The Winter War and Australia saw many types of material aid supplied to Finland from two countries, Australia and New Zealand, which had no significant armaments industry to speak of – but which despite this, did their best to support Finland, largely due to significant public pressure on the Goverments of the two countries to “do something.” Aid and assistance for Finland were largely a “bottom up” initiative, as we will see….

The Winter War and Australia

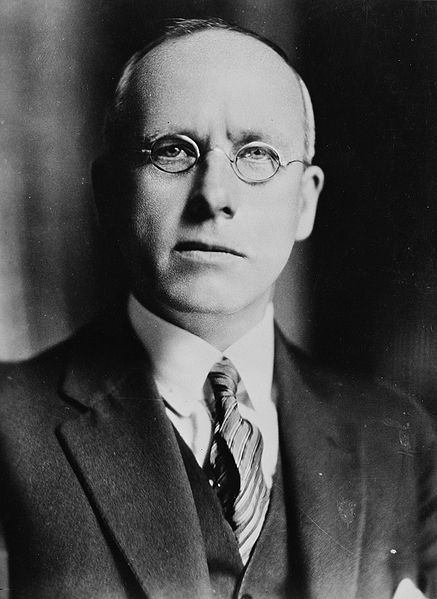

When Britain had declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939 the federal parliament of Australia was sitting in Canberra. The Australian Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, without consulting Parliament, immediately broadcast on national Radio that Britain was at war and therefore that Australia was at war. To Menzies, there was one King, one Flag and one cause, and so almost all Australian people saw it. In those crucial early days of the war, Australian Foreign Policy was directed from the Australian High Commission in London, where the Commonwealth High Commissioners were an essential part of the British policy making machine. All the Dominions had High Commissioners in London. They had begun regular meetings on an informal basis during the period of sanctions against Italy. These meetings had assumed a definite shape and greater importance during the Munich crisis, and by the time WW2 broke out the High Commissioners were meeting once a day with the British Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs in a consultation among relative equals.

As has been mentioned earlier, Australia’s High Commissioner in London was S M Bruce, former Prime Minister of Australia and Minister for External Affairs from 1923-1929, who had been High Commissioner since 1933. A polished Anglophile, confidante of Sir Alexander Cadogan (Permanent Under Secretary of the Foreign Office, 1938-1946), Bruce ostensibly reported to Sir Henry Gullet, Australia’s Minister for External Affairs from 26 April 1939. But because as High Commissioner Bruce was such a distinguished incumbent, Gullet made little contribution to policy making within the Australian External Affairs Department. The Euro-centered concepts of Australian foreign policy were further developed because of the way in which the contribution of the Commonwealth was crucial to the British War Effort. The strategic importance of the Commonwealth resulted in heavy weight being given to the counsels of the Commonwealths elder statesmen: Bruce, General Jan Smuts (South African Prime Minister and Minister for External Affairs and Defence, 1939-1948), Sir Earl Page (Australias Special Envoy to the War Cabinet), and Richard Casey (leader of the Australian delegation to the meeting of the United Kingdom and Dominions Ministers, October-December 1939, and subsequently a member of the United Kingdom War Cabinet).

With Neville Chamberlain (and later Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden) relying on the advice of the Commonwealth Ministers in London, it was scarcely to be wondered at that the external affairs office in Canberra took a low profile. In London, Bruce had been peripherally aware of the growing tensions between the USSR and Finland but had paid little attention to the situation until the Soviet Union actually attacked Finland. The Finnish Ambassador in London, Gripenberg, had of course met with Bruce on a number of occasions but with little success in terms of gaining any support from Australia. Bruce was reluctant to involve Australia in what he saw as a sideshow of little relevance to Australia and this was the basis of his advice back to Australia. Nevertheless, events in Australia had by this time begun to overtake Bruce. Much to his dismay, it seemed that public opinion in Australia was forcing an intervention that he did not see as being in Australia’s interests. The very public commitment to Finland of a volunteer battalion by the New Zealand High Commissioner in London was strongly opposed in private by Bruce, and it was only reluctantly that he acquiesced to instructions from Canberra to assist the New Zealanders in their endeavours.

Back in Australia, events had gathered their own momentum from early November 1939 on, assisted by the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Team. The new Finnish Consul, Paavo Simelius had been working non-stop to secure introductions for the 20 man Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Team, some of whom were in turn working furiously with Australian journalists and advertising companies to put out material supportive of Finland. Elsewhere, members of the team, including the Rev. Kurkiala and Jorma Pohjanpalo were establishing their own contacts in the religious, political and business fields. At one and the same time, Sydney’s Finnish community was preparing for the worst and organizing, whilst at the same time praying that there would be no war. Simelius had indeed secured an appointment with the Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, in mid-November 1939 as Finland girded for war. Menzies was non-committal at this time, advising Simelius that if Finland was attacked, there would be little that Australia could do beyond providing moral support. The Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Team thought otherwise, although few concrete steps were taken prior to the actual outbreak of war. Nobody wanted to be premature.

On the 30th of November, 1939, the Soviet Union attacked Finland with no declaration of war. The Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus team in Sydney was prepared. Along with the front page headlines were a continuous stream of background articles filling the Australians newspapers, describing Finland, setting out the situation, providing a background to the unprovoked attack on a small neutral country which wished only to remain at peace, suggesting ways in which Australians could assist Finland. The immediate Australian public reaction was one of indignation and condemnation of the USSR’s actions. Editorials stridently critical of the USSR blazed across every newspaper in the country. Well-prepared and prominent supporters of Finland spoke on the radio and seemingly overnight, the Australian Finland Assistance Organisation emerged, announced on the 3rd of December 1939 at a packed public meeting in Sydney where the prominent speakers included the joint founders (whom we will cover in the next Post), Dr Lewis Windermere Nott and Colonel Eric Campbell together with the Rev. Kalervo Kurkiala.

The inaugural meeting of the Australian Finland Assistance Organization in Sydney on the 3rd of December 1939 was packed to capacity.

Within days, branches of the Australian Finland Assistance Organization had been established across Australia, with offices prominently positioned in main streets. Churches, factories, schools, Returned Servicemen’s Association Halls, all were pressed into service as popular enthusiasm led to the organisation’s membership soaring into the thousands and then into the tens of thousands within days. Fund-raising activities commenced almost immediately, with Churchs’ taking up Collections for Finland, street corner collectors in the cities and large towns, collections in the factory and the office, fund-raising fetes and, on a larger scale, requests to businesses for donations. Within days, thousands of pounds had been collected, within weeks, tens of thousands as the Australian public responded to the call. By mid-December 1939, it seemed that a large percentage of the Australian population were involved in the campaign to support Finland. It was a cause that stirred enthusiasm in the public, far more so than the war with Germany. And this enthusiasm was in large part the result of the skilful distribution of information, news articles and commentary provided by the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus team.

Buy a Ford for Finland

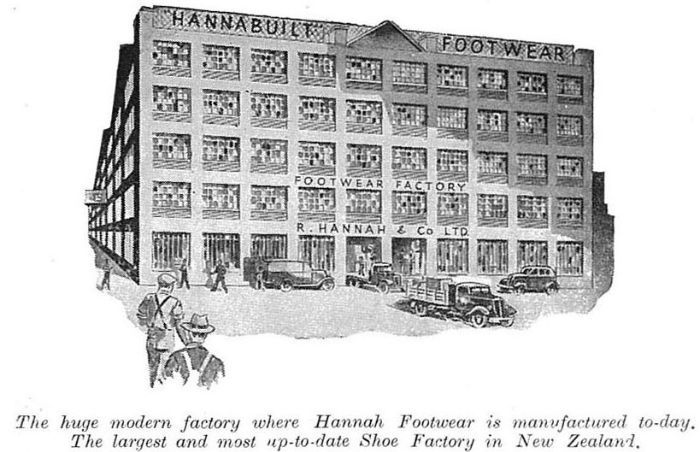

One of the most iconic fund-raising campaigns for Finland in Australia was the “Buy a Ford for Finland” campaign initially kicked off by a Ford dealership in Sydney in mid-December 1939. Ford Australia was the Australian subsidiary of Ford Motor Company and had been founded in Geelong, Victoria in 1925 as an outpost of the Ford Motor Company of Canada, Limited (Ford Canada was a separate company from Ford USA. Henry Ford had granted the manufacturing rights to Ford in the British Commonwealth (excluding the UK) countries to a group of Canadian investors. By the late 1930’s, the Ford Geelong plant was a large scale concern and Ford was one of the two major motor vehicle manufacturers firmly established in Australia (the other was Holden, a formerly Australian owned company which had become a subsidiary of General Motors in 1931 (in 1930, Holden had manufactured 34,000 vehicles, which gives you an idea of the scale of these two companies). During World War II both companies saw their efforts shifted to the construction of military vehicles, field guns, aircraft and engines – but in the period we are concerned with, this shift had not yet begun and orders for military vehicles had not been placed with either company.

In December 1939, prior to the decision being announced that the Australian Government would support the sending of volunteers to Finland, Ford Australia very publicly donated outright 50 Ford trucks for use as Ambulances, with the fitting out as specialist Ambulance trucks being carried out by Ford workers on a voluntary basis. Such was the enormous goodwill that this announcement generated for Ford that a Ford dealer in Sydney who was strongly sympathetic to the Finland Assistance Organisation’s efforts announced that he would donate the profits for every Ford vehicle sold over the months of December and January to the Organisation. The Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Information Team in Sydney used the networks they had established to ensure the announcement gained widespread publicity and the Ford Dealer saw his sales soar within days. At the same time, a bright spark within the Tiedotuskeskus Information Team suggested to the Organisation that they establish their own “Buy a Ford for Finland” fund raising campaign. The concept took off like an Australian bushfire, sweeping the country. Finland Assistance Organisation speakers, news articles and radio broadcasts praised the idea. This was something tangible that Australia could contribute, something that would assist the soldiers of Finland in their fight, it was something towards which every Australian’s contribution, no matter how small, counted.

Ford Australia saw an advertising campaign that would gain them widespread name recognition in the unrelenting competition with Holden, even then somewhat of an Australian icon. Determined to milk this for all it was worth, Ford Australia almost immediately announced that all Ford vehicles purchased for dispatch to Finland would be passed on at cost, while the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union announced that their members at the Ford Plant would contribute their own time to any specialist fitting out needed for military use of the Ford trucks. The campaign swept across Australia, with Boy Scouts and Girl Guides conducting “bottle drives,” Church’s passing additional collections on Sundays, volunteers collecting money at factories and on street corners. Almost every city and town in Australia worked to purchase a Ford Truck, graphic displays tracked the funds raised and the numbers of vehicles paid for, news articles reported daily on progress – and Ford’s name was splashed across every newspaper, every day of the week. Articles were written describing how Ford Trucks were used in an Army Division, Ford Trucks were on display across the country, photos of Ford Trucks were plastered across every newspaper in the country on a regular basis. For Ford, it was name recognition beyond all expectations – and within the first week, sufficient money had been raised to pay for almost 250 of the Ford 4×4 trucks.

A procession of Ford 4×4 Ambulance Trucks heading to Melbourne from the Ford Geelong plant. The Ford 4×4 ambulance did little for patient comfort during evacuation, but they were among the best available within the technology of cross-country trucks at the time.

In January 1940, in tandem with the announcement that the Government would support the sending of a Volunteer Force to Finland, the Government also committed to ensuring all vehicles purchased were shipped to Finland together with the Volunteers. The campaign continued, with the target set at 3,500 Trucks – the transport establishment for a British Army Division (which in point of fact was far in excess of that allocated to a Maavoimat Division). By the end of December 1939, the fund-raising campaign had paid for 1200 Ford trucks. By the end of January 1940, with the Ford Geelong Plant now working to full capacity, some 4,200 Ford Trucks had been paid for, manufactured, crated and were in Melbourne being loaded for shipment to Finland together with the Australian Volunteers. General Motors in Australia had also, and somewhat belatedly, sprung into the act with their own campaign, but unfortunately for them, they failed to come up with a marketing slogan as catchy as Ford’s. Nevertheless, some 250 Holden-manufactured half ton 4×4 truck’s were bought and crated for shipping to Finland together with the Volunteers. On use in the Winter War, the Holden 4×4 trucks became synonymous with a rugged durability that only the Sisu-trucks manufactured in Finland rivaled. Vehicle manufacturing for Finland would end with the dispatch of the convoy of ships to Finland in early February 1940, but both Ford and Holden would continue working to meet newly placed orders from the Australian Government. The Finland campaign had actually been beneficial for both companies in that it had allowed them to re-hire (or hire and train) additional workers and move, at least in Ford’s case, to full production so that when Government orders were placed, these could be met rather more quickly than might have been the case.

With the startling success of the “Buy a Ford for Finland” campaign, Holden belatedly got into the game with the “Support Finland with a Holden” campaign.

Photo at left: Australian-supplied Holden 4×4 Ambulance in use by the Polish 1st Corps during the Winter War (Karelian Isthmus, Summer of 1940). Note the driver is a Polish woman volunteer. A considerable number of Polish women had escaped to Finland via Lithuania and Latvia and many had joined the Polish Army in Finland. The Polish Divisions in Finland were created on the Maavoimat model and Polish women filled numerous rear-echelon positions.

There were of course other fund raising campaigns. The announcement that volunteers were being dispatched aroused the patriotic fervour of the Australian people – and the Australian Finland Assistance Organization found itself flooded with volunteers and donations of money and materials, with the Australian Government belatedly stating that all public contributions would be matched by the Government on a 1 for 1 basis (although in point of fact the Government contributed rather more as they committed to paying outright for all travel costs, the provision of uniforms and basic military equipment as well as paying an allowance to the Volunteers – which were in fact the majority of the costs). The Australian Pharmaceutical and Medical Supplies industry provided large quantities of medical and pharmaceutical supplies at cost and these were transported to Melbourne by the State Railways free of charge where they were sorted and packed by volunteers. In addition to the ships transporting the 5,000 odd Volunteers and accompanying military and medical cargo, half a dozen shiploads of Australian wheat donated outright by the Australian Wheat Board (in the late 1930’s wheat was fast becoming Australia’s single most valuable agricultural export item) with the proviso that Finland arrange for shipping.

Not only wheat was shipped. Australia was a large exporter of various agricultural products, as was New Zealand. Both countries exported frozen mutton and lamb as well as significant quantities of dairy products. In addition, both countries had a widespread canning industry with large canning plants putting out a wide variety of products – canned meats, jams, fruits, vegetables, the significance of which we often forget in these days when so much is refrigerated. Keeping in mind that with the bulk of Finland’s manpower mobilized in the military, along with many women likewise – and many more working in factories on the production of war material – and with most farm vehicles and the majority of farm horses also mobilized – Finland expected to experience a major food-production crisis in the event of a drawn out war. Another concern that arose was with the arrival of significant volunteer forces in Finland – as the Italians, Spanish, Hungarian and Scandinavian Divisions arrived – and with 25,000 Poles already in the country – and Commonwealth units en route – the Maavoimat was being augmented not just by 100,000 foreign volunteers, but by 100,000 attached mouths and digestive systems that required feeding. Given that the population of Finland was only three and a half million, and stockpiled food supplies were barely sufficient for that number, one hundred thousand additional bodies was a significant number to cater for. The provision of sufficient additional food supplies was a problem that had been fairly low on the original priority list for the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Teams, but this changed rapidly (Food supplies would be a problem that would escalate further in the summer of 1940 with the flood of Estonian refugees from Tallinn, and again after the end of the Winter War with the influx of Karelians and Ingrians. Fortunately, the pre-war introduction of potato and pig farming in Lapland went some way towards alleviating potential food shortages – and the ability to import food from Australia, Canada and the United States on ships of the Finnish merchant marine and through the port of Lyngenfjiord through the war years prevented any shortage of food developing. Indeed, during the Siege of Leningrad by the Germans, the Finns would permit trainloads of food to cross the border into the USSR to supply Leningrad, although there was considerable and very heated internal debate within Parliament before this was permitted).

Immediately prior to the Christmas of 1939, the Sydney Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Team worked with the Finland Assistance Organisation to put together a “Donate Food for Finland” campaign. This too was a campaign in which every individual, even school children, could participate – and the Christmas Season saw the campaign get off to a flying start. And this was a campaign that rapidly spread to New Zealand as well. It seemed that every Grocers, Co-op and Department Store across Australia and New Zealand had a large collection box labeled “Food for the Soldiers and People of Finland” plastered across it. Schools and Churches organized their own campaigns. The Finland Assistance Organisation borrowed space from Churches, Stock Agents, Warehouses – wherever this could be obtained at no cost – to act as collection depots, where volunteers sorted donations by type, boxed and crated items and organized shipment by Rail to the Warehouses and Melbourne. Day after day, wagonload after wagonload of food poured into the Melbourne warehouses from all across Australia, where warehouses fast being packed to capacity awaited the rapidly approaching Finnish Merchant Marine cargo ships.

Australian Volunteers from the Country Women’s Association (CWA) at a Finland Assistance Organisation packing boxes to be sent to Finland. Numerous organizations were involved in supporting the Finland Assistance Organisation, but the Country Women’s Association was perhaps the largest and the most dedicated.

The Country Women’s Association in Emerald, Queensland, December 1939. It was small groups such as these spread everywhere across Australia and New Zealand that made the volume of assistance that was in the end provided so significant – and who also generated the political pressure on the Australian Government that ensured Menzie’s somewhat reluctant acquiescence to the dispatch of the Australian Volunteers to fight.

And it was in small grocery stores such as this, spread throughout both Australia and New Zealand, that canned food for Finland was collected, a trickle of donations becoming a flood – and eventually enough to fill a number of Finnish cargo ships to capacity. In this way, some interesting Australasian delicacies found their way to Finland – some to be enjoyed, some not. As the war progressed and food shipments from Australia and New Zealand were organized on a more regular basis, Maavoimat soldiers could never be quite sure what their next meal would consist of…….

From New Zealand, “K” brand plum jam was one of the most common “jam” items sent to Finland by the pallet load (and incidentally, was one of the most popular product lines within New Zealand – sadly, the company shut up shop at the beginning of the 1970’s after ninety years in business but the plum jam was great!)

The manufacturers themselves began advertising, promoting products to be bought for shipment to Finland. “Recommend “K” Peach Jam – the best variety to include in Parcels for Finland”. And so, Maavoimat soldiers would end up with a lunch of Rye Bread with New Zealand Cheese and Peach or Plum Jam

The manufacturers themselves began advertising, promoting products to be bought for shipment to Finland. “Recommend “K” Peach Jam – the best variety to include in Parcels for Finland”. And so, Maavoimat soldiers would end up with a lunch of Rye Bread with New Zealand Cheese and Peach or Plum Jam

George Allen and staff in the Dominion Road Four Square store, Auckland, New Zealand with the items stacked on the counter and floor being a single day’s worth of donations to the Food for Finland Campaign made by customers.

Packing sheep’s tongues into tins for shipment to Finland – at Irvine & Stevenson’s St George Co. Ltd plant in January 1940

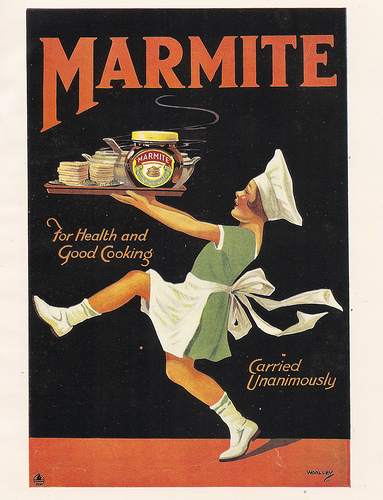

There was of course a far wider variety of food donated than that shown above. In addition to wheat, canned meats, jams and staples such as Spag Cheese, honey, cheese, canned fruit and vegetables and fish, baked beans, vegetable soups, pork and beans, were also sent. Some of the more exotic donations were canned sheeps tongues, canned loganberries, dessert raspberries, diced fruit salad and even canned Bluff Oysters from the south of New Zealand.Perhaps the most awful of New Zealand exports, large quantities of Marmite were sent to Finland for finnish children. For those who have not had the pleasure, the taste of this so-called “food” is indescribable – although to the unwary it visually rather resembles a chocolate spread. As the manufacturer’s marketing slogan says with complete truth: “Love it or hate it.”

Marmite is a concentrate of yeast extract made as a by-product of beer brewing (and thus available in large quantities in New Zealand, both then and now). Marmite is traditionally eaten as a spread on bread, toast, or crackers and other similar baked products. Owing to its concentrated taste it is usually spread very thinly with butter or margarine. It was recommended for children due to i’s “healthy nature” and large quantities were sent to Finland for finnish children – who did NOT bless their benefactors. (For those interested in sampling this uniquely New Zealand taste sensation, please note that in November 2011, Sanitarium, the NZ manufacturer) shut down the sole production line of New Zealand Marmite at its Christchurch factory after damage from the 2011 Christchurch earthquake and its aftershocks. On 19 March 2012, the company announced that its stocks of Marmite had run out and the production line was not expected to be running again until July. Some supermarkets rab out of stock, leading to the dubbing of the crisis as “Marmageddon”. Immediately after the announcement, panic buying of Marmite took place. Over one hundred auctions for jars of Marmite were listed on NZ online auction site TradeMe, with some sellers asking for up to NZ$800 per jar; over 185 times its usual retail price of around $4.25 per 250g jar.. The NZ Government advised people to use the spread sparingly, with Prime Minister John Key admitting he may have to switch to Australian rival Vegemite once his personal supplies run out. In June 2012, it was announced that additional structural damage had been uncovered at the factory, and the proposed July return to production was pushed out to October.

In addition to the donated food which was generally in small cans, bulk amounts of Rice and Sugar from Queensland were purchased for shipment. The Finland Assistance Organisation also used a good part of the money donated to purchase large amounts of bulk-canned foods. This consisted primarily of Tinned Mutton, Corned Beef and the ubiquitous cans of kangaroo tail soup, soon to become a frontline delicacy in Finland. Both New Zealand and Australia were large-scale suppliers of Mutton and Lamb for the export market, although even in the inter-war years the bulk of this export trade was in frozen meat. However, there were numerous canning plants in existence and it proved fairly straightforward to meet the Canned Meat orders from the Australian Finland Assistance Organisation.

The great advantage of canned meat of course was that it could be shipped without refrigeration and in ordinary cargo ships (refrigerated cargo ships were fairly specialist and the Finnish merchant marine had very few of these). It could also be stored in ordinary warehousing facilities, unlike frozen carcasses which required storage in specialist facilities. Canning plants had been used extensively for these very reasons in WW1, but in the inter-war years, Australian canning plants had deteriorated. Nevertheless, there was sufficient capacity available to process canned meats and soups for shipment to Finland and the canning plants remaining welcomed the business, even at cost. Remembering WW1, the Australian Government initiated follow-on orders for the canning plants which were taken up as the initial production for Finland came to an end.

Kangaroo Tail Soup (or Stew) was something of an unknown outside Australia, but the vast numbers of pestiferous kangaroos were in fact rather tasty and made a most acceptable stew. They were also more or less free – and in rural areas, there was a sudden surge in Roo hunting as the Food for Finland campaign suggested that any good patriotic Aussie who wanted to support the people of Finland should go out and plug a few Roo’s on a Saturday and bring ‘em back into town where the local butcher could quickly process them for the local canning plant to utilize.

And since shooting kangaroos was a popular pastime, the popularity of this activity was high in country districts. One could sit down for a beer at the pub or the RSA on a Saturday evening and when asked what you’d done, you could genuinely say you’d been out working for the Finland Assistance Organisation. With a grin. There was an added benefit in that the hides from the slaughtered kangaroos made superb leather.

The ubiquitous kangaroo tail soup, soon to become a frontline delicacy in Finland. Australia would ship enormous quantities of canned kangaroo tail soup to Finland (although if one was honest, one would say the main ingredient was chunks of kangaroo steak, rather than the tails which are rather boney appendages). Since kangaroos ran wild by the millions in Australia, the cost of the main ingredient was low. That said, most of the millions of cans of kangaroo tail soup would find its way to the soldiers on the frontlines, of whom many, it must be said in all honesty, DID acquire a taste for this marsupial delight – an indication of an affinity for Australian products among Finns which can still be seen in Helsinki today with its plethora of Australia-themed bars. Stockpiles of kangaroo tail soup would still exist in military warehouses at the end of WW2 – most of these were used up by the Lotta Svard organization in their relief work in the immediate post-WW2 years in the Baltic States, Poland and northern Germany. As one Finnish soldier was quoted as saying in an Australian newspaper – “it sure tastes better than Squirrel Stew….”

The Ingredients of a typical Can of Kangaroo Tail Soup as supplied to Finland included:

1 kilo (2 pounds) of kangaroo meat, diced

4 rashers of fatty bacon cut into large pieces

2 large onions diced, 2 large carrots diced, 4 medium potatoes cubed

50grams green peas, 4 cloves garlic, finely chopped

1 tablespoon butter, pepper and salt

1 tablespoon flour, 2 tablespoon tomato sauce, 1 dessertspoon Worcestershire sauce

To make the Soup prior to canning, the diced kangaroo was lightly fried in butter for 10 min, add diced onions, garlic, bacon, pepper and salt. It was then fried for another 10 min after which pre-cooked vegetables were added and simmered for 30 minutes before stirring on flour and water, then adding tomato sauce and Worcestershire sauce. As issued by the Maavoimat to Field Kitchens in the Winter War (and afterwards) to the horror of conscripts doing their training who had been subjected to the “Kangaroo Soup” horror stories of their fathers and older brothers who had sampled this antipodean delicacy, in many cases continuously for weeks on end, one standard can served two meals. A larger can serving 10 was also supplied in large quantities, generally issued to Field Kitchens.

In this Food for Finland campaign, Australian farmers, meatworks and unions would play a large part, with many farmers donating sheep for slaughter, meatworkers donating their work (an unusual occurrence in Australia but such was the popular support for Finland), the meatworks processing and canning the meat at cost and dockworkers loading Finnish cargo ships in their own time. All told, this was a significant quantity of food and one that would be much appreciated on its arrival in Finland.

Later in the Winter War, the Finnish Government would put the importing of food from Australia, Canada, the USA and South America on a more regular basis, with less reliance on donations and fund-raising, and more on the purchase of needed basics such as wheat, rice and sugar. Nevertheless, Australia could continue to be an important source of agricultural imports for Finland throughout WW2, largely transported on the large Finnish merchant marine which would continue to roam the worlds oceans throughout WW2, earning significant foreign exchange (and losing many ships and crew) for Finland in the process.

The “Uniforms for Finland” campaign

Another area in which Australia made a significant contribution was the “Uniforms for Finland” campaign that the Australian Finland Assistance Organization initiated. One thing both Australia and New Zealand were and are noted for from the early years of settlement was the production of high quality wool. There were a significant number of sheep bred for their wool in both countries – and the sheer volume of wool produced was enormous. In the nineteenth century most of this wool however was exported raw in bales to the UK, where British textiles mills did the processing and manufacturing.

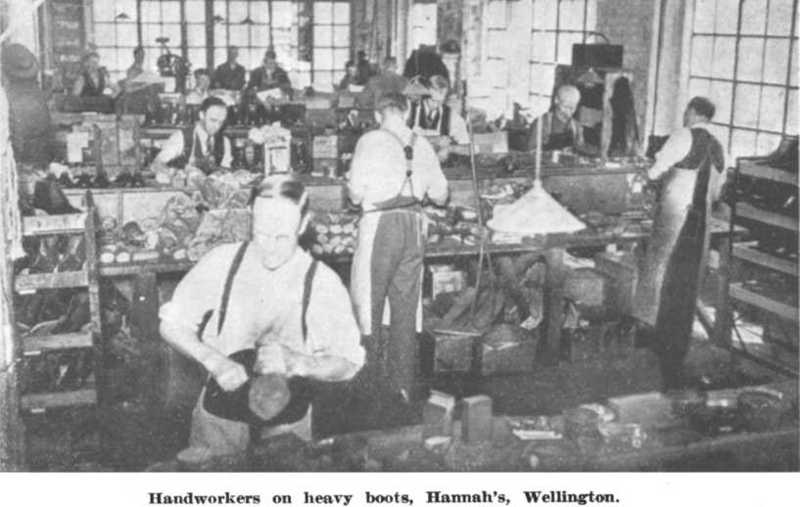

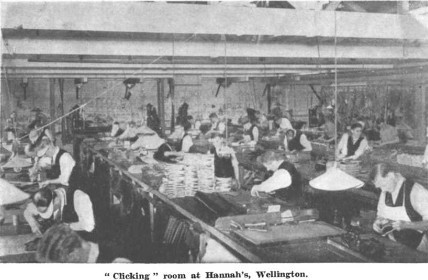

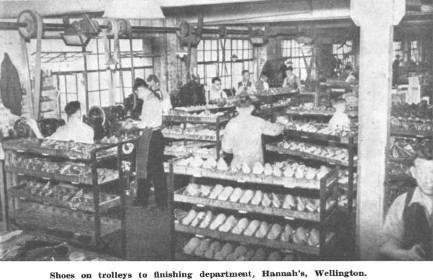

However, by 1909 some 9% of Australian wool clip was used by textile manufactories in Australia and New Zealand was similarly developing a large textile industry. The military requirements of WW1 boosted the industry, with almost all the wool produced during the war years being purchased by the Government At the cessation of hostilities, there remained a vast stockpile of unsold wool, and around 1920, in order to furnish employment for soldiers returning from overseas, the Australian Government took active measures to promote secondary industries, which contributed to the establishment of textile mills in a number of regional centres. The total number of textile and garment manufactories in Australia soon climbed to 4,575.

A typical Australian mill established at the time was Wangaratta Woollen Mills, in Victoria, which was opened in 1922 and produced worsted knitting and weaving yarns by 1923. Confidence in the future was firm and plans to expand the operation by the addition of a scouring, carding and combing plant were being drawn up; this was supplemented by a dyeing and recombing plant in 1930. The cotton and flax sectors of the textile industry had not been idle all the while, and were establishing themselves during the post-war years.

In 1923, in Sydney, George Bond (later Bonds Industries) commenced spinning cotton yarn and began the manufacture of towels and knitted garments and, in 1926, the Airedale Weaving Mills, of Melbourne, began weaving cotton tweeds and engineer’s twist. The latter company pioneered the cotton-weaving industry in Australia which grew rapidly, with a number of different companies setting up factories. Almost without exception, all these companies imported overseas technology.

With the Depression of the 1930’s, the export markets for woolen textiles saw lower demand and the prices sheep farmers earned for raw wool dropped markedly, leading to financial difficulties for many sheep farmers in both Australia and New Zealand. At the same time, stockpiles of wool built up and even as late as 1939, these stockpiles were still substantial. And with approximately 110,000,000 sheep, many of which were Merino’s producing high quality wool, these wool stockpiles were of very high quality wool – some of the best in the world. Thus as we can see, in the late 1930’s there was a large and solidly established textile industry in Australia manufacturing textiles in both wool and cotton, an experienced workforce and existing stockpiles of war materials available at reduced costs.

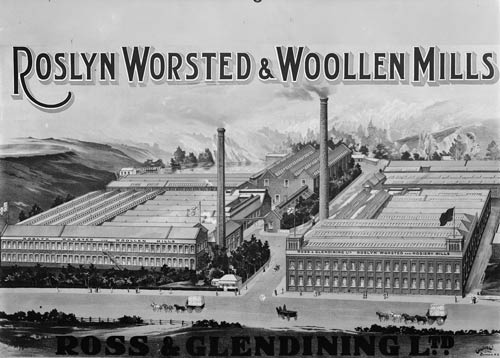

New Zealand was in a somewhat similar position and would also contribute a sizable quantity of uniforms for the Finnish military. New Zealand in the 1920s and 1930s also had a sizable textile industry and not only exported enormous quantities of raw wool (there were some 32,000,000 sheep in New Zealand in 1939 vis-à-vis 1,500,000 people) but also had a large number of textile and clothing factories, one of the largest of which was the Roslyn Mill outside of Dunedin, Otago. Employing 2,500 workers in its mills, clothing factories and warehouse, Roslyn Mills would complete and ship some 100,000 articles of winter clothing destined for Finland by mid-December 1939.

Roslyn Woollen Mills was only one of about a dozen New Zealand firms operating woolen mills on a similar scale who would also complete large quantities of winter uniforms for the Finnish military in record time. The Finnish orders for fabric for winter uniforms as well as for Army blankets kept the machines and clothing factories running 24 hours per day and stretched their capacity to the limit. Clothing manufactured from the various fabrics included special Shetland-blend underclothes and undershirts, heavy duty twill-weave woolen trousers, shirts, tunics, socks and heavy duty winter coats as well as woolen yarn for jerseys.

Besides Roslyn, other large New Zealand woolen mills included the Mosgiel Woollen Factory Ltd, Bruce Woollen Factory at Milton, the Oamaru Woollen Factory Co. and Lane Walker Rudkin’s Ashburton mill. In late 1939, war orders had not yet been placed and these mills had significant capacity available.

Cutting and sewing uniforms for the Finnish Army – a crowded workroom in the Roslyn Woollen Mills, Kaikorai Valley, Otago (New Zealand), December 1939.

Additionally, there was a large tannery industry in both Australia and New Zealand taking both sheep and cattle skins and either processing the hides into good quality leather or curing the hides in brine for both local use and for export. Tanning was in fact one of Australia’s oldest industries, with the earliest known tanners in the country operating in Sydney from 1803 – and in the early years of Australia, one of the few products other than wool that could be exported was hides, which could be salted and exported raw. The early tanneries were on a small scale and generally family-owned businesses with a number of workers, with some expanding in the early twentieth century as they processed hides for export or for use by footwear and clothing factories. It is also interesting to note that there was also a slowly growing trade in kangaroo hides, as it was realized that kangaroo hide made leather that was of higher strength, lighter weight and more durable than that made from steer hides with 10 times the tensile strength of cowhide and some 50% stronger than goatskin.

Workers pose outside the Keralgere Tannery at Morningside, Brisbane, Queensland ca. 1897 The men wear leather aprons and pose with a dog, tools and equipment. The ‘Rossiter Brothers’ sign is prominent on the workshop building, which has two-stories, a shingle roof and window awnings. The area is surrounded by bush and a horse and cart stands to one side

As with wool, significant stockpiles of raw hides and tanned leather existed, including (in Australia), significant quantities of kangaroo hide and kangaroo leather. Orders from Finland for various items of uniform and field kit (such as sheaths for Puukko knives, pistol holsters, belts and braces, straps for rucksacks, headwear, gloves and boots, as well as uniform clothing for tankers and aircrew would be manufactured in Australia and New Zealand from these stockpiles). This have a twofold effect on both countries – kickstarting the domestic textile industry into war production, so that when Government orders were finally placed the industry was geared up and ready, and also introducing some useful pieces of equipment that the Australian and New Zealand military would copy. We will look at these orders shortly.

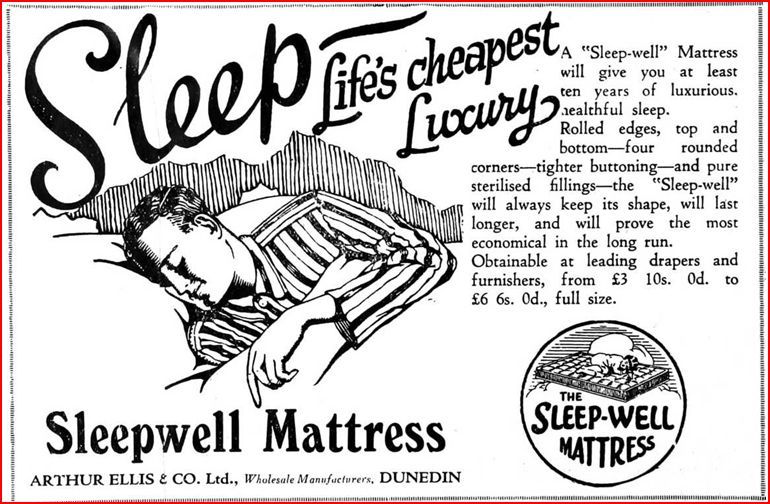

A.H. Ellis and Co & Sleeping Bags from New Zealand

Another iconic New Zealand company which would supply Finland with specialist winter equipment was A.H. Ellis and Co., a company which had been involved in the design and manufacture of specialist outdoor equipment since the 1920’s. They made the first down-filled sleeping bags in the Southern Hemisphere and from the 1930s, the company’s sleeping bags became essential equipment for all New Zealand outdoor enthusiasts. The company had started out in 1877 when Ephraim Ellis, a hand-loom weaver from Yorkshire and Nicholson, the pioneers of the business, imported a flock machine and started making flock for mattresses in a barn. Sixty odd years ago ideas on this subject were not so advanced as they are today and with a single machine driven by a water-wheel, they made flock from wool which was then sold to upholsterers and furnishing shops. Each Firm made up its own requirements in the way of bedding, which was looked upon as a mere sideline.

The firm was dissolved and renamed E. Ellis and Co. sometime in the 1880’s and some progress must have been made within the next twenty years in the notion of what constituted a satisfactory bed, for in 1896 the Firm began importing kapok from Java and teasing it for sale along with the flock. In 1901 the manufacture of wire mattresses was started but in 1906 this was dropped and the manufacture of bedding started. About the same time electric power was introduced, and E. Ellis and Company was one of the first Firms in Dunedin to take advantage of this more economical and flexible motive power. From that time the business steadily expanded, but the processes of mattress-making did not change materially. Bedding was still a primitive case filled with primitive material and, finished laboriously by hand.

In 1925 the Firm, now under the name of Arthur Ellis (Ephraim’s son) and Company Limited, modernized its bedding plant by importing machinery from America where rapid strides and revolutionary changes had been made in the mattress industry, and introduced the new style of inner spring mattress by importing the spring units and using wool felt batts for the filling instead of flock. Owing to the high cost of production, however, this type proved somewhat expensive and the older fillings were still also used. Another associated branch of the trade was started in 1926 when the factory was extended and equipped for the manufacture of down quilts. The whole process was undertaken from the importation of the raw feathers to the completion of the finished article, and “Faireydown” soon became a household word in New Zealand. In 1929 a furnishing warehouse was started in Dunedin, and this development proved so successful that branches were opened in Christchurch and Invercargill.

One or two members of the Ellis family were keen trampers (Kiwi slang for Hikers) in the rugged mountains of the Southern Alps of New Zealand. Out of this grew an interest in the design of sleeping bags and outdoor clothing suited to extreme conditions. Hiking even then was a popular pastime in New Zealand and with demand making itself known, the company soon began to manufacture sleeping bags for sale to hunters and hikers. Word spread beyond New Zealand and the company quickly gained a worldwide reputation for the sleeping bags and outdoor clothing it designed and produced for mountain climbing and for polar conditions – with Faireydown sleeping bags being used in expeditions to the Himalayas and to the Antarctic.

The Ellis family’s involvement in manufacturing outdoor products started in the 1920’s when Roland Ellis, combined his love of mountaineering with the manufacture of his company’s bedding products to develop and make the first down-filled sleeping bags in the Southern Hemisphere. From the 1930’s the company’s sleeping bags became essential equipment for all New Zealand outdoor enthusiasts. Post-WW2, the wide recognition of their excellence was endorsed internationally when Sir Edmund Hillary and Tensing used them during their first ascent of Mount Everest in 1953.

As a result of increase of demand for the Firm’s products it was felt necessary in 1937 to undertake considerable extension in both the bedding and quilt departments and advantage was taken of the opportunity to install the latest plant both for mattress-making and for treating feathers, as well as machinery for making spring units and other components, thus enabling the production of the inner spring mattress (hitherto regarded as a luxury line) at a lower cost and its adoption as the standard. The Firm now had a staff of 135 and the program of modernization was extended in 1938 by the erection of a building housing the new office-, and an engineering workshop capable of maintaining and developing the plant in the two and a half acres of buildings which the factory occupied for many decades.

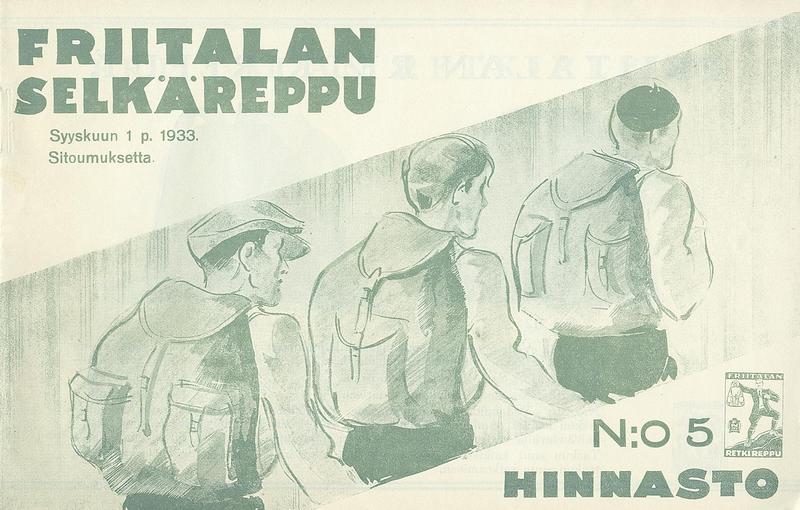

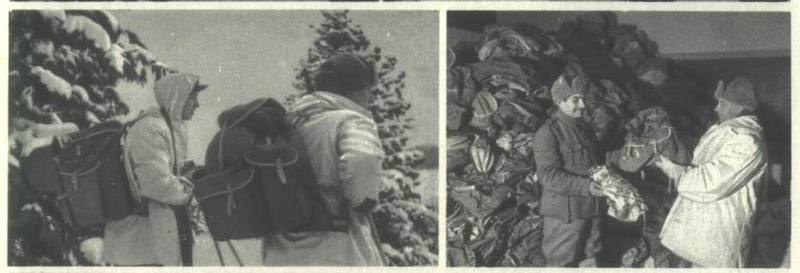

By 1939, A H Ellis & Co manufactured a small range of sleeping bags using either down or kapok as filling. These were rugged sleeping bags suitable for use in the alpine terrain of New Zealand and were designed to be durable, warm and lightweight (when compared to the weight of blankets that would be needed to provide similar warmth). At this time, it must be remembered that sleeping bags were very much a “luxury” item and were not in common use – and in fact much of the equipment that we now take for granted such as insulating pads to sleep on and load-bearing rucksacks were unheard of. In most of the Army’s of Europe a soldier’s rucksack and sleeping roll would look something like the picture below (although generally the blanket would be wrapped in a waterproofed groundsheet) – a very basic frameless rucksack with a bedroll and with additional equipment fastened on the outside. No real attention had been paid to the ergonomics of rucksack shape, loadbearing and design although you will see some rucksacks with a very basic waistband (which we will look at shortly).

While New Zealand and Australia would supply large quantities of easily manufactured woolen blankets for military use, another less significant contribution was the manufacture and delivery of some twelve hundred sleeping bags by A. H. Ellis & Co. in a rapid timeframe. At the time, as mentioned above, sleeping bags were primarily a civilian item rather than a military one – and would remain so until well after WW2 – in Finland, standard issue sleeping gear would remain a blanket and greatcoat until well after WW2. However, the Maavoimat special forces units that had evolved over the last years of the 1930’s and which were tasked with operating behind enemy lines had to a certain extent developed their own equipment – one piece of which was a cold-weather sleeping bag for use in arctic conditions.

The disadvantage of reindeer skins is of course that they are heavy and bulky and are not easily man-portable – here, an early primitive sleeping covering.

In this, the Maavoimat had drawn on the early experiences of Arctic and Antarctic exploration and the equipment used in particular by the Norwegian explorer, Amundsen – and before him, Fridtjof Nansen – as well as the ability to live in arctic conditions of Finland’s own Sami people.

Peoples living in the arctic such as the Sami have long used skins such as reindeer for insulating layers to sleep on, together with blankets and coverings made from animal skins and fur. As sleeping mats, these furs provided warmth and comfort, with the stiffness of reindeer fur meaning it does not compress under body weight, providing unparalleled insulation and comfort. The disadvantage of reindeer skins is of course that they are heavy and bulky and are not easily man-portable.

Sleeping bags as we now know them began to be developed in the last half of the nineteenth century. Perhaps the best known of these early developments was a prototype of an Alpine Sleeping Bag developed and tested in 1861 by Francis Fox Tuckett, an early Alpine Mountaineer. This prototype sleeping bag consisted of a blanket material with a rubber-coated fabric on the underside.

Francis Fox Tuckett FRGS (10 February 1834 – 20 June 1913) was an English mountaineer and one of the main figures of the Golden age of alpinism, making the ascent of 269 peaks and the crossing of 687 passes. In Scrambles amongst the Alps Edward Whymper called Tuckett “that mighty mountaineer, whose name is known throughout the length and breadth of the Alps”. Tuckett entered his father’s business as a leather factor and was also a gentleman farmer all of his life, taking two to three months off each year for alpine exploration (his first trip to the Alps was in 1842 in the company of his father). In 1882, his business, under the name of ‘Tuckett and Rake’, was at 18 & 20, Victoria Street, Bristol, and was described as ‘Leather, Valonia, and Raw Hide Factors’. He was vice-president of the Alpine Club from 1866 to 1868, and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. On 17 January 1896, at the age of 62, Tuckett married Alice Fox while he was in New Zealand on a climbing trip.

The next recorded development in the history of sleeping bags is the design, development and marketing of the “Euklisia Rug”, an all in one blanket, shawl and rug with a sewn in inflated pillow made in 1876 by the Welsh entrepreneur Pryce Jones, who also pioneered the mail order business. They were made from Brown Army Blankets originally made for the Russian Army. According to a copy of the Brown Patent ( http://a-day-in-the-life.powys.org.uk/eng/home/eo_euklisia.php ) in the Powys county archives, the wool sleeping bags were to be 2 yards and 11 inches long by 1 yard and 31 inches wide. These wool sleeping bags, which were the first to be mass produced and circulated, used fasteners to keep them closed. The success of this sleeping bag is supported by records which show that 60,000 Euklisia Rugs were sold to the Russian Army as well as being used in the Australian outback and missionary posts in Congo. It really didn’t look like a sleeping bag of today as it’s more of a folded rug but with a couple of fasteners it would certainly be more recognisable as a sleeping bag. Despite these records none of the aforementioned sleeping bags survive today, however the rug has been recreated using the original patent by an antique cloth specialist and donated to Newtown Textile Museum where it is now on display.

In 1889, the first commercially produced sleeping “bag” (as opposed to a blanket) was designed and developed by Fridtjof Nansen and the company Ajungilak of Norway, for Nansen’s first expedition to the North Pole. The bag was made from reindeer fur and kapok fiber (Kapok fiber comes from the Kapok tree and is light, buoyant and resistant to water. Kapok fiber was often used in place of down as it retained its insulating value even when wet, until it was superseded by synthetic fillings in the 1980’s). Ajungilak of Norway was founded in 1855 in Oslo, Norway by Jacob Michael Breien, originally specialising in blankets, pillows and clothing filling and going on to be among the first to develop synthetic sleeping bags. In 1920 they made their first down sleeping bags and in 1932 they began to focus on the sleeping bag business. Also in 1932, Martin Mehren and Arne Hoygaard crossed Greenland using Ajungilak sleeping bags. Today Ajungilak is part of the Mammut Sports Group AG – and reindeer fur and kapok fiber are not currently used.

In Canada, similar development was running in parallel. The Canadian firm of Woods Canada, established in 1885 in the Ottawa valley by James W Woods to supply Canadians with canvas products, tents, sleeping bags and clothing designed for Canada’s harshest regions, entered the market for sleeping bags in 1895, producing bags under the “Woods” label. Between 1895 and 1900, Woods Canada provided equipment and clothing for countless Canadian pioneers and prospectors, with sales soaring with the discovery of gold at Bonanza Creek touching off the Klondike Gold Rush. In 1905, Woods products sailed with Amundsen on the tiny sloop Gjöa through the Northwest Passage and between 1906 and 1915, Woods would work closely with Amundsen to prepare equipment and clothing for Amundsen’s expedition to the South Pole and his subsequent First Canadian Arctic Expedition (1913 – 1915). Woods would design the Arctic parka, combining outer shells of their patented Canatite® canvas with down insulation and traditional fur hoods – and Amundsen’s expedition would take Woods sleeping bags to the South Pole.

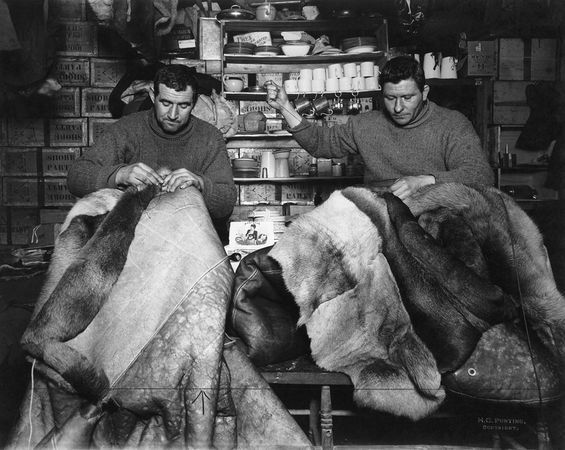

By contrast with Amundsen’s scientifically designed, developed and tested equipment, the British Antarctic Expedition of Robert Scott would make use of the now primitive reindeer fur sleeping bags. These had seem some improvements in design – they were tapered at the feet for example, similarly to today’s Mummy Bags, but they also froze solid in the extreme cold, meaning the user had to more or less thaw there way into them, and the reindeer fur trapped condensation inside, meaning continual ice buildup. The bags used by Amundsen would prove superior. (Incidentally, the reindeer fur sleeping bag used by Captain Lawrence Oates on Scott’s expedition is on display today at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge (UK).

Through the 1920’s and 1930’s, the old reindeer fur bags disappeared, to be replaced in mountaineering and expedition use by either down-filled or kapok filled bags – or, for less extreme use, wool-filled bags. The type of fill used largely depended on climatic conditions – down was more suitable for extreme cold at high altitude where it could be expected to be drier, while kapok was preferred if there was a risk of the bags becoming saturated with water. Down certainly weighs less than kapok and retained heat better, but it cost more and if it did get wet, it provided even less insulation than no sleeping bag at all – something that could prove fatal in cold conditions. To a certain extent this could be overcome by the use of sleeping bag covers made of a waterproofed material, generally a light canvas with a rubberized-canvas base – but again, this added more weight. Wool repels water nicely and also resists compression, but it weighs much more than any of the other alternatives and when it did get soaked, weighed even more. Cotton suffers from high water retention and significant weight, but its low cost makes it an attractive option for uses where these drawbacks are of little consequence.

Frank Wild & Watson in reindeer fur sleeping bags and tent on sledge journey – Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911-14

As mentioned, in the late 1930’s, special forces units within the Maavoimat began experimental use of civilian-type sleeping bags such as that illustrated below. For winter use, the Maavoimat began trials in 1938 with a small number of down-filled Ajungilak sleeping bags manufactured in Norway. There were around one hundred of these bags in Finland at the start of the Winter War and the reports from the winter warfare experiments over December 1938 to March 1939 had rated them highly. In the trials, a few improvements had also been made, included a collar round the neck to retain body heat within the bag and a “hood” to enclosed the head.

Down on the underside had also been reduced as when compressed by body weight, it provided very little insulating value – instead, a lightweight rubberized-paper waterproof insulating pad that rolled easily was being trialed. The real benefit for the special forces units whose mission was to operate behind enemy lines for prolonged periods of time was the reduction in weight and improved comfort and warmth offered by the down bags – warmth in winter being a critical factor given that it was often impossible for small units behind the enemy lines to use stoves to keep warm. The down bags therefore offered real potential to the special forces units in extending the length of time at which they maintained themselves at peak condition.

A lightweight Kapok-filled civilian sleeping bag manufactured and sold in Finland in the late 1930’s for summer use

he Maavoimat would continue to issue blankets to soldiers for general use. However, the modified Ajungilak sleeping bags that had been trialed proved to be useful enough that the Purchasing Teams were asked to purchase anything similar if this proved possible. In the event, two sources of supply were identified and orders placed. A H Ellis & Co in New Zealand would go on to manufacture twelve hundred sleeping bags and covers in the short period of time available, incorporating the new design features requested by the Maavoimat.

Some six hundred down bags would also be purchased from Ajungilak in Norway and a further five hundred from Woods in Canada, together with a smaller number donated by well-wishers and a couple of hundred kapok and down bags donated by owners in Finland and a similar number from Sweden. The end result was that around 1,800 down sleeping bags were available for issue to special forces units operating behind the Soviet lines. It was not enough – but it helped, and those lucky enough to be issued a down bag certainly benefited in the months of winter warfare that were waged.

Photo, left: A. H. Ellis & Co down filled “Nordenskiöld” bag with water-resistant cover. This is the early issue Maavoimat winter-weight sleeping bag for special forces use, manufactured in late 1939 and delivered to Finland in early 1940. Some 1,200 were manufactured in New Zealand for use by the Maavoimat. No further bags were made after the initial run as A. H. Ellis & Co used up their down stockpiles and could not source further supplies until after the war.

However, A. H. Ellis & Co would go on to manufacture sleeping bags of a similar design but with a woollen filling rather than down. These were mummy shaped and weighed less than the blanket that was standard issue. However, while an early order from Finland for 50,000 bags was completed and delivered, the Winter War ended before further orders were placed. Finland would go on to manufacture similar bags domestically for the Maavoimat over 1941 to 1943, equipping a sizable minority of the military with these bags. However, the majority of the soldiers who fought over the period 1944-1945 in the war against Germany would continue to use the old-style blanket and greatcoat combination and it would not be until many years later that sleeping bags would see common use.

That said however, the small number of down bags that were supplied from New Zealand would also arrive too late to be of any real use in the winter fighting period of the Winter War. However, they were certainly appreciated by the special forces units in the fighting against Germany, by which time they were standard issue as it had proved possible to source more such down-filled sleeping bags from Canada.

Returning to Rucksacks

Soldiers must carry what they need to fight with. This is an axiom that is true to all armies, even those that are heavily mechanized as at some stage, soldiers will need to dismount and fight with what they are carrying. This was even more so in WW2 when no armies were mechanized (although some had mechanized units) – and for the Maavoimat, whose frontline combat strength consisted almost entirely of infantry, this axiom was as true as for any. Even more so when the nature of Finland’s terrain outside of the Karelian Isthmus called for a mobile defensive war to be fought on foot in forest, lake and swamp terrain along a thousand miles or border. In this sort of warfare, the load carrying capabilities of the individual soldier are critical.

In managing load, the most important point to keep in mind is that an infantry rifleman should carry only the items necessary to complete the immediate mission at hand. The more weight the soldier has to carry, the more rapidly he becomes exhausted. And while fatigue is the infantry soldiers life in the field, fatigue can reduce an effective unit to a leaderless gaggle even in the most benevolent terrain. With rough terrain and bad weather, the effects of fatigue multiply exponentially. The more hills you have to climb and the worse the weather (and in winter in Finland, think VERY cold – and add in a snowstorm or blizzard together with deep snow), the faster you are going to tire. Physical training reduces that rate of fatigue, but does not eliminate it. On the other hand, carrying too much weight can quickly accelerate exhaustion – and carrying too much weight in an uncomfortable position or in a position that throws off natural balance and the soldiers life becomes even harder than it already is.

Day Eight of Basic Training for Maavoimat conscripts in the first training intake of 1938. Fatigue shows on the faces of the young infantrymen. Typical of central Finland weather in January, the days were cold and the nights were colder still, often marked by heavy snow. The sergeant-instructor worked hard to keep the soldiers motivated and moving under their combat loads. No one wanted to be cold or wet, so the rucks were especially heavy. With combat loads of ammunition, grenades, iron-rations, bedrolls, cold weather clothing and their individual share of rhymaa equipment each soldier carried around 80 pounds of gear. After seven days of constant day and night operational training, the effects of carrying that weight were showing. Even the fittest of the platoon were hollow-eyed with fatigue. Their reactions were slow and their minds fuzzy. They rucked up and moved on toward their next mission, an attack on a suspected strong point five kilometers away. Less than 500 meters into the movement, the tired point man missed seeing movement ahead as he cleared the edge of a small grove. The opposing force ambushed the platoon with complete surprise. No one survived.

An even more direct effect of overloading soldiers beyond the effect of fatigue on combat capability is the physical effect of fatigue and stress on the soldiers themselves. Though the common sense rule of “the higher the load, the slower the movement” applies, it is often ignored. The effects can be more long term with an increased risk of back injury. Army doctors even have a term for it – “Infantry back.” Symptoms are lower back pain, fatigued spinal muscles, back strains, or, in extreme cases, scoliosis (curvature of the spine). With the Maavoimat, units were trained to operate independently with mobility and flexibility emphasized. In the 1920’s and early 1930’s, this often meant even heavier loads than were the “standard” were carried to allow for problems with the logistical tail keeping up. No-one wanted to be without ammunition at a critical point in a mission for example. And during winter the weight of the load carried increased. This was due to carrying extra clothing and cold weather gear. In summer however, much of the weight reduction from not carrying winter equipment is offset by the need to carry more water.

The Maavoimat, as with other armies, carefully studied infantry combat (“fighting”) loads and load-bearing kit to carry this. Load-bearing equipment, designed as a combat harness and intended to carry the “fighting load”, is generally made up of a belt to which equipment may be attached or hung, and belt suspenders which perform a similar function as well as helping to support the weight of the equipment belt when loaded. The “fighting” load generally includes ammunition (both in magazines and loose in additional pouches), grenades, a small pouch with first aid materials, fighting knife in sheath, a bayonet and a water bottle. Additional small pouches could also be attached to carry a compass or watch. These are all essential items for the combat infantryman to fight with and are essential to his effectiveness in combat. Everything else – rucksacks, bedrolls, extra water – are by definition “existence load” added on top of the combat load. Those “existence” items may be necessary for long-term survival but they may also make a soldier comfortably dead if he is too tired to function as a result of carrying them.

In addition to the individual fighting load, the soldier’s load also consists of “existence” items which are required to sustain or protect the infantry rifleman, which may be necessary for the infantry rifleman’s increased personal and environmental protection, and which the infantry rifleman normally would not carry when fighting. When possible, the individual existence load items are transported by means other than man-carry. Otherwise both the “fighting” and “existence” loads are carried by the infantry rifleman. Individual existence load items are usually carried in the field pack, or rucksack.

Normal winter equipment issued to a Maavoimat infantryman, as per the Sk.Y publication (Helsinki 1933), “Manual for Soldiers Field Gear Maintenance” and confirmed Jan 1, 1934 for Enlisted Men.

Clothing generally worn: Tunic m27, Pants m27, Underwear, Sweater, Field cap m27, Overcoat m27, Snow coat (winter whites), Gloves, Leather gloves, Leather belt, Belt buckle, Suspenders or Y-Straps, Boots, Socks or cloths used as socks in the Finnish Army, Helmet, Skis & ski poles, Dog tags, Cockade, Bandolier, Snow goggles or mask;

Weapons and combat load: Rifle, Rifle sling with buckle, Rifle muzzle cover, Bayonet, Bayonet frog, Bayonet metal hooks, Ammo pouch (s), 1 ration rifle ammo (number of pieces of ammo not mentioned but standardized in 1938 as 8×20 round magazines for the new Lahti-Saloranta 7.62 SLRs being issued), Personal medical kit, Compass (group or officer gear), Binoculars (group or officer gear), Grenade(s), Water bottle (canteen), Puukko Knife and sheath;

Existence Load: Reppu (Rucksack), Breadbag, Leather straps for pack, Groundsheet, Blanket, SY cleaning kit for Rifle, Rifle cleaner fluid, Oil bottle marked SY, Gas mask, Shovel and belt holder (for use in attaching to rucksack), Messkit, Mess kit leather straps, Cutlery, Cup, Shaving kit or personal kit, 1×8 foot length of rope, iron rations, Share of rhymaa equipment (share of shelter, portable stove, machinegun ammunition, additional loose rifle ammunition, mine(s), additional grenades).

Note that no additional clothing was carried, only what was worn. In extreme cold however, more than one blanket might be carried and additional sweaters and a scarf might be worn. Over the period from 1935 on, equipment improvements and the introduction of new weapons led to a steady increase in the amount of weight an individual infantryman was expected to carry. From 1938 on, pistols began to be issued for individual riflemen as a backup weapon (this was a matter of individual choice) and infantry ryhmaa began to be issued with new anti-personnel mines which had to be carried. The issuing of the new Lohikäärme Vuota body armour starting in late 1939 added an additional 8-10 lbs of weight to the individual soldiers load.

The introduction of new weapons with high rates of fire such as the rhymaa (section) light machinegun, the Sampo, and the Suomi submachinegun all required the infantry rhymaa to carry a considerable amount of additional ammunition to feed these weapons. And while the Sampo was a tremendously effective light machinegun, it could use a lot of ammunition in a short timeframe. There was also the Rumpali (the new shoulder-fired mini-mortar – more commonly now referred to as a grenade launcher) whose rounds were not light, particularly when each infantryman carried an additional dozen or more rounds – and when you were going into battle, you certainly wanted as much ammunition available as possible. There were also the new man-portable Nokia radios which the Company (and as more became available, the Platoon) needed to carry.

Over the same period, serious efforts were made to improve the Maavoimat’s logistical supply capabilities. One of the biggest determining factors in infantryman loading is a soldiers confidence in the logistical system. The Pohjan Pohjat volunteer unit that had fought in the Spanish Civil War had identified this as a consistent issue – that soldiers at the platoon level had lacked confidence in the logistical system. This had lead to the soldiers overloading themselves with items they considered essential when going into combat – generally ammunition, water and food. Analysis of the experiences of Pohjan Pohjat made a point of emphasizing that this had to be addressed – when soldiers request ammunition, water and food, those requests must be command priorities. Effective staff planning should forecast when those demands would arise and emergency resupply, in a reactive mode, should be the exception in all phases of operations. In the defense for example, soldiers should not have to wait to be supplied with barbed wire, anti-personnel and anti-tank mines and additional stockpiles of ammunition. They should get these critical items as soon as they begin to move into a defensive posture.

To this end, numerous improvements in the Maavoimat logistics organization took place over the period between 1935 and the start of the Winter War – to provide the support needed, logistical operators needed both the physical assets (including security) and the training opportunities necessary to ensure they could perform their mission during operations. This topic will be covered in subsequent posts as we look at the organization and equipment of the Maavoimat in later posts. For now, suffice it to say that the emphasis was twofold – one emphasis was on ensuring that soldiers knew that they could rely on regular resupply (and ensuring this happened) while the second was on managing the individual load carried by each rifleman.

Tailoring the Load

The Infantry Manual advised that “the load an infantryman carries should not include any other item that can be carried in any other way. Determining the soldier’s load is a critical leadership task. The soldier’s load is always mission-dependent and must be closely monitored. Soldiers cannot afford to carry unnecessary equipment into the battle. Every contingency cannot be covered. The primary consideration is not how much a soldier can carry, but how much he can carry without impaired combat effectiveness.” The 1939 manual goes on to state that the soldier’s combat load should not exceed 75 pounds. That limit combines the fighting load – weapon, magazines with ammo, grenades and water canteen weighing in total about 35 pounds together with 10 pounds of body armour – and the rucksack and selected items at 30 pounds. Remaining equipment and materials needed for sustained combat operations form the “sustainment load” to be brought forward by company and battalion when needed.

Officers and NCO’s were advised to ensure the men carried only what was required to carry out the assigned task, allowing only the minimum necessary of “comfort” items. With the type of task, terrain, and environmental conditions influencing the clothing and individual equipment requirements, the unit commander was instructed to set out to the infantrymen the essential items that were to be carried. Leaders were trained to conduct load inspections to ensure load instructions were adhered to.

There were four standard load configurations specified in the manual as a guide:

Fighting load – Only what is worn = 46.9 pounds

Fighting light – Worn plus a small assault “breadbag” = 59 pounds

Approach march – Worn plus the rucksack = 74.9 pounds

Everything – Worn plus the rucksack, assault breadbag, additional ammunition and rhymaa equipment = 95 pounds

During summer exercises in 1938, the initial soldier’s load was sampled. Some units entered the exercise area at fighting light (59 pounds), some at the approach march (74.9 pounds). Of the 13 units samples, only one unit entered the fight at fighting load (46.9 pounds). Typically, units in the summer exercise entered the fight at fighting light (59 pounds) or the approach load (74.9 pounds), and in the winter exercises at the end of 1938 entered the fight either at approach load (74.9 pounds) or everything (95 pounds). Putting this into task, enemy, troops, terrain, and time available (TETT-T) perspective, during the summer exercises units came into the fight between 13 and 35 pounds heavier than they should have been. The winter exercise units came into the fight between 15 and 35 pounds too heavy. The net effect was that units in both summer and winter overloaded themselves to the extent that for some, their fighting ability was impaired.

As a result, Officers and NCO’s were advised to consider the risk versus gain aspects of combat loading soldiers. They were advised that as long as soldiers had their mission-essential equipment, they might be uncomfortable at times, but they would be able to sustain their combat effectiveness. Conversely, if soldiers were overloaded and they collapsed from the weight of non-essential items, they might not even reach the objective. By overloading their men with comfort-related items, leaders in effect expended them before they had the opportunity to fight. In considering all of this of course, load-carrying kit and rucksacks were essential.

In late 1939, as the Maavoimat mobilized, it was not only uniforms that they were short of. The Maavoimat certainly had rucksacks, but in 1937 they had begun to reassess rucksack design as a result of the increased load that was being carried and had finally settled on an improved rucksack design – but this had only just started being produced. As a result, there was a substantial shortage or combat rucksacks. Rear-area troops had their rucksacks returned for reissue to combat troops and instead, were issued with whatever was available.

Whatever civilian rucksacks were available were requisitioned and issued to rear-area troops. Swedes would also donate many civilian rucksacks.

The Norwegians would donate 37,000 military rucksacks to Finland. These were suitable for use by combat soldiers and made up a good part of the shortfall for the frontline units.

As you can see, two carrying straps, no reinforcing where the tops of the straps are attached to the canvas. With a heavy load, this type of rucksack was uncomfortable and also, with no waistband,, insecure when moving strenuously.

Same backpack, view of carrying straps, again no waistband. Note there is no frame for support – this type of frameless rucksack is essentially a carrying sack with all the weight supported by the shoulders. Colloquially known as a “kidney crusher” as that’s where it bounced when you walked or ran while carrying it. Most unsuitable for the carrying of heavy loads, and worse still when anything hard with straight edges was inside it and close to your back. Nevertheless, they were available and remained in use throughout the Winter War although by 1944 they had been largely retired.

The so called “satulareppu” (saddle rucksack) was the “new” design intended to replace existing rucksacks. With a larger capacity, ergonomically improved design and more comfortable to wear, it was an excellent design for the time. Manufactured domestically, large quantities of canvas and leather donated to Finland by the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation would make the ongoing manufacture in large quantities of this model rucksack possible.

Note the improved load-bearing and support design – waistband, criss-cross straps on the back helping to support the load, metal frame which assisted in keeping the load off the back, leather straps on the sides and top for fastening external items to the rucksack easily. This was a vast improvement over the earlier models. In late 1939, manufacturing of this rucksack had been underway for only just over a year and numbers in stock were limited. Large numbers (well over two hundred thousand) would be manufactured and issued over the course of the Winter War and by 1943, this rucksack would be the standard issue to all Maavoimat soldiers – largely made possible by the large shipments of canvas and leather dispatched from Australia.

Over the course of the Winter War, the Maavoimat would also acquire large numbers of Red Army rucksacks from their previous owners. As with much other captured and recovered Red Army equipment, these would be reissued within the Maavoimat and many would see service through to the end of WW2.

Finnish Uniforms from Australia and New Zealand

Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus were well aware of Australia’s (and to a lesser extent New Zealand’s) reputation as an exporter of wool and hide. Prior to WW2 Finnish cargo ships had been regular visitors in Australian ports, loading shipments of grain, wool and hides for export. As has been noted in an earlier post, some of the last sailing ships in the world transporting commercial cargos were the Finnish-owned sailing ships on the grain route, the “Cape Horners”, loading grain in Australia and then sailing across the Southern Ocean, rounding Cape Horn and thence to Europe. (For a fascinating insight into life on these ships, read Eric Newby’s “The Last Grain Race” and his “Learning the Ropes: An Apprentice on the Last of the Windjammers” which has an amazing collection of photos showing what life was like on these sailing ships). With a Finnish consulate in Sydney, Finland was well-briefed on the Australian economy and Australian industries and the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus team (and the Purchasing Team that accompanied them) were well-prepared.

Finland had generally imported what wool that was not produced locally from Argentina and from the British Commonwealth countries of Australia and New Zealand – and with a fairly large domestic textile industry, business ties with Australian exporters existed. War planning had identified both Australia and New Zealand (and Argentina) as a potential source of supply for wool, canvas leather for the manufacture of military uniforms and military equipment and this was in fact one of the key areas that the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus team in Sydney was intended to focus on when negotiating for assistance. And there WAS a major need. As has been mentioned a number of times, Finland had spent a considerable amount of the state budget on defence, together with loans and fund raising through Defence Bonds. However, the main focus of spending had been on weapons, munitions and equipment – NOT on uniforms and uniform “accessories” such as belts, webbing, suspenders, sheaths for knives, winter hats, gloves, etc. “You can’t shoot someone with a uniform” was the general thought through the last years of the 1930’s and the emphasis had always as a result been on weapons and munitions – and despite the all-party support for increased defence spending, there was in Finland a continuing strong under-current of resistance to any expenditure thought of as “unnecessary”. And so, while there were just enough uniforms for the conscripts undergoing training, and for the Suojeluskuntas and Lotta Svard members who had paid for them themselves, there were to few uniforms available in military storage depots and warehouses for the soldiers mobilized from the general reserves.

As the Finnish military had quietly mobilized over the summer and autumn of 1939, this had become more than obvious, with mobilized reservists referring rather sarcastically to their “Model Cajander” uniforms. This was a pointed reference to the Finnish Politician and Prime Minister Aimo Cajander, who even at this late stage and despite the intelligence reports and aerial reconnaissance photographs taken from Ilmavoimat Wihuri photo-recon aircraft flying at high altitude over the USSR, did not believe that the Soviet Union would actually attack Finland – he had consistently been strongly opposed to increased defence spending and had at one stage stated that “I would rather see the money that we waste on defence spending go to build schools for our children rather than pay for uniforms for soldiers to molder in warehouses.”

This statement had been made at the height of the debates over increased defence spending following the Munich Crisis and it had been with bad grace that Cajander had allowed himself to be overruled, with the defence budget drastically increased while other “social” spending, which he regarded as far more useful, was cut. Cajander had however scored a minor victory – he had his way in ensuring that no defence funds were “wasted” on uniforms – “we’re paying for the defence of Finland, not for the military to display themselves like peacocks” as he put it – with the end result being that Cajander’s name is now best remembered for the “Model Cajander” uniform which most Finnish reservists wore at the start of the Winter War: Soldiers were given a utility belt, an emblem to be attached to their hat — to comply with the Hague Conventions — and otherwise, they had to use their own clothes. Fortunately, the Finnish Army had more than enough weapons, ammunition and increasingly, the new “Lohikäärme Vuota” body-armour – but of uniforms, nowhere near enough.