Origins of the Cadre-based Army in Finland

This is a rather lengthy look at the origins of the Cadre-based Army in Finland (as opposed to a Militia-based system) in the 1920’s, as well as covering Conscription, changes to the military’s Mobilization Plans and the increasing role that women played in the fully-mobilized Finnish Military in the inter-war years from 1920 to 1939. I’ll also briefly cover some of the changes in Military Training over the 1930’s, primarily around the introduction of the school-based Military Cadet organisation, membership of which became compulsory for both boy and girl-students in 1932. Military Training in the 1930’s will itself be covered.

The objective is to outline the foundations that were laid within the Finnish military in the 1920’s, and then to detail the high level training, mobilization and personnel-related changes that were made in the 1930’s and the impacts of these on military preparation and readiness. Also note that while there are constant references to the Suojeluskunta and Lotta Svärd organizations throughout , these organizations are not covered in detail – that comes next after I’ve finished working through the Cadre Army and Conscription.

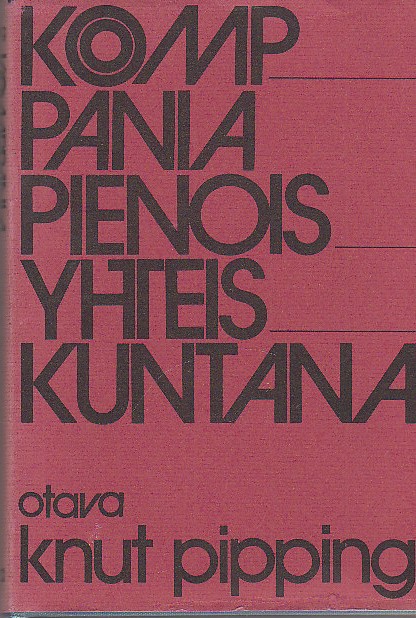

A Note on OTL vs ATL and sources: This chapter combines a great deal that is actual history together with ATL (Alternative Time Line) changes. Everything on Conscription in the 1920’s and the origins of the Cadre Army is OTL (Original Time Line), largely sourced from a PhD Thesis entitled “Soldiering and the Making of Finnish Manhood: Conscription and Masculinity in Interwar Finland, 1918–1939,” written by Anders Ahlback, which is the best English-language reference on the subject that I’ve come across. I’ve also referred back here and there to Knut Pipping’s “Infantry Company as a Society”, more for background information than anything else so you won’t see any plagiarism or direct references quoted from this book. Once you strip all the “Gender” and “Masculinity” references from Ahlback’s thesis, you actually have quite a useful historical record of Conscription in the Finnish Military in the inter-war period, as well as some good stuff on the origins of the Suomen Maavoimat (Finnish Army) as a Cadre Army, vs the Militia Army that was strongly supported as an alternative military structure at the time of Independence. Links to both of these documents are provided at the end of the article.

Changes to the Mobilization Plans are pure OTL, but when we get to the school-based Military Cadet organisation, the changing gender composition of the Finnish Military in the inter-war years and changes to Conscript Training and conditions in the 1930’s, this is all pure ATL, as are the references to the participation of Lotta Svärd members in semi-combat formations (and incidentally, the Finnish school dental nurse program referred to in a later post, although the information on the New Zealand school dental nurse program is accurate). OTL, Lotta Svärd members made an important contribution to the Finnish military during both the Winter War and the Continuation War, but this was always in non-combat roles, although I believe there were some city-defence AA-Gun units made up of Lotta Svärd members. Within this ATL, I have broadened, extended and formalized the participation of many more Lotta Svärd members within the Finnish military in a much wider combat support role and hopefully provided a justification for this that would be acceptable within the context of the period. If I haven’t, I’m wide open to suggestions / contributions on how it could be better justified.

Knut Pipping – Komppania pienoisyhteiskuntana (Infantry Company as a Society)

Anyhow, hope you enjoy reading it. I do recommend downloading the original Anders Ahlback thesis as well as Knut Pipping’s “Infantry Company as a Society” if you’re interested in reading more on the subject as, despite all the gender and masculinity references, the thesis is a great source of information on the origins of the Cadre Army and the debate around a Cadre Army vs a Militia Army that went on within Finland at the time, as well as covering the introduction of Conscription and the experiences of Conscripts at that time. And Knut Pipping’s “Infantry Company as a Society” is a one-of-a-kind study (its available from the Finnish Defence Forces website for download). For Finnish readers, there’s another good book by Juha Mälkki that I’m working through, “Herrat, Jätkät ja Sotataito: Kansalaissotilas-ja” – in English, that’s “Gentlemen, Lads and the Art of War: The Construction of the Citizen Soldier and Professional Soldier Armies into “The Miracle of the Winter War” during the 1920s and 1930s”. Only available in Finnish however. Seems pretty good, but seeing as I haven’t finished working my way through it, I’m leaving the content out although content from it may appear in later posts.

Also, if you want to read about the experiences of an actual conscript in training in the later 1930’s, I’d recommend three books – of which only one is written in English unfortunately for non-Finns. John Virtanen’s novel, “Molotov Cocktail” ( Virtanen served in the Finnish Army in the Winter War and was writing from experience. Unlike Linna’s “The Unknown Soldier” and the other two books mentioned below which were written for a Finnish audience, Virtanen wrote his book in English for the US market (he moved to the USA after WW2 and it’s an easier and lighter read) and it has a couple of good chapters near the start that cover Conscript Training really well. We see a lot of the issues in Virtanen’s novel that Pentti Haanpää (see below) raises, with men who have already left school and started working being called up and resenting this strongly, as well as those with a left-wing background resenting serving in the “White” Army. However, Virtanen’s novel is more middle-of-the-road than the two Finnish books covered below which are at either extreme of the views on conscription and military service – Virtanen is more in the centre and while his protagonist resents being called up, he actually comes to enjoy his service and becomes an NCO.

As I mentioned above, there’s also two further good books (in Finnish). Pentti Haanpää, in his book “Kenttä ja Kasarmi. Kertomuksia Tasavallan Armeijasta” (Helsinki, 1928), presented his readers with a bitter critique of the nationalistic rhetoric surrounding the conscript army. He depicted life in the army as a grey, barren and anguished world of physical hardship, meaningless drill, humiliating treatment and unfair punishment. The conscripts in his fictional short stories are men of little education; farm hands and lumberjacks used to hard work and plain living. Nevertheless, these men think of the barracks and training fields as “gruesome and abominable torture devices”. For them, the year spent in military service is simply time wasted. Haanpää described Finnish working men as brave soldiers in war but extremely recalcitrant conscripts in peacetime. Military service offended two basic elements of their self-esteem as men: personal autonomy and honest work. If they could not be in civilian “real” work, they saw more dignity in fighting the system by deceiving their officers and dodging service than in submitting to fooling around in the training fields playing what they saw as pointless war games. Very much the point of view of the left-wing working class.

By way of contrast, Mika Waltari (an author more widely known than Pentti Haanpää outside of Finland due to his best-selling novels) was two years older than Pentti Haanpää and had already attained a Bachelor of Arts Degree before doing his conscript service. His diary-like documentary of life as a conscript (Siellä Missä Miehiä Tehdään, Porvoo, 1931) is marked by an unreserved eagerness, depicting military training as almost like a Boy Scout camp with an atmosphere of sporty playfulness and merry comradeship. He is carried away by the “magical unity of the troop, its collective affinity”, depicting his army comrades as playful youngsters, always acting as a closely knit group, helping, supporting and encouraging each other. To Waltari, his fellow soldiers were like a family; the officers admirable father figures, and the barracks a warm and secure home. He pictured military service as the last safe haven of adolescence before an adult life of demands, responsibilities and duties. At the same time, the army was the place where boys, according to Waltari, learned of a higher cause and thereby matured into the responsibilities of adulthood. Much more of a middle-class conservative viewpoint.

Waltari, Haanpää and Virtanen certainly provide an interesting contrast in views and ones that well illustrate the divisions and debates at the time.

Also, you can download and read an english-language translation of Knit Pipping’s Infantry Company as a Society here if you’re interested (translation and PDF provided by Finland’s National Defence University).

And now……

The Finnish Army (Suomen Maavoimat): the Cadre vs Militia Debate

Following the Finnish Civil War, the Finnish Army was established as a “Cadre” Army. What this meant was that the permament Army personnel consisted of a small core of Officers and long-service NCO’s, while the bulk of the Army at any particular time was made up of Conscripts doing their period of military service.

In 1918, there had been no Finnish military for almost twenty years. Cultural and institutional military traditions in Finnish society had faded away, although they had not been completely forgotten. Finland had been spared from major military conflicts ever since the war of 1808-09, when Russia conquered Finland from Sweden. For most of the nineteenth century, there had only been a few Finnish military units, consisting of two or three thousand enlisted, professional soldiers. Universal male conscription was introduced in the Russian empire in the 1860’s–1870’s and the diet of the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland enacted a conscription bill of its own in 1878. For the elite of Finland, the eight conscripted rifle battalions and one cavalry regiment created around 1880, consisting of Finnish youngsters, led by Finnish officers and stationed in Finland, symbolised a significant step towards Finnish nationhood.

A “Finnish Army” was added to the old Swedish legislation, the provincial diet, and the Finnish central bank, currency and stamps introduced in the 1860’s. All these institutions marked Finland’s cultural and political autonomy from the Russian motherland. However, the Finnish state simply could not afford to feed, house and clothe whole age classes of Finnish men. Less than one young man in ten was therefore called up for three years of active military service in the 1880’s and 1890’s. Another 30% were placed in the reserve and given a mere 90 days of military training, spread out over three years. The majority of men were completely excused on an array of different exemption clauses, such as a weak constitution, bad health or being their family’s sole provider. Through the latter half of the 1800’s, Finnish political thinkers had been building a notion of Finland as a separate state in personal union with the Russian Empire, contrary to Russian views. Starting in 1899, the Russian central authorities took measures to counteract what they interpreted as an increasing threat of Finnish separatism and manifest the authority of nationwide legislation in Finland. Finnish nationalists perceived of this as perjury and an oppression of Finnish political autonomy and national culture. A matter at the core of Russian concerns was actually a reform of conscription in Finland. The Russian government wanted to homogenize it with military service in Russia and integrate the Finnish troops into the imperial army. The Finnish troops were therefore dismantled in 1901–1902.

The new military service law of 1901 resulted in nationalist mobilization and widespread “conscription strikes” in Finland. Fewer than half of those who received call-up papers were present at the draft in the spring of 1902, although the number of Finns who would actually have to perform military service under the new law was tiny; 500 of those eligible for the draft in 1902 and 190 in the next two years would be selected by lot. Eventually, the Russian authorities deemed it was better to have the Finns pay a hefty sum towards the defence of the empire than to have continued unrest in a strategic borderland and have Finnish soldiers as disloyal troublemakers in the ranks of the Russian army. The military service law was suspended in 1904 – and with it all conscription for the inhabitants of Finland. The Finns did not even have to send their sons off to the Great War of 1914–1918, where almost two million young conscripted men from most other parts of the vast Russian Empire perished.

The Russian Revolution, Finland’s declaration of independence in December 1917 and the Finnish Civil War of January–May 1918 brought military matters back to the fore in Finnish politics and society. A political struggle raged over what the duty to fight for your country would actually mean in the new Finnish national state. A majority soon accepted this as a duty, but a heated debate continued for years over exactly what this duty should entail in peacetime society. This is shown by an analysis of the parliamentary debates over conscription, which are used as a prism of the attitudes to the conscript army. Admittedly, what is said in parliament is usually a mixture of sincere opinions, expediency and political tactics. Many things that all agree upon are never voiced, whereas some minor detail upon which opinions differ can be object of much argument. These debates must therefore be read with care and caution. In a democracy, with an extensive freedom of speech such as Finland experienced in the interwar period, parliamentary debates possibly give an exaggerated impression of the resistance within society to government policies. Yet they also display how those in power try to publicly legitimate their course of action. Moreover, these debates were not “just rhetoric”, but had a direct impact on the institutional arrangements of conscription and military training.

Two different models for the military were competing with each other in the political arena: the militiaman and the cadre army soldier. In the militia system, there would be universal conscription but no standing peacetime army. All those liable for military service would gather at regular intervals for a few days or weeks of military training, and only a small number of officers would be full-time military professionals. In the cadre army system, as used in the German, Russian and Austrian empires before the world war, the conscripts lived fulltime in a standing conscripted army for a fixed period of time – usually one to two years – and were given intensive military training by a relatively large corps of professional officers and NCO’s. In case of war and mobilisation, this standing army would form the “cadre” and the organisational framework, with the Army itself would be filled out with reservists. (Note that after the mobilisation system was reformed in 1932, Finland did not technically speaking have a cadre army any more. In this post, the term “cadre army” will be used when discussing the debates in the 1920’s, instead of the perhaps more descriptive “standing army”, since it was the term used by contemporaries. For the contemporary understanding of the militia system vs the cadre army system, see the parliamentary committee report on conscription in 1920, Asevelvollisuuslakikomitean Mietintö, Komiteamietintö N 23, 1920, pp. 48–50, 77).

The day after Finland had declared independence on December 6th, 1917, the Finnish parliament started debating a bill that proposed the establishment of the national armed forces. Fundamental questions were raised for debate, from the basic ethical justification of armed forces to their intended purpose, whose interests they would serve, whom they would actually be directed against, as well as what kind of educational and moral impact army life would have on young men. In the prolonged and heated debate, which both proponents and opponents understood as concerning a crucial political decision, a vast array of different arguments were put forward, displaying the scope of conflicts and disagreements over military, security and foreign policy.

After the February 1917 revolution in Russia, Finnish society had entered a state of disorder and uncertainty (as we have seen). The political system of the Grand Duchy regained its autonomy, which had been circumscribed by the Russian war administration, but large Russian military detachments remained stationed in Finland. Russian officers had been murdered by their men at the beginning of the revolution and the remaining officers had difficulties controlling their men. There were instances of Russian soldiers committing crimes, causing disorder and terrorising Finnish civilians. More importantly, there were strikes and demonstrations as the workers’ movement tried to seize the opportunities offered by the general upheaval. Food shortages caused by the international situation provoked riots and strikes by farm workers in July and August resulted in outbursts of political violence. The gendarmerie had been closed down by the change of regime and the maintenance of order in towns taken over by local committees and militias.

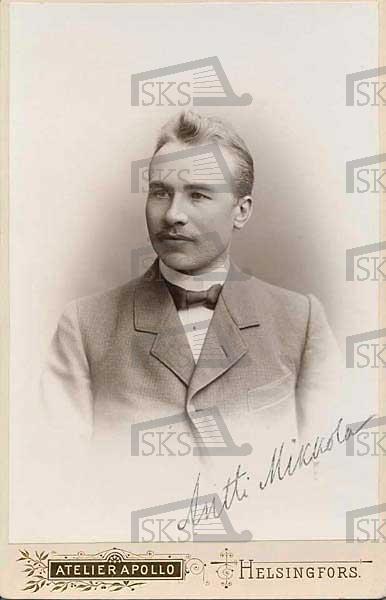

Starting in the spring of 1917, citizens’ guards were springing up to fill the void left by the paralysed state authorities. At first these were mainly “Red Guards” formed by socialists and workers, but as a reaction, ever more non-socialist civil guards, also known as “White Guards” or “Suojeluskuntas”, followed suit. In July, the provisional Russian government dissolved the Finnish provincial parliament, which had a social democratic majority. The new parliament, elected in October, now had a non-socialist majority, which made the carrying out of legal reforms to appease the worker’s unrest more difficult. The Social Democrats still obtained 45% of the popular vote, only 2% less than in 1916. Following the October Revolution in Russia, the Social Democrats arranged a general strike in Finland, which in places disintegrated into violent crime and clashes between Red Guards and Suojeluskuntas. Over 30 people were killed. Hopes of a socialist revolution in Finland and fears of a civil war were very much in evidence, as political polarization deepened.In this situation, the liberal representative Antti Mikkola (1869–1918) submitted a motion to parliament, supported by MPs from all non-socialist parties, demanding that a national military be created and that the Russian troops leave the country immediately.

Antti Mikola (1869-1918)

The stated purpose of Mikkola’s motion was to avoid a civil war by providing the lawful government with organised regular armed forces. Mikkola described this new army as a “people’s army”, temporarily based on the old conscription law of 1878, until a “people’s militia based on universal conscription” could be developed along the lines of the Swiss militia system. This was an obvious attempt to win the support of the Agrarian Party and the Social Democrats. These popular parties of the political centre and left both harboured a deep mistrust of the “cadre” armies of the Russian and Prussian type, which they associated with monarchism and with the aristocratic authoritarianism of nineteenth century society. This should not be understood as a resistance to the idea of the citizen-soldier as such, or against the duty to take up arms to defend one’s country. Rather, it expressed an aspiration towards a more democratic, republican, even anti-authoritarian vision of a military system where the citizen-soldier could retain more of his autonomy as a free citizen.

The Agrarians and Social Democrats between them actually had a majority in parliament for most of the period 1917–1922, but they were unable to unite around this issue. Due to the inflamed domestic situation in 1917, the debate on Mikkola’s motion became a power-struggle between socialists and non-socialists over whether parliament should grant the government any kind of armed forces to restore order. The Social Democrats believed that the proposed army would primarily be used against the Red Guards and filibustered the bill. The first reading dragged out into January 1918, as more than a hundred addresses were made. Parallel to the endless debate, the Social Democrats actively campaigned against the bill among their voters. Their critique of a national conscript army in parliament thus became wide spread. It can be assumed that the arguments they used were well remembered during and after the Civil War of 1918, when a military system bearing a strong semblance to the kind they had criticized was indeed established.

The main thrust of the social democratic representatives’ critique of the proposal was the assertion that the planned armed forces were not really intended to protect the country from external threats, since any military defence that Finland could establish was negligible in comparison to the resources of the surrounding great powers. Its real purpose, they claimed, was to defend an economic system of capitalist exploitation against the just demands of the working class. They referred to examples from Russia, Germany, France, England and America, where capitalists had allegedly used the military to crush the workers’ legitimate struggle for better conditions. They also dismissed the Swiss militia model, which they claimed had proven fit to be a tool for the class interest of the Swiss bourgeoisie and condemned by the Swiss workers. If the bourgeoisie tried to enforce conscription according to the old law of 1878, the workers would not obey. “The conscious youth of Finland will not sacrifice its time, health, life and limb for the spoils of the bourgeoisie and to support its oligarchy”, stated MP Yrjö Sirola.

In addition to their tactical reasons for opposing the bill, the Social Democrats were drawing on a long tradition. In the second half of the nineteenth century, German social democrats co-opted liberal ideas from half a century earlier, about standing armies as instruments of absolutist power and a hindrance for liberal democracy. Drawing on republican notions of free men and citizen defending their liberty and their people, liberals in many European countries had envisioned some form of civic militias, “arming the people” as an alternative way of protecting both the national borders and civic freedoms. From the 1860’s onwards, the emerging social democratic movement continued both the critique of standing armies and the enthusiasm for the militia system of democratic liberalism. The German social democrats regarded the Prussian cadre army as a political and moral threat to the working classes. They claimed that it served only the interests of the ruling classes, both domestically and abroad, and pointed out that its leading positions were reserved for members of the social elites although its costs were born by the working classes. Social democrats thought that military training in the conscript army stifled young working class men’s potential for intellectual development. They regarded military education in its existing form as an education in coarseness, brutality, stupidity and slavishness. Unable to essentially change the military system, the German social democrats carried on a continuous criticism of the cadre army in parliament, for example exposing case upon case of scandalous maltreatment of conscripted soldiers.

Repudations of capitalist “militarism” and “imperialism”, especially the standing armies of the colonial powers, became an important part of international socialist ideology after the founding of the Second International in Paris 1889.15 The influential German social democratic Erfurt Programme of 1891 included demands for replacing the standing cadre army in Germany with a Volkswehr, a militia army. It also called for international conflicts being settled peacefully in arbitration courts. The analogous Forssa Programme, adopted by the Finnish Social Democrats in 1903, demanded decreased military burdens, a militia to replace the standing army, and “the idea of peace realised in practice”. An important pamphlet in this tradition was Karl Liebknecht’s Militarismus und Anti-Militarismus (1907), which was promptly translated and published in Swedish in 1908 and in Finnish in 1910. Many of the arguments used by the Finnish Social Democrats in 1917 can be found in this work.

The debate on the Army expanded to include the moral consequences of military education. The Social Democrats claimed that Mikkola’s motion would revive the old Finnish conscript army, “that compromise between Russian and Finnish militarism of the 1870’s, a perfect copy of Russian militarism”, with an aristocratic officer corps that formed a “closed and insular caste”. The Finnish people, they said, had always detested that institution, and young men had done all they could to evade being drafted. It was socially unfair, since the sons of the wealthy could use various exemption rules to dodge conscription. Worst of all, it was a place where young men of the working classes were brutalized by the officers’ teachings and the immorality of life among soldiers. Anni Huotari and Hilja Pärssinen, the two female socialist MPs who participated in the debate, both opposed any kind of militarisation.

Anni Huotari, Socialist MP

Huotari stated that Finland’s women regardless of political colour “needed their husbands, brothers and sons to take care of and protect their homes”. They would not allow their men to be “packed into the morally corrupting atmosphere of military barracks.” MP Antti Mäkelin recollected serving in the old conscript army himself in 1894, at a time when food riots had occurred in Helsinki, shops been plundered, and the military was put in a state of alert. According to Mäkelin, the officers lecturing the soldiers drummed into them that they must fire on command, no matter what – even if their own parents or siblings were in the targeted mob. “Is that not a horrible education?” exclaimed Mäkelin: “There a father who has done everything to make his boy a man, there a mother, who has suffered good and bad times with her child, trying to make him a decent man. And when he has become a decent man, a brisk youth, a strong man, he has to kill his own mother and father, if the interests of capitalism demand it and the capitalist orders him to. This is what it is like, my good friends, the spiritual education you get there!”

Vilkku (Vilhelm) Joukahainen, Agrarian Party

Non-socialist MPs countered this description of the old conscript army with recollections of their own, pointing out how the physical, civic and military education received there had all been excellent, as proven by the fact that former soldiers could be seen in many responsible occupations in society, often enjoying great esteem in their local communities. “Thus our conscription law did not produce depravity, but on the contrary, it lifted many a depraved youth to a new life”, said Vilhelm Joukahainen of the Agrarian Party. Others stated that it did not matter what the old army had been like, since now the Finns for the first time had an opportunity to create a truly national military. Agrarian MP Juho Kokko envisioned that the new national form of conscription would infringe as little as possible on individual freedoms, “there will be quite another relationship between the men and the teachers, it will be as democratic as only possible”. Thus, he indirectly subscribed to the criticism of the old cadre army, although he claimed that many who had served there were now highly respected men in their local societies. He thought many of the trouble-makers “robbing and arsoning” in the recent riots could be educated into proper, orderly, real men through military training.

Paavo Virkkunen

Most articulate in his visions of the positive moral qualities of the army-to-be was the Rev. Paavo Virkkunen (1874–1959) of the conservative Finnish Party, future Speaker of Parliament and Minister of Education. According to Virkkunen, Finland needed armed forces to preserve and represent its authority as a civilised state, to enforce domestic order, and “for the advancement of national backbone and conduct in our life as a people.” Most representatives of the non-socialist parties confined themselves to presenting a national armed force as a natural and inevitable institution in an independent and sovereign state.

Socialist and Non-Socialist Anti-Militarism

International socialist anti-militarism had differing threads. Some socialist opposed “bourgeois” armies, but accepted the violence of socialist revolutionaries, while others were genuine pacifists. This was demonstrated by the ambiguity of the Finnish Social Democratic MPs in 1917. Some Social Democratic MPs made it understood that they were ready to support a national militia-based army, but only “when true democracy with real civic liberties has been realised here and reforms carried out which are worthwhile to defend by armed struggle.” MPs Yrjö Sirola and K.H. Wiik explicitly underlined that they were not “tolstoyans”, i.e. pacifists but believed in the right of citizens to arm themselves in order to defend their lives and civic rights. Others declared that ordinary people increasingly opposed any form of armed forces and that Finland had no need of an army. The country could not afford the requisition and maintenance of “modern murder tools” nor keeping “thousands of men languishing in barracks instead of doing something useful”. The Christian commandment to love one’s neighbour was also cited. There were calls for Finland to be “a pioneer in the cause of peace” and expressions of amazement and disgust over how the bourgeoisie wanted to enforce the “capitalist curse” of militarism in Finland at the very moment when “the exhausted peoples of Europe are crying out against the raging war-madness”.

The resistance against a militarisation of Finnish society was not limited to the socialist movement. During the fall of 1917, some “bourgeois” groups, especially women’s organisations, had issued pacifist manifestos objecting to the establishment of Finnish armed forces. Ever since the mid-nineteenth century, there had been notable pacifists among Finnish clergymen, scientists and politicians. Pacifism had been an available and respectable position in Finnish society for a long time, especially among the idealistic proponents of popular enlightenment. Historian Vesa Vares has even characterised the Zeitgeist in Finland in 1917 as “very pacifistic” and the mood among moderate conservatives on the eve of the Civil War as anything but belligerent. He points out that the only heavyweight politician to publicly take a stand for the proposed armed forces in the contemporary press was K.N. Rantakari of the conservative Finnish Party.

Gustaf Arokallio

Sabre-rattling was definitely not the order of the day among the non-socialist mainstream.Yet in the parliamentary debate only two non-socialist MPs, Gustaf Arokallio of the Young Finnish party and Antti Rentola of the Agrarian Party – both clergymen – resisted the proposed new Finnish Army. They argued that conscription sustained a warlike spirit even in small nations and dragged down young men, especially those from the bottom layers of society. They agreed with the socialists that the old conscription system of 1878 was repugnant to the majority of the people. Therefore, the re-enforcement of conscription would only accelerate the country’s slide towards civil war. The proposed army would do more harm than good, they thought, since Finland’s independence could neither be achieved nor preserved by armed forces, but only by national unity and international acknowledgement of Finland’s neutrality. These pacifist voices were hailed with cries of approval from the left, but found no support among their party colleagues. In view of the escalating political violence in the country, all the other non-socialist speakers stressed that a military institution was needed to maintain law and order and to protect all citizens’ property and personal security.

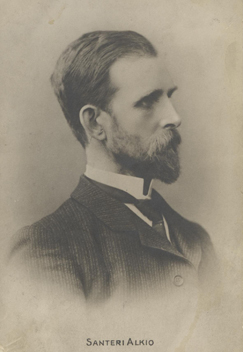

Some of the proponents of the bill gave assurances that they completely supported international disarmament and peace efforts, but said that as a small nation, Finland could not be a forerunner or take another route than that taken by the surrounding nations. As long as other countries were heavily armed, Finland had to gather all its strength to secure its independence. It was, in summary, every Finnish citizen’s regrettable, but inescapable duty to submit to these realities. Several non-socialist MPs dismissed the social democratic anti-militarist rhetoric as a grotesque farce, pointing out that as they spoke, the Red Guards were acting in an increasingly threatening fashion and taking on an ever closer resemblance to a full-scale army organisation. MP Santeri Alkio (1862–1930), the central ideologue of the Agrarian Party and a onetime peace idealist, stated that he did not believe that the proposed armed forces would be able to fend off an external enemy. However, as the Red Guards had become a threat to the democratic system and to Finland’s independence, he said he had been forced to abandon his earlier idealistic notion that Finland could do without “a bloody sword to secure the government’s authority”.

In midst of all the controversy, some things were taken for granted by both socialist and non-socialist speakers in this debate. The non-socialists envisioned military service as a place where unruly uneducated men of the lower classes could be given basic education and be educated and trained into decent honourable citizens – turning hooligans into pillars of society. A common feeling of patriotism would be induced in men from different classes and divert their attention from inner divisions towards common challenges. Thus, the army would support the prevailing social order, both by the physical enforcement of law and order and by an ideological influence. This was roughly what the socialists thought too – only to them this represented the dystopian preservation of an unjust society and the disciplining of the exploited workers by their induction with a false consciousness. In their view, the proposed army would produce ideologically blinded lackeys of capitalism, “hired murderers”, corrupted beings with no moral principles who would shoot at their own parents on command; men whose manpower was wasted for no useful purpose as they lazed away in the garrison, prevented from doing honest work and debauched by the vices of barracks life.

Opposed to this counter-image of the military and of democratic citizenship, a very different socialist citizen-soldier was implicitly outlined. This erect and courageous class-conscious worker would thwart capitalist militarism by refusing conscription and would take up arms only at his own will. He would never merely obey orders from above, but only fight for the just causes of emancipating the working class or warding off an external aggressor. All parties thought that the proposed army was primarily intended for the restoration of domestic order, although they differed in their views of what this order should be. There was a prevailing notion across the partylines, although by no means unanimous, that a Finnish national army would not stand any chance against the armed forces of any of the surrounding greater powers. These sceptical notions of the meaningfulness of armed struggle against foreign foes would soon take a sharp turn, whereas the various notions of the moral impact of military training would prove very tenacious throughout the interwar era. A decision on Antti Mikkola’s bill, however, was never reached, as the outbreak of civil war in January 1918 interrupted the work of parliament. Mikkola himself was imprisoned and shot by Red Guards in Helsinki on 1st February 1918, three weeks after the end of the debate.

The Civil War and the creation of the “White Army”

The Finnish national armed forces of the interwar “first republic” grew out of the military mobilisation against the attempted socialist Revolution and the resultant Civil War of January-May 1918. The winning non-socialist side referred to this armed conflict as “the Liberation War”, since they understood forcing the Russian troops out of the country and securing Finland’s political independence as the central objectives of their own troops. Yet the Bolshevik government had officially recognised Finland’s sovereignty in December 1917 and the Russian troops in Finland did not appreciably interfere in the fighting. The socialist leadership had declared no wish to rejoin Finland with Russia. The term “liberation war” thus carried a politically charged claim that the essential meaning of the war had not been an internal struggle among Finns over the future political and economic system, but a national struggle for Finnish independence from Russia. It was a way of insisting that the war had not been a tragic war between kith and kin, but indeed the valiant war of liberation planned and prepared for by Finnish nationalist activists long before 1918.38 “The Liberation War” also signalled that Finnish independence was the result of the deeds of Finnish freedom fighters, not the haphazard outcome of the internal collapse of the Russian Empire.

According to this nationalist viewpoint, the military struggle of the White Army was key to Finland’s national rebirth into an independent state. Thus, the founding of the national state became intimately connected to the military and to national valour, just as it had been in other noteworthy model cases of national liberation such as the United States, revolutionary France, and Prussia at the time of the Napoleonic wars or the Franco-German war of 1870–1871. The “whites” afterwards liked to describe this “Liberation war” in terms of a spontaneous rising of the freedom-loving, patriotic and lawabiding Finnish peasantry. Finland, still being a predominantly agrarian country, where rural life was often idealised by conservative nationalists – themselves often belonging to groups of the urban elite – the free-holding male peasant was crafted into the archetype of the valorous Finnish citizensoldier.

One version of this story was offered to Finnish and foreign visitors at the first Finnish Fair held in Helsinki in 1920 through a special multilingual issue of the army magazine Suomen Sotilas: “The Finnish Army was created in an hour of peril, when the hearts of the people were kindled by patriotism. – It rose into existence from the imperative necessity of homes and hearths having to be defended against the onslaught of native and foreign rebels, whose villainy had brought the old culture of the nation to the verge of destruction through rebellion. Then the peasants of Finland rose voluntarily to fight for their lawful Government. They left their homes hidden in the snow-wreaths of winter and gathered round their great Commander to expel the enemy from the borders of the land, fighting hard battles nearly unarmed and enduring want and hardship. And finally they carried off the victory. This glorious host of volunteers in the Battle for freedom formed the basis of the present standing army of Finland.” The “glorious host of volunteers” here refers to the Suojeluskuntas, the Civil Guards, who (as we have seen earlier) formed the initial fighting units on the non-socialist side as the political tensions exploded into open civil war at the end of January 1918..

Motivations for soldiering in the 1918 Finnish Civil War

After the war, both socialists and non-socialists mostly depicted the men on their own side as going to war out of patriotism or class-consciousness, idealism and valorousness, whereas the opponents were driven by economic self-interest, bloodthirstiness or sheer villainy. In reality, most Finnish men who fought the Civil War probably joined because they were forced to – for economic, social or legal reasons. There was no general belligerence or enthusiasm for war in Finland 1918. The “patriotic” citizens on the ‘white’ side who volunteered to fight against the socialists in 1918 scarcely constituted sufficient numbers to actually win the war. The Civil Guards were a volunteer corps based in local communities. They sent some detachments to the front, but as it transpired, the majority of the guardsmen were reluctant to leave their home districts. They thought it was their duty only to defend their own village or municipality. This soon provoked demands for the introduction of universal conscription by activists trying to mobilise the “white” population. In mid-February, an editorial in the Ilkka newspaper, mouthpiece of the Agrarian Party, complained that some regions in the government-controlled territory were filled with “cowards and layabouts”. Ilkka demanded that the old conscription laws should be enforced. “He who has no manliness and sense of honour must be forced – forced to protect his home, his family, his kin and his property”, Ilkka wrote. In some districts, citizen’s meetings had already voted for introducing municipal conscription. This, however, should not be understood as evidence of a general atmosphere of war enthusiasm, but rather as indications of a perceived lack of a proper readiness to fight voluntarily.

The “White” Guards who actually fought at the front included members from all layers of agrarian society, including workers, although half of them were from freeholder families. The voluntary guardsmen at the front were highly motivated, but had received little or no military training before the war. Their notions of discipline were often different from those of the White Army command, which mainly consisted of Finnish military professionals who had made a career in the Russian army. These professional officers were often Swedish-speaking members of the old social and economic elite. The rank-and-file guardsmen had strong notions of their autonomy as voluntary troops, and often took a suspicious attitude towards professional officers and authoritarian leadership. There were incidents where civil guards would disregard orders from the headquarters or refused to accept commanding officers they disliked. Stories were later told of whole units that simply decided to leave the front for the weekend to go home to their village and go to the sauna, whereupon they would return to the front, clean and rested.

The Red Guards were in principle also voluntary troops. At the outset, there was even a formal demand that red guardsmen must be members of some organisation within the workers’ movement. According to historian Jussi T. Lappalainen, those who joined the red guards before the Civil War or in its early stages did so for idealistic reasons. The strong solidarity within the workers’ movement made even previously anti-militarist groups join the fight once the war broke out, for example the social democratic Youth League in Helsinki. However, due to continued food shortages and the shutting-down of many civilian working sites, many red guardsmen probably joined the guards mainly to support themselves and their families. There was most likely also a strong group pressure within many workers’ organisations. Just as on the white side, the local red guards were often reluctant to leave their home district and go to the front. However, conscription was never introduced in the areas controlled by the socialist revolutionaries. Not counting several instances of compulsory enlistment at the local level, the leadership of the insurgency adhered to the principle of revolutionary volunteers, even in the face of pressure from their own district commanders and impending military catastrophe.

There were obvious similarities between the anti-authoritarian notions of military discipline among the Civil Guards and the Red Guards, but the phenomenon was more extreme among the socialists. Many detachments elected and dismissed their own commanding officers. There were attempts at transferring the democratic meeting procedures from workers’ associations to military decision-making. According to Lappalainen, by March 1918 the spread of absenteeism, desertion and refusal to obey orders was making purposeful leadership almost impossible. Harsh punishments seem to have been incompatible with Finnish socialist ideology – capital punishment had expressly been abolished at the beginning of the revolution in Finland. The government troops at the front were in dire need of reinforcements for an offensive to end the war. In a declaration on February 18th 1918, the senate called all male citizens liable for military service to arms, supporting the call-up on the legal authority of the conscription law of 1878 that was now declared never to have been formally abrogated. Historian Ohto Manninen has assessed that the population in the territories controlled by the government generally accepted this decision, with only scattered and isolated expressions of opposition. The preamble to the 1878 law stated that every male Finnish citizen was liable for military service “for the defence of the throne and the fatherland”.

Some who refused the call-up disputed the applicability of this law in an internal conflict. As objectors pointed out, there was no throne any more. Some propertyless workers scornfully stated they had no fatherland either since they had no land. Some questioned the legal authority of the senate to decide on such a matter. However, according to Manninen’s calculations, a mere 3–10% of those liable dodged the call-up. The motive for avoidance varied, from socialist sympathies to a desire to remain neutral or because of a conscientious objection. An important further motive was naturally fear – not only fear for one’s own life, but often for the livelihood of those one provided for. The introduction of universal conscription changed the nature of the White Army, and moved it away from a voluntary citizen’s movement towards a compulsory state institution. As the White Army’s numbers peaked towards the end of April 1918, conscripted soldiers made up about 55% of the White Army or about 39 000 troops. The remaining 45% consisted of volunteers in the civil guards and enlisted troops, and some of these had probably volunteered or enlisted already knowing that they would otherwise be conscripted. In general, Ohto Manninen characterises the conscripted troops as better disciplined and organised than the voluntary guards. Yet they occasionally posed problems of another kind for their commanding officers, providing some forewarning of the problems that the post-war conscript army would face: recalcitrance, shirking and malingering due either to leftist leanings among the soldiers or general indifference to the government’s war aims.

A “National” Army in a Divided Nation

While the Civil War ended in May 1918, the government’s “white” army was never dismantled. When the fighting ceased, army detachments were used to secure the country’s borders and guard the internment camps for the red guards, where over 80 000 people were detained awaiting trial. The voluntary civil guards soon returned home. Most of the conscripted troops were also demobilised, but the youngest conscripts were kept on duty and the army stayed in a state of alert. There were thousands of deserters, red guardsmen and other “politically untrustworthy citizens” still in hiding. Until and beyond the signing of a peace treaty with Soviet Russia in October 1920, the immediate threat of a war with Russia only gradually diminished. In the wake of a German military invention in the Civil War, requested by the Senate in Vaasa (and over the strong opposition of Mannerheim, it must be said), there were also 15 000 German soldiers in the country. By resorting to German arms deliveries and military support in the Civil War, the Finnish government had made Finland a close ally, if not a vassal state of the German empire.

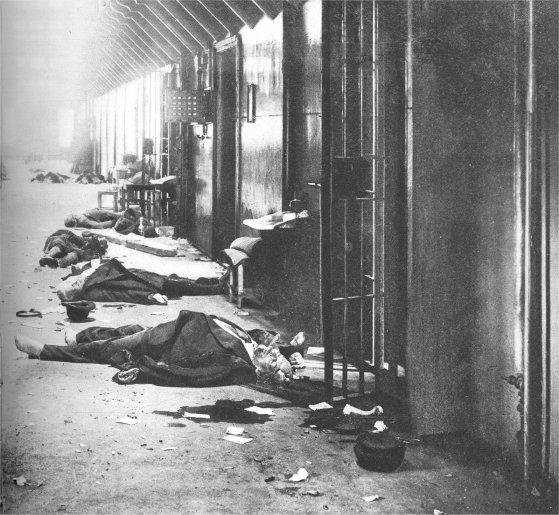

During the summer and fall of 1918, as the Great War on the European continent still raged on, German military advisors supervised the reorganisation of the national armed forces and the military training of conscripts in Finland, naturally with a keen eye for German military interests. However, they had to leave abruptly in December 1918 following Germany’s military collapse on the Western Front. Immediately after the Civil War, there were highly conflicting attitudes towards the national armed forces among the population. The socialists associated both the Civil Guards and the conscripted Army with their military defeat and the maltreatment and summary executions of red prisoners in the prison camps. It has been calculated that some 5,200 Reds were killed in action, but another 7,200 were executed, shot or murdered in the so-called “white terror” towards the end of the war. An even greater number, 11,600 men, women and children on the losing side died from starvation or disease in the prison camps. The executions and atrocities in the internment camps surrounded the defeated with a horror that soon turned into deep bitterness, as the winners meticulously investigated any crimes committed by the insurgents, but protected the white terror with a pact of silence and oblivion. These experiences and stories also fed the hatred of the ‘white’ army, which in the losers’ eyes fitted only too well into the descriptions articulated by social democratic politicians before the war; a murder tool in the hands of capitalists to break the backbone of the working class.

Viipuri Prison 1918: A farewell from the Red Guard. Red Guard prison guards executed their prisoners in this prison before leaving town

However, the bitterness and suspicion was certainly mutual and well-founded on events. More than 1,400 non-socialist “class enemies” had been executed or murdered by the red guards during the revolution, and 3,400 Whites killed in action by the red guards. Finnish conservatives were deeply shocked, hurt and traumatised by the attempted revolution and the rancorousness of the proletarians, so far removed from nineteenth and early twentieth century images of a humble and hard-working Finnish people, struggling peacefully towards cultural and moral advancement under the leadership of the educated classes. Those non-socialists who had expressed pacifist leanings before the war were in many cases “converted” by the shock of the Civil War to ardent support of the new armed forces. Vesa Vares illustrates this with many examples, e.g. that of the Agrarian MP, Rev. Antti Rentola who had resisted the creation of armed forces in December 1917. In February 1918, he wrote of the civil war in the Ilkka newspaper as a “holy war” since it was “no militarist war”, but “the use of the sword of authority belonging to the divine order to punish the evil. (…) This is God’s war against the Devil.” There had been a shift in mentalities. Most of the non-socialists thought of the “white” army as a heroic host of liberators who had given the red “hooligans” what they deserved, restored law and order, and secured Finland’s independence from Russia. History seemed to have vindicated the activists who had tried to mobilise the nation into military action.

As the initial excitement over victory ebbed, an unfavourable attitude towards the army spread beyond the working classes over the fall of 1918. This had to do with reports of food scarcity, epidemics, deficient lodgings and ill-treatment of conscripts. In the wake of the war, there was a general food shortage over the whole country and the brand new army was underfed, underfunded, understaffed and poorly quartered in old Russian barracks that often were in a state of major disrepair. The officer corps was mixed and ridden with internal tensions, as former Russian imperial officers who had loyally fought in the tsar’s army until 1917 and the so-called Jäger officers, militant nationalist activists who had been trained in the German army during the Great War, did not always get on well together. There was widespread dodging of the call-ups in 1918, desertions and incidents of mutiny in some detachments that the military authorities blamed mainly on the men’s undernourishment. The material circumstances slowly ameliorated and dodging and desertions soon decreased. Yet the build-up of the regular army was for many long years obstructed by heavy ballast from the Civil War.

The militiaman challenging the cadre army soldier

The conscript “cadre” army that had emerged from the confusion of the Civil War was regularised through conscription laws passed in 1919 and 1922. Yet it did not go unchallenged. First the Agrarians and then the Social Democrats presented their own visions of national defence and Finnish soldierhood, based on different configurations of democratic, republican and socialist idealism, and highly critical of the system at hand. As the Finnish parliament resumed its work in the summer of 1918, its members had been reduced almost by half. All but one of the Social Democratic MPs were absent. Some were dead; others had fled to the Soviet Union or were imprisoned facing charges for participation in the red rebellion. As the government in November 1918 presented this rump parliament with a bill for adjusting the old conscription law to the new circumstances, the political frontlines were therefore quite different than in 1917.

On the threshold of the civil war, the agrarian agenda for a people’s militia had drowned in the escalating ideological quarrel. In the new circumstances after the war, however, the Agrarians suddenly found themselves in opposition to the other non-socialist parties. Their alternative to a “conventional” conscript-based Cadre Army was highlighted for a short while, as they demanded that the cadre army born out of the Civil War be replaced by a people’s militia as soon as possible. Historian Juhani Mylly has located the origins of the people’s militia idea within the Agrarian Party to its main ideologue Santeri Alkio’s political thinking at the time of the party’s founding in 1906: “In the style of an idealistic leader of a youth association, Alkio at that time argued for the superiority of the militia system in relation to the cadre system, by referring, among other things, to those moral dangers he thought the youngsters would be exposed to far from their homes”. Mylly also points out that the Finnish Agrarians shared their distrust of standing armies and their interest in the alternative people’s militia model with agrarian parties in many countries, especially in Eastern Europe. The people’s militia model was well suited to the democratic and republican ideology of the Finnish Agrarian Party, where it was seen as a kind of people’s army that brought the issue of national defence concretely into the everyday life of ordinary citizens. To this peasant’s party, always economical with the taxpayer’s money, the relative inexpensiveness of the militia system was also of great importance.

Republican and Authoritarian Military Traditions

The Finnish Agrarians admired and supported the Suojeluskuntas (Civil Guards). In 1918–1919, they regarded them as a model and inspiration for how the national defence system should be organised. They resisted the separation of the Suojeluskuntas from the Army in 1918 and wanted to integrate them into the national armed forces. In accordance with European liberal democratic traditions, they associated a standing Cadre Army with the upper class life-style of aristocratic officers, pointless drilling, ostentatious display and parading, as well as moral corruption of the conscripts, especially through drinking. According to Mylly, the Agrarians thought the Cadre Army was an anti-democratic tool for the unsound ambitions of warlike monarchs. This notion must have been strengthened by the fact that the conservative government proposing a conscription bill in November 1918, based on the Cadre Army system, had for months been busy trying to make Finland a monarchy closely aligned to the German empire. The sovereign was even mentioned in the wording of the bill, although the parliament of 1917 had declared Finland an independent republic.

Having recently experienced the rebelliousness and “political immaturity” of the working classes, the right-wing parties were anxious to shape a new form of government that would ensure political stability and guarantee the educated elites a certain measure of control. The plans for a monarchy were wrecked in November-December 1918 by the German defeat in the Great War. Due to pressure from the victorious Western powers and the other Scandinavian countries a centrist republicanism gained the upper hand, including a policy of conciliation towards the workers’ movement: broad amnesties for “red” prisoners and permission for reformist Social Democrats to re-enter parliamentary politics. Nevertheless, the solid establishment of the Cadre Army system can be seen as one part of the larger political project of securing the social status quo.

The origins of the Prussian cadre army system, which in its 1918 German Reich version served as a model for the build-up of the Finnish Army, can actually be found in a very similar need to control the explosive force of arming the lower classes. Military historian Stig Förster has described the development of conscription in nineteenth century Prussia, and eventually in the German Kaiserreich, as the integration of the new, explosive forces of “a people in arms” into the traditional standing army organisation with its strict discipline and hierarchical command structure. Early nineteenth-century professional officers and military experts regarded the various forms of self-mobilised people’s militias that sprang up in the era of the democratic revolutions as inefficient in the long run and, above all, very difficult to control. In order to ensure the Prussian monarchy’s absolute control of the conscript army, even as an instrument of power in domestic affairs, conscripts drafted for active service in peacetime were subjected to an intense military training lasting three years, during which the conscripts lived in garrisons relatively isolated from civilian society. In the same way, the cadre army system in Finland should ensure that the conscripts were disciplined into a military force controllable by the government. Although the militia model resembled the organisational principles of the cherished Suojeluskuntas, the resemblance to the Red Guards may well have been too close for bourgeois sensibilities.

The Agrarians’ case for a People’s Militia

Since the Agrarians could not find support for their Militia model in the 1918 rump parliament they first tried to get the whole conscription bill rejected, and then concentrated on arguing that two years of military service for 20 year-old’s as the government was proposing was far too much. Agrarian MP’s Santeri Alkio and Antti Juutilainen both depicted the Cadre Army system as a relict of yesterday’s world and the military experts propagating it as “adepts of the old Russian school who cannot grasp that armies in today’s world can be trained and put together more rapidly than before”. Alkio argued that interrupting young men’s working lives and plans for several years would only provoke discontent and thus weaken the army. He held up the people’s militia model as the future goal to strive for. “Finland’s experience during [1918] shows that on this basis, as the people rises to defend its fatherland and its freedom and to create new conditions, a shorter training will suffice. All that is needed is patriotic enthusiasm”.

Mikko Luopajärvi (1871-1920)

In another flush of nationalist self-congratulation, Agrarian MP Mikko Luopajärvi (who was also the editor of Ilkka magazine) claimed that due to the Finns’ fighting spirit, the arrival of small and rapidly trained Finnish voluntary troops on the battle scene had been a turning point in the Estonian war of independence. Asserting that the Finns accomplished more with merely a brief military training than the Estonians, who had served for four or five years in the Tsar’s army, Luopajärvi tried to prove that it was more important to ascertain that Finnish soldiers had the right motivation to fight than to give them a very thorough military education.

His party fellow Juho Niukkanen agreed and quoted German military experts who had praised the Finnish soldier material as better than in many other countries. Not only was an overly heavy military service thus unnecessary, Niukkanen claimed, it was irreconcilable with the Finnish national character itself. It has also been said of the Finns, that “whereas they are good soldiers, they are also stubborn and persistent. They cannot wantonly be hassled or commanded against their will to carry out tasks that are obviously repulsive to them or to pointless military expeditions. (…) To my understanding, a Finnish soldier properly fulfills his assignment only if he feels the purpose he has to fight for, to shed his blood for, to be worth fighting for. For this reason, the Finnish soldier should not without cause be vexed with a too long duration of military service(…).”

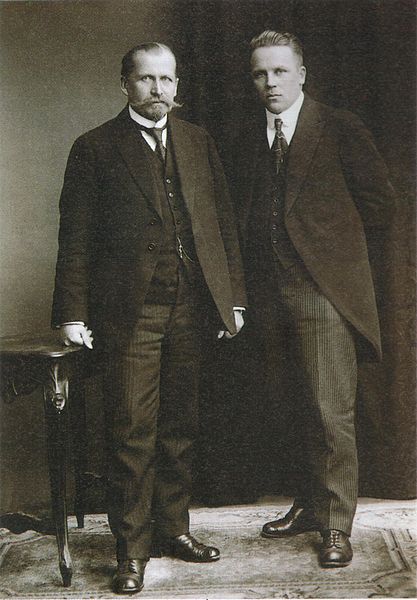

Kyösti Kallio (left) and Juho Niukkanen (right), 1920’s

Niukkanen was skilfully harnessing a certain image of Finnish character to his political objective of gaining support for a military service of just 12 months’ duration. Between the lines in Niukkanen’s depiction of ‘the Finn’, one can also read an acid critique of the upper-class military establishment, with its “foreign” traditions for military training, and the rumoured plans for a Finnish military expedition against St Petersburg led by General Mannerheim to topple the Bolshevik revolution.

(Niukkanen was heavily involved with the Agrarian Party from it’s early days and, a skilled organizer from his youth, would go on to become one of it’s leading figures. He was elected an MP in 1916 and serve almost without interruption until 1954. He became more influential than many of the Finnish Prime Ministers of the time and was well-known for his ability to bring down Governments. The Defence spokesman for the Agrarians, he would strongly support Mannerheim in his drive to build up the strength of the Finnish military through the 1930’s. He was a key figure in the “Red Earth” coalition of 1937 and went on to serve as Associate Minister of Defence together with Rudolph Walden during the Winter War. In the negotiations with the USSR to end the Winter War, he pressed strongly for Finland to continue fighting unless her territorial demands were met – Niukkanen viewed Mannerheim’s reports on the soldiers fatigue and Finland’s ability to keep fighting as unduly pessimistic).

An image of straightforward valiant soldiers of the people, excellent fighters but only for a just and necessary cause, is juxtaposed with an implied image of irresponsible, possibly too cosmopolitan and aristocratic officers who do not understand these men. In spite of the controversy over military systems, there was a new consensus and optimism among the non-socialist parties in the fall of 1918 regarding what Finnish soldiers could achieve. Although the Minister of War, Colonel Rudolf Walden, and others spoke warningly about the Bolshevik’s growing military strength, it was now generally accepted that Finland could and should defend itself militarily in case of a Russian attack. The events of 1917 and 1918 – the Russian revolution, the partial dismantling of the empire, the Russian civil war and the nationalist interpretation of the Finnish civil war as a war of independence from Russia – had evidently given Finnish decision-makers an image of Russia as a weak military power. Russian military might was by no means considered harmless, but the prewar conceptions in Finland of Russian absolute military advantage had been swept away – at least in the political rhetoric. The Agrarians especially, claimed that the Finns could beat the Russians superiority in numbers by superior fighting spirit and patriotic fervour.

The Temporary Law of 1919 – introducing “Universal” Conscription?

As it transpired, there was cross-party support in parliament for cutting the length of military training from 24 to 18 months, against the advice of military experts. In a still deeply divided society, an overly heavy military burden was evidently seen as a greater security risk by the MPs than a possibly insufficient number of troops in active service. Many members of parliament were anxious about the possibility that conscription might not produce docile patriotic citizens, but the opposite – rebellious sentiments in young men. The parliamentary committee for military matters stated, “during almost two decades, our people has lacked a military establishment, Wherefore the conscripts would think it exceedingly burdensome being compelled to leave their proper activities for two years. A duty that feels overly heavy, could again give reason for discontent with the national defence and the whole legal form of government.” The committee found it was “more important that the army is completely trustworthy than that it excels in technical skills”. Concerns were expressed that passing the law in a parliament where the workers had almost no representation risked undermining the legitimacy of both the conscription law and the conscript army. This problem of legitimacy was solved by passing the bill as a “temporary” conscription law. The government was requested to present parliament with a new conscription bill “as soon as circumstances permit”.

Parliament expressly instructed the government that the new bill should reduce both the financial burden of the armed forces and the time of service “as much as possible”. The 1919 Temporary Conscription Act regularised truly universal conscription for the first time in Finnish history. Parliament repealed the lottery procedure of the 1878 law as unequal and unjust. In practice, however, only about half of each age cohort was actually given military training around 1919–1920, due to medical reasons and large-spread dodging of conscription. As the internal situation in Finland stabilised, dodging became increasingly difficult, but the percentage of men never given military training for medical reasons remained high. In 1926–1930, a yearly average of 36% was still rejected at the call-ups. OTL, in 1932–1936 the share of rejected was 24%. About a third of those rejected were “sent home to grow up” and taken into service a year or two later, when their health or physical strength had improved. The number of Finnish men that did not receive military training slowly decreased, as living conditions improved through economic growth, from roughly a third of each age cohort in the mid-1920’s to one sixth in the mid-1930’s. Thus, even in the interwar era of “universal” conscription, a significant share of younger men as well as most older men never did perform military service nor undergo military training.

Socialist fears of “undemocratic” armed forces

As part of the policy of national re-integration pursued by centrist political forces – including broad amnesties for the socialist insurgents and social and land reforms to appease social tension – the Social Democrats were permitted to return to parliament in the spring of 1919 and did so in almost their pre-war strength. They received 38% of the popular vote and 80 seats out of 200. Their representatives immediately started pushing for military reform, claiming that Finland through the events in 1918 had found itself with an “old, imperial-style army” that not even the burghers were happy with. Having changed their mind since 1917, they now wanted a people’s militia similar to the Militia in Switzerland, which they asserted would be more affordable and more democratic than the Cadre Army. A militia, they claimed, would not threaten neighbouring countries the way a standing army always did, and would thus promote peace. Since most of its officers would be civilians, “for example folk school teachers”, there would be no breeding ground for a dangerous caste spirit among them. The suggestions of different Social Democratic MPs varied, from a basic military training period of four months to the militia exercising every Sunday and for one or two weeks each summer. Based on self-discipline, they explained, the militia system would be more motivating and meaningful for the conscripts, and better at arousing their patriotism than the cadre army system, which was based on external compulsion.

On the surface, this suggested Militia bore a remarkable resemblance to the Suojeluskuntas organisation cherished by the political right and centre. Yet the Social Democrats were highly critical of the Suojeluskuntas. They regarded them as a state within the state, an armed organisation with leanings to the extreme right and not necessarily controllable by the legal government. They disputed the Suojeluskuntas claim to political neutrality and accused them of meddling in domestic politics, forming a threat to democracy. Debating conscription in parliament in 1922, social democratic MP Jaakko Keto criticised both the Suojeluskuntas and the Cadre Army for being armed organisations threatening the republican form of government. A militia system was necessary for the preservation of the republic, he stated. The Social Democrats repeated much of their 1917 critique of standing armies in the early 1920’s. The long months of incarceration in the barracks resulted in loathing and reluctance towards military service, as well as moral corruption of the conscripts; “innocent boys are led astray into immorality, drinking, pilfering, theft and forgery”.

Oskari Reinikainen

Abuses of power and bullying of soldiers were well-known from Cadre Armies around the world, claimed MP Oskari Reinikainen, and they could never be checked because they were inherent in the system. The cadre system was not only a heavy economic burden for the citizens and incompatible with practical life – leading to loss of employment and difficulties to provide for one’s family – but also a danger to democracy. Since it was built on training the soldiers into unconditional obedience, there were no guarantees that these soldiers could not be used for reactionary purposes domestically and abroad – in other words, to put down strikes by Finnish workers or to attack Bolshevik Russia. Referring to the Russian and Prussian origins of the Finnish cadre system, the Social Democrats feared a military coup of some sort and frequently warned of the “undemocratic spirit” in the officer corps. Yet in spite of their loathing of the existing army system, the Social Democrats did not want working class men to be excluded from the civic duty of military service. They were enraged by a paragraph in the conscription bill of 1921 that allowed for the possibility of barring politically “untrustworthy” conscripts from military training and assigning them to labour service instead. These “Red paragraphs”, it was said, demonstrated how conscription was oppressive towards the working classes.

Yet somewhat inconsistently they also urged the bourgeoisie not to delude itself into thinking that the modern youth could be indoctrinated into unconditional loyalty to the government through military training. Due to the close contacts between the soldiers and the public in modern society, even a very long military service could no longer uproot the soldiers’ principles and produce the ideal bourgeois soldier. In 1924, the Social Democratic MPs exposed to parliament that an unofficial system for political classification of new recruits was being practiced in the armed forces. The “trustworthiness” of recruits was graded by the military authorities, in co-operation with the call-up boards and the local police and Suojeluskuntas, according to whether they were active members of the Suojeluskuntas and came from homes known to be “white” and patriotic, or whether they had affiliations with the worker’s movement. The Social Democrats called this system as practiced, a “caste system” that discriminated against soldiers from a working-class background and only produced “utmost bitterness among the soldiers and the whole working population”.

Eversti Lauri Malmberg (1927)

The Minister of Defence, ex-Jäger Colonel Lauri Malmberg, in his response admitted the existence of political classification without any further ado. However, he claimed it only registered communist sympathies among the conscripts and that this was necessary and normal practice in many other countries as well. According to historian Tapio Nurminen, it was in fact mainly communists who were actually classified as untrustworthy. The system was an attempt at ascertaining that the key military personnel given specialized education, ranging from machine gunners and artillery fire control men to noncommissioned and reserve officers, were completely “trustworthy personnel”; men who were active in or supportive of the Suojeluskuntas, brought up in homes known to be “trustworthy”, or otherwise known as “patriotic and loyal to the legal order in society”.

Comparing the Agrarian and Social Democratic Militiaman

In spite of many similarities, the Social Democratic and Agrarian versions of the militiaman differed in some important respects. The militiaman in his Agrarian version can be interpreted as expressing a firm belief in an essential warrior in Finnish men. This actually seems to apply to much of their subsequent arguments for shortening the military training period as well. The Agrarians’ vision of a militia system implied a view on warfare and military matters where the mechanical discipline and absolute obedience associated with the Cadre Army system was considered positively detrimental to military efficiency, since it ate into the conscripts’ motivation and patriotic enthusiasm. Dismissing extensive military training as unaffordable, morally corruptive and unnecessary in view of “the experiences of 1918”, their support for a militia system seems to have entailed a view of Finns as “natural warriors” who by sheer force of will, patriotism or protective instinct would fight ferociously enough to stop any aggressor. Whether this was seen as an inborn aptitude or something brought about by Finnish culture is not evident.

The Social Democratic version of the militiaman did not so much imply a warlikeness of Finnish men, but rather revealed a concern over how easily young men could be manipulated and impressed upon; a fear that military training could make class traitors out of young working men. If we are to judge by the Social Democrats’ rhetoric in parliament, they preferred the militia because it rendered more difficult inducing the soldiers with a false consciousness and making them act against their own class interests. The militiaman was bound up in civil society and adhered to its democratic values, but the young conscript incarcerated in the garrisons of a cadre army and isolated from civilian influences could soon be turned against his own class. There was also a connection to the Social Democrats’ concern over the financial resources devoured by the military. As they repeatedly pointed out, the tax money spent on defence was always money taken away from other important purposes; the first neglected area they listed was nearly always “culture” – that is, one can assume, the education and uplifting of the working classes to a higher level of civilisation, self-consciousness and social influence. Hence, merely the financing of the cadre army system dragged not only young men’s but the whole working class’ civic development in the wrong direction.

It is interesting that neither the Social Democrats nor the Agrarians, who both took the rhetorical position of speaking on behalf of the common Finnish people, brought up the issue of the language spoken among those officers of “the old Russian school” who, it was claimed, nourished an “undemocratic spirit” amongst them. It was perhaps natural that the rightwing parties wanted to emphasise national unity within the sphere of national defence. One might still expect that at least the mass parties in the left and centre would have pointed out that many of the most prominent members of the body of officers they criticised were also members of the old Swedish-speaking upper class. Yet for some reason, the frontlines in the politics of conscription never formed along the lines of language. One reason might have been that the Agrarians and especially the Social Democrats had imported much of their critical ideas about standing cadre armies from other countries, where the opposition between soldiers and officers was a class issue, not a language issue. Overall, the Social Democrats considered the language issue to be of minor importance for their political objectives in general. Another reason probably lay in the recent experiences of the civil war, where Swedish-speaking civil guards as well as officers had played a prominent role on the white side, side by side with Finnish-speaking troops. It was difficult for the Agrarians to explicitly criticise military heroes of the “Liberation War”. With the civil war in fresh memory, the military sphere was probably a relatively unlikely terrain for raising language disputes, whereas the war experiences made the antagonism between social classes difficult to keep out.

Why the Agrarians abandoned the Militiaman