I – Suojeluskuntas – an Introduction

Earlier in this thread, we looked at the origins of the Suojeluskunta in the Finnish Civil War and the preceding unrest. In this post, we will go on to look at the Suojeluskunta and the associated Lotta Svard organisation for women in the 1920’s as a prelude to examining their changing roles and responsibilities through the 1930’s. At this point, I should state that the historical content in this Post is very largely based on the excellent English-language writeup on the history of the Suojeluskunta and Lotta Svard organizations written by Jarkko Vihavainen, to whom all credit goes for a very thorough presentation for organizations on which there isn’t that much available in English.

As mentioned in the earlier posts on the Suojeluskunta (Civil Guard), this was an organisation of a type that is a little difficult for many in modern Western societies to grasp as the “Civil Guard” type organisation is somewhat alien a concept to our modern military organizations. That said, groups such as the Suojeluskunta (Civil Guard) are not all that uncommon in many areas of Europe and this types of volunteer military organization was widespread in the countries that liberated themselves during the the dismantlement of Tsarist Imperial Russian and indeed the Suojeluskunta and Lotta Svard organizations served as models for similar organizations that were setup in neighbouring countries in the Baltic and Scandanavia between the World Wars (and afterwards in some cases).

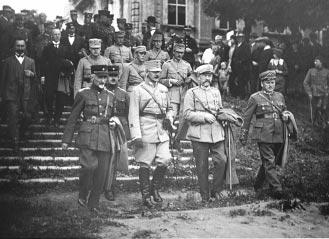

Representatives of the Suojeluskunta visiting the Aizsargi organisation in Jelgava 1924. (Photo from Latvian War Museum)

For example, the Latvian Aizsargu Organizācija (“Guards Organization”) was a paramilitary militia that was created on March 30, 1919 by the Latvian provisional government as a self-defence force during the period of unrest and civil war that followed the Bolshevik Revolution. In 1921, the Aizsargi was reorganized to follow the example of the Finnish Suojeluskunta, with its own newspaper (Aizsargs – “Defender”/”Guard”), a women’s wing (the (“Aizsardzes”) and a youth wing (the “Jaunsargi”). In January 1940, there were 31,766 aizsargi, 14,810 aizsardzes and 14,000 jaunsargu. The organisation was disbanded in June 1940 as a result of the Soviet occupation of Latvia but a similar organisation was reconstituted in 1991 (known as the Zemessardze, or National Home Guard) when Latvia once again became a free nation.

In Estonia, a similar organisation existed from 1918 to 1940. This was named the Kaitseliit (National Defense Force), and again was in many regards very similar to the Finnish Civil Guard organization and system, having originally been formed as protection against the public disorder accompanying the Russian Revolution and then participating in the War of Independence. The attempted Communist coup in Estonia on December 1 1925 dispelled any doubts about the necessity for the Defence League Organisation and led to its strengthening. The Kaitseliit had its own newspaper, “Kaitse Kodu!” (“Defend Your Home!”), in 1927 the Women’s Home Defence (Naiskodukaitse) auxilary was founded, in 1928 the boy scout organisation Young Eagles (Noored Kotkad) was invited to join the Defence League and finally in 1932, the Defence League’s Girls’ Corps (the Kodutütred) was established. These organisations were all abolished by the Soviet Union in 1940, but after Estonia regained independence, they were reconstituted in 1991. Today the Kaitseliit is three times larger than the standing Estonian Army and would act as a key component in meeting any threat to Estonian independence.

Hiiumaa Kaitseliit

Note: A subsequent post will look at the Latvian Aizsargu Organizācija and the Estonian Kaitseliit as well as the relationship between Finland on one hand, and Estonia and Latvia on the other.

It should also be noted that in the early history of the United States there were a number of militia groups that bear a striking resemblance to the Finnish Suojeluskunta (Civil Guard), but over time these institutions have died away or have been swallowed into larger and more “orthodox” defense organizations such as the US National Guard. The Civil Guard in Finland has in fact been compared by many to the “modern” National Guard Units of the United States, but this is not accurate nor is this a good comparison. There are some similarities but the differences are also significant. While the principle behind the Civil Guard is not unique to Finland it is very different than what most in the West are accustomed to hence the confusion many have on the history and role of the Civil Guard.

II – Bitter Winners and Sore Losers – Reds and Whites in the 1920s

As the turmoil of the Great War and the Revolution in Russia finally calmed down along the Finnish borders in the early 1920s, many Conservatives had already begun to feel that the “War of Liberation” had ended too soon and in an inconclusive fashion. New critics joined in the public discussion by openly accusing the political leadership of wasting what some now saw as a unique opportunity for territorial expansion into the historic Finnish lands of Eastern Karelia by signing the Treaty of Tartu – some went even further, cursing the moderate politicians for their decision to stay out of the Russian Civil War, thus allowing the Bolsheviks to retain their hold on Petrograd and indirectly helping them to win. Back at home many felt there were still accounts to be settled with the radical left. The survival of the SDP as the strongest political force in the country was especially galling for many White veterans of the Civil War.

Akateeminen Karjala-Seura poster

In the 1920s, the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura (the Academic Karelia Society or AKS) soon became the dominant group among Finnish university students after three volunteer veterans of the Heimosodat (Kinship Wars) had created the organisation in March 1922 (and in fact the AKS controlled the student union of the University of Helsinki from the mid-1920s right up to 1944, when, OTL, it was disbanded). Its members often retained their membership after their student days ended and the AKS therefore quickly expanded its influence among young civil servants, teachers, lawyers, physicians and clergymen as well as in the officer-class of the Army throughout the country during the 1920s. Most Lutheran clergymen had been strongly pro-White during the Civil War and the influence of the AKS further increased the nationalistic character of the Finnish Lutheran Church – and the Lutheran Church was one of the most influential organizations for the changing of public opinion in the country. The AKS and its propaganda focused on “uniting the oppressed tribe of Karelians with rest of Finland” strongly affecting the worldview of the entire first generation of educated Finns living in independent Finland, resulting in a common mood that was relentlessly anti-Soviet and expansionistic.

The AKS’ 20 year anniversary book (1942): “Me Uskomme / We Believe”.

The AKS’ 20 year anniversary book (1942): “Me Uskomme / We Believe”. OTL, the organization was banned in 1944 – after the Finnish government broke its alliance with Germany — as a “fascist” organization. One of the important goals of the AKS was to unite the Finno-Ugrian-speaking areas of Soviet Karelia which were traditionally Finnish into Greater Finland. Stalin sent many thousands of Karelian and Ingrian Finns to their deaths in Siberia and Central Asia both before and after the war, and brought in Russians to replace them. Today, in most of Soviet Karelia and Ingria only Russian is spoken – after 2.000 years of being the Finnish heartland, almost no Finnish peoples remain.

The political and philosophical ideology of the AKS had its main roots in the philosophy of the 19th century Finnish statesman Johan Vilhelm Snellman, who emphasized a strong national state and the need to bring the Finnish language into the forefront of Finnish cultural life, which was at that time dominated almost exclusively by the Swedish language. The nationalistic ideology of the AKS also stemmed from the common European discussion of national rights based on the 14 points of President Wilson. The experience of the Finnish Civil War bolstered a deep anti-socialist sentiment in Finnish nationalist circles of that time. One of the slogans the AKS used was “Pirua ja Ryssää Vastaan!” (“Against the Devil and the Ruskies!”) where the devil is a reference to the Society’s main domestic enemies, the socialists and the communists.

Despite holding views that might be seen as similar to those of the Fascist movement of Italy, there were no influences from abroad – the AKS was founded well before the Fascist march on Rome and its origins were purely domestic. The group was founded by Elias Simojoki, Erkki Räikkönen and Reino Vähäkallio. The initiation ceremony involved among other things kissing the flag of the AKS, within which was sown the bullet that Bobi Siven had shot himself with (Sivén, a Finnish nationalist, had shot himself in protest when Finland relinquished control of the Repola and Porajärvi Parishes to the Soviet Union in accordance with the Treaty of Dorpat). All members taking the oath for the order kissed the flag and the bullet in the initiation ceremony.

Akateeminen Karjala-Seura. Sällskapet odlade flitigt olika ritualer. I fanan som användes i sådana sammanhang hade man sytt in den kula som ändade martyren Bobi Sivéns liv. Här ett fackeltåg vid dennes grav på tioårsdagen av organisationens grundande 22/ 2 1932.

Many of the founders of the AKS were veterans of the Karelian wars (the Heimosodat) and thus had first-hand knowledge of the plight of the Karelian-speaking population in Soviet Karelia. The Karelians were considered to be a part of the Finnish heimo (folk) and their fate was of the utmost importance for the AKS. The Academic Karelia Society’s program was centered on their main demand: the liberation of Eastern Karelia from Soviet Russia and the freeing of the Karelian kinfolk. Working towards this goal was mainly done by propagandist efforts to keep the matter in the public eye. The AKS also organized aid to Finnic minorities in Soviet Russia and refugees from there and promoted cultural efforts to help the Finnish-speaking minorities of northern Sweden and Norway. They also tried to cultivate a closer friendship between the newly independent states of Finland and the Finno-Ugric states of Estonia (and to lesser degree Hungary).

Domestically the AKS was an emphatic proponent of a strengthened army and for strict restrictions against Socialists and Communists, although at the same time the AKS stressed the need for improving the lot of the working classes in the interests of the national community. It also promoted the Finnish language becoming the first language in the country, especially in the Universities and in the state bureaucracy. Initially the group was ambivalent towards democracy but under the chairmanship of Vilho Helanen it came to oppose the concept. As a result, in the 1930s, the AKS was an ally of the ultra-right Patriotic People’s Movement party (IKL). The AKS also maintained close ties with a militant secret society called Vihan Veljet (literal translation from Finnish: “Brothers of Hate” – this was a militant clandestine group within the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura (AKS). Members swore a blood oath to foster and uphold hatred toward the Russian people. Some authors claim that Vihan Veljet was actually a group inside the AKS, not a separate organization, but there is not much evidence either way).

OTL, after the end of World War II, the organization was labeled “fascistic” and officially disbanded on the order of the Allied Control Commission, and the archives of AKS were hidden or destroyed. Prominent former members include many academics, bishops, business leaders, generals and politicians (e.g. president Urho Kekkonen). Many officers of the Finnish army during the wars of 1939–1940 and 1941–1944 were members of the Society.

Note: By way of further background, a subsequent post will give a brief overview of the historically Finnish lands within the Soviet Union, their history and their subsequent fate at the hands of the Russians both before and after WW2.

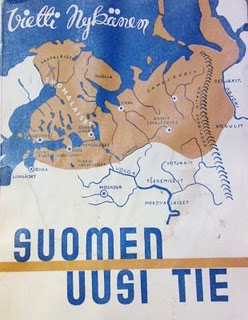

“Greater Finland”

This map gives some idea of the areas that the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura rightly considered to be part of “Greater Finland” by virtue of being traditionally inhabited by Finno-Ugric speakers. In particular, the territories along the eastern border of Finland to the White Sea, which had for as long as history has been recorded been populated by Finnish Karelians were called Eastern Karelia in Finland. Most of the poems in the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, were collected from this area and as the ideas of Finnish nationalism gained ground at the end of the 19th century, supporters of a Great Finland hoped that the territory would be incorporated to Finland. The Finnish populations of theses territories were not at the time inspired by the same idea, most of them were members of the Russian Orthodox Church rather than Lutherans and preferred the traditional Russian administration, referring to the Finns from Finland as “Swedes”.

At the beginning of 1918, the supporters of “greater Finland” began to organize expeditions in order to persuade the Eastern Karelians to join Finland. The Senate and the Commander-in-Chief (Mannerheim) supported the projects. Mannerheim even went a step further and promised not to put his sword into the scabbard (the Order of the Day of the Sword Scabbard), until White Karelia and Aunus were liberated from Lenin’s “hooligans”. This led to fighting between the Allies and Allied-supported forces and the Finnish expeditionary forces in the region as the Allies sought to keep the Murmansk Railway in Russian hands so as to enable military supplies to continue to be transported to the Russian military as the Allies endeavoured to keep the Russians in the War against Germany. Perhaps unfortunately for the dreams of the Finnish nationalists, the Finnish alliance with Germany at the time firmly placed Finland in the enemy camp and meant that the Allies actively fought against them in 1918.

After Germany and Russia signed the Brest Peace Treaty on 3 March, 1918, the policy of the Finnish government became more cautious. In April and May 1918, preparations were made in Mannerheim’s headquarters for an operation in Aunus, in order to encourage “Finnish” thinking and to assist the Russian White forces in the liberation of St Petersburg from the Bolsheviks. The Senate, however, prevented this project from being carried out. Mannerheim believed that the White Russians would show their gratitude by ceding Eastern Karelia to Finland. The idea of incorporating Eastern Karelia into Finland became more intense during the Heimosodat (Kinship War) expeditions of 1918-1922, and afterwards when the members of the Akateeminen Karjala Seura (Academic Karelia Association), became rather more powerful and influential. After 1922 Mannerheim did not publicly give his support to these projects and in the 1930s they were overshadowed by other issues, but as we will see, the issue again came to the fore after the Winter War broke out.

A Note on leading members of the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura (Academic Karelian Society)

Vilho Veikko Päiviö Helanen: (24 November 1899, Oulu – 8 June 1952, Frankfurt, West Germany). Vilho Helanen was a Finnish civil servant and politician. A student as the University of Helsinki he gained an MA in 1923 and completed his doctorate in 1940. From 1924 to 1926 he edited the student paper Ylioppilaslehti and around this time also joined the Academic Karelia Society. He served as chairman of the group from 1927-8, from 1934-5 and again from 1935-44, helping to turn the Society against democracy. Helanen visited Estonia in 1933 and was amazed at the high levels of popular support for the far right that he witnessed there, in contrast to Finland where it was a more marginal force. As a result he was involved in the coup attempt of the Vaps Movement in Estonia in 1935. Helanen was a major inspiration for the Patriotic People’s Movement and a close friend of Elias Simojoki, although he did not join the group. He formed his own group, Nouseva Suomi, in 1940 which, despite his earlier radicalism, became associated with the mainstream National Progressive Party. Rising to be head of the civil service during the Second World War he was imprisoned after the war for treasonable offences. Following his release he worked for Suomi-Filmi and also wrote a series of detective novels.

Lauri Elias Simojoki (28 January 189?, Rautio – 25 January 1940)

Lauri Elias Simojoki (28 January 189?, Rautio – 25 January 1940) was a Finnish clergyman who became a leading figure in the country’s far right movement. Himself the son of a clergyman, as a youth he saw service in the struggle for Finnish independence and then with the Forest Guerrillas in East Karelia. A student in theology at the University of Helsinki, he became involved in the formation of Academic Karelia Society, serving as chairman from 1922-3 and secretary from 1923-4. He advocated the union of all Finnish people into a Greater Finland whilst in this post. Strongly influenced by Russophobia, the student Simojoki addressed a rally on ‘Kalevala Day’ in 1923 with the slogan “death to the Ruskis”, after accusing Russia of dividing “the Kalevala race”. Simojoki was ordained as a minister in 1925 and he held the chaplaincy at Kiuruvesi from 1929 until his death. He became involved with the Patriotic People’s Movement and, in 1933, set up their youth movement, Sinimustat (The Blue-and-Blacks), which looked for inspiration to similar movements amongst fascist parties in Germany and Italy. The movement was banned in 1936 due to its involvement in revolutionary activity in Estonia, although Simojoki continued to serve as a leading member of the Patriotic People’s Movement. He was a Member of Parliament from 1933-1939 and founded a second youth group, Mustapaidat (the Black Shirts), in 1937, although this proved less successful. When the Winter War broke out in 1939 Simojoki enlisted as a chaplain in the Finnish Army. He was shot on active duty, while putting down a wounded horse in no man’s land, and died of his wounds on 25 January 1940.

Erkki Aleksanteri Räikkönen (August 13, 1900, St Petersburg – March 30, 1961) was a Finnish nationalist leader. He attended the University of Helsinki before taking part as a Volunteer in the ill-fated mission to secure independence for Karelia in 1921. Like most of those who took part in this action he joined the Academic Karelia Society (AKS), in his case helping to found the movement along with Elias Simojoki and Reino Vähäkallio. He quit the AKS in 1928 to join the Itsenäisyyden Liitto (Independence League), a group that had been formed by Pehr Evind Svinhufvud, Räikkönen’s most admired political figure. Räikkönen took this decision in response to the banning of the Lapua Movement, a move that had left the far right in Finland without a wide organisational basis (groups like the AKS only having a small, elite membership). Along with Herman Gummerus and Vilho Annala, Räikkönen was the founder of the Patriotic People’s Movement (IKL) in 1932. He would not stay a member long however as the group soon became purely Finnish (isolating the Swedish-speaking Räikkönen) and moved closer to Fascism, which he opposed. After leaving the movement he contented himself with editing the journal Suomen Vapaussota, whilst also becoming involved in the Gustav Vasa movement, a right wing organization for Finland’s Swedish-speaking population. For a long time, he was also President Svinhufvud’s private secretary. He ultimately emigrated to Sweden in 1945 and lived out his life there in retirement.

And on the other side of the political spectrum…. the Punainen, the Reds….

March 12, 1930. The first company of the Karelian Jäger Battalion

On the other side of the political spectrum, the Finnish Communists equally felt that the Civil War had been only the beginning of their struggle against their counter-revolutionary opponents. Openly backed by a steadily strengthening Soviet Union, the Communist Party of Finland, the SKP, trained new “Red” military forces in Soviet Karelia where radicalized former Social Democratic leaders and over 5000 refugees from the Red side of the Civil War were actually promoting virtually similar goals to their Conservative opponents – the unification of Eastern Karelia and Finland, except in their case, under the Communists. As a result of their work Finnish was the second official language in the new Karelian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, and propaganda broadcasts from the Petroskoi (Петрозаво́дск) Radio openly threatened listeners in Finland that the day of reckoning would soon come. New cadres of Red Finnish officer cadets were trained annually in Leningrad, and after the failed uprisings of the 1920s the Red Army even organized a Karelian unit of their own in the form of the Karelian Jaeger Brigade (Каре́льская е́герская брига́да). Because of the fresh memories of the Heimosodat (Kinship Wars) and the postwar status of Eastern Karelia as a “Red Piedmonte” where Finnish revolutionaries were clearly preparing for revenge, the official relations between Helsinki and Moscow were thus understandably icy.

1928. The Karelian Jäger Battalion on parade in Petrozavodsk

After the suppression of the Karelian uprising of 1921-1922 the Central Committee of the C.P.S.U.(B.) on March 5th 1922 decided to start Finnicising the Karelian Labour Commune. The leadership of the Karelian Labour Commune went to the so-called “Red Finns”. The Finnish language became the official language in the Commune and was used as the main language in Karelian schools and as the language used for cultural and political work among Karelians. On July 25th 1925 the Karelian Labour Commune was transformed into the Autonomous Karelian Soviet Socialist Republic (AKSSR). From a political perspective the “Red Finns” saw the AKSSR as the outpost of the “world revolution” in the North of Europe. There objective was to expand the AKSSR into “The great Red Finland” and even “Red Scandinavia”.

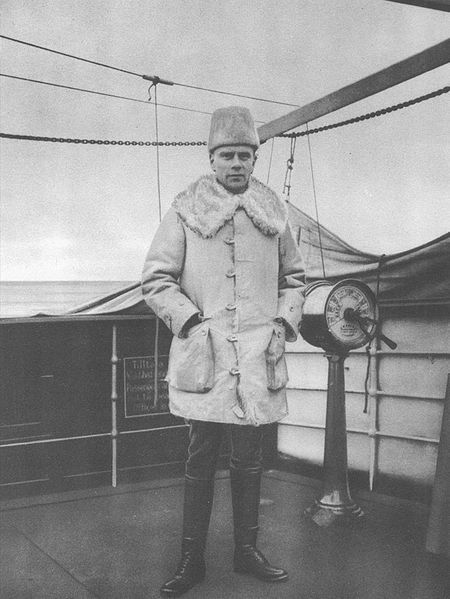

Eyolf Igneus-Mattson was born to a well-to-do Swedish family on the Åland Islands (Finland) in 1897.

This policy also included the creating of a special national military unit within the AKSSR. On October 15th 1925 in Petrozavodsk the Karelian Jäger Battalion was established personally by the Chairman of the AKSSR Soviet People’s Commissar Edvard Gylling. The battalion consisted of four companies, with the battalion quarters in Petrozavodsk, in the buildings of the former Orthodox theological seminary on Gogol Street. The first battalion commander was Eyolf Igneus-Mattson, holding the position till 1928. The first commissar was A.Mantere. In 1927 he was replaced by Urho Antikainen. In October 1931 “due to the aggressive external policy of Finland towards the USSR” and because of the high number of convicts in the territory of the AKSSR, the battalion was transformed into the Karelian Jäger Brigade. The Brigade formation was completed by December 25th 1931. The brigade commander, by recommendation of Edvard Gylling, was Eyolf Igneus-Mattson.

Eyolf Igneus-Mattson was born to a well-to-do Swedish family on the Åland Islands (Finland) in 1897. He graduated from the Higher Technical School in Helsinki and participated in the Red revolt, after the defeat of which he escaped to Soviet Russia, where he finished military training at the Petrograd International Military School. From the summer 1919 he was the commander of the 2nd Battalion of the 164th Infantry Regiment (in August 1919 renamed the 2nd Finnish Regiment), he took part in the battle at Sulazhgora Heights and was decorated with the Order of the Red Banner. He graduated from the Military Academy of the Red Army. From 1925-1928 he was the commander of the detached Karelian Jäger Battalion, from 1931-1934 commander of the detached Karelian Jäger Brigade. In November 26th 1935 he was promoted to the rank of Kombrig (Brigade General). In 1936 became the head of the sub-faculty of general tactics in the M.Frunze Military Academy of the Red Army. In May 28th 1936 he was arrested. He was released in 1946, rehabilitated in 1957 and died on May 25th 1965.

The Karelian Jäger Brigade consisted of two Jäger Battalions (the Petrozavodsk and the Olonets), one artillery battalion, one field company and one communications company. The Brigade was a territorial military unit – the soldiers served their five-year terms near their homes by way of serving several 8 to 12 months musters. In the case of mobilization two more battalions would be formed (the Zaonezhsky and the Vepsky). In June 1932, when the Karelian registration and enlistment office was liquidated, the Brigade Headquarters was supplemented with enlistment and quartermaster departments. The territorial formation of military units was usual for the Red Army at the time, but the name “Jäger” was unique within the Red Army. It was proposed by the leadership of the AKSSR as an analog of the Finnish jäger units. Another big difference was that all commanding posts it the Brigade were held by Finns and Karelians.

Early 1930’s. The Red Army’s Karelian Jäger Brigade on the march

The Karelian Jäger Brigade was the only military unit on the territory of the AKSSR. In the case of war with Finland the Brigade operational plans were to cover Petrozavodsk from a Finnish invasion. The last stand, as in 1919, was planned to be the Sulashgora Heights. As an alternative there were plans to move the Brigade to the Kola Peninsula to repel any British landing forces. The activities of the “Red Finns” were carried on to a background of increasing political repression. In the spring of 1930 the OGPU arrested a group of “Red Finns” holding commanding positions in the detached Karelian Jäger Battalion. A second wave of arrests began in 1932 and involved mainly the officers of the 2nd (Olonets) Battalion of the detached Karelian Jäger Brigade. 20 men were shot as a result of the investigation for “counterrevolusionary rebel organisation”.

In 1933 the OGPU “disclosed” the so called “plot of the Finnish General Headqurters”. Some of the commanding officers of the detached Karelian Jäger Brigade were subjected to arrest and removed from their positons. From January 1934 a Josef Kalvan was appointed as brigade commander (known as “The Latvian”, Kalvan was born in January 25th, 1896 to a peasant family. He was decorated with the three Orders of the Red Banner. In November 26th 1935 he was conferred the rank of Kombrig (Brigade General). He was arrested on December 2nd 1937 and executed on September 12nd, 1938) and in 1935 the “Red Finns” were removed from the all leadership positions in Karelia and the detached Karelian Jäger Brigade was disbanded. At the end of 1935 the 18th Yaroslavl Infantry Division was stationed on the territory of AKSSR, with some units of the Karelian brigade now incuded within this Division. The majority of the Officers, NCO’s and Soldiers of the Karelian Jäger Brigade were killed during the mass political repressions of the later 1930’s.

The Karelian ASSR NKVD “… found and destroyed a counterrevolutionary rebel organisation. This organisation emerged in 1920 with the coming to Karelia of the group of bourgeois nationalists: Gylling, Mäki and Forsten, that held leadership positions on the Karelian Revolutionary Committee. By spreading their counterrevolutionary activity and including into it Finnish and Swedish political emigrants, former members of Finnish Social-Democratic Party Rovio, Matson⁸, Vilmi, Usenius, Saksman, Jarvimäki and others this counter-revolutionary group seized the main Party and Soviets posts in Karelia. The activities of this counterrevolutionary organisation were directed towards the intervention and capture of Soviet Karelia by Finland…Holding the main commanding posts in Karelia this nationalist organisation organised … preparation of armed uprising by the means of … creating of the infantry jäger brigade, staffed by national commanding and political officers. In this brigade they spread their counterrevolutionary propaganda and used it as a base for creating rebel organisations on the all territories of the Republic, this activity was performed in close junction with the “rights”, working in Karelia…”

The draft of the “unreliable” Finns and Karelians into Red Army was stopped by 1938. By the end of summer 1939 the few remaining Finnish officers were called from the reserve and in the middle of November there was a mass draft of Finns and Karelians. At the time in Petrosavodsk was formed the 1st Infantry Corps of the so called “Finnish People’s Army”… “(The Corps commander and Minister of Defence in the government of the puppet Finnish Democratic Republic was Komdiv (Division General) Aksel Anttila – former Karelian Jäger Brigade Headquarters Deputy Chief).

An interesting Case Study: Edvard Gylling, Chairman of the AKSSR Soviet People’s Commissar and “Karelian Fever”

Edvard Otto Vilhelm Gylling (30 November 1881, Kuopio – 14 June 1938) was a prominent Social Democratic politician in Finland and later the leader of Soviet Karelia. He was a member of the Finnish Parliament for the Social Democratic Party of Finland from 1908–1917 and was active during the Finnish Civil War as the Commissar of Finance for the revolutionary “red” Finnish government. On 1 March 1918, when a Treaty between the socialist governments of Russia and Finland was signed in St Petersburg, the Treaty was signed by Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin from the Russian side and by Council of the Peoples Representatives of Finland Edvard Gylling and Oskari Tokoi. After the Reds lost the war, Gylling fled to Sweden but later moved to the Soviet Union. He became one of the main leaders of the Karelo-Finnish ASSR as Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Karelo-Finnish SSR from 1920–1935. He was accused of nationalism, removed in 1935 and arrested in 1937. There are some contradictions concerning Gyllings death. According to earlier Soviet sources, Gylling died in August 1944, but according to other sources he was actually executed earlier, 1940 or 1938. According to the most recent information, the most likely date of his execution was 14 June 1938.

Gylling more than anyone else was responsible for what has become known as Karelian Fever. Karelian Fever struck in the United States and Canada in the early 1930s, affecting mainly, but not exclusively, first generation Finnish-Americans. Finnish immigrants to North America were divided roughly into two categories: the Church Finns and the Hall Finns; the latter tended to lean to the left politically and some were active Communists. When recruiters went to the Halls to extol the virtues of the Russian Soviet way of life, many were tempted to leave America. The Depression was making life very difficult for farmers, miners, woods workers and small business owners; they were “experiencing the ruthless exploitation of capitalism.” At the time, an interesting situation prevailed in Karelia, the Russian province located near the southwestern border of Finland. Dr. Edvard Gylling, a brilliant Finnish Communist, had become the prime minister of the province and hoped to make it a mainly Finnish-speaking area. In the first Russian Five-Year-Plan strategists assigned production quotas for Karelia which Gylling knew could not be met without financial help and skilled workers from other countries, specifically the United States and Canada. So the call went out for Finnish-speaking construction workers, loggers and fishermen to come to the “workers’ paradise” and bring money and equipment with them.

Inasmuch as the first generation of American Finns could read English only with difficulty, they got a very slanted picture of conditions in Russia from the Finnish Communist papers, the Tymies and Eteenpain. According to Mayme Sevander who has done serious research on the topic, as of 1996 she had identified 5,596 people who responded to the call, selling their belongings in North America and taking the money to Karelia. Boatloads of several hundred sailed together to the strains of the Internationale and the waving of red flags. They were an idealistic people, willing to work hard to establish a new society. The largest groups left in 1930-31, but by 1934 the size of the groups had diminished to as low as eight or ten. Of the almost 6,000 who emigrated, only 1,346 returned. Seven-hundred-ninety men and sixty-three women are known to have been executed during Stalins purges; many others died in labor camps of starvation during the Finnish-Russian War and during World War II. Some still live in Karelia. (See “From Soviet Bondage” by Sevander, 1996).

If you’d like to read more on this subject, try the following books:

• The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia by Tim Tzouliadis

• They Took My Father: Finnish Americans in Stalin’s Russia by Mayme Sevander

• Karelia – a Finnish-American Couple in Stalin’s Russia by Anita Middleton

• Soviet Karelia: Politics, Planning and Terror in Stalin’s Russia, 1920-1939 by Nick Baron

Edvard Gylling

Returning now to Edvard Gylling any explanation of Karelian Fever must begin with the life and career of Edvard Gylling, whose life can be divided into two halves. He was born in Kuopio, Finland in 1881 and up to June 1918 he resided in Finland. He grew up in a prosperous middle class family and became steeped in Finnish patriotism and Finnish cultural identity early in life. Gylling grew up in a family of women, his mother and sisters raised him as his father was often away on assignment for the Finnish state railway. On the family estate he learned his love for the countryside and became aware of the poverty that then afflicted so many in rural Finland. Gylling entered the University.of Helsinki in 1900 at the height of Russification under the hated Russian Governor General Bobrikov. He joined the Old Finn Party, believing, like other members of that party that conciliation toward the Russian authorities would encourage Bobrikov to mitigate his policies. Gylling won a scholarship to study in Germany for 6 months in 1904. He returned to Finland to find his homeland, the Grand Duchy of Finland, in a state of revolution. Gyliing had been exposed to socialist ideas in Germany and on his return he quickly joined the Finnish Social Democratic Party.

Starting from 1905, Gylling became prominent in the Finnish Social Democratic Party. He entered Parliament and became the party’s expert on agrarian matters. He also continued his academic career, writing his doctoral dissertation in 1909 and joining the faculty of the University of Helsinki in 1911. Gylling became a pioneer in the application of statistical methods to historical research and also became the official demographer of the city of Helsinki, conducting a census for the capital and for Finland as a whole. Such works are still widely consulted. Gylling’s publications in the first decade of the 20th century concerned the sorry plight of the Finnish crofters who were emigrating to the U.S. in large numbers. He also wrote about the exploited state of the Finnish peasantry when Finland had been a Swedish province. Gylling addressed the Finnish Crofter’s Association and drafted the Agrarian Program for the Finnish Social Democratic Party. His work on agrarian issues and his statistical research made him acutely aware of how serious were Finland’s demographic losses, primarily to the U.S., in the period 1894-1914.

In 1906 Gylling was engaged to Fanny Achren. Both had been raised in central Finland and had a strong love for rural Finland. Edvard and Fanny were married on June 14, 1906. Gylling would be executed on their 32nd wedding anniversary by the Soviet regime as a bourgeois nationalist. His wife’s execution would follow shortly thereafter.

Sosialistinen Aikalislehti was Finland’s first Social Democratic journal, for which Gylling served as editor in chief from 1906-1908. He was a prominent member of the SD party but also decidedly a moderate and a non-Marxist who wanted to work in parliament via coalitions with bourgois parties. With the Russian revolution of 1917, Gylling sought first and foremost autonomy for Finland if not outright independence. The Provisional Government in Russia refused to grant Finland independence but the Bolsheviks did in December 1917. Despite Gylling’s efforts at mediation between his own countrymen, civil war broke out between radical socialists and members of the working class opposing the large landowners and the middle class. Gylling deplored the conflict, seeing that it would only compound the demographic losses already incurred from emigration. In whatever he did Gylling found a unifying principle in Finnish nationalism. He deplored the emigration from Finland of the early 20th century just as he deplored the Finnish civil war. Both phenomena undermined the demographic stability of Finland. In politics Gylling was committed to compromise and negotiation and believed that even the most contradictory principles could be reconciled. He very reluctantly accepted the appointment as Member of the Revolutionary Government and Minister Plenipteniary for Finances and was the last high-ranking member of the Red government to leave Finland, doing so in May 1918. The victorious White government refused his offer to negotiate, and put a price on his head and as a result, Gylling, disguised as a woman, escaped to Stockholm where he spent the next two years of his life, from 1918-1920.

Gylling spent two years in Stockholm before receiving permission from Lenin himself to head the new Karelian Workers’ Commune. In Stockholm Gylling had somewhat reluctantly joined the new Finnish Communist Party founded by his former school mate O.W. Kuusinen. Lenin wanted Soviet control over Karelia secured. Gylling wanted to create a Finnish homeland under the aegis of the new Bolshevik government. He negotiated from Lenin agreements on the use of the Finnish language and restrictions on the immigration of Russians to Kareliaand in the process transformed himself from a prominent Finnish Social Democrat to an important Soviet official as the Permanent Chairman of the Karelian Council of People’s Commissars. In the Soviet Union Gylling quickly became the most important political figure in Karelia. By 1923 he was Permanent Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars.

The road to power in Karelia had not been direct, however. From Stockholm in 1918, he had written Lenin of a plan to make Karelia, in the far northwest corner the new Russian Republic, a place of refuge for Red Finns fleeing the victorious Whites after the Finnish Civil War. Lenin was not interested, but in 1920 when Lenin sought to secure Soviet control of Karelia before negotiations that fall which would determine the Soviet northwest border, Gylling’s earlier proposal appeared useful. He invited Gylling to Moscow where the two conducted negotiations on Karelia’s future status. Lenin promised that Karelia would retain a Finnish character, and Russian immigration would be kept to a minimum. Gylling acquired a measure of budgetary autonomy for Karelia and made Finnish equal to the Russian language in official transactions. In fact, in schools and in official business as well as in record keeping, Finnish replaced Russian as the language of Karelia.

Gylling wrote an article in 1925 on his plans for the future development of Karelia, revealing his concept of Karelia as a distinctive region of the Soviet Union, geographically, geologically and economically bound to the Finno-Scandinavian plateau of which it was an integral part. For Gylling, Karelia’s proximity to Finland and its tradition as the place where the events of the Finnish national epoch, The Kalevala, had occurred were far more significant than Karelia’s position as a constituent part of the Soviet Union. Gylling maintained the Finnish character of Karelia through the 1920’s. With the imposition of Stalin’s First Five Year Plan in 1929, Russian in-migration in the form of a large, new work force would surely change the ethnic character of Karelia and do so dramatically. Gylling decided to recruit an ethnically Finnish work force in North America. He had seen the North American Finnish diaspora form earlier in the century. Since the 1920’s it had often sent aid to Karelia.

In late 1928 or early 1929, Gylling travelled to Moscow to argue for the continued ethnic and economic autonomy for Karelia despite pressures imposed by the First Five Year Plan calling for fast paced industrial development. Gylling feared that the high industrial targets would mean the recruitment of a Russian work force that would dilute the Finnish character of Karelia. K. Rovio, head of the Karelian Communist Party, also shared Gylling’s commitment to a Finnish Karelia. In March 1931 Gylling and other prominent figures from Karelia again travelled toMoscow to make a special case for the right to recruit workers from abroad. Gylling drafted the petition requesting permission to invite lumberjacks and others skilled in the timber industry to come to Karelia and assist in the exploitation of Karelia’s “green gold.” At the Sixteenth Party Congress held the summer before, Molotov had called for inviting foreign workers and experts to contribute to the Soviet Union’s industrial development as part of the First Five Year Plan. Gylling now built on Molotov’s suggestion (which came direct from Stalin) to plead for a foreign, i.e. Finnish work force for Karelia. Gylling knew that such a work force existed in North America. He had calculated the demographic losses as a historian and statistician in Finland and now he hoped to recruit that work force for Karelia in order to maintain Karelia’s Finnish character. He would conduct such recruitment under the protection of Molotov’s recent directive. In effect, Gylling would recruit the Finnish North American diaspora to his Finnish homeland of Karelia.

However, by the end of the 1930’s Gylling and the North American Finns whom he recruited to live and work in Soviet Karelia would come to share the same fate. Gylling’s position in Karelia began to deteriorate in 1935. In early 1935 Gylling presented his production goals for Karelia in Moscow. He faced a hostile audience – Moscow was about to withdraw Karelia’s budgetary independence – which had been negotiated by Gylling in the early 1920’s. Important members of the Soviet government had begun to question the presence of so many North American Finns in Karelia, a border region next door to Finland, which was known to be hostile to the Soviet Union. In October 1935 he was forced to sign a denunciation of Finnish nationalism in Karelia, the very policy that he had earlier maintained with Moscow’s support. The following month he was recalled to Moscow where he joined Rovio, who had been sent there in August. Both men were replaced by Russians. Some of the Finnish Americans believed that Gylling had been promoted, not understanding that their own security was now as precarious as his. 1938 saw a dramatic turn in the fortunes of Gylling and the North American Finns whom he had recruited to Karelia. Gylling was arrested and shot in June 1938. As of July 1 1938 the Finnish language was outlawed and in Karelia Finnish newspapers and the Finnish radio station were shut down and Finnish books were burned.

Finnish Americans were now caught up in the holocaust that had begun in late 1936 in the rest of the Soviet Union. Many of those Finnish Americans who had joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union were arrested and executed. Most of the children were spared, that is anyone in the Finnish American community under age 21 by 1938. There were, however, tragic exceptions. A 16 year old Finnish American studying in the Petrozavodsk Conservatory was arrested and shot. The secret police as elsewhere had a quota of victims to meet. But in Karelia another element came in to play: circumstances had given those who envied the work ethic, prosperity, and higher standard of living of the Finnish Americans the opportunity to exact revenge. The newly appointed Russian administrators of Karelia now exacted a terrible toll on the North American Finns, who had worked so hard under Gyllings leadership.

Edvard Gylling was executed in June 1938. His wife, Fanny, was executed shortly thereafter. Of the almost 6,000 North American Finns who emigrated to Karelia, only 1,346 returned. Seven-hundred-ninety men and sixty-three women are known to have been executed during Stalins purges; many others died in labor camps of starvation during the Finnish-Russian War and during World War II. Some few escaped over the border to Finland or managed to return to North America by other means. Some still live in Karelia.

You can read some of the survivors stories here: http://www.d.umn.edu/~apogorel/karel…vors.html#ruth

Obviously, news and information trickled across the border, with refugees and escapers from the Soviet Union providing some information. It was not just a perceived threat that Finland faced. But from immediately after the end of the Civil War, with conflicts still endemic along the border and the Bolsheviks consolidating power, Finnish Conservatives responded by further improving their efforts to create a new and stable status quo within the country. Their program of creating a new Finland was predicated on the support of the paramilitary Suojeluskunta organization, the Civil Guards militia that soon became one of the key cornerstones of post-war Finnish society. “We must win the working class over to the side of our nation!” was one of the key propaganda slogans of the AKS (and the Army), and the chief aim of all civic activity in Finland during 1920s was indeed focused on improving the sense of Finnish national unity that had been tarnished by the Civil War. This was to be achieved by binding all segments of society together, “uprooting” Communism in the process. The Suojeluskunta and its associated female volunteer organization Lotta Svärd formed an umbrella group organizing various kinds of activity: training manuals, lectures, citizenship courses, national youth organizations (Sotilaspojat for boys and Pikkulotat for girls), sport clubs and actual military training and practices. The unifying theme in both organizations was the pessimistic worldview where an invasion from the East, from the Soviet Union, was not only probable, but imminent (a viewpoint that, given the activities on the Soviet side of the border and subsequent events, was certainly valid).

II – The Suojeluskunta in the 1920’s

At the same time, the end of the Civil War had brought the Suojeluskunta a challenge. The existing Suojeluskunta organizations had been originally organized as voluntary units for maintaining local security in the chaos of the collapse of the Tsarist Russian Empire, a situation which was no longer valid. With the ending of the Civil War and the White victory, Finland was now truly independent, but with the Soviet Union across the border, with Red Finns organizing and training in Soviet Karelia, and with a dissident working class, many of whom had actively fought for the Reds in the Civil War, Finland needed to safeguard itself against both interior and exterior enemies. The Finnish Army was still very small as we have seen, and as a “Cadre” Army could not have coped with any foreign attack on its own. Having an internal paramilitary organization which would guarantee the safeguarding of Finland against external and interior enemies was seen as important – in the event of external conflict, this organisation would provide trained reinforcements to the Army, and in the event of internal conflict, the organisation could be counted on to be politically reliable and support the Government in putting down any renewal of armed internal opposition.

The Suojeluskunta was seen as the organisation which would enable these security objectives to be met, but to do this the organisation needed to be redesigned and uniformly rebuilt nation wide. Redesigning and restructuring the new organization raised a number of critical questions, debate over which continued well into the 1920s. The more important of these questions included:

- Should Suojeluskunta membership be voluntary or obligatory?

- What should be the main missions of the Suojeluskunta?

- What relationship should the Suojeluskunta have to the Finnish Army, the Finnish political system, and local authorities?

On the 4th of July of 1918, representatives of 171 local Suojeluskuntas gathered in the town of Jyväskylä. The decisions and resolutions made in Jyväskylä had a profound impact on the future of the Suojeluskuntas and greatly influenced the first piece of legislation on the Suojeluskunta, which was a statute legislated by the Finnish Senate on 2 August 1918. The statute was short in text and rather vague on some matters, but it cleared up things considerably and put in place the legislative groundwork needed for creating the new organization. At the same time it recognized the status of the Suojeluskuntas on the part of the State. Matters covered in the legislation included:

- The Suojeluskunta was defined as a State-wide voluntary organization with local and district levels. Each local area would have a local Suojeluskunta;

- The country would be divided to Suojeluskunta districts, all of which would include several localities. Basic organizational structure was defined, with Local and District HQ’s and Chiefs, as well as how these should be created;

- The Suojeluskunta organization would not be part of the Army, but would be a separate entity having its own Commander-in-Chief;

- Membership eligibility requirements were set as being “trustworthy males of at least 17 years of age”. The process of selecting members was that they must be volunteers with a recommendation. Members could be active or passive;

- The Suojeluskunta oath was introduced for all Suojeluskunta;

- The Suojeluskunta were given rights to accept donations and to own property.

The Organizational and Command Structure of the Suojeluskunta

The statute also set out the organizational and command structure for the Suojeluskunta (usually abbreviated to Sk). Initially, there was no overall HQ, and in military matters the Suojeluskuntas were directly subordinate to the Defense Ministry. The statute made the leader of the Senate’s Committee of Military Matters, Major-General Wilhelm Thesleff the first Commander-in-Chief of the Suojeluskuntas and gave the Suojeluskuntas their own representative in the Defense Ministry.

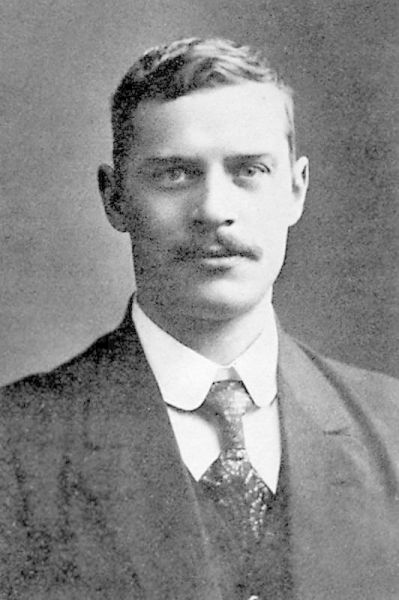

Major-General Wilhelm Thesleff

Major-General Wilhelm Thesleff (July 27, 1880 in Vyborg – March 26, 1941 in Helsinki): as the first Minister of Defence of Finland and briefly the Commander in Chief of the Finnish army, Thesleff was the first Commander-in-Chief of the Suojeluskuntas. Thesleff began his military career in 1894 at the Hamina Cadet School from which he graduated in 1901. He continued his military studies in St Petersburg at the Nikolai General Staff Academy over the years 1904-1907 and the the Officers Cavalry School from 1910-1911. He was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, 12 June 1912. Thesleff fought in the first world war in the Russian army (1914-1917), until he was captured by the German’s in Riga in September 1917. In October 1917 he was transferred due to a request from the Military Committee to serve as a liaison officer between the Finnish Jäger battalion fighting under German command and the Germans.

Georg D. von Essen: Commander-in-Chief of the Sk organization

He deposed the unpopular Colonel Nikolai Mexmontan. He was the commander of the Finnish Jäger Battalion 27 from 6 November 1917 until 25 February 1918. In March 1918 he was appointed as a liaison officer with the German Baltic Division during the Finnish Civil War. After the Finnish Civil War Thesleff became the War Minister (from 27 May 1918 – 27 November 1918) in the first cabinet of Juho Kusti Paasikivi. He was promoted to the rank of Major General on 14 June 1918. After the resignation of Major General Wilkma, as War Minister, Thesleff became Commander in Chief of the Finnish military forces from 13 August 1918. The first Paasikivi Cabinet had leant towards Imperial Germany but after Germany was defeated in the First World War the cabinet resigned. This also meant the end of Thesleff’s political career.

However, in 1919, the Suojeluskunta became an independent organization within the Finnish defense structure, with its own independent HQ (initially named the “Suojeluskunta Toimisto” but in April 1919 renamed “Suojeluskuntain Yliesikunta,” commonly abbreviated to Sk.Y). Initially the HQ had only two sections, Military and Financial. Georg D. von Essen was elected as the first leader of the Suojeluskunta HQ and later (in 1919) to the position of Commander-in-Chief of the now independent Sk organization (a position he held until 1921, when General Kaarlo Malmberg took over).

The Command Structure of the Suojeluskuntas

- Suojeluskuntain Yliesikunta (Sk.Y = Sk General Headquarters): The high command of the Suojeluskunta, headed by the Commander-in-Chief of the Suojeluskunta. When the Sk.Y was first established in 1919 it had two departments, in less than a year the number had increased to seven.

- Suojeluskunta Piiri (Suojeluskunta Districts): Each District controlled a number of Local Suojeluskunta Areas (usually two to three). Each district had a small District HQ lead by the District Chief (Piiripäällikkö). Most of the time Sk District HQs had 4 members and 2 alternate members.

- Suojeluskunta Alue (Suojeluskunta Areas): Each Area contained one or more local Suojeluskunta Units and had a small Sk Area HQ.

- Local Suojeluskunta: The Suojeluskunta Unit for one municipality or town.

From 1921 to the end of WW2, General Kaarlo Malmberg held the position of Commander-in-Chief of the now independent Sk organization.

At the Local Unit Level, officers were generally ranked as follows, but ranks would vary with the size and structure of the actual Unit:

- Paikallispäällikkö = Local Chief

- Koulutuksen Valvoja (Kapteeni) = Training Supervisor (Captain)

- Osastonjohtaja (Ylikersantti) = Detachment Leader (Staff Sergeant)

- Osaston varajohtaja (Kersantti) = Deputy Detachment Leader (Sergeant)

- Poik.urheilujohtaja = Boy Sport Leader

- Joukkueenjohtaja = Platoon Leader

- Ryhmänjohtaja = Squad Leader

- Ryhmän varajohtaja = Deputy Squad Leader

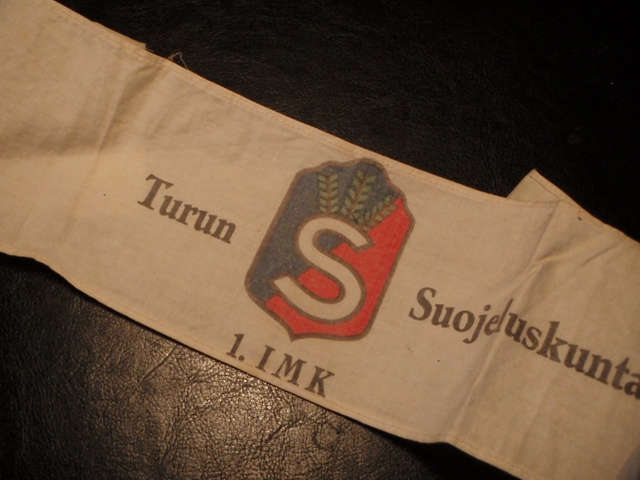

By 1920 about 93 % of Finnish municipalities and towns had local Suojeluskunta Units. Local Units were generally identified by Arm Sleeve bands unique to each unit as per the example below:

Arm sleeve from the 1920’s from the local Suojeluskunta unit of the town of Forssa

Arm sleeve from the 1920’s from the local Suojeluskunta unit of the town of Turku

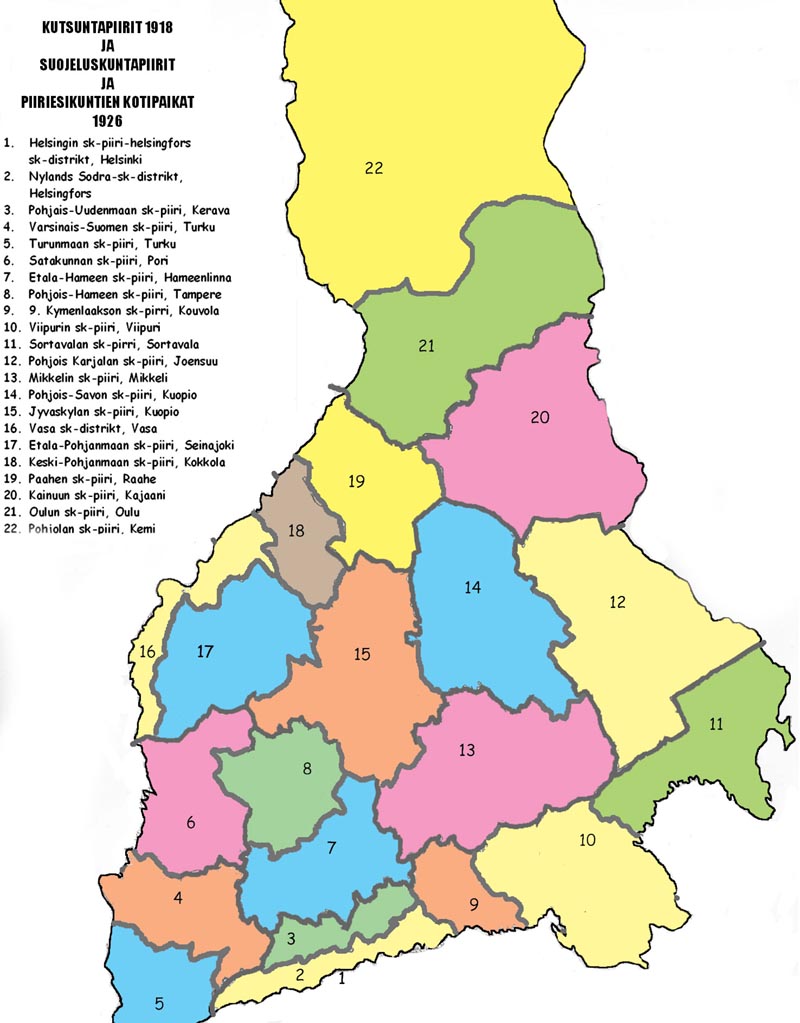

Suojeluskunta Districts

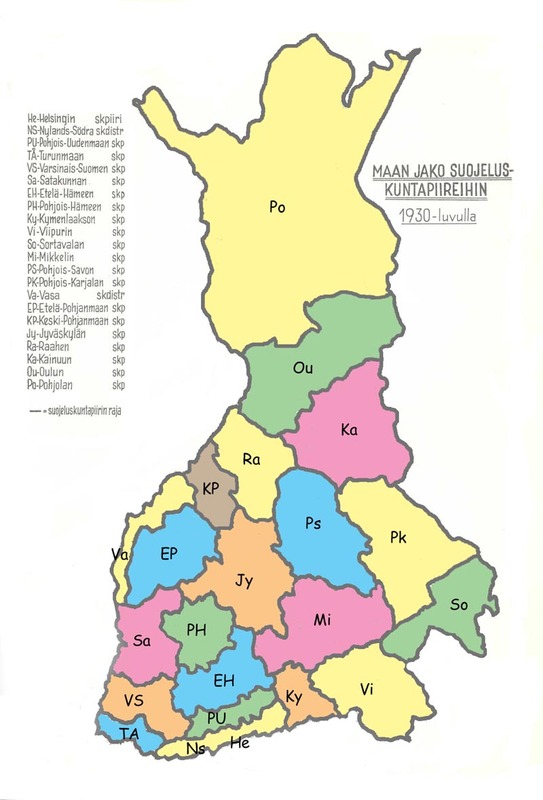

Each area of Finland was broken down into Suojeluskunta Districts. This section provides maps showing the location of the various districts and how these changed over time.

Suojeluskunta District Map 1918-1926

Suojeluskuntas District Map 1930

Selection of Suojeluskunta officials

The Finnish President selected and appointed the Commander-in-Chief of the Sk organization, but the Commander-in-Chief also had to be approved by Sk organization delegates before selection. Meetings of delegates consisted to 2 elected delegates from each Sk District and a Meeting could be called by the Suojeluskunta Chief-of-Staff or by five Sk Districts by written request.

The Suojeluskunta Commander-in-Chief appointed the Chief of each Sk District but before the District Chief was appointed, he also needed to be approved by the Sk District HQ of the Sk District he was about to lead. District HQ members were selected for a two year period and were elected by Representatives of Local Area Suojeluskuntas within each Sk District in annual meetings held in February. In these annual Sk District meetings each Local Area Sk within the Sk District had 1 – 3 representatives depending on the size of the local Suojeluskunta. Additional Sk District meetings could be called by the District Chief and by the Sk District HQ.

Each Local Area Suojeluskunta HQ was lead by the Local Chief (Paikallispäällikkö), who headed the local Suojeluskunta HQ, which had 4 members and 2 alternate members. Members of these Local Area HQs were elected for a period of one year in general annual meeting held in January.

Selection of Sk. Members

Sk members were divided to two categories: Actual members and Supportive members. Supportive members paid the membership fee, but didn’t have the right to vote in Suojeluskunta elections, had no right to wear Sk uniforms and had no responsibility for attending Suojeluskunta training.

The information below concerns only Actual members:

The conduct demanded from those willing to become Suojeluskunta members was quite clear: They had to be trustworthy Finnish males of at least 17 years of age (those willing to join but who were under 21 needed permission from their legal guardian). To be more precise, in this case being trustworthy meant not having a criminal past or the “wrong” kind of political ideals. Ex Red Guard members from the Civil War never had any chance of joining and neither did Communists (who were basically seen as the enemy). As a rule Social Democrats (the moderate left) were also unwanted until the previously mentioned reconciliation between the Social Democratic Party and the Suojeluskunta organization in 1930. The existing members (especially the Chief of the Local Suojeluskunta) decided who was considered trustworthy and who was not. If members of the Local Sk organisation weren’t familiar with the applicant, then written recommendations from two trustworthy persons were needed.

As mentioned in an earlier post, in 1930, in one of the more dramatic moments in Finland’s history, Marshal Mannerheim, working closely with Vaino Tanner, engineered a reconciliation between the Suojeluskunta organisation and the leading Finnish leftist political party, the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Together, in newspaper articles and in a number of joint speeches across Finland, they emphasized the need for a spirit of national unity and the dangers of the rising move towards totalitarianism in Europe. This affected opinions within both organizations and started a swing within the SDP towards a more positive opinion of Finland’s defense organisations and the need to increase military spending. Prior to this rapproachment, Sk members had not been welcome within the SDP, but after the “Reconciliation,” opinions on both sides had started to change.

Within the Suojeluskunta, the leadership encouraged members to take the first step in removing hostility between the SDP and the Sk-organization. A formal event welcoming both Social Democrats into the Suojeluskunta, and Sk-members into the SDP was held on the 15th of March 1930. The symbolic significance was large, but the actual results for members of both organizations were not immediately so. The symbolic significance was large, but the actual results for members of both organizations were not immediately large. By the 10th of April 1933, only about 1,000 Social Democrats had joined Sk organization. However, with Marshal Mannerheim, Vaino Tanner and other SDP politicians and party leaders working together to emphasis the need for Finland’s defences to be strengthened, and new financial incentives for Sk. training included within the State Budget from 1933 on, membership of the Sk began to grow significantly from 1934 on.

Suojeluskunta leaders and some (but by no means all) SDP leaders worked together to emphasis the need for Finland’s defences to be strengthened, and continually emphasized that the Suojeluskunta was a “Finnish” organisation, and not a “political” organisation. With SDP membership no longer being a bar to Suojeluskunta membership, and with the changes in military training that began to take place from 1931 on, membership of the Suojeluskunta began to grow significantly from 1931. An added encouragement was provided by the new financial incentives for Suojeluskunta training included within the State Budget from 1931 on, as well as the support offered by both state-owned and private businesses for Suojeluskunta membership. While there was still Union opposition, it became ever more muted over time as more and more Union members joined.

The growth in numbers of “Active” Suojeluskunta members from 1930 – 1939 was indicative of the success of the “Reconciliation”:

1931: 88,700

1932: 89,700

1933: 101,200

1934: 109,500

1935: 126,700

1936: 152,500

1937: 161,900

1938: 201,000

1939: 276,300

The large surge in membership in 1936 coincided with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War whilst the additional large membership surge in 1938 concided with the Munich Crisis and the now obviously looming threat of another European War. These were the active members capable of military service in the event of war. In addition, there were the “Veteran” members, those who were classified as too old for active military service or who worked in a wartime-critical job and who were refused permission to leave their jobs but who kept up their training and who were grouped into “Home Guard” units. There were some 55,000 men in this category, grouped into Battalion-strength units and organised under the Home Guard Command structure.

OTL/ATL Note: In reality, the reconciliation didn’t occur until 1940, after the Winter War, and while Sk. Membership in 1930 was the 88,700 given, in 1939 Sk. membership was 119,500 rather than the 276,300 given. This is significant as the Sk. Membership were the core of the Reservist Army, providing the bulk of the Reserve Officers and NCO’s as well as a substantial number of trained soldiers who carried out active training throughout the year. In this ATL scenario, the number of such soldiers has effectively more than doubled, and as we will see when we come to the changes in military training that took place through the 1930’s, there are further changes that result in a much larger number of non-Sk Reservists receiving annual “refresher” training. The end result, as we will see, is a larger, highly-trained and well-equipped Reserve Force available at the start of the Winter War.

Suojeluskunta Boy Unit Member

After 1920, Suojeluskunta members who were at least 20 years old had one vote in the elections of his Local Suojeluskunta and until the statute of January 1934 could also be selected for a responsible position in his Suojeluskunta. After the Statute of January 1934, Suojeluskunta members got one vote in the Suojeluskunta elections after belonging to the Suojeluskunta for one year. As kind of a “old member bonus”, they could also get another vote. This “old member bonus” vote was available to those who had belonged to Sk for 15 years, or were over 40 years of age and had belonged to the Sk for at least 10 years. The statute also required those selected for responsible positions to be at least 21 years of age.

Those wanting to join, but younger then 17 could join Boy Units (Poikayksikkö). In the 1920’s, these Suojeluskunta Boy Units didn’t give military or weapons training, but instead concentrated on sports. The First Boy Units had been the so called “Squirrel Companies” organized soon after the Civil War for 13 – 16 year old boys wanting to join the Suojeluskunta . In that first try sports alone proved too little to maintain interest, but later in the 1920s interest reappeared and this time it proved more long lasting with a resurgent Suojeluskunta Boy Units ecoming active from 1928. Boy Units also worked to aid recruiting of new members to Sk. Once members of Suojeluskunta Boy Units reached the age of 17, they were transferred from Boy Units to the ordinary Suojeluskunta units. Sports and other activities of the Boy Units attracted many boys to join and about 70 % of them moved on to join the regular Suojeluskunta after reaching the required age. In 1939, the Boy Units had a membership of approxinmately 200,000, a substansive percentage of Finland’s teenage males under the age of 17.

The Suojeluskunta Oath

The Suojeluskunta Oath for active Sk-members before the Suojeluskunta Law of 1927:

“Minä N.N lupaan ja vakuutan kaiken sen kautta, mikä minulle on pyhää ja kallista, että tulen rehellisesti toimimaan Suojeluskuntien tarkoitusperien, Suomen puolustuksen ja laillisen yhteiskuntajärjestyksen turvaamisen edistämiseksi sekä ehdottomasti alistumaan esimiesteni määräyksiin sekä etten vastoin esikunnan suostumusta eroa Suojeluskunnasta, ennenkuin kuukausi on kulunut siitä, kun olen esikunnalle ilmoittanut haluavani Suojeluskunnasta erota.”

“I (first-name surname) will promise and declare by all that is holy and dear to me, that I will sincerely act to promote the goals of the Suojeluskunta, Finnish Defence and the securing of the legal social order and that I will absolutely submit to the orders of my superiors and that I will not resign from the Suojeluskunta without the permission of HQ, or until one month has passed from me informing HQ about my wish to resign.”

The Suojeluskunta-Oath for active Sk-members after the Suojeluskunta Law of 1927:

“Minä N.N lupaan ja vakuutan kaiken sen kautta, mikä minulle on pyhää ja kallista, että Suojeluskunnan varsinaisena jäsenenä rauhan ja sodan aikana rehellisesti toimin isänmaan ja laillisen yhteiskuntajärjestyksen puolustukseksi, alistun sotilaalliseen järjestykseen ja kuriin sekä täytän minulle kuuluvat velvollisuudet ja annetut tehtävät”.

“I (first name surname) promise and declare by all that is holy and dear to me, that during peace and war as an active member of the Suojeluskunta I will act sincerely for the defence of the fatherland and the legal social order, I will submit to regimentation and military dicipline and will fulfill the duties and tasks assigned to me.”

Main functions of the Suojeluskunta during peace

Suojeluskunta Choir

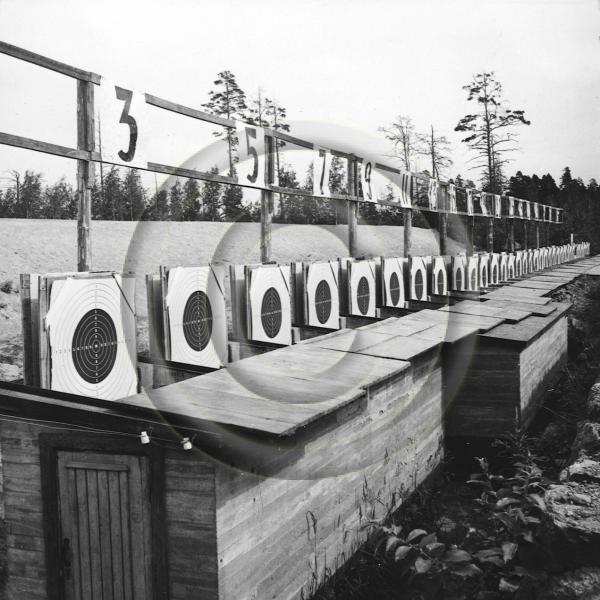

The primary functions of the Suojeluskunta were defined as “Giving military training to its members” and “Assisting Finnish Armed Forces when needed.” In the 1920s local Suojeluskuntas in the border areas were also often used to assist with border patrol and protection duties as there were far too few Frontier Guard units to adequately patrol Finland’s lengthy borders with the Soviet Union. Additional functions of the Suojeluskunta were defined as:

- Supporting athletics and sports

- Assisting authorities when asked (Police Officials & the Government in general)

- Propaganda (Publicity)

- Suojeluskuntas were very active in supporting athletics and sports

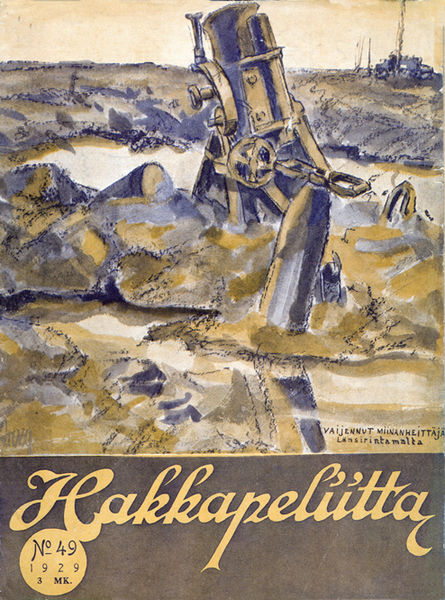

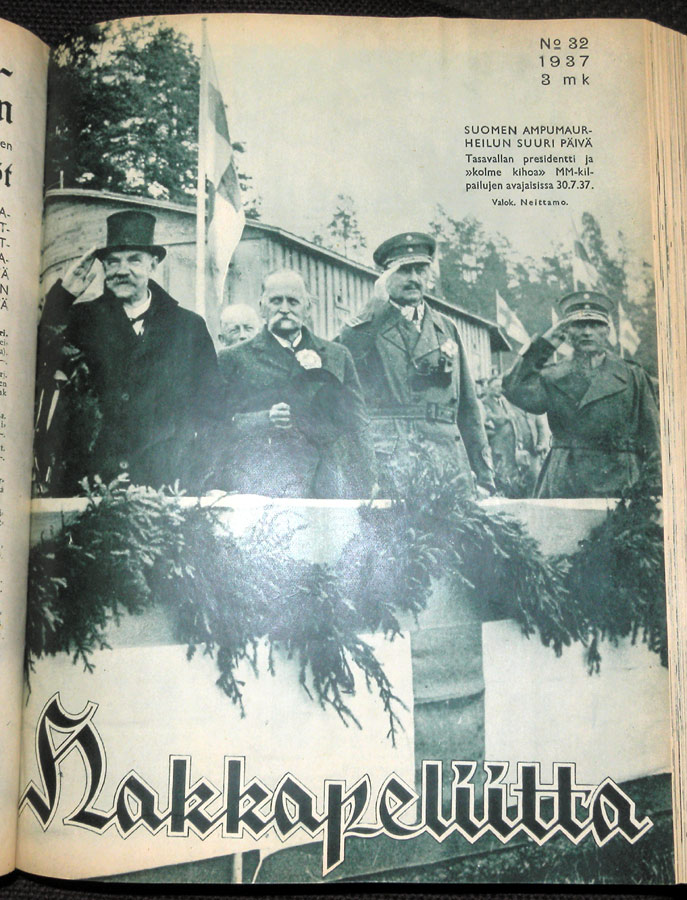

Aikakauslehti Hakkapeliitta 49/1929, kansikuva. Kannen tekijä tuntematon

Assisting authorities in a wide variety of situations where organized and armed troops might be included: This included missions like searching large areas, guard duty and assisting in the apprehension of dangerous criminals. The Finnish Prohibition from 1919 – 1932 resulted in many requests to provide assistance to the authorities as searching for illegal stills hidden in forests demanded a lot of manpower. Some Suojeluskuntas were enthusiastic about destroying illegal stills even without the authorities asking them, while other units were less inclined to provide assistance.

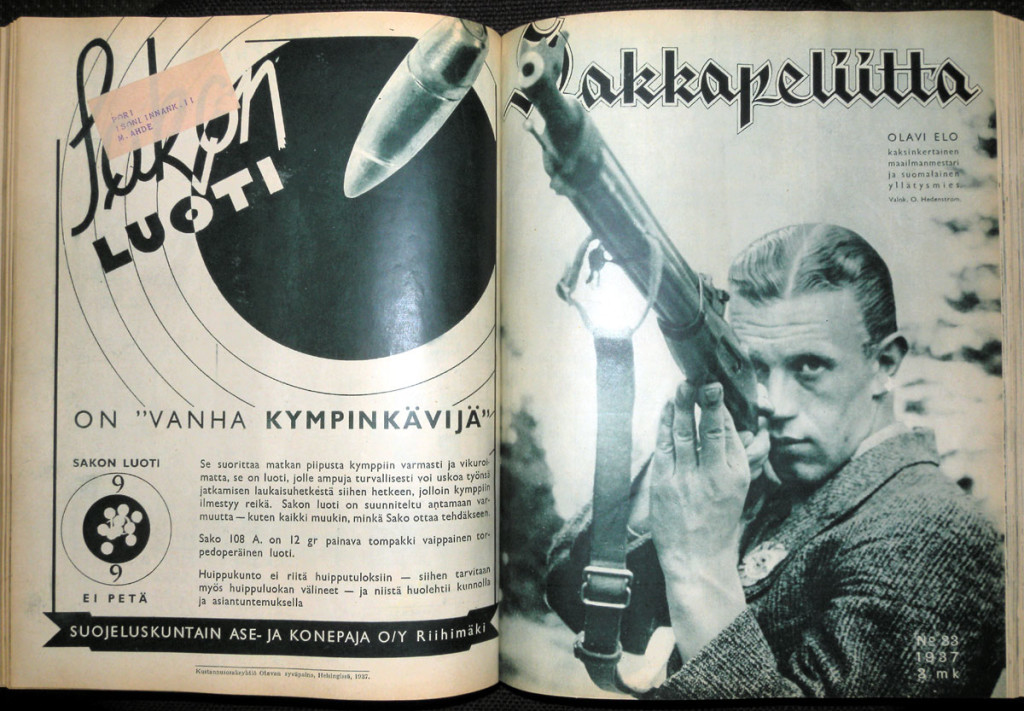

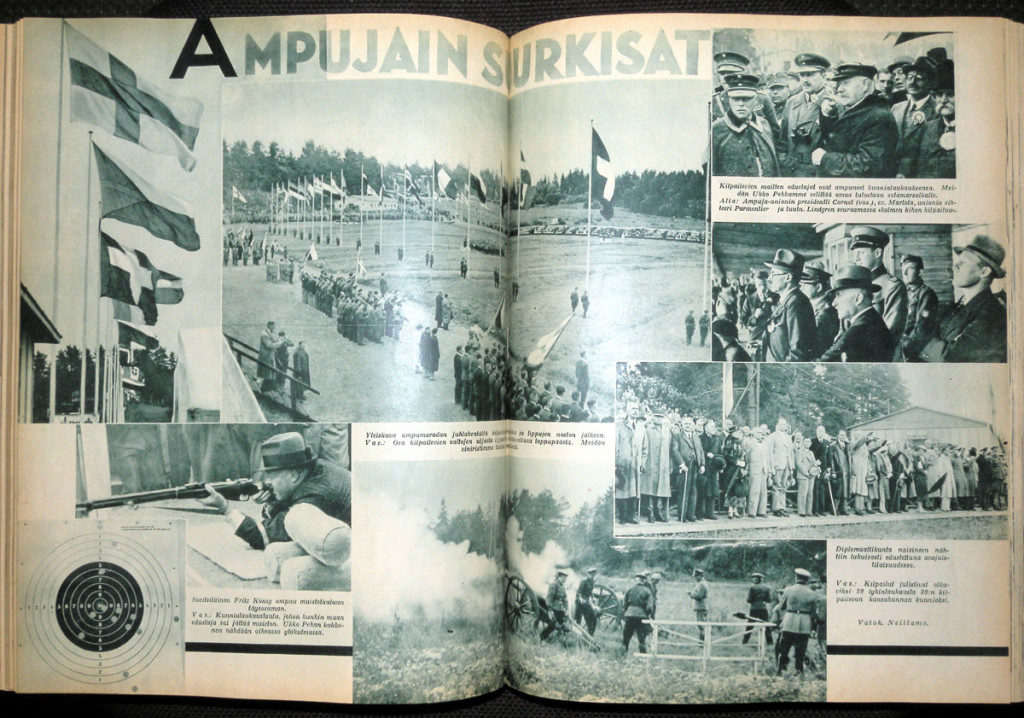

Propaganda: Publicity created by Sk organizations was typically quite subtle. Instead of derogatory and chauvinist speeches, Sk publicity favored organizing popular events using sports, choirs and orchestras as attractions and included some patriotic parts (music, poems etc.) in the programme. Suojeluskuntas also had their own their magazine: “Suojeluskuntalaisten Lehti” (“Magazine of Sk-Members”) published by “Kustannusosakeyhtiö Suunta” (“Publishing-Ltd Suunta”), which was replaced with the Sk-organization published “Hakkapeliitta” in 1925. From 1926 on, “Hakkapeliitta” was a weekly color magazine with tens of thousands of subscribers. However, it wasn’t the only such publication. “Suomen Sotilas” (“Finnish Soldier”) was also a popular magazine and many Sk-Districts had their own magazines. The fact that the large majority of opinion leaders in Finland in the 1920s and 1930s such as teachers and priests, had a positive attitude towards the Sk-organization didn’t do any harm either.

As we will see, from the early 1930’s on, the Sk-organisation worked increasingly closely with the military to produce short Films and “News” clips promoting the military and the Suojeluskuntas (from the mid-1930’s on, these were generally shown in Cinemas before the main feature and were rather well-done) as well as Training Movies and Training Pamphlets and advertising campaigns promoting various aspects of the military and the Suojeluskuntas. An excellent example of this was the campaign supporting the Government’s initiative in introducing School Dental Nurses which simultaneously extolled the role of the Army in bringing the need to the attention of the Government. Another such campaign was that supporting the introduction of “School Meals”, again both supporting the Government initiative, again extolling the role of the Army in bringing the need to the attention of the Government and praising the Lotta Svard organisation for their voluntary work in implementing and running the program for the benefit of all Finnish children. Such campaigns served to more and more create a favorable impression of the Suojeluskunta and Lotta Svard organizations across the entire political spectrum.

Suojeluskunta Finances

The Sk organization and its units were financed from four main sources:

- Voluntary funding: These included donations, membership fees and money collected by Suojeluskunta and Lotta Svärd organizations as entrance fees to functions they had organized and so on. This was the largest source of funding for local Suojeluskuntas.

- Funding from the State Budget: This started when the Finnish State decided to pay the wages of some hired personnel of the Suojeluskunta organization. The sums increased as the Sk organization grew larger, but the Suojeluskunta always remained an inexpensive tool for helping to maintain the defense capability of the Finnish State. State Funding for the Sk at all times remained less than 2% of the yearly State Budget and less then 12% of overall defense spending.

- Funding from Municipalities, Towns and Cities: These typically financed local Suojeluskunta units (as long as left wing parties didn’t have a majority on the local council). From 1930 on, almost all local Suojeluskunta units received Municipal / Town funding.

- Business profits from firms owned by Suojeluskunta: Three parts of the Suojeluskunta-organisation were organized as independent companies from early 1927 and also did business outside the Suojeluskunta-organization, functioning for all intents and purposes as commercial entities (which in fact they were).

These organizations were:

- Suojeluskuntain Ase ja Konepaja Oy (SAKO = Weapons and Machine Factory of Suojeluskunta).

- Suojeluskuntain Kauppa Oy (SKOHA = Shop of Suojeluskunta).

- Suojeluskuntain Kustannus Oy (= Publishing House of Suojeluskunta).

Suojelusjunta Band

For fundraising, the chapters organised numerous informal events and lotteries. It is estimated that about one fifth of all get-togethers in Finland in the 1920’s were organised by the Suojeluskunta and as many again by the Lotta Svärd – and by the end of the 1930’s, the figure was probably twice this, meaning the Suojeluskuntas / Lotta Svärd organizations were a key component within Finland’s social fabric. To this end, the Suojeluskunta chapters had several hundred choirs, orchestras, and theatre groups as well as numerous buildings that served a dual function as Armouries, Drill Halls and Social Venues (indeed, if you were a Suojeluskunta member, as often as not your wedding reception took place in a Suojeluskunta Hall).

A typical Suojeluskunta Local Unit Hall in a rural area….constructed by volunteers and using donated lumber

With the ongoing reorganization and restructuring of the Finnish Armed Forces from 1931 on, the Suojeluskunta-organisation came to play an important role in various aspects of defence and was allocated either increased funding or direct support from the military as the organisation came to assume these roles. In addition, the Defence Ministry in some cases contracted direct to the Suojeluskunta businesses – for example, purchasing weapons from SAKO and contracting out the making of training films and pamphlets to Suojeluskuntain Kustannus Oy (something we will look at in more detail in a later Post). These activities all resulted in increased indirect funding for the Sk.

Overall, the financial costs of the Suojeluskunta were minimal when compared to the contribution the organisation made to Finland’s Defence. All the training carried out by Suojeluskunta members was voluntary, most local units built their own Unit Halls with voluntary labour and donated materials and into the 1930’s, members and local units paid the costs of weapons and ammunition.

III – Suojeluskunta Training in the 1920’s

Training in the Suojeluskuntas did not start well. After the Civil War, the Armed Forces picked the best trained and most competent Officers and NCO’s. Meanwhile the Sk organizations had trouble hiring capable Officers and NCOs. The low quality and inexperience of the Sk Officials responsible for training manifested itself in low quality training throughout the whole Sk. organization. In December 1918 the leadership of the Suojeluskunta decided that the Sk. organization as a whole needed its own Officer School.

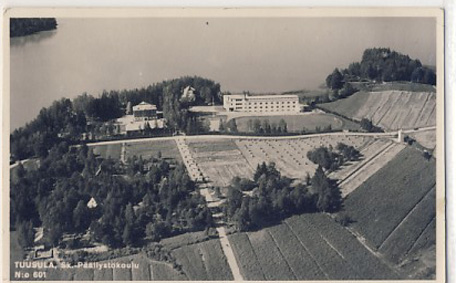

Hämeenlinna Päällystökoulu (Civil Guard Officers School)

The Officer School (“Päällystökoulu” aka “Sk.Pk”) was established in 1919 in the town of Hämeenlinna and the first course for Sk Officers was held in there in October 1919. A few Sk Districts also organized their own courses for Sk Officers, and from 1921 some Sk Officers also started being trained at the Kadettikoulu (the Officer Cadet School of the Armed Forces), although the number of Sk officers trained through the Kadettikoulu proved minuscule compared to those trained by the Sk Officer Schools (some 1,100 Officer-trainees over the first three years). Over the course of the 1920’s, several new buildings were added to the School and the training given progressively improved and diversified.

One of the key factors in improving the situation through the 1920s was that starting from 1921, professional soldiers (primarily Officers from the Finnish Army) replaced the highly-motivated but less professionally-skilled nationalists and independence activists who made up the initial training cadre. Generally speaking, those Conscripts who were selected for Reserve Office Training received basic junior-level Officer Training while completing their conscript service. A very very small number of these Reserve Officers then went on to enter the Cadre Army as full-time Officers, where they went through the Kadettikoulu (the Officer Cadet School of the Armed Forces) training (touched on in an earlier post). Of the remaining Reserve Officers, many went on to join the Suojeluskunta – from 1931 on this was an expectation that was almost always fulfilled – and it was within the structure of the Suojeluskunta training program that these Reserve Officers received the bulk of their more advanced Officer Training. Junior Officer Training at this time (the 1930’s) was very tough and very professional, with the curriculum content constantly being updated and revised based on experience from exercises and from Officers attached to foreign armed forces from 1931 on (a program initiated by Marshal Mannerheim).

The Content of Sk Officer Training in the 1920’s

Officer Candidates from the Suojeluskunta Officers School participating in a Field Exercise in June 1934.

The educational standard required of Sk Officers was confirmed in May of 1921. The level of education and basic training required for Sk Offices was set as being at least 5 years of secondary school or equivalent schooling, together with Sk Officer courses and passing the Sk Officers Exam. And having met these requirements didn’t necessarily guarantee promotion. In 1923 the courses and studies for Sk-Officers were also standardized. The Course of Study included much theoretical and doctrinal knowledge, so reading and studying the listed books from the curriculum was an important part of preparation. The subjects studied by Sk Officers included:

- Military Forces doctrine

- Suojeluskunta doctrine

- Weapons doctrine

- Terrain doctrine

- Fortification doctrine

- Tactics

- Company tactics

- Machinegun tactics

- Artillery tactics

- Horse management

Subsequent to the Military Review of 1931 ordered by Mannerheim, a number of other subjects were progressively added to the curriculum over the course of the 1930’s. These included (among other subjects):

- Armour doctrine

- Close Air Support doctrine

- Anti-Aircraft doctrine

- Anti-Tank doctrine

- Inter-arms coordination

If mobilization had taken place in the 1920s, Sk Officers would have been ordered to fill the ranks within the Army for which they had received training when they had carried out their Conscript Service in the military. This was a clear organizational weakness and would have been a waste of resources – this was recognized in the Military Review of 1931 ordered by Mannerheim and was addressed in the subsequent military reforms of the early to mid 1930’s, as we will see.

In 1933, as one of the many reforms of the military being undertaken, the Suojeluskunta created a separate Sk NCO School. Prior to 1930, Sk NCO’s had generally received Junior NCO training during their Conscript Service and on joining the Sk, were generally assessed and appointed to NCO positions after having been a member for some time and having proved their worth within the organisation. The Sk NCO School was created to provide Sk NCO’s with both Senior NCO training (for Sergeants, CSM’s, Warrant Officers) and to provide NCO’s with the training to allow them to fill positions that would in the past have been held by Junior Officers. The objective was to ensure NCO’s were capable of stepping up in the event that Unit Officers were killed or incapacitated during combat.

Sk Member Training Requirements in the 1920’s

Early Suojeluskunta Training Session in a Local Unit Hall