There were three further purchases that would be made before the Munich Crisis of late 1938 – these were for a Torpedo Bomber for the Merivoimat Air Arm, and an Observation, Artillery Control and general purpose Light Aircraft for the Ilmavoimat, and additional fighters for the Merivoimat Air Arm.

Background to the Torpedo Bomber Purchase of 1938

The Soviet Baltic Fleet was a threat that was always in the minds of the Finnish General Staff – the existence of a strong Soviet Baltic Fleet opened up the possibility of an amphibious movement to outflank the defences of the Karelian Isthmus and hence the ever-present emphasis the Finns put on the Coastal Defence Batteries and the Coastal Defence Divisions as well as on the Marine Division and the Torpedo Boat and Fast Minelayer flotillas. Bottling up the Soviet Navy in Krondstadt was one of the primary missions of the Merivoimat and also for the nacent Merivoimat Air Arm.

At the end of 1937, the Merivoimat Air Arm’s torpedo bomber forces consisted of a small number of now-obsolete Blackburn Ripons. The existing Blackburn Ripon’s were considered to be getting long in the tooth and short of performance and a more modern aircraft was planned to be acquired – not to replace the Ripons as these could still be used for patrolling areas such as the Gulf of Bothnia – but to augment them. In 1938, the Merivoimat Budget made provision for the purchase of a Squadron of new Torpedo Bombers as well as an additional squadron of Dive Bombers. Accordingly, the Ilmavoimat Procurement Team searched for such an aircraft and, as with all their purchases, evaluated a number of types before maing a decision.

In early to mid-1938, there were a number of Torpedo Bombers already in service, but some of them were either obsolete, or nearly so. However, the procurement team went ahead and evaluated many of these on the off-chance that a good aircraft might be missed. And, as always, there was the dual question of both cost and availability to be assessed – and aircraft manufacturers, particularly those in Britain, France and Germany, were often overruled by their respective Governments when it came down to actual delivery. The following aircraft were evaluated over the first six months of 1938.

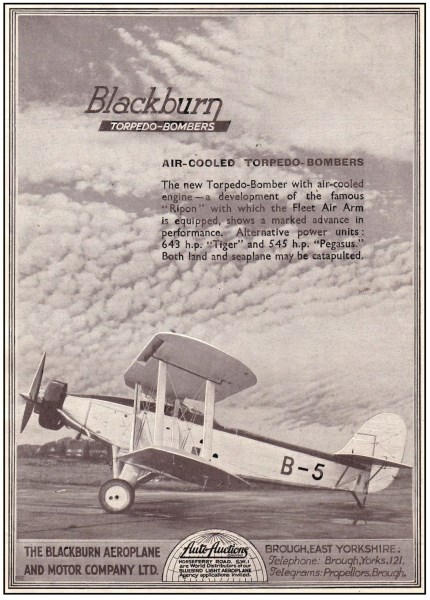

Blackburn Baffin (UK)

With a crew of 2, the Baffin was powered by a single Bristol Pegasus I.M3 9-cylinder radial engine 565 hp (421 kW) giving the aircraft a maximum speed of 136 mph. Range was 490 miles, service ceiling was 15,000 feet and armament consisted of 1 × forward firing fixed 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers gun and × 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis gun in the rear cockpit. Bombload consisted of 1 × 1,800 lb (816 kg) 18 in (457 mm) torpedo or 1,600 lb (726 kg) of bombs.

In the early 1930’s the torpedo bomber squadrons of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm were equipped with the Blackburn Ripon. While the Ripon had only entered service in 1930, it was powered by the elderly water-cooled Napier Lion engine, and it was realised that replacing the Lion by a modern air-cooled radial engine would increase payload and simplify maintenance.

In 1932 Blackburn decided to build two prototypes of radial-engined Ripons, one powered by an Armstrong Siddeley Tiger and the second by a Bristol Pegasus, as a private venture (i.e. without an order from the Air Ministry). The Pegasus-engined prototype first flew on 30 September 1932, and after testing was chosen ahead of the Tiger-powered aircraft as a short-term replacement for the Ripon. Initial orders were placed for 26 new-build aircraft and 38 conversions of Ripon airframes, production beginning in 1933. A further 26 conversions of Ripons into Baffins were ordered in 1935 because of reliability problems associated with the Armstrong Siddeley Tiger engines powering Blackburn Sharks, and the desire to expand the strength of the Fleet Air Arm.

In the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm, the Baffins were seen as a short-term replacement for the Ripons and by late 1937 were being replaced by the Blackburn Shark and the Fairey Swordfish. The Merivoimat Air Arm had no intention of replacing one obsolete Torpedo Bomber with another, especially in light of otherand rather more modern potential torpedo bombers available. After an initial evaluation, the Baffin was immediately removed from further consideration.

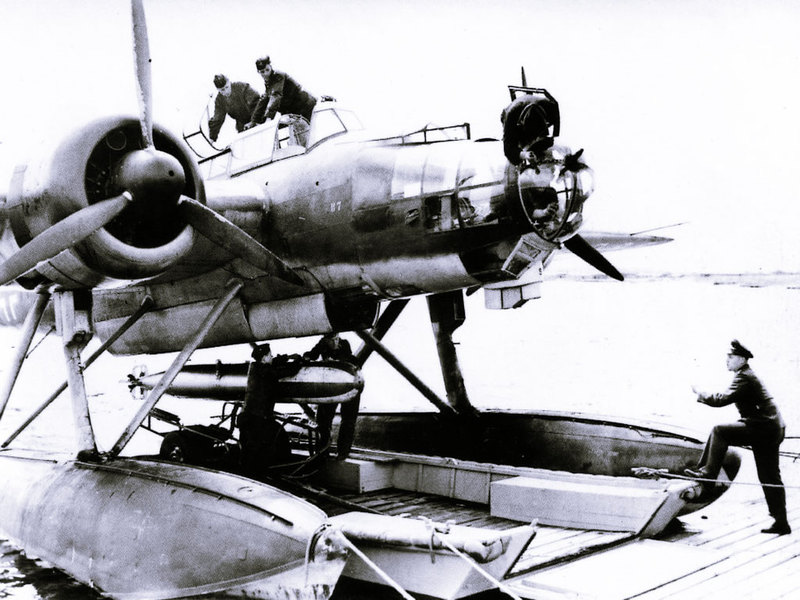

Blohm and Voss Ha140 (Germany)

With a crew of 3, the Ha140 V2 was powered by 2 BMW 132K 9 cynclinder single row supercharged air coold radial engines (970hp each), had a maximum speed of 207mph, a range of 715 miles and a service ceiling of 16,400 feet. Defensive armament consisted of 1× 7.9 mm MG15 machine gun in the nose and 1× MG 15 machine gun at the dorsal hatch. Bombload consisted of 1× 952 kg (2,095 lb) torpedo or 4× 250 kg (550 lb) bombs.

The Blohm and Voss Ha 140 was a German multi-purpose seaplane which firest flew in 1937 and which was designed for use as a torpedo bomber or long-range reconnaissance aircraft. The Ha 140 was a developed as a twin-engine floatplane, with an all-metal structure and an inverted gull wing, similar to the larger Ha 139. The crew consisted of a pilot and radio operator, with a gunner in a revolving turret in the nose or in a second gun position to the rear. The torpedo or bomb load was accommodated in an internal bomb bay. Three prototypes were built and flew test flights in 1937.

In Germany the design was not carried any further, as the similar Heinkel He 115 was selected for service. The Merivoimat evaluated the aircraft but the test team reported back that the handling was unacceptable. It was also indicated to the Maavoimat that Blohm & Voss did not have the production capacity to meet any orders for the aircraft. A further factor was that the Luftwaffe had selected the Heinkel He115 in preference to the Ha140 and this was the final nail in the coffin as far as the evaluation was concerned. The Ha140 was removed from further consideration.

The Douglas TBD Devastator (USA)

The Douglas TBD Devastator was a United States Navy torpedo bomber, ordered in 1934, first flying in 1935 and entering service in 1937. At that point, it was the most advanced aircraft flying for the USN and possibly for any navy in the world. Ordered on 30 June 1934, flying for the first time on 15 April 1935 and entered into a U.S. Navy competition for new bomber aircraft to operate from its aircraft carriers, the Douglas entry was one of the winners of the competition. Other than requests by test pilots to improve pilot visibility, the prototype easily passed its acceptance trials that took place from 24 April-24 November 1935 at NAS Anacostia and Norfolk bases. After successfully completing torpedo drop tests, the prototype was transferred to the Lexington for carrier certification. The extended service trials continued until 1937 with the first two production aircraft retained by the company exclusively for testing. A total of 129 of the type were purchased by the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), and starting from 1937, began to equip the carriers Saratoga, Enterprise, Lexington, Wasp, Hornet, Yorktown and Ranger.

A U.S. Navy Douglas TBD-1 Devastator of Torpedo Bomber Squadron VT-6 being used by the Merivoimat Test Team to make a practice torpedo drop in February 1938. The Devastator tested by the Merivoimat required a crew of 3 (Pilot, Torpedo Officer/Navigator, Radioman/Gunner) and was powered by a single Pratt & Whitney R-1830-64 Twin Wasp radial engine of 900 hp (672 kW) giving a maximum speed of 206mph, a range of 535 miles with a Torpedo and 716 miles with a 1,000lb bombload. Service ceiling was 19,500 feet and defensive armament consisted of 1 × forward-firing 0.30 in (7.62 mm) or 0.50 (12.7 mm) or machine gun and 1 × 0.30 in (7.62 mm) machine gun in rear cockpit (later increased to two). Bombload consisted of 1 x Torpedo or 1 x 1,000lb bomb (or 2 x 500lb bombs or 12 x 100lb bombs).

The Devastator marked a large number of “firsts” for the U.S. Navy. It was the first widely-used carrier-based monoplane as well as the first all-metal naval aircraft, the first with a totally-enclosed cockpit, the first with power-actuated (hydraulically) folding wings; it is fair to say that the TBD was revolutionary. A semi-retractable undercarriage was fitted, with the wheels designed to protrude 10 in (250 mm) below the wings to permit a “wheels-up” landing with only minimal damage. A crew of three was normally carried beneath a large “greenhouse” canopy almost half the length of the aircraft. The pilot sat up front; a rear gunner/radio operator took the rearmost seat, while the bombardier occupied the middle seat. During a bombing run, the bombardier lay prone, sliding into position under the pilot to sight through a window in the bottom of the fuselage, using the Norden Bombsight.

The normal TBD offensive armament consisted of either a 1,200 lb (540 kg) Bliss-Leavitt Mark 13 aerial torpedo or a 1,000 lb (450 kg) bomb. Alternatively, three 500 lb (230 kg) general-purpose bombs: one under each wing and one under the fuselage, or 12 x 100 lb (45 kg) fragmentation bombs: six under each wing, could be carried. This weapons load was often used when attacking Japanese targets on the Gilbert and Marshall Islands in 1942. Defensive armament consisted of a .30 in (7.62 mm) machine gun for the rear gunner. Fitted in the starboard side of the cowling was either a .30 in (7.6 mm) or .50 in (12.7 mm) machine gun. The powerplant was a Pratt & Whitney R-1830-64 Twin Wasp radial engine of 850 hp (630 kW), an outgrowth of the prototype’s Pratt & Whitney XR-1830-60/R-1830-1 of 800 hp (600 kW). Other changes from the 1935 prototype included a revised engine cowling and raising the cockpit canopy to improve visibility.

Dornier D022 (Germany)

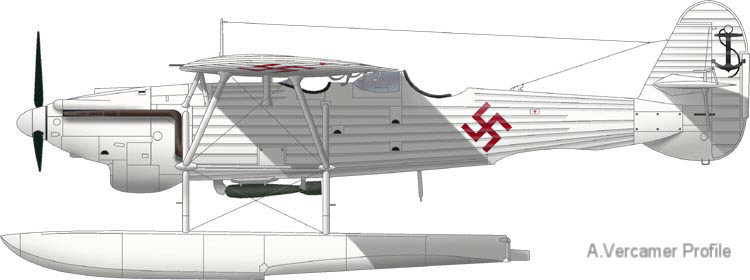

The Do22 had a crew of 3 (Pilot, Gunner and Radio Operator) amd was powered by a single Hispano-Suiza 12Ybrs V-12 liquid cooled inline piston engine producing 641 kW (860 hp) and giving a maximum speed of 217mph. Range was 1,428 miles and service ceiling was 29,500 feet. Armament consisted of 4 × 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 15 machine guns in nose, ventral and rear cockpit positions. Bombload consisted of 1 × 800 kg (1,764 lb) torpedo or 4 × 50 kg (110 lb) bombs. The example shown in the photo above is a Yugoslav Do22.

The Do 22 was an improved version of the Do C 2 floatplane, which was manufactured in 1930 and in one sample sent to Colombia. When after WWI manufacturing of aicraft in Germany was halted by the Treaty of Versailles, Dornier simply moved to the other side of Lake Constance by setting up a factory at Altenrheim in Switzerland. In 1934 the Dornier Company began work on a three-seat multi-purpose military monoplane suitable for operation with float, wheel or ski undercarriages, and intended solely for export. This was the Do C3, with two prototypes being built, with the first being flown in 1935. It was a parasol wing monoplane of fabric covered all-metal construction. Its slightly swept-back wing was attached to the fuselage by bracing struts, while its two floats were braced to both the wing and fuselage. It was powered by a Hispano-Suiza 12Ybrs engine driving a three-bladed propeller, and could carry a single torpedo or bombs under the fuselage, while defensive armament was one fixed forward firing machine gun, two in the rear cockpit and one in a ventral tunnel. The first production model, known as Do 22/See when fitted with floats, first flew on 15 July 1938 from Dornier’s factory at Friedrichshafen, Germany, although it did incorporate parts made in Switzerland.

While the Luftwaffe was not interested in the aircraft, some 30 Do22’s were sold to Yugoslavia, Greece and Latvia. In March 1939, a prototype with conventional landing gear (Do 22L) was completed and test flown, but did not enter production. However, four Do22’s did end up serving with the Merivoimat Air Arm over the last two months of the Winter War, seeing action once when they sank a Russian submarine attempting to enter the waters of the Gulf of Finland from Leningrad.

The Latvian Air Force had ordered four Do22’s – these had not been delivered when the Soviet Union occupied Latvia in June 1940 (which occurred despite the war with Finland not going well) and the aircraft were as a result retained by Germany. These four aircraft were subsequently sold by a German arms dealer, Josef Veltjens (of whom we will hear more now and then), to a “Swedish” company which after taking delivery, promptly “sold” the aircraft to Finland, where they were taken into service with the Maavoimat in August 1940. These aircraft were almost brand new, even though they were bought as “second hand”. The aircraft were flown by Swedes from Friedrichshafen (Germany) on 25 July to Sweden and then on to Helsinki Malmi airfield, where they landed on 1 Aug. Used for maritime patrolling, the Do 22s saw action once when they torpdeoed two Soviet submarines on the surface in late August 1940 as they were trying to breach the Finnish mine fields in front of Leningrad, sinking one. They remained in service until 18th October 1944 and were scrapped in 1952.

The four aircraft destined for Latvia (designated Do-22K1) were built in Friedrichshafen but were not delivered before the Soviet occupation. These aircraft eventually made their way to Finland instead. The above illustration is how they might have appeared if delivered to Latvia as had originally been intended.

The Fairey Swordfish (UK)

The Swordfish was based on a Fairey Private Venture (PV) design; a proposed solution to the Air Ministry requirements for a spotter-reconnaissance plane, spotter referring to observing the fall of a warship’s gunfire. A subsequent Air Ministry Specification S.15/33, added the torpedo bomber role. The “Torpedo-Spotter-Reconnaissance” prototype TSR II (the PV was the TSR I) first flew on 17 April 1934. It was a large biplane with a metal frame covered in fabric, and utilized folding wings as a space-saving feature for aircraft carrier use. An order was placed in 1935 and the aircraft entered service in 1936 with the Fleet Air Arm (then part of the RAF), replacing the Seal in the torpedo bomber role. By 1938 the Fleet Air Arm (now under Royal Navy control) had 13 squadrons equipped with the Swordfish Mark I.

The Fairey Swordfish had a Crew of 3 (pilot, observer, and radio operator/rear gunner) and was powered by a single Bristol Pegasus IIIM.3 radial engine of 690 hp (510 kW) giving a maximum speed of 139mph, a ramge of 546 miles and a service ceiling of 19,250 feet. Defensive Armament consisted of 1 × fixed, forward-firing .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers machine gun in the engine cowling and 1 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis or Vickers K machine gun in the rear cockpit. Bombload consisted of 1 × 1,670 lb (760 kg) torpedo or 1,500 lb (700 kg) mine under the fuselage or 1,500 lb of bombs under the fuselage and wings.

The Merivoimat eliminated the Swordfish from consideration immediately, considering it outdated and failing minimum performance requirements.

OTL Note: The primary weapon was the aerial torpedo, but the low speed of the biplane and the need for a long straight approach made it difficult to deliver against well-defended targets. Swordfish torpedo doctrine called for an approach at 5,000 ft (1,500 m) followed by a dive to torpedo release altitude of 18 ft (5.5 m). Maximum range of the early Mark XII torpedo was 1,500 yd (1400 m). The torpedo traveled 200 yd (180 m) forward from release to water impact, and required another 300 yd (270 m) to stabilise at preset depth and arm itself. Ideal release distance was 1,000 yd (900 m) from target if the Swordfish survived to that distance. Swordfish flying from the British aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious made a very significant strike on 11 November 1940 against the Italian navy during the Battle of Taranto, Italy, sinking or disabling three Italian battleships and a cruiser lying at anchor. The planning for this strike had its origins in the audacious attack by Finnish torpedo bombers and dive bombers on the Soviet Baltic Fleet in Krondstadt in which many Soviet ships were sunk. In the aftermath, Taranto was visited by the Japanese naval attache from Berlin, who later briefed the staff who planned the attack on Pearl Harbor. Swordfish also flew anti-shipping sorties from Malta.

In May 1941, a Swordfish strike from HMS Ark Royal was vital in damaging the German battleship Bismarck, preventing it from escaping back to France. The low speed of the attacking aircraft may have acted in their favour, as the planes were too slow for the fire-control predictors of the German gunners, whose shells exploded so far in front of the aircraft that the threat of shrapnel damage was greatly diminished. The Swordfish also flew so low that most of the Bismarck’s flak weapons were unable to depress enough to hit them. The Swordfish aircraft scored two hits, one which did little damage but another that disabled Bismarck’s rudder, making the warship unmanueverable and sealing its fate. The Bismarck was destroyed less than 13 hours later.

The problems with the aircraft were starkly demonstrated in February 1942 when a strike on German battleships during the Channel Dash resulted in the loss of all attacking aircraft. With the development of new torpedo attack aircraft, the Swordfish was soon redeployed successfully in an anti-submarine role, armed with depth-charges or eight “60 lb” (27 kg) RP-3 rockets and flying from the smaller escort carriers or even Merchant Aircraft Carriers (MAC) when equipped for rocket-assisted takeoff (RATO). Its low stall speed and inherently tough design made it ideal for operation from the MAC carriers in the often severe mid Atlantic weather. Indeed, its takeoff and landing speeds were so low that it did not require the carrier to be steaming into the wind, unlike most carrier-based aircraft. On occasion, when the wind was right, Swordfish were flown from a carrier at anchor.

Swordfish-equipped units accounted for 14 U-boats destroyed. The Swordfish was meant to be replaced by the Albacore, also a biplane, but actually outlived its intended successor. It was, finally, however, succeeded by the Fairey Barracuda monoplane torpedo bomber. The last of 2,392 Swordfish aircraft was delivered in August 1944 and operational sorties continued in to January 1945 with anti-shipping operations off Norway (FAA Squadrons 835 and 813), where the Swordfish’s manouvreability was essential. The last operational squadron was disbanded on 21 May 1945, after the fall of Germany; and the last training squadron was disbanded in the summer of 1946.

The Fairey Albacore (UK)

The Fairey Albacore had a crew of 3 and was powered by a single Bristol Taurus II (Taurus XII) 14-cylinder radial engine of 1,065 hp (1,130 hp) / 794 kW (840 kw) giving a maximum speed of 161 mph with a range of 930 miles (with torepedo) and a service ceiling of 20,700 feet. Defensive armament consisted of 1 × fixed, forward-firing .303 in (7.7 mm) machine gun in the starboard wing and 1 or 2 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K machine guns in the rear cockpit. Bombload consisted of 1 × 1,670 lb (760 kg) torpedo or 2,000 lb (907 kg) bombs.

The Fairey Albacore, was conceived as a replacement for the aging Fairey Swordfish, which had entered service in 1936 and the prototypes were built to meet Specification S.41/36 for a three-seat TSR (torpedo /spotter /reconnaissance) for the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm to replace the Fairey Swordfish. Like the Swordfish, the Albacore was fully capable of dive bombing: “The Albacore was designed for diving at speeds up to 215 knots(400 km/h) lAS with flaps either up or down, and it was certainly steady in a dive, recovery being easy and smooth…” and the maximum under wing bomb load was 4 x 500 lb bombs or s single torpedo. The Albacore had a more powerful engine than the Swordfish and was more aerodynamically refined. It offered the crew an enclosed and heated cockpit. The Albacore also had features such as an automatic liferaft ejection system which triggered in the event of the aircraft ditching.

At the time of the Merivoimat evaluation in early 1938, the Fairey Albacore was “design only.” The evaluation team did however review the specifications and Fairey design drawings and considered the aircraft both outdated in design and lacking in speed and defensive armament. This was expressed somewhat diplomatically to the Fairey team, who in typical British fashion shrugged of what they perceived as criticism from mere foreigners.

OTL Note: The first of two prototypes flew on 12 December 1938 and production of the first batch of 98 aircraft began in 1939 – these began entering service in March 1940. Early Albacores were fitted with the Bristol Taurus II engine and those built later received the more powerful Taurus XII. Boscombe Down testing of the Albacore and Taurus II engine, in February 1940, showed a maximum speed of 160 mph (258 km/h), at an altitude of 4,800 ft (1,463 m), at 11,570 lb (5,259 kg), which was achieved with four under-wing depth charges, while maximum speed without the depth charges was 172 mph (277 km/h). Some 800 in total were built. Initially, the Albacore suffered from reliability problems with the Taurus engine, although these were later solved, so that the failure rate was no worse than the Pegasus that equipped the Swordfish. It remained less popular than the Swordfish, however, as it was less agile, with the controls being too heavy for a pilot to take effective evasive action after dropping a torpedo.

Fieseler Fi 167 (Germany)

The Fieseler Fi 167 was a 1930s German biplane torpedo and reconnaissance bomber designed for the new aircraft carriers then being planned. In early 1937, the Riechsluftfahrtministerium or German Ministry of Aviation issued a specification for a carrier-based torpedo bomber to operate from Germany’s first aircraft carrier, the Graf Zeppelin construction of which had started at the end of 1936. The specification was issued to two aircraft producers, Fieseler and Arado, and demanded an all-metal biplane with a maximum speed of at least 300 km/h (186 mph)a range of at least 1,000 km and capable both of torpedo and dive-bombing. By the summer of 1938 the Fiesler design proved to be superior to the Arado design, the Ar 195.

With a Crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner) and powered by a Daimler-Benz DB 601B liquid cooled inverted V12, of 1,100 hp, the Fi 167 had a maximum speed of 202mph, a range of 808 miles and a service ceiling of 26,900 feet. Defensive armament consisted of 1 fixed forward firing 7.92 mm MG 17 machine gun and 1 rear facing MG-15 machine gun on a flexible mount. Bombload consisted of 1 × 1000 kg (2,200 lb) bomb or 1 × 765 kg (1,685 lb) torpedo or 1 × 500 kg (1,100 lb) bomb plus 4 × 50 kg (110 lb) bombs.

After two prototypes (Fi 167 V1 & Fi 167 V2), twelve pre-production models (Fi 167 A-0) were built. These had only slight modifications from the prototypes. The aircraft exceeded by far all requirements, had excellent handling capabilities and could carry about twice the required weapons payload. Like the famous Fieseler Fi 156 Storch, the Fi 167 had surprising slow-speed capabilities; the plane would be able to land almost vertically on a moving aircraft carrier. One notable demonstration showed the types excellent low speed performance when Fiesler himself flew the Fi 167 from 9,800 ft. to 100 ft. while remaining stationary over one spot and all the time retaining full control. For emergency landings at sea the Fi 167 could jettison its landing gear, and airtight compartments in the lower wing would help the aircraft stay afloat at least long enough for the two-man crew to evacuate. The Merivoimat evaluation team considered that the Fi 167 handling was superb.

OTL Note: Since the Graf Zeppelin was not expected to be completed before the end of 1940, construction of the Fi 167 had a low priority. When construction of the Graf Zeppelin was stopped in 1940, the completion of further aircraft was stopped and the completed examples were taken into Luftwaffe service in the “Erprobungsgruppe 167”. When construction of the Graf Zeppelin was resumed in 1942 the Ju 87C took over the role as a reconnaissance bomber, and torpedo bombers were no longer seen to be needed. Nine of the existing Fi 167 were sent to a coastal naval squadron in the Netherlands and then returned to Germany in the summer of 1943. After that they were sold to Croatia, where their short-field and load-carrying abilities (under the right conditions, the aircraft could descend almost vertically) made it ideal for transporting ammunition and other supplies to besieged Croatian Army garrisons between their arrival in September 1944 and the end of the War. The remaining planes were used in the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt (“German Aircraft Experimental Institute”) in Budweis, Czechoslovakia, for testing different landing gear configurations. The large wing area and resulting low landing speeds made the Fi 167 ‘too good’ at this task, so in order to test landings with higher wing loads, the two test aircraft had their lower wings removed just outboard of the landing gear. No examples of this aircraft survive.

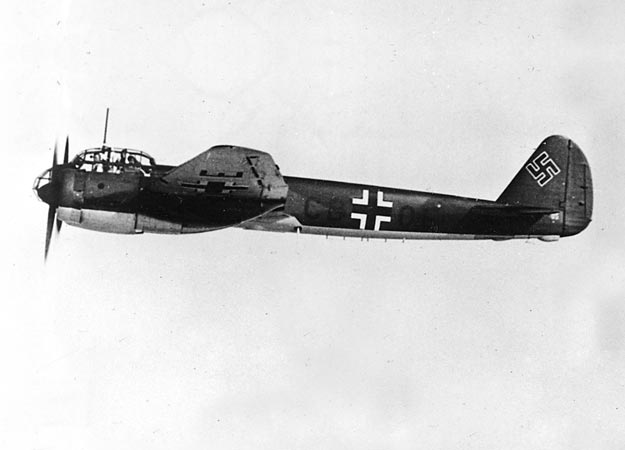

Heinkel He111 (Germany)

The Ilmavoimat had looked at a prototype Heinkel He111 as early as 1935 as a potential acquisition. However at that early stage in its development, the aircraft was still in development, delivery times could not be guaranteed and the cost as compared to the Italian SM.81 aircraft was on the high side. By early 1938, the situation was somewhat different. The He 111B had gone into limited production in late 1936, followed by the He 111E-1’s in 1937 – the first of which came of the production line in February 1938, in time for a number of these aircraft to serve in the Condor Legion during the Spanish Civil War in March 1938. The He 111F was next, being built and entering service in 1938 also and then came the He 111J – the version that the Merivoimat evaluated and tested.

The He 111 was in production in 1938. Heinkel constructed a factory at Oranienburg and on 4 May 1936, construction began. Exactly one year later the first He 111 rolled off the production line.

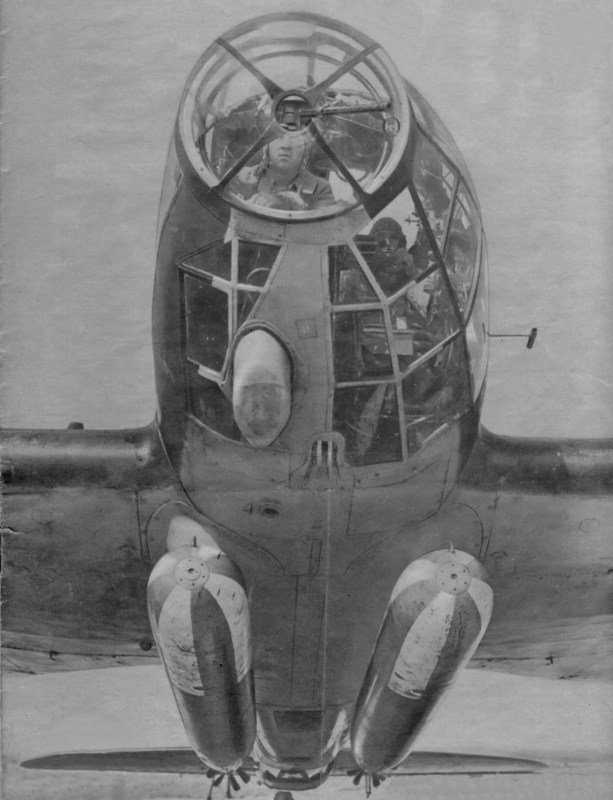

Heinkel He 111-J carrying two torpedoes: With a Crew of 4, the He111J had a maximum speed of 230mph, a range of 1030 miles and a service ceiling of 22,966 feet. Defensive armament consisted of 3 machine guns (Nose, Dorsal and Ventral) and the bombload consisted of two torpedoes.

The He 111J was powered by the DB600 engines and was intended from the start as a torpedo bomber. As a result, it lacked an internal bomb bay and carried two external torpedo racks. The RLM gave an order for the bomb bay to be retrofitted; this variant became known as the J-1. In all but the powerplant, it was identical to the F-4. The He 111’s low-level performance attracted the interest of the Kriegsmarine. The Kriegsmarine believed the He 111 would make an excellent torpedo bomber, and as a result, the He 111J was produced. The J was capable of carrying torpedoes and mines.

The Kriegsmarine eventually dropped the program as they deemed the four man crew too expensive in terms of manpower. The RLM however, had progressed too far with the development, and continued to build the He 111 J-0. Some 90 (other sources claim 60) were built in 1938 and were then sent to Küstenfliegergruppe 806. The He 111 J-0 was powered by the DB 600G without retractable radiators. It could carry a 2,000 kg (4,410 lb) payload. Few of the pre-production J-0s were ever fitted with the DB 600G. Instead, the DB 600 was used and the performance of the powerplant left much to be desired.

The Merivoimat evaluation team advised that the He 111 possessed excellent flight characteristics. It was steady to fly, unwavering in level flight and completely predictable as well as having very good low-level maneuverability and providing a very good bombing or torpedo attack platform.

Heinkel He115 (Germany)

In 1935, the German Reich Air Ministry (Reichsluftfahrtministerium or RLM) produced a requirement for a twin engined general purpose floatplane, suitable both for patrol and for anti-shipping strikes with bombs and torpedoes as well as for aerial mine-laying. Proposals were received from both Heinkel Flugzeugwerke and from Blohm & Voss’ aircraft subsidiary, Hamburger Flugzeugbau, and on 1 November 1935, orders were placed with both Heinkel and Hamburger Flugzeugbau for three prototypes each of their prospective designs, the He 115 and the Ha 140. The first Heinkel prototype flew in August 1937, with testing proving successful. The He 115 was selected over the Ha 140 early in 1938, resulting in an order for an additional prototype and 10 pre-production aircraft. Meanwhile, the first prototype was used to set a series of international records for floatplanes over 1,000 km (621 mi) and 2,000 km (1,243 mi) closed circuits at a speed of 328 km/h (204 mph). Four further protoypes were built between late 1937 and early 1939, introducing a glassed cockpit amd struts in place of wire. There were also variations on armament.

With a Crew of 3, the Heinkel He 115 was powered by 2 × BMW 132K 9-cylinder radial engines of 630 kW (970 hp) each giving a maximum speed of 203 mph with a combat radius of 1,305 miles and a service ceiling of 17,100 feet. Defensive armament consisted of 1 × fixed 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17 machine gun and 1 × flexible 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 15 machine gun in dorsal and nose positions. Bombload consisted of five 550 lb (250kg) bombs, or two such bombs and one torpedo of 1,760 lb (800kg), or one 2,030 lb (920 kg) sea mine.

OTL Note: Seven He 115A-2’s (Five of them He 115Ns) served in the Royal Norwegian Navy Air Service against the Germans during the Norwegian Campaign of April–June 1940. The Norwegians signed another order of six He 115Ns in December 1939, with delivery estimated to March/April 1940. The delivery of this second order was however pre-empted by the German invasion of Norway on 9 April 1940. Four of the Norwegian aircraft (F.52, F.56, F.58 and F.64) made the journey to the United Kingdom after the 10 June 1940 surrender, a fifth (F.50) escaping to Finland, landing on Lake Salmijärvi in Petsamo. A sixth He 115 (F.54) also tried to make the journey to Britain, but was lost over the North Sea. The last of the Norwegian He 115s, was unserviceable at the time of the evacuation and had to be abandoned at Skattøra, later being repaired and flown by the Germans.

One Norwegian aircraft (F.50) escaped to Finland, where it was interned, and later used by the Finnish Air Force’s LLv.44 to ferry sissi troops. In this role, it proved valuable as it did not require a vast open space to land on, but instead could touch down on lakes. It served in this role until it crashed on enemy fire behind Soviet lines in East Karelia on 4 July 1943. Two others were leased from Germany for similar purposes in 1943-44. The Swedish Air Force operated 12 He 115A-2s. Another six aircraft were ordered, but never delivered due to the outbreak of World War II. They were sturdy and well liked by their crews, and were not taken out of use until 1952. The Swedish He 115’s were kept on duty throughout World War II and made a valuable contribution to protecting and enforcing Swedish neutrality. They replaced the outdated Heinkel HD 16s in the torpedo bomber role and also served as a regular bomber, for smoke screening and for long-range reconnaissance missions. Five of the 12 He115’s were lost in accidents during their service with the Swedish Air Force.

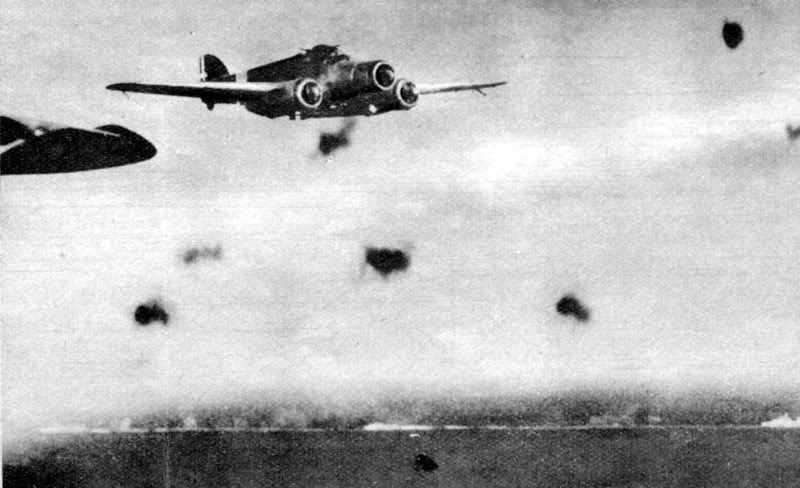

Junkers Ju88 (Germany)

As mentioned earlier, the Ilmavoimat had evaluated the Junkers Ju88 prototype in early 1937 and at that stage, liked the aircraft and could see its potential with its projected bombload of 6,600lb and a speed of 300mph+. However, with the problems still being worked on, a number of prototypes in development and production not yet in sight, the team had recommended a “wait and see” approach with a further evaluation to be carried out in 1938. In the event, it was the Merivoimat that again evaluated the Ju88 a year later, in early 1938, as they searched for an effective Torpedo Bomber.

In August 1935, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium submitted its requirements for an unarmed, three-seat, high-speed bomber, with a payload of 800-1,000 kg (1,760-2,200 lb). Junkers presented their initial design in June 1936, and were given clearance to build two prototypes. The aircraft’s first flight was made by the prototype Ju 88 V1, which bore the civil registration D-AQEN, on 21 December 1936. When it first flew, it managed about 580 km/h (360 mph) and Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe was ecstatic. It was an aircraft that could finally fulfill the promise of the Schnellbomber, a high-speed bomber. The streamlined fuselage was modeled after its contemporary, the Dornier Do 17, but with fewer defensive guns because the belief still held that a high speed bomber could outrun late 1930s-era fighters. However, production was delayed drastically with developmental problems.

In October 1937 Generalluftzeugmeister Ernst Udet had ordered the development of the Ju 88 as a heavy dive bomber. This decision was influenced by the success of the Ju 87 Stuka in this role. The Junkers development center at Dessau gave priority to the study of pull-out systems, and dive brakes. The first prototype to be tested as a dive bomber was the Ju 88 V4 followed by the V5 and V6. These models became the planned prototype for the A-1 series. The V5 made its maiden flight on 13 April 1938, and the V6 on 28 June 1938 and it was these versions that the Maavoimat team evaluated and tested. Both the V5 and V6 were fitted with four-blade propellers, an extra bomb bay and a central “control system”, the wings were strengthened, dive brakes were added, the fuselage was extended and the number of crewmembers was increased to four. As a dive bomber, the Ju 88 was capable of pinpoint deliveries of heavy loads; however, despite all the modifications, dive bombing still proved too stressful for the airframe.With these modifications the top speed had dropped to some 280mph and work was still ongoing with further prototypes being built and no production version or manufacturing in sight.

Again, the Finnish evaluation team liked the aircraft but with prototyping still ongoing and problems being identified in testing, it was a questionable decision. The performance and potential of the prototype however were excellent and the team rated that aircraft highly overall.

Latécoère 298 (France)

The Latécoère 298 (sometimes abridged to Laté 298) was a French seaplane that was designed primarily as a torpedo bomber, but served also as a dive bomber against land and naval targets (with two bombs of up to 150 kg each), and as a maritime reconnaissance aircraft (with extra 535 litre fuel tank), night reconnaissance and smokescreen laying. The design originated in a French Navy requirement for a torpedo bomber to replace the unsuccessful Laté 29 that had just entered service in the mid-1930’s. The prototype Laté 298 was completed at Latécoère’s Toulouse plant in 1936 and first flew on 8 May 1936.

It was designed as a single-engined, mid-wing cantilever monoplane with an all-metal oval-section stressed-skin fuselage. The aircraft was powered by an 880 hp Hispano-Suiza 12Y twelve-cylinder liquid-cooled engine and had a crew of three accommodated under a glazed canopy. Two exceptionally large floats were attached to the fuselage by struts, each float containing a fuel tank. A ventral crutch served to accommodate different payloads, depending on the mission. It could carry one Type 1926 DA torpedo, two 150 kg bombs or depth charges. Additional armament consisted of three 7.5 mm Darne machine guns, two fixed forward firing and one rear-firing on a flexible mount at the rear of the crew canopy. It was sturdy and reliable, possessing good maneuverability.

The Latécoère 298 as evaluated by the Ilmavoimat in early 1938 had a Crew of 3 and was powered by a single Hispano-Suiza 12Ycrs liquid-cooled V-12 of 880 hp giving a maximum speed of 167mph and a range of 497 miles with maximum payload. The service ceiling was 21,325 ft and defensive armament consisted of two fixed forward firing machineguns and one rear-firing machinegun on a flexible mount. A maximum bombload of 1,500lbs, or one torpedo, could be carried.

OTL Notes: The first Laté 298s entered service in October 1938 with the Escadrilles (squadrons) of the Aéronautique Navale, the French Naval Air Force. The first naval escadrilles to equip with the type were T2 at the Saint-Raphael Naval Base and T1 at the Berre Naval Base in February and March 1939 respectively. Escadrilles HB1 and HB2 on the seaplane carrier Commandant Teste re-equipped with the Late 298B in April and July of 1939. In all some 110 Late 298 of all versions had been built by 25 June 1940 and a further 20 Late 298F (with MAC instead of Darne weapons and two additional 7.7mm machine-guns for ventral ‘under-tail’ defence) were built for the French Vichy regime. The Late 298B version had folding wings for shipboard stowage. The Late 298D had a fourth crew member, and the ‘one-off’ unsuccessful Late 298E had a ventral observation gondola.

At the outbreak of WW2 four squadrons flew with this aircraft, and by May 1940, when the German offensive in the west began, 81 aircraft equipped six squadrons. They were used at first for maritime patrol and anti-submarine duties, but did not meet any German ships. The Laté 298s first saw action during the Battle of France in 1940, being used in shallow dive-bombing attacks during the May-June 1940 ‘Blitzkrieg’ on France and later, as the Wehrmacht drove through France, they were used to harass and interdict armoured columns. Despite not having been designed for this role, they performed reasonably well, suffering fewer losses than units equipped with other types. After the armistice of June 1940, the French Navy under the Vichy regime was allowed to retain some Laté 298 units, and several captured aircraft were used by the Luftwaffe for liason duties. Both the Vichy and Free French forces continued to operate the aircraft, mainly on reconnaissance missions.

After Operation Torch, French units in Africa sided with the Allies. In this guise, the Laté 298 was used for Coastal Command missions in North Africa, in cooperation with Royal Air Force Wellingtons. The Laté 298’s final combat missions were flown during the liberation of France, where they were used to attack German shipping operating from strongholds on the Atlantic coast. A number of Late 298’s continued to operate into the post-World War II period with the French Aéronautique Navale, retiring from active service in 1946 but continuing to serve as trainers until 1950.

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero (“Sparrowhawk”) (Italy)

The SM.79 project began in Italy in 1934, where the aircraft was first conceived as a fast, eight-passenger transport capable of being used in air-racing (the London-Melbourne competition). Piloted by Adriano Bacula, the prototype flew for the first time on 28 September 1934. Originally planned with the 800 hp Isotta-Fraschini Asso XI Ri as a powerplant, the aircraft reverted to the less powerful 590 hp Piaggio P.IX RC.40 Stella (a license-produced Bristol Jupiter and the basis of many Piaggio engines). The engines were subsequently replaced by Alfa Romeo 125 RC.35s (license-produced Bristol Pegasus).

The SM.79 had three engines, with a retractable tailwheel undercarriage and featured a mixed-material construction, with a box-section rear fuselage and semi-elliptical tail. Like many Italian aircraft of the time, the fuselage of the SM.79 was made of a welded tubular steel frame and covered with duralumin forward, duralumin and plywood over the top, and fabric on all other surfaces. As with most cantilevered low-wing monoplanes, the wings were of all-wood construction, with the trailing edge flaps and leading edge slats (Handley-Page type) to offset its relatively small size. The internal structure was made of three spars, linked with cantilevers and a skin of plywood. The wing had a dihedral of 2° 15′. Ailerons were capable of rotating through +13/-26°, and were used together with the flaps in low-speed flight and in takeoff. The grouping of engines, the slim fuselage, coupled with a low and wide cockpit and the “hump” gave this aircraft an aggressive and powerful appearance. Its capabilities were significant with over 2,300 hp available and a high wing loading that gave it characteristics not dissimilar to a large fighter.

The engines fitted to the main bomber version were three 582 kW (780 hp) Alfa Romeo 126 RC.34 radials, equipped with variable pitch, all-metal three-blade propellers. Speeds attained were around 260mph at 12,000 feet, with a relatively low practical ceiling of 23,400 feet m. The best cruise speed was at 60% of power. The landing was characterized by a 125 mph final approach with the slats extended, slowing to 90mph with extension of flaps, and finally the run over the field with only 600 feet needed to land. With full power available and flaps set for takeoff, the SM.79 could be airborne within 900 feet then climb to 12,000 feet in 13 minutes 2 seconds. The bomber version had ten fuel tanks (3,460 l).The endurance at full load averaging 200mph was 4 hr 30 min. In every case, the range (not endurance) with a 1,000 kg payload was around 5-600 miles.

The aircraft crew complement was either five or six in the bomber version with cockpit accommodation for two pilots, sitting side-by-side. Instrumentation in the central panel included oil and fuel gauges, altimeter for low and high altitude (1,000 m and 8,000 m), clock, airspeed and vertical speed indicator, gyroscope, compass, artificial horizon, turn and bank indicator, rev counters and throttles for all three engines. Cockpit equipment also included the flight controls, fire extinguishers, and control mechanisms for the brakes and other systems.

The SM.79’s defensive armament consisted of four, and later five machineguns. Three were 12.7 mm (0.5 inch) calibre guns, two of which were in the “hump,” with the forward one (with 300 cartridges) fixed with an elevation of 15°, and the other manoeuvrable with 60° pivotal movement in the horizontal, and 0-70° in the vertical planes. The amount of ammunition was 500 cartridges (in two metal boxes), as was the third 12.7 mm machine gun, located ventrally. There was also a 7.7 mm (0.303 inch) machinegun fitted laterally, with a mount that allowed a rapid change of side for the weapon. This Lewis gun was later replaced by two 7.7 mm Bredas, which were more reliable and faster firing (900 rounds/min instead of 500), even though there was only sufficient room in the fuselage for one man to operate them. Despite the low overall power (Rate of Fire and energy of the projectile) of the SM.79’s machine guns, it was heavily-armed by 1930s standards (for bombers, essentially three light machine guns), the armament being more than a match for the lightly-protected fighter aircraft of the time, not usually fitted with any armour.

The internal bomb bay was configured to carry bombs vertically, preventing larger bombs being accommodated internally. The aircraft could hold two x 500 kg, five x 250 kg, 12 x 100 kg or 50 kg bombs, or hundreds of bomblets. The bombardier, with an 85° forward field of view, had a “Jozza-2” aiming system and a series of bomb-release mechanisms. The machine gun to the rear of the gondola prevented the bombardier from lying in a prone position, and as a result, the bombardier was provided with gambali, retractable structures to support his legs while being seated. Torpedoes were carried externally, as were larger bombs. This was only standardized from 1939, when two hardpoints were fitted under the inner wing. Theoretically two torpedoes could be carried, but the performance and the manoeuvrability of the aircraft were so reduced that usually only one was used in action. In addition, the SM.79’s overall payload of 3,800 kg prevented it carrying 1,600-1,860 kg of bombs without a noticeable reduction of the fuel load (approximately 2,400 kg, when full).

The introduction of the aircraft in operational service was made with 12° Stormo (Wing), starting in early 1936. 12° Stormo was involved in the initial evaluation of the bomber, which continued throughout 1936. The Wing was operational on 1 May 1936 with the SM.79 successfully completing torpedo launches from 5,000 meters in August 1936. The torpedo-bomber variant was much more unstable and less easy to control than the civilian version. Its capabilities were still being explored when the Spanish Civil War broke out, and a number of SM.79s were dispatched to support the Nationalists. By 4 November 1936 there were six SM.79s with crew to fly them operating in Spain and serving with the Aviazione Legionaria, an Italian unit sent to assist Franco’s Nationalist forces during the Spanish Civil War. By the beginning of 1937 there were 15 SM.79s in total, and they went on to be used in Spain throughout the conflict, with very few losses. Around 19 of the total sent there were lost. Unofficially, the deliveries to 12 Wing and other units involved numbered at least 99 aircraft.

The first recorded interception of an SM.79 formation took place on 11 October 1937 when three aircraft were attacked by 12 Polikarpov I-16s (known as the Mosca (Fly) to the Spanish Republicans and Rata (Rat) to the Spanish Nationalists). One of the SM.79s was damaged by repeated attacks made by the slightly faster I-16s, but its defences prevented the attackers from pressing close-in attacks. All the bombers returned to base, although one had been hit by 27 bullets, many hitting the fuel tanks. A few other examples of similar interceptions occurred in this conflict, without any SM.79s being lost. Combat experiences revealed some deficiencies in the SM.79: the lack of oxygen at high altitudes, instability, vibrations experienced at speeds over 400 km/h and other problems were encountered and sometimes solved. Initially the SM.79s operated from the Balearic Islands and later from mainland Spain. Hundreds of missions were performed in a wide range of different roles against Republican targets. No Fiat CR.32s were needed to escort the SM.79s, partly because the biplane fighters were too slow.

OTL Note: After serving in the Spanish Civil War, the Sparviero was brought into use with 111° and 8° Stormo. By the end of 1939, there were 388 Sparvieros in service, with 11 wings that were partially or totally made up of this aircraft. They also participated in the occupation of Albania in autumn 1939. Thanks to the experience gained in Spain, the SM.79-II formed the backbone of the Italian bomber force during World War II and by the beginning of WW2 612 aircraft had been delivered, making the Sparviero the most numerous aircraft in the Regia Aereonautica. These aircraft were deployed in every theatre of war in which the Italians fought. Favorable reports of its reliability and performance during the Spanish Civil War led Yugoslavia to order 45 aircraft generally similar to the SM.79-I variant in 1938, and these Yugoslavian versions were designated the SM.79K. They were delivered to Yugoslavia in 1939, but most were destroyed in the invasion by Germany in 1941 by their crew or advancing Italian forces. Among several actions against German and Italian forces they manage to destroy enemy in Kacanicka sutjeska (Kacanik canyon). Some of aircraft also escaped into Grecce carried King Peter Karadjordjevic and his party. A few did survive, one to be pressed into service with the pro-Axis forces of the NDH, apart from four which became AX702-705 of the RAF.

Attempts were also made to gain large-scale export orders, but only three countries finalized contracts, with twin-engined versions being supplied to Brazil (three with 694 kW/930 hp Alfa Romeo 128 RC.18 engines), Iraq (four with 746 kW/1,030 hp Fiat A.80 RC.14 engines), and Romania (24 with 746 kW/1,000 hp Gnome-Rhône Mistral Major 14K engines). Romania later acquired an additional eight aircraft from Italy powered by Junkers Jumo 211Da engines, and these were designated the SM.79JR. They also built a further 72 Jumo powered variants under license.

The Results of the Torpedo Bomber Evaluation Exercise by the Ilmavoimat – mid-1938

Factors involved in making a Decision: Evaluation criteria emphasized good speed, manouverability and range, bombload / torpedo carrying ability and as always, cost and availability (with an emphasis on certainty of delivery and ability of the supplier to complete manufacturing within a reasonable timeframe). Service Ceiling was not considered a major factor as this was intended as a torpedo bomber. Ratings are 5 (excellent), 4(good), 3 (fair), 2 (poor), 1 (inadequate) for each category. Amphibious capability was not considered necessary as the primary theatre of operations would be the Gulf of Finland and the Northern Baltic – with the Aland Islands functioning as an unsinable aircraft carrier in the event of war, thus extending the range southwards considerably (but floatplanes were given a +1 bonus due to flexibility of basing). Twin-engined designs were given a positive weighting of 2 points as, with extended over-water operations there was a better margin of survivability with an engine failure.

Speed

Blackburn Baffin: 136mph: 0

Blohm and Voss Ha 140: 207mph: 2

Douglas TBD Devastator: 206mph: 2

Dornier Do 22: 217mph: 3

Fairey Swordfish: 139mph: 0

Fairey Albacore: 161mph: 1

Fieseler Fi 167: 202mph: 2

Heinkel He 111: 230mph: 3

Heinkel He 115: 203mph: 2

Junkers Ju88: 317mph: 5

Latécoère 298: 167mph: 1

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero: 260mph: 4

Combat Range

Blackburn Baffin: 490 miles: 1

Blohm and Voss Ha 140: 715 miles 3

Douglas TBD Devastator: 535 miles: 2

Dornier Do 22: 1,428 miles: 5

Fairey Swordfish: 546 miles: 2

Fairey Albacore: 930 miles: 4

Fieseler Fi 167: 808 miles: 3

Heinkel He 111: 1,030 miles: 4

Heinkel He 115: 1,305 miles: 5

Junkers Ju88: 1,429 miles: 5

Latécoère 298: 497 miles: 1

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero: 600 miles: 2

Maneouverabilty

Blackburn Baffin: 2

Blohm and Voss Ha 140: 1

Douglas TBD Devastator: 2

Dornier Do 22: 3

Fairey Swordfish: 2

Fairey Albacore: 2

Fieseler Fi 167: 5

Heinkel He 111: 4

Heinkel He 115: 3

Junkers Ju88: 4

Latécoère 298: 3

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero: 5

# of Torpedoes (Bombload was secondary)

Blackburn Baffin: 1 Torpedo: 3

Blohm and Voss Ha 140: 1 Torpedo: 3

Douglas TBD Devastator: 1 Torpedo: 3

Dornier Do 22: 1 Torpedo: 3

Fairey Swordfish: 1 Torpedo: 3

Fairey Albacore: 1 Torpedo: 3

Fieseler Fi 167: 1 Torpedo: 3

Heinkel He 111: 2 Torpedoes: 5

Heinkel He 115: 1 Torpedo: 3

Junkers Ju88: 2 Torpedoes: 5

Latécoère 298: 1 Torpedo: 3

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero: 1 – 2 Torpedoes: 4

Single or Twin Engines (+2 bonus for twin-engined designs)

Blackburn Baffin: 0

Blohm and Voss Ha 140: 2

Douglas TBD Devastator: 0

Dornier Do 22: 0

Fairey Swordfish: 0

Fairey Albacore: 0

Fieseler Fi 167: 0

Heinkel He 111: +2

Heinkel He 115: +2

Junkers Ju88: +2

Latécoère 298: 0

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero: +2

Floatplane or Land-Based (+1 Bonus for Floatplanes)

Blackburn Baffin: 0

Blohm and Voss Ha 140: 1

Douglas TBD Devastator: 0

Dornier Do 22: 1

Fairey Swordfish: 0

Fairey Albacore: 0

Fieseler Fi 167: 0

Heinkel He 111: 0

Heinkel He 115: 1

Junkers Ju88: 0

Latécoère 298: 1

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero: 0

Cost (Lowest Cost = Highest Ranking)

Blackburn Baffin: 2

Blohm and Voss Ha 140: 4

Douglas TBD Devastator: 4

Dornier Do 22: 3

Fairey Swordfish: 2

Fairey Albacore: 3

Fieseler Fi 167: 4

Heinkel He 111: 5

Heinkel He 115: 4

Junkers Ju88: 5

Latécoère 298: 3

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero: 3

Availability

Blackburn Baffin: 4

Blohm and Voss Ha 140: 4

Douglas TBD Devastator: 3

Dornier Do 22: 4

Fairey Swordfish: 4

Fairey Albacore: 0

Fieseler Fi 167: 4

Heinkel He 111: 5

Heinkel He 115: 5

Junkers Ju88: 3

Latécoère 298: 1

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero: 5

Overall Points Scored and Ranking (maxium possible = 33):

Blackburn Baffin: 12

Fairey Swordfish: 13

Fairey Albacore: 13

Latécoère 298: 13

Douglas TBD Devastator: 16

Blohm and Voss Ha 140: 20

Fieseler Fi 167: 21

Dornier Do 22: 22

Heinkel He 115: 25

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero: 25

Heinkel He 111: 28

Junkers Ju88: 29

At this stage, with the evaluations and test flights completed and initial rankings made, a number of aircraft could immediately be eliminated. As can be seen, the performance of the British and French aircraft in terms of speed and range were so poor that they were removed from consideration. Indeed, the evaluation team (as was mentioned) raised concerns with the British that when compared to other countries aircraft and designs, their torpedo bombers were so out-dated that they would almost certainly be wiped out of the sky if faced with any serious opposition. The Douglas Devastator was briefly considered but, put simply, the German and Italian aircraft were so far in advance of the Devastator that after a brief assessment, this was also eliminated. The handling of the Bloehm abd Voss Ha 140 had been so poor in the test flighst that this aircraft also was eliminated immediately.

Of the remaining aircraft, the Fieseler Fi 167 was considered for a longer period – it was a highly maneouverable aircraft, superb in fact, and it remained in the running due to this. In the end though, the decision boiled down to the three aircraft with the highest speed and bomb or torpedo load / armament capacity. The superb track record of the SM 79 in the Spanish Civil War was a consideration, as also was the performance of the He 111 in the samwe conflict. At this stage the SM 79 was tentatively eliminated – its somewhat limited range being the primary factor, and the finalists then boiled down to the Heinkel He 111 and the Junkers Ju88 with the SM 79 and Fi 167 as runners up. There were major concerns about whether the Junkers Ju88 would move into production, but in the end these conerns were outweighed by the performance of the aircraft. Initial discussions with Junkers took place, and as it turned out, both Junkers and the Reichsluftfahrtministerium saw an opportunity to use the Maavoimat as guineapigs to further test the aircraft. At the time of the early negotiations, Dr. Heinrich Koppenberg (managing director of Jumo) assured the Finnish Team that the production of 300 Ju 88s per month was definitely possible and that the Finnish order would easily be filled.

The Merivoimat ordered 24 Junkers Ju88’s, modified to be able to carry torpedoes and with a longer wingspan to correct performance deficiencies that the Merivoimat evaluation team had identified in their testing. The aircraft could also be used as bombers and as dive-bombers and could carry a maximum bombload of 5,510 lbs (although in practice it was usually between 3,000 and 4,500 lbs). Again, as with some of their other bombers, the Finns specified a solid nose, in this case with provision for mounting four Finnish-manufactured 20mm Hispano Suiza cannon in the nose (After the aircraft were delivered to Finland, many of the aircraft were fitted with a further four 20mm cannon in twin blisters on either side of the fuselage. This reduced performance a little but the pilots preferred to have the additional fire power for suppression of AA fire when attacking at low level. In action, the impact of 8 streams of 20mm cannon shells on a destroyer had to be seen to be believed). As the Finnish aircraft were intended to be used almost exclusively for low-level torpedo attacks, the ventral weapon (and crew position) was removed – the Merivoimat Ju88 flew with a Crew of 3 (Pilot, Co-Pilot/Navigator and Rear Dorsal Gunner).

The decision having been made, Finland negotiated with Junkers and the Reichsluftfahrtministerium through July and August of 1938 while at the same time keeping the doors open with Heinkel and the Italians in the event that the Junkers purchase could not be finalised. However, in early September 1938 the deal was finally signed and closed, although there were some concerns over the delivery timelines. The Munich Crisis accentuated these concerns, as did the developmental problems that Junkers continued to experience which slowed production to a painfully slow pace which caused the Finns great concern, to the extent that they consider cancelling the order and buying either the Heinkel He 111 or the SM 79 instead.

By January 1939, one Ju88 per week was beginning to trickle off the Junkers production line, but as problems were ironed out this began to improve and the Merivoimat took delivery of the final aircraft of the order in July 1939, shortly before the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact shocked the world, and the details of the secret clauses relating to Finland and the Baltic States shocked the Finnish Government and military.

With a far higher maximum speed than the old Ripons, new tactics suitable for the Junkers Ju88 needed to be developed and rehearsed. The aircraft was capable of a relatively quick climb, had an excellent turn-of-speed for its time, and its rugged structure and responsiveness allowed the aircraft be flown to the maximum capabilities of its flight envelope. The best means of defence from fighters, however, was to fly in tight formations down at sea level. Utilizing flaps and slats, takeoffs and landings could be performed in short distances, making it suitable for use on rough airfields. Torpedoes could be carried on two hardpoints under the inner wings. Finnish-built torpedoes based on a German design were utilised.

The Ju88 had several advantages compared to other torpedo-bombers. In mid-1939, it had no equal as a torpedo bomber in speed. The Douglas Devastator for example, with a maximum speed of 206mph was far slower, the other contenders such as the old Fairey Swordfish even more so. While the relative efficiency of torpedo-bombers compared to dive-bombers for attacks on naval targets continued to be debated, the Merivoimat Air Arm opted for both. Dedicated torpedo-bomber squadrons equipped with heavy aircraft were expensive and specialized, but the torpedoes packed a heavy punch if they hit, certainly enough to damage a battleship. Dive-bombers on the other hand were less costly and more flexible, being able to be used against both naval and land targets, used more economic and less specialized weapons, and had a less dangerous flight profile while diving almost vertically from high altitude but the size of the bombs able to be carried meant that were probably less effective against the topsides of well-armoured battleships. It was a debate the Merivoimat resolved to some extent by opting to buy both – and in the event, with the Junkers Ju88 they had an aircraft that could fill both roles – and it was a decision that served them well.

Merivoimat Junkers Ju88 Torpedo bomber following delivery in mid-1939: this was one of the first aircraft delivered and came with the glazed nose: some of the first aircraft were delivered to the Merivoimat without the specified solid-nose modifications….In service, the Ju88 proved to have good flight performance and was highly manoueverable, with excellent cockpit visibility for the Pilot.

As the Finnish aircraft were intended to be used almost exclusively for torpedo attacks, the ventral weapon was removed. Additionally, the intended use of the Ju 88 by the Merivoimat Air Arm in low-level attacks (as a torpedo-bomber), meant that the aircraft would likely be attacked almost exclusively from the rear and above and this was one of the two main concerns – and was met up upgrading the rear gunners position to twin machineguns. The other was the equipping of the aircraft with forward-firing guns of a heavy calibre for flak suppression during torpedo attacks. To achieve this, four Hispano-Suiza 20mm cannon were mounted in the fuselage nose, with an additional four in blisters on the fuselage on each side of, and below, the cockpit.

Following the virtual elimination of the Soviet Baltic Fleet early in the Winter War, Merivoimat Ju88’s were used heavily in support of the Maavoimat over the Spring and Summer of 1940. They proved as effective in this role as they had as torpedo bombers. With engine upgrades, they remained in service into the 1950’s.

OTL Note: The Ilmavoimat actually did have Ju88’s. In April 1943, as Finland was fighting its Continuation War against the USSR, the Finnish Air Force bought 24 Ju 88s from Germany. The aircraft were used to equip No. 44 Sqn which had previously operated Bristol Blenheims, but these were instead transferred to No. 42 Sqn. Due to the complexity of the Ju 88, most of 1943 was used for training the crews on the aircraft, and only a handful of bombing missions were undertaken. The most notable was a raid on the Lehto partisan village on 20 August 1943 (in which the whole squadron participated), and a raid on the Lavansaari air field (leaving seven Ju 88 damaged from forced landing in inclement weather). In the summer of 1943, the Finns noted stress damage on the wings. This had occurred when the aircraft were used in dive bombing. Restrictions followed: the dive brakes were removed and it was only allowed to dive at a 45-degree angle (compared to 60-80 degrees previously). In this way, they tried to spare the aircraft from unnecessary wear.

One of the more remarkable missions was a bombing raid on 9 March 1944 against Soviet Long Range Aviation bases near Leningrad, when the Finnish aircraft, including Ju 88s, followed Soviet bombers returning from a night raid on Tallinn, catching the Soviets unprepared and destroying many Soviet bombers and their fuel reserves, and a raid against the Aerosan base at Petsnajoki on 22 March 1944. The whole bomber regiment took part in the defence against the Soviets during the fourth strategic offensive. All aircraft flew several missions per day, day and night, when the weather permitted. No. 44 Sqn was subordinated Lentoryhmä Sarko during the Lapland War (now against Germany), and the Ju 88s were used both for reconnaissance and bombing. The targets were mostly vehicle columns. Reconnaissance flights were also made over northern Norway. The last war mission was flown on 4 April 1945. After the wars, Finland was prohibited from using bomber aircraft with internal bomb stores. Consequently, the Finnish Ju 88s were used for training until 1948. The aircraft were then scrapped over the following years. No Finnish Ju 88s have survived, but an engine is on display at the Central Finland Aviation Museum, and the structure of a German Ju 88 cockpit hood is preserved at the Finnish Aviation Museum in Vantaa.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

One Response to The Torpedo Bomber Purchase of 1938