Not to be outdone by the larger Dominions, the small British african colony of Rhodesia sent an entire Battalion of volunteers to Finland, the Selous Battalion. These Rhodesians of the Commonwealth Division in the Winter War served and fought well, as did their compatriots throughout World War Two and afterwards.

In 1939, the Colony of Rhodesia and Nyasaland consisted of what are now three countries – Malawi (Nyasaland), Zambia (Northern Rhodesia) and the failed state of Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia). The Rhodesians of that time were proud of their military heritage – Rhodesia had first been colonized only 50 years previously, starting in 1890 when the Pioneer Column, a group of white settlers protected by the British South Africa Police (BSAP) and guided by the big game hunter Frederick Selous, trekked through Matabeleland and into Shona territory to establish Fort Salisbury (now Harere).

In 1893-1894, the Rhodesians would defeat the Matabele in the First Matabele War. In 1896-97 the Ndebele would rise against the colonial government in the Second Matabele War which resulted in the extermination of nearly half of the British settlers before the Matabele were defeated. The territory north of the Zambezi was the subject of separate treaties with African chiefs and was administered as Northern Rhodesia from 1911 (now Zambia) while the south became known as Southern Rhodesia and became a self-governing colony in 1923.

Economically, Northern Rhodesia was valued chiefly for the Copperbelt in the north bordered the Belgian Congo and as a result, there was only limited white settlement, with around 15,000 whites in 1939. Southern Rhodesia developed as an economy that was narrowly based on the production of a small number of primary products (notably, chrome and tobacco) and was vulnerable to economic cycles, with the depression of the 1930s having a devastating effect on the economy.

Nevertheless, in 1939 the white population of Southern Rhodesia was approximately 67,000 – 10,000 of whom would serve in the military in WW2. In Rhodesia, support for the Empire was strong – Rhodesian society was insular, colonial and highly patriotic. When the Russo-Finnish Winter War broke out, support for Finland was strong but it was felt that Rhodesia could do little or nothing to assist. The news that New Zealand, and then South Africa, followed quickly by Australia and Canada, were all sending volunteer units to fight in Finland stirred public opinion in Rhodesia.

It was generally felt that if the other British Dominions were sending volunteer units, then the Rhodesias’ too should play a part. With the small Rhodesian population however, there was considerable debate on just what part if any should and could be played. The Rhodesian economy was heavily agricultural and with a large black workforce, which made it easier to withdraw white European manpower for the military. Memories of WW1 were still vivid however, and the experience of the Great War had shown that entire battalions could be annihilated in single actions, which argued against the creation of a homogeneous Rhodesian volunteer unit for service in Finland as a military disaster would mean a national catastrophe for the small population. However, the pride and nascent nationalism of Rhodesia were at issue as well, and in the end this would overwhelm fears of a Rhodesian Passchendaele in the Russo-Finnish War.

The Southern Rhodesian Prime Minister, Sir Godfrey Huggins, chatting to Rhodesian troops preparing to board the train from Bulawayo to Durban, en-route to Finland and the Winter War.

Selection was straight-forward. The population of Rhodesia was small, the criteria were straight forward – young, single, in good health and familiar with firearms – the last applied to pretty much every Rhodesian. Within a fortnight of the decision having been made, the Volunteers had been selected and had assembled at Bulawayo. On Sunday, 14th January, 1940, a heavy troop-train drew out from the main line platform at Bulawayo. Most of the population of the town had come down to the station to wish luck to the soldiers – luck which would not be shared alike by all. The Prime Minister, Sir Godfrey Huggins, had just given the departing troops a message, “All I wish to say to you is this: we know that you will carry on the traditions that this young Colony established in the last war.” Then, as the train drew out, the troops shouted a cheerful chorus as they waved to the silent crowd of relatives and friends. It was easy for those who were en route to adventure to have faith and fire within them; it was more difficult for those who would stay behind and wait.

Daddy Went to Fight for the Green and White: An old Rhodesian song written about the small group of Rhodesian Volunteers who went to far-distant Finland

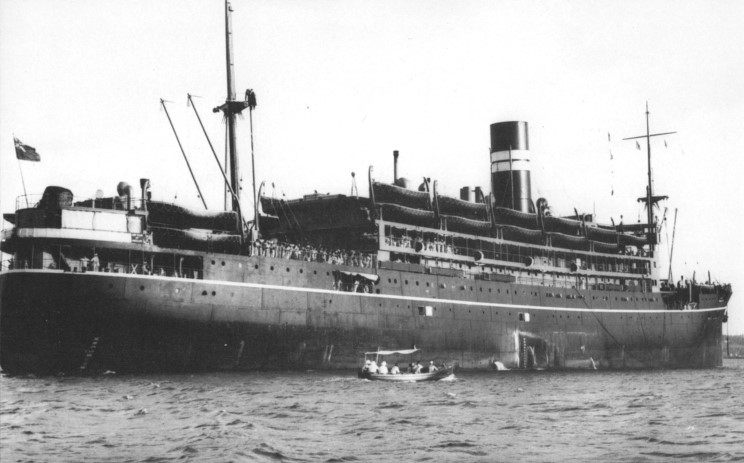

The Volunteer contingent, approximately seven hundred strong, destined for the war then being fought in the ice and snow of Finland, arrived at Durban docks two days later and there had a taste of the kindliness and hospitality of the Durban people, memories of which they were to carry with them in the lean days to come. There was a magnificent lunch in a shed on the quay, and the gift of a parcel containing cigarettes, socks, pyjamas for each soldier. Then the troops embarked on the troopship, the British India liner Karanja, and in the evening Durban gave them a rousing send-off.

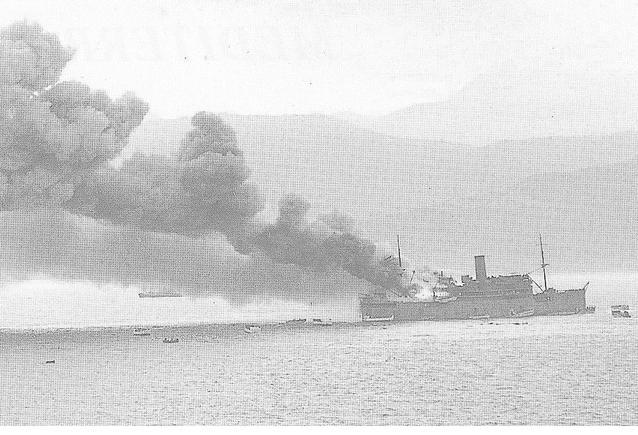

Built by Alexander Stephen in 1930 for the British India Line, KARANJA was powered by steam turbines, single reduction geared to twin screws, which gave her 16 knots on trials. As first commissioned, she had passenger accommodation for 60 first class, 180 second and 75 ‘intermediate’ in addition to which she had a certificate for 1,322 deck passengers on long voyages and no fewer than 2,208 on short voyages – all on a gross tonnage of 10,294! Routes covered by the British India Line were very numerous and formed a network covering the whole of the Indian Ocean which was the main sphere of operations. Some of the services extended to the U.K. via Suez and the Mediterranean, to Japan and New Zealand. Many British India Line ships would be used as troop transports in WW2 and some 50% of the fleet was sunk over the course of the war. Karanja was one of these, being sunk by Soviet air attack outside Petsamo after having disembarked the Rhodesian Volunteers.

SS Karanja was one of the casualties of war, being sunk in a surprise Soviet air attack as she steamed out of Petsamo after having disembarked the Rhodesian Volunteers.

The voyage was without incident, but hot and sultry through the tropics, especially for those who were accommodated on the troop-decks. The ship’s officers were so considerate and untiring in their efforts to assist the Rhodesians that it was resolved that their names be submitted for honorary membership of the Mess of the First Battalion, The Rhodesia Regiment. In late March 1940 the contingent arrived safely at Petsami and was met by several officers from the advance party together with their Finnish Liaison Officer. Within a few hours of landing, the battalion was in trucks and moving southwards to the Army Training Camp at Lapua, where they would be equipped and trained by the Maavoimat.

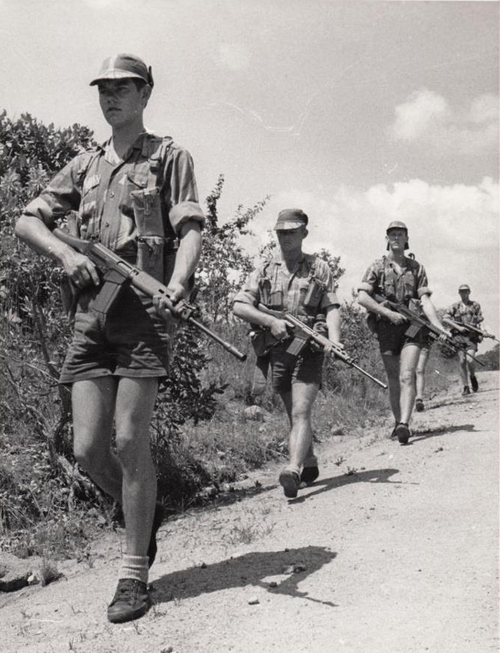

“They wear undersized shorts, like football trunks” the press announced in hushed tones…… Here, Rhodesian soldiers of the Selous Volunteer Battalion on patrol in Eastern Karelia, Summer 1940. The rifles are the Maavoimat-issued Lahti-Salaranta 7.62mm SLR’s that were, by mid-1940, in general use across all front-line infantry formations of the Maavoimat.

The arrival of the Rhodesian troops in Finland excited interest and curiosity. There was, of course, a certain amount of doubt as to where exactly Rhodesia was and what it was. The Helsingin Sanomat put everybody right. “Rhodesia is a small British Colony in Southern Africa,” it said, “distinct and separate from South Africa, it gave its full quota of men to the British armies in the Great War, and there is a fair proportion of veterans in this, the Rhodesian contingent to Finland.”

The contingent of Australian Volunteers had arrived at the same time as the Rhodesians, and it was inevitable that there should be comparisons. “The Rhodesians are older and more reserved than the Australians,” The Helsingin Sanomat decided. One startling feature worried the Newspaper Reporter, however. It was the sawn-off Rhodesian shorts that they wore indoors where it was warmer, the Folies Bergere-like brevity of which caused grave speculation. “They wear undersized shorts, like football trunks” the press announced in hushed tones……

Rhodesians of the Commonwealth Division in the Winter War – the Rhodesian Selous Volunteer Battalion

In late 1939, the Rhodesia and Nyasaland Defence Force, as it was then known, was very small – and fell under the overall aegis of the British South Africa Police (BSAP) who were trained as both policemen and soldiers until 1954. Between the World Wars, the Permanent Staff Corps of the small Rhodesian Army consisted of only 47 men. The majority of the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers dating from prior to WW1 were disbanded in 1920 for reasons of cost, the last companies being disbanded in 1926. The Defence Act of 1927 created a Permanent Force (the Rhodesian Staff Corps) and a Territorial Force as well as national compulsory military training. With the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers disbanded in 1927, the Rhodesia Regiment has been reformed in the same year as part of the nation’s Territorial Force. The 1st Battalion was formed in Salisbury with a detached “B” company in Umtali and the 2nd Battalion in Bulawayo with a detached “B” Company in Gwelo. The sole permament military unit in the Rhodesias was the Rhodesian African Rifles (made up of black rank-and-filers and warrant officers, led by white officers; abbreviated as “RAR”). From 1936 through to 1945, this small force was commanded by Brigadier John Sidney Morris.

Photo, Left: Brigadier John Sidney Morris (1890-1961) CBE; KPM; CPM; Brigadier – Commissioner 15 February 1933 to 24 April 1945. Born 1890 Didsbury, Lancashire and attended Grammar School in Manchester. He enlisted with the BSA Police in October 1909 and served mostly in the Mashonaland districts. Morris was commissioned in April 1914 and appears to have transferred to the CID in 1915. He served in Bulawayo and Salisbury, achieving the rank of Superintendent in 1926. In November 1929 he became an Assistant Commissioner with the rank of Major. Officers had both military and police ranks at this time. In the lead up to the Second World War, Morris was appointed Commandant of the Southern Rhodesian Forces. John Morris died in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, on 18 November 1961. Awarded CBE 1935; OStJ 1938; CPM 1944; KPM 1945.

It would be Brigadier Morris who would determine the size of the volunteer unit to be sent and who would appoint the CO from the very limited pool of Officers within the Rhodesian defence forces. And a very limited pool it was indeed.

Some 9,187 white Southern Rhodesians (15% of the white population of around 67,000, of whom 6,520 served outside the country) mustered into the British forces during the Second World War, serving in units such as the Long Range Desert Group, No. 237 Squadron RAF and the Special Air Service (SAS) with most scattered across various British units. Pro rata to population, this was the largest contribution of manpower by any territory in the British Empire, far outstripping that of Britain itself. As previously mentioned, outside of Rhodesia, the Rhodesian troops were split up and distributed amongst British and Commonwealth units to afford the infliction of massive casualties and the impact this would have on a small population. Rhodesians would however be disproportionately represented in a range of British Special Forces units (primarily the Long Range Desert Group and the Special Air Service) and Southern Rhodesian pilots would proportionally earn the highest number of decorations and ace appellations in the Empire (this later resulted in the Royal Family paying an unusual state visit to the colony at the end of the war to express their thanks for the efforts of the Rhodesian people).

Thus, the decision to send a single “all-Rhodesian” volunteer unit of some 800 men – more than 10% of the Rhodesian manpower available and eligible for overseas military service) was a significant step to be taken by this small country. That it was taken in full recognition of the risks this entailed, particularly as the war that they were going to was against a major military power, and after a full and frank debate of the possible ramifications for Rhodesia, must be a credit to the Rhodesians of that time. It was not a step taken lightly, and the solemn farewell for the volunteers at the Bulawayo Railway Station was evidence of that, if any more was needed. Despite the solemn mood of the farewell, the volunteers themselves were cheerful enough. Most of them were young and single, most were in their twenties, many were farmers, hunters and trackers, used to life on the veld, almost all were crack shots, fit and tanned from a largely outdoor and very physical lifestyle on the typical Rhodesian farm of that era.

The Rhodesian Defence Forces were small, all the Officers were either Territorial Officers of the Rhodesia Regiment or recently commissioned young Lieutenants given brevet appointments as Company CO’s and both they and the NCOs were mostly young men, their only military experience being the rather cursory training that had been offered by the Rhodesia Regiment in the years before the war, when budgetary constraints significantly restricted training opportunities. Many of the enlisted men and junior NCO’s had no training whatsoever. Nevertheless, despite the small Rhodesian population, selection had been rigorous (There had in fact been many more applications than there were places, with some South Africans making the journey to Rhodesia to apply after having missed out on joining the South African volunteers). All members of the Battalion had passed a stringent two week selection course that the Battalion CO had improvised – and memories of this one-off selection process would later be resurrected for use in the Rhodesian Army of the 1960’s and 1970’s.

Volunteers for the Battalion met in Salisbury where they were given a taste of the hardships they would have to endure to get into the ranks of those selected to go to Finland. Their first task was to reaching a temporary Camp in the country (which was a 15 mile run away from central Salisbury where they started) they saw only a few straw huts and the blackened embers of a dying fire. There was no food issued. The objective of the selection process at this point was to narrow the list of potential recruits by starving, exhausting and antagonizing them. This was successful, with 29% of the 1800 volunteers dropping out within the first two days. The selection course had a total duration of 12 days.

From dawn to 7 am recruits were put through a strength-sapping fitness program. After they had completed this, they trained in basic combat skills. They were also required to traverse a particularly nasty assault course daily. The course was designed to overcome their fear of heights. When darkness fell, they began night training. No food was issued over the first 5 days, after which the volunteers were fed only on rotten animals. At the end of the 11th day, they had to carry out an endurance march of 100 kilometres. Each volunteer was laden with 30 kilograms of rocks in his packs. These rocks were painted red, to ensure that they could not be discharged and replaced at the end. The final stage of this march was a speed march, and had to be completed in two-and-a-half hours. Those who survived were cleaned up, fed and placed on the train to the final assembly point at Bulawayo. It says a lot for the quality of the Rhodesian volunteers that 800 of the original 1800 applicants lasted through the selection course and were accepted into the ranks of the Battalion.

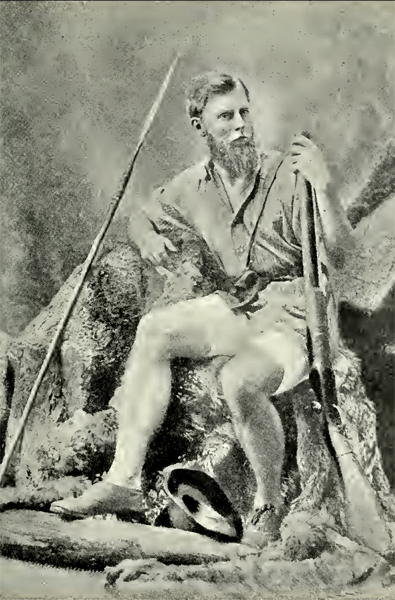

By acclamation amongst the officers and men of the Volunteers who had been selected, it was decided to name the Battalion the “Selous Battalion, Rhodesian Volunteers”, after the famous African hunter and explorer, Frederick Selous.

Frederick Courtney Selous, British explorer, officer, hunter, and conservationist, famous for his exploits in South-East Africa and after whom the Selous Battalion was named. His image remains a classic, romantic portrait of a proper Victorian period English gentleman of the colonies, one whose real life adventures and exploits of almost epic proportions generated successful Lost World and Steampunk genre fictional characters like Allan Quatermain (for whom he was , the inspiration behind Sir H. Rider Haggard’s creation of the character). He was to a large extent an embodiment of the popular “white hunter” concept of the times; yet he remained a modest and stoic pillar in personality all throughout his life. He arrived in Africa in 1872, at the age of 19, and from then until 1890, with a few brief intervals spent in England, he hunted and explored over the then little-known regions north of the Transvaal and south of the Congo Basin, shooting elephants, and collecting specimens of all kinds for museums and private collections.

His travels added greatly to the knowledge of the country now known as Zimbabwe. He made valuable ethnological investigations, and throughout his wanderings—often among people who had never previously seen a white man—he maintained cordial relations with the chiefs and tribes, winning their confidence and esteem, notably so in the case of Lobengula. In 1890, Selous acted as guide to the pioneer expedition to Mashonaland. Over 400 miles of road were constructed through a country of forest, mountain and swamp, and in two and a half months Selous took the column safely to its destination.

He returned to Africa to take part in the First Matabele War (1893), after which he returned to England, married, and then in 1896 settled on an estate in Matabeleland. He took a promient part in the fighting after the Second Matabele War broke out and published an account of the campaign entitled “Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia” (1896). It was during this time that he met and fought along side Robert baden-Powell, who was then a Major and newly appointed to the British Army headquarters staff in Matabeleland. In World War I, at the age of 64, Selous participated in the fighting in East Africa, rejoining the British Army.

He was promoted Captain in the uniquely composed 25th (Frontiersmen) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers on 23 August 1915. On 4 January 1917, Selous was fighting a bush-war on the banks of the Rufiji River against German colonial Schutztruppen, outnumbered five-to-one. That morning, in combat, during a minor engagement, while creeping forward, he raised his head and binoculars to locate the enemy, and was shot in the head by a German sniper. He was killed instantly. He was widely remembered in real tales of war, exploration and big game hunting as a balanced blend between gentleman officer and epic wild man. Post WW2, another elite Rhodesian military unit, the Selous Scouts, was named in his honour.

The Rhodesian Government on the advice of Brigadier Morris appointed Major (T/Lieutenant-Colonel) Graf (Count) Manfred Maria Edmund Ralph Beckett Czernin von und zu Chudenitz to command the Battalion. (referred to hereafter as Lt-Col. Czernin).

Company Officers who passed Selection and were appointed were:

Captain (T/Major) Paul Newton Brietsche, Commanding Officer, Headquarters Company;

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Sam Putterill Commanding Officer, A Company;

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Alan Gardiner Redfern, Commanding Officer, B Company;

Lieutenant (T/Captain) John Richard Olivey, Commanding Officer, C Company;

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Edgar Walter Dudley Coventry, Commanding Officer, D Company;

Lieutenant (T/Captain) John (“Jock”) Anderson, Commanding Officer, Heavy Weapons Company:

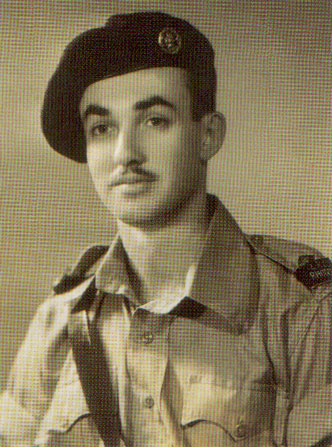

C/O Selous Battalion: Major (T/Lieutenant-Colonel) Graf (Count) Manfred Maria Edmund Ralph Beckett Czernin von und zu Chudenitz

Major (T/Lieutenant-Colonel) Graf (Count) Manfred Maria Edmund Ralph Beckett Czernin von und zu Chudenitz, Commanding Officer, the Rhodesian Selous Volunteers

Major (T/Lieutenant-Colonel) Graf (Count) Manfred Maria Edmund Ralph Beckett Czernin von und zu Chudenitz, Commanding Officer, the Rhodesian Selous Volunteers: Czernin was born on 18 January 1918 in Berlin, the fourth son of Count Otto von Czernin, an Austrian diplomat, and his English wife, Lucy, daughter of Ernest Beckett, 2nd Baron Grimthorpe. Several years after he was born his parents were divorced and young Manfred moved to Italy with his mother, but was educated in the United Kingdom at Oundle School. In September 1931 he moved to Rhodesia to work on a tobacco plantation.

Czernin returned to the United Kingdom in April 1935 to take up appointment as an Acting Pilot Officer on a short service commission. Qualifying as a pilot, he was posted to No. 57 Squadron RAF at RAF Upper Heyford, and enjoyed several more squadron postings until placed on the Class A Reserve. Returning to Southern Rhodesia in September 1937, Czernin joined the Rhodesian Air Force Reserves but transferred to the Rhodesia Regiment some months later, with the rank of Captain.

A keen young Officer, and recognised as highly competent, he was promoted to Major in late 1937 and would complete General Staff training at Quetta in 1938 – one of the very few Rhodesian Officers to have done so. He married Maud Sarah Hamilton on 4 November 1939 – and then immediately volunteered for Finland when it was announced that Rhodesia would be sending a Battalion of volunteers and was selected as the CO, with the Acting Rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. A fluent speaker of both German and Italian, he commanded the Battalion throughout the Winter War with distinction.

After the Winter War ended, he would return to the UK and transfer into the RAF where he dropped ranks to fly fighters. In late 1941, after 13 victories and 5 shared victories, he was awarded the DFC and promoted to Squadron Leader. In 1942 he was Staff Officer for 224 Group and in 1943 he was transferred to the Air Ministry. In September 1943 he transferred to SOE as “Major Beckett” and was dropped into Italy where he won the Military Cross (1944) and the Distinguished Service Order (1945). He left the RAF in October 1945, became Sales Manager for Fiat in the UK and died suddenly in October 1962 in London.

Captain (T/Major) Paul Newton Brietsche, Commanding Officer, Headquarters Company

Captain (T/Major) Paul Newton Brietsche, Commanding Officer, Headquarters Company. Born 13 July 1910 in the UK and having immigrated to Rhodesia in 1935, Brietsche was a farmer/gold miner in civilian life and an Officer in the Rhodesia Regiment (the Territorial Force of the Rhodesia and Nyasaland Army). A Captain at the time of volunteering, he was given a brevet promotion to Major and appointed to the command of Headquarters Company.

After the Winter War, he would return to the Middle East, join the LRDG (Long Range Desert Group) and command R Patrol. He would later transfer to the SOE and fight behind enemy lines in Italy in 1944, where he was awarded the Military Cross.

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Sam Putterill, Commanding Officer, A Company

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Sam Putterill, Commanding Officer, A Company, Rhodesian Volunteer Battalion: Rodney Ray Jensen Putterill (always known as “Sam”) was born in Harrismith, South Africa in January 1917. His family moved to Southern Rhodesia where Sam was educated. After university, he worked for an oil company in Northern Rhodesia but was persuaded to join the Rhodesian Army. Commissioned in 1939, he volunteered for service in Finland and fought with the Selous Battalion in the Winter War. Between 1939-1945 he had a brilliant military career, fighting the Russians in Finland, the Germans in North Africa, the Italians and Germans in Italy, then communists in Greece.

As with so many other Rhodesians and South Africans who studied British military tactics against communists in Malaya at the end of the Second World War, Putterill believed he and his men could “hold” the forces of Black Nationalism in Central Africa in the 1960s’. As time showed, they weren’t ruthless enough and couldn’t. Appointed General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the Rhodesian Army in 1964, he was GOC when Ian Smith declared UDI in November 1965 (succeeding Major-General Jock Anderson, whom Ian Smith had forced into retirement in 1964).

When he warned Prime Minister Smith that he could never go along with Smith’s plan to turn Rhodesia into a republic in 1970, he was forced into early retirement in 1968. During the campaign for a Republic in 1969, Sam Putterill came out of retirement and addressed white audiences throughout the country – “With his ringing voice and fierce, far-seeing eyes he inspired great confidence in his deep knowledge of the country’s politics and contemporary history.”

Putterill spent the rest of his life lambasting Ian Smith from the country’s political sidelines, becoming in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s a leading light in the small (but annoying to Smith), Centre Party, led by a white commercial farmer called Pat Bashford and supported by the ex-colony’s handful of European liberals. He and the Centre Party became irrelevant as Rhodesia turned into Zimbabwe in 1980. Sam Putterill and Ian Smith died within a few days of one another in October 2007 – enemies in life but men who from different positions watched with horror at the way Robert Mugabe went on to turn what was once called the Jewel of Africa into yet another of that continent’s many shameful basket cases.

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Alan Gardiner Redfern, Commanding Officer, B Company

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Alan Gardiner Redfern, Commanding Officer, B Company, Rhodesian Volunteer Battalion: Redfern was born in 1906, the son of Arthur William and Margaret A. Redfern,Salisbury,Southern Rhodesia. Married to Agnes Opal Redfern of Salisbury, he was an officer in the Rhodesian African Rifles when WW2 broke out. After fighting in the Winter War, he would join the LRDG (Long Range Desert Patrol) in the Middle East where he could command the LRDG’s B Squadron. Returning to Rhodesia, he would run commando training courses in Gwelo, Southern Rhodesia (for which he was awarded the MBE). He returned to the fighting in the Mediterranean and was KIA on Leros on 12th November 1943. He s buried in the Leros War Cemetery,Greece.

Lieutenant (T/Captain) John Richard Olivey, Commanding Officer, C Company

Lieutenant (T/Captain) John Richard Olivey, Commanding Officer, C Company, Rhodesian Volunteer Battalion: from Southern Rhodesia, Olivey would return from the Winter War to the Middle East, where he would join the LRDG in January 1941 and go on to fight in North Africa. He was taken POW on Leros on 18 November 1943 but escaped.

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Stanley Norman Eastwood, Commanding Officer, C Company

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Stanley Norman Eastwood, Commanding Officer, C Company, Rhodesian Volunteer Battalion: from Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, Eastwood would go on to join the LRDDG in the Middle East after the Winter War. He would be awarded the Military Cross and a Mention in Despatches for actions in Albania in 1944.

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Edgar Walter Dudley Coventry, Commanding Officer, D Company

Lieutenant (T/Captain) Edgar Walter Dudley Coventry, Commanding Officer, D Company, Rhodesian Volunteer Battalion: born 26 March 1915 in India and educated at Bryanston, Coventry was commissioned in 1938 and volunteered for Finland. After the Winter War he would join 5 Commando and Special Raiding Forces Middle East, then serve in 45 R.M. Commando 1944-45 and the East Lancashire Regiment 1946 before transferring to the Parachute Regiment.

He would serve in the Independent Parachute Squadron and (the Rhodesian) C Squadron 22 SAS (Malaya) where he was awarded a Mention in Despatches in 1956. He served in the Rhodesian Light Infantry 1960 and was CO, C Squadron Rhodesian SAS in 1963, joined the Rhodesian Central Intelligence Organisation in 1970, was WIA several times in Rhodesia and as a Lt Col was CO of the Zimbabwe SAS. He died on 5 September 1993 in Harare.

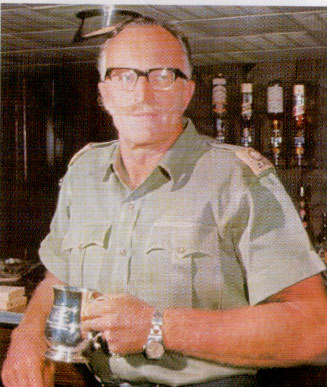

Lieutenant (T/Captain) John (“Jock”) Anderson, Commanding Officer, Heavy Weapons Company

John (“Jock”) Anderson (photo taken when GOC, Rhodesian Army in the early 1960’s). Lieutenant (T/Captain) John (“Jock”) Anderson, Commanding Officer, Heavy Weapons Company: A young Officer in the Rhodesian African Rifles, Anderson would remain in the Army and go on to command the 1st Battalion, Rhodesian African Rifles in Malaya from 1956 to 1958. They were stationed for a brief period at Kluang and then on the Tanemera Rubber estates and had the highest kill rate of any regiment during that time, winning a number of MM’s (the Regiment was disbanded in 1980 when Zimbabwe was formed).

Lt-Col. Anderson also commanded 48 Gurkha Infantry Brigade for a period of 6 months during the Malayan Emergency. He went on to be promoted to Major-General and became General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the Army of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. At the breakup of the Federation, he commanded the Southern Rhodesian Army and controversially, was sacked by Ian Smith due to his refusal to condone UDI. He went on to work for Tiny Rowland of Rhodesia and died in the UK in 1992. Two of his sons went on to serve with 6th QEO Gurkha Rifles.

The Selous Battalion in action

One of the Battalions more notable young junior Officers was B Company 2IC, 2nd Lieutenant Ken Harvey. The son of a shopkeeper, Kenneth Gordon Harvey was born on December 7 1920 in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia, and educated at Milton Junior and Senior schools, where he was acknowledged to be bright but not academic. On leaving school, he spent nine months with the Rhodesian Railways, then enlisted and was commissioned into the Rhodesia Regiment. Volunteering for Finland, he was appointed 2IC in B Company (with a shortage of qualified young Officers, the Platoons within each Infantry Company were generally commanded by a senior NCO rather than an Officer).

Perhaps the most audacious mission in which the young Lt Harvey took part was the attack upon the a Red Army Corps Headquarters during the defence of the Syvari in August 1940. The primary objective of this operation was to kill or incapacitate as many Red Army staff officers as possible (including the Corps commander) & by so doing hopefully throw the whole command & control structure in that region into disarray. The HQ had been identified as being sited in two houses in a village &, as to be expected, was heavily guarded. The decision was taken to deploy some of the Rhodesians to assist the men of Osasto Nyrkki, who by August 1940 had taken numerous casualties and were significantly under strength. The Rhodesians were to move in as one of the main assault groups. The combined raiding force made a long approach on foot through thickly forested terrain to the target and, during the hours of darkness, positioned themselves for the attack.

The signal to launch the assault was given by a radio signal and the night was soon filled with the sounds of gunfire as the Rhodesians went into the attack. Lt Harvey led one team of soldiers towards the house which he had been tasked to clear, personally killing two Russian sentries on the approach. The front door of the target building was removed by a Rumpali round after which Lt Harvey’s team entered to get to grips with those inside. Several Russians were killed in the ensuing contacts on the ground floor yet when Lt Harvey attempted to lead the assault on the first floor his team came up against desperate resistance from a scratch force of Red Army officers. A particularly vicious close quarters firefight ensued. Leading from the front Lt Harvey attempted to fight his way up the staircase several times only to be beaten back on each occasion by heavy automatic fire and grenades. Knowing that his twenty minute time frame was almost up, Lt Harvey ordered his men to set fire to the ground floor before withdrawing under automatic fire from both the house and several positions in the village back to his start line.

By this time the building was fully ablaze and those inside who realised the need to escape death by fire were cut down by the Rhodesians (who had been keeping a steady fire upon the enemy held portions of the house) as they jumped from the upper storey windows. By now the Red Army response was in full swing and the order was given to withdraw. Under very heavy small arms, machine gun and AA cannon fire the raiding party disengaged taking their two wounded with them. Over the next 36 hours or so they were chased by a vengeful enemy, including NKVD units, who were intent on stopping them. However the Rhodesians and their Osasto Nyrkki guides made good their escape into the forest. It was later learned that the Russians had lost several visiting Red Army and Communist Party VIPs in the attack including three Generals and the Corps Chief of Staff.

After service in Finland, Harvey would serve in the Middle East and join the SAS, where he was awarded the DSO and would see active service behind enemy lines in Italy. He was troubled by the suffering of the SAS wounded who could not be given proper treatment and were often transported on ladders. As a result he raided a German hospital, where he commandeered a Mercedes ambulance and an Opel staff car complete with its driver. He subsequently sold the car in Florence on the black market, and spent the proceeds on a three-day party after his return to England. After the war ended, Harvey was demobilised and returned to Africa, going up to Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg, to read Architecture. While in Africa and Italy he had developed a great affection for the bagpipes and Highland dances; while an undergraduate he enrolled in the Transvaal Scottish. Harvey returned to Bulawayo in 1951 as a partner in a firm of architects, but never completely settled into civilian life. He subsequently joined the 2nd Battalion, Royal Rhodesia Regiment, and took command in 1962 with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

Harvey saw active service in Nyasaland (now Malawi) in 1959, when he helped to suppress riots which had broken out in protest at the colony being linked to Northern and Southern Rhodesia to form the Central African Federation. He commanded Operation Wetdawn, a sweep of villages known to harbour African nationalists. This nipped a possible rebellion in the bud, and Harvey was awarded an MBE (military) for “loyal and meritorious service”. Subsequently he served as honorary colonel of the Rhodesian SAS. A modest, friendly man, Harvey continued working as an architect after Rhodesia gained its independence as Zimbabwe in 1980. He established a large practice and designed many of the office buildings in Harare and Bulawayo. Harvey was deputy chairman of the Central Africa Power Corporation for many years. As chairman of the Zimbabwe Legion, he worked hard to help ex-servicemen, particularly those whose savings were destroyed by hyperinflation. In his spare time he was a keen philatelist. Despite the onset of cancer, he was most reluctant to leave the country, but was eventually persuaded to move to a retirement home in Cape Town. There he struck up a friendship with another resident, Ian Smith, the former Rhodesian prime minister. Ken Harvey died on December 3. He married Luna Klopper in 1951 (she predeceased him). He was survived by their three daughters.

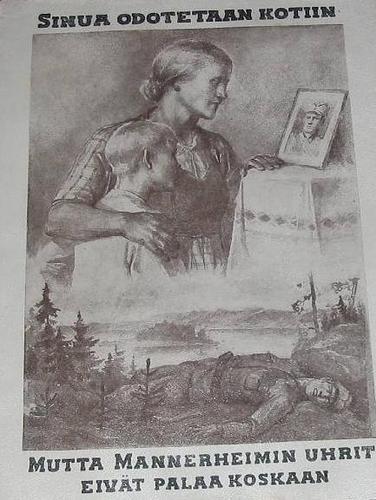

Illustration, Left: “There were no Survivors: The Rhodesian Syväri Patrol, August 1940” – A Soviet Propaganda leaflet dropped over Finnish lines shortly after the annihilaton of the Syväri Patrol – the upper text says “You are expected home”, the lower says “But Mannerheim’s victims never return”. On the reverse, a description of the fate of the Syväri Patrol. Rhodesians collected the leaflets as souvenirs, some can still be found in Zimbabwe even today….

Another notable “behind the lines” action involving the Rhodesian Battalion was the ill-fated Syväri Patrol, a Platoon of 34 Rhodesian soldiers led by young 2nd Lieutenant Allan Wilson. The Patrol had been sent deep behind the Syväri to scout ahead of the main assault group of the Commonwealth Division prepatory to a major crossing of the Syväri in the last weeks of the Winter War. The patrol was dropped deep behind Red Army lines on the 3rd of August 1940 but had the ill-fortune to be spotted by a Red Army patrol almost immediately on disembarking from the Ilmavoimat float-planes that had landed them on a small lake. Aware within hours that they were being tracked, Wilson’s Patrol doubled back and, unable to be extracted by aircraft due to foul weather and low clouds, made for the Syväri.

However, with heavy rainfall, they were trapped by flooded rivers and surrounded in the night by 3,000 men of the Red Army who attacked on the morning of the 4th of August. The Patrol, out of range of Finnish artillery and unable to receive close air support due to the weather, made a dramatic last stand against insurmountable odds, fighting to the last round and killing thirty times their number before being annihilated shortly after sending a final radio message. Their fight achieved a prominent place in Finnish and Rhodesian public imagination and, subsequently, in Rhodesian national history. A historical war film depicting the episode, “Syväri Partio”, was produced and released in 1970.

The Syväri Patrol: an old Rhodesian song recording Wilson’s Last Stand in the Winter War

His troopers, they were loyal, his troopers, they were young

They’d follow Allan Wilson to the setting of the sun

They were hands from many lands, and many a distant shore

They would follow Wilson—a soldier to the core

Chorus:

Across the wild Syväri, behind the Russkie side

Across the wild Syväri, where Allan Wilson died

The Bolsheviki army was running to the south

And the Marski he would follow, for all that he was worth

But across the wild Syväri, Syväri River wide

Were Wilson and his men to scout, over the other side

Chorus (Repeat)

Through green Karelian Forest the Russkie soldiers fled

The Finnish tracker Lindorf said ‘They can’t be far ahead’

But Wilson and his troopers were surrounded in the night

Said Wilson to the volunteers: ‘We will stand and fight’

Chorus

With machineguns in a circle, they sang “God Save the Queen”

And thirty-four young troopers would never more be seen

They killed ten times their number; they’re on the honour roll

So take your hat off slowly to the Syväri Patrol

Chorusx2

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

5 Responses to Selous Battalion – Rhodesians of the Commonwealth Division in the Winter War