Airbase 53, Eastern Karelia. March 1940

The cold was physical in it’s intensity at the isolated forward maintenance base deep in the forests, lakes and swamps of Eastern Karelia. A bone-chilling body-piercing soul-destroying unrelenting ever-present freezing cold that had been present for weeks now. A cold that drilled right down to the marrow of the exhausted, bone-weary ground crew as they worked on the planes. Spit and urine froze before it hit the ground, then bounced. Skin froze on contact with anything metallic. The sun shone palely, when it shone at all, through the meager daylight hours. The ground-crew manning the airbase were doing so with a minimum of tools and equipment, priority for transport went to fuel and parts for the aircraft, bombs and ammunition and food for the men and women who manned the remote airbase. Not much else. As they had trained for again and again in peacetime, the ground crew had built their own revetments for the aircraft, built their own shelters and accommodation, the one thing that made life bearable were their portable sauna-tents and the seemingly endless stockpile of vodka that the Soviet Airforce had left behind at the former Red Air Force forward airfield, captured in the first weeks of the war and put to immediate use as soon as it was far enough in the rear not to be actually on the front-line.

This was now one of the forward maintenance airfields to which the old and battered and shot up aircraft which the mechanics and airmen at the forward combat airstrips could no longer fix came to be cannibalized or repaired or modified. The airbase was isolated. Connected only by ice-roads through the snow to the rear. Whatever roads that had existed before the winter were buried under snow and mostly ran southwards towards the Front with the Red Army. The ground crew provided their own security. Finland had very few troops to spare to provide rear area security, certainly none for this small and isolated rear-area maintenance airbase near the White Sea. The men (and women, for almost 50% of the airbase personnel were women) guarded their own perimeter, sent their own patrols into the forest, slept with their rifles and submachine guns and pistols at their side. The Red’s had never attacked. Not even a raid. Not yet. No doubt they had other things on their mind. But for all its isolation, Airbase 53 was busy.

Aircraft flew in every day. Or were driven in on trucks in pieces. Despite having air superiority, the Ilmavoimat still took casualties, aircraft were still shot up or so badly worn out from the constant patrols and sorties that the mechanics and crews at the frontline bases couldn’t fix them up. When they arrived they were usually in bad shape. Shot to hell. Damaged from crashing on landing. Engines burnt out. Holes everywhere. Pieces missing. All the work the forward airstrips couldn’t handle, Airbase 53 did. Day and night. Seven days a week. Week in, week out. They took the planes, patched them, replaced parts, built parts, did whatever it took to get the precious aircraft back into the air again and back to the Squadrons that needed them desperately. Aircraft engines ran here all the time, snorting and choking, popping and howling, running low and slow, running to full power, screaming and growling and howling. It was a sound that was part of the men’s lives at any time of the short days or the long winter nights.

Aircraft engines these men and women knew. Intimately. They’d serviced them all. So it was strange that a faint intrusive hum of aircraft engines in the distance would gain their attention. They’d heard enough aircraft engines throbbing in the sky by now to know it wasn’t the neighbors come to pay them a visit, not that they did anymore. But it wasn’t an engine they were familiar with. Not the usual front-line fighters or the ground-attack aircraft that were their regular customers. And there was a subtle difference to this engine sound. It took an experienced man to detect it, but now, after three months of continuous war where they were outnumbered in the air and on the ground every hour of every day and they worked with engines day in and day out, the airbase was full of experienced men. Something about the sound drew the men and women one-by-one from their improvised workshops and the warmth of their shelters and their dugouts to peer into the cold winter’s sky.

The hum grew louder, louder still, and turned into synchronized thunder. A solid wave of sound that came from so many engines that it should have been garbled, discordant, grating even, but it wasn’t. And then they saw what some of them had begun to suspect they might see in the clear cold pale blue sky. Distant black twin-engined shapes. And with just that first glimpse they knew that this outfit was different from any other that had straggled into Airbase 53 in the eight weeks they’d been operational here. These aircraft were different, clearly recognizable as they grew rapidly closer. From the silhouette, unlike anything else in the Ilmavoimat, it was obvious that this was one of the famed Wihuri strike-bomber groups, and the watchers on the ground all wondered what they were doing, out here in the remoteness of Eastern Karelia.

Something grabbed the attention of the ground-crews, in a winter world where men and machines flew themselves to exhaustion and then staggered into the air yet again. And then again. And again. It was the way the aircraft were being flown. No one aircraft chased another. They flew in formation, tight, easily riding the thermals and the spinning slipstream of the great propellers and the vortices pummeling back from the wingtips. But other men, other pilots, also did that, so that wasn’t what called the attention of the men on the ground. There was some other invisible mark that etched this formation in the minds of the men watching. Men for whom damaged and shot up aircraft were an everyday sight. Men who lived with the ever-present bone-chilling soul-destroying cold and the knowledge that, whatever they did, the enemy still outnumbered them and would continue to do so whatever they did, whatever miracles they wrought, however good they were in combat. But despite all of that, the sight of these aircraft stirred a deep surge of pride in the watching men and women.

They flew with a precision that was so precise it was beautiful. And as the Wihuri’s continued their approach they could see ever more clearly just how beautiful that formation was. They flew as if one man touched the controls of all twenty aircraft, and the men watching from the ground, knowing that distance has a habit of glossing over imperfections, held their breath and wondered if closeness would mar what had grasped at their souls. But as the thunder of the Hispano-Suiza engines swelled and the machines enlarged, as the distance decreased, they saw that there were no imperfections and they were holding it in tight, all bunched in together as if they were flying in a parade with the air soft and untroubled. The widening eyes of the men and women on the ground were joined by unaccustomed grins and startled exclamations. Everyone on the base who could hear and see was looking into the sky, squinting into the glare as they watched the twenty bombers come in low, just above the tree-tops, until the thunder of their engines was a massive pounding wave of sound and the watching men knew that the twenty pilots at the controls knew how good they were and were trying to impart their pride and their confidence and there just wasn’t any better way to do it than what they were doing, rushing now with furious speed, hammering sound waves over the trees and the snow.

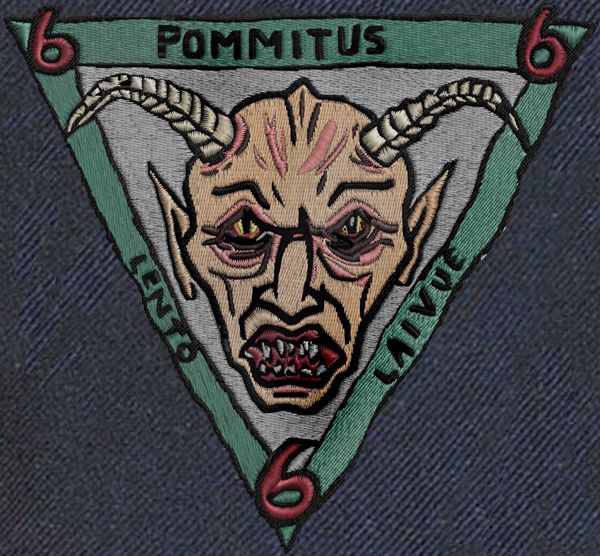

Pommituslentolaivue 666 uniform patch

The Wihuri’s flattened it out on the deck, smack down the runway, all twenty of them holding what by now everyone had to know was their combat strike formation, and as they swept by, just above the treetops, the watching men and women on the ground recognized the Squadron emblems on the aircraft and another collective gasp went up. Pommituslentolaivue 666, the “Devil’s Squadron”, the bomber wing who had led the attack on the Soviet Navy at Murmansk, who had attacked Soviet airbase after Soviet airbase, who had destroyed the Leningrad KV1 Works and who had led the revenge raid on the Leningrad People’s Military Hospital. The Ilmavoimat’s elite bomber squadron which had achieved the impossible again and again.

The Wihuri’s passed by in a storm of thundering engines before hauling up in a sudden wild steep climb, the first twelve bombers in a vee of three vees, then the second eight and they were really hauling coal now, flashing before the sun as they rolled smoothly, beautifully, out of their climbing turns, their thunder more ragged now. They seemed to ease up into an impossible floating movement as the pilots let up on the power and from every bomber, virtually at the same moment, flaps were sliding back and down from the wings, the two legs of the landing gear of each bomber jutted stiffly into the wind, and as the watchers below strained to make out more details, the first four Wihuris’ had curved gracefully, like fighters, through the pattern of the airfield, and rolled around, sliding into final approach still in tight formation and staying tight and it was now obvious that they were going to land like that.

Landing in formation wasn’t something you did at Airbase 53. Maybe before the war started, but not now. The runway was all screwed up from the fighting and from the early Ilmavoimat bombing raids that had gotten through before the front passed over as the Maavoimat had advanced. It wasn’t that wide, it just wasn’t the place to pull off this kind of super-precision crap, but no-one had told the pilots up there that, and they were doing it, and every man on the ground who knew what the inside of a cockpit looked like knew also that the manifold pressure gauges and the revolution per minute and fuel pressure and oil temperature and the rate of descent and the air-speed needles and the gyro compasses in each plane were dead-on, every set of instruments in each plane like those of it’s companion aircraft. If the instruments worked of course.

They came sliding down their invisible rail in the sky, glued together, all of them shimmering in the cold blue air, and as the runway came up to meet them the pilots set their trim just right and they flared, control yokes easing back with practiced skill, without deliberate thought, for this was rote and instinctive motion and the noise of each bomber came higher as they bled off air speed and ghosted their descent to earth. And on the ground, the watchers wondered what in hell’s name Pommituslentolaivue 666 was doing out here, down near the Syvari.

Excerpt from “Quality is our Strength. Suomen Ilmaivomat. A history of the world’s most remarkable air force 1918-2008”

Excerpt from “Quality is our Strength. Suomen Ilmaivomat. A history of the world’s most remarkable air force 1918-2008” by Prof. Dr. Michael Wolffsohn, Department of History at the University of the Bundeswehr at Munich, Berlin/Munich/Opladen 2010, pp. 311/312

“[…] Even today, the official crest of what has come to be the most efficient and respected deep-strike special operations bomber squadron in the world, surpassing in reputation even the famed USAF stealth bombers and the German Luftwaffe’s JaBoG z.b.V. 71 which incidentally was formed after the founding of the FRG modeled on the 666th -the squadron’s performance against the Soviet Union in general and the Third Reich in particular must really have made an impression – strikes certain more religiously inclined people as strange, even offensive.

Originally sketched free-hand in a rare moment of quiet shortly after the commencement of hostilities between the SU and (as it then seemed) little defenceless Finland by then-Yliluutnantti Erkki Tempponen, the B/N of the squadron CO’s plane (who was unfortunately dyslexic and to the amusement of the rest of the squadron personnel, always had problems with his spelling – and as a result was the butt of many jokes – the original drawing reflected this, but while the spelling was correct on almost every aircraft in the Squadron, Tempponen’s was painted with his original spelling to the amusement of everyone, including Tempponen, who had long learned to live with the problem).

The original unit patch was drawn by the unfortunately dyslexic Lt. Erkki Tempponen

The Finns are not known for being a particularly light-hearted people so especially compared to other unit crests in other countries of that time and even Finland itself which often displayed a humorous slant, at the same time taking into account the dire situation Finland found itself in and the unit’s exhausting round-the-clock cycle of extremely dangerous strikes deep behind enemy lines, the crest was especially grim. The original sketch – black ink and color pens – survived the war and was included in the official unit war diary. It was accepted in its original form and, in a rather more polished and exact version, found its way to the fuselages of every plane of the unit and the flight suits of the unit’s members.

Notably, “666” unit patches are a highly coveted and sought-after souvenir in most European and North American Air Forces. Below is a scan of the original paper sketch on display at the Finnish Winter War museum in Tampere”

666 Squadron – The Movie

Supreme Headquarters, Mikkeli. xx March 1940

To be continued…….

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

2 Responses to Pommituslentolaivue 666 and the death of Colonel-General Shtern