The prehistory of South Karelia

Twelve thousand years ago, Finland (the area between Norway/Sweden and the White Sea / Lake Onega) was almost totally buried under a continental ice sheet, just as Greenland is today. Gradually, the ice sheet melted, and its southern margin retreated farther and farther north and prehistoric South Karelia emerged from under the ice and the sea. As the ice load grew thinner and vanished, the earth’s crust began to rise – a process that has continued to this day, most markedly along the Gulf of Bothnia.

During that process, the Finnish peninsula slowly rose out of the sea, first forming solitary islands, then chains of islands, and, finally, a clearly defined extension of the continent. The retreating glacier striated the bedrock, leaving behind it vivid evidence of the ancient geologic process. During the melting stage, clay accumulated in annual layers, and pollen grains were preserved in peat, thus bearing further witness to the vicissitudes of Nature. Through the study of such phenomena, geologists have been able to deduce the origins of Finland. During extremely cold periods between 9 000 and 8 000 B.C., the continental ice sheet halted in its retreat three times and remained stationary for centuries. This led to the formation of two chains of eskers out of gravel and sand that were transported by streams of melting ice. These two separate ridges, known as the Salpausselklä ranges, run east and west across the entire breadth of Finland.

During the final stages of the Ice Age, the body of water that eventually evolved into the Baltic Sea was a huge and labyrinthine fresh water lake (the Ancylus Lake). As the land mass that was to become the Finnish peninsula emerged from this vast stretch of water, smaller lakes were formed within the rising land, becoming the tens of thousands of lakes of present-day Finland. However, the ground did not rise at an even rate everywhere, and, at times, the level of the sea rose, forcing rivers into new discharge channels and submerging extensive areas of land again.

While the continental ice sheet and great bodies of water still covered most of Finland, a tundra, overgrown with dwarf birch, bordered the glacial margin, both in the north and in the south. There, wild reindeer, Arctic fur-bearing animals, and – in the coastal waters – fish, waterfowl and seals, offered primitive hunters and fishermen a chance to eke out a livelihood. From those coastal regions of the Arctic Ocean, north of the present national boundary of Finland, have come the most ancient relics of human culture ever discovered by Finnish archaeologists. These date back to approximately 8 000 B.C.

Mesolithic Stone Age (8300 – 5100 BC)

Antrea Net fragments from Karelia, 8 000 BC

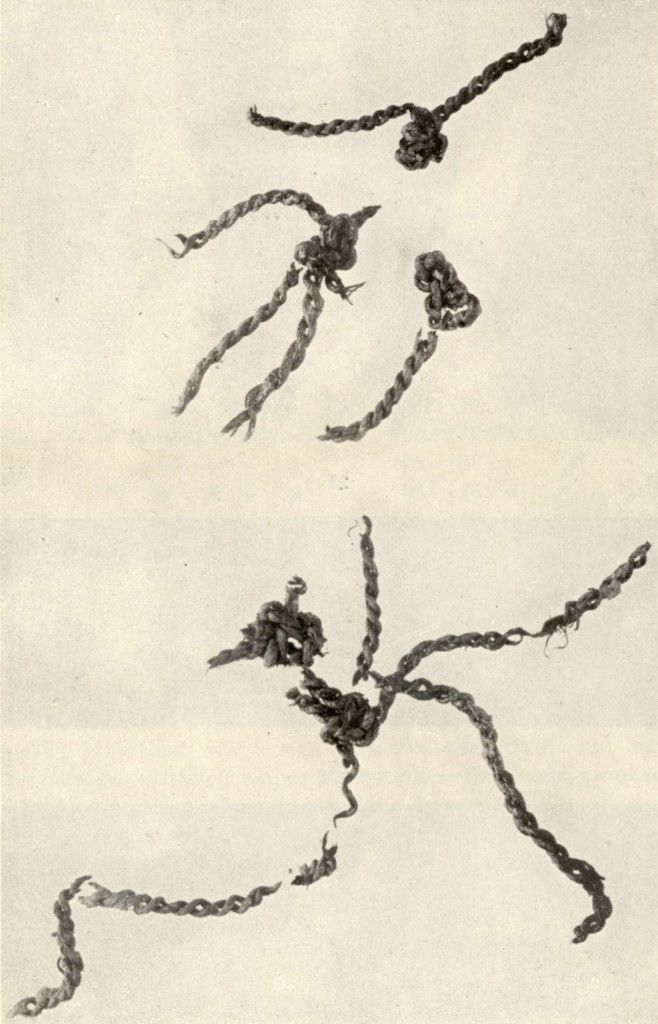

Recent archeological discoveries are shining a new light on the prehistoric inhabitatants of Finland. The world’s oldest fishing net is carbon dated at 10 000 years old. It was found in autumn 1913 in Korpilahti swamp at Antrea in Karelia (after WW2 and the seizure of Finnish territory by the USSR, Kamennogorsk, Russia) by a farmer named Antti Virolainen (while he was digging ditches to drain a swamp meadow). The site was then excavated by the Finnish archaeologist Sakari Pälsi. The net had sunk to the bottom clay of the Ancylus Lake , most likely in an accident involving the fisherman’s boat capsizing and the loss of all his equipment. Along with the net, various tools were found, including hunting weapons, fist-sized rock weights, floats made from Scots Pine bark and other tools made out of bones.

This net measured 27-30 metres x 1.3-1.5 metres, with a 6 cm mesh (obviously looking for large fish….). The find included 18 bark floats with holes which were attached to the top of the net, while 31 stone weights were retrieved (the stones weighed 450 550 g. each). Strips of birch bark recovered with the find were probably used to attach the floats and the weights. The net itself was made of willow bast (the inner bark fibre of willow) and two of its knots were so well preserved that they could be reconstructed. Sakari Pälsi, the archaeologist who excavated the find, identified the knot as belonging to a type with existing ethnographic parallels known only from Estonia and the eastern regions of the Finno-Ugrian people.

The net is estimated to have weighed about 30 kilograms when wet. The find also included a bone point with small quartz blades on one side, an axe made from an antler, and various stone artefacts, pieces of quartz and pieces of raw material. A perforated bone object may have been a flute. The Antrea Net is on display in the National Museum of Finland.

The Antrea net is usually considered the oldest Stone Age find in Karelia and, in fact, the whole of Finland. However, discoveries made since 1999 have revealed a number of even older dwelling sites in Imatra and Joutseno, on the Finnish side of the Russian border. The finds in Saarenoja in Joutseno are particularly significant, including not only quartz of domestic origin but splinters of flint, rare for stone age Finland, and a bone arrow with a cone-shaped head, indicating that the dwelling sites in question were inhabited by new settlers from the south or south-east. Equally ancient settlements have been discovered at various places along the Salpausselkä Ridge. In South Karelia, another find dating back to the same period is located in Luumäki (Ontela and Mustaniemi). The archaeological evidence from these sites also shows that among others, large cloven-hoofed animals such as the elk and deer were hunted by stone-age people.

For further prehistoric remains in South Karelia, see the Stone Age site of Rovastinoja at Savitaipale.

Kunda Culture (6000 – 5000 BC)

These most ancient human settlements of the Finnish regions were established by Baltic-Finns belonging to the Early Mesolithic Kunda culture (which emerged about 8700 BC), the roots of which are in the even earlier Swiderian culture. Finland received her first permanent settlers from the Kunda culture people’s territory in the south (Estonia) and east (Karelia) about 8500 BC. When these possibly Proto-Uralic-speaking groups arrived in northern Finland around 8000 BC, they met coastal groups, who had arrived in northern Fennoscandia as early as 9000 BC from then ice-free region between the British Isles and Denmark by following the ice-free coast of Norway. At that time, the inland regions of central and northern Scandinavia were still covered by ice. The coastal people may have become Uralic-speaking Saami as a result of cultural contacts with Proto-Uralic-speaking populations inhabiting inland regions of northern Fennoscandia. This language shift would explain why the Saami are genetically so distinct from Scandinavians and Baltic-Finns, but speak languages that are related to the Baltic-Finnish languages (a similar language change apparently occurred in Western Siberia where the Paleo-Asiatic inhabitants were linguistically assimilated by the Uralic-speakers, giving origins to the Samoyeds). A Kunda culture site within Finland has been identified at Ristola.

Comb Ware Culture (5100 – 3500 BC)

Combware Pottery – from the National Museum of Finland

Numerous settlements dating from the Comb Ware period – and especially from the so-called Typical Comb Ware period (4000 – 3500 BC) – have been discovered along the shores of Lake Saimaa. It seems that the epicentre of this phase of development was around Lake Saimaa; indeed, the decorative pattern typical of the age may even have originated here. Abundant use of flint and amber from abroad indicates that the people of the Typical Comb Ware period maintained active links with the outside world. In addition to flint flakes and arrowheads, the statuette of a bear, found in Syrjälä in Taipalsaari, is a good example of this ‘foreign trade’.

The Vaateranta settlement in Taipalsaari offers a rich insight into the lifestyle of people inhabiting the shores of Lake Saimaa, just before the River Vuoksi broke through the Salpausselkä Ridge at Vuoksenniska. The very same place is an excellent beach, even today. This location is significant due to the stone-age burial ground found there. Red ochre was sprinkled over the deceased, whose bodies were buried without cremation, which makes it easier to find the graves and associated remains today.

The 30 known rock paintings of the region probably date from the same period. Together with the paintings discovered in Southern Savo and Kymenlaakso (the valley of the River Kymi) they represent the largest concentration of rock art in Finland. Made with red ochre, these works are painted onto rock faces rising vertically from the water. The most usual themes are humans and cloven-hoofed animals. The region’s most famous painting, found in Kolmiköytisenvuori in Ruokolahti, depicts shamans and snake patterns.

Stone-Bronze Age (3500 BC – 250 AD)

Burial cairn, Kuurnankangas, Kälviä.

Late Stone Age culture continued almost unchanged into the Bronze Age, since little copper and tin was brought into this area. However, a small arrowhead made of metal and a copper bead have been discovered in Utula in Ruokolahti and Hiekkaniemi in Puumala. As early as the end of the Stone Age (1900 BC), it seems that people began to diversify from hunting and fishing into crop cultivation and animal husbandry. These new livelihoods apparently led to the disintegration of the settlement as such: the rich combware-culture lakeshore dwelling sites were abandoned and do not seem to have been replaced with anything similar, although the population evidently did not disappear.

Combed Ware pottery gradually changes to asbestos ceramics, which probably reflects the merging of the population groups which produced Combed Ware and asbestos ceramics. For instance, in the South Karelia region we know of the Kierikki (3600-3100 B.C.), Pöljä and Jysmä (3100-1900 B.C.) ceramics groups. Because of the paucity of artefacts found, we currently know little about the final period of the Stone Age in South Karelia. Use of asbestos becomes characteristic of the ceramics traditions of the age. The idea that clay vessels could be strengthened with asbestos fibres seems to have evolved quite early amongst people living on the northern shores of Lake Saimaa. Early Asbestos Ware has been named after Kaunissaari in Parikkala. Following the Comb Ware Culture, asbestos ware came to dominate the next phase in South Karelia. Commonly known asbestos ware types are those from Pöljä, Kierikki, Luukonsaari and Sirnihta. Textile ware, patterned with textiles, was made simultaneously.

In the Bronze Age, people were often buried in round mounds made of stone. Something indicative of this exists in South Karelia, too, as some shallow burial mounds of stone (Lapland cairns) have been found here. The carefully assembled cairns are in burn-beaten areas, almost without exception of late origin (1700–1800 BC).

The Iron Age (250 – 1320 AD)

The Iron Age marks the beginning of the farming economy. Distinct signs of crop cultivation dating from 500 BC and 750 AD have been discovered in Savitaipale and Luumäki, respectively. Kauskila in Lappeenranta was apparently cultivated terrain throughout the Iron Age. The extensive, ground-level burial ground in Kauskila, dating from the 13th to the 17th century, mainly contains Christian graves. The remains of a church or chapel have been discovered in the middle of this site.

For some reason, there are no pre-Viking Era (800-1050 AD.) finds in the Kauskila area at all. In fact, these are rare in the entire region. In recent years, abundant late Iron Age findings have been discovered in Ruokolahti (Kyläjärvi) and Rautjärvi (Purnujärvi). Apparently, the Vuoksi River valley and the province in general have been a source of goods and influences, communicated between the Lake Ladoga and Finland’s inland lake regions.

Defence based on ancient castles was characteristic of the Stone Age Culture. The ancient castles of Kuivaketvele in Taipalsaari and Turasalo are impressive sights. Set high up on steep rock outcrops, the ancient hill forts were places of shelter and defence where people of the Iron Age took refuge when threatened. On the least steep side of the rock, there are one or more stone bulwarks which were probably once the foundations for wood fortifications. Building and maintaining the castles required extensive organisation and cooperation. Construction of the ancient castles was begun at the end of the Iron Age. About 100 of them are known in Finland. They were in use generally from 800 to 1300 A.D.

In addition to Taipalsaari’s Kuivaketvele hill fort, two other hill forts have been identified in Taipalsaari: the Kannus and the Turasalo hill forts. Viking-era burial grounds in Vammonniemi and Mammonniemi indicate that people lived in Taipalsaari during the Iron Age. At these burial grounds, ashes of the dead and burial offerings were hidden in hollows in the rock or in cairns. The top of the hill fort offers a magnificent view of Lake Saimaa. Steps have been built into the steepest parts of the hill fort.

The spread of the population in the Iron Age can be followed by observing the burial grounds, for they are often easier to notice than the dwelling sites, which in many places lie beneath current housing. A cup stone, that is, a stone or rock with cup-like indentations ground into it, may also signal a burial ground or dwelling site nearby. Sacrificial offerings such as grain and milk were brought to these cup stones, according to historical data. These cup-stones can be found here and there throughout the South Karelia region.

The Viking Period

The Invitation of the Varangians by Viktor Vasnetsov: Rurik and his brothers Sineus and Truvor arrive in Staraya Ladoga

As the Vikings opened a road to the east in the 800s, the changes were reflected in South Karelia, as well. People traveled through the wilderness trading furs and other items. Settlers and new influences made their way into the region via the waterways, trading settlements and farms were built in good locations. Defensive fortifications were erected against unrest.

The pulse of the times are particularly visible in Taipalsaari, where a village-like settlement grew. Burial grounds at Vammonniemi and Mammonniemi and the hill forts at Kuivaketvele, Vitsai and Turasalo, perhaps built as refuges, tell of the existence of a society that already practiced both agriculture and animal husbandry. The cemetery with burial cairns in Hirnilä in Rautjärvi was most likely the burial site for a wilderness station or pioneer farm. Tools and weapons found there tell of slash-and-burn practices of clearing woodland for cultivation, and also of the dangers lurking in the wilds.

Contact among nations is evident: among the beautiful artefacts found in the prehistoric settlement at Karoniemi in Ruokolahti are luxury items from Viking times, glass beads which were made in the Mediterranean region. Contact existed between the southeastern shore of Lake Ladoga and Häme and western Finland, and some of the travel routes probably went through prehistoric South Karelia.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland