The Finnish Army of the 1920’s – Part I

And at the start, an acknowledgement: substantial parts of this particular page on the Finnish Army of the 1920’s are not original and were taken from a thread on the Paradox Gaming Forum by Karelian about the lead up to the Winter War. With Karelian’s permission, I’ve reused them for my own alternate history – a kindness that I gratefully acknowledge.

When the victorious Government that emerged from the Finnish Civil War begun to organize a new national army in 1918, this new force drew much inspiration from the previous Finnish national army that was, paradoxically, much older than Finnish independence. Previous to being ruled by Russian, Finland had been under Swedish rule for centuries and as far back as the Thirty Years War, Finnish Regiments had been recruited into the Swedish Army. By 1636 for example, the Wunsch, Wrangel and Ekholt Cavalry Regiments and the Vyborg, Wrangel, Essen, Grass, Horn and Burtz Infantry Regiments were Finnish unit serving under the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus in his campaigns in Germany. When Charles XII set out in 1700 to enlarge his Empire, the Finnish Rehbinder Cavalry, Knorring Dragooons and Tiesenhausen, Lode and Gyllenstrom Infantry Regiments were part of his Army.However, in the decisive Battle of Poltava, Russia’s Peter the Great had destroyed Charles XII Army, the Finnish Regiments were decimated and Finland was temporarily overrun by Russia in 1713 (and in the overrunning, Finland’s population decreased from 400,000 to 300,000 – and not from natural causes).

In 1788, the King Gustav III had taken advantage of Russia’s war with Turkey to march on St Petersburg. Afraid their country would be partitioned between the two protagonists, some Finnish Officers formed the Anjala League to promote separation from Sweden and the formation of an independent Finland under Russian protection. Gustav III’s execution of some of these Officers resulted in his assassination, ending the war. Although Finland was little affected by Gustav III’s war, disaster accompanied the war of Gustav IV. The Swedish Army, whose troops at this stage were mainly Finnish, withdrew under the orders of their Swedish Generals, were defeated and in 1809 Finland was declared to be part of the Russian Empire as a Grand Duchy. The Finnish Regiments, trained in Swedish military techniques, were disbanded. However, the war against Napoleon led the Tsar to allow Finnish volunteers to form three Regiments in 1812.

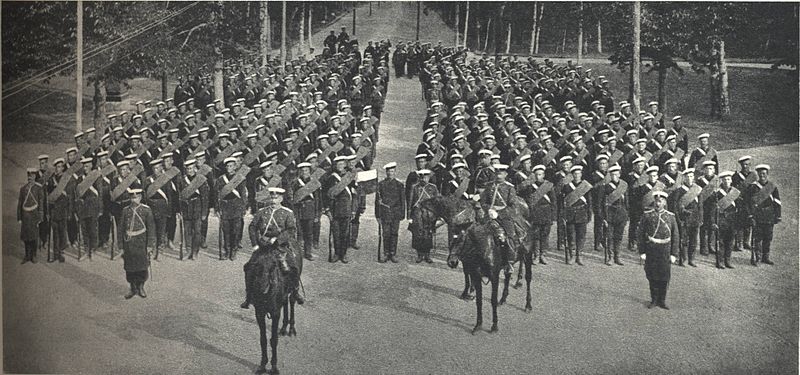

Vaasa sharpshooter battalion (1901) (Suomen Vaasan Tarkkaampujapataljoona)

Throughout the succeeding century, the strength of the Finnish Armed Forces had fluctuated with the diplomatic situation. Within the Russian Army, 8 Finnish Regiments and 3 Jaeger Battalions were maintained. Finnish troops took part in crushing the Polish Uprising in 1830-31 and in the Russo-Turkish War if 1877-78. Although the Russian Army was responsible for Finland’s defence, a general conscription law passed in 1878 had provided for a force of 6,000 men for local defence. Rifle Battalions had been formed in 1881 to carry out the training specified by the new law. Reserves were trained within local companies. By 1900, Finland had it’s own Army of 8 provincial (sharpshooter) battalions, a Regiment of Dragoons (made up of six squadrons of cavalry) and the Finnish Guard, all commanded by a Governor-General answering to the Tsar. Each military province had 4 Reserve Companies. The Finnish Army of that period was lightly equipped with no heavy weapons or Artillery. In training, the main focus was on accurate rifle shooting and there was also some emphasis on irregular tactics, based on Russian Army training.

However, following the uprisings throughout the Russian Empire after the fiasco of the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, the Tsar had begun a policy of Russification in Finland and the last units of the Army of the Grand Duchy of Finland were decommissioned (also in 1905). Many Finns however either continued, or went on to serve, in the Tsarist Russian Armed Forces. Mannerheim was one of these and many of the former officers who had trained in the (originally Swedish) military academy of the Hamina Cadet School started a new career as the first commanders of the new Finnish Army. These men were still firmly in charge in the General Staff when the outlines of the new Finnish Army of were being drawn.

Following the successful conclusion of the Finnish Civil War (in which, incidentally, Mannerheim had strongly opposed an agreement reached between the Finnish Government and the Germans to send a German Expeditionary Force to assist the Finns, believing the White Forces were strong enough to defeat the Reds without German help – a position which he was later able to parley into support from the victorious Allies and diplomatic recognition for the new State in May 1919) Mannerheim had resigned in May 1918, disapproving of the inordinate influence of the Germans and the German-trained Finnish Officers in the organization of the Finnish Army.

After the Civil War ended, the Suojeluskunta were officially turned back into a semi-independent paramilitary organization in February 1919. While the leadership of the Suojeluskunta movement wanted to regain their freedom to operate and develop their organization as they saw fit, the newly formed Finnish Army (Maavoimat) was seeking a way to become a truly national army for the war-torn nation – a force based on the other side of the Civil War would have surely been unable to win over any respect from the supporters of the Reds. Army leaders aimed to turn the military into a guardian of a new national consensus, and carefully sought to keep it away from daily politics while turning the conscription system into a way of indoctrinating new age-classes of conscripts into reliable citizen-soldiers of the young Republic. In September 1919, in the middle of the turbulent years of the Heimosodat (the Kinship Wars that we have covered earlier), the legal framework for the Army was finally ready.

The highest authority was reserved to the President of the Republic as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, with the Chief of Staff and the Head of the Army both under his command, controlled by the new War Ministry. In 1922 (after the threat of getting involved to the Russian Civil War was removed and Treaty of Tartu was signed) the legal framework was expanded further when a new Conscription Act made military service compulsory for every able-bodied adult male, starting from the age of 18 and releasing the reservists from the last reserve category at the age of 65. The basis for the new conscription system was a cadre system. A small professional core group of Officers and NCO’s and a small standing Army would train reservists, who would remain in training for a period that would generally last a year, with three months of additional extra service in the Air Force, Cavalry, Technical and Supply units. The new system drew it’s inspiration from pre-war Russian methods due to the influence of the Russian-trained General Staff Officers, but some parts of the system were also copied from Germany due the insistence of influential Jaeger officers.

This reform was the first time (but certainly not the last) when internal conflicts between the two different schools that would determine the status and development of the Army during the 1920s emerged: The disagreements over methods between German-trained Jaegers and the Russian-trained “Old Guard” on the one hand, and between the Army and Suojeluskunta on the other would continue. However, one area that was agreed on quickly was Mobilization. This was a problem for Finland as the country was both large and sparsely populated, with considerable time required to mobilize and concentrate the Reserves. With the Soviet Union on the other side of the border, it was imperative that mobilization occur rapidly. The Cadre mobilization system was used in the Finnish army from April of 1918 to April of 1934. Just as in later mobilization systems, the whole country was divided into military districts and upon mobilization a certain number of units would be formed in each of these districts. In this system (based on the German mobilization system) each of the wartime Army Regiments had an active peacetime battalion-sized unit as a cadre, around which the wartime unit ,when mobilized, would be formed by filling up the ranks with reservists. The first ambitious mobilization plan made in 1918 would have required forming 9 divisions (with a total of 27 infantry regiments), but at that time Finland didn’t even have half of the needed trained troops or weapons for an the Army of that size.

Training of recruits through the 1920’s followed a similar pattern to other European countries. The Finnish Army was largely infantry based and conscripts were taught the basic infantry skills – drill, discipline, shooting, fitness and small unit tactics with an emphasis on the tactical skills being developed for Finnish conditions.

The plan was revised somewhat in 1919, being based on a more realistic 3 Infantry Divisions, a Jaeger Brigade and other units. As more conscripts went through training and the trained Reserves grew in strength, the planned size of the Army on mobilization grew steadily year by year. In 1921 the mobilization force was re-set to 6 divisions and 1 Jaeger Brigade, but the Finnish military had come to the conclusion that 10 Divisions would be needed to adequately fight a defensive war. In 1927 Finland finally had the trained reserves to form 7 Divisions on mobilization, but the Defense Revision of that time suggested a future wartime Army of 13 Divisions would be needed. The constantly growing size of the mobilized Army meant that more equipment was constantly needed, and through the 1920’s there was a constant race between the ability of the Army to provide arms and equipment with a very limited budget, and the growing numbers of trained reserves to whom equipment would need to be issued on mobilization.

To a certain extent the Army managed this situation by limiting the number of Conscripts to be trained through stringent medical exams, eliminating many who might have been trained (a situation that was to be rectified in the 1930’s). This meant that a balance between equipment and trained reserves was maintained, but it also meant the number of trained reserves was less than it might have been. The budgetary battles also meant there was very little expenditure available for anything other than basic military equipment. Weapons used by the Finnish Army were largely those left over from the Civil War or inherited from the Russians and the Germans. The Russian Mosin-Nagant M/1891 was the principal Rifle, the Maxim M.1909 was the principal Machinegun.

The old Mosin-Nagant

While the old Mosin-Nagant remained in production in the Soviet Union as it was, Finns took this battle-proven weapon as the starting point and, in the 1920’s, reverse-engineered it to produce a new family of more accurate and reliable service rifles.

OTL Note: The Russian Mosin-Nagant M/1891 was a manually operated bolt-action, magazine fed rifle. It fired 7.62 mm ammunition, fed from an integral, single stack magazine, loaded from clip chargers, with a capacity of 5 rounds. The Mosin-Nagant had a maximum range of around three kilometers but was only capable of effective aimed fire out to ranges of 400-500 meters. The rifle is striker-fired, and the striker was cocked on the bolt open action. The positive aspects of the Mosin rifles were the reliability and simplicity of both manufacture and service.

Recruits being trained on the Mosin-Nagant Rifle (reused from KevOS4 with permission)

They were reasonably effective infantry weapons. Fairly good shooting can be done with them at combat ranges, although their sights do not lend themselves to fine degrees of accuracy. On the other side, this rifle had some serious drawbacks. The length made the rifle awkward to maneuver and carry, especially in woods and trenches. The horizontal bolt handle was short by necessity, so, in the case of the cartridge case being stuck in the chamber, a lot of strength was required to extract it. They suffered from an over-complicated bolt, but in other respects were relatively simple to service and maintain. The safety, in that it was extremely hard to engage and disengage, represented a major shortcoming of the weapon.

Advanced Recruit Training – out on Summer Maneuvers with Mosin-Nagants

The Mosin-Nagant rifle was developed in the late 1880s and early 1890s, and was officially adopted for service by the Russians in 1891. During the official trials, two designs were selected – one by a designer from the Tula arsenal – Mosin – and another by the Belgian brothers Emil and Leon Nagant. The final design, adopted by the Commission utilized features from both. The action of the rifle was developed by Colonel S.I. Mosin, and the magazine was developed by the Nagants. Along with the rifle, a new, small-caliber cartridge was adopted. This cartridge had a rimmed, bottlenecked case and a jacketed, blunt nose bullet. The rimmed case design, which at that time had already started to became obsolescent, was largely driven by the low technical capabilities of the Russian arms industry. This decision kept this obsolete, rimmed cartridge in general service with Russian army for more than 110 years.

The Mosin-Nagant was one of the earliest small-caliber battle rifles developed in the late 19th century. Its rugged design and construction are borne out by the fact that the only changes ever made to its basic design were to shorten and lighten the rifle as ammunition improved and battle conditions changed. This venerable design is arguably the longest-lived and is also one of the most widely-produced and copied firearm in the world. This design saw action in almost every major conflict of the twentieth century, from WWI, the Russian Civil War, WWII, Korea, Vietnam, and even in Grenada. The standard North Korean and Chinese rifle of the Korean War was the Russian-designed Mosin-Nagant M1891/1930. The 1891/30 was found on many North Vietnamese during the Vietnam War. Thousands of these obsolete but deadly weapons were given to the Viet Minh and later to the Viet Cong. As the war continued, these were replaced with the AK-47 rifle. Up to 1943, Soviet infantry was primarily armed with the bolt-action 1891/1930 Mosin-Nagant rifle with iron sights. It was accurate to 400 meters. The scoped Mosin-Nagant sniper rifle was accurate to 800 meters. During WW2, the Soviet Union replaced the infantry Mosin-Nagant rifles with submachine guns.

Finnish Recruits training on the Mosin-Nagant

The Mosin-Nagant can be used as a sniper rifle if it is fitted with a telescopic sight. Sniper rifles, based on the M1891/30 rifles, were issued with scope mounts on the left side of the receiver and with bolt handles bent down. Red Army snipers hunted in pairs, one spotting and one firing. Both were armed with the Mosin-Nagant 1891/1930 rifle that fires a 7.62x54mm rimmed round. The rifle’s four-power scope mount also allowed the sniper to use the standard open sights for closer-in shots. The Mosin-Nagant rifle was in use for more than sixty years by half the world’s military forces. Developed in 1891, it was last manufactured in Hungary and China in the mid-1950s.

The Russian Maxim M.1909, the principal Machinegun of the Finnish Army of the 1920s, was another sound weapon that formed the core of the direct firepower of Finnish infantry units. Finnish usage of machineguns was directly copied from German methods and then adapted to local circumstances and terrain features. Fire from automatic infantry weapons was mainly provided by MGs. To maximize the effectiveness of these weapons Finnish prewar training manuals stated that they should; 1) have clear fields of fire, 2) be located in protective positions, 3) be positioned to give flanking fire (the goal being to catch the enemy in the crossfire of multiple MG’s) and 4) be able to cover any defensive obstacles (tank & infantry obstacles) with their fire. Importance of flanking fire was further emphasized by stating that “Flanking effect can be achieved by either fire, movement or a combination of both. A weaker force can hope to achieve success against numerically superiour opponent by attacking to the flanks. Flanking fire multiplies the effectiveness of fire, and when used together with tactical surprise and fire from other directions it has a paralyzing effect to the enemy, who is therefore forced to direct his attention and actions to multiple directions.*” (*Infantry Manual II, 1932)

The Maxim M/32-33

The Maxim M/32-33 was a Finnish modification of the old Great War MG from 1932. It had a faster rate of fire (up to 850 RPM vs roughly 600 of the original model), German-styled metallic ammunition belt and most importantly an improved cooling system with a snow hatch on the top of the barrel cooler. This little feature enabled the crews of the weapon to keep it operational and firing in winter conditions for extremely long periods of time if necessary.

The Maxims were gathered into special Heavy Machine Gun Companies in each Infantry Battalion. However, by the late 1920s, the analysis of earlier fighting in the Kinship Wars, the Civil War and the latest field exercises all clearly showed that the Maxim as a weapon was too heavy for successful mobile warfare in difficult forested terrain, where the limited visibility dictated that weapons had be located far forward, capable of delivering massive firepower while simultaneously remaining light enough to be quickly displaced when necessary. While suitable for static defensive warfare, a lighter and more mobile automatic weapon was needed. This was a demand that would only be addressed in the 1930s.

Finnish artillery of the 1920’s – 1877-vintage

Finnish Artillery was largely inherited from the Russians, with many older artillery pieces that were already semi-obsolete by the early 1920s. Due to budgetary constraints, these weapons were kept in service, although many, even in the 1920s, were used only for training. The only half-way modern artillery pieces in service were the Putilov M.02 76mm Field Guns, with a range of 11,000m and firing a 6.5kg shell, and the Schneider Mle.1913 105mm, with a range of 11,000m and firing a 15.9kg shell. Through the 1920’s and into the early 1930’s, the abysmal material condition, aged guns and chronic ammunition shortage of the Finnish artillery arm would haunt the Army. This would change through the 1930’s as the Finnish Army re-equipped with modern artillery, built up substantial ammunition stockpiles and trained using the pioneering methods of the Army’s Russian-trained artillery specialist General Nenonen.

Note: Artillery and Coastal Artillery will be addressed in more detail in a subsequent Post.

More Finnish artillery of the 1920’s

The new Finnish Army was founded upon old military traditions, drawing influence from Sweden, Russia and Germany. This mixing of different traditions and approaches caused internal friction within the new Army, but also ensured that there was an atmosphere where innovative new ideas could be freely discussed, as opposing camps of the Finnish military establishment were pitted against one another again and again during the defense policy debates of the postwar decades in the 1920s and 1930s. Studies of infantry tactics were a key part of the development of the Finnish military during the two decades between the Civil War and the Winter War. The developers of the first training manuals were men who had been trained by the German system, where competent NCO leadership emphasizing individual initaitive was encouraged, while their war experience was a unique mixture of the trench warfare on theEastern Front followed by the experiences of the Finnish Civil War and the Heimosodat (Kinship Wars) in Estonia, Ingria and Eastern Karelia. The fast-paced and relatively mobile (by WWI standards) small unit combat stressed the importance of rifle marksmanship, camouflage and most importantly the use of terrain. The ambushes, hit-and-run raids and constant maneuvers that had defined these conflicts were now taken to use in Army training schemes.

As noted before, the emphasis for flanking maneuvers and seizing the initiative were deemed important. And as paradoxical it may sound, the legacy of German-trained Jaeger officers ensured that tactical attack became the most favoured fighting style. While this may seem a suicidal tactic for a nation of 3.7 million bordering a superpower that was known to possess more trained reserves than the total population of Finland combined, it served the political mission of the Army rather well. As the emphasis in Finnish foreign policy was focusing on neutrality and the other Scandinavian and Baltic countries in the new era of “Red Earth”-coalitions of the SDP and the Agrarian League, the Army was seen more and more as the guarantee for the territorial neutrality of Finland in the event of a new European war. And since the peacetime army was in fact a mere delaying force with a primary mission of buying time for the mobilization of the field army (since the most expected scenario was that the enemy would launch a surprise attack), the ability to tactically harass and delay the advancing foe was deemed important.

The supply system of the Finnish Army was almost exclusively based on horse-drawn supply convoys

Furthermore, the majority of the the almost roadless Eastern Karelian border areas between Finland and the Soviet Union were considered to be terrain where division- or even regimental-sized formations would be unable to operate due the lack of the necessary infrastructure to supply them. (The supply system of the Finnish Army was almost exclusively based on horse-drawn supply convoys since mobility in roadless terrain was deemed vitally important – not that Finland in the 1920’s could have afforted even a modest motorization of it´s forces. Should mobilization of the Field Army be needed, the law forced the agrarian nation to give up most of the civilian horses for the use of the Army.)

Therefore the defense of the border-zone northwards from the shores of Lake Laatokka (Ladoga) became the task of 25 lightly armed and equipped Independent Battalions (Erillinen Pataljoona). Before the war these units were planned to be used by sending them to Soviet territory to conduct guerrilla (Sissi) warfare in Eastern Karelia, thus forcing the Red Army to divert men and material away from the Karelian Isthmus in order to defend the Murmansk Railway.

It was generally agreed that WWI-styled attritional trench warfare was a situation that should be avoided at all costs, since it was precisely the type of combat where the potential opponent excelled and would be able to use its material superiority to the fullest extent. Instead, the planners believed that bold attacks at the right time and place could lead to success. Delaying actions were planned to be executed in an active manner, and any passive defense was to be only temporary and something that had to be resorted to while preparing for an offensive action elsewhere. All these tactical schemes were devised in the firm knowledge that the potential foe would certainly have massive artillery and air superiority, and therefore operations in open terrain were consider impossible. Forests were considered to be the best terrain to conduct attacks, as even a large numerical and technical superiority was considered to be indecisive due to the possibilities open for small-unit maneuvers and the fact that a large force would be unable to bring its total firepower to bear.

The offensive mentality was further supported by peacetime military exercises, which were usually focused only on attack or delay-attack scenarios. While taking the offense tactically, the Finnish strategic thinking was firmly based on a defensive mindset. One of the key reasons for this was the influence of French military schools and military theories. Being widely seen as the strongest land army in Western Europe during the 1920’s, France was a natural place to send talented young officers for training. A large number of the officers who had received their military education in France were in key leading positions in later phases of Finnish history. At this time, Army planners became increasingly interested in fixed fortification zones and the possibilities they offered. The first fortification efforts in the Karelian Isthmus were, however, a short-lived project in the mid-1920’s and after this time the idea of building prepared defense lines was not priorized – global economical crisis soon ensured that Army was operating with a budget that barely allowed it to maintain training and exercises, and thus nothing could be spared to grand construction efforts (the Mannerheim Line fortifications will be covered in detail in a later post as we cover developments in the 1930s).

The book Airo and many other prominent Finnish military theorists praised and kept reading over and over again

In addition to their ideas of strategic defense and fortifications, the French-trained officers also brough home military ideas that were far older than the experiences of the Great War. When a young Finnish Captain named Akseli Airo was studying in the École Supérioure de Guerre, he was fascinated by the thoughts and ideas of one of his course books. He bought a copy for himself, and kept reading it and rereading it, making markings, notes and sidenotes up to and including the much later period when Airo led the operational planning of the Finnish Army.

The book Airo and many other prominent Finnish military theorists praised and kept reading over and over again was nothing less than L’art Militaire – Dans L’antiquité Chinoise, an old French translation and commentary on the Chinese classic “Art of War.” Later in his life Airo commented in an interview: “The art of war itself has remained unchanged. I have a French book that contains a compilation of the Chinese wisdom of military leadership and warfare, and the theses presented there are still valid today…it contains the whole art of war, and it was written two millennium ago. Naturally equipment and weapons change and will change in the future as well, but the principles are still the same and they will remain the same.”

Aside from the development of strategy and tactics suited to Finnish terrain and the strengths and weaknesses of the Finnish Army, there were two areas in which the Finnish Army were “early adopters.” The first was in the formation of experimental “elite” units and the second was in the adoption of Tanks and experiments with Combined Arms forces.

The Elite of the Finnish Army in the 1920’s

Bicycle Battalions (Polkupyöräpataljoona) were the first experimental light infantry units. Two were formed in the early 1920s and later on renamed the 1st and 2nd Jaeger Battalions (Jääkäripataljoona.) These units consisted of selected, physically fit conscripts and they were led by the “rising stars” of the Finnish Officer Corps. The Jaeger units were designed to be the spearhead of counterattacks, act as a delaying unit in the border zones in a surprise attack situation and generally to provide the HQ with light, mobile and well-trained fighting units. Later on the men trained in these units would form the future core group of the best divisions in the Finnish Army and would also lead the development of other “elite” combat units in the 1930s. These elite units would go on to play a decisive part in many of the strategic and tactical decision points of the Winter War – but all had their roots in the early Polkupyöräpataljoona.

In 1919 the newly created Finnish Armed Forces were shopping for new weaponry in France and, as a part of the initial spirit of experimentation within the Army, bought 32 modern Automitrailleuse à Chenilles Renault FT Modèle 1917 Tanks from the French in 1919 (with a further 2 in 1920), ensuring that the Finnish Armored Forces got off to a roaring start. The FT 17 tanks were shipped from Le Havre to Helsinki on the S/S Joazeiro and issued to the Finnish Army on the 26th of August 1919. The price of these tanks was 67 million Finnish Marks. All 32 tanks were factory-new, manufactured in 1918 – 1919 and had French register numbers in between 66151 – 73400. 14 of them were equipped with 37-mm tank guns and 18 had been equipped with 8-mm Hotchkiss M/1914 machineguns. The Finnish Army decided to call the version with the tank gun koiras (male) and the version with machinegun as naaras (female). For transporting the tanks on roads the Finnish Army also bought six Latil tractors with their trailers, these arrived on the same ship as the tanks.

Tanks, tractors and trailers were all issued to the newly formed (15th of July 1919) Hyökkäysvaunurykmentti (Tank Regiment), which had its garrison in the Santahamina military base at Helsinki. Following the French model, theTank Regiment was early on considered part of the field artillery and organised accordingly as artillery battalions and artillery batteries, which size-wise were the equivalent of companies and platoons. Since this was the first Finnish military unit of its type, in the beginning there were no Officers with the appropriate training. Early on, the most likely tactics for tanks were considered to be modernised cavalry tactics of sorts, so seven out of the first dozen officers of the Tank Regiment were transferred from the Cavalry. Recruits for this new military unit were selected with a preference for those with technical training and/or technical experience of any kind. To get the training going a French team of nine men lead by Captain Pivetau arrived to Finland in 1919 and trained the Finnish personnel in the basics of tank maintenance and warfare. In light of the political situation in 1919 and the geographic location of Finland, the FT 17 tank deal wasn’t exactly lacking in ulterior motives.

France apparently had political plans of its own in relationship to selling the Renault FT 17 tanks to Finland in 1919. The main intent of these plans was encouraging Finland to actively join the battle against the Russian Bolshevik government. The Finnish Government had no real interest in supporting the White Russians, since their leadership refused to accept Finland’s independence, so Finland refused to join the war, but this didn’t stop the French. Soon after delivery of the FT 17s, the French government exerted diplomatic pressure and demanded that Finland loan two of these tanks (one male and one female) to General Nikolai Yudenich’s North-Western Russian White Army, which in 1919 was operating from Estonia and advancing towards Petrograd (St. Peterburg). Ultimately the Finnish government gave in to political pressure on this matter.

On the 17th – 18th of October 1919 the two tanks were shipped to Tallinn, from where they moved to Narva two days later. They served with French-Russian crews and took part in the attack towards Kipi on the 27th – 31st of October 1919. Yudenich’s North-Western Army failed in its attack towards Petrograd in October 1919, retreated to Estonia and was disarmed there before being evacuated. Estonia used the two tanks for training its tank crews before returning them to Finland on the 9th of April 1920. Both of them proved to be in poor condition on return. Because of this the French government as compensation sent Finland two new additional Renault FT 17 tanks, which arrived n the S/S Ceres on the 21st of April 1920. (The French registration numbers for these additional tanks were 66614 and 67220). Arrival of these two new additional tanks increased the total number of Renault FT 17 tanks with the Finnish Army to 34 tanks.

Two Renault FT 17 tanks of the Finnish Army taking part in war games in the 1920’s. Koiras (gun-tank) with octagonal riveted turret is passing a partially smoke-covered naaras (machinegun-tank) version (photo reused from Jaeger Platoon with permission)

While budgetary constraints through the 1920s kept the force small, it was kept up to strength (some additional used units were purchased from France in 1926) and used largely as an experimental unit. While the British were the first to introduce a tank into combat use, for many the Renault FT 17 is the first modern tank. It was certainly the first to have the basic layout still found in most tanks today – the driver in the front part of the hull, the engine in the rear and weaponry in a rotating turret located on top of the hull. While obviously smaller than other tanks introduced during World War 1 it proved a surprisingly good design. By the end of WW1, French manufacturers had delivered 3,700 of the FT17s, many of which would remain in service with the French Army through to WW2.

While the French Army was the main customer for these tanks, they were also widely exported after World War 1. Export customers included Belgium, Brazil, China, Czechoslovakia, Great Britain, Finland, Greece, Italy, Japan, Manchuria, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain, USA and Yugoslavia. They were also provided as a military assistance to White Russians during Russian Civil War (1917 – 1923) and saw use in variety of other wars like Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939), Franco – Thai War (1940 – 1941), Chinese Civil War (1927 – 1937 and 1946 – 1950) and Chinese – Japanese War (1937 – 1945). Many of the Renault FT 17 tanks delivered to Russia ended up being captured by the Soviet Red Army, while some were taken over and used by Estonia until 1940. That same year the USA delivered some of them to Canada. In addition Italy (FIAT 3000), the Soviet Union (KS, MS-1 and MS-2) and the USA (6 Ton Tank M1917) started manufacturing either copies or their own tanks based on the FT 17 design.

The FT17 did have its limitations – the modest 35-horsepower tank engine was too weak for armoured vehicle of this size, giving it a very slow top speed (about equal to walking infantry). While it had a rather large (95-litre) gasoline tank, the maximum range was limited to a mere 35 kilometres. The two-man crew consisted of a driver and a very much over-burdened gunner/tank commander while the only signal equipment used in typical FT 17 tanks were signal flags, which the tank commander would wave when necessary. For Finland, like for many of the export customers for the FT 17 tanks, this was the first tank in use and the starting point for an Armored Corps in their Armed Forces.

Over the 1920’s, the Finnish military had plenty of opportunities for gathering experience with the tanks, which they did so to good effect. The French had originally suggested 20 kilometers as their maximum daily road march distance, but in 1925 this assumption was overturned by the successful performance of a 150 kilometre road mach. However this kind of test also revealed weaknesses in the design – the most problematic of which proved to be radiator fan belts, which for example needed to be replaced 21 times during the above mentioned 150 km road march. A Finnish-designed improved radiator fan belt introduced in 1926 had twice the working life of the original, but even its increased lifespan was too short to provide an answer to this problem. While replacing a broken radiator fan belt was easy and fast (for an experienced crew it took two minutes), the frequent breakages reduced the already limited march speed of the entire tank column. The engine also demanded constant maintenance – for example its oil had to changed after every 20 hours of use.

The Finnish Army was an early adopter of Armored Units and would later link these with the light Jaeger brigades, Mobile Artillery and Air Support in a combined arms unit which would, in the 1930’s, become the 21st Armored Division, but few people were aware of this before the Winter War.

In 1926, Major Olavi Sahlgren reported that in addition to the already limited maximum road speed (7.5 km/h) of Renault FT 17: “On a road march, after only 50 – 60 kilometres the technical losses are around 25 % and frequent technical problems demanding repairs reduce the actual march speed of the Renault tanks on the road to only about 4 kilometres per hour.”Because of this he noted that Renault tanks simply were not suitable for mobile warfare. Around 1927-28 the Finnish Army tested the old Renault FT 17 tanks in deep snow and against various kinds of antitank obstacles. In these tests the FT 17 performed surprisingly well in deep snow, but when it came to tightly packed snow-drifts or antitank-obstacles its capabilities proved much less spectacular. The design of the FT 17 had some obvious inbuilt limitations to begin with. These included the very slow maximum speed (making the tank an easy target for any antitank weapon), thin armour designed to provide protection only against small arms fire and shrapnel and a low-velocity 37-mm Hotchkiss SA-18) L/21 tank gun, which was a poor weapon against other tanks. When testing the armour-penetrating capability of this tank gun, its ammunition was noted as so poor that it was considered unable to reliably penetrate even 10-mm of armour plate from any useful distance.

The vehicle also lacked a radio (and had very limited room even for adding one) and the tank commander/gunner/loader was over burdened with his many tasks. Signalling between tanks took place using small flags, which the tank commander waved when necessary and internally through yelling, hand signals and physical contact. With signalling equipment as rudimentary as this, it is hardly surprising that the most commonly used message was “Do as I Do”. In 1922 the Hyökkäysvaunurykmentti (Tank Regiment) shad uggested acquiring radio-equipment for eight tanks, which would have been reserved for company commanders and platoon leaders, but the suggestion was not approved due to cost.

The Finnish Army also experimented on a small scale with combined arms forces, tanks operating in conjunction with infantry, artillery and air support. The stated intent was to develop an effective method for counter-attacking any major attack on the Karelian Isthmus, the obvious direction for any major offensive from the Soviet Union. Finnish Officers of the Hyökkäysvaunurykmentti and of other units assigned to Combined Arms tactical experimentation were avid (and apt) students of foreign writings on this subject, as we will cover in more detail when we discuss the development of Finnish Armored doctrine through the 1930s and the highly effective use of Finnish Armor in the Winter War, both in the defensive phase over the Winter and in the Spring Offensive of 1940 that took the Kannaksen Armeija (Army of the Isthmus, under the command of Lt.Gen Hugo Viktor Österman) to the outskirts of Leningrad whilst virtually annihilating or capturing all the Red Army units they fought against.

When acquired by Finland in 1919, the Renault FT 17 was likely the most advanced tank in the world and remained an effective fighting vehicle through the 1920s, but as tank development in the 1930’s moved ahead at a rapid rate, it became seriously outdated. In 1932, the commander of the Hyökkäysvaunurykmentti reported to the Finnish Armed Forces General Headquarters that tank units equipped with Renault FT 17 tanks were unfit for modern mobile warfare.

In 1933 the Finnish Army acquired several new tanks for testing, with results that we will see as we cover the Finnish military of the 1930s. Suffice it at this stage to say that as a result of ongoing experimentation with tanks and armored tactics through the 1920’s, the 1933 Tank Evaluation Program, the Armaments Program of the latter part of the 1930’s, the Combined Arms Experimental Combat Program and the experiences of the Finnish Volunteer Unit (Pohjan Pohjat) in combat in the Spanish Civil War, the Finnish Army had a well-trained and highly effective Armored Force in being on the start of the Winter War.

As we can see, the Finnish Army of the 1920’s developed into a national army with a doctrine that was based on a combination of experience fighting on the eastern front on World War One, the guerrilla and small-unit fighting of the Heimosodat and the more classical traditions of the French and of Sun Tzu. In the Jaeger Units, the Finnish Army had light, mobile and well-trained infantry, and in the acquisition of the Renault FT17 tanks lay the foundation of the elite Panzer Divisions that the Finnish Army would field in the Winter War. And while the Artillery Guns were antiquated, in General Nenonen, the Finnish Army had an Artillery Commander whose genius would shine in the war years to come. These would all be major factors in the restructuring and reequipping of the Finnish Army in the 1930’s.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

One Response to The Finnish Army of the 1920’s – Part I