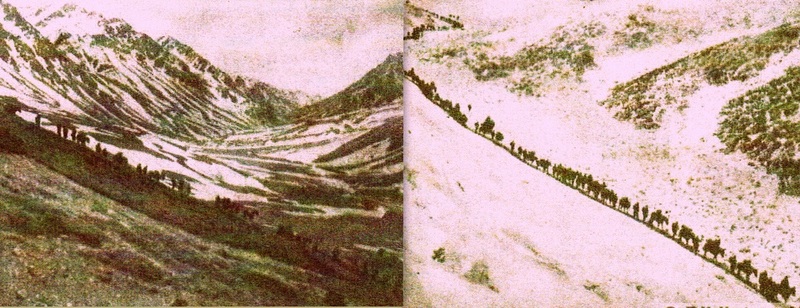

In late February 1940, a small Brigade sized unit of 4,500 South American volunteers, most of whom were from Argentina but with one Battalion of Chilean mountain infantry, arrived at Lyngenfjiord on ships from Buenos Aires. This was the Regimiento Bolivar “Cazadores de Montana.” To those from elsewhere, South America is not often thought of as a continent whose soldiers are experienced and trained in winter warfare. However, this belies the obvious – the backbone of South America is the Andes mountain range – which also runs along the borders of a number of countries, including Argentina and Chile, the two countries with whom we are most interested as there are where 98% of the south American volunteers who fought in Finland came from. With much of their border areas being mountainous, both Argentina and Chile had early on trained sizable specialist units in mountain warfare, often in extreme conditions.

…..both Argentina and Chile had early on trained sizable specialist units in mountain warfare, often in extreme conditions

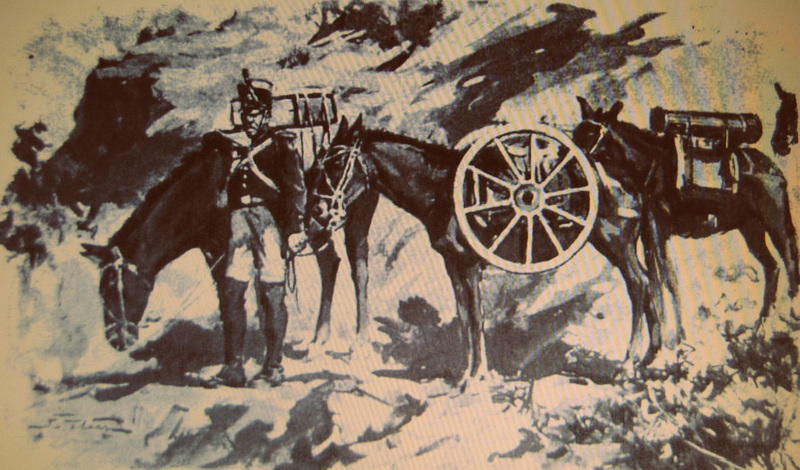

To find the origins of the Argentine mountain troops, we must go back to the South American wars for independence. More precisely to the Chasseurs of the Andes founded by the famous Argentine liberator, General Jose de San Martin, for possibly the largest military operations and logistical maneuvering on the South American continent. An entire army under his command crossed the Andes mountains in the style Napoleon at Saint Bernard (Alps), hence the name “Army of the Andes”. Specifically, this body of “Hunters of the Andes” (Chasseurs of the Andes) was wearing a uniform inspired in part by the British Light Companies of the Napoleonic Wars.

The origins of the Argentine mountain troops …(lie in) ….. the Chasseurs of the Andes founded by the famous Argentine liberator, General Jose de San Martin

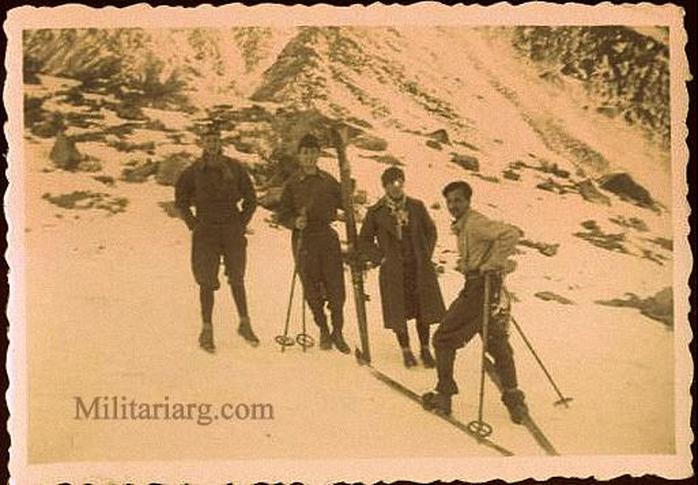

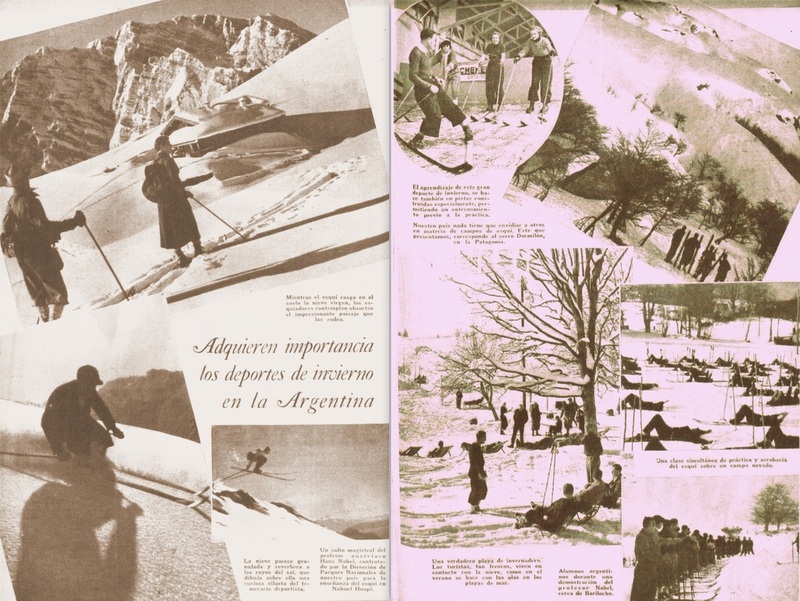

In WW1, mountain warfare and combat tactics gained prominence, particularly in the fighting along the Austrian-Italian front. Argentina, a country with a long Andean border and ongoing tensions with Chile, decided to send officers and military attaches to countries like Italy and Germany where mountain warfare was studied and particularly to Italy, where mountain warefare units were maintained through the inter-war years. Argentine officers received technical training and logistics training in the field of mountaineering, Military and Sports skiing skills were also developed in these years.

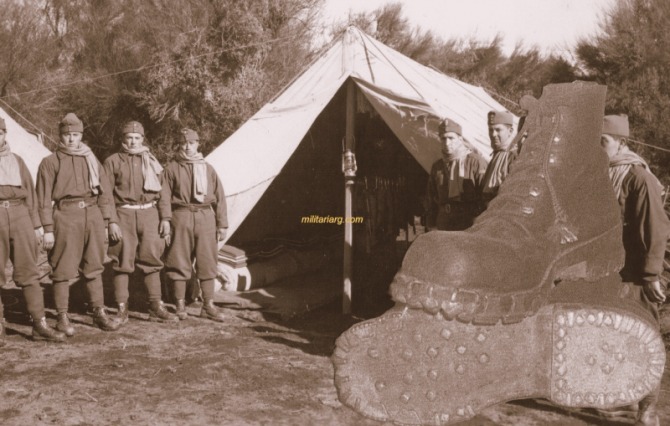

Both Argentina and Chile placed a strong emphasis on mountain warfare – in the 1920’s and 1930’s Argentina had a Mountain Warfare School outside Mendoza in the Andes, and Chile maintained a similar training camp on her side of the Andes. In the late 1930’s the Argentine Army began in earnest to modernize and update the doctrine and tactics of mountain warfare and promising young officers were often given the opportunity to train overseas in Italy before bringing their new-found skills together with knowledge of recent developments back to the Argentine Army Mountain Warfare School in Mendoza..

Similar to the uniform of late 1939, the Model 44 Uniform (R.R.M.44), Argentine skier with snow camo. Painting by Argentine artist Marenco . Right: Mountain troop officer with model 46 uniform in earthy brown color.

Important figures in Argentine history were sent on these educational trips – young officers such as Edelmiro Farrell, who trained as a staff officer at the Italian Alpine military school of Aosta and who would later in Argentina found the infantry regiments.

El teniente coronel Edelmiro J. Farrell, commandante en jefe el destacamento de Montana Cuyo…. Farrell would later become President…

Training at the Argentine Mountain Warfare School was extremely tough, and instructors were expected to be among the best Officers in the Argentine Army. To qualify as a Mountain Warfare and Military Ski Instructor was no sinecure.

The footwear of the Argentine mountain troops was not very different from other mountain troops of the era. It was basically a short waterproof combat boot in black with a three-layered sole that had hobnails, edge cleats and toeplates.

Machinegun training. Mountain troops had to be able to bring their heavy weapons with them and use them accurately and efficiently in extreme conditions with challenging logistics – training that proved very applicable in the Winter War, where the Argentine and Chilean volunteers proved to be some of the best of the non-Finnish troops at fighting under the harsh conditions of an Arctic Winter.

The following report on the training of Argentine mountain artillery units was originally published in the US military journal “Tactical and Technical Trends”, No. 1, June 18, 1942 and serves to illustrate Argentine military capabilities at the approximate period of time in question.

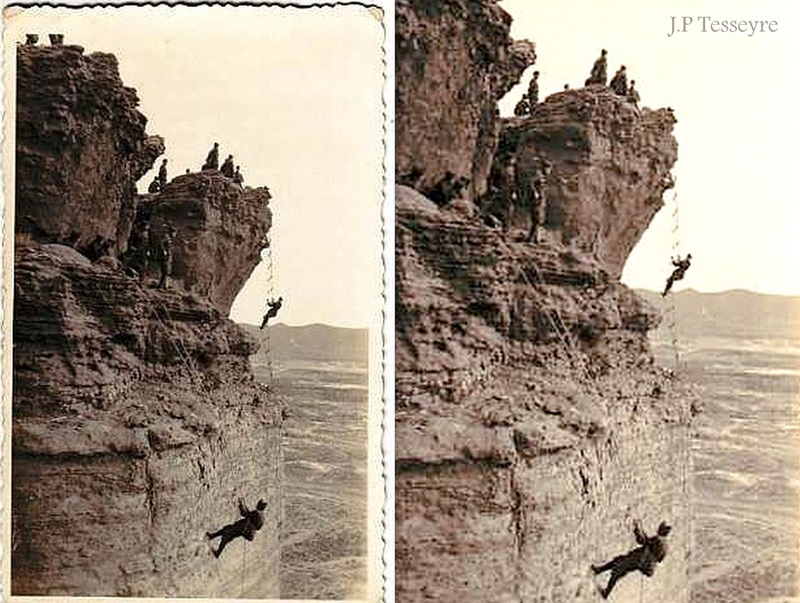

“Argentine Mountain Artillery Training” from Tactical and Technical Trends

A demonstration was given by a 75 mm mountain artillery battery; all the men taking part were of the class of 1920 and therefore had been in the service a little over one year. The exercise was held in the foot hills about two miles west of Mendoza. The terrain in this region is very rough and rocky with no vegetation except cactus and small bushes. There are many steep slopes, slides, and chasms. All pack mules were led by men dismounted. One gun was taken in pack to the top of a hill over a narrow, knife-edge ridge which was so steep that dismounted men assisted the mules by hauling on ropes tied to each side of the packs. This gun was eventually placed in position on top of the hill. Another crew hoisted its loads to the top of a cliff by hand, first using rope ladders for the personnel. The loads were then taken across a deep arroyo on a rope cable with pulleys. The personnel also crossed in this manner and the gun set up on the other side. It was explained that the rope ladders and cables had previously been placed in order to save time. Nearly every pack carried a coil of heavy rope, and several rope cables were also carried. The battery detachment scaled a nearly vertical cliff on foot in the Alpine style to establish an observation post on a high hill. Communication equipment consists of telephone and radio. All these activities were conducted simultaneously.

Comments by observer: This demonstration is the best I have seen of Argentine army activities. Although rehearsed many times, as could be seen by the appearance of the ground, it presented a true phase of peace-time garrison training. The troops were in their every-day work uniforms and there was a total lack of parade ground atmosphere. The equipment was well worn but kept in serviceable condition. The guns were clean and working parts oiled. All in all, I was very favorably impressed with the efficiency by all ranks. (M/A Report, Argentina, No. 7809.)

After training at altitude in the mountainous terrain of the Andes, the low altitude and almost flat terrain of Finland in winter seemed somewhat similar to Paradise for the tough Argentine soldiers – until they met the Russians….. “los rusos no eran niños chilenos de conejo” (“the Russians weren’t chilean bunny-boys”) as one Argentine soldier later said.

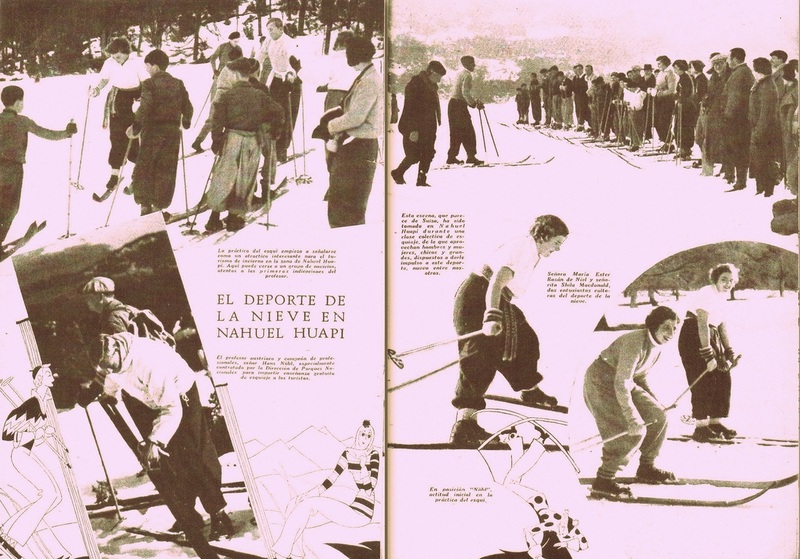

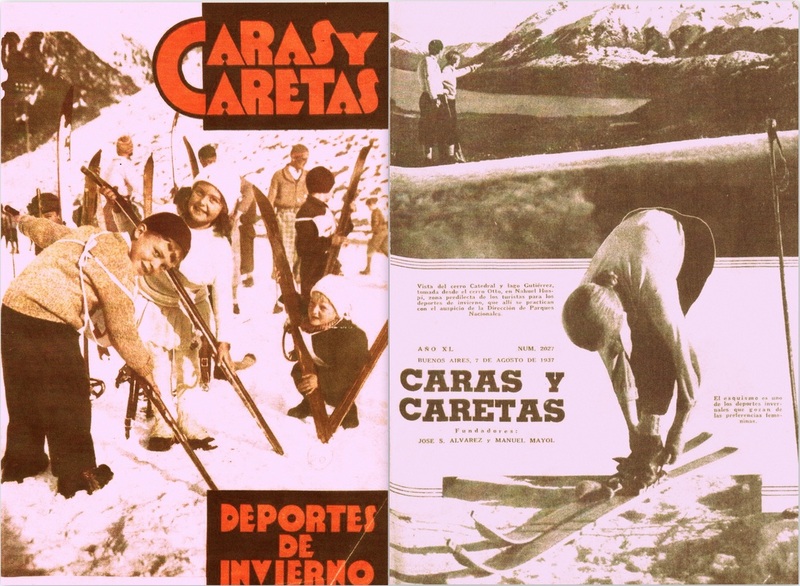

In the inter-war decades of the 1920’s and 1930’s, sking was not just a military pastime but also became a popular recreational activity for those well off enough to be able to afford the cost. Mendoza was not only used for military training, but became a popular ski resort for well-heeled Argentinos.

Returning now to the Argentine military, with a population (in 1938) of 12,762,000: in 1939, Argentina fielded the largest and most powerful armed forces in all of South America. Military service was compulsory for all males capable of bearing arms and between the ages of 20 to 45 years old (one year of which was in the active service and 24 years in the reserve). In 1938 the army numbered 47,467 full-time personnel, organized into five divisions based on military districts. Aside from these five divisions, there were also two cadre regiments of mountain infantry, three cavalry brigades, and several independent and service detachments. The training was generally modeled on that of the German army. The Argentine Navy was the 8th largest in the world during this period and was starting a period of considerable expansion. Personnel of the naval forces stood at 12,000 (including a 450-strong coastal artillery corps); its equipment included four line vessels (two of them old), two coastal defence armoured ships, three light cruisers, 16 destroyers, and three submarines, with a collective displacement of 107 000 tonnes. The main naval bases were at Puerto Belgrano and La Plata. The air force, prior to 1944, did not constituted a separate branch of the armed forces but instead various units of the air force formed integral parts of either the army or navy. In 1937 the army had 106 airplanes while the navy had 46. In 1939 there were three aviation groups, each group was composed of one fighter and three recon mini-groups (a mini-group was formed from two flights). The Argentinian armed forces served as a powerful weapon in frequent internal struggles for power (especially in the 1942-1945 period), and participated in numerous military coups.

Chile’s army too was not insubstantial – it was based on a national militia system that emphasized total mobilization of the country’s menpower. All citizens capable of bearing arms were required to serve in the armed services in case of a general mobilization. In 1939 there were three military districts which were obligated to raise a whole division in case of hostilities (in 1940 one more military district was created). The army consisted of three cadre divisions of the military districts (four from 1940) and a cavalry division (each division included three brigades). In the early 1940’s each of these five cadre divisions included the following units: 12 regiments andfour mountain infantry battalions, six cavalry regiments, four field artillery regiments, one heavy artillery group and six mountain artillery groups, four engineer battalions (pontoons, sappers, and communications), one regiment of railway troops, one regiment of heavy bridge engineers, two mixed detachments, and other units. On full mobilization the strength of the armed forces would reach in excess of 725 000 troops. The navy possessed eight large destroyers, nine submarines, two coastal defence ships, a surveying ship, a submarine depot ship, two oil tankers, and miscellaneous training and auxiliary vessels. It had some 8 000 personnel.

Thus, as we can see, the armed forces of both countries were substantial and with conscription, all male citizens had generally undergone a year of full-time military training. In addition, each country had sizable cadres of mountain warfare troops, with many more reservists who had undergone mountain warfare training during their period of compulsory military service.

Economically, despite the effects of the Great Depression, Argentina was still a wealthy country. Through the 1920s, Argentina had been the “breadbasket of the world” – and the world’s sixth wealthiest nation. In 1929, Argentina had had the world’s fourth highest per capita GDP – largely built on the export of wool and meat. British investment in Argentina in the last half of the nineteenth century had been significant and as the British built railways stretched out across the country, both the cattle and sheep industries had flourished, making Argentina’s fortune through the exporting of both wool and meat. Refrigeration ships were invented in the 1870’s, enabling meat to be shipped in bulk to the expanding industrial countries of Britain and Europe. British immigrants formed a sizable and influential Anglo-Argentine community – the largest of any country outside the British Commonwealth. The world depression following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 devastated export markets but the collapse of international trade also led to internal industrial growth focused on import substitution, leading to a greater economic independence.

Argentine politics of the 1930s were essentially a conflict between the demands of an increasingly militant urban labour movement and the Conservatives, still powerful in the provinces and with allies in the armed forces. Through the 1930s a series of military backed governments, dominated by the Conservatives, held power; the Radicals were outlawed and elections were so fraudulent that it frequently happened that more people voted than were on the register. Yet the armed forces themselves were disunited: while most officers supported the Conservatives and the landholding elites, a minority of ultra-nationalist officers, inspired by developments in Europe, supported industrialization and the creation of a one-party dictatorship along fascist lines. Internal political conflict increased, marked by confrontation between right-wing fascists and leftist radicals, while military-oriented conservatives controlled the government. Though many claimed the polls to be fraudulent, Roberto Ortiz was elected president in 1937 and took office the next year, but due to his fragile health he was succeeded by his vice-president, Ramón Castillo. Castillo effectively took power in 1940; he formally assumed leadership in 1942.

Jaime Gerardo Roberto Marcelino María Ortiz Lizardi (September 24, 1886 – July 15, 1942) was President of Argentina from February 20, 1938 to June 27, 1942

Photo, Left: Jaime Gerardo Roberto Marcelino María Ortiz Lizardi (September 24, 1886 – July 15, 1942) was President of Argentina from February 20, 1938 to June 27, 1942. Ortiz was born in Buenos Aires and graduated from the University of Buenos Aires (after participation in an unsuccessful revolution in 1905) as a lawyer. He became active in the Radical Civic Union and was elected to the Argentine National Congress in 1920, serving as Minister of Public Works from 1925 to 1928. He supported the revolution of 1930 and served as Treasury Minister from 1935 to 1937. In the presidential elections of 1937, he was the official government candidate and won, though the opposition accused him of participating in electoral fraud. Soon after becoming president, Ortiz became seriously ill with diabetes and in August 1940, he gave up his powers to vice-president Ramón Castillo. He resigned a few weeks before his death. Ortiz was a supporter of Britain and France but due to the armed forces being largely Germanophile, Argentina maintained a neutral posture on the outbreak of WW2.

While the Argentine army was highly Germanophile, this did not involve a rejection of democracy but rather an admiration of German military history and military professionalism. This, combined with an intense Argentine nationalism, influenced the main stance of the army towards Britain and Germany on the outbreak of WW2: neutrality, with the perception of the war being as a conflict between foreign countries with no Argentine interests at stake. Only a handful of military took the Germanophilia to an actual support of Adolf Hitler. Argentina did however have an influential Anglo-Argentine population with major business and agricultural interests – and Britain was a major export market for Argentine meat and wool and would remain so throughout WW2. However, there WAS a strong Communist Party in Argentina which was oriented towards supporting the USSR. On the outbreak of WW2, the Argentine Communist Party toed the Stalinist line and opposed any support to Britain.

On the outbreak of the Winter War, in Argentina and Chile as elsewhere, support for Finland among the population at large was strong – although in South America, news of the attack on Finland by the Soviet Union had more impact in those countries with strong ties to Europe – primarily Chile, Argentina and Uruguay, all of whom had large immigrant populations who still had close ties to Europe.

We have previously mentioned that numbers of promising young Argentine Army Officers were sent to Europe, and particularly to Italy, to go through Italian Mountain Warfare and Ski Training schools. In 1939, one such officer was none other than Major Juan Peron who was sent along with other Argentine officers to the Merano Tridentine Alpini Division for military training and training in ski mountaineering we well as to observe other Italian military units and to visit other European countries. Perón had begun his military career shortly after WW1 and had made somewhat of a name for himself in1920 by resolving a prolonged labor conflict at La Forestal, a leading Argentine forestry firm. He went on to earn instructor’s credentials at the Superior War School, and in 1929 was appointed to the Army General Staff Headquarters. Perón married his first wife, Aurelia Tizón (Potota, as Perón fondly called her), on January 5, 1929. After supporting the wrong General in a military coup in 1930, Perón was banished to a remote post in northwestern Argentina, although this did not harm his career.

He was promoted to the rank of Major in 1939 and named to the faculty at the Superior War School where he taught military history. He served as military attaché in the Argentine Embassy in Chile from 1936 to 1938, after which he returned to his teaching post. His wife was diagnosed with cancer that year, and died on September 10 at age 29; the couple had no children. Perón was then assigned by the War Ministry to study mountain warfare in the Italian Alps in 1939 – an assignment which proved fortuitos for the up and coming young officer. He also attended the University of Turin for a semester and served as a military observer visiting Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Albania, Yugoslavia, and Spain. He also studied politics, including Italian Fascism, Nazi Germany, and other European governments of the time, concluding in his summary, Apuntes (Notes), that social democracy could be a viable alternative to liberal democracy (which he viewed as a veiled plutocracy) or totalitarian regimes (which he viewed as oppressive).

Perón was in Finland as an observer with the Italian Alpini Division for the planned winter exercises in late 1939 when tensions escalated and Mussolini placed the Alpini and the other Italian units in Finland for the exercises at the disposal of the Finnish government and military command should war break out. Very much the Argentine man-on-the-spot, Perón was caught up in the enthusiasm of the Italians in support of Finland and made his own very public plea to Buenos Aires for Argentine governmental and military support for the dispatch of volunteers to Finland. The arrival of Maureen Dunlop, the highly photogenic Anglo-Argentine female pilot, as a volunteer in Finland made the front pages of every newspaper in Argentina – and joining her on the front page was the handsome young Major Juan Perón with an impassioned article supporting the dispatch of Argentine volunteers to fight in Finland – and himself volunteering to remain in Finland and fight as their commander.

Photo, Left: Photos of Major Juan Perón were splashed across the front page of every newspaper in Argentina alongside his impassioned plea for Argentine Volunteers to come to Finland. The image of Perón as a gallant combat commander of heroic Argentine soldiers fighting in Finland assisting the heroic Finns in their epic war against the Russians would serve Perón well in the years to come….

Support among conservatives in Argentina was strong, while the Soviet-oriented Communist Party expressed strong opposition. The military themselves were strongly anti-communist and the outspoken Argentine Communist Party support for the USSR, and vituperative criticism if Finland, merely served to overrule their instinctive reaction to remain neutral and to instead at least tacitly support Finland. The Ortiz government acquiesced, as it did on many issues, to the wishes of the military and announced officially in late December 1939 that Argentina would permit volunteers to travel to Finland to assist the Finns with official Argentine Government backing – and that former Major, now Teniente-Coronel Juan Perón, was appointed to lead the Argentine Volunteer Force into battle at the side of the gallant soldiers of Finland.

The response in Argentina surpassed the expectations of the military, the government and of Perón. Argentines by the thousands volunteered and, as elsewhere, support for Finland was strong, particularly among the more conservative members of Argentine society. The strong communist movement in Argentina continued to strongly denounce any assistance to Finland as being against the interests of the working classes, as represented by Stalin and the heroic workers of the Soviet Union and the comrades of the Red Army. The Army in turn announced that all ranks would be permitted to volunteer and within days, at first a Battalion and then two Battalions plus support units for a Brigade had been selected and were assembled just outside of Buenos Aires. These men were hastily transported southwards to Mendoza for refresher training while shipping was organized. At the same time, civilians worked to organize non-military assistance for Finland – the first example of which was a shipload of frozen Argentine beef which was to be dispatched together with the shiploads of volunteers and enormous quantities of Argentine wine donated by well-wishers.

In early January 1940, the Chilean government officially approached the Argentines and requested that a Battalion of Chilean mountain infantry volunteers be sent to Finland as part of a joint Argentine-Chilean volunteer brigade. It was at this stage that it was decided to name the volunteers the Regimiento Bolivar – the early Argentine inclination to opt for Regimiento San Martin after the Argentine national hero being deemed liable to spark a disagreement with the Chileans – and Bolivar was sufficiently acceptable that all volunteers of both nationalities would accept this name for the unit. Some three weeks later the Volunteers had been joined by the Chileans and all 4,500 men embarked on ship after a parade through Buenos Aires, where they were given a grand farewell.

Argentine Volunteers of the Regimiento Bolivar in snow camo march on parade through Buenos Aires prior to embarking on ship for Finland. January 1940.

Fighting Knife of the Cazadores de Montana – many of the cazadores would return to Argentina with Finnish puukko knives which they had bought to replace the argentine-army issue knives. This founds it’s way into the mythos of the cazadores and today’s Argentine Army cazador companies maintain a tradition of all men carrying a Finnish “Puukko” knife.

There would be one further piece of tangible military assistance from Argentina to Finland. Argentina had ordered 12 75 K/40 artillery pieces from Sweden. With the dispatch of the Regimiento Bolivar to Finland in January 1940, the Argentine Government donated all 12 guns to Finland, merely asking that they be assigned to the Regimiento artillery battery, the personnel for which were amongst the Argentine volunteers.

The 75 K 40 was manufactured by Bofors for the Swedish Army and for export based on a Krupps design. The main export customer was Argentina, who had ordered 12 guns. All 12 were donated to Finland by the Argentine Government and were issued to the Field Artillery of the Regimiento Bolivar. Three of the guns were destroyed in combat. After the Winter War ended, the remaining 9 were returned to the Maavoimat before the volunteers returned to Finland and Chile.

Speaking of Chile, support for Finland was as strong in Chile as elsewhere and large amounts of money were raised. This resulted in the purchase from Sweden of what would be come known as the “Chilen tykki” – the “Guns of Chile.” In the mid-1920’s, Swedish Bofors had developed a 105-mm howitzer for export sale. The Netherlands purchased 30 of these howitzers to be used in its colonies at East Indies. However World War 2 changed plans: the Swedes found themselves in desperate need of more field artillery and so, in 1939 the Swedes confiscated 32 howitzers which had been ordered by the Netherlands and Siam (Thailand) but not yet delivered.

The Bofors-manufactured 105 H/37 howitzer – 24 of these were paid for by Chile and supplied to Finland – they became known as the “Chilen tykki” – the “Guns of Chile.” The Swedes kept 8 for some months, but in May 1940 would transfer these 8 to Finland as well.

The 105 H/37 howitzer had a split trail with hinged spades, gun shield and wooden wheels with steel hoops. Later in the war the old wheels were replaced with new rubber tired wheels with a built-in brake system. The recoil system below the barrel was of the typical pneumatic/hydraulic kind. The breech system with a semi-automatic vertical sliding breech block (after firing a shot the system removed the used cartridge case and readied itself for loading the next shot) used in the howitzer allowed quite a high rate of fire – 10 shots/minute. The muzzle was equipped with a perforated muzzle brake and the sight system was the typical dial sight. The barrel was of autofregated structure (in other words: it didn’t have sleeves). The howitzer was suitable both to be horse-towed and for motorised towing. Ammunition was cartridge-seated type with 6 propellant charge sizes. The limber used with the howitzer contained four shots. In service with the Maavoimat, the “Chilen tykki” would be used by Finnish artillery regiments throughout the Winter War and later in WW2.

An artillery piece of the Regimiento Bolivar’s artillery battery going into action against the Red Army, July 1940. The professionalism of the Argentine Army artillery volunteers in the Winter War saw them very quickly acquire Maavoimat artillery techniques and make very effective use of these over the months of heavy fighting.

Soldiers of the Regimiento Bolivar in Finland initially built snow shelters as per Argentine Mountain Warfare training. Their Finnish liaison officers soon taught them techniques better adapted to the Finnish winter conditions.

“Soldiers of the Regimiento Bolivar led by Teniente-Coronel Perón moving up to the front to block a Red Army breakthrough. The confidence of the cazadores in their ability to put a stop to the Bolshevik attack is evident in their cheerful faces and swinging stride as they go into battle yet again….” (from the Buenos Aires “La Vanguardia” newspaper 28 July 1940)

Teniente-Coronel Juan Perón in Finland: signed photograph from the photo album of his Maavoimat Liaison Officer

Of his time in Finland in command of the Regimiento Bolivar, Teniente-Coronel Perón would later write: “The terrain, the soldier, the fighting patterns, the climate and untamed nature of the Finnish forests; everything seemed to speak to us in a different language. The forest of Finland lends an atmosphere of surprise and the unexpected to the battle; in it, everything superfluous or apparent disappears and the battle leader must impose oneself. There one must be more than one seems. It was the true command school.” In another passage Peron writes, “The art of command is intuitive but it is perfected by exercising it. Fighting in the winter war had needs that went beyond normal commands. One must love the soldier and the comrade in battle to be loved by them in return; an officer and a leader in battle must know the mens needs and share their hardships, their fatigue, their sacrifices; win their esteem and their confidence with your example.” Of the cazadores, Perón writes, “We of the Regimiento Bolivar had to simultaneously combat with three enemies: the terrain, the climate and the enemy, our missions were always the most difficult, it was the most complicated tactical problems, the material means less potent and the actions were fought and won by the initiative and courage in battle of all….”

After the Winter War ended, Perón would return with the volunteers to Buenos Aires, where he was immediately placed in command of the Argentine Army Mountain Warfare Training School. This was in part a deliberate move by the Army command to remove Perón from Buenos Aires – he was already recognized as a “political” officer and with his high profile in Argentine newspapers as the “Hero of the Winter War”, his popularity had soared.

Cazadores of the Regimiento Bolivar on parade in Finland, November 1940, immediately prior to returning to Argentina and Chile. The men of the Regimiento Bolivar performed many dangerous missions and fought to great effect throughout the Winter War under the command of Teniente-Coronel Juan Perón. In the last great battles of July and August 1940 the unit took heavy losses but would nevertheless continue to fight effectively through to the end of the war.

Photo, Left: Lieutenant Colonel Juan Perón in the center for mountain instruction in Mendoza upon his return from Finland. (He is dressed in a dark khaki colored open jacket and an earthy brown cap, specialty uniform for the Argentine mountain troops). Photo from and early 1941 Buenos Aires newspaper. Despite being stationed in Mendoza, Perón remained in the public eye.

Promoted to Colonel, Perón would play a a significant part in the military coup by the GOU (United Officers’ Group, a secret society) against the conservative civilian government of Castillo (who as Vice-President had suceeded Ortiz on his death in 1940). At first an assistant to Secretary of War General Edelmiro Farrell, Perón later became the head of the then-insignificant Department of Labor. Perón’s work in the Labor Department led to an alliance with the socialist and syndicalist movements in the Argentine labor unions. This caused his power and influence to increase in the military government. In Finland, Perón had also met a number of times with Finnish politicians and after the war ended, had spent his remaining time in Finland looking at the Finnish poltical model, nationalised and state-owned industries and the labor and social welfare legislation of the country. The obvious successes of these in raising the living standards of the Finnish workers had impressed him and thus when, after the coup, socialists from the CGT-Nº1 labor union, through mercantile labor leader Ángel Borlenghi and railroad union lawyer Juan Atilio Bramuglia, had made contact with Perón (and fellow GOU Colonel Domingo Mercante) he proved receptive to their approach and their ideas.

They established an alliance to promote labor laws that had long been demanded by the workers’ movement, to strengthen the unions, and to transform the Department of Labor into a more significant government office. Perón had the Department of Labor elevated to a cabinet-level secretariat in November 1943. Following a devastating earthquake which claimed over 10,000 lives, Perón became nationally prominent in relief efforts. The Junta entrusted fundraising efforts to Perón, who marshalled celebrities from Argentina’s large film industry and other public figures. The effort’s success and relief for earthquake victims earned Perón widespread public approval. At this time, he met a minor radio matinee star, Eva Duarte. Following President Ramírez’s January 1944 suspension of diplomatic relations with the Axis Powers (against whom the new junta would declare war in March 1945), the GOU junta unseated him in favor of General Edelmiro Farrell. For contributing to Farrell’s success, Perón was appointed Vice President and Secretary of War, while retaining his Labor portfolio.

As Minister of Labor, Perón established the INPS (the first national social insurance system in Argentina), settled industrial disputes in favor of labor unions (as long as their leaders pledged political allegiance to him), and introduced a wide range of social welfare benefits for unionized workers. Leveraging his authority on behalf of striking abattoir workers and the right to unionize, he became increasingly thought of as a presidential candidate. On October 9, 1945, Perón was forced to resign by opponents within the armed forces. Arrested four days later, he was released due to mass demonstrations organized by the CGT and other supporters.

His paramour, Eva Duarte, became hugely popular after helping organize the demonstration; known as “Evita”, she helped Perón gain support with labor and women’s groups. She and Perón were married on October 2, 1945. Perón would be elected President in 1946, largely on the basis of his stated goals of social justice and economic independence – but his status as a genuine war hero from the Winter War certainly did him no harm. The rest, as we know, is history…..

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

One Response to Regimiento Bolivar “Cazadores de Montana”