with my word of honor, that I will honestly and according to my conscience assist the Suojeluskunta in defending creed, home and fatherland. And I promise that I won’t give up working in the Lotta Svärd Association, until one month has passed from me verifiably informing the Local Board of my desire to resign from the Association. “

Lottas giving their Lotta Promise in a church in Turku

Lotta Svärd Etiquette and Behavior

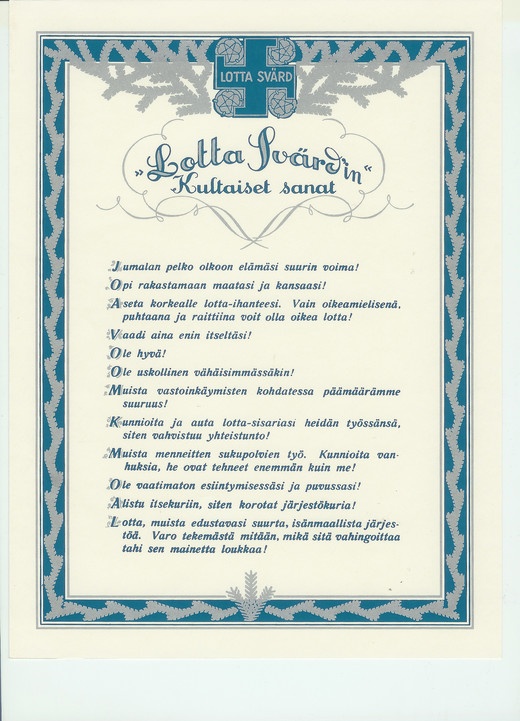

Lotta Svärd Golden Words

According to the rules, the purpose of the Lotta Svärd organization was to invoke and strengthen the ideology of the Suojeluskuntas and to aid the Suojeluskuntas in protecting religion, home and country. The organization carried out its purpose by attempting to raise the people’s morale and will for national defense and also by working for national defense in various fields of activity. At the same time the organization aimed to raise Finnish women to be model citizens. A Finnish woman was supposed to be patriotic, self-sacrificing, brave, enduring, responsible and skilled. The organization’s ideology was based on Christianity, morality and patriotism, which was also engraved in the organization’s Golden Words, which were an essential part in the crystallization of the “Lotta spirit”.

The Golden Words were as follows:

- May the fear of God be the greatest strength in your life!

- Learn to love your country and your people!

- Value your Lotta ideals. Only when you are righteous, pure and sober can you be a true Lotta!

- Always demand the most from yourself!

- Be good!

- Be loyal even in the smallest things!

- When you encounter misfortune, remember the greatness of our goal!

- Respect your Lotta sisters and aid them in their work, thus you can strengthen the feeling of unity!

- Remember the work of the past generations. Respect your elders, for they have done more than us!

- Be modest in the way you behave and dress!

- Submit to self-discipline in order to raise the discipline of the organization!

- Lotta, remember that you represent a great, patriotic organization. Be wary of doing anything that may hurt it or damage its reputation!

But despite everything, romance flourished. Boys will be boys and Girls will be girls….

Lottas were expected to act in a virtuous way and avoid causing disapproval in any way. During wartime the clothing and etiquette rules were slackened somewhat. In warm weather, Lottas were allowed to open the two top buttons of their shirt and roll up their sleeves (which then could be attached to shoulder buttons). During wartime, critics within the organization claimed that many of the newer members who had joined in the last half of the 1930s lacked the high ideological standards of the earlier members. In a way the critics were correct, the organization received huge number of new members in a short time, and many of the newer members, coming as they did from families with SDP backgrounds, did not share the same beliefs as those members from “White” families.

The Lotta Svärd disciplinary regulations and the Golden Words obliged every Lotta to remember that they represented the whole organization. The discipline was absolute concerning the use of alcohol and tobacco: the organization forbade Lottas from using alcohol while on duty and while wearing the Lotta uniform, and smoking was not allowed in public. Lottas were also not allowed to use make-up while wearing their uniforms, and the use of jewelry was restricted so that only wristwatches and wedding and engagement rings could be used. Improper behavior could result in disciplinary measures or in the worst case expulsion from the organization.

Although the rules were usually strictly followed, some problems did emerge. The tense wartime atmosphere gave rise to all sorts of negative rumors about the behavior of Lottas on the front lines. There were of course some actual cases of rule-breaking, for example drinking or smoking in public, but in most cases the rumors proved to be baseless. Additionally, most of the rule-breakers were young women who had only recently been accepted into the organization during a time of great need for new recruits, and who had not had time to adopt the organization’s ideals. All in all, only 346 Lottas, comprising only 0.38% of the 232,000 members, were ever expelled from the organization for breaking the code of behavior.

The typical punishments that Lotta Svärd used for members that broke the rules were transfer or being sent back home. The most severe punishment was sending the member back home to her own Lotta Svärd local unit, which could issue an official warning, or suggest the member resign. During the Winter War some 130,000 Field Lottas served, and only 346 received suggestions to resign, or were suspended.

The Lotta Svärd Branchs

Lotta Svärd Medical Branch

At first the tasks given to the Medical Branch were basically the same as during the Civil war, i.e. first aid and assisting the Suojeluskuntas. New orders in 1922 however said that every Suojeluskunta chapter, company and division should have a certain number of Medical Lottas to perform duties at the front (treating and transporting wounded and sick soldiers, arranging first aid stations) as well as on the home front with similar and other medical tasks.

Lottas on a Medical Training Course

The greatest undertaking of the Medical Branch was however the establishment, equipping and staffing of fully equipped 250 bed Mobile Field Hospitals, of which there were eight by 1933 and some ninety by 1939, fully staffed by Lotta Svärd-trained Nurses, Medical Assistants plus ancillary personnel (cleaners, cooks, laundry personnel, administrative, etc). All the equipment for these Mobile Field Hospitals was funded by Lotta Svärd fund-raising through the 1930’s and it was a gargantuan national undertaking by the organisation that went on year after year – in fact, it was the organizations largest effort – but the end result was that when the Winter War broke out, almost every Regimental Combat Group in the Suomen Maavoimat was equipped with a Mobile Field Hospital. At the same time it was also the first measure of support which was primarily meant to help the National Defense and not the Suojeluskuntas, which the Lotta Svärd organization had been firmly supporting up to that point.

While the Field Hospitals were created and largely staffed by the Lotta Svärd, they were placed under Maavoimat Command from 1935 on, as the Lotta Svärd Yhdistys became more closely integrated into the overall defence organisation. Lotta Svärd Medical Branch personnel were assigned Maavoimat ranks and, on mobilization, became part of the Maavoimat. Annual Regimental exercises from 1936 on included Lotta Svärd Medical Branch personnel and the Mobile Field Hospitals. On the outbreak of the Winter War, the Lotta Svärd Medical Branch followed their mobilization plans and moved out with their assigned Regiments, staffing Field Hospitals, Hospital Trains and front-line First Aid Posts.

Front-line Lotta Medic – Winter War – taking a break at a frontline First Aid Post

In the early years of the Lotta Svärd Organization, members were not formally trained very well. The first courses started in the summer of 1922. Nursing training was in high demand, though teachers were scarce. Short medical courses, concentrating on gathering bandage material and medicines, were organized by doctors in the area. Until 1929, medical Lottas were trained at regional training centers on two-week-long basic courses or, if they were unable to attend these courses, they could receive the same training by taking evening classes for a longer period of time. Of course, such a short training was not enough to prepare the Lottas for actual medical care. Although they wanted to operate near the frontlines, the Suojeluskunta gave the impression that they would never be able to do so. However, in a presentation given in 1925 by Professor Hjalmar von Bonsdorff it was proposed that medical Lottas could work in field hospitals as nurses or their assistants if a war broke out. It also proposed that the training periods for medical Lottas should be lengthened to correspond to these tasks.

These guidelines were soon followed when a committee set up by the central board planned and organized six-month-long training periods for nursing assistants. These started in 1928 and proved to be highly effective. Numerous 6-month nursing courses were organized and by 1938 about 65 percent of Lottas belonging to the nursing section had participated in these courses. Even with the preparation that had gone on, there were not enough trained medical personnel and perhaps the single most important task of the Lotta Svärd Medical Branch was to train additional Lottas for duties at hospitals, helping the regular nurses, and also for duties in the hospital trains and front-line First Aid Posts. There was certainly no shortage of new volunteers for these tasks. The Lottas also took medical care of evacuees. Not all Lottas in the Medical Branch were available to serve in these militarized units for various reasons – but many of these personnel could and did carry out voluntary supportive work such as the manufacturing of bandages and other similar equipment.

Members of the Lotta Svärd Medical Branch

Other duties included by Medical Branch Lotta’s included the washing and mending of the clothes of wounded soldiers – their aim was that when someone left the hospital he would always have clean, neat, whole clothes. Not only humans were looked after by the Lottas, animals also needed caring for. Especially in the countryside animals were left without veterinary care during the War and it was left to the Lottas to look after them. Horses in particular had a hard time and received special care from trained Lottas.

The war brought some surprises, as the Medical Branch Lottas also had to perform some unexpected tasks such as writing letters home for soldiers that were not able to do it themselves, and be good listeners when someone wanted to talk to someone about their difficult experiences at the front (these tasks were often performed by the “Small-Lotta’s” (more on this Girl-Lotta organisation later). Lottas also delivered information regarding evacuees to their relatives in the army. Libraries were set up at hospitals, and entertainment arranged. The Medical Branch Lottas also took care of the canteens at hospitals. Some of the Lottas in the Medical division were called Blood Lottas, because they were responsible for transporting donated blood. Perhaps the toughest job was performed by the Lottas at the KEK centres were dead soldiers were washed, dressed and put in coffins before being sent home to their relatives.

Lotta Svärd Catering Branch

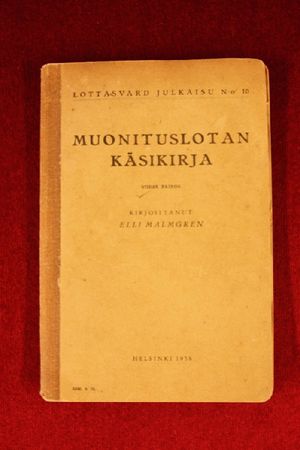

Elli Malmgrenin Muonituslotan käsikirja – The Catering Lotta’s Handbook by Elli Malmgren

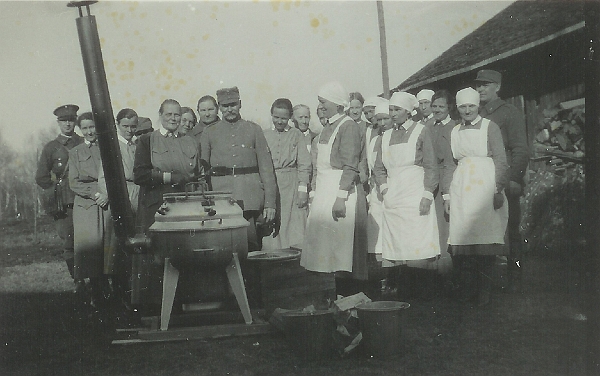

The Catering Branch was the biggest in the Lotta-Svärd Yhdistys (organisation), and it took care of food supply during Suojeluskunta manoeuvres, parades and during other public events – one that deserves mentioning is the 1938 celebration of the 20 year Anniversary of the end of the Civil War – some 900 Lottas and 120 field kitchens were involved in the festivities. The Catering Branch also assisted during large Army and Suojeluskunta manoeuvres. Over the years the activities of the Catering Branch became quite diverse, partly thanks to the book “Muonuttajien Ohjeet” published in 1926 and later additions to it. The “bible” for the Catering Branch was the Catering Lottas’ Handbook (Lotta-Svärd publication Nr 10) written by Elli Malmgren. Lotta-cafés were organized by the Catering Branch and held all over the country, with the income from the cafés being used to buy more equipment.

As we will see in a later Post looking at the construction of the fortifications on the Karelian Isthmus through the last half of the 1930’s, the Lotta-Svärd Catering Branch was responsible for the food supply to the volunteers working in Karelia building fortifications. From 1935 on, Catering Branch Units from all over Finland travelled to the Karelian Isthmus on a regular basis every summer to support the construction volunteers, with thousands of Lottas taking part. On the outbreak of the Winter War, Lotta-Svärd Catering Branch personnel staffed Field Kitchens for almost every unit in the Maavoimat down to the Company level and as with Medical Branch personnel, were integrated into the Maavoimat, assigned Maavoimat ranks and operated as part of the military units they were attached to. Many Lotta Catering Branch personnel operated Company Field Kitchens close to the front lines and, like all Lotta personnel operating as part of combat units, were armed with individual firearms. Many were involved in combat at the height of the Winter War, a not inconsiderable number died in action.

President Svinhufvud inspecting a Lotta Field Kitchen

One Lotta Catering Branch Field Kitchen Unit attached to an Infantry Battalion was even awarded the Mannerheim Cross (tragically, this was posthumous. Attacking Russian units in overwhelming strength had broken through the Finnish defence line in a surprise flanking move and were penetrating the Finnish rear area. The women and girls of the Field Kitchen Unit were all that stood between the attacking Russian regiment and a key crossroads. Caught by surprise, rather than running, the unit of young Lottas stood their ground and fought, catching the Russians by surprise and decimating the initial attackers with well-aimed fire from their Suomi SMG’s before going to ground and holding the Russians off until a scratch Finnish unit arrived to contain the breakthrough. Unfortunately, only half a dozen Lotta’s of the unit survived the initial attack and of these two later died from their wounds. The attacking Russian unit was wiped out to a man. “The Last Stand of Field Kitchen Unit #xxx” is covered in a later Post when we get to the actual fighting).

At the start of the Winter War the Lotta Catering Branch baked 200,000 kg of bread every day for the troops, this enormous task was organized through special Baking Units and local chapters worked shifts to maintain the supply. Commercial Bakeries, School and large farm kitchens were all used. Food was also organized for evacuees and other civilians affected by the war, and for Field and Army hospitals and hospital trains. It was a mammoth undertaking, and with the Lottas carrying out this work, large numbers of men were thereby available for front-line combat.

Lotta Field Kitchen in operation – this unit is from Oulo

Lotta Svärd Supplies Branch

Lotta Svärd Supplies Branch units at work

The roots of this branch can also be found in the 1918 Civil War. When the priest in Siikajoki, O.A. Salminen and his wife Maija learned about the outbreak of the Civil War, they organized knitting meetings for the women, and the response was good. Wool was collected and converted to mittens, socks and other winter clothing to be sent to the front. In the first years of the Lotta-Svärd organisation, the activities were similar; knitting, sewing and mending, mainly equipment and clothing for the Suojeluskunta and for the Lottas themselves. New gear was also acquired and some stored for (war)time use.

All uniforms, armbands and patches were made by the Lottas. Naturally they also took part in bookkeeping and other tasks related to Suojeluskunta equipment. In the 1920’s, members who belonged to the Supplies Branch received on-the-job training. In the 1930’s, training became more formalized as the Supplies Branch took on more and more responsibilities and became organized in a more military fashion. Training pamphlets were written, formal Courses were held and annual exercises were held in conjunction with the Suojeluskunta. The equipment section arranged courses on gathering materials and on creating supplies, uniforms and equipment such as webbing, magazine pouches and camoflauge suits, in some cases professional tailors or military tailors taught these courses.

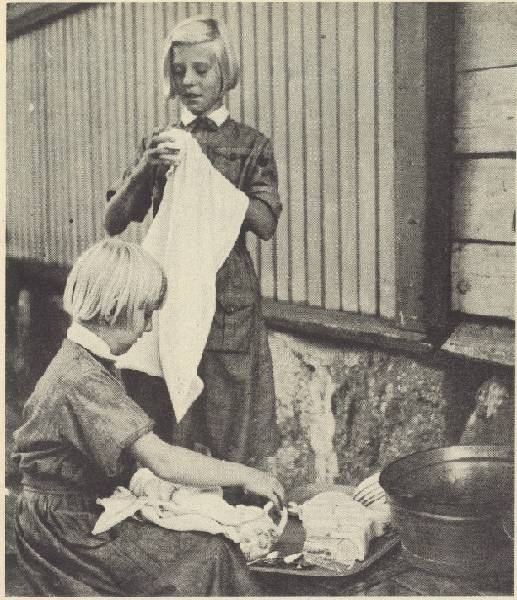

Snowsuits being sewed at a Repair Workshop

As part of the military restructuring of the 1930’s, the Lotta Svärd Supplies Branch took over all responsibility for the making of Uniforms and clothing for both the Suojeluskunta and the Army. Starting in the early 1930’s, they began making snow camouflage suits for the army and many more were made during the war.

Laundry was mainly washed by hand.

Being outside the strictly military chain of command prior to the Winter War, the Lotta’s were also more open to unconventional ideas and approaches and were also more interested in their menfolk’s comfort and well-being. This resulted in some unusual innovations, such as the mottled brown and green summer camouflage uniforms that were introduced in the late 1930’s and which proved highly effective in the months of summer combat in 1940. Thus the Lotta Svärd Supplies Branch was also responsible for the design and manufacture of the boots worn by Finnish soldiers – and the new 1937 issue boots proved far more comfortable and durable than the previous Army-issue boots. The Lotta Svärd Supplies Branch was also responsible for all military laundries, with Mobile Field Laundry Units established and railroad cars converted into mobile laundry facilities that could be moved closer to the front.

Lotta with Horse (the Finnish Army relied on thousands of horses for transport, these tied up a great number of personnel, by 1939 most of whom were Lottas)

The Suomen Maavoimat also used large numbers of horses for logistics and large numbers of personnel were needed for horse handling and care. As the Maavoimat was reorganized, wherever possible Lotta Svärd Supplies Branch were assigned to positions necessary for horse handling and care, again freeing up many thousands of men for combat roles. Likewise, in 1937, the bulk of rear-area Quartermaster positions were reassigned to Lotta Svärd Supplies Branch. And as more trucks became available through the 1930’s in the event of a Mobilization, plans called for Lotta Svärd Supplies Branch to supply the Drivers for these (as well as drivers for all remaining public transport – primarily trams and buses). In the 1920’s, this Branch consisted mainly of elder Lottas, who carried out their Lotta duties by doing handiwork; and it also had the smallest number of members. However, as the Branch took on added responsibilities, it acquired more and younger members.

Lotta Svärd Fundraising Branch

This branch collected funds and supplies for supporting the Lotta-Svärd and Suojeluskunta organisations. This was done through lotteries, soirees, different festivities and by selling magazines and badges. “Office” was added to the Branch’s name in 1925 in connection with updating of the organisation’s rules. The first courses on activities such as chemical warfare protection and mobilisation manoeuvres were organised in 1927. In 1932, the Branch was split into two, with the Lotta Svärd Fundraising Branch continuing to be responsible for all fund-raising, materials and social activities, the Office and Administration Branch taking responsibility for all administration-type activities and in 1937 the newly formed Lotta Svärd Guards Branch taking responsibility for more directly military-related activities.

Lotta Svärd Office and Administration Branch

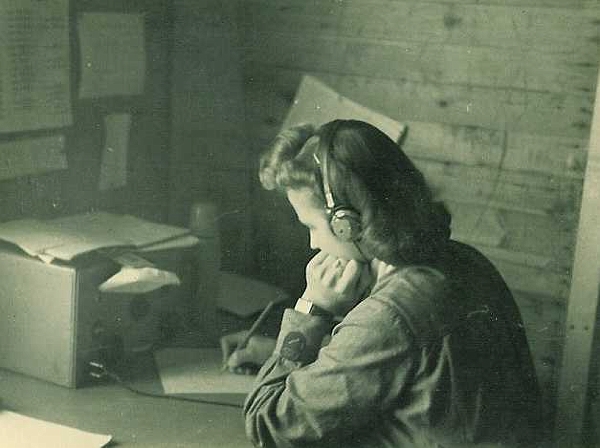

Lotta Radio Operator

From 1932 on, the Lotta Svärd Office and Administration Branch took responsibility for all administration-type activities. This Branch took care of Field Post Offices within the military, Communications (which included both telephone switch board operators, telegraph operators and radio operators – of which many were required), administration and office/typist jobs in the Suojeluskunta, Maavoimat, Ilmavoimat and Merivoimat as well as in their own offices (freeing large number of “manpower” for the front-line combat units).

Office and Administration Branch personnel also worked as translators, Meteorological Lottas carried out weather observations and prepared weather reports, there was also a separate unit within the Branch that took over responsibility for Mobilization Management from 1935 on. This was a crucial task, and one that we will examine in detail when we look at Mobilization Planning and preparation.

Lottas Censoring Soldiers Mail – photo courtesy of kevos4

Meterological Lottas at work

Lotta Svärd Guards Branch

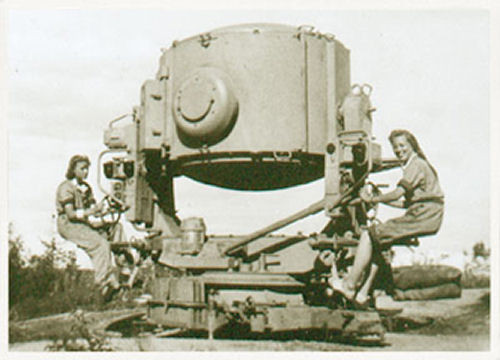

Lottas practicing sound ranging

Established in 1937, this was perhaps the most “combatant” of the Lotta Svärd Branches and was largely formed as a result of increasing pressure from young women who had completed their Military Cadet Training (more on this later) while at School, and who wanted to take a more “active” role in Finland’s defence than the traditional roles of the Lotta Svärd permitted. This pressure combined with the needs of the military for more manpower in front-line units and led directly to the formation of the Lotta Svärd Guards Branch. Units were created and personnel were assigned for Searchlight Batteries, Rear-area Anti-Aircraft Gun Batteries, Chemical Warfare Protection, Intelligence, conducted Air Surveillance, worked as Air Raid Wardens and Civil Defence personnel and conducted Sea Surveillance. Air surveillance courses and mobilization exercises started in 1932. Further courses were added in the late 1930s which included anti-chemical weapons training in 1936 and signal training in 1937.

Lotta Searchlight Unit in action

Lotta Sea Surveillance groups were formed in coastal areas, where they worked closely with the Suojeluskunta and with the Coastal Artillery, Coastal Jaegers and the Merivoimat (Navy). Sea Surveillance Lotta’s were trained in observation techniques, radio operating and artillery fire control. In the Winter War, it was the Air Surveillance Lottas who became the most well-known abroad. They were photogenic and easily spotted by foreign reporters, who were largely Helsinki based (with their movements outside Helsinki strictly limited and closely monitored due to well-founded fears of reporters also being Soviet spies). Beginning in early 1939, the Maavoimat also began to assign Lotta Svärd Guards Branch personnel, along with Boy and Girl Military Cadets of the 15-16 year old Class to the TJ-R150-24 (Taisteluajoneuvo 24x150mm Raketti) Rocket Launcher Battalions that were rapidly being formed. These units were leavened by a sprinkling of above-age soldiers, together with above-age NCO’s and Officers to provide command experience. All Lotta Svärd Guards Branch personnel were trained in the use of weapons and were armed for personal defence.

From 1936 on, the Ilmavoimat had there own Lotta Svärd Branch, which we will look at in detail along with the Ilmavoimat in the 1930’s. Suffice it to say at this stage that Ilmavoimat Lotta’s took on many roles within the Ilmavoimat.

Lotta Searchlight Unit posing for Foreign Photographers

Lotta Searchlight Units before the Winter War

Lotta Svärd Ilmavoimat Auxilary – Lotta Pilot ferrying newly-acquired aircraft from Britain to Finland

The history of the Small Lottas (Pikkulotta)

Small-Lottas at Summer Camp

Activities for girls were discussed was as early as in 1921 in a local meeting in the Mikkeli Lotta Svärd unit. Katri Langenkoski and Betty Tiusanen suggested that separate groups for 10-15 year old girls should be founded within the Lotta-Svärd organisation but received no response. When Langenkoski became a member of the central board in 1929, she again began working to promote this idea. The plan was presented by chairwoman Fanni Luukkonen at the annual meeting in 1931 where she suggested that the idea of Girl Lottas should be tested, a proposal which wone the board’s approval.

Small-Lottas – 1930

It is almost certain that the existence of the Soldier-Boy groups within the Suojeluskunta had inspired the Lottas. That same year the first rules for the Girl Lottas were approved, and leaders for the Girl Lotta work were also selected by the central board. Fanny Munck, head of the Supplies Branch, was given the task of designing a badge for the Small Lottas. Their uniform was basically the same as the normal Lotta dress. As an alternative to the normal cap, a blue beret with the local chapter’s insignia was agreed on. In 1933 an armband was approved as part of the uniform. Applicants were to be approved by the local chapter, girls between the age of eight and 16 and with their parents’ approval could apply. When the girls turned 17, they could (with the approval of the local Small Lotta leader) apply to be a “real” Lotta. The term “Small Lottas” was used up to 1943 when it was officially changed to “Girl Lottas”.

Small Lotta Activities

Small-Lottas on a navigation exercise

The activities of the Small Lottas were to learn to love their home, their parents, their faith, their fatherland and to respect their elders. To facilitate activities, the girls were divided into two separate age groups; 8-13 and 14-16 years old. On the schedule was singing, gymnastics, games, sports and useful skills such as sewing, cooking and first aid. In the Small Lotta Guide Book of 1938, it was emphasized that the younger girls should not take part in the older girls’ activities and that too much stress should not be put on anyone. Courses for Girl Lotta leaders were held at Tuusula with approximately 50 participants on every course. Trips and camps where the girls could meet friends of the same age from other parts of the country were very popular. Programmes at the camps consisted of both playing and games as well as activities such as orienteering. Competitions against the Boy-Soldiers were also arranged.

With the formation of the school-based Military Cadet organisation in 1932 (something we will cover later in this Post), the Small-Lotta organisation expanded to include the Girl-Cadets. As part of this move, in increasing emphasis was put on military-style training for the older girls. This included Military Drill, Physical Fitness, Rifle, Pistol and Machinegun shooting, Marksmanship, Small Unit Tactical Drills, a large dose of Outdoor Activity and Orienteering (both summer and winter) and, from about 1933-34 on, training in the new hand-to-hand combat technique of KäsiKähmä Taistelu” (or KKT as it was more widely referred to).

Small-Lottas assisting the Catering Branch – washing dishes

At the time, the decision to teach both Boy and Girl Cadets the same skills was somewhat controversial – the more conservatively minded wished to perpetuate the Lotta Svärd role in providing support to the military. This however conflicted with the ever-increasing demands on manpower of the Armed Forces as they expanded their capabilities through the 1930’s. Nationalism and the needs of the military conflicted with more traditional concepts of female roles, and it was the needs of the military that won out, as we will see.

The roles that women filled in the “mobilized” military continually expanded, and while they received more or less the same basic military training as men but at a less physically demanding level, women were never permitted to participate in front-line combat units. However, Girl-Cadet Training was the first step in preparing women for a greater role in the military and it was greeted with remarkable enthusiasm by many of the female students (but, it must be admitted, not by all….).

Cadet Training itself generally consisted of a half day per week, but for Secondary School Students, every second Saturday was generally also a Cadet Training Day, and from about 1935 on, Summer Camp Training for both Boy and Girl Cadets under the auspices of the military and the Suojeluskunta/ Lotta-Svärd organisations became more and more common. As we will see in a later post looking at the construction of defensive positons on the Karelian Isthmus, extended Summer Camps were also introduced from 1935 whereby Boy and Girl Cadet Volunteers who chose to could spend a major part of their summer holidays working on the preparation of the Karelian Isthmus Defences and receiving further military training at the same time.

Small-Lottas during the Winter War

Small-Lotta’s sewing for the Soldiers

The role of the Small-Lottas’ during the Winter War was generally to work as reliable and eager helpers. The older (14-16) girls were very useful in assisting their older “sisters” in the following areas:

Medical Branch: In the hospitals, the Small-Lottas worked in canteens, kitchens, laundries, worked as waitresses, helped feed wounded soldiers who were unable to feed themselves, acted as messengers, worked on switch boards, sat and talked to wounded soldiers, wrote letters for them, helped with sewing and ironing and manufactured bandages.

Catering Branch: The girls worked in canteens, cafeterias and military shops as well as working as dishwashers, cleaners and waiters, and assisted in baking and distributing bread and other food supplies for the army.

Small-Lottas operating a Telephone Switchboard

Supplies Branch: During the wars the girls manufactured a considerable amount of clothing and gear for the soldiers. E.g. gloves, socks, knee pads, helmet covers, ammo belts…The small Lottas also helped in mending and repairing clothes and gear.

Fundraising Branch: The Small-Lottas helped in fund raising, collected radio license fees, food, books bottles, scrap metal, wool and rags for use at the home- and real front. They arranged entertainment and soirees for evacuees and children.

Office Branch: The Small-Lottas helped in offices, switch boards and post offices. During the evacuation of civilians from front-line areas, the Small-Lotta’s filled a key role in the evacuation management, organizing billets for evacuees, escorting evacuees to their billets and acting as guides and liasions for evacuees. They also took a leading role in making flower arrangements for funerals and helped with the caring of grave yards. The older girl lottas also looked after the younger children.

Guards Branch: Older girl lottas (15-16 years class) participated in air and sea surveillance, crewed Searchlight Batteries and rear-area Anti-Aircraft Gun Batteries together with their older sisters and formed a major percentage of the personnel in the TJ-R150-24 (Taisteluajoneuvo 24x150mm Raketti) Rocket Launcher Battalions that were being established as an emergency measure from early 1939 on (a period when personnel shortages were acute as the Finnish military prepared against the ever-increasing threat of war from the Soviet Union).

Growth in Lotta Svärd Membership

In 1930, the Lotta Svärd organisation had 63,794 members. As with the Suojeluskunta, the reconciliation between the Social Democrats and the Sk-organisation in the early 1930’s also had its effect on the Lotta Svärd. Unlike the Sk-organisation where growth was almost non-existent in the period immediately after the reconciliation, the effects showed almost immediately with a substantial increase in the number of Lotta Svärd members as large numbers of women from Social Democratic families started to join. The growth in numbers of Lotta Svärd members from 1930 – 1939 was as follows:

1930: 63,794

1932: 74,842

1934: 86,022

1935: 122,344

1936: 165,623

1938: 172,755

1939: 242.045

Lotta Svärd Air Surveillance patrol

By 1939, with 242,000 volunteers, the Lotta Svärd was the largest womens voluntary defense organisation in the world, while the total population of Finland was less than four million. And by 1939 there were in addition 79,000 members in Lotta Svard girl-units (the Small-Lottas) and 42,000 suppporting members. Lotta units and personnel were allocated a variety of roles and responsibilities when the country was moved to a war footing. The real importance of the Lotta Svärd organisation during wartime was in the ability for its active members to free equal numbers of men from work, the homefront or in rear-area military support positions, making them available for front-line military use. Approximately 100,000 Lottas and some 30,000 older girl-Lottas were assigned to take over jobs from men, who were thereby freed up for military service. The numbers of men that were made available to the Finnish Field Army in this way was comparable several additional divisions. In addition, those Lottas and older Small-Lottas in the Guards Branch effectively filled a large number of rear-area combatant positions that would otherwise have needed men, freeing up even more men for front-line service.

Lotta Air Surveillance Post

As funding for the military increased along with economic growth through the 1930’s, and the size of the mobilized Armed Forces grew, manpower shortages were more and more evident. To cope with this, an ever-increasing role was allocated to women. Initially, the Lotta Svärd organisation was asked to perform some supporting work within Military Hospitals, Catering, Supplies and Administration. In 1934, with the Armed Forces Reorganisation legislation, a far wider range of rear area positions within the Army, Air Force and Navy were opened up to Lottas aged 18 and over. And once the door was opened, it proved impossible to close. Women became more and more indispensable to fill gaps in the military’s strength. And where there were personnel-availability gaps, it became more and more expedient to fill these with Lottas.

By the late 1930’s, Lottas were filling many rear-area combatant positions – and the formation in 1937 of that most “combatant” of the Lotta Svärd Branches, the Lotta Svärd Guards Branch, merely formalized what was already more a less a fait accompli. In 1937, this was legislatively systemized, with the military mobilization system being extended to include the Lottas, with approximately 130,000 Lotta and Small-Lotta members (almost half the Lottas overall strength) allocated to roles within the military where they manned supply and base depots, drove vehicles, filled rear area maintenance, office, signals and intelligence positions, served as ground crew in the airforce and filled base positions in the Navy, Air Force and Army. In addition, Lottas, Small-Lottas, Boy-Soldiers and overage Home Guard members manned rear-area anti-aircraft and searchlight batteries as well as air-raid warning posts. The partial (and it was an emergency measure) manning of the TJ-R150-24 (Taisteluajoneuvo 24x150mm Raketti) Rocket Launcher Battalions with Lottas was probably the peak of the militarisation of the Lottas. All Lotta personnel assigned to active service positions within the military were assigned weapons, as were many assigned to Home Front units, and by 1939 almost all younger Lottas had completed a short period (3 months) of military basic training.

Lotta Svärd- telephone exchange operator

Lotta Medic on the front-line treating a casualty – Spring 1940

But the most significant contribution made by the Lottas was the filling of a large number of medical positions within the Defence Forces. This was a war-time role that had been anticipated, planned and actively trained for almost from the start. The Medical Branch of the Lotta Svärd trained large number of Assistant Nurses and Medical Assistants. Training of assistant nurses was started in the 1920’s with two-week long courses. In 1929 the training program was made more effective and practical by lengthening the course to three weeks and adding a six month long practical training period in military hospitals. From 1932 on, these “3 weeks + 6 months” courses were ongoing in Viipuri, Tampere, Turku and Helsinki.

Lotta medic at work – Winter War

The medical branch of Lotta Svärd also gathered medical equipment: By the autumn of 1939 they had equipment for 90 well equipped 250-bed Field Hospitals with 22,500 beds ready for use, as well as having gathered equipment for numerous Battalion First Aid Posts and Casualty Clearing Stations. During the Winter War, approximately 60,000 Lotta Svard Nurses, Assistant Nurses, Medics and Medical Branch personnel worked in Army Field Hospitals, Military Hospitals and Hospital Trains, making up most of the rear-area medical strength.

The Lotta Svard organisation was also assigned responsibilty for handling food supplies for evacuated civilians and homefront troops, looking after families of reservists serving at the front and caring for evacuated civilians. Evacuation Management Sub-units were created from the mid-1930’s on for these purposes, with plans drawn up and training exercises carried out. These Evacuation Management sub-units were, from the mid-1930’s on, manned in large part by older Pikkulotta members serving under the command of older Lotta Svärd officers and NCO’s. The evacuation of Karelia in late 1939 was in large part managed by 13 and 14 year old girls who performed an amazing task coordinating and managing the movement, emergency accommodation and catering for thousands of evacuees.

Lotta-Svärd Equipment

The Lotta Uniform

The blue Lotta “hakaristi” with a heraldic rose in every corner

The first Lotta Svärd clothing regulations were issued in 1921 and comprised of a grey jacket, belt and skirt made from the same coarse fabric that the Suojeluskunta (the Finnish Civil Guard) used for their uniforms. This clothing, too warm and constrictive, was replaced two years later. In 1922 the Lotta dress code was approved nation-wide at the annual meeting. The dress was grey wool or cotton cloth, with loose white cotton collar and cuffs. The dress could not be shorter than 25cm from the ground (this was changed to 30 cm during the war).

Lotta Svärd uniform

Together with the dress, the Lotta-Svärd badge was worn on the collar. The badge was normally silver but later versions were only silvered. Winter trench coats retained the coarse cloth from the old uniforms, but the summer version was similar to a raincoat. Many items, such as the summer field caps were similar to those used by Suojeluskunta. Sports clothing (such as ski clothing) was not as formal and often included trousers instead of a skirt.

On the left arm, a cloth badge and band showed which branch the Lotta belonged to. On festive occasions, a band showing the district was also worn on the left arm. The Lotta cap was the same model as the Suojeluskunta cap and was made of a similar cloth to the dress. A cockade in the cap showed the colours of the Suojeluskunta District that the Lotta belonged to but later on the blue and white Army cockade was used. A white cotton apron was often used, especially by Catering and Medical Lottas. Other badges worn (on the left breast pocket) were the course star, badges received for 10 or 20 years in service, and different sport badges. Awards and medals were allowed to be worn on special occasions, and Medical Lottas with nurse training were allowed to wear the nurse’s badge of their organisation.

Lotta Svärd member with Lotta hakarisiti badge on collar

The rules for wearing Lotta clothing were quite strict:

- The only medals and insignias allowed with it were badges of honor plus of course the merit- and fitness-badges of the Lotta Svärd.

- No makeup was allowed and hair had to be kept inside the hat.

- Wedding rings and a watch were the only jewelry allowed.

- Drinking alcohol, smoking and immoral behavior were strictly forbidden while wearing Lotta clothing.

- Going to the frontline without permission was forbidden during combat.

Probably the most important, and at times controversial, insignia for the organization was Lotta-pin designed by Eric Vasstrom and introduced in 1922. The main motif of the pin was a blue “hakaristi” (Finnish variation of swastika) and with a heraldic rose in every corner. The probability of confusion increased greatly after the national-socialists gained power in Germany. The grey uniform-like clothing with a pin that had a swastika-like symbol caused foreigners to sometimes mistakenly think Lottas were connected with the German nazi-party.

Officially Lottas were also supposed to salute soldiers and each other with their own salute, in which the right hand was placed over the breast so its fingers extended all the way to point of left armpit. However, this salute was rarely used.

By the late 1930’s, with many Lottas serving near or even with front-line combat units, a rather more practical for combat use Lotta uniform had been introduced. In its essence, this was simply a men’s uniform tailored for women. By the end of the Winter War, almost all Active Service Lotta’s serving within the Army wore this uniform rather than the older style grey tunics.

Lotta Dish Sets

Lotta Cup and Saucer

Right from the start, the Lottas played an important role in catering at big public occasions and for parties, so large-scale porcelain services were needed. These were manufactured by Arabia between 1920 and 1944. Early services differ from later ones by being standard restaurant versions with the Lotta-Svärd logo added; these early versions are quite scarce today. At first, services were quite small but as the organisation grew in the 1930’s more and more types were added.

OTL, as the organisation was disbanded after WW2, the porcelain often came to a poor end. Services were donated to other organisations or split between members. Some were hidden in attics and other places to wait for better times. In the worst cases, everything was destroyed as happened in most of the bigger cities. Hence porcelain from smaller districts is more commonly found than those marked as being from city units. A lot of enamelled dishes, pans and pots were also manufactured and used, as they were cheap and sturdy in field use. These were also marked with the Lotta logo. Very few have survived since they were simply worn out and thrown away.

Lotta-Publications

The Lotta-Svärd organisation published a lot of printed material, most between the years 1930 and 1944. Three main groups of material are the Lotta Organisation’s magazines, public magazines and other material such as a Helsinki City Map.

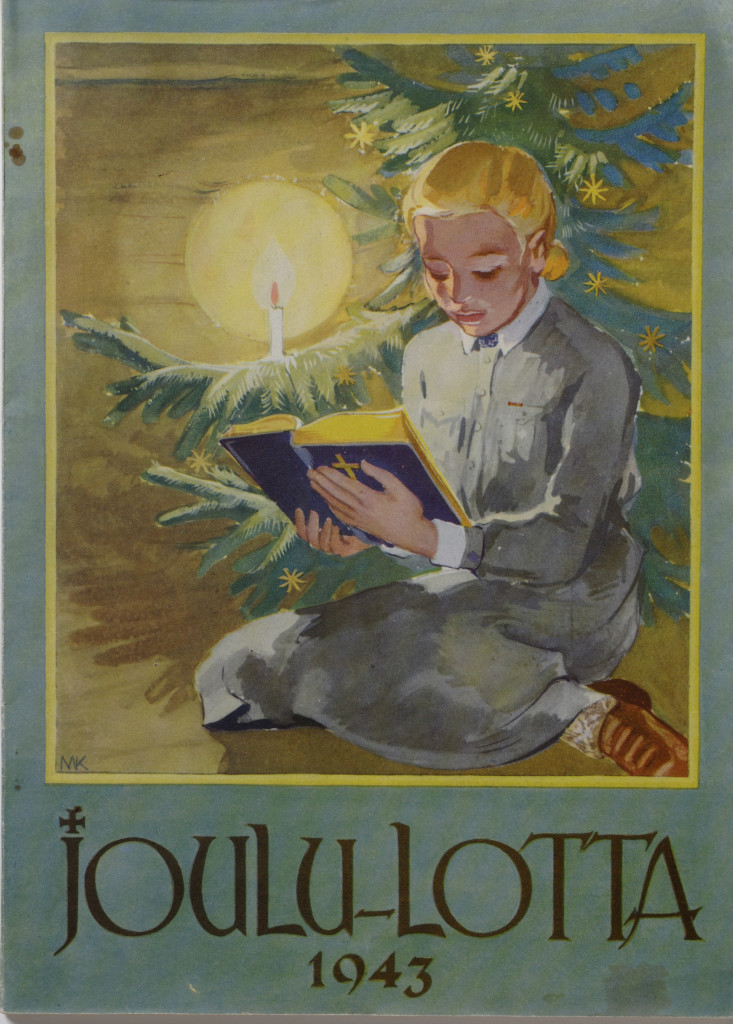

Christmas Lotta

The earliest publication was the Jul-Lotta Christmas magazine from 1922, this was in Swedish and made by Lolan Vasström of the Western Uusimaa district to raise funds. The following Christmas both Finnish and Swedish versions were published and all the funds earned were directed to the Lotta-Svärd central board to be used as they saw fit. The sales exceeded all expectations and the profit was over 72,000 finn marks. In 1922 Lolan Vasström transferred all publishing rights to the central board, the Magazine continued to be an excellent money maker and the profit was shared between the districts and local chapters. In 1930 and 1931 a childrens Christmas magazine named Lotan Joululahja was published but never gained much popularity.

1943 Lotta Christmas Magazine

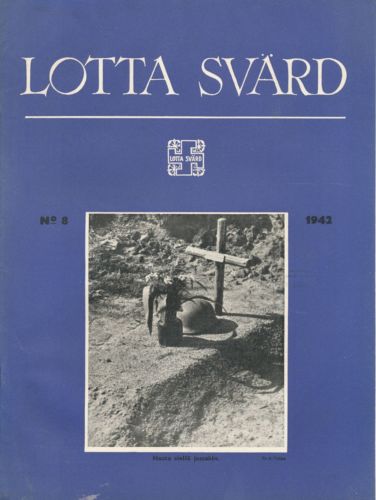

Lotta-Svärd magazine

The publishing of its own magazine was raised at the 1923 annual meeting but it did not happen until 1928 when Hilja Riipinen brought it up in a speech at the Vaasa Lotta. At this stage it was felt to be very important and the board was convinced, that same year the first issue was published. Hilja Riipinen was the editor of the magazine until 1936 when she was suceeded by Fanni Luukkonen. The magazine contained general information and stories written by the editors as well as pieces sent in by Lottas. From 1942 there was also a version in Swedish, and it was not just a translation but contained unique material in addition to material sourced from the Finnish version. The Swedish version is easily recognized by the yellow front page. Both versions of the magazine were published until the Lotta-Svärd organisation was disbanded.

Other publications

Hilja Riipinen, Lotta and author of “The White Book.” She was also a member of the Finnish Parliament from 1930-1939 (as an IKL MP from 1933-1939). She was nicknamed Hurja-Hilja (“Wild Hilja”) and was one of the most vehemently anti-communist IKL parliamentarians. Lapua Movement members said of her “There is only one man in Parliament and she is a woman”.

her the nickname Hurja-Hilja, or “Wild Hilja”

Not much written material was produced in the 1920’s, apart from the Christmas-Lotta Magazine – what was produced were mainly instructions and handbooks e.g for catering and medical Lottas. The handbook for catering was written by Elli Malmgren while the medical handbook was the result of teamwork. The most important Lotta book of the 1920’s was “The White Book” which contained stories of women’s roles in the Civil War. This was targeted at the general public and was the idea of Hilja Riipinen. The Suojeluskunta Song Book was another wide-spread publication.

In the 1930’s considerably more material was published. “The Golden Words of Lotta-Svärd” were the rules that every Lotta should obey, this was written by Luukkonen and Riipinen and given their graphical form by the artist Furuhjelm.The idea came from the “Commandments of the Fatherland” as published in the Porvoo community. Later the same kind of rules were written for the Small or Girl Lottas. More song booklets were published, pictorials showing the work of the Lotta organisation and later on a book on the subject of the Lottas in the WinterWwar. This book was also translated to Swedish and Hungarian (in 1942). A numbered print was also available. The next large work was a collection of frontline soldiers’ letters home. The book was titled “Unknown Finnish Soldier” and teacher Elsa Kaarlila had over 4000 letters to choose from. The profits from the book went to the care of war invalids and others suffering from the war.

In 1942 a book on Field Marshal Mannerheim was published, titled “Lottas and the History of our Fatherland 1: Mannerheim and my Fatherland” The book was later used for educational purposes. Another similar book was written for the Small Lottas – both books were written by Katri Laine. Other books aimed at the general public were “The Promise of the Young” “Women and the Mothers of Heroes” “The Direction and the Road”. Instruction books were published for the Office, Communications, Meteorological and Air Surveillance Lottas. Several song books were published in the 1940’s. In 1941 the magazine “The Field Lotta” first appeared, in that year with three issues and the following years eight issues. The magazine was intended for Lottas stationed away from home and contained greetings, messages and general organisational info and was distributed by the Lotta districts and border offices.

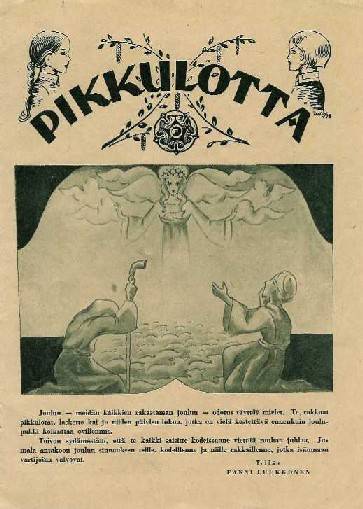

Small Lotta publications

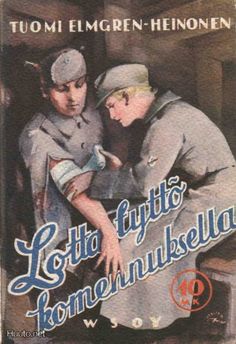

Pikkulotta (Small-Lotta) Magazine

As with the “real” Lottas, the Small Lottas also had their own magazine, this was first called Pikkulotta and later renamed Lottatyttö in 1943. First published in 1938, the aim was to produce a high quality, appealing but easily understandable magazine for the young. Puzzles, competitions and different stories were part of the content, together with poems and pictorials. A very popular reoccurring story was the one of the little girl Aune Orvokki, whose life the readers got to follow. Aune was the youngest daughter of a family in Kainuu whose father had recently died. Aune’s mother kept the readers informed of Aune’s life in letters, and the PikkuLottas sent Aune letters back with their greetings. Other publications were song books and handbooks, books on handicrafts and hobbies. In 1943 and 1944 a magazine for Girl-Lotta Leaders was published in both Finnish and Swedish.

OTL Note: The Abolition of the Lotta Svärd and the Years That Followed

OTL, the Continuation War ended on September 19th, 1944, when Finland signed an interim peace treaty with the Soviet Union. The 21st article of the treaty required Finland to abolish all “Hitler-minded (fascistic) political, military and military-oriented organizations as well as other organizations which practiced propaganda against the United Nations and especially the Soviet Union.” Although the Finnish government and the leaders of the defensive forces felt that the Civil Guards could not be considered to be a “Hitler-minded” organization, the treaty’s reference to military organizations gave reason to assume that the article’s main purpose was the abolition of the Civil Guards. As the Lotta Svärd organization was closely connected with the Civil Guards in its operations, the Lottas could also feel the same foreboding. At that point, the main concern of the organization’s management was the future of its members who had suffered because of the war. In addition, the management worried about the families of the war invalids and the war orphans whom the organization was committed to aid. In order to make sure that this welfare work would continue, even if the organization was abolished, the management set up Suomen Naisten Huoltosäätiö [the Foundation of Finnish Women] to which it donated a large part of the organization’s properties and funds (Lukkarinen 303). This foundation still exists to this day, though its name was changed in 2004 to Lotta Svärd Säätiö [the Lotta Svärd Foundation].

Under the terms of the interim peace treaty, the Civil Guards organization was abolished on November 7, 1944. Soon afterwards, on November 23 of the same year, the Lotta Svärd organization was also abolished. At the time of the abolition, the Lotta Svärd organization consisted of 232,000 members, of whom 150,000 were active members, 30,000 were supporting members and 52,000 were Little Lottas. Approximately 300 Lottas had been killed in the line of duty during the years the organization had operated.

The establishment of the peace treaty drastically changed the atmosphere in Finland. Thousands of organizations were abolished in accordance with the 21st article of the treaty, and the ideals the members had lived by were labeled as “criminal” by many politicians who wanted to avoid further conflict with the Soviet Union. Many former members of these abolished organizations had to either deny or keep quiet about their pasts for many decades. As a result of this, the Lotta Svärd organization was hardly even discussed for almost 50 years. Although the 1980s saw a national restoration which returned its honor to Lotta Svärd, the restoration could not fully erase the negative images that the peace treaty and its interpretations had left behind. This situation finally improved in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union, which changed the operating environment of Finland’s foreign policy, and thus also influenced the Finns’ interpretation of their own recent history.

In memory of those Lotta’s who served their country and who died for Finland

On September 13, 1991, a committee led by the Minister for Defense organized an event in celebration of the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Lotta Svärd organization. The purpose of this event was to give Lottas official recognition from the State for their work during the war years for the first time since 1944. The Finns’ attitude towards the Lotta Svärd organization had been getting steadily more respectful since the 1980s, but it was this event which encouraged former Lottas to start talking in public about their experiences as members of the organization. Since then, many associations which aim to uphold the memory and spiritual heritage of the Lotta Svärd organization have been set up all over Finland. Additionally, in recent years researchers have become more interested in the Lotta Svärd organization, and this has led to many research papers and memoirs being written. After almost 50 years of silence, the Lotta Svärd organization is finally gaining the attention it deserves.

While a large part of the above Post on the Lotta Svärd organization has history that has been “tweaked”, much it contains is historically accurate. The Lotta Svärd organization played an important role in supporting Finland’s national defense both materially and spiritually during the war years. Besides supporting the troops, the Lottas helped free soldiers for the front lines or other national defense duties by taking on tasks that would otherwise have belonged to men. One of the organization’s most important achievements during the war years was creating and upholding the nation’s will for national defense. The sheer number of members in the organization made it possible for the organization to influence both homes and the whole society by simply setting an example. Thus, it is greatly thanks to Lotta Svärd that Finland’s home front managed to mentally endure the war years so well. Although Finland had suffered greatly in the Winter War and the Continuation War, the results of the war could have been much more devastating for Finland without Lotta Svärd’s help. One can only speculate whether the Finland today would still exist as it is now if Lotta Svärd had never existed. They are an organisation whose members deserve to be remembered with respect and honour.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2015 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2015 Alternative Finland

3 Responses to Lotta Svärd Yhdistys